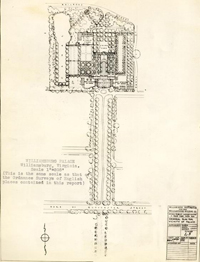

A COMPARISON OF THE WILLIAMSBURG PALACE GROUNDS LAYOUT WITH THE LAYOUTS OF ENGLISH PLACES OF THE SAME GENERAL TYPE AND PERIOD ALSO NOTES REGARDING THE DETAILS OF THE ABOVE COMPARISON AND NOTES ON ENGLISH COTTAGE GROUNDS. COMMENTS ON THE PLAN OF THE TOWN OF WILLIAMSBURG.

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0034

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

A COMPARISON OF THE

WILLIAMSBURG PALACE GROUNDS LAYOUT

WITH THE LAYOUTS OF ENGLISH PLACES

OF THE SAME GENERAL TYPE AND PERIOD ALSO

NOTES REGARDING THE DETAILS OF THE

ABOVE COMPARISON AND NOTES ON

ENGLISH COTTAGE GROUNDS.

COMMENTS ON THE PLAN OF THE TOWN OF WILLIAMSBURG.

REPORT TO MESSRS. PERRY, SHAW & HEPBURN, ARCHITECTS,

BY

ARTHUR A. SHURCLIFF

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT —

BOSTON

-

SEPTEMBER 1, 1932

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT

11 BEACON STREET, BOSTON, MASS. August 29, 1932.

REPORT ON ENGLISH TRIP

Perry, Shaw & Hepburn,

141 Milk Street.

Boston, Massachusetts.

Dear Sirs:

Below is as condensed a report on my recent (July 22nd to August 29th) trip to England as I can devise to show the many English facts which relate to our Williamsburg facts and needs.

A COMPARISON

As you see, the report takes our Williamsburg findings and plans for the Palace grounds and compares them with the "earmarks" of the series of typical English "place" periods and styles which may have influenced Virginia Governors and their coworkers in laying out the Palace grounds. Evidently these men would have been influenced also by the traditions which had developed and had been used in Virginia itself up to that time.

Evidently the most important facts of design for the Palace grounds are the actual findings revealed by the Palace excavations, Palace documents. Virginia characteristics and the known available kinds of trees and other plants used in Virginia at the colonial period. These facts are sometimes incomplete or are not in apparent agreement with one another. Therefore we must seek facts next in order of dependability. These facts are found (we assume) in the English layouts of the period when the closest ties of Virginia were with England. The British Governor, representing the Crown, probably would have been under the away of English traditions and the prevailing fashions when he took a strong hand (as Spotswood did) in constructing the Palace grounds at Williamsburg.

SPOTSWOOD

We have looked up Spotswood's history and find he was widely traveled for his day (see my letter to Harold Shurtleff; also see his findings). He knew little, however, of his ancestral home in Scotland (see plan page 209). Whether his cosmopolitan experience did or did not influence his taste in gardens we do not know, but the remains of the Williamsburg Palace grounds as we find them show a very pronounced English character.

CONFIRMATIONS

Incidentally, it was thought that the trip might yield interesting but not necessarily useful English confirmations of our known and dependable Virginia facts. All of us have been to England many times and our common knowledge has been of aid since the work began. I have made four previous trips to England and the continent. As you know, the present trip was devoted intensively to the study of technical details which have arisen during the past year or two of the Williamsburg plans.

I do not attempt to review the vast amount of authentic data which you have collected previously through Mr. Harold Shurtleff's researches, but I assume everyone who reads this report is familiar with his basic and highly detailed findings all of which have guided me. It is also plain that I have made no discoveries in England. I have merely gathered well known facts and have placed them for comparison with other facts.

Having conferred with you regarding this report I will follow your suggestion and restudy the Palace plan in the light of the report so we can all size up the restudy.

Yours very truly,

ARTHUR A. SHURCLIFF.

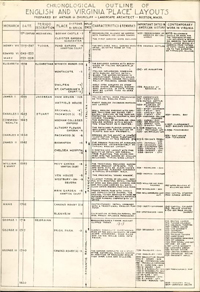

CHRONOLOGICAL OUTLINE OF ENGLISH AND VIRGINIA "PLACE" LAYOUTS PREPARED BY ARTHUR-A-SHURCLIFF — LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT — BOSTON, MASS.

CHRONOLOGICAL OUTLINE OF ENGLISH AND VIRGINIA "PLACE" LAYOUTS PREPARED BY ARTHUR-A-SHURCLIFF — LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT — BOSTON, MASS.

A LIST OF ENGLISH PERIODS WITH THE SOVEREIGNS, VIRGINIA GOVERNORS, DATES. ENGLISH AND VIRGINIA EXAMPLES AND NAMES OF AMERICANS KNOWN IN VIRGINIA AT THE CORRESPONDING PERIODS

I have compiled the above list (see photostat on opposite page) using the layout of the places Sidney and I visited, measured, and photographed in England and America. I had the aid of Mr. G. A. Jellicoe, a teacher of English design and the author of a book on English, French, and German place planning. He was referred to me through the American Embassy (Colonel Woods opened the door) and through Mr. H. A. Tipping who is a long time student of English places and for years was the Editor of "English Country Life". The British Garden Club and the English-Speaking Union helped us to secure permission to see places which were closed to the public. Your lists of places were useful also.

PARALLELISM OF PERIODS OF DESIGN IS

50 TO 75 YEARS LATER IN AMERICA THAN IN ENGLAND

The formal (symmetrical, rectangular) layout of English places came to an end in England between 1725 and 1750 according to Mr. H. A. Tipping. Fashion turned then to picturesque (naturalistic) layouts of "Capability" Brown, Kemp, Kent, and later of Repton. This new fashion did not show itself in America until 1800 or thereabouts, and not to a wide extent until 1840 (see the design of Castle Hill, Virginia 1840). The extreme rigidity and aridity (as at Blenheim) of the French influence hurried English opinion to seek relief in the new naturalistic type of layout. French influence (see the "earmarks" of French influence page 11) did not reach America soon enough or strongly enough to make an impression in the formal layout styles in America until the naturalistic influence came here.

In other words, Williamsburg belongs to the formal period of place design.

GREAT VS. MEDIUM-SIZED PLACES

Although the small or medium-sized places are most in scale with the Palace, some of the large places (Hampton Court, Hatfield House, Wilton) showed useful points as noted below. In general, however, as I had previously visited many of the large places, we omitted them.

FRENCH AND ITALIAN INFLUENCE EARMARKS

At Williamsburg we do not find the following French earmarks which crept into the English work later:

- 1Diagonal vistas.

- 2Long canals on vista lines.

- 3Round Points or half circle "Points".

- 4Bosquet.

- 5Wall fountains and Chateau d'eau.

- 6Grottos and gazeboes (detached).

- 7Geometric water basins and pools.

- 8Water jets and fountains.

- 9Much statuary.

- 10Niched walls of foliage.

- 11Important architectural ramps.

- 12Grand staircases.

- 13Elaborate high masonry retaining walls.

- 14Parterres.

- 15Elaborate architectural lattice and trellises.

- 16Palladian and other architectural bridges.

- 17Curving terraces with or without walls.

- 18Architecture of these influences.

DUTCH INFLUENCE

At Williamsburg this influence in the layout of the Palace grounds is apparently absent.

Long, low, no change in levels, long canals, long rows of Poplar trees, curious shapes of clipped trees, garden houses (tools in basements), set to overlook the street as well as garden and canal, for example at Westbury.

EARMARKS OF THE NATURALISTIC SCHOOL

CHAMPIONED BY KEMP, "CAPABILITY" BROWN, REPTON,

BEING A SCHOOL LATER IN PERIOD THAN THE WILLIAMSBURG PALACE

We do not find this influence in the Palace records and findings. We know, however, that this School influenced Mount Vernon, Wye House, and other Southern places.

- 1Ha-ha walls.

- 2Clumps of trees placed irregularly.

- 3Separate trees placed irregularly.

- 4Shrubbery ditto #2 and 3.

- 5Flowers ditto #2 and 3.

- 6Irregular pools or ponds and waterfalls.

- 7Winding brooks, rivers, waterfalls.

- 8Artificial hills and hollows made to look "natural".

- 9Artificial ruins.

- 10Artificial dead trees.

- 11Ogee slopes instead of straight terrace slopes.

