Architectural Report: The Old Court House Block 19 Building 3

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1420

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

THE OLD COURT HOUSE

Block 19, Building 3

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

THE OLD COURT HOUSE

Block 19, Building 3

The Old Court House on the Market Square was restored by the Williamsburg Holding Corporation under the direction of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, Architects.

Restoration was started April, 1932.

Restoration was completed October, 1932.

Walter M. Macomber, Resident Architect

A. Edwin Kendrew, Chief Draftsman

The working drawings were made by

Clyde F. Trudell and Singleton P. Moorehead

A research report was written by Dr. Hunter D. Farish in 1940.

This architectural report was prepared by A. Lawrence

Kocher and Howard Dearstyne for the Department of Architecture

(Architectural Records), reviewed by S. P.

Moorehead September 28, 1950 and corrected by A.L.K.

June 12, 1954.

August 4, 1950.

THE OLD COURT HOUSE

Located on the Market Square

Block #19, Building #3

On March 23, 1769, the Virginia Gazette carried on its third page a notice* informing its readers of the fact that the old Williamsburg court house on Palace Green was for sale and that the plan for a new court house had already been drawn up. The notices signed by the building committee of four prominent citizens of the community, James Cocke, James Carter, John Carter and John Tazewell, ran as follows:

"The Common Hall having this day determined to build a commodious Brick Court-House, in this City, and having appointed us to agree with an undertaker to build the same; we do hereby give notice that we shall meet at Mr. Hay's on Tuesday the 4th day of April, to let the building thereof.

We are also appointed to dispose of the present Court-House, and ground on which the same stands.

[Committee listed here].N.B. The Plan of the above Court House, may be seen at Mr. Hay's at any time."

It appears from the records that at the outset the building was to house only the city or "hustings" court, but that the cost of construction was found to be beyond the ability of the city to finance the undertaking. It was then that James City County was asked to 2. join with Williamsburg in the erecting of a court house to serve the needs of both city and county.

When this combination was settled upon it was discovered that the chosen site on Market Square was outside of James City County and actually in the county of York. To bridge this difficulty an appeal was made to the House of Burgesses, May 22, 1770, setting forth "that the Petitioners and the Corporation of the City of Williamsburg had, for their mutual Convenience and Benefit, entered into a Contract to build a commodious Court-House at their joint Expence; .... praying that an Act may pass for adding to the said [James City] County so much of the Market Square, in the said City, as lies on the North Side of the Main Street, as far as Nicholson Street, and between Hugh Walker's Lot and the Paling where Mr. Haldenby Dixon's Store stands ...."

A bill based on this petition was passed June 23, 1770* and, we believe that date marks the approximate time when construction of the court house was started.

No reference was found to supply detailed information on the building operation but the time of its completion is indicated by a letter of William Nelson to Samuel Martin, July 2, 1772,# which expresses thanks for "the stone steps for the Court House in Williamsburg, which came in good Order and was to the entire satisfaction of those concerned in the Building: Mr. Nicholas, I expect, will acknowledge your civility in sending them Freight free ...."

3.A BRIEF LIFE HISTORY OF THE OLD COURT HOUSE

If the Court House, as is evident from the excerpt from the letter just quoted, was completed in 1772 or thereabouts, it was the last public building erected in Virginia's colonial capital before the seat of government was removed to Richmond in 1779. It fulfilled its functions as a city and county courthouse for over a century and a half, until 1932, indeed, when, in the course of the restoration of the colonial town, a new and more commodious court house was built south of the Market Square and the old building was turned into a museum.

During its long existence, and before being retired to become a museum for the display of objects from Williamsburg's colonial past, the Court House experienced its fair share of calamities, very much as did the Capitol, Hospital and the Governor's Palace. It fared somewhat better than these, however, since it alone survived the vicissitudes of fire, war and usage.

Shortly after its completion, during the Revolution, the building was pressed into service as a barrack. Many an auction, in the course of which slaves and household goods were disposed of, was held on its steps. It underwent its greatest trial on April 6, 1911, when, about one o'clock in the morning, a student of the College named English, who was crossing the Market Square green, discovered the building in flames. The local newspaper, following the event, stated that "The fire alarm being the courthouse bell, practically no alarm was sounded. For this reason ... not more than a hundred saw the ruin of the cherished old structure."*

4.The news report further informs us that the roof and cupola, as well as the inside woodwork and flooring were destroyed but that the outer walls remained standing and suffered no serious damage. A few months later the entire building, with the exception of the brick walls, was rebuilt. Some minor changes were made consisting chiefly of provisions for rendering the building fireproof. This reconditioning of 1911 involved the thickening of the outer walls by 4 inches and reinforcing them by cross-rods, and adding iron shutters to the windows. All the exterior woodwork was renewed and four columns of the Doric order, built of brick surfaced with cement, were erected to complete the reclamation of the famed landmark.

