Capitol Architectural Report, Block 8 Building 11Architectural Report The Capitol Block 8 -- Building 11 Part I - III

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0036

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

THE CAPITOL

Block 8--Building 11

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

THE CAPITOL

Block 8--Building 11

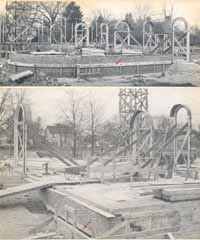

Reconstructed under the direction of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, architects for the Williamsburg Holding Corporation between October, 1931 and January, 1934. For a detailed listing of the organizations and persons who participated in the work on the Capitol, see the Appendix of the report.

Part 1 of the report introduces the subject of the Capitol by reviewing possible English antecedents of this exceptional structure and by pointing to subsequent buildings in Virginia and the neighboring colonies the design of which, in one respect or another, was influenced by it. It outlines the history of the first and second buildings, down to 1928 when the site was presented to Colonial Williamsburg, Inc. by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. The report then reviews certain puzzling questions concerning the original building which arose when the documentary and archaeological data were studied, in preparation for the reconstruction of the structure. The body of the report lists, detail for detail, the precedent followed in the design of the various features of the building, the exterior being treated in Part 1 and the interior in Parts 2 and 3.

The chief sources consulted in the writing of this report were the following:

- Capitol Notes, a compilation of all available seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth century references to the Capitol, issued by the Department of Research and REcord in March 1932.

- Capitol Notes, a discussion of factors which influenced the design of the reconstructed building, by Andrew H. Hepburn, revised in October, 1946.

- Architectural Record, which gives the precedent followed by the architects in the design of many features of the building. This was written by Thomas T. Waterman in February, 1932.

- The correspondence files relating to the Capitol of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, Colonial Williamsburg and of the builders, Todd and Brown, Inc.

- The working drawings and specifications followed in the reconstruction of the building and the progress photograph file on the Capitol.

This report was written by Howard Dearstyne for the Architects' Office of Colonial Williamsburg. Part 1 was completed in draft form in October, 1954. This was reviewed by Singleton P. Moorehead and Orin M. Bullock, corrected and typed in final form in November-December, 1954. It was bound December 8.

[Eagle emblem]

[Eagle emblem]

Ever will the thought of this reconstructed Capitol move us profoundly, for here as Councilor or Burgess sat nearly every great Virginian of the 18th century; here were spoken words that will never die; here plans were laid and actions taken of untold moment in the building of this nation. What a temptation to sit in silence and let the past speak to us of those great patriots whose voices once resounded in these halls and whose far-seeing wisdom, high courage and unselfish devotion to the common good will ever be an inspiration to noble living. To their memory the rebirth of this building is forever dedicated. Well may we say to ourselves in the words which the Captain of the Lord's host spoke unto Joshua:

"Loose thy shoe from off thy foot, for the place whereon thou standest is holy."

From address or John D. Rockefeller, Jr., delivered on February 24, 1934 at a special session of the General Assembly of Virginia held in the House of Burgesses Chamber to signalize the completion of the reconstruction or the Capitol.

The eagle on the previous page was taken from the title page of The Works of Colonel John Trumball / Artist of the American Revolution by Theodore Sizer, New Haven, 1950. A note in the book explains that the eagle appeared originally at the top of a music sheet entitled Hail! Columbia, Death or Liberty, A. Favorite New Federal Song, which was published in Boston in 1798.

| DEFINITIONS OF CERTAIN TERMS USED IN THIS REPORT | v |

| ENGLISH PREDECESSORS AND VIRGINIAN DISCIPLES | 1-22 |

| PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED IN RECONSTRUCTION OF CAPITOL | 23-63 |

| ARCHITECTURAL DETAILS OF THE CAPITOL AND THE PRECEDENT ON WHICH THEY WERE BASED | 65-147 |

| METHOD OF TREATMENT OF FEATURES OF A FACADE | 67, 68 |

| NOTES CONCERNING CONSTRUCTION OF PRESENT BUILDING | 68-73 |

| SOUTH ELEVATION | 76-114 |

| WEST ELEVATION | 116-129 |

| NORTH ELEVATION | 130-134 |

| EAST ELEVATION | 136-138 |

| COURT ELEVATIONS | 140-147 |

| INDEX | 148 |

DEFINITIONS OF CERTAIN TERMS USED IN THIS REPORT

Several words used frequently in the report are given specific or specialized meanings and this glossary is included here to obviate the danger of their being misinterpreted.

The word existing is used to designate features of the building which were in existence prior to its reconstruction by Colonial Williamsburg.

The phrase not in existence means "not in existence at the time of reconstruction."

The word modern is used as a synonym of recent and is intended to designate any existing eighteenth-century building which is a replacement of what was there originally and which is of so late a date that it could not properly be retained in an authentic restoration or reconstruction of the building, or be used as precedent in the restoration or reconstruction of another building.

The word old is used to indicate anything on or in a building that cannot be defined with certainty as being original but which is believed, nevertheless, to stem from the eighteenth century.

The term restoration is applied to the reconditioning of an existing building in which the walls, roof and many of the architectural details are original but in the case of which decayed parts have been replaced with new ones patterned after the old and missing elements have been supplied in the form either of old parts from other eighteenth-century buildings or of new ones of authentic eighteenth-century design.

The term reconstruction is applied to a building which has been wholly rebuilt in the position of the old foundations on the basis of archaeological and documentary evidence as to the nature of the original structure.

Length signifies the greatest dimension of a building or building part measured from end to end.

Width and breadth are used in this report to mean the dimension of a building or building part measured at right angles to the length.

Depth, in addition to meaning extent or distance downward, is also used in the sense of extent or distance inward or backward, so that we may, on occasion, speak of "the depth," of a lot, a building or of a room,

THE CAPITOL

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

PART 1

THE CAPITOL

ENGLISH PREDECESSORS AND VIRGINIAN DISCIPLES

JAMESTOWN STATEHOUSE BURNS AND A CAPITOL BUILDING IS PROJECTED FOR MIDDLE PLANTATION

When the statehouse in Jamestown was burned in 1698 the government of the Virginia colony was moved to middle Plantation which was thereafter called Williamsburg. A new statehouse, to be known as the Capitol, was ordered to be built there and until it was completed Governor Francis Nicholson, the councilmen and the burgesses carried on the affairs of government in the Wren Building of the Collage of William and Mary, a structure which had been built some years before.

LEGISLATIVE ACTS GIVE SPECIFICATIONS FOR ERECTION OF CAPITOL; THESE BASED ON EXISTING PLAN; BLAND SHOWS BUILDING ON LAYOUT FOR NEW CITY

Two acts passed by the legislature (June, 1699 and August, 1701)* gave explicit directions for the building of the city of Williamsburg and the Capitol. The directions for building the Capitol are so exact and so complete that we are forced to the conclusion that they are the verbal interpretation of previously-existent, exactly-executed drawings made for the structure. This theory becomes for us a matter of fact when we read the following in the record of the proceedings of the House of Burgesses for May 25, 1699:**

Upon further Consideration of the State house to be built being referred to this day and againe debated, The House agreed as followeth

That the House be built according to the forme and Dimentions of the Plott or Draught laid before the House.

It was doubtless this "Plott or Draught" upon which Theodorick 2 Bland draw when, having been commissioned in 1699 to survey the site for the new town, he made a layout for the latter and included therein a plan of the projected Capitol {see plate, p. 3). This plan gives the form of the building essentially as it was later built, except that both of ends of each wing are squared off whereas the Act of 1699 specifies that one end of each is to be made semi-circular. Since his plan for the new city and its two water approaches is of the utmost simplicity and includes buildings (Bruton Church and the Wren Building are also shown), without doubt, only to give their locations. Bland did not hesitate to schematize his indication of the Capitol and to square off all four ends.

UNCERTAINTY AS TO WHETHER CAPITOL WAS DESIGNED IN ENGLAND; POSSIBILITY THAT WREN WAS THE ARCHITECT

We have no way of demonstrating the validity of the supposition that the Capitol was erected from plans drawn in England. It seems reasonable to assume this since we know it to have been the case with the Wren Building of the College of William and Mary, the construction of which was started in 1694, a very few years before the beginning of the Capitol (1699). Of the Wren Building, Hugh Jones was for some years a professor of mathematics at the College and chaplain to the General Assembly, says, in his The Present State of Virginia, London, 1724, that it was "first modelled by Sir Christopher Wren, adapted to the nature of the country by the Gentlemen there…" Jones, in the same book, describes the Capitol and, although he makes no statement as to the designer of this, he says of the House of Burgesses that it "is not unlike the House of Commons." We are uncertain whether he was comparing the architecture of the two legislative bodies or likening the one to the other on the basis of function and procedure. This subject is

3

4

treated at some length on p. 56, in the caption to a picture of the House of Commons. The question therein raised as to whether Sir Christopher Wren, as surveyor general to the crown, m.y have had a hand in the design of the Capitol cannot, in the present state of our knowledge as to the origins of the building, be answered satisfactorily. Since it has a possible bearing on the matter, it seems appropriate to quote here a statement made by Nathaniel Lloyd on p. 115 of his A History of the English House, London, 1931. Lloyd speaks of "Wren's practice of furnishing designs, with or without detail drawings, for provincial buildings and leaving the execution of the work to others…." There is considerable probability that this is what he did in the case of the

Wren Building and he may well have done the same thing for the Capitol.

4

treated at some length on p. 56, in the caption to a picture of the House of Commons. The question therein raised as to whether Sir Christopher Wren, as surveyor general to the crown, m.y have had a hand in the design of the Capitol cannot, in the present state of our knowledge as to the origins of the building, be answered satisfactorily. Since it has a possible bearing on the matter, it seems appropriate to quote here a statement made by Nathaniel Lloyd on p. 115 of his A History of the English House, London, 1931. Lloyd speaks of "Wren's practice of furnishing designs, with or without detail drawings, for provincial buildings and leaving the execution of the work to others…." There is considerable probability that this is what he did in the case of the

Wren Building and he may well have done the same thing for the Capitol.