- 12Scattered statues, bridges, "cottages".

| EARMARKS OF ENGLISH PLACES | EARMARKS OF THE WILLIAMSBURG PLACE GROUNDS | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | The buildings are of English design. | Our buildings show English influence. |

| 2. | Long axial approach to the front door with two, four, or six rows of trees. See page 29 for comment on location of road ways. | Same at Williamsburg. Our inner tree rows are 100 feet apart which is very wide in England. |

| 3. | Outer and of this approach is provided with gates of wood or iron. | Think we ought to dig for gate foundations opposite the Bruton Parish - Neale line. |

| 4. | Inner end of this approach is received through enclosing walls or fences through which vehicles usually penetrate. | Same at Williamsburg, but apparently vehicles did not penetrate the forecourt. |

| 5. | Symmetrical for court. | Same at Williamsburg. |

| 6. | Definite lateral service entrance with gates through walls. | Same at Williamsburg but there are two such lateral entrances one of which was perhaps not wholly for service purposes. |

| 7. | Service buildings gathered but not usually composed symmetrically | Same at Williamsburg. |

| 8. | Stable with courtyard usually walled. | Assumed to be the same at Williamsburg but walls have not been found |

| 9. | Walled or hedged combined vegetable and fruit garden having no axial relation to the house as at Wilton, Claremont, Althorp. Straight paths of gravel. Fruit trees (in rows) headed back. Fruit trees trained on walls. Greenhouse and tool house. Flowers sometimes grown among vegetables. | Same proposed for Williamsburg but no greenhouse. |

| 19 | ||

| 10. | Approach axis continued on opposite side of house and symmetrically arranged. | Same at Williamsburg. |

| 11. | Transverse axes of house sometimes developed with symmetrical treatments when there are transverse masters' doors. | There are no masters' doors of this kind at Williamsburg, therefore no transverse axis has been found or planned. |

| 12. | Axes sometimes developed parallel with and near the west, north, or east facades of the house (I will call this a tangent axis). | Marked tangent axis found at Williamsburg and embodied in all our construction work. |

| 13. | Right angular corner areas between the cardinal axes developed either without relation to one another and often not developed at all. | This is the case at Williamsburg according to our findings and our plans. |

| 14. | Absence of naturalistic grading, planting, paths, roads, gardens, water surfaces, or other naturalistic features. | Our Williamsburg findings reveal no naturalistic features and we have shown none except beyond the canal and beyond the ice house where the wild countryside is assumed to have existed. |

| 15. | "Mounts" are found and vary from four or five to eight or twenty-five feet in height, sometimes square, or round, or linear. Usually at corners or along sides of compositions, though sometimes (Packwood House and New College) on transverse axis. | We have proposed a Mount at Williamsburg which I am working on. Mr. Rockefeller remarked that the mound over the ice house is a Mount as we have planned it. |

| 16. | Flower garden is sometimes found. | We have one at Williamsburg. The design is curiously like the old "Physic Garden" at Oxford, in the quadriparti pattern and in the lack of symmetry in one direction. See page 27. |

| 21 | ||

| 17. | Graveyard is usually at the nearest chapel (sometimes private) or church. | We have one at nearby Bruton. The one in the flower garden zone is of course not pertinent to the design but is justified by Virginia custom. |

| 18. | "Raised terraces" from 9 inches to 3 feet high are found usually across the end of an axis (as at Brickwall and Ven House) or around a central composition (as at Brickwall) or on each side of a main vista (as at Hatfield House). | If these had existed at Williamsburg they would have been lost by the known long-time ploughing of the ground after 1800. I suggest that we build three: one 9 inches high on each side of the main axis against the brick walls and one 18 inches high at the end of the shooting range. |

| 19. | Pleached arbors are found, either flanking an axis (Chiswick House, and Hampton Court) or surrounding a garden on three or four sides (Matfield House, and Kensington Palace Garden). | I suggest one on each side of the main axis on the raised terraces suggested above at Williamsburg. |

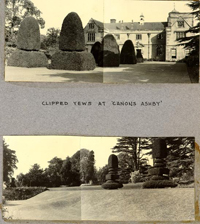

| 20. | Shallow terraces are found constantly even though not actually needed to take up the slope of flattish ground. (See Canons Ashby). All terraces are straight. | At Williamsburg note the stable yard terrace along south edge. |

| 21. | Rectangular "canals" of water (Westbury on Severn, Hampton Court, Knole Park) with terraces on edges where needed, also with weeds and flowers in the water which sometimes goes dry. | Same at Williamsburg, but our has an interesting enlargement at one end. Think we should omit proposed bridge as I find no precedent for one. We expect weeds, flowers, and authentic droughts. |

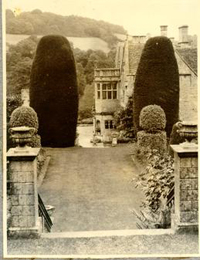

| 22. | Rows of large clipped evergreen trees (Owlpen, Canons Ashby, Hampton Court, Packwood, Cleeve Prior Manor, Brickwall, Montacute, and others). | I think we need these. See subsequent notes regarding available trees for purpose. See pages 148-167. |

| 23 | ||

| 23. | Clipped evergreen hedges. | I think we ought to clip the Box hedges in the flower garden at Williamsburg. See page 55. |

| 24. | Long narrow flower beds backed up by walls or planting are sometimes found. | We have not shown any as yet and may not need them because we have a flower garden. |

| 25. | Clair-voyée - generally on main axis. wood or iron. | We have one at Williamsburg. Think it should be moved to the east property line. |

| 26. | Urns on pedestals (common in Queen Anne's time). | We are considering some at Williamsburg. |

| 27. | Sundials, horizontal (Hampton Court, Brickwall 1833, Canons Ashby). Sundials also used on the building walls vertically. | We are considering both. Mr. Jellicoe questions the placing of sundials on cardinal axes in old times. Thinks the dials were not a "feature" at first. |

| 28. | Orangery (Ven House, Montacute). Usually at the end of a tangent axis near the house. | We are not proposing one. |

| 29. | Ramp of earth (Knole Park, Canons Ashby). | At the Palace we have not found need for one but they would be used if we build the lateral raised terraces which I advocate above in No. 18. |

| 30. | Statuary sparsely used. | We do not propose any. |

| 31. | Courtyards, paved. | Ours are paved in whole or part. |

| 32. | Steps of stone. | We find them true to type of stone on the important main axis where brick (as on the steps to the Canal) probably seemed not formal enough. |

| 33. | Balustrades. | We have on certain walls. |

| 25 | ||

| 34. | Corner or parietal tea house, tool house, or other small building or privy. | We have at least two. |

| 35. | English kinds of trees, shrubbery and flowers. | We have many English kinds. We know the many kinds actually used. See our three volumes of trees, shrubbery and flowering plants. |

| 36. | A natural "Park" beyond the planned grounds. | We have the beginnings of one beyond the canal and ice house. |

| 37. | Gardener's cottage. | We have one. |

OLD "PHYSIC GARDEN" AT OXFORD

OLD "PHYSIC GARDEN" AT OXFORD

SYMMETRY OF THE EARLY GEORGIAN PERIOD

As we all know, there was a very interesting period of highly symmetrical "place" design which developed in England during the Georgian era. In some examples of this style symmetry was carried to extremes. An examination of the Georgian places illustrated in Britannia Illustrata shows that while symmetry on at least one axis and often on two axes was attempted in every case, it is only in about one-third of these cases that this attempted symmetry was carried out to the extent of needlessly duplicating service buildings or gardens. For further remarks on this subject refer to my letter to you of June 9th.

The remains of the Palace grounds in Williamsburg and the documents do not indicate that the extremes of this style determined the lateral position of the constructions. The topography did not lend itself to such lateral symmetry.

It is fair to assume that the men who laid out the Palace grounds and the gardeners who worked under these men, transplanted to America the kind of place layout which they saw constantly in their daily life and in their travels in England. These men must have visited many of the places I quote in this report. All these places show the influences of many centuries and the corresponding styles, from the oldest to the newest. I have noted the "earmarks" of the old English places and have compared them with the "earmarks" of our actual findings at Williamsburg. The tally is extraordinary in parallelism and justifies our belief that the symmetry of the layout was confined, as in the case of most of the Kip pictures, to the major axis of the layout and did not extend laterally into the secondary compositions.

WILLIAMSBURG PALACE GROUNDS EARMARKS

WHICH WOULD IMPRESS AN ENGLISHMAN VISITING THE CITY IN OUR DAY

An English visitor, after noting the resemblances of our Palace grounds to English types, would also note the following points of difference. Since these points are authentic of the Colonial Period according to our findings he could not be offended with them as mere wilful or mannered vagaries of a restoration. I think he would be enormously interested in them.

- 1The formal and intimate part of the approach avenue is a part of the street and lot plan of the town, and not a mere offshoot of it as in English examples.

- 2The entrance to this formal avenue is not fortified with gates. (As I have said elsewhere I think we ought to dig to see if we can find foundations of such gates).

- 3The inner rows of the avenue are very far apart (100 feet). He might wonder as I do, if there was not another pair of rows of trees inside these (perhaps the lindens we find mentioned) which would give more customary scale.

- 4The presence of private dwellings facing on the intimate part of the approach, the latter functioning as an open "green".

- 5The presence of front line fences nearly continuously on both sides of the approach.

- 6The absence of frontages of stonewalls or brick walls like those at Bruton Parish.

- 7The appearance of the many white painted wooden houses on each side of the approach.

- 8The use of Catalpa, Beech, Maple, and other trees along the approach avenue instead of English Elm or Linden as would be expected in England.

- 9The presence of a theatre and a publicly used bowling green on this approach.

- 10A forecourt which is not penetrated by vehicles.

- 11An exterior turnaround for vehicles.

- 12Two lateral service entrances symmetrically placed.

- 13An extraordinary number of small outbuildings each for a separate use.

- 14An architectural style interestingly different from those in England.

- 15An unusual protrusion or development of one of the Palace rear rooms (ballroom).

- 33

- 16Northerly outbuildings set at 45 degrees.

- 17Piers in brick walls set at same angle.

- 18Steps built of brick leading to canal.