THE OLD COURT HOUSE AS RESTORED AFTER THE FIRE OF 1911 SHOWING THE FOUR NEW DORIC COLUMNS

THE OLD COURT HOUSE AS RESTORED AFTER THE FIRE OF 1911 SHOWING THE FOUR NEW DORIC COLUMNS

Following its restoration the building soon returned to its older town court-house character. It now had taken on a spruced up appearance because of fresh paint and its newly-acquired columned portico. The porch again became a favored lounging place, directly opposite another town hangout, the Circle Club, which adjoined the Public Magazine. It was the meeting place of town characters and politicos, and a well-spring of local gossip. In order that the sitters might not have to seat themselves on the hard stone steps, a local merchant had donated, 5. expressly for their comfort, a pair of orange-colored benches bearing in large black letters the hospitable inscription, "Rest here in a Garner Suit."

In this, its first restored state, the Court House continued on as the quiet center of city and county government. It altered not 'till the year 1927 when Mr. Rockefeller made the decision to undertake the fulfillment of Dr. Goodwin's plan "to restore the significant portions of an historic and important city of America's colonial period." The restoration of the Court House followed in its turn, in the early part of 1932, and, as was stated above, the venerable building became, thereafter, a museum.

THE ENIGMA OF THE FOUR MISSING PILLARS

There is an oft-cited tradition to the effect that it was intended originally that the Court House have a portico of four stone columns. These, we are told, were to have arrived along with the stone steps. No item has been found in the records to substantiate the claim that stone columns were imported from England, or, in fact, that any columns were intended for the support of the pediment. At the same time the probability remains that columns were actually in place at one time during the colonial period. This supposition is supported by the likelihood that the architect or builder of a structure as carefully thought out as this would have wished to consummate his design scheme by bringing every part to completion. No single instance, furthermore, of a columnless pediment of any size was found in reviewing many examples of colonial pedimented buildings.* Hoods 6. of slight projection, unsupported by columns, are found, of course, on colonial buildings in Williamsburg and its environs; well-known examples are the old hood over the north entrance doorway of the President's House of the College of William and Mary and the one over the west entrance doorway of Tuckahoe in Goochland County. The typical "Germantown Doorway," such as that of the Johnson House in Philadelphia, also has a projecting hood. These examples are too small, however, to be comparable with the pediment of the Court House, so that they could hardly be considered to have constituted a precedent for omitting columnar supports in the latter case.

When the columns, if they existed in the eighteenth century, disappeared and why, remain unanswered questions. We know from old drawings, photographs (see illustrations on following page) and records

7.

Water color drawing (about 1858-59) by L.J. Cranston showing the columnless Court House with the Peyton Randolph House in the background.

Water color drawing (about 1858-59) by L.J. Cranston showing the columnless Court House with the Peyton Randolph House in the background.

Photograph of the Court House made in the 1870s. It will be noted that the "dome" and sides of the cupola were metal-clad at that time.

that the Court House had no columns from the middle of the nineteenth century down to 1911 when, after the building burned, four Doric columns were placed under the pediment. It was because of this evidence that these recently-installed columns were removed in the course of the restoration of the building by Colonial Williamsburg. The riddle as to whether or not the Court House was pillarless in the eighteenth century still remains, however, and the question will doubtless be debated for years to come — until, in fact, the discovery of new evidence definitely proves or disproves their existence at the time the building was first erected.

Photograph of the Court House made in the 1870s. It will be noted that the "dome" and sides of the cupola were metal-clad at that time.

that the Court House had no columns from the middle of the nineteenth century down to 1911 when, after the building burned, four Doric columns were placed under the pediment. It was because of this evidence that these recently-installed columns were removed in the course of the restoration of the building by Colonial Williamsburg. The riddle as to whether or not the Court House was pillarless in the eighteenth century still remains, however, and the question will doubtless be debated for years to come — until, in fact, the discovery of new evidence definitely proves or disproves their existence at the time the building was first erected.

ANOTHER RIDDLE — WHO DESIGNED THE COURT HOUSE?

It has long been recognized that the Old Court House has superior qualities as an architectural conception. The precise proportioning of its parts as well as the effective spacing of its arched windows and doors suggest that it was designed by an architect or master builder. In any event the designer followed closely the formulas for the proportioning of facades and elements of facades such as doors and windows which are found in classical handbooks like Abraham Swan's Designs in Architecture and William Pain's The Builder's Companion. Both of these guides to the builder and amateur architect were advertised for sale at the Gazette office in Williamsburg in the Virginia Gazette of August, 1771.

Because of the distinction of its design the name of Sir Christopher Wren became associated with the building and he is referred to repeatedly as its author.* It would be extremely difficult, however, to establish a link between the Court House and Wren since the later died in 1723, almost a half century before work on the building was started!

It is more reasonable to turn to the Tidewater locality to establish its origin. In plan and appearance, the Williamsburg Court House resembles the Gloucester Court House, known to have been built a 9. few years earlier — in 1766. The "T" form occurs at Gloucester and for over a century this was to be the pattern for many another Virginia example. While the plan type can thug be seen to be indigenous to Virginia, we turn to Williamsburg itself for the answer to the question as to who actually designed the building.