LIKELIHOOD THAT CAPITOL DEVELOPED OUT OF A BUILDING TYPE EXISTING IN ENGLAND

Even if one saw fit to reject the thesis that the Capitol was designed in England, he would still have to look to the mother country for the forerunners of the building form. It is seldom that a new building type springs full blown from the mind of some gifted creator; such innovations represent, rather, advances upon or alterations of older forms. Since it was customary for the Virginia colonists at this period to turn to England for architectural guidance, we may expect to discover among buildings which existed there at the time structures with characteristics which relate them to the Capitol. We should find, therefore, buildings having H plans, others with arcades and still others in the designs of which cylindrical or half-cylindrical forms have been incorporated, to mention only the most striking features of the first Capitol.

U, H, AND "HOLLOW SQUARE" PLANS POPULAR IN ENGLAND; TWO HOUSE WITH H PLANS

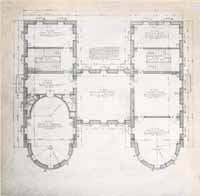

It should be remarked here that plan types in vogue in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries included, among others, 5 the simple rectangle; the U-shaped plan, obtained by adding, at the ends of the rectangle, two wings at right angles; the "hollow square" plan (projected for the Wren Building but never completed), which results when two U's are joined at the ends of the wings, and the H plan which is formed, theoretically, when two U's are placed "back to back." We have no difficulty tracing the English origin of the H plan of the Capitol since, according to Nathaniel Lloyd; the Elizabethan house generally took that form (p. 212, A History of the English House). Elizabeth reigned from 1558 to 1603 so that this plan form became well-established a century before the Capitol was built and it continued in frequent use into the eighteenth century. For the plans of two English Houses having the H form, which were erected about the same time as the Capitol see our plate, p. 7.

ADVANTAGES OF H PLAN AND OTHER RELATED PLAN TYPES

The H-shaped plan, the U-shaped plan and the hollow square plan were all planning devices used to avoid unlighted and unventilated interior spaces by giving each room at least one and often two or three outside walls in which windows could be located. In his The Mansions of Virginia, Chapel Hill, 1946, Thomas T. Waterman says (p. 85) of the H plan and its related forms:

As has been pointed out elsewhere, fanciful plans were much in style in England during the seventeenth century, and in provincial areas in the early eighteenth century as well. H, E, U, and T plans were frequently used, the first of which was used in the Capitol in Williamsburg (1699) and was illustrated in Stephen Primatt's The City and Country Purchaser and Builder, published in 1667. The virtues of such a plan were also extolled by Blome in his The Gentleman's Recreation, printed in London in 1709. He observes that "in building of houses long, the use of some rooms will be lost, in that more room must be allowed for Entries and Passages and it requires more doors; and if a building consists of a geometrical square, if the house be large, the middle rooms will want light, and many therefore commend the form of the Capitol Romman H, which, they say, makes it stand firm against the winds, and lets in both light and air and disposes every room nearer to one another."6

TUCKAHOE AND STRATFORD ARE EXAMPLES OF H PLAN IN VIRGINIA; FORMER HAS ENTRANCE IN LONG SIDE OF ONE OF WINGS

The various "alphabetic" plan forms discussed above are all represented in the eighteenth century buildings of Virginia, as well as the hollow square (orig1nal plan for Wren Building) and, of course, the rectangular plan, of which there are many examples. Our previously-consulted plate, p. 7, shows two well-known examples of the H plan, Tuckahoe in Goochland County and Stratford in Westmoreland County. Tuckahoe, a wood dwelling commenced after 1712 and enlarged to the H form shown in the plan sometime after 1730, consists of two typical Virginian two-room-and-central-hall plans, joined by a large central room or salon. It is interesting to note that one of the wings rather than the central hall faces the approach. This is mentioned here because it recalls one of the questions much-debated during the reconstruction of the Capitol, i.e., whether the main entrance to the latter was via the central loggia or the west doorway facing Duke of Gloucester Street. This subject will be treated more at length farther on in the report; suffice it here to note that Tuckahoe, probably in consequence of its piecemeal development; has, like the second Capitol building and perhaps, like the first in its latter days, its main entrance in the long face of one of the wings.

TUCKAHOE PLAN BELIEVED TO HAVE BEEN INSPIRED BY THAT OF CAPITOL; INFLUENCE OF LATTER ON VIRGINIAN ARCHITECTURE

Although the plan of Tuckahoe, like that of the Capitol, could have been inspired by some English example of the H plan, it is more likely that it represents an instance of the influence of the Capitol plan on the architecture of Virginia. Waterman, on p. 86 The Mansions of Virginia, subscribes to this opinion on the basis of the fact that Thomas Randolph, the builder, frequented the Capitol at Williamsburg and was, therefore, well-acquainted with

7

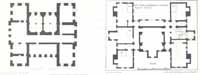

FAWLEY COURT (LEFT) BUILT BY SIR CHRISTOPHER WREN BETWEEN 1684 AND 1688 AND CLAREMONT ESHER, BUILT BY SIR JOHN VANBRUGH FOR HIMSELF IN 1711. THESE HOUSES ARE SHOWN HERE CHIEFLY TO INDICATE THAT THE H PLAN WAS IN USE IN ENGLAND DURING THE PERIOD THE CAPITOL WAS BUILT WHICH STRONGLY SUGGESTS THAT THE DERIVATION OF THE PLAN OF THE LATTER WAS ENGLISH.

FAWLEY COURT (LEFT) BUILT BY SIR CHRISTOPHER WREN BETWEEN 1684 AND 1688 AND CLAREMONT ESHER, BUILT BY SIR JOHN VANBRUGH FOR HIMSELF IN 1711. THESE HOUSES ARE SHOWN HERE CHIEFLY TO INDICATE THAT THE H PLAN WAS IN USE IN ENGLAND DURING THE PERIOD THE CAPITOL WAS BUILT WHICH STRONGLY SUGGESTS THAT THE DERIVATION OF THE PLAN OF THE LATTER WAS ENGLISH.

TUCKAHOE, GOOCHLAND COUNTY (LEFT), WAS BEGUN SHORTLY AFTER 1712 AND ENLARGED TO ITS PRESENT FORM AFTER 1730. STRATFORD, WESTMORELAND COUNTY, WAS ERECTED ABOUT 1725. IT SEEMS VERY LIKELY THAT THE H PLANS OF BOTH OF THESE HOUSES WERE INSPIRED BY THAT OF THE CAPITOL.

8

its form. It is possible that he recognized in this building type the answer to the problem of ventilation which the hot and humid climate of eastern Virginia poses. That buildings of the size and importance of the Governor's Palace and the Capitol should have exerted an influence on the architecture of a land as yet all too scantily provided with impressive structures is not surprising. A documented case in which the Capitol served as a model for emulation is found in an entry of November 18, 1719 in the Vestry Book of St. Peter's Parish in New Kent County (pp. 126, 127). The entry is a specification for the building of a brick courtyard wall about St. Peter's Church. Among other things, it requires "The s'd wall to be in all Respects as well Done as the Capitol wall in Williamsburg."

TUCKAHOE, GOOCHLAND COUNTY (LEFT), WAS BEGUN SHORTLY AFTER 1712 AND ENLARGED TO ITS PRESENT FORM AFTER 1730. STRATFORD, WESTMORELAND COUNTY, WAS ERECTED ABOUT 1725. IT SEEMS VERY LIKELY THAT THE H PLANS OF BOTH OF THESE HOUSES WERE INSPIRED BY THAT OF THE CAPITOL.

8

its form. It is possible that he recognized in this building type the answer to the problem of ventilation which the hot and humid climate of eastern Virginia poses. That buildings of the size and importance of the Governor's Palace and the Capitol should have exerted an influence on the architecture of a land as yet all too scantily provided with impressive structures is not surprising. A documented case in which the Capitol served as a model for emulation is found in an entry of November 18, 1719 in the Vestry Book of St. Peter's Parish in New Kent County (pp. 126, 127). The entry is a specification for the building of a brick courtyard wall about St. Peter's Church. Among other things, it requires "The s'd wall to be in all Respects as well Done as the Capitol wall in Williamsburg."

PLAN OF STRATFORD SIMILAR TO THAT OF TUCKAHOE, BUT MAIN ENTRANCE IS IN CENTRAL CONNECTING ELEMENT

The second Virginia example of an H plan shown on our plate, p. 7 is that of Stratford, a brick mansion built about 1725 by Thomas Lee. The plan, like that of Tuckahoe, is composed of two central hall plans linked by a central salon, but the central-halled wings, in this case, are two rooms deep. It should be noted that, unlike the arrangement at Tuckahoe, the main entrance of Stratford is a doorway in the center of the middle element. From the standpoint of ease of circulation this was the logical place to locate the main entrance and we are, likewise, convinced that the original planner of the Capitol looked upon the central approach, via the loggia, as the most reasonable one in the case of that building. Stratford was built in a single continuous operation, so that the builder was able to place the main entrance in the moat feasible position. In his treatment of Stratford in 9 The Mansions of Virginia (pp. 92-95) Waterman notes the influence on the structure of the baroque work of Sir John Vanbrugh (see house plan, p. 7 of this report) and Nicholas Hawksmoor and suggests that the design of the bui1ding may have resulted from a combination of influences. i.e. literary sources (builders' handbooks) and, as in the case of Tuckahoe, the Capitol at Williamsburg.

ENGLISH ANTECEDENTS OF CAPITOL ARCADE WILL BE INVESTIGATED

Returning to our investigation of the English antecedents of certain of the main features of the Capitol, we will consider the use in English architecture of the loggia or arcade in the period preceding the design and erection of the Williamsburg statehouse. Our purpose in this is to determine, if possible, the source or sources from which the arcade connecting the two wings of the Capitol and bearing enclosed and usable space above it, may have been derived.