- 19Canal unusually deep set with unusually high terraces and having unusual pond-like irregular extension.

- 20Unusual icehouse and mound.

- 21Unusual constriction of grounds at the north explainable at once by presence of modern railway line. The lateral compactness of the Palace grounds would seem expectable probably, owing to the presence of the two lateral house frontages.

- 22* The extraordinary use of a vehicular approach both at the front and rear, the latter on the garden axis, seemingly contrary to all English usage. I wonder if we are right in this, and am studying it.

- 23** The extraordinary intimacy of the stable yard with the gardens, and with no separating wall though walls apparently less needed are found elsewhere. Wonder if we are right about this, am studying it.

- 24Roughness of our lawns even at their best.

NOTE REGARDING GRAPE HOUSE

Since writing the bulk of this report, and while trying to decipher the curious remains of what we have thought to be the foundations of a stable, I suddenly saw that these remains perfectly fit the design of a lean-to grape house of the early kinds I have just seen in England. The relatively thin front retaining wall of low height, the thick (and high) rear wall, the central low-level paved walk, the interior marginal loam spaces, tally in position and in size with those grape houses. The long duct through the north wall corresponds exactly with the heating flue of those grape houses. The central enlargement of the foundations corresponds with the plan and elevation of the central pavilion (some times called "the palm house") of glass.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Though I have not reviewed my findings with you in detail and have not reviewed them with the restudy I am now making at your suggestion, I jot down the following recommendations based on the notes in this report. These will at least point out the items which I think should be studied.

- 1Dig east of Bruton Parish Church to see if there are gate foundations at entrance to Palace Green.

- 2Consider an additional inner double row of trees (lindens) in the Palace Green in case (when the Palace facade is exposed by the removal of the old school building) the two present rows (100 feet apart) seem too wide for pleasant appearance.

- 3Consider whether or not the "stable" was really a stable (we found only one wall and this a retaining wall) or a high garden wall of the kind used for English Vegetable gardens. This wall subsequently or in the beginning might have been provided with wooden penthouses for garden and pleasure use, as per the Frenchman's Map. The considerable cost of this massive retaining wall suggests an effort to secure alignment with the garden terraces, which alignment would have been very desirable for a garden-to-garden relationship but not for a stable-to-garden relationship. A stable so near the Palace, Palace gardens, Palace privies, seems questionable. The fact that a stable here would have cut across the whole garden scheme and would have (according to our present plan) created another vehicular approach at the north end of the Palace, thus duplicating the southerly vehicular approach in a very un-English manner seems questionable and takes away privacy in the gardens where the Englishman seeks privacy. The elaborate water-catching conduits which you unearthed would have been useful for gardening purposes. Animals could have been led to streams or ponds.

- 4Eliminate bridge at end of canal.

- 5Use clipped evergreen trees in the Central Garden district.

- 6Use two pleached arbors laterally placed in relation to Central Garden district.

- 7Use a raised earth terrace about 9-inches high, under each of these arbors.

- 8Use a raised terrace about 18" to 24" at north end of the shooting range in the 20 foot vacant space north of the tree box.

- 9Move clair-voyée east to the east line.

- 10Use a mount as discussed last June.

- 11Clip the dwarf box in the flower garden as described.

NOTES

41PLACES VISITED WHICH APPEAR IN KIP'S VIEWS, 1709

| NAME OF PLACE | LOCATION | CHANGES MADE SINCE KIP'S VIEW WAS MADE |

|---|---|---|

| Althorp | Northampton | Somewhat changed |

| Badminton | Gloucestershire | Much changed |

| Chiswick House | Middlesex | Not greatly changed |

| Hampton Court | Middlesex | Little changed |

| Knole | Kent | Somewhat changed |

| Newnham Paddox | Warwickshire | Completely changed |

CERTAIN PLACES WHICH APPEAR IN KIP'S VIEWS

BUT WHICH WERE NOT VISITED

| NAME OF PLACE | LOCATION | REASON NOT VISITED |

|---|---|---|

| Badminton | Derbyshire | Cannot be traced |

| Brightwell | Suffolk | No grounds |

| Burlington House | Middlesex | No grounds |

| Chelsea House | Middlesex | No grounds |

| Dawley | Middlesex | No grounds |

| Haughton | Nottinghamshire | Cannot be traced |

| New Park | Surrey | Cannot be traced |

| Orchard Portman | Somerset | Site of house only - No grounds |

| St. James' House Somerset House | London | No grounds |

| The Seat | Yorkshire | Cannot be traced |

| Windsor House | Berkshire | Cannot be traced |

| Longleat | Wiltshire | Completely changed |

| Eaton Hall | Cheshire | Seen on previous visit |

| Chatsworth | Derby | Too large to be comparable to Palace |

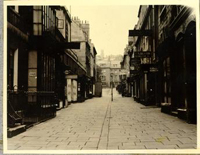

ENGLISH "PLACES" ON CROOKED STREETS

It is strange that the formal and symmetrical English places of the old days are found alongside winding lanes and crooked streets. Even in London there is no similarity between the layout of the grounds of the palaces and the lines of the nearby important thoroughfares.

WILLIAMSBURG "PLACES" ON STRAIGHT STREETS

It is equally strange that the Englishman, on crossing the ocean to Williamsburg, should have planned Williamsburg on straight lines which conform to the orientation and to the axes of the important "places" (Palace, College, Church, Capitol) and also to the modest halls, more modest cottages and the inns, all of which were laid out in a formal manner as at home in England.

Edenton, North Carolina, and many of the Southern towns and cities like Port Royal, Charleston, Savannah, were laid out with straight streets and with greens and squares. Further north in New Jersey and Pennsylvania we find Newcastle and Philadelphia laid out in a formal manner and with an eye to the good appearance of squares and public buildings. However, Williamsburg will always grip the attention of designers because it shows a larger grasp of the whole problem of the City and the placing of its public buildings, institutions, greens, and private places. The design was cleverly done on a ridge of somewhat difficult ground and the layout was placed coincident with the cardinal points of the compass. You know all this but I note it in connection with the following pages of notes.

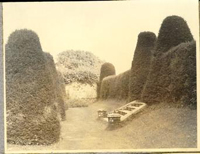

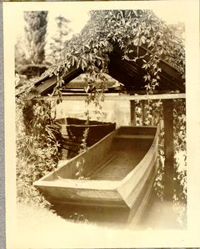

PUNT AT 'WESTBURY COURT'

PUNT AT 'WESTBURY COURT'

C.W. Neg. No. 77-DS-1450

THE PALACE CANAL

Again and again in England (Knole Park, Westbury, etc.,) there are canals with or without terraces like the one at the Williamsburg Palace. The proportions are long and narrow. The width is about the same. The Palace Canal is singular in having such high ground near it and consequently such high terraces. The irregular "horsepond" at the end is singular, and will add individual interest and beauty.

I think, however, we have no precedent for the bridge I proposed for the end of the canal and we should substitute a continuation of the gravel path system or a returned terrace.

In England canals are very shallow and abound in water plants and weeds.

BOATS IN CANALS

The punt or scow (see photograph) in the canal at Westbury is fifteen (15) feet long, twenty-two (22) inches wide at the end, with very high freeboard.

Boats or scows are generally present in the canals for use in clearing out weeds and for picking water lilies and other flowers.

WEEDS IN CANALS

The canals in the gardens, castles, and "Parks" are usually from 10 to 75% covered with lilies, sedges, weeds, or other plant growth. They are subject to drought. Have fish.

CURVING OR NATURALISTIC CANALS OR FISH PONDS

Not used in England until the Landscape School of Kemp began to destroy the old formal designs about 1700 to 1750, by which time in England the formal taste had passed. It did not pass for a half century or more in America.

At Knole Park, one of the old fish ponds shown on Kip's drawing has been filled wholly with earth and rubbish. The other has been reduced in size and our bed in the late Italian manner.

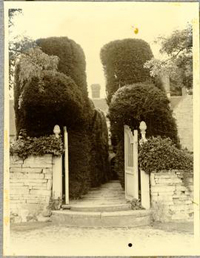

CLIPPED IRISH YEWS AT 'MONTACUTE'

CLIPPED IRISH YEWS AT 'MONTACUTE'

CLIPPED YEWS AT 'ST CATHERINE'S COURT'

CLIPPED YEWS AT 'ST CATHERINE'S COURT'

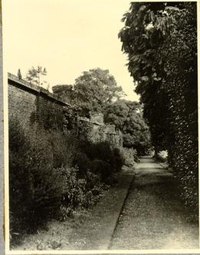

INTERIOR OF YEW HEDGE AT

INTERIOR OF YEW HEDGE AT

'WESTBURY COURT'

DANGER IN USE OF TOPIARY WORK

In localities of England where striking ancient topiary designs occur like eagles, peacocks, animals, soldiers, etc., these designs are copied by nearby modern teahouses, shops and hotels. The result is, of course, to cheapen the impression of the ancient work. To use other than the simplest geometric forms at the Williamsburg Palace would open us to the humiliation of seeing all the nearby road houses copy our designs and thus cheapen them.