The decade beginning in 1769, when the building committee for the Court House advertised for an undertaker to carry out the construction of the building, was important in the architectural history of Williamsburg, not alone for the projects carried to completion but also for certain ones which were proposed but never executed. Among the latter projects were the proposal made by Thomas Jefferson for the completion, at the College of William and Mary, of the quadrangle of which the Wren Building with its dependent chapel and refectory represented only half of the building complex as originally conceived, and his scheme for the alteration and rehabilitation of the Governor's Palace, then in a semi-ruinous condition. The Revolutionary War caused the abandonment of both of these projects.

Two projects of major importance were carried to completion, however, before the hostilities pat an end to building in Williamsburg for a number of years. These two projects were the Old Court House and the Hospital for the Insane, the first building of its type to be erected in America. The circumstance of importance to us at the moment is that these two structures were being designed and erected at almost precisely the same time.

We know the architect of the Hospital for the Insane; it was Robert Smith of Philadelphia, one of colonial America's most gifted 10. architects. This simultaneous building of the two structures, we feel, is, possibly, of very considerable significance. What would be more reasonable, with the House of Burgesses reaching beyond the confines of Virginia to secure an architect of reputation to design the Hospital, than that the city and county should likewise employ the talents of the same man in the design of the Court House? We have no documents to prove that Robert Smith designed the Court House; possible clues of this sort may have been destroyed in the fire of 1911 which consumed all of the Court House records. But the circumstance that both the Court House and the Hospital were building at the same time, together with the fact that similarities exist in the planning and detailing of the Court House and the architectural works of Robert Smith point to the Philadelphian as the architect of the Court House.

It is also of significance here that Robert Smith was at this very time (1769-1771 approximately) designing and executing Carpenter's Hall in Philadelphia, the famous structure which housed the First Continental Congress (1774), the Provincial Assembly (1775-1776) and the Constitutional Convention (1787). The significance derives from the similarity in the plans of the Court House and Carpenter's Hall. Carpenter's Hall, of course, was a two-story building, but the first floor plan of the Hall is strikingly similar to the plan of the Court House, as an examination of the chart on page 10a will reveal. Both buildings are basically cruciform (one need but enclose the porch of the Court House to make this actually so.) The two buildings are quite close to the same size as the dimensions given on the chart reveal. It is rather remarkable to find that the

10a.

PLANS OF THE OLD COURT HOUSE, CARPENTERS' HALL IN PHILADELPHIA AND THE FIRST HOSPITAL FOR THE INSANE IN WILLIAMSBURG, JUXTAPOSED TO FACILITATE A COMPARISON OF THEIR FEATURES.

10b.

PLANS OF THE OLD COURT HOUSE, CARPENTERS' HALL IN PHILADELPHIA AND THE FIRST HOSPITAL FOR THE INSANE IN WILLIAMSBURG, JUXTAPOSED TO FACILITATE A COMPARISON OF THEIR FEATURES.

10b.

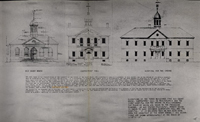

ELEVATIONS OF THE OLD COURT HOUSES, CARPENTERS' HALL IN PHILADELPHIA AND THE FIRST HOSPITAL FOR THE INSANE IN WILLIAMSBURG SHOWN TOGETHER TO PERMIT A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THEM.

11.

Court House is actually a bit larger than Carpenter's Hall which one might have imagined to be a more pretentious building considering the momentous assemblages which were held therein.

ELEVATIONS OF THE OLD COURT HOUSES, CARPENTERS' HALL IN PHILADELPHIA AND THE FIRST HOSPITAL FOR THE INSANE IN WILLIAMSBURG SHOWN TOGETHER TO PERMIT A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THEM.

11.

Court House is actually a bit larger than Carpenter's Hall which one might have imagined to be a more pretentious building considering the momentous assemblages which were held therein.

If a comparison of the plan of Smith's Hospital for the Insane and Carpenter's Hall reveals no similar features it should not be considered extraordinary even if we accept the thesis of a common authorship of the two buildings. After all, the functions of these buildings were completely different.

A comparison of the front facades of the three buildings under consideration (see chart, page lOb) shows them to possess certain features in common. The towers or cupolas are all of the same general character and all three buildings have, as the chief motive of the front facade, a pediment. This feature, by the way, was not characteristic of Williamsburg building, though of course, the previously-mentioned Gloucester Court House, built a few years before the Williamsburg court building, had the feature. In comparing the front elevation of Carpenter's Hall with that of the Court House allowance must be made for the fact that the former facade was considerably altered in the nineteenth century. Its detailing may originally have resembled that of the Court House front more closely.

It is not without importance, if we believe that the Court House possessed a portico at one time in the eighteenth century, that columns were also employed on the front of the Hospital. The significance of this lies in the fact that the use of classic columns in this way was unusual at the time the Hospital was built. One must remember that Thomas Jefferson had then not yet designed his Richmond Capitol, which is considered one of the earliest examples of the use of a classic portico in this country.