CAPITOL ARCADE PRECEDED BY THAT OF WREN BUILDING

We should not fail, at the outset, to mention the fact that the Capitol was not the first building in Virginia in which the arcade was employed, The Wren Building with its arcaded west porch, having been started in 1695 and substantially completed by 1698, preceded it in the use of this feature. A difference of some consequence between the arcades of the two buildings should, however, be pointed out. In the Wren Building a single line of arches and piers forms the outside support of a porch having a rear wall which is unbroken except for a central doorway and, carrying two, full stories above it. In the Capitol three lines of arches support a story-and-a-half super-structure forming a bridge between the two wings of the building and having an open loggia beneath it.

10WHETHER BASED ON ENGLISH MODELS OR ON WREN EXAMPLE ARCADE DERIVED ULTIMATELY FROM ENGLAND

If we believe that the Capitol was designed in England we are led to seek the precedent for its arcaded loggia there rather than in Virginia even though the arcade existed in Williamsburg at the time the Capitol was built. Even if, on the other hand, we were to conclude that the Capitol arcade was derived from that of its near neighbor, the Wren Building, the difference would not be important since, in that case, its ultimate English origin would be but one step removed.

HOUSE SCHEME BY JOHN THORPE HAS BASIC PLAN ARRANGEMENT LIKE THAT OF CAPITOL

Although our search cannot be considered to have been exhaustive, we have succeeded in locating only one example, an architectural design which was never executed, in which the two parallel wings of an H-shaped or, actually, I-T-shaped building (a so-called monogram house in which the architect, John Thorpe, used his own initials), are tied together by a portico (see p. 11}. The portico of this projected Elizabethan house, as in the case of the Capitol loggia, serves as the main approach to the two wings and here, as in the Capitol, there are also secondary entrances. Unlike that of the Capitol, however, this portico is but one bay deep and carries above it a balustraded walk but no enclosed rooms. It is furthermore, of course, constructed of columns rather than arches and piers. However much this house design may differ in character and detailing from the original Capitol, its plan type and scheme for circulation, nevertheless, are similar, basically, to those of the Capitol.

ENGLISH BUILDING TYPES WHICH MAY HAVE INFLUENCED DESIGN OF CENTRAL PART OF CAPITOL

Arcades supporting enclosed spaces above them were plentiful in England at the time the Capitol was being erected. The arcade is a Roman invention so that it was probably first introduced into England in ancient times. It continued to be used there, as elsewhere, in medieval Romanesque and Gothic ecclesiastical

11

SCHEME FOR A HOUSE BY JOHN THORPE, ENGLISH ARCHITECT ACTIVE AROUND 1600. THE HOUSE HAS THE PLAN OF THE CAPITOL AND A CENTRAL CONNECTING MEMBER SERVING AS THE APPROACH TO BOTH WINGS. (FROM HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH HOUSE BY NATHANIEL LLOYD, LONDON, 1931.)

SCHEME FOR A HOUSE BY JOHN THORPE, ENGLISH ARCHITECT ACTIVE AROUND 1600. THE HOUSE HAS THE PLAN OF THE CAPITOL AND A CENTRAL CONNECTING MEMBER SERVING AS THE APPROACH TO BOTH WINGS. (FROM HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH HOUSE BY NATHANIEL LLOYD, LONDON, 1931.)

BELOW RIGHT: THE TOWN HALL AT ABINGDON, ENGLAND, BUILT IN 1677. (FROM ENGLISH HOMES PERIOD IV--VOL. I BY H. AVRAY TIPPING, LONDON, 1920.)

BELOW RIGHT: THE TOWN HALL AT ABINGDON, ENGLAND, BUILT IN 1677. (FROM ENGLISH HOMES PERIOD IV--VOL. I BY H. AVRAY TIPPING, LONDON, 1920.)

BELOW LEFT: THE TOWN HALL AMERSHAM, ENGLAND, BUILT IN 1682. (FROM ENGLISH DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE OF THE XVII AND XVIII CENTURIES BY HORACE FIELD AND MICHAEL BUNNEY, CLEVELAND, 1928.) BOTH BUILDINGS HAVE AN OPEN ARCADED LOGGIA WHICH, LIKE THAT OF THE CAPITOL, CARRIES AN ENCLOSED ROOM ABOVE IT. BOTH ALSO HAVE CUPOLAS SERVING AS BELL TOWERS.

12

ABOVE: BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF LAWNS AND RANGES, DRAWN BY THOMAS JEFFERSON FOR HIS PROJECTED UNIVERSITY AT CHARLOTTESVILLE, CONSTRUCTION OF WHICH WAS BEGUN IN 1817. THIS PERSISTENCE OF THE ARCADE IN VIRGINIA ARCHITECTURE IS EXPLAINED, PROBABLY, BY THE FACT THAT IT WAS RECOGNIZED AS BEING VERY USEFUL IN THE "SUNNY SOUTH." (DRAWING REPRODUCED FROM THOMAS JEFFERSON / ARCHITECT AND BUILDER BY I. T. FRARY, RICHMOND, 1939.)

ABOVE: BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF LAWNS AND RANGES, DRAWN BY THOMAS JEFFERSON FOR HIS PROJECTED UNIVERSITY AT CHARLOTTESVILLE, CONSTRUCTION OF WHICH WAS BEGUN IN 1817. THIS PERSISTENCE OF THE ARCADE IN VIRGINIA ARCHITECTURE IS EXPLAINED, PROBABLY, BY THE FACT THAT IT WAS RECOGNIZED AS BEING VERY USEFUL IN THE "SUNNY SOUTH." (DRAWING REPRODUCED FROM THOMAS JEFFERSON / ARCHITECT AND BUILDER BY I. T. FRARY, RICHMOND, 1939.)

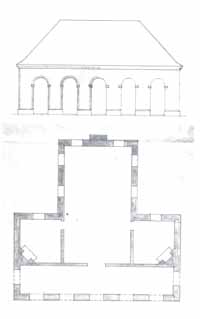

RIGHT: PLAN AND FRONT ELEVATION OF KING WILLIAM COURT HOUSE, ERECTED EARLY IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY. A NUMBER OF

OTHER COURTHOUSES WITH ARCADED FRONTS WERE BUILT IN VIRGINIA, AMONG WHICH THE HANOVER COURTHOUSE (1735) IS NOTEWORTHY. LIKE THOSE OF THE WREN BUILDING AND THE CAPITOL, THESE ARCADES DERIVED FROM ENGLISH ANTECEDENTS. (ELEVATION DRAWING REPRODUCED FROM ORIGINAL IN ARCHITECTURAL SKETCHBOOK OF SINGLETON P. MOOREHEAD.)

RIGHT: PLAN AND FRONT ELEVATION OF KING WILLIAM COURT HOUSE, ERECTED EARLY IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY. A NUMBER OF

OTHER COURTHOUSES WITH ARCADED FRONTS WERE BUILT IN VIRGINIA, AMONG WHICH THE HANOVER COURTHOUSE (1735) IS NOTEWORTHY. LIKE THOSE OF THE WREN BUILDING AND THE CAPITOL, THESE ARCADES DERIVED FROM ENGLISH ANTECEDENTS. (ELEVATION DRAWING REPRODUCED FROM ORIGINAL IN ARCHITECTURAL SKETCHBOOK OF SINGLETON P. MOOREHEAD.)

THE PLAN OF THE KING WILLIAM COURT-HOUSE (FROM A MEASURED DRAWING BY GEORGE S. CAMPBELL ) IS MORE OR LESS TYPICAL OF VIRGINIA COURTHOUSE PLANS SINCE SIMILAR FUNCTIONS ARE PERFORMED IN ALL OF THESE BUILDINGS. IN THE ISLE OF WIGHT COURT-HOUSE AND THE CHOWAN COUNTY COURTHOUSE, EDENTON, NORTH CAROLINA (ILLS., PP. 18, 19) THE COURT ROOMS, ESSENTIALLY THE SAME IN FORM AND USE AS THE GENERAL COURT ROOM OF THE CAPITOL, WERE GIVEN, LIKE THE LATTER, SEMI-CIRCULAR ENDS.

13

architecture. With the introduction into England by Inigo Jones and others of the form vocabulary of the Italian Renaissance, the arcade again became a frequently-used feature. Our plate, p. 11, shows two English town halls built only a few years before the Capitol. In these buildings, as in the Capitol, open arcades carry enclosed spaces above them and these were used, no doubt, for much the same purpose as the Conference Room of the Capitol which occupies the space over its arcade. To be sure, the town halls have no flanking wings, but they do bear a close resemblance to the central element of the Capitol, even to the possession of cupolas over their centers. In detailing, of course, the pilastered Renaissance facades of the Abingdon town hall are far more ornate than the restrained faces of the Capitol but the Amersham structure, on the other hand, despite its stone trim, has a simplicity which links it, in feeling, with the Capitol. We have reason to suspect that buildings of this type exercised an influence on the design of the Capitol.

USEFULNESS OF ARCADED PORCH IN VIRGINIA

A few words should be said about the appropriateness of the use in Virginia of the arcaded porch. This feature which, as we have said, originated in Italy, a land of arched and collonaded porticoes, was there eminently practical as well as highly ornamental, since it furnished pedestrians protection not only from the rain but also, in that southern climate, from the intense heat of the sun. Though less necessary for the latter reason in England, it was once more, in Virginia, very useful since it provided shade which in the summer heat of that country is very welcome.

14

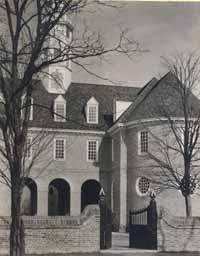

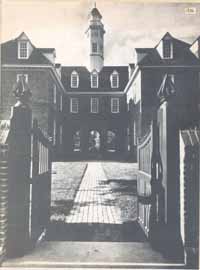

THE SEMI-CYLINDRICAL SOUTH ENDS OF THE RECONSTRUCTED CAPITOL

15

In using it in public meeting places like courthouses, the main building of the College and the Capitol, in all of which numbers of people were likely to pause for conversation or to discuss business, the colonists adapted their buildings to the climate of the land. These loggias continued to be used, indeed, long after the colonial period ended, a notable example of this use being the arcaded covered ways of the east and west ranges of Thomas Jefferson's University of Virginia (see drawing, p. 12).