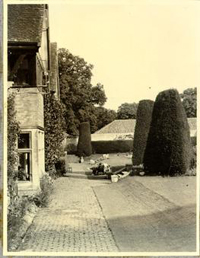

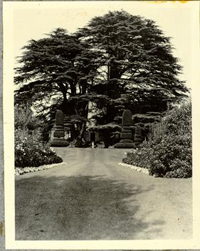

NATURAL ENGLISH YEW TREES

When free-growing, the English Yew is sprawling but not with the character of the great Cedar of Lebanon which was and is so widely used as a large natural-growing tree. This cedar grows so fast that it does not compete with the English Yew for hedge purposes because (like our White Pine) it soon gets out of hand. The two large free-growing Yew trees on the south side of Canons Ashby count as a single tree with two trunks. The clipping of the nearby English Yew trees has kept them from conflict with these free growing specimens. At Owlpen, the large free growing English Yew tree on the wall near the clipped English Yews (see photos) will soon need to be clipped or felled in order to protect the clipped neighbors.

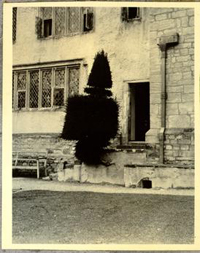

CLIPPED TREES AT WILLIAMSBURG

I suggest that we use clipped evergreen trees (Cedar or Holly) in the English manner in the space immediately north of the Ball Room and also along the sides of the Ball Room. This characteristic treatment will add to the interest, beauty, and I think to the authenticity of the grounds. Also, the plainness of the exterior of the Ball Room will be agreeably relieved.

The photograph on page 115 shows the use of clipped trees so closely against the walls of a building as to appear like buttresses of foliage.

THE UNIVERSAL CLIPPING OF GARDEN INTERIOR YEW HEDGES

English yew must be, and is, clipped when used in hedges in England. Otherwise because of its rather rapid growth and semi-scraggly habit, it would quickly smother or obliterate the garden design, the paths, and would destroy all nearby vegetation. Where formal or geometric clipping is not used (see photographs of Ayscoughfee) the Yew is nevertheless clipped to irregular rolling contours much like the effect produced by our Virginia tree box and dwarf box when allowed to grow naturally. The same applies to specimen garden English Yew trees.

The photograph page 50 shows the large trunks and leafless branches in the interior of very old hedges of English Yew.

54SHALL WE CLIP OUR PALACE BOX?

In England (for reasons which I will report on later when my investigations are complete) tree box and dwarf box are not very common. Because of its exceedingly slow growth (dwarf box) would not require clipping except at great age when the size might become an embarrassment, if the architectural effect of clipping were not sought. Not all Englishmen object to a billowy effect (see photographs 54 and 57), which show English Yew clipped to a wavy contour).

Tree box is usually used in England as an evergreen ornamental specimen tree, and is most often seen (during the recent tour) within or on the borders of the woods of a Park.

At the Williamsburg Palace I should say let the tree box retain its present form without clipping. Let the large box on the terraces above the Canal remain unclipped. I think, however, we should clip the box in the West Garden to give distinction from other Williamsburg gardens and to secure the sense of order and precision common to English garden designs. The fact that this box varies in size and ramps up and down need not bother us. At Medmenham Abbey I saw curving clipped ramps of this kind in English Yew. They made a very pleasant appearance but I did not have permission to take photographs. The curves were catenary in form, rising to flat-topped buttresses. Our dwarf box in the Palace flower garden already conforms approximately to these forms.

MOUNTS

These are characteristic of early English gardens. They were built to give elevated places from which the gardens could be seen to advantage, also when built near the edges of garden walls they gave views of other gardens or the outer world.

The mount at Knole is simply a pile of earth about 12 x 12 feet four to five feet high. It lies in the corner of the garden where two walls join at right angles. Two trees of large size (perhaps 75 to 100 years old) are growing on its upper edge. The whole surface, including the long gentle slopes (there are no steps) is covered with grass. It rises up to give a good view over the walls, but as these are high, they are locally lowered about 12" to 18" to assist the ease of outlook for persons sitting on the wooden bench. This bench is heavy but plain and is not fixed.

The old mount at Packwood (see plan, page 225) is a circular affair. The path which winds up cork-screw fashion is hidden in planting. This mount is at the end of the transverse garden axis and gives a pleasant view in all directions. There is only a small space (about 5' x 5') of standing room at the summit. I visited this.

The old mount *on the edge of the garden at Wadham College (I visited it) is about 150' long, six to seven feet high, about six to eight feet wide on top, perfectly straight, has a walk on top reached by modern stone steps, and clad in many trees and shrubs. The slopes are grassed and steep, about 1½:1. On the outer side, half the height is supported by a surcharged stone wall. The top of this mount is provided with chairs and tables and looks down on nearby gardens and low buildings.

The mount **at New College Oxford is pyramidal about 90 x 100 feet (paced measurements) and 25-30 feet high (rather carefully estimated by five-foot eye-levelling as I descended) sides very steep at least 1½:1. Completely covered and hidden by large trees and shrubbery. No paths or steps. Ascent forbidden by placards. Top is covered with trees and shrubbery and is flattish for space of about 8 feet by 10 feet. Top is about level with top of nearby city walls. Mount stands in center of a rectangular sunken garden (sunken about 4½ feet) and is on axis with main gate of College Quad. The volume of earth forming the mount might tally rather closely with the volume of the sinkage. This very large (clumsy) mount at New College makes the mound at Green Spring, Virginia, look like a veritable mount as I have contended.

PLEACHED ARBORS*

We found these arbors so often and of such considerable age in the authentic places, that they should be included among the "earmarks" of the English style of our period.

At Hampton Court, the pleached arbor is placed as shown on 1709 perspective, width 10 feet, trees are English Elms (Witch Elm variety) which lends itself to the severe pruning. These Elms vary from 12" to 16" in diameter and are set near together.- I counted 12 in 50 feet, or on an average 4 feet apart. The row nearest the rear wall (10' tall), 2½ feet from wall to center of trunk. Walk is gravel. Date is said to be Queen Anne.

The large (long) one following three sides of a square at Hatfield House is of Linden trees about 12" diameter in rows 10' wide and the trees 8 to 9 feet in the rows. Top is flat.

At Kensington Palace, London, the pleached arbor surrounds the pond garden on four sides. The trees lean in slightly. The temporary frame is intact but decaying. The width is twelve feet and head room about 10 feet.

Note the two compact rows of lime trees 18 feet apart which amount to pleached arbors and which flank the approach to Chiswick House.

RAISED TERRACES

These are characteristic of English places, and are "earmarks". They represent an attempt at terracing where the ground is too level to make terraces really necessary. These raised terraces either slope on all four edges or are banked up against walls as at Hatfield House where the raised terraces (they are only nine inches high) are free on two ends (steps here) and one long side about 30 feet wide and 120 feet long. Did not take photographs. See plan, page 213.

At Brickwall, the raised terrace forms a terminal at the end of the whole garden composition. Steps ascend it. See photos, page 71. Seat at each end. See also lateral raised terraces at Brickwall with lime trees near wall.

The great raised terraces at Hampton Court are well known and exist today as shown on Kip's perspective.

Note the raised terrace at the end of garden vista at Ven House is much like the one at Brickwall.

Similar raised terrace at Montacute House.

I suggest three raised terraces for the Williamsburg Palace grounds as noted elsewhere.

CLAIR-VOYÉES

The clair-voyée at Althorp House does not have an iron fence on top of the wall. Instead ditches are used on each side of the wall to keep men and animals from crossing it. See photo. Note very plain iron work for clair-voyée at Knole Park. Note absence of both wood and iron grills at the end of transverse axis at Montacute House.

In general the purpose of a "clear view arrangement" was to give a line of visibility where such a line would otherwise be cut off by high boundary hedges or boundary walls along the edges of the owned land or edges of cattle pastures or public roads. I did not find the clair-voyée used except on such boundaries, - never between gardens. I suggest therefore that we do not build the clair-voyée at the Williamsburg Palace as last proposed, between the two masters' areas, but move it east to the edge of the grounds. This more logical position will give us a longer vista, and will allow the outside world to catch a glimpse of the inner grounds at a place where such a glimpse will not hurt our privacy, and will doubtless increase the eagerness of visitors passing by to enter the grounds.

77

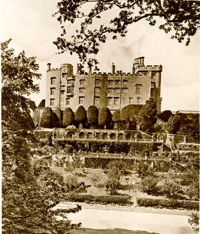

MONTACUTE HOUSE SHOWING RELATION OF APPROACH DRIVE TO HIGHWAY

MONTACUTE HOUSE SHOWING RELATION OF APPROACH DRIVE TO HIGHWAY

APPROACH AVENUES SOMETIMES EXTERIOR

At Wilton, Brickwall, Ham House, and many other places the great tree bordered avenues of approach are made exterior to the places as a whole and therefore to the forecourts by the presence of a public high way which outs across the avenue near the gates of the forecourt, and often makes the village intimate with this aspect of the mansion. This conforms exactly with the Williamsburg approach to the Palace in its relation both to Scotland Street, and the Duke of Gloucester Street if we assume that the visual approach begins at Francis Street.

APPROACH GATES SOMETIMES EXTERIOR

Either by design or because a public highway is a modern intrusion, important gates and gate houses sometimes stand at the distant ends of these exterior avenues and mark the formal entrance or the line of the property.