12.The evidence which points to Robert Smith is far from complete. It is nevertheless very good and, we feel, it is by far the most reasonable answer yet put forth to the question of who designed the fine little building on the Market Square.

THE PROPORTIONING OF THE FACADES OF THE COURT HOUSE

An excellent reason for assuming that the Old Court House was designed by a trained and well-qualified architect is the fact, alluded to before, that the facades are carefully detailed and are satisfying in the relationship of their parts. The architect (Robert Smith or someone else, if Smith was not the actual designer) followed principles of proportioning which were highly thought of and widely practiced by competent architects of the eighteenth century. These architects produced designs founded upon what they termed "arithmetical Harmony," which involved the use of the square, the circle and the cube as the basis of the shapes of building elements. Robert Morris in his Lectures on Architecture (London, 1734) gives a list of the rules to be followed in obtaining "Harmonic and Arithmetical Proportions in Buildings." "In the case of the square," says Morris, "the parts being equal, the sides, and angles give the Eye and Ear an agreeable Pleasure; from hence may likewise be deduced the cube, the cube and a half and the double cube."

Not the least among the architects who used geometric aids in establishing the proportions of a building was Thomas Jefferson. The reproduction shown on the following page of an original drawing by Jefferson for the Rotunda of the University of Virginia reveals that the statesman-architect so designed the building that its height, width and depth were all the same, in other words, in such a manner

13.

ELEVATION AND SECTION OF ROTUND OF UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA WHICH SHOW THAT THOMAS JEFFERSON BASED THE PROPORTIONS OF HIS DESIGN ON THE CIRCLE AND THE CUBE.

that the whole might be contained within a cube.

ELEVATION AND SECTION OF ROTUND OF UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA WHICH SHOW THAT THOMAS JEFFERSON BASED THE PROPORTIONS OF HIS DESIGN ON THE CIRCLE AND THE CUBE.

that the whole might be contained within a cube.

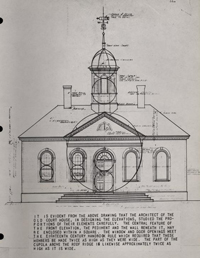

An examination of the drawing of the street facade of the Court House (next page) will make it evident to the reader that the architect of this building also followed similar geometric principles of proportioning. The central feature, the pediment and the portion of the wall directly beneath it can be contained in an exact square. The door and window openings fulfill the established eighteenth century handbook rule of being twice as high as they are wide.* The portion of the domed-topped cupola above the level of the roof ridge is also approximately two diameters high. This careful study of the proportions of the mayor features of the facade is combined, in the Court House, with the painstaking design of all of the other details of the structure.

14. IT IS EVIDENT FROM THE ABOVE DRAWING THAT THE ARCHITECT OF THE 0LD COURT HOUSE, IN DESIGNING THE ELEVATIONS, STUDIED THE PROP0RTIONS OF THEIR ELEMENTS CAREFULLY. THE CENTRAL FEATURE OF THE FRONT ELEVATION, THE PEDIMENT AND THE WALL BENEATH IT, MAY BE ENCLOSED WITHIN A SQUARE. THE WINDOW AND DOOR OPENINGS MEET

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY HANDBOOK RULE WHICH REQUIRED THAT THESE MEMBERS BE MADE TWICE AS HIGH AS THEY WERE WIDE. THE PART OF THE CUPOLA ABOVE THE ROOF RIDGE IS LIKEWISE APPROXIMATELY TWICE AS HIGH AS IT IS WIDE.

IT IS EVIDENT FROM THE ABOVE DRAWING THAT THE ARCHITECT OF THE 0LD COURT HOUSE, IN DESIGNING THE ELEVATIONS, STUDIED THE PROP0RTIONS OF THEIR ELEMENTS CAREFULLY. THE CENTRAL FEATURE OF THE FRONT ELEVATION, THE PEDIMENT AND THE WALL BENEATH IT, MAY BE ENCLOSED WITHIN A SQUARE. THE WINDOW AND DOOR OPENINGS MEET

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY HANDBOOK RULE WHICH REQUIRED THAT THESE MEMBERS BE MADE TWICE AS HIGH AS THEY WERE WIDE. THE PART OF THE CUPOLA ABOVE THE ROOF RIDGE IS LIKEWISE APPROXIMATELY TWICE AS HIGH AS IT IS WIDE.