THE SEMI-CYLINDRICAL SOUTH ENDS OF THE RECONSTRUCTED CAPITOL

15

In using it in public meeting places like courthouses, the main building of the College and the Capitol, in all of which numbers of people were likely to pause for conversation or to discuss business, the colonists adapted their buildings to the climate of the land. These loggias continued to be used, indeed, long after the colonial period ended, a notable example of this use being the arcaded covered ways of the east and west ranges of Thomas Jefferson's University of Virginia (see drawing, p. 12).

CURVED ENDS OF CAPITOL, ITS MOST STRIKING FEATURES, HAD NO COUNTERPARTS IN VIRGINIA; EXAMPLES OF CIRCULAR BUILDINGS IN COLONY

By all odds the most striking features of the Capitol were the half-cylindrical south ends of its wings which had no counterparts in the architecture of Virginia at the time of their erection. Roughly-cylindrical tower windmills and some cylindrical plantation outbuildings, such as the ice houses at Rosewell and Toddsbury (Gloucester County) and Westover (Charles City County); the quite exceptional slave quarter at Keswick (Powhatan County) and the dovecotes at Westover and Shirley (Charles City County), were, in fact, almost the only buildings erected during the colonial period in Virginia which were not straight-sided. Again we must turn to the mother country to find the basis for the curved ends of the Capitol wings and for these other cylindrical structures.

CYLINDRICAL STRUCTURES NOT UNCOMMON IN ENGLAND AND CAPITOL ARCHITECT COULD HAVE DERIVED INSPIRATION FROM THEM

We find upon investigation that cylindrical and semi-cylindrical buildings were not rare in the architecture of England. On the two illustration plates which follow (pp. 16 and 17) we present a few selections from many extant English examples of buildings in which the cylindrical form plays an important role. These suggest the rounded ends of the Capitol sufficiently to justify us in venturing the assertion that had the Capitol been erected in England it would scarcely have aroused wonder or curiosity because of the unfamiliarity of its shape.

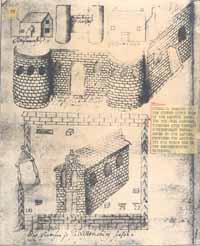

16THE BUILDING OF STONE CASTLES BEGAN IN ENGLAND AFTER THE NORMAN CONQUEST, THE EARLIEST OF THEM, THE TOWER OF LONDON, HAVING BEEN COMPLETED BEFORE 1087. TOWERS OR TURRETS ERECTED AT SALIENT POINTS OF THE ENCLOSING WALLS ENABLED BOWMEN TO SHOOT AT ATTACKING FORCES. THESE TURRETS WERE SOMETIMES SQUARE IN SECTION AND SOMETIMES ROUND. THE LATTER TYPE WAS FREQUENTLY USED SINCE IT ENABLED DEFENDERS TO OBSERVE AND TO SHOOT THROUGH CROSS-SLITS PLACED AT SEVERAL POINTS IN THE CYLINDER'S CIRCUMFERENCE. BODIAM CASTLE (TOP PICTURE, TAKEN FROM NATHANIEL LLOYD'S A HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH WAS SURROUNDED BY A MOAT AND ENTERED THROUGH A FORTIFIED GATE-HOUSE APPROACHED VIA A DRAWBRIDGE. WOULD-BE INVADERS WERE SUBJECT TO FLANK ATTACK FROM THE CYLINDRICAL TOWERS.

BY THE TIME THE GATEHOUSE OF WOLFETON, A LARGE TUDOR MANOR HOUSE IN DORSET (MIDDLE AND LOWEST PICTURES, TAKEN FROM COUNTRY LIFE, AUGUST 6, 1953) WAS BUILT IN 1534, THE NEED FOR DEFENSIVE TOWERS HAD LARGELY PASSED, SO THAT IT HAS BEEN SUGGESTED THAT THESE MAY BE EARLIER FEATURES INCORPORATED INTO THE TUDOR STRUCTURE. THE UPPER PARTS OF THE TOWERS WERE ONCE DOVECOTES AND AN OLD ENGRAVING SHOWS THAT THEIR CONICAL ROOFS WERE FORMERLY STEEPER.

WITH THE END OF CASTLE BUILDING IN ENGLAND THE CYLINDRICAL AND HALF-CYLINDRICAL FORMS CONTINUED TO BE USED AS ARCHITECTURAL FEATURES HAVING NO DEFENSIVE PURPOSE AND WE FIND THEM LATER IN WORKS BY ENGLISH RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTS SUCH AS JONES, WREN, VANBRUGH AND OTHERS. THEY WERE ALSO OFTEN EMPLOYED IN MORE PURELY FUNCTIONAL STRUCTURES LIKE FARM BUILDINGS OF VARIOUS SORTS (SEE PICTURES ON OPPOSITE PAGE). IT BECOMES EVIDENT THAT CYLINDRICAL AND SEMI-CYLINDRICAL SHAPES HAD BEEN FAMILIAR ONES IN ENGLISH ARCHITECTURE FOR CENTURIES BEFORE THE CAPITOL WAS BUILT. IT IS NOT SURPRISING, THEREFORE, THAT THE ARCHITECT OF THAT BUILDING SHOULD HAVE MADE USE OF HALF CYLINDERS IN ITS DESIGN.

17 [Sketches]

[Sketches]

LEFT: GRANITE BARN AT SOUTH COOMBES HEAD, CORNWALL, ENGLAND. (FROM REGIONAL ARCHITECTURE OF THE WEST OF ENGLAND BY A. E. RICHARDSON AND C. LOVETT GILL, LONDON, 1924.) THE AUTHORS SPEAK 0F THIS AS "ONE OF THE FINEST EXAMPLES OF EARLY EIGHTEENTH CENTURY MASONRY IN THE PROVINCES." THE BARN HAS TWO OF THE MAIN FEATURES OF THE CAPITOL, THE ARCADE AND THE HIP-ROOFED APSIDAL END. THOUGH BUILT LATER THAN THE CAPITOL, IT IS UNQUESTIONABLY COMPOSED OF TRADITIONAL FORMS.

THE PICTURE IMMEDIATELY BELOW, OF TWO OAST-HOUSES (HOP DRYING KILNS ) NEAR COWBEECH IN SUSSEX, ENGLAND WAS REPRODUCED FROM ROWLAND C. HUNTER'S OLD HOUSES IN ENGLAND, 1930. THESE BUILDINGS, WHICH THE AUTHOR DOES NOT DATE, PROBABLY STEM FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, WHEN MANY KILNS OF THIS TYPE WERE BUILT, THOUGH OAST-HOUSES EXISTED BEFORE THAT. THE BRICKWORK OF THESE BUILDINGS WAS LAID UP IN FLEMISH BOND, ACCENTED BY GLAZED HEADERS. THE STRUCTURES SHOWN HERE NO LONGER SERVE THEIR INTENDED USE AND HAVE LOST THE FUNNEL SHAPED VENTS IN WHICH THE ROOFS ONCE TERMINATED. THE WALLS, FURTHERMORE, WERE ORIGINALLY WITHOUT OPENINGS, THE WINDOWS HERE BEING A MODERN INSTALLATION.

THE TWO LOWER PICTURES AT THE RIGHT, FROM THE NOVEMBER 26, 1953 ISSUE OF COUNTRY LIFE, SHOW TWO OF SOME HUNDREDS OF CIRCULAR STONE DOVECOTES WHICH STILL EXIST IN SCOTLAND. THE LEFT HAND EXAMPLE IS AT DIRLETON CASTLE IN EAST LOTHIAN WHILE THE OTHER IS AT PITTENCRIEFF PARK, DUNFERMLINE, FIFE. THREE OR FOUR HUNDRED YEARS AGO PIGEONS WERE, IN SCOTLAND, ALMOST THE ONLY SOURCE OF FRESH MEAT IN WINTER, SO THAT EVERY CASTLE, MONASTERY OR GREAT MANOR HOUSE THERE HAD A DOVECOTE TO SUPPLY IT WITH THE BIRDS.

18A MORE STRIKING EXAMPLE OF THE INFLUENCE OF THE CAPITOL ON (THE SUBSEQUENT ARCHITECTURE OF VIRGINIA COULD SCARCELY BE FOUND, PROBABLY, THAN THAT REVEALED IN THE FORM OF THE COURT ROOM WING OF THE OLD ISLE OF WIGHT COURTHOUSE IN SMITHFIELD, WHICH STEMS FROM THE MIDDLE OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY. THIS BUILDING HAS THE T PLAN CHARACTERISTIC OF VIRGINIA COURT HOUSES BUT, QUITE UNTYPICALLY, THE COURT ROOM END HAS BEEN MADE SEMI-CIRCULAR IN IMITATION OF THE ROUNDED SOUTH ENDS OF THE TWO WINGS OF THE CAPITOL. THE HALF-CONICAL HIPPED ROOF OF THE END HAS NEARLY THE SAME PITCH (SLIGHTLY MORE THAN 45°) AS THE ROOF OF THE CAPITOL; THE MODILLION CORNICES OF THE TWO BUILDINGS ARE VERY SIMILAR TO EACH OTHER AND THE BRICKWORK OF BOTH, ABOVE THEIR WATERTABLES, IS LAID IN FLEMISH BOND. IT SHOULD BE ADDED THAT THE UPPER WINDOWS OF THE CURVED END OF THE COURT HOUSE HAVE THE SAME NUMBER OF LIGHTS AS THE SECOND STORY WINDOWS OF THE CAPITOL. THE CORRESPONDENCE OF THESE ORIGINAL FEATURES OF THE COURT-HOUSE WITH THE RECONSTRUCTED DETAILS OF THE CAPITOL SERVES FURTHER TO DEMONSTRATE THE AUTHENTICITY OF THE LATTER.

THE LOWER PICTURE SHOWS THE STRUCTURE WITH NINETEENTH CENTURY ACCRETIONS WHILE THE UPPER ONE SHOWS IT AS IT IS AT PRESENT, WITH THESE ADDITIONS REMOVED. THE BUILDING IS NO LONGER A COURT HOUSE. THE FRONT PORTION BEING USED FOR OFFICES AND THE COURT ROOM REMAINING UNOCCUPIED. THE ILLUSTRATIONS ARE FROM THE H.A.B.S. COLLECTION OF PHOTOGRAPHS, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS.