At Williamsburg if such gates had been built, they might have stood near the Duke of Gloucester Street end of the Palace Green where they would have been flanked by Bruton Parish Church on one side. I suggest that we dig in this neighborhood to see if there are indications of gate post foundations. Gates here would add perspective to the Palace and would express a relation of the Church to State and give distinction to Wythe House, Saunders-Dinwiddie and other places thus cloistered.

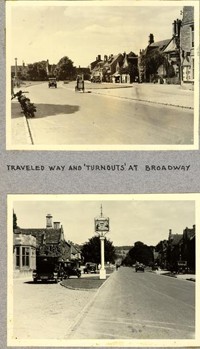

PALACE NORTH GATE AT RAILROAD STREET

The Williamsburg Palace gate on Railroad Street is fronted with a diagonal traveled way. This is exactly like the diagonal at the main entrance gate to Montacute House (see serial views), page 78.

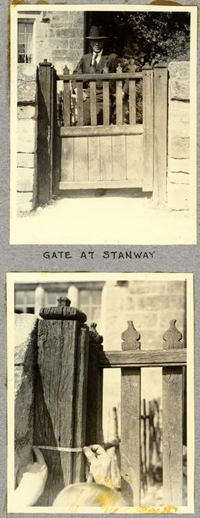

WOODEN ENTRANCE GATES OF DISTINCTION

At many places of a size equal to or larger than the Williamsburg Palace, interesting gates of wood rather than iron were used both for main approach and for decorative effect on minor axes. The very interesting ancient wooden gate of curious design at Canons Ashby has been saved in the ox shed near the chapel. It became decrepit with age and was replaced with the one shown in all the modern photographs. The photograph Sidney took of this old gate was spoiled. I am having a new one taken.

81

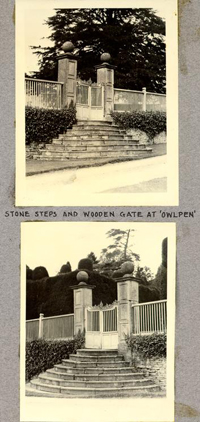

STONE STEPS AND WOODEN GATE AT 'OWLPEN'

STONE STEPS AND WOODEN GATE AT 'OWLPEN'

NARROWNESS OF APPROACH DRIVEWAYS

Many times we noticed the surprising narrowness of the private driveways which approach the great English places. These roads do not permit vehicles to pass without turning out on the grass. Eight, nine and ten feet are common. See photograph. All the Williamsburg traveled ways seem wide by comparison.

AXIAL DRIVEWAY USUALLY FOR MASTER

OR FOR GUESTS

Mr. Tipping of Country Life remarked that in England up to 1825 there were no good public or private roads because good methods of construction were not understood. The formal avenues of trees approaching the mansions were used by vehicles both exterior to and along the middle of the rows of trees. When one line of approach became too rough or muddy, other lines were used, but as a rule the central part of the mall was kept in the best order and was used only for important visitors and by the owner.

See also my note regarding the danger of falling dead branches on these avenues, page 87.

FALLING DEAD BRANCHES OF ENGLISH ELMS

We learned the extraordinary fact that many of the private driveways which at one time approached the great mansions through avenues of English Elm trees have been discontinued because of the sudden falling of great branches. The English Elm as it grows old becomes brittle and even in quiet weather will suddenly drop branches of dangerous size and weight.

NARROW TRAVELED WAYS

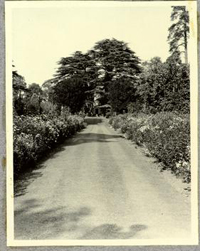

These prevail in all countryside roads of England where traffic is light. Hardly room for motors to pass, say 10 to 12 feet wide or less. Very crooked like Waltz Farm Road. Sides high and steep like latter but usually covered very densely with shrubbery, vines, and small trees. We should copy these slopes and vegetation where our Railroad Street passes through the new High School land. The vegetation is kept in check by bush scythes. Hedges (clipped once or twice a year) usually rise from the tops of the slopes and add to the apparent great depth of the road profile.

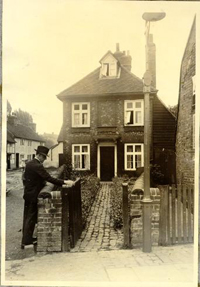

BRICK WALLS OF VIRGINIA TYPE IN ENGLAND

In and about Southampton, throughout Sussex in general, and notably at Amersham, we found brick walls both buttressed and plain which are like Virginia walls. The exact similarity was striking as shown in the accompanying photographs we took. See page 95.

VEGETABLE GARDENS USUALLY DETACHED AND WALLED

At the great places and the moderate sized places the vegetable gardens are separated from other gardens usually by brick walls ten to twelve feet high against which fruit trees are trained by fastenings of cords or withes of willow. The branches are usually 14 to 18 inches apart and horizontal. See photographs opposite.

Fruit trees are arranged in rows in most vegetable gardens and are severely cut back each season to one bud. Trees of fifty or more years old are often not over eight to ten feet high and are set 16 to 20 feet apart.

Flowers are often seen growing among the vegetables.

FLOWER "BORDERS"

Long, perfectly straight "borders" of flowers are seen in the old places usually backed up by high hedges or walls. These borders are often double being placed on each side of a path of grass or gravel six to twenty feet wide.

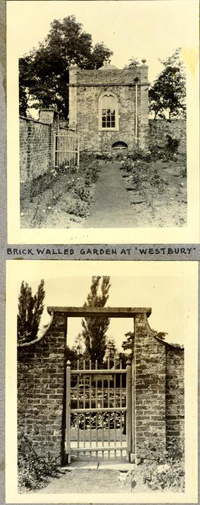

WALLED FLOWER GARDEN AT WESTBURY

This garden paces 45 x 87 feet, wall is 5' 10" high at south end. Wall cap of stone is 1½" thick at edge, 2" in middle, ¾" overhang with V-shaped drip. Gateway is 3' 6" wide.

BOWLING GREENS

| 42 yards, 126 feet square, but may be | 20 x 126 |

| 40 x 126 | |

| 60 x 126, etc. |

Ditch is 12" wide. Pebbles 1" to 2½" diameter.

Ditch is 2" below sod.

Ditch has wood on both edges.

Roll and cut across the rinks.

Mats 2 yards on green.

Jack 2 yards on green.

See photograph of ditch on page opposite.

BRICK WALL AND PATH AT AMERSHAM

BRICK WALL AND PATH AT AMERSHAM

BRICK WALLED GARDEN AT `WESTBURY'

BRICK WALLED GARDEN AT `WESTBURY'

BRICK WALL AND HOUSE AT AMERSHAM

BRICK WALL AND HOUSE AT AMERSHAM

SLOPING BRICK WALL AT AMERSHAM

SLOPING BRICK WALL AT AMERSHAM

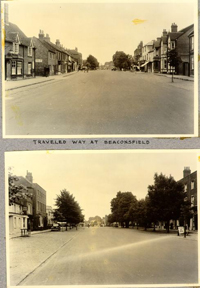

JOGGED SETBACKS

In towns of all sizes we found moderate setbacks of shops and houses. See plan of old Amersham, page 102 and photographs pages 98 and 103.

Fences, walls or hedges along the frontages are common as at Sulgrave.

These setbacks, whether fenced or not, recalled the setback of the Williamsburg stores, Montague, Governor Page, etc.

STREET TERRACES

Street border terraces with earth slopes, grassed (like those on edges of Francis Street, Williamsburg) are seen in many towns, see photograph page 174.

STREET WELLS

See photograph page 97.

STOCKS

See photograph page 132.

STREET WATERING TROUGH

See photograph, page 105.

SIDEWALKS AND TRAVELED WAYS

In the old times there were no sidewalks. Water ran along the midst of the muddy street. The edges of the streets needed to be the driest part. Sidewalks were built, subsequently, when wheeled vehicles came into use. The sidewalks were devised (as in the old Roman city of Pompeii) to keep water, mud and vehicles away from the houses and stores, approach to which by persons on foot, with pack horses, or on horseback, had not been too dangerous to limb or to structures before the vehicles came into use.

More recently these traveled ways have been smoothed, drained, crowned, and almost all of them are now bituminized.

BITUMINOUS ROAD SURFACES

The traveled ways of most of the country streets and even the byways of England have been bituminized as a measure of upkeep economy. In the cities this is true. Many of the old wooden block pavements of London are veneered with sand and bituminous material to reduce the slipperiness of the wood. I did not see any gravel-topped bituminous roads like the State roads near Williamsburg.

WALLS, STREETS, SIDEWALKS

Old Amersham: Many houses dated around 1650. Chiefly brick houses, some half timbered. Much use of Flemish bond with glazed headers like Williamsburg Paradise House, also with similar base and belt courses, also flat arches and coigns are of ground brick in many cases. Streets not straight. In middle part of town the street is widened by a jog of 20 to 30 feet recalling Williamsburg store district jogs. This jog takes place at Town House. See plan of this town, page 102, also see photograph 103. At Beaconsfield a similar relation of town houses to the main street occurs. Compare with Williamsburg's rectangular Greens in which the Court House and Powder Horn stand. Also compare with Greens at Edenton, North Carolina. There is no development of cross streets as at Williamsburg. Lot line and other low parapet walls (3' to 4' high) coped with moulded brick, some like Williamsburg. Profiles of walls do not follow geometric or architectural curves and thus recall old Virginia examples. Some of these walls were 6 to 8 feet high and buttressed like Virginia examples at Toddsbury and Green Plains.