| CARPENTERS' HALL | HOSPITAL | OLD COURT HOUSE |

|---|---|---|

| 1763 Comm. App'd by Carp. Co. to select site in Phila. | ||

| 1766 Governor Fauquier recommended the establishment of "a hospital at Williamsburg for persons of disordered minds". | ||

| 1768, Feb. 3 Site obtained-66 ft. on Chestnut St. & 255 ft. in depth. | 1768-69 Agreement of the County of James City and the City of Williamsburg "to erect at their joint expense, a court house on the market square in the said city." | |

| 1769-70 Plan by Robert Smith adopted. | 1769 Nov. Act for the establishment of the Hospital passed by the House of Burgesses.* | 1769, March 23 Advertisement for undertaker for new court house (Virginia Gazette). Old Williamsburg hustings court building on Palace Green offered for sale. |

| 1770 Work started Feb. 5, 1770. | 1770 Plan, dated, April 9, 1770, furnished by Robert Smith, Phila. | |

| 1771 Feb. 21, First meeting — in unfinished building. | 1771 Date of contract with builder. | |

| 1772 Receipt of stone steps ordered from England acknowledged by William Nelson, President of the Council. | ||

| 1773 Sept. 14, Hospital, with additions, declared completed. | ||

| 1774 Sept. 5. The First Continental Congress met in Hall. | 1774 Meeting held at Court House. | |

| 16. | ||

| 1775-76 Provincial Assembly met there. | ||

| 1777 British occupy Phila. and the Hall. Red coats make target of weathervane. | ||

| 1787 Constitutional Convention held there | ||

| 1792 Date of completion of the building. | ||

| 1891-92 Hall partly remodeled. | ||

| 1911 Interior of Court House consumed by fire. Building restored by City of Williamsburg. | ||

| 1932 Court House restored to its present form by Colonial Williamsburg. | ||

An Account of the Sheathing of the Old Court House Cupola and the Roof

"In pre-1911 photos the cupola of the old Court House of 1770 is shown sheathed in tin. One view among the progress photographs (N-3364) shows round-butt wood shingles on the main roof. Another view (N-5202) shows a slate roof with metal covered ridges. The Cranston watercolor drawing (N-4004) indicates a tin-covered cupola, dated 1858-9."Information from S. P. Moorehead,

September 28, 1950.

THE EXTERIOR OF THE COURT HOUSE DISCUSSED IN DETAIL

(Some of the information contained in this portion of the report represents a re-working of material found in the architectural report of Clyde F. Trudell of November 10, 1932. Much new information has been added, however.)

BRICKWORK

General

Under this subject heading is included the brickwork of the main foundations and those of the bulkhead, the exterior walls, the chimneys and the brick gutters which exist at the base of all the exterior walls except the south wall.

Except for some necessary patching the walls and foundations are of original brickwork, which survived the fire of 1911, The water table, and also the chimneys and brick gutters are replacements of the original features. These are made of old brick from the Colonial Williamsburg stock pile of eighteenth-century brick.

Color

The brick color is variegated. One finds in the walls brick of diverse shades of salmon red, reddish purple, purple, and buff. Brick of a deep salmon red seem to predominate. Singleton P. Moorehead made the interesting observation that the fire of 1911 may have caused some of the brick to become darker in color.

There are a considerable number of glazed headers scattered among the brick of the wall. Even though the flaking off of some of the original glazing would tend to obscure what might have been a pattern of glazed headers, it is unlikely that such a pattern ever existed on the walls. Glazed brick, used as accents in the upper half of the 18. brick window and door arches, still form a pattern, however, of alternating glazed and unglazed headers.

Bond

The bond throughout is Flemish above the water table and English below it. The brick are laid in oystershell mortar and the joints are tooled.

Decorative Brickwork

Though extensive weathering somewhat obscures the fact, the brickwork of the arches and jambs of the door and windows, and at the corners of the building, was evidently at one time ground to distinguish it from the surrounding brickwork. A deeper red in the color of this brickwork still sets it apart from the brickwork of the walls as a whole.

The architect of the building sought to enhance the decorative effect of the brick arches further by the creation of "keystones" and imposts of brick raised about 1 ¼" from the surface of the wall. These original features still exist.

Sizes

The brick of the walls are surprisingly uniform in size, which doubtless signifies that they were made at one time. The chart below,

BRICK SIZES-OLD BRICKWORK OF COURT HOUSE

19.

made from measurements on several walls of the building, gives the size

range.

BRICK SIZES-OLD BRICKWORK OF COURT HOUSE

19.

made from measurements on several walls of the building, gives the size

range.

Foundations

The foundations, that is, the extension of the brick walls beneath the surface of the ground, and the walls of the basement are, like the walls above ground, original brickwork.

Bulkhead

The brick walls of the bulkhead are recent, however, since this entire feature (walls and inclined wood doors) was added when the first heating plant was installed about 1911. When Colonial Williamsburg, Inc. restored the building the existing doors were replaced by new doors fashioned after colonial examples. Old bulkheads with sloping tops which may well have served as precedent for this one are the bulkheads of Captain Orr's Dwelling and the Taliaferro-Cole Shop in Williamsburg.

Water table

The simple sloping water table is a replacement of a similar old water table which was in poor repair. The brick used were old brick from the "antique" brick stock pile of Colonial Williamsburg, Inc.