19 [Interior photograph - Chowan Courthouse]

[Interior photograph - Chowan Courthouse]

ANOTHER EIGHTEENTH CENTURY COURTHOUSE WHICH DEMONSTRATES UNMISTAKABLY THE INFLUENCE OF THE CAPITOL ON THE SUBSEQUENT DESIGN OF STRUCTURES DEVOTED TO GOVERNMENTAL USES IS THE CHOWAN COUNTY COURTHOUSE IN EDENTON, NORTH CAROLINA. THE PHOTOGRAPH (FROM THE H.A.B.S. COLLECTION) IS AN INTERIOR VIEW OF THE APSIDAL TERMINATION OF THE COURT ROOM SHOWN IN THE PLAN BELOW. THE LATTER WAS TAKEN FROM THE EARLY ARCHITECTURE OF NORTH CAROLINA BY FRANCES B. JOHNSTON AND THOMAS T. WATERMAN, CHAPEL HILL, 1941.

[Plan]

[Plan]

WE CAN D0 NO BETTER, PROBABLY, THAN QUOTE WATERMAN ON THE SUBJECT OF THIS COURT HOUSE AND ITS DESIGN DERIVATION SINCE, HAVING WORKED ON THE PLANS FOR THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE CAPITOL, HE WAS INTIMATELY ACQUAINTED WITH THE LATTER. OF THE COURT HOUSE HE SAYS: "IT WAS BUILT IN 1767, AND IS ATTRIBUTED TO GILBERT LEIGH, A RESIDENT OF EDENTON, SAID TO HAVE COME FROM WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA. THE GENERAL PLAN, WITH CENTRAL COURT ROOM AND FLANKING OFFICES, IS TYPICAL OF TIDEWATER VIRGINIA. AN EXACT PARALLEL IN PLAN…IS THE FORMER ISLE OF WIGHT COURT HOUSE AT SMITHFIELD, VIRGINIA… THE ORIGIN OF BOTH BUILDINGS CAN CERTAINLY BE FOUND IN THE CAPITOL AT WILLIAMSBURG, WITH ITS APSIDAL GENERAL COURT ROOM AND HOUSE OF BURGESSES. EVEN THE JUDGE'S CHAIR AND PANELED WAINSCOT AT EDENTON ARE PARALLEL TO THESE FEATURES OF THE WILLIAMSBURG CAPITOL. … THIS WOULD MEAN THAT LEIGH KNEW THE CAPITOL BEFORE THE FIRE OF 1747, AS ALL OF THIS DETAIL PERISHED THEN."

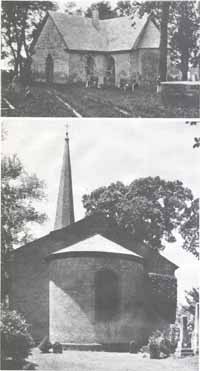

20THE TWO EIGHTEENTH CENTURY CHURCHES SHOWN HERE, TRINITY CHURCH, DORCHESTER COUNTY, MARYLAND (ABOVE) AND ST. PAUL'S CHURCH, EDENTON, NORTH CAROLINA BOTH HAVE SEMI-CIRCULAR APSES RESEMBLING THOSE OF THE CAPITOL. ACCORDING TO SWEPSON EARLE, FROM WHOSE BOOK, THE CHESAPEAKE BAY COUNTRY, BALTIMORE, 1938, OUR PHOTOGRAPH WAS TAKEN, "OLD TRINITY" DATES BACK TO ABOUT 1680 WHILE THOMAS T. WATERMAN TELLS US IN THE ARCHITECTURE OF NORTH CAROLINA (FRANCES B. JOHNSTON AND THOMAS T. WATERMAN, CHAPEL HILL, 1941) THAT ST. PAUL'S CHURCH WAS STARTED IN 1736 AND ITS SHELL AND ROOF COMPLETED BY 1745.

THE DESIGN OF TRINITY COULD NOT WELL HAVE BEEN INFLUENCED BY THE CAPITOL, IF EARLE IS CORRECT IN HIS DATING OF IT, BECAUSE IT WAS ERECTED ALMOST A QUARTER CENTURY BEFORE THE BUILDING OF THE FIRST CAPITOL. OF ST. PAUL'S, WATERMAN SAYS: "ITS FORM IS UNUSUAL IN AN AREA OF COUNTY CHURCHES WHERE … CUSTOM AVOIDED A CHANCEL APSE. NO APSE IS KNOWN EVEN ON SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY CHURCHES IN VIRGINIA, AND THE ONLY REFERENCE TO ONE THERE IS IN A DRAWING IN THE FULHAM PALACE ARCHIVES … IT WOULD SEEM QUITE POSSIBLE THAT THE PLANS FOR ST. PAUL'S CAME FROM ENGLAND… ."

THE SEMI-CIRCULAR APSE, OF COURSE, WAS A COMMON FEATURE IN THE CHURCH ARCHITECTURE OF EUROPE FROM THE DAYS OF THE EARLY CHRISTIAN BASILICA ONWARD THROUGH THE ROMANESQUE AND GOTHIC PERIODS TO THE TIME OF THE BUILDING OF THE TWO CHURCHES ILLUSTRATED HERE. IT IS LIKELY, THEREFORE, THAT THEY STEM FROM THIS LONG-ESTABLISHED CHURCH FORM RATHER THAN FROM THE EXAMPLE OF THE CAPITOL, WHICH MAY ITSELF, HAVE BEEN INFLUENCED BY THIS TRADITIONAL USE OF THE APSE FORM.

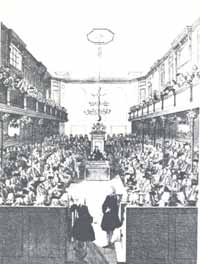

21OLD ENGLISH COURT ROOM MAY HAVE BEEN ACTUAL MODEL FOR APSES OF CAPITOL

Thus far, in our illustrations and text, we have considered possible English antecedents of the half-cylindrical south ends of the Capitol from the standpoint of the external resemblance between the latter and the former. In addition, an English interior has come to light which so strongly resembles the apsidal end of the Capitol Court Room as to lead us to believe that it may have been the actual model after which the original Court Room, with its half-cylindrical end, may have been designed. The example in question is the court room of the Doctors' Commons in London. Two drawings of this are reproduced on pp. 277 and 278 of Part 2 of this report.

APSIDAL SHAPE OF SOUTH ENDS OF WINGS OF CAPITOL WAS FOLLOWED IN THREE COURTHOUSES BUT OTHERWISE NOT IMITATED

However great the prestige of the first Capitol may have been, it cannot be said that its most striking features, the half-cylindrical ends, were widely copied in the colonies, possibly because curved forms are not so readily executed in brickwork as rectangular ones. Nevertheless, two courthouse buildings still exist in which the imitation of these features of the Capitol is very apparent and we have the original specification for a third one, which has since disappeared. In the structure in Smithfield which served from l750 to 1800 as the Isle of Wight CourthoUse {see photos and discussion, p. 18) the resemblance of the curved end to those of the Capitol is so close as to remove all doubt as to its provenance. It is evident, likewise, that the County Courthouse in Edenton, North Carolina (p. 19) was designed under the direct influence of the Capitol and here the imitation of the interior treatment of the apsidal end of the Chamber of the House of Burgesses is readily discernible. The specification mentioned above stems from 1740 and lists the dimensions and various features of a courthouse to be erected in Lancaster County. It provides, among other things, that the building shall have "one compas End." Since only circles or parts of circles can be drawn 22 with a compass, this "compas End" must have been semi-circular.*

As for the curved apses of the two churches shown on p. 20, it is probable that these are lineal descendants of countless examples of this feature which have been used on churches since the early days of the Christian church. The most one might say is that the existence of the shape on the Capitol influenced the builders to choose a form long characteristic of European church architecture but which was rarely used in the South in colonial times.

OCTAGONAL STRUCTURES BECAME MORE NUMEROUS IN VIRGINIA THAN CIRCULAR

It should be pointed out that while circular shapes, except in minor details, were not numerous in the buildings of Virginia (see p. 15), the octagon and half-octagon were used fairly frequently. The octagon could be looked upon as a straight-sided first cousin of the circle since, like the latter, it is concentric and symmetrical and possesses much of the feeling of the circle. It is, of course, far simpler to build, a consideration which probably accounts for the fact that it was more often employed. The Magazine in Williamsburg, built in 1715, has this form. I twas used in garden houses and other smaller outbuildings (the reconstructed structure in the service court of the Governor's Palace which, for want of a more specific title, is designated as the "Hexagonal" is, of course, six-sided). The shape was later a favorite one with Thomas Jefferson who made numerous building designs utilizing the full or half octagon. It should be remarked, in concluding this discussion of circular and quasi-circular structure in Virginia, that Jefferson's great cylindrical building, the Rotunda of his University at Charlottesville, was based on neither Virginian nor English models but, rather, on the form of the ancient Pantheon in Rome.

PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED IN RECONSTRUCTION OF CAPITOL

25BRIEF REVIEW OF HISTORY OF CAPITOL; FIRE OF 1747 AND ERECTION OF SECOND BUILDING; REMOVAL OF SEAT OF GOVERNMENT TO RICHMOND

It will be an aid to the understanding or some of the questions to be discussed in this section and in the report generally if we are in possession of a few facts on the history of the Capitol or, rather, the Capitols subsequent to the completion of the first building in 1704. This building was burned in 1747 but parts of its walls, we believe, remained standing and were utilized in the construction of the second building. This was begun in 1751 and completed in 1753. The second Capitol, the scene of many significant events, remained in use as a statehouse until 1779, when the seat of government was removed to Richmond.

USES SERVED BY SECOND CAPITOL DOWN TO 1832, WHEN ITS REMAINING HALF BURNED

"During the fifty years which followed, the Capitol served variously as a meeting place of the Court of Admiralty and of the District Chancery Court, as a law school; a military hospital, and as a grammar school. In 1793 an act of the Assembly authorized the sale of the east wing to raise funds for the repair of the west wing. In 1832 the remaining portion of the Capitol was destroyed by fire.