Fences chiefly modern with wire fastenings. A few well built mortise and tenon fences. Few wooden picket fences. Great number of rear hedges enclosing vegetables or flower gardens, most of which are under intense cultivation. Note photograph on page 98 of jogged street fence like "Blair" at Williamsburg.

Sidewalks (except when of bituminous or cement material) of brick laid with broken joints, the stretchers running transversely. One exception photographed of broken fragments of brick laid with a border of whole brick, see page 107.

All curbstones of stone or cement.

At Beaconsfield the Town House is like Old Amersham in general position. Note the photographs showing the central bituminous road with gravel extensions of paved sidewalks. See page 113.

At High Wycombe the Town House is in street, see survey. Many interesting houses.

West Wycombe is almost equal in interest to Amersham. Often has overhanging second story the which we photographed. Photographed old sidewalk well surrounded by fence. See page 97.

Lane End is a small but moderately interesting village.

At Great Marlowe brick houses in monotonous but rather interesting blocks. Photographed tavern tables and benches out-of-doors. About three miles from town visited modern place "Wittington", a place of beauty but only 35 years old. A mile further was Medmenham Abbey. A lovely old house (once an abbey) on the Thames. Modern attractive garden with clipped Yew hedges.

NOTES ON STEEPNESS OF STEPS

We were told that the steepness of out-of-door steps shows the age of the layout. Anciently, steep steps as at Owlpen (see photograph page 116) were built and were acceptable. Later influence of the Italians brought a fashion for steps of gentle rise as at Montacute.

TAVERN TABLES ON STREET SIDEWALKS

Some Taverns (ordinaries) in the smaller towns have tables and benches in front of the building on the sidewalk, see photograph, page 116.

GROSVENOR SQUARE, LONDON (MENTIONED BY MR. CHORLEY)

See map London. Oblong with outer marginal path near fence. Wooded. Central raised mount 60 x 90 with steps (4 risers) on each of the four rectangular sides. Summer house about 10 x 16 in middle around base of old statue. Flower beds around edge of mount. I made a sketch plan not in this report.

11 GROSVENOR SQUARE, LONDON (MENTIONED BY MR. CHORLEY)

Garden of flagstone about 16 feet across central bare part. Bird bath in middle. Wooden lattices applied to party wall. Garden is built on roof of kitchen. All flower beds curbed with brick (2 courses) having a limestone cap about 4" x 8". Not an usual garden. This is the Kindersley Garden. I made a sketch plan not in this report.

CLAPBOARD FENCES

We saw a great many of these in Southern England. Though the clapboards are thin (oak), the frames to which they are nailed are very solid. See photographs. The clapboards are crenellated along the top line, but are sometimes capped with a strip 1½" thick (in middle) with ½" wash. Sometimes this strip is interrupted by the posts, and the latter have a thin cap about like the ones at the Lottie Garrett place.

The crenellated clapboard fence near Hatfield House is as follows:-

Clapboards of oak 3½ to 4" wide tapered from ½" to 3/16", lapped ½", nailed at each of 3 rails the latter triangular in section, mortised with 4 x 5 oak posts with two pins in each tenon, see pocket Kodak picture. Posts 9' on centers. Buttresses on each side of each post 20 to 24" tall. Near Pennshurst such clapboard fences are six feet high.

FENCE BUTTRESSES

It is interesting that the fence buttresses we found and photographed in Virginia at Windsor Castle, in Smithfield, are found in England. See photographs of above clapboard fence.

SUNDIAL AT HAMPTON COURT

The bronze is worn smooth in places by weathering and by the fingers which have touched it during two centuries. Diameter of the bronze is 20¾". See photographs page 128.

STOCKS AT EVESHAM

The height of the lower face of the plate of the stocks is 4 feet 7 inches. The seat of the stocks is acutely A-shaped about 1½" wide on top and bound with iron. The bottom of the A is about 4" wide. The seat is 5' long and about 18" high. Roof uprights are 5" x 4½". Beware of restored features of roof. See photographs page 132.

Hampton Court

Hampton Court

WE CANNOT USE KIP'S PICTURES AS A GUIDE FOR PLANTING

In looking over old "place" pictures, including Kip's views, we must not lose sight of the fact that the planting of today, unless it has been restored, cannot by any chance correspond to the old pictures. Take for example, Hampton Court. Kip shows little pointed trees on the east side of the Palace,- trees from 2 to 4 feet high intended to give piquant accent to the edges and corners of certain beds (see photostat, page 136). These trees have grown to a height of 20 feet or more and are no longer merely piquant. They spread right and left. See photograph, page 141. South of the mansion the elaborate garden spiked with little trees is now almost a continuous woodland of symmetrically placed large trees. If little trees were planted at the Williamsburg Palace 200 years ago (1730), these trees would be large now just as they are in England, see photographs pages 137, 141.

The question is, do we want to use little trees at the Williamsburg Palace gardens which trees will not be authentic in appearance today either in relation to Virginia or England or do we want to use large trees (cedars or arborvitaes which we can plant at small cost) which will give us the English "earmarks" of today and will look authentic in size today judged by Virginia conditions? I think we should use the large trees.

HOLLY TREES

These are common in private places and grow wild in the woods and hedge rows in England. At Hampton Court, variegated-leafed Hollies grow in large number in the Henry VIII Pond Garden and are often symmetrically placed. In London, Holly trees are found in the old Palace Parks, also in the many private "Squares" as, for example, Grosvenor Square. They are rarely clipped into geometric forms as is Yew, but holly hedges are always clipped. Easton Lodge, Warwick is said to have clipped holly specimens 50 feet tall. Mr. Jellicoe says 30-foot clipped holly trees are "not uncommon". I did not see any larger than 30 feet (diameter of foliage) on my travels.

HOLLY HEDGES

We saw these in almost every village, town, and in private places, large and small. They varied in height from four to twelve or more feet, and were clipped. We did not see Holly used in the gardens which were intimate with the frontages of the great mansions though they are used in the cottage gardens. In the great gardens, English Yew is almost universally used, being quick in growth, easily kept within bounds, good in color, and exceedingly small and smooth surface texture patterns.

We were told that Holly "makes a fine hedge but is slow coming to form". The English Holly is more glossy than ours, darker in leaf tone, but it has the same habit, thorny leaf, curly leaf, and red berries.

Large Holly hedge in village of Halestone, see photograph, page 144.

Holly hedges used very generally in the front part of Taplow Court (near Taplow) and at the entrance gates. Used extensively in the maze at Hampton Court with privet, hornbeam, and hawthorn. Used at the entrance to Wittington.

Variegated type of Holly used in Hampton Court "Pond Garden" and elsewhere in association with Yew.

Hedge of Holly 3 to 400 feet long (10 feet tall) along front edge of Hatfield House property near main approach road at times growing against a brick wall and overtopping it.

At Hatfield House many large Holly trees grow in the "Park" to a height of 40 to 60 feet.

See photograph, page 144 of the large Holly hedge at Chevening.

147ENGLISH YEW

This tree, which must not be confused with the erect Irish Yew, interests us at Williamsburg because:-

- 1In England it has been used for centuries for evergreen hedges of all sizes and shapes, for specimens cut to geometric form. Outside the gardens it grows to great size in its natural form which is a little like our hemlock. It is used almost universally in the old and beautiful gardens but in the gardens it is always clipped for reasons noted below.

- 2We know the Virginia Colonists tried to use English Yew but found it would not thrive in our climate. It is a fair assumption that in pursuit of the English traditions they used some other evergreen tree of similar habit which could be clipped. Of the evergreen trees available in Virginia (the cedar, holly, arborvitae, hemlock, pines) the cedar, the arborvitae or holly would have served the purpose and would have made immediate effects possible by moving in large trees from the fields.

- 3The decorative effect of clipped evergreen trees (yews) in the old English places is so marked, so characteristic, and so universal, that we ought, I think, to reproduce this effect in the Williamsburg Palace layout.

- 4In England, other than the English Yew tree has been used in the effort to get the effect produced by the clipped yew. At Althorp House the photograph we took shows the rows of Cypress viridis erecta 70 years old. At Montacute House the Irish Yew (A.D. 1830) has been used here and there in the same rows with the English Yew. Since the English themselves have cast about in England for substitutes for the English Yew to secure this characteristic color, form, and texture, I think we are not illogical in assuming that the Virginia Colonists cast about in the same manner and used cedar or holly.

- 5We have a record of the clipping of cedar in Virginia, as follows:-

Note: Record not on hand at time of going to press.

Jan. 11th, 1913.

Jan. 11th, 1913.

COUNTRY LIFE.

Copyright, GARDEN AT OWLPEN: FROM NORTH-WEST PROPERTY OF COUNTRY LIFE.

THE CLIPPING OF ENGLISH YEW TREES

The clipping of the English Yew trees, which stand in close formation today, became necessary for mechanical reasons to prevent the shading of the ground and the consequent, killing of grass within the shade. Also, the clipping prevented the upper branches of the tree from killing the lower branches near the ground by shading. Clipping also preserved sufficient space for walking between the tree rows.