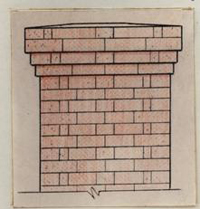

Chimneys

Both chimneys have been relined and rebuilt to the size, height and detail of the original chimneys. Old brick from the antique brick stock pile were used in the work.

BRICK CAP OF COURT HOUSE CHIMNEYS

BRICK CAP OF COURT HOUSE CHIMNEYS

Gutters

Ground level gutters of old brick from the stock pile were placed adjacent to the walls on all sides of the building except the south front. These gutters are three brick-lengths wide. They empty into drains at the four north corners of the building. The gutters follow in their design the character of similar eighteenth century ground-level gutters found in Williamsburg. An example of an old brick gutter found locally is the one of which fragments still existed at the Barraud House at the time of the restoration of that building.

Hearths

There are, within the building, two corner fireplaces, in the southwest and southeast rooms, respectively. The mantels are new and follow local colonial precedent. The hearths and remaining brickwork of the fireplaces are also new, but are made of old brick from the stock pile.

STONE MASONRY

The stone platform or porch with its three stone steps (see frontispiece and plan, page 10a) is new and was patterned after the steps which existed before the fire of 1911. Old photographs such as that on page 7 were consulted in determining the design. They were made of Pennsylvania blue stone, although Mr. John S. Charles, an old resident of the town, remembered them as having been of red sandstone.

The profile given the nosings of the steps (a half-round beneath which are a fillet and a cove) is a type found frequently on eighteenth-century stone steps in Virginia. For example, though the sizes vary considerably, the nosings of the old steps of the John Blair 21. House, the President's House of the College of William and Mary and of nearby Carter's Grove are very similar to those used on the Court House steps. (For a comparative study of several old examples of nosings, see page 18 of the Architectural Report on the Pitt-Dixon House, Block l8-2.)

ROOF

The roof form in plan is that of a Greek cross. The roof is essentially two intersecting A-roofs, with the cupola resting on what would be, were it not for its presence, the point of intersection of the two ridges. The "A's" terminate on the north east and west ends in hips and on the south in the pediment. The ridge of the portion of the roof which forms the hood or porch overhang is somewhat lower than the other ridges.

The fire of 1911 destroyed the roof so that it had to be reconstructed. In this reconstruction of 1911 the cornice was placed 2 1/2 brick courses lower than it had been before the fire and the roof ridge was also lowered accordingly. In the final restoration in 1932, both the cornice and the roof were restored to their original, slightly higher elevations.

The roof construction, generally, follows present practice in the construction of hipped A roofs (see working drawings Nos. 4 and 5). Support had to be provided, however, for the cupola and this was accomplished by means of two king-rod trusses running in an east-west direction and resting on the transverse walls of the main room of the Court House.

The cantilevered roof of the portico, which has an overhang of about 8 feet, is supported, in the main, by two wood beams extending 22. back into the building a distance approximately equal to the overhang. These beams rest on the transverse walls of the main room and are anchored to it. In addition to the 2" x 12" rafters which form the mayor part of the framework of the porch roof, there are, at the center of the overhang, two 2" x 12" diagonal braces forming a cross beneath the ridge which serves as a stiffener.

Roof Covering

The roof is covered with square-butted asbestos-cement shingles made to simulate weathered wood shingles. The material of these shingles is fireproof and they were used here as they are used on all but very minor buildings in the restored area as a fire-prevention measure.

EXTERIOR AND INTERIOR WALLS

The exterior walls have already been discussed at some length under "Brickwork". Mention should be made, however, of the thickness of the walls. The outside walls are, throughout, 1'-8" thick above the water table. outer walls made 4" thicker in 1911The water table projects 2 ¾", so that the wall below it is 1'-10 ¾" in thickness.

On the interior, in the course of the restoration of 1932, the brick walls between the main room and the smaller "offices" were reduced in thickness from 1'-4" to 1'-1". The fireproof vault built after the fire of 1911 no longer being necessary, the heavy (1'-8") wall between the vault (northeast) room and the southeast room was removed and a 6" partition substituted for it.

The interior surfaces of all brick walls were furred and replastered in the course of the refinishing of the interior.

EXTERIOR TRIM

Cornice

This is new but it is a careful copy of the cornice which existed before the fire of 1911. Old photographs were studied to determine its details. As was stated previously, in restoring the building in 1932, the cornice was raised 2 ½ brick courses to the line of the original cornice. This cornice is richer in detail than most Williamsburg cornices, possessing both modillions and dentils.

Pediment

The cornice continues along the front and sides of the base of the porch overhang and ascends the two sloping sides which complete the triangle of the pediment. Beneath the cornice, on the horizontal front and sides of the porch overhang, is a pulvinated frieze and below this the three "retreating" fascias which constitute the architrave. These three members form a complete classic entablature in the Ionic style, one of the few examples of such an entablature in Williamsburg. (Another example is that of the porch of the James Semple House.)

The triangle of the pediment has a semi-circular "window" opening provided with wood louvres for ventilation. The face of this triangle, except for the space occupied by this vent opening, is covered with flush, random-width horizontal boarding.