SITE ACQUIRED BY A.P.V.A. WHICH PRESENTS IT TO COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG INC. IN 1928

"In 1839 a 'female academy' was erected on the Capitol site. In 1881 the last traces of this building were removed. In 1897 the site was presented by the Old Dominion Land Company to the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. This association protected and preserved the old foundations of the Capitol until July 16, 1928, when it presented the land to Colonial Williamsburg, Incorporated.

STUDY OF SITE

"In 1928 the old foundations were excavated and archaeological investigation undertaken. Following an extensive research campaign, 26 the Capitol was rebuilt upon its original foundations."*

REASONS FOR CHOICE OF FIRST CAPITOL AS THE ONE TO BE REBUILT; MORE DETAILED INFORMATION CONCERNING IT EXISTED THAN IN CASE OF SECOND

It should be stated at the outset that the first Capitol building was chosen for reconstruction rather than the second, in which so many events occurred which contributed to the outbreak of the War for Independence, for several reasons. Chief among these was the fact that, thanks to the availability of the acts and other measures of the General Assembly giving directions for the building of the Capitol (p. 1), a great deal was known about the first building. Nothing at all comparable in the way of detailed information existed concerning the second building, so that a reconstruction of that structure of the degree of authenticity of the present one, could never have been made.

FIRST BUILDING A "PURER' AND MORE UNIFIED STRUCTURE THAN THE SECOND

A further consideration which carried weight in arriving at the decision to rebuild the original edifice had to do with the relative architectural merit of the two structures. The first Capitol building was built in one operation and was a unified structure, as well as being a unique one. The second, though built upon the ruins of its predecessor, was a much altered version of this and may well be said to have been a transitional or a nondescript building. Stylistically, then, the first building was much superior to the second.

FIRST CAPITOL A TRAINING GROUND IN THE CONDUCT OF DEMOCRATIC LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLIES

Returning to the relative significance which the two buildings had, politically, and, admitting the importance and dramatic character of the events which took place in the second one, it 27 behooves us to point out, as does Stanley M. Pargellis in his informative article, "The Procedure of the Virginia House of Burgesses" (William and Mary Quarterly, Second Series, Vol. VII, April and July, 1927) that the activities which, took place in the first building also merit our attention. We should not forget that it was in this building, as well as in the statehouses at Jamestown, that the colonists gained experience in democratic parliamentary procedures, laid the groundwork for the conduct of future representative assemblies in America and, for the matter, acquired the political maturity and acumen which enabled them, when the final culminating crisis in the relations of the dominion with the mother country came, to act with wisdom and decision.

DESPITE THE EXISTENCE OF SPECIFICATIONS FOR ERECTION OF CAPITOL, CERTAIN POINTS IN ITS DESIGN REMAINED IN DOUBT WHEN RECONSTRUCTION WAS UNDERTAKEN

Despite the fact that the legislative acts of 1699 and 1701 specified the type of plan the Capitol was to have and the dimensions of each of its three parts; the thickness of its walls; the interior divisions and many of the exterior and interior details (see Appendix for a verbatim transcript of these acts), the architects in charge of the reconstruction of the building were nonetheless confronted by a number of puzzling questions when they undertook their investigation into the nature of the original structure, preparatory to the making of the working drawings. We will outline here the chief points which were in doubt and the decisions which were reached respecting them.*

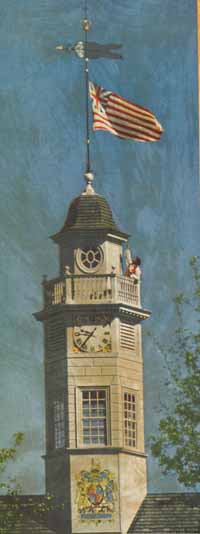

28DETERMINATION OF WHICH FACE WAS FRONT OF CAPITOL NECESSARY IN WORKING OUT CERTAIN POINTS IN ITS DESIGN; I.E. LOCATION OF QUEEN'S ARMS

A matter which was the subject of considerable study and debate was the question as to which of the building's four facades had been looked upon as the front in the eighteenth century. This was a consideration of importance for a number of reasons. On it hinged the decision as to which of the faces of the cupola was to receive the Queen's Arms since, according to an entry on p. 217 of the Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1702-1712, it was ordered on June 7, 1706 "… That the Queens arms be painted upon the front of the Cupolo of the Capitol" Since the cupola was hexagonal, only two sides could be made parallel with either of the two main axes of the building. Therefore, it was important to determine which face of the building had been the front in order to know how to turn the faces of the cupola. If, for example, either the north or south face were found to be the front, the cupola would be placed so that two of its faces paralleled the east-west axis.

LOCATION OF BRICK SHIELD DEPENDED ON INDENTIFICATION OF MAIN FRONT

This information was also needed to enable the architects to locate the carved brick shield of which Governor Francis Nicholson speaks in a communication of March 3, 1705, now in the Public Record Office, London (C05-#1314):

… he [James Blair] had the Assurance (to give it no worse name) to reflect upon what I had ordered to be put upon the Capitoll which was done in cutt bricks, & first showed on the day that (according to my duty) I proclaimed her Maty [Majesty], at top there was cut the Sun, Moon, and the planet Jupiter, and underneath thus HER MAJESTY QUEEN ANNE HER ROYALL CAPITOLL…It seems very likely that this device would have been placed, originally, on the facade which was looked upon as the front of the building. 29

SMOOTH FUNCTIONING OF BUILDING DICTATED USE OF "PIAZZA" AS MEANS OF APPROACH TO TWO WINGS OF CAPITOL

Ease of use would surely, in the beginning, at least, have dictated that the building be entered via the "piazza" connecting the two wings and we have every reason to believe that the arcade was intended, originally, as such a focal point from which the two parts of the building could be reached directly. It would have required only a rudimentary sense of sound planning on the Part of the builders of the Capitol to cause them to decide against the designation of either the east or west doorway as the main entrance for the reason that, if one of these were so chosen, the ground floor room of that wing, either the hall of the House of Burgesses or the General Courtroom, would have become a passageway for persons having business to transact in the other wing. Such use would also, of necessity, have led to some modification of the internal arrangements of one or the other of these two important chambers.

ACCEPTING THIS REASONING, THE ARCHITECTS HAD TO DECIDE WHETHER NORTH OR SOUTH FRONT HAD BEEN THE MAIN APPROACH; EVIDENCE POINTED TO LATTER AS FRONT FACADE

Thus, the architects were bound to conclude that the building had originally been approached from either the north or the south, the two sides, that is, from which the central arcade could most easily be reached. The question then remained as to which of these two sides had been looked upon as the main approach; They believed, at first that the north side had served as the front, inasmuch as the engraver of the Bodleian plate had chosen to depict that side of the building. It was argued that, since he had shown the fronts of the Wren Building and the Palace, he would, in all likelihood, also have shown the main facade of the Capitol. Documentary evidence, nevertheless, militated against the acceptance of the north facade as the de facto front of the building. A deed given by Claude Revierre and wife, executors of Joseph Chermoson, to David Cunningham, dated

The Bodleian copper plate from which the above representation of the Capitol was taken, carries on it, also, views of the buildings of the College of William and Mary of its flora and fauna. It has never been possible to date the engraving exactly. The plate, or, more accurately, perhaps, the sketches from which the engraver who made the plate worked, it seems, must have been made between 1733, the completion date of the President's House of the College, which is shown on the plate, and 1747 when the first Capitol burned. This Bodleian plate representation of the Capitol proved to be an invaluable aid to the architects in the determination of the general character of the building and of a number of its details.

The Bodleian copper plate from which the above representation of the Capitol was taken, carries on it, also, views of the buildings of the College of William and Mary of its flora and fauna. It has never been possible to date the engraving exactly. The plate, or, more accurately, perhaps, the sketches from which the engraver who made the plate worked, it seems, must have been made between 1733, the completion date of the President's House of the College, which is shown on the plate, and 1747 when the first Capitol burned. This Bodleian plate representation of the Capitol proved to be an invaluable aid to the architects in the determination of the general character of the building and of a number of its details.

The presence in the engraving of the two chimneys, not shown on our drawing of the north elevation, p. 131, requires a few words of explanation. For reasons of fire safety chimneys were omitted from the reconstructed Capitol. By 1723 the danger of the destruction of the records by dampness came so far to outweigh the fear of fire that the House of Burgesses, complying with the recommendation of the Governor and Council, resolved "to build stacks of Chimneys with two Fire places in each Chimney at the North end of the Capitol… ." (Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1712-1726, p. 390). The two foundations indicated in green on the archaeological plan, p. 41 are presumably the remains of these stacks, although they are indicated as being later in period than the squared-off south ends of the second Capitol.

31

May 8, 1712,* was discovered, which runs, in part, as follows:

… All those two lots of land with dwelling house and outhouses which was the testators at the time of his death, lying and being in the City of Williamsburg, on the back side [italics ours] of ye Capitol near ye Public Gaol, designed in the plot of the said city by the figures 279; 280…We know that the Gaol was located north of the Capitol so that as early as 1712 the north side, evidently, was looked upon as the rear of the building and, of course, the side opposite the rear must have been considered the front. So the architects, with good reason, fixed upon the south face as having been the front of the building during the period to which the structure was being reconstructed.

A RESOLUTION ORDERED THE CLOSING OF THE NORTH ARCHES; WAS THIS EVER CARRIED OUT?

This conclusion was further reinforced by a resolution of November 5, 1720 which is recorded in the Journal of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1712-1726, p. 255:

Resolved That Mr. Speaker and Mr. Clayton who are Impowered by Act of Assembly to repair and amend the Capitol, be desired Immediately to Imploy the workmen to Close up North Arches in the Piassa of the Capitol.The architects assumed that this resolution was carried into execution although a certain circumstance conflicts with that conclusion, viz., that the Bodleian plate view of the Capitol shows the arches still open. We know that the Bodleian plate must have been made after the erection of the President's House of the College in 1732-33 because that building is depicted on it. It was probably also made before l747 when the first Capitol was destroyed by fire. Evidently, unless the artist and the engraver chose to show an early condition of the Capitol, the closing of the north arches was never carried 32 out in the first building.