At Cleeve Prior Manor, the trees for want of more radical clipping have shaded the inner surfaces of their own double row to such a degree that those surfaces have lost their foliage and show bare trunks and dead branches.

Briefly, the clipping we see at Owlpen, Brickwall, Canons Ashby, and in a host of other places where trees were closely arranged, must have been intended to save the trees from mutual destruction and those other destructive effects quite aside from an intention to make agreeable compositions of foliage masses. At Hampton Court we see the extensive clipping of the many east-side Yews to prevent them from killing the vegetation beneath them and to forestall the clogging of the great vistas. Doubtless the decorative effect resulting from the clipping was aimed at in all these instances but this aim certainly ran parallel to the mechanical necessity for clipping.

DISTANCE BETWEEN CLIPPED ENGLISH YEW TREES

The extraordinary close spacing of the Yew trees at Cleave Prior Manor is shown in the photograph. They were set so closely that the eventual meeting of the foliage of adjacent trees was a foregone conclusion. At Canons Ashby the `Yews, according to my measurements, are 18 feet apart on centers between rows and from 27 to 29 feet apart in the rows. The end trees are 39 feet from the wall of the house.

IRISH YEW NOT AUTHENTIC FOR WILLIAMSBURG

We learned of the Royal Botanic Society this tree was not known until a sport was discovered about 1780 and not generally planted in England for at least 30 years or so later. Therefore, it is not authentic for Williamsburg. We have been offered large specimens of this tree which have grown up in Virginia during the past 50 years. In England, the Irish Yew even when placed in close order, is not usually clipped because the erect and compact habit makes clipping unnecessary. Clipping is sometimes done as at Montacute House. The Irish Yew was seized upon by the English gardeners because it lent itself to a use rather better than the English Yew. The foliage is __________ and darker than the English Yew.

167

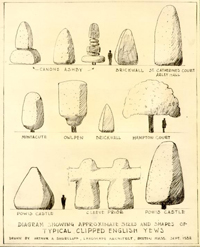

DIAGRAM SHOWING APPROXIMATE SIZES AND SHAPES OF

DIAGRAM SHOWING APPROXIMATE SIZES AND SHAPES OF

TYPICAL CLIPPED ENGLISH YEWS

DRAWN BY ARTHUR A. SHURCLIFF, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT, BOSTON MASS. SEPT. 1932

PLAN OF KNOTT GARDEN AT 'HAMPTON COURT'

PLAN OF KNOTT GARDEN AT 'HAMPTON COURT'

SHADE TREES NOT IN ENGLAND AS IN VIRGINIA

In England, trees for shade are not needed near houses. Trees make English houses and churches damp. The opposite is true in Virginia and makes a corresponding difference in the place layouts.

In England, the low winter sun and the corresponding short days of winter make shade trees undesirable near houses, schools, churches, on account of the increased darkness. The name is not true in Virginia and influences the place layouts correspondingly.

In England, since trees and arbors are placed where they can be visited from the house when the season is right for their enjoyment, or where they can be seen.

GARDEN KNOTS

Of late years, there have been feeble attempts in England to revive the ancient garden knots. You see then seriously attempted at Hampton Court in a spot where they are known not to have existed in old times. A scale plan (see photograph #170) is posted beside those at Hampton to add interest and to help visitors to see the knots despite the vagaries of the reluctant vegetation. These knots at Hampton Court are to be removed, first because they make such a messy appearance, and second because the site is not authentic. Mr. Lloyd has some knots in his garden. They are very weak looking and express the general fact that the authentic kinds of plants used to form the patterns do not lend themselves to the use, except with constant and costly clipping, tying, replanting, and other fussy, costly and annoying attention.

173STREET TREES

Street trees in the streets of English villages, towns, and cities, are generally few. The need to conserve sunlight in the windows, in the yards, and in the street itself, combined with the general cool temperature of the Island, make shade trees undesirable and unnecessary.

The photographs pages 103, 174, show the absence of street trees.

The light in England is so mellow and often so hazy, that the absence of street trees does not lend an appearance of rawness and garishness as would be the case in Virginia.

177TREES SEEN EVERYWHERE

These trees are seen on every hand as, for example, along the line of the Southern Railway, London to Southampton:- Oak, English Elm, Ash, Holly, Beech, White Birch, Jack Pine, Spruce, Wellingtonia, Austrian Pine, Scotch Pine, Red Pine, Hawthorn, Catalpa, Willow, all the fruit trees, Locust, Mountain Ash, Linden, Hornbeam, Yew (English), Yew (Irish), Horse chestnut, Monkey Puzzle, Larch, Sycamore, Maple, Lombardy Poplar, Carolina Poplar, White Poplar, Tulip Tree (scarce), American Elm (rare), Hickory (Walnut), Arborvitae.

OLD TREES NOT REPAIRED AT OLD PALACES

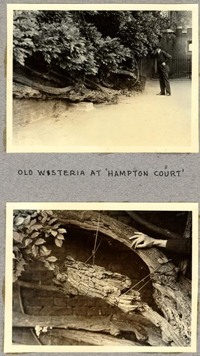

At Hampton Court the large holes and broken branch stubs of the ancient English Elm trees of Queen Anne's Bower are not repaired. Rotten wood shows on the edges of the holes but the latter have been cleared of rubbish so the light and air may enter. The nearby lawns and planting are maintained with absolute perfection. There is no indication of an attempt at economy of upkeep. Evidently, therefore, because of the absence of tree repair work there is an appreciation of the significance of hollow and decrepit trees in the historic picture. This appreciation is shown by the care used in supporting the weight of the large rotten trunk-like branches of the Wisteria vine. Without these supporting cords (see photograph) the old rotten branches would have fallen long ago. The label giving the name of this vine is attached near this rotten part as if to draw attention to the age as proven by the decrepitude and the bulk of the decay. None of the decayed wood or bark has been scraped or cleared off, or "treated".

At Hatfield House, the grounds of which are in a high state of upkeep, several large dead oak trees are allowed to stand in the "Park", evidently because they are thought to add to the good appearance of the landscape.

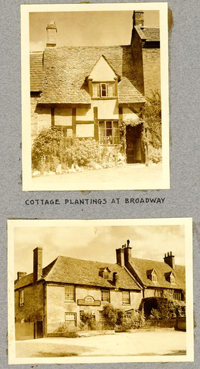

FLOWERS

The cottage grounds, front and rear, are full of flowers. There are flowering vines on the walls of the houses and on the walls on the street property lines. This is true of the home of the unsophisticated back country villager as well as that of the tenant in the better industrial towns. No encouragement or underwriting is needed to secure these flowering effects.

Window boxes are rare perhaps because flowers abound elsewhere, and there is no "fashion" for them.

DOVECOTES

Pigeons raise such havoc in the fields that dovecotes are not in favor. We saw some amazingly large stone dovecotes (20 x 20 x 35 feet high) containing thousands of stone pigeon holes. Operation of these great establishments for pigeons was forbidden by law a century or two ago owing to the depredations of the flocks of birds upon the gardens and fields of the common yeoman.

BIRD HOUSES

These are rare. Birds are not wanted. They do vast damage in the orchards, gardens and grain fields. Birds are trapped, but the farmers know this is not wholly a gain, since the birds destroy insects.

ENGLISH COTTAGE PLANTING

The roofs and walls of English cottages are generally (but not always) free of tall tree shade or dense vine foliage. The dampness of the climate makes such shade intolerable owing to the limited area of the lots, every inch is occupied by structures, paths, or planting. Little space is "wasted" on lawns unless the householder has unusual wealth. The wealthy householder is often more interested in flowers and in plant raising than he is in lawns. Flowers, vegetables, fruit trees, and shrubbery (often berry bushes) are planted in great profusion and are tended with the utmost interest by the householders who depend on the vegetables and fruit. Flowers, vegetables, and fruits are grown in the same beds. Paths are usually gravel and are straight. Garages and other outbuildings are few. The cool climate permits kitchen work, meat curing, milk keeping, etc., to be carried on in the main house.

STUNTING TREES BY CUTTING BACK

The Englishman is a master of this art. The photograph on page 184 shows the curious club-like branch end of an English Witch Elm (variety of Ulmus campestris) which has been cut back year after year to a single bud for a century and a half or two centuries at the pleached arbor in Hampton Court. This cutting holds the foliage spread nearly constant.

This cutting back operation permits the cottage owners to stunt the growth of fruit trees in the small gardens so the shade of the trees will not interfere with the growth of the vegetables and flowers. Fruits grown on walls are stunted in the same manner. In general, the stunting does not reduce the yield of fruit per foot of branch.

WHY BOX IS NOT WIDELY USED

I made many inquiries in England regarding the scarcity, of box. The answers I received from horticulturists and the ordinary garden keepers were as follows, but to my mind answer the question only in an unsatisfactory way:-

- 1"Tree box gets leggy at the ground if clipped."

- 2"All box, because of its dense interior leaves, harbors insects very badly and becomes a nuisance but is not attacked by these insects."

- 3"The other evergreens clip much better than box."

- 4"Box is out of fashion."

- 5"Mildew would hardly explain the little use."

- 6"Yew is so perfect for the purpose, why use box? Yew foliage is only on the surface of the clipped part, so the interior is free and clear of leaves."

LAWNS NOT IN ENGLAND AS IN VIRGINIA

The humidity in England is right for the most perfect evergreen lawns. The opposite is true in Virginia.