The recessed soffit of the porch is plastered — a treatment commonly used on porches in the eighteenth century. An old local example of a plastered porch soffit is that of the west porch on the south side of the Coke-Garrett House.

24.All of the elements of the pediment are new but they were all fashioned after corresponding features of the pediment which old photographs reveal existed before the fire of 1911.

BULKHEAD AND BASEMENT

The bulkhead has already been discussed on page 19. The bulkhead covers the steps which lead to the basement. The latter occupies a space about 11' x 26' under the northeast corner of the building and houses its heating system. The remainder of the space beneath the Court House is unexcavated.

WINDOWS

The windows are 14 in number and they are all alike in size and detailing. They are distributed as follows: four on the south front; three each on the east and west fronts and again four on the north side (or sides) of the building.

The windows are of a scale appropriate to a public building of this character- approximately 4' x 10'. They are round-arched and the arches and jambs (as has been stated on page 18) are made of ground or rubbed brick, with glazed headers and projecting key block and imposts lending an added richness to the brickwork of the arches.

The windows are four lights wide. The lower sash are three lights high while the upper sash have, in height, three rectangular panes, above which, in the semicircle of the arched opening, are a half-circle of four wedge-shaped panes, beneath which two panes which are quarter-circular complete the glazed half-disk.

The exterior trim of the windows is of the single-molded type. The sills are of the molded variety, terminating on the outside in a half-round, beneath which is a short fascia and a cove

25.The window sash, frames, trim and sills are new. The semicircular heads of the sash are similar to those of Ware Church in Mathews Co. and, in fact, a number of other Virginia churches. The single molded trim is the type which was commonly found throughout Williamsburg in the eighteenth century. Molded sills such as those used on the Court House were also quite common in the town. Old examples which still exist are a sill on the north side, northwest corner of the Taliaferro-Cole House and sills at the Bracken House.

DOORWAY

The doorway — in this case, the brickwork opening — is, as befits this public building, of ample proportions, being about 6'-9" wide by 14' high. The door is of the two valve type, each leaf of which has eight panels on each side — two series of two square panels above two elongated panels, the upper rectangular panels being considerably longer than the lower. The doors, themselves, are about 10' high and above them is a fanlight transom, composed of two concentric semi-circles of wedge-shaped glass panes.

The exterior trim is of the double-molded variety which was in widespread use in this locality during the eighteenth century. The interior trim is a simple flat band, beaded at the corner toward the door opening.

The door sill is a square-cut stone slip sill which projects about ½" beyond the face of the brickwork and rests, on the outside, on the stone floor of the porch. The sides of the sill line up with the outer edge of the door frame.

No colonial original of this doorway, as a whole, has been found, but all of the elements of which it is composed were in common 26. use in eighteenth-century Virginia. Ampthill, formerly in Chesterfield County, Carter's Grove, near Williamsburg and the President's House of the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg originally had 8-panel single-leaf doors of the type of the Court House doors. Fanlights of many varieties, including this simple type with its semi-circular bands of glass were common enough in all of the colonies, Virginia included, in colonial times.

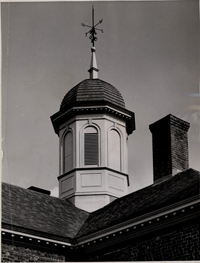

CUPOLA

The cupola was, of course, destroyed in the fire of 1911 and, consequently, it was rebuilt by the city after the fire. In the course of rebuilding the roof during the restoration of 1932, the cupola was once again reconstructed. Care was taken in this reconstruction to follow as closely as possible the form of the tower as revealed by the pre-fire photos, one of which, at least, went back to the pre-Civil War period.

Attention has already been called (chart, page 10b) to the similarity, as to general type, of this cupola and the cupolas designed by Robert Smith for the Hospital for the Insane in Williamsburg and Carpenter's Hall in Philadelphia. To compare the Court House cupola with other cupolas in Williamsburg, all of which are, of course, reconstructed, one can say that it is somewhat similar to that of the Wren Building and very unlike those of the Governor's Palace and the Capitol. The Court House lantern is, in plan, an octagon, and it is surmounted by a dome formed of eight contiguous spherical triangles. Each of the eight wood sides beneath the dome has, superimposed on it, an arched "window" frame which rests on the cap of the paneled base 27. below it. Each arch has a blank key block. Four of the "openings" are provided with inclined wood louvres for ventilation and the other four are faced with random-width, unbeaded, flush boards.

The dome, with its inclined straight splay at the bottom, which forms an apron over the modillion cornice above the arched bays, is covered, for fire safety, with asbestos-cement shingles. Surmounting the dome is a wood shaft terminating in a ball, which supports the wrought-iron weathervane (see frontispiece). This weathervane is the old one which survived the fire of 1911. It was necessary to repair certain parts of it.