EVIDENCE THAT ARCHWAYS WERE CLOSED IN SECOND CAPITOL, IS, HOWEVER, POSITIVE

There is, on the other hand plenty or evidence to prove that both the north and south arches were closed in the second building, probably, however, by means of doors rather than by the bricking up or the arches, as was contemplated in the order of 1720, but, we believe, never carried out. In this building, as we have remarked, the west side was forced into serving as the principal facade by the application to the front of a two-tiered portico and the closing of the external arches of the central porch was doubtless intended, by discouraging their use as a means of entry, further to consolidate the position of the west front as the main entrance side.

EVIDENCE IS BOTH LITERARY AND PICTORIAL; STATEMENTS BY TRAVELLERS

The evidence which indicates that the outside arches of the central cross gallery or "piazza" were closed and that this space became, in effect, a room is both literary and pictorial. As to the first, we have in the journal kept by Ebenezer Hazard, a traveller who paid Williamsburg a visit in 1777,* the following reference to the one-time open porch:

Upon entering the Capitol you get into a Room in which the Courts of Justice are held; it is large & conveniant… Opposite to the Door by which you enter this Room (in another Apartment, which is a Kind of Hall)** is an elegant white marble pedestrian Statue of Lord Botetourt in his Robes….33

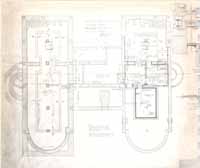

DRAWING BY BENJAMIN LATROBE SHOWING CONDITION OF "PIAZZA IN 1796.

DRAWING BY BENJAMIN LATROBE SHOWING CONDITION OF "PIAZZA IN 1796.

In addition to this, Johann Schoepf described the Capitol in 1783 and made note of the statue which stood "in one of its lower rooms ." Finally, Isaac Weld visited the Capitol in 1796 and stated that "In the Hall of the capitol stands a maimed statue of lord Botetourt."

PICTORIAL EVIDENCE; DRAWING BY LATROBE

Pictorial evidence pointing to the closing off of the arches is contained in a drawing of the "piazza" made by the celebrated architect-engineer, Benjamin Latrobe when, on a mission in this vicinity in 1796 to revamp the seventeenth century former 34 gubernatorial residence, Greenspring, he visited Williamsburg.* Latrobe's drawing (reproduction on preceding page) shows what is evidently the southern half of the arcade since it was there that the Botetourt statue is believed to have stood (see plan of second building, Diagram A, p. 46). The drawing clearly indicates that the space in question was plastered and the transom in the archway at the left suggests that doors had been used to close it off from the outside. The jambs of the arches at the right, half plastered and half showing brickwork, reinforce this hypothesis; the door frames, evidently, had served to divide the interior plaster from the exterior brick-work of the piers. The fact that the piers, both right and left, are half plastered and half brickwork suggests two possibilities, i.e., that only the southern half of the former "piazza" was enclosed or in the second building the middle line of arches had been eliminated.

MEANING OF STATEMENT CONCERNING DIMENSIONS OF CROSS GALLERY NEVER COMPLETELY CLARIFIED

Before leaving the subject of the central arcade or cross gallery it should be mentioned that the building Act of 1699 (see Appendix) stipulated that "the two parts of the building shall be joyned by a Cross Gallery of thirty foot long and fifteen foot wide each way… raised upon Piazzas and built as high as the other parts of the building." The expression, "fifteen foot wide each way" puzzled the architects and they never did attain to absolute certainty as to its meaning. Since, however, the height of the first story of the structure is specified in the act as fifteen feet it is likely that the prase was intended to mean that the arcade should be made fifteen feet wide (north-south dimensions) and fifteen feet high.

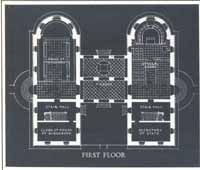

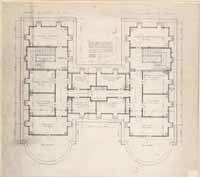

35GALLERY WIDTH DOUBLED BEFORE CONSTRUCTION OF ORIGINAL BUILDING WAS BEGUN

Plan I of Diagram A, p. 46 purports to show the main floor of the building as originally specified. The arcade or cross gallery is represented as being one bay wide. We know that the arcade was never built this way since, before the erection of the structure was begun, the Act of 1701 was passed by the General Assembly (Appendix) and this contained certain additions and amendments to the original one. One of the changes specified was "that the cross building betwixt the two main buildings be of the same breadth with the maine buildings…" The building, evidently, as originally built, had a two-bay, ca. 30-foot-wide cross gallery and the architects reconstructed it that way. This state of the cross gallery is shown on plan II of Diagram A, which represents the main floor of the building as it was originally built.

WHY DID THE BUILDERS OF THE CAPITOL TURN THE "ARCHITECTURAL FRONT" TOWARD THE NORTH AND THEREBY NEGATE THE PROBABLE INTENTION OF THE ARCHITECT?

The theory has been advanced that the north facade of the Capitol which the maker of the Bodleian plate depicted and therefore evidently, looked upon as the main front, was likewise intended by its designer in England as the "architectural front" (chief facade) of the building. It may well have been his intention for this elevation of the building to face westward toward the Wren Building and this is particularly likely to have been the case if the Wren Building and the Capitol were the work of the same architect, i.e., Sir Christopher Wren (p. 2), for the latter would surely have considered carefully the relationship of his two structures. Otherwise, one may ask if the fronts of the two buildings were not intended to face each other, why should the two have been placed at either end of this major Duke of Gloucester Street axis? The form of the building, i.e. , two equal wings joined by an open arcade, was, furthermore, such that 36 had the so-called architectural front been placed toward the west, it would have permitted the main street, in effect, to continue through to Waller Street without interruption, as we know from Theodorick Bland's survey map (p. 3) it was intended to.* Finally it would have made the approach to the building from York Road, at that time by afar the most heavily-trafficked route entering Williamsburg, most convenient.

REASON ADVANCED TO EXPLAIN ORIENTATION OF CAPITOL, VIZ., THE WISH TO GIVE MAIN MEETING ROOMS THE MAXIMUM SUNLIGHT

The builders of the Capitol, then, muSt have had some weighty reason for sacrificing these various advantages in turning the intended architectural front of the building toward the north where the ground fell off, making the approach from that direction much less feasible than from the other three, and causing what is obviously a side of the structure to face the main street. The theory proposed to explain this is based upon the circumstance that it was originally decided for reasons of fire prevention, to omit from the building the only means of heating then available, fireplaces, and this omission would have made the building cold and uncomfortable 37 in winter. In order to compensate as much as possible for this lack of heating, the rooms of chief importance, which were located in the curved ends of the wings, were turned south to give them the maximum benefit from the sun's heat. Any other orientation of the rounded ends would have cast one or the other of the two wings in shadow and thus deprived it of this warmth.

BUILDERS IGNORED DUKE OF GLOUCESTER STREET, IN TURNING SIDE OF CAPITOL TOWARD IT, BECAUSE IT WAS THEN AN UNIMPORTANT ROADWAY; CONSEQUENCE OF THIS LACK OF FORESIGHT

To the above explanation should be added, in partial justification of the turning of a side rather than the front of the building toward the Duke of Gloucester Street, the consideration that that particular avenue, regardless of the major role the planners of the town quite evidently envisioned for it, was, at the time the first Capitol was built, a very unimportant roadway. Apparently, those in charge of the building of the structure could not foresee the significance that this would take on when, in time, the intention inherent in the city plan would come to be fulfilled. Because of this irremediable decision to face the Capitol away from the prospective main street, a later generation recognizing the anomaly in the fact that a side rather than the front of the building faced the, by that time, major approach, was forced, by way of amending this situation somewhat in the structure rebuilt after the fire of 1747, to apply a two-tiered portico to the west facade and to designate the doorway in it as the main entrance to the building.

RELATIONSHIPS OF CENTERS OF CERTAIN ESSENTIAL BUILDING ELEMENTS HAD TO BE DETERMINED BEFORE EAST AND WEST FACADES COULD BE DESIGNED

Another question which was given careful study before the actual restoration of the building was begun had to do with the relation of the east-west axis through the center of the cupola to the center line of the west doorway and the center line of a 38 semi-circular foundation discovered adjacent to the west wall beneath the doorway and the relation of all of these to the axis of Duke of Gloucester Street. The establishment of these relationships was of essential importance in the determination of the number and spacing of the openings in the east and west walls, since neither the legislative acts directing the building of the first Capitol nor any other available documents gave this information.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL REMAINS TO BE DISCUSSED HERE BRIEFLY BECAUSE FOUNDATIONS HAD BEARING ON DESIGN OF SIDE FACADES

It would be well, before exploring the subject touched upon above to say a few words about the archaeological remains which were uncovered on the Capitol site, since these were involved in the decisions which were made respecting the form of the two side facades. 'The discussion of these will be brief since the archaeological drawing on p. 41 and photograph on p. 42 show and explain pretty completely what was found on the site.

ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY OF CAPITOL CAN BE READ IN FOUNDATION REMAINS

Much of the architectural history of the Capitol can be read in the foundation remains. The extent and plan character of the first and second buildings are clearly evident from the archaeological drawing, which is to say that the layout of the original structure and the modifications made in this building when it was rebuilt after the fire of 1747 are discernible.

SEMI-CIRCULAR FOUNDATION, WHEN UNCOVERED, APPEARED TO HAVE BRICKWORK OF TWO PERIODS

The archaeological feature which concerns us most at the moment, since it played an important part in the investigations into the nature of the west facade, is the semi-circular foundation adjacent to the foundation of the west wall. This foundation, like those of the main walls, had previously, for its preservation, been capped with concrete by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (A.P.V.A.) which owned the Capitol site at the time, 39 When the concrete cap of the semi-circular foundation was removed and the brickwork beneath it studied the latter was found to contain, at different levels, bricks which were believed to be of both the first and second periods, laid up for the most part with an oyster shell mortar containing more sand than that in the foundation walls of the original building. Little or no evidence was found of the bonding of the semi-circular foundation with the brickwork of the west wall.