In England, lawns do not gain by nearness to shade trees. In Virginia the opposite is true, and makes a pronounced effect on the place layouts.

SHRUBBERY NOT IN ENGLAND AS IN VIRGINIA

In England, tall shrubbery is rarely planted against the walls of buildings, because the resulting dampness is objectionable, and also the obstruction of light. In England, low growing herbaceous flowering plants, thin vines (like the rose), are sometimes planted on or against buildings since the foliage of these brings or holds little moisture.

VINES NOT IN ENGLAND AS IN VIRGINIA

In England, vines of dense habit like English Ivy and euonymus are seldom used on the walls of houses, churches (except ruined churches), colleges, hospitals, because of the dampness. The same does not apply to equal degree in Virginia.

YEW NOT IN ENGLAND AS IN VIRGINIA

English Yew thrives in England because of the dampness. When clipped it will stand exposure to the hot sun without drying to death. The opposite is true in Virginia, though the Irish Yew (A.D. 1830) will thrive in Virginia.

191THE UPKEEP COST OF COTTAGE GROUNDS

This cost is not a large general cost problem as it is with us, because the Englishman is not led away from place and home to the same extent by the motor car and the movies. In general, he does not own a motor car. He takes a pride in his place which is like our pride in motors, piazza idleness, and theatre going. He stays at home with his family. They all work and putter with the garden paths, flowers, vegetables, both for the pleasure and the income.

The English cottager does not produce a large waste collection of ashes, paper containers, paper napkins, and tin cans. He burns little fuel. His supplies come in bulk from the green grocer and others. Tinned goods are a small item. He is frugal and does not produce a large by-product of garbage.

HORTICULTURAL NOTES

Taken by S. N. Shurcliff during Interview with Mr. A. Simmons, Assistant Secretary of the Royal Horticultural Society. August 12, 1932.

HOLLY

English holly has long been an important tree in England for hedges, specimen trees and other decorative work. Specimen trees grow as high as 75 feet tall in the country. In the city smoke, fog and dirt usually stunt the growth of the tree by forming a coating over the leaves.

The biggest holly hedge in England is at Keele Hall, Staffordshire. This hedge is 25 feet high and 30 feet through.

Sir Joseph Sabine who traveled all over England in 1830 described in the accounts of his travels many holly hedges which he saw.

There is one avenue of yews and hollies mixed now existing which is known to have been planted in 1654.

The variegated holly is an expensive tree to plant because it must be grafted. Consequently it is used only for specimen trees or accents; never for hedges. The variegated holly has been in use only about 100 years.

American holly is not well known in England. The first record of its introduction to England was made in 1744. Although it thrives well and is said to be decorative when the berries are profuse it has always been regarded in England as inferior to the English Holly.

English holly is not bothered by dry soil but is hard to move except in May or September. The leaves should be stripped when the tree is transplanted.

YEW

The yew is an important ornamental tree and is known to attain great size and age. In Yorkshire at Fountains Abbey the yews which are still standing were large enough to shade the workmen when the abbey was being built, 800 years ago.

There is a yew in Perthshire having a trunk diameter of 17 feet.

However, the clipped yews at Canons Ashby are probably not 235 years old as they are claimed to be. The trunks are too small to indicate such an age.

The so-called Irish yew which is merely an aspiring form of the English yew is nowhere near as old. The original Irish yew was found growing wild in 1780 by a farmer named Willis. He planted two trees from it, one in his own garden and one at Florence Court.

The first Irish yews to reach America must have arrived about 1810. Contrary to popular opinion the yew is a fairly fast-growing tree. Some Irish yews are already 35 or 40 feet tall.

PAPER MULBERRY

The paper mulberry is widely planted in the East and in the South Seas. In the South Seas it is used for making "tapa" cloth. Captain Cook noted it in Tahiti and he may have brought some back with him. It was introduced to England in the early 18th century and must have arrived in America well before 1775.

CRAPE MYRTLE

The crape myrtle is not hardy in England and must be grown in a greenhouse. It was introduced to Kew Gardens in 1759 and no doubt reached America soon afterward.

TULIP TREE

The tulip tree was one of the earliest American trees introduced to England. There was one specimen 90 feet high in England in 1745.

Tulip trees have long been popular in England and are still being planted.

AILANTHUS

The ailanthus was introduced to England from China in 1745 by Peter Collinson and no doubt reached America soon afterward.

CAROLINA POPLAR

Populus angulata, the Carolina poplar, grows to a great height in England. There is one tree 110 feet high.

SASSAFRAS

The sassafras was introduced to England in 1633 and until recently there was a large specimen growing at Claremont House. This tree was 50 feet high in 1910 and flourished well. However, there are few other sassafras trees now growing in England and it is doubtful if they were ever popular.

BOOKS ON TREES

"Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles" by W. I. Bean, in 2 volumes, is the best one on this subject. The latest edition can be purchased for about $12.00 from Selfridge's or the Army and Navy Stores.

ITINERARY OF TRIP

Sailed from New York July 28th on Bremen

Arrived Southampton August 2nd

Sailed from Southampton August 22nd on Bremen

Arrived New York August 27th, 1932.

HEADQUARTERS AND MOTORS

We made our headquarters in London and went by rail to the points nearest a group of "places". We hired motors at those points usually at the rate of eight pence per mile and a small charge extra for waiting. This system of motor hire had the great advantages of cheapness and a knowledge, on the part of the driver, of all the local roads, byways, and local interesting facts. Mr. Jellicoe went with us on several of these trips and made a very moderate charge per day (about $15) for his time. I made a personal visit to Mr. Tipping at Harefield and spent nearly a half day with him to map out the best program for our tour and to get historical data.

"PLACES" VISITED

The "places" visited were carefully chosen to give us the facts we needed. We wrote in advance (when time allowed) to get permission to visit these places, using the letters of introduction secured through Colonel Woods. I used your list of "places" and towns.

We did not visit places which I had seen and photographed on my previous English trips, like Packwood, Blenheim, Eaton Hall, Haddon Hall (Derbyshire), Pennshurt, and others. The names of places visited are included in the following day-by-day itinerary of the trip.

- August 2—

- Arrived in Southampton about 12:30 P.M. S.N.S. went directly to Ordnance Survey Office in Southampton to secure necessary surveys of old places. A2S took boat train to London and spent afternoon visiting American Embassy.

- August 3—

- A2S called on Mr. Atherton and at the English-Speaking Union. S.N.S., with difficulty, located Mr. Tipping, editor of Country Life, on `phone at Harefield, 20 miles north of London, and A2S went there to lunch. Mr. Jellicoe was present at lunch and consented to act as a guide to English gardens.

- August 4—

- A2S and S.N.S. went by train to Amersham and by taxi to Amersham-old-town, Beaconsfield, Wilton House, High Wycombe, West Wycombe, Lane's End, Great Marlowe, Wittington Place, Medmenham Abbey, Taplow Court and then took the train home from Maidenhead.

- August 5—

- A2S spent most of the morning conferring with Mr. Hake regarding Raleigh portrait for Col. Woods. About noon he and S.N.S. took the train to Hampton Court. After a two hour stay they went by boat down the Thames to Richmond where they took a taxi to Ham House and saw the grounds. Then made a short visit to Kew Gardens and went back to London by train.

- 201

- August 6—

- Visited points of interest around London:- Temple Church, British Museum, etc. Made arrangements with Mr. Jellicoe about making trips.

- August 7—

- A2S and S.N.S. took an early train to Oxford where they spent nearly an hour looking at the mounts at Wadham College and New College. Then took the train to Evesham, having lunch on the train. Hired a car at Evesham and visited Broadway, Staunton, Stanway, Hailes Abbey, Stanway House, Old Evesham, and Cleeve Prior. Then back to London by train arriving about midnight.

- August 8—

- A2S and S.N.S. visited London Zoo, Hyde Park and London slums and made personal purchases. Also visited garden at 11 Grosvenor Square as suggested in cable from Mr. Cherley. Inspected roof gardens at Selfridge's Store.

- August 9—

- A2S, S.N.S. and Mr. Jellicoe took train to Seven Oaks and hiring a taxi there visited Chevening, Knole, Great Dichter, Brickwall, Bodiam Castle, and an interesting farm house. Had dinner in Seven Oaks and arrived in London 9:45 P.M.

- August 10—

- A2S and S.N.S. spent the day visiting Chiswick House near Richmond and Claremont at Esher.

- August 11—

- A2S, S.N.S. and Mr. Jellicoe took train to Rugby and visited, by taxi, Rugby School, Newnham Paddox, Ashby St. Ledgers (scene of Gunpowder plot), Wynwick Manor, Althorp, Canons Ashby, Sulgrave Manor, and took the train back to London from Northampton.

- August 12—

- A2S sick all morning having eaten bad food. S.N.S. went to National Portrait Gallery to get message from Mr. Hake in morning. S.N.S. visited Horticultural Society for about two hours gathering plant data in the afternoon.

- August 13—

- A2S, S.N.S. and Mr. Jellicoe took the train to Gloucester. Hired a car and visited Westbury on Severn, returned to Gloucester for lunch and then went across country visiting Owlpen and St. Catherine's Court, and arriving in Bath for late dinner.

- August 14—