COMMITTEE OF A.P.V.A. BELIEVED SEMI-CIRCULAR FOUNDATION TO BE THAT OF ORIGINAL WEST PORCH

The actual period of the brickwork of the semi-circular foundation was so difficult to determine with certainty that two quite different conclusions were reached concerning it. The members of the A.P.V.A. Capitol Committee (see Appendix for a listing of the membership of this) were of the opinion that the foundation was that of the semi-circular porch specified in the building act of 1699 (see Appendix). Had this view been accepted the eventual appearance of the reconstructed Capitol would have been considerably different from what it is, since the center line of the semi-circular foundation virtually coincides with the east-west center line of the cupola and, of course, the west entrance would have been on this center line.

ARCHITECTS DECIDED THAT ORIGINAL PORCH AND DOORWAY HAD BEEN MOVED AND THAT POSITION OF SEMI-CIRCULAR FOUNDATION WAS THAT OF SECOND PORCH

The lack of evidence of the bonding in of the brickwork of the semi-circular foundation with that of the main west wall, the heterogenous character of the brick work of the foundation and also, evidence of the disturbance, at some time in the past, of the brickwork of the west wall of the building convinced the architects that this was not the foundation of the original west entrance porch. They decided that the original doorway had been farther north and 40 had lined up with the first position which had been fixed for the cupola but never carried into execution {see plan I of Diagram A, p. 46. This had been closed up at some time before 1747 and a new doorway and porch had been built to line up with the position of the cupola as actually built. The semi-circular foundation, they maintained, was that of this altered entrance porch. The fact that no foundations of the original porch were discovered was not remarkable, they argued, since, in accordance with a stipulation in the act of 1701 {see Appendix) the first semi-circular porch had been supported on cedar columns and these would long since have disintegrated. The reasoning of the architects prevailed and, since the structure was to be restored to its original condition, the semi-circular foundation was ignored and the doorway was placed some 6'-9 ½" north of the center line of the semi-circular foundation, in the position which it had taken in consequence of its having been made to line up with the cupola as first planned.

RECTANGULAR FOUNDATION ADJACENT TO WEST WALL AS THAT OF TWO-STORY PORCH OF SECOND CAPITOL

In concluding this brief treatment of the Capitol foundations, the attention of the reader should be called to the large rectangular foundation which is seen, in the archaeological plan, p. 41 and in the photograph, p. 42, to abut the west wall. This, without question, was the foundation wall of the two-tiered west porch of the second building, both because it corresponded in size and shape with this porch and because its brickwork was similar to that of the foundation walls of the squared-off south ends which we know belonged to the second building.

41ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF CAPITOL [Image unavailable - Oversized]

42 OLD CAPITOL FOUNDATIONS, LOOKING SOUTHEAST

OLD CAPITOL FOUNDATIONS, LOOKING SOUTHEAST

WITH ENTRANCE CENTER LINE DETERMINED, WINDOW SIZED AND SPACING COULD BE WORKED OUT WITH AID OF BODLEIAN PLATE DRAWING OF NORTH FACADE

Once the architects and the A.P.V.A. building committee had come to agreement on the location of the west doorway they had the key to the positions of the window openings in the west facade, as well as in the identical east facade. They assumed, on the basis of the prevailing architectural usage of that day and this, that the window sizes, types and spacing would have been the same on the east and west facades as on the north, the windows of which were clearly indicated on the Bodleian plate drawing. (See p. 30). These sizes and types (round-arched below and straight-headed above) and the spacing when applied to the east and west facades, resulted in a relationship of openings to wall in those facades which was architecturally correct and satisfying. This was strong presumptive evidence that these window sizes and types and their spacing were a close approximation of the original window condition and, consequently, the architects developed the straight facades of the building on this basis. In doing this, they used, of course, the plan and elevation dimensions fixed by the original building act of 1699 (see Appendix) and confirmed by the foundations and, preserving a constant distance from the centers of the end windows in any facade to their adjacent building corners, they found that a difference in the center-to-center spacing of the openings in the east and west facades and those of the north ends of only 11" resulted. Since there is no possibility of a direct and close comparison, because the facades stand at right angles to each other, this difference is insufficient to become apparent to the eye, so that these adjacent facades seem to the observer to be harmoniously related to each other.

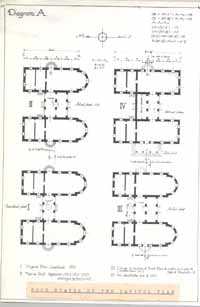

44A. H. HEPBURN'S CAPITOL NOTES; FOUR DIAGRAMS ACCOMPANYING THESE ARE INCLUDED IN THIS REPORT

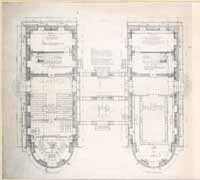

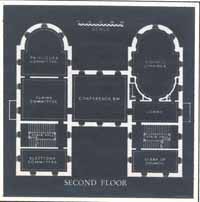

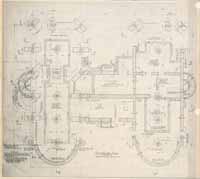

In order to explain the major problems encountered by the architects in the reconstruction of the Capitol and the conclusions they reached concerning them, Andrew H. Hepburn of the firm in charge of the work compiled an informative paper entitled Capitol Notes, copies of which are available in the Architectural Records Office. This paper should be consulted by those desiring additional data on the matters which have been discussed in present chapter of this report. Mr. Hepburn supplements his commentary on the reconstruction of the Capitol with several diagrams which show, in plan and elevation, the various eighteenth-century states of the building. We are including, on the four succeeding illustration pages, reproductions of these very helpful drawings. These will be found to consist (in the order in which they appear here) of the following:

- Diagram A: Four plans of the building showing the Capitol, I, as originally planned, but not executed; II, as originally executed; III, as altered, by moving the west doorway southward to line up with the cupola and IV, as rebuilt after the fire of 1747.

- Diagram C: The west elevation as it was originally built and as it was reconstructed.

- Diagram D: The west elevation following the moving of the doorway and the inclusion of an additional window in both the first and second stories.

- Diagram E: The west elevation of the building as rebuilt after the fire of 1747.

TWO ITEMS ON DIAGRAM A SEEM TO BE OF DOUBTFUL ACCURACY

Attention should be called to two items shown on Diagram A concerning the accuracy of which the author believes there is considerable doubt. On plan III is the note, "Arches closed 1720." These arches were probably never closed in the first building, as has been pointed out on p. 31. Secondly, on plan IV, the same arches are indicated as closed on the north side by masonry and the corresponding arches on the south side are shown open. From descriptions of the condition of the one-time "piazza" which have been left by contemporary travellers who saw it and from the drawing made of it by Benjamin Latrobe, it seems likely that the arches of two sides of either one-half of the space, or the whole of it, were enclosed in the second building and that the enclosure was effected by placing doors in the archways, not by bricking them up (pp. 32-34).

DIAGRAMS SHOWING DIFFERENT STATES OF PLAN AND WEST ELEVATION OF CAPITOL

46 DIAGRAM A

DIAGRAM AFOUR STATES OF THE CAPITOL PLAN 47

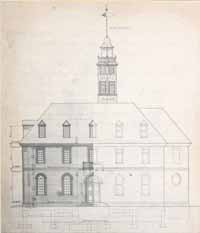

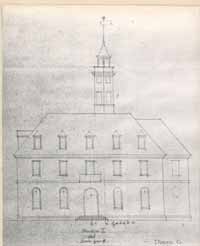

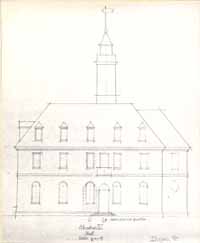

CONJECTURAL DIAGRAM OF WEST ELEVATION OF THE CAPITOL SHOWING THE POSITION OF THE OPENINGS IN THAT FACADE WHEN THE BUILDING WAS ORIGINALLY BUILT. THE CUPOLA, RISING FROM THE RIDGE OF THE ROOF OF THE "PIAZZA" OR ARCADE LINKING THE TWO WINGS, WAS ORIGINALLY INTENDED TO LINE UP WITH THE EAST AND WEST DOORWAYS. BEFORE CONSTRUCTION OF THE BUILDING GOT UNDER WAY, HOWEVER, THE WIDTH OF THE ARCADE WAS DOUBLED WITHOUT ALTERING THE POSITION OF ITS NORTH SIDE, WITH THE RESULT THAT THE ROOF RIDGE AND THE TOWER ASTRIDE IT MOVED SOUTHWARD AND LEFT THE AXIS OF THE TWO ENTRANCES. THIS IS THE CONDITION SHOWN IN THE ABOVE DIAGRAM. FOR THE SEVERAL CONJECTURAL STATES OF THE CAPITOL PLAN, SEE DIAGRAM A.

48

CONJECTURAL DIAGRAM OF WEST ELEVATION OF THE CAPITOL SHOWING THE POSITION OF THE OPENINGS IN THAT FACADE WHEN THE BUILDING WAS ORIGINALLY BUILT. THE CUPOLA, RISING FROM THE RIDGE OF THE ROOF OF THE "PIAZZA" OR ARCADE LINKING THE TWO WINGS, WAS ORIGINALLY INTENDED TO LINE UP WITH THE EAST AND WEST DOORWAYS. BEFORE CONSTRUCTION OF THE BUILDING GOT UNDER WAY, HOWEVER, THE WIDTH OF THE ARCADE WAS DOUBLED WITHOUT ALTERING THE POSITION OF ITS NORTH SIDE, WITH THE RESULT THAT THE ROOF RIDGE AND THE TOWER ASTRIDE IT MOVED SOUTHWARD AND LEFT THE AXIS OF THE TWO ENTRANCES. THIS IS THE CONDITION SHOWN IN THE ABOVE DIAGRAM. FOR THE SEVERAL CONJECTURAL STATES OF THE CAPITOL PLAN, SEE DIAGRAM A.

48