SHUTTERS

Outside shutters existed on the windows of the building both before and after the fire of 1911. The shutters shown in the old photographs were, however, late in character. It was believed that the original Court House did not possess outside shutters, so these were omitted from the windows in the final restoration of the building.

THE INTERIOR OF THE RESTORED COURT HOUSE

The building was restored with the intention of using the interior as an archaeological museum so that no attempt was made to restore the court room and adjoining offices as they were originally.

The former court room (the main, central room) was finished in a simple manner with plaster walls and ceiling, atypical wood cornice and an old panelled dado of window-sill height which was taken from a house in Jarrett, Virginia.

A depressed entrance vestibule which had been built on the inside in the course of the restoration of 1911 was removed, as was the elevated platform for the judge's bench, jurors, etc. which occupied the north end of the room. A new floor was constructed in this main room, including new floor joists and finish flooring. The flooring placed in this room and all the secondary rooms, except the toilets and janitor's closet which occupy the former vault room at the north side of the east wing, where linoleum was used, is old pine flooring varying in width from 4" to 7". This flooring is face-nailed in colonial fashion with modern cut nails made to simulate old nails.

The corner fireplaces (one in each of the two end rooms on the south side of the building) were problematical as they had been so often rebuilt and blocked out. In restoring them they were given a size and detailing which was typical of local colonial fireplaces.

The interior of the building is equipped with show cases, wall displays etc. for the exhibition of old objects recovered from excavations made in Williamsburg and from other sources. The southwest room has now been fitted out as a lounge or reading room for the use of visitors to the museum.

PAINTING AND COLOR

The following colors are at the present time (August 4, 1950) used on the exterior and interior of the Old Court House:

| No. | Location | Finish | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceiling of Porch | Blue | ||

| 271 | Exterior trim and cupola | White with greyed yellow | |

| 168 | Benches on porch | Varnish | Dark umber (reddish brown) |

| No. | Location | Finish | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Woodwork, main central room | Satin | Mulberry |

| 698 | Walls and ceiling of above room. | Dri-wall | |

| 200 | Woodwork, northwest room | Satin | Grey tan |

| 255 | Woodwork, southwest room | Minus varnish | Pale off white (fawn) |

| 221 | Woodwork, southeast room | Satin | Dark grey green |

| 221 | Woodwork, janitor's closet, ladies' and gents' rooms. | Satin | Dark grey green |

| 698 | Walls and ceiling of above rooms | Dri-awl | |

| 697 | Fireplace facings | Flat black | |

| 175 | Baseboards | Flat black |

A. Lawrence Kocher.

Howard Dearstyne

Williamsburg, August 4, 1950

Footnotes

Though church interiors in which the roof is supported by columns against which balconies abut at either side were not unusual in certain of the other colonies, they were rare in Virginia. It is, therefore, not remarkable that the vestry in this case decided to omit the columns. The specified roof construction, presumably, was of such strength that the columns would have been more ornamental than essential.

A different theory as to the authorship of the plans for the Court House is advanced by Thomas Waterman in his Mansions of Virginia, p. 397. Waterman believes that the building is the work of Thomas Jefferson or Richard Taliaferro.

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS USED IN ARCHITECTURAL RECORDS

(This glossary is appended as an aid in the interpretation of certain terms used in the report, which are frequently subject to misinterpretation.)

The word "existing" is used in these records to designate features of the building which were in existence prior to its restoration by Colonial Williamsburg."

The phrase "not in existence" means "not in existence at the time of restoration."

The word "modern" is used as a synonym of "recent" and is intended to designate any feature which is a replacement of what was there originally and which is of so late a date that it could not properly be retained in an authentic restoration of the building. It must be understood, however, that restored buildings do require the use of modern materials in the way of framing as well as modern equipment.

The word "old" is used to indicate anything about a building that cannot be defined with certainty as being original but which is old enough to justify its retention in a restored building as of the period in which the house was built.

The word "ancient" when used in these reports is intended to mean "existed long ago" or "since long ago." Because of the looseness of its meaning, the term is seldom used but when used, it denotes great age.

"Antique" as applied to a building or materials, is intended to mean that these date from before the Revolution.

31.It is to be noted that the existing roof covering, whether original or modern, has been replaced in all of the restored buildings—with a few minor exceptions, by shingles of fireproof material (asbestos cement) because of the desirability of achieving protection against fire.

When we say "reconstruction (or restoration) was started" the actual beginning of work is meant, not authorization which may occur at an earlier date.

When we say "reconstruction (or restoration) was started" the actual beginning of work is meant, not authorization which may occur at an earlier date.

When we say "reconstruction (or restoration) was completed," we refer to the actual completion date of the building and not to the date when the building was accepted.

DATING OF A BUILDING

The dating of a house or other building is based upon one or more of the following:

- 1.Actual date of the house visibly signed on its brickwork, framework, etc.

- 2.Literary references such as:

- a.A record stating when a building was started, was in course of erection or completed.

- b.A record which would imply that a house was being occupied at a given date.

- c.Correspondence referring to a house as under construction or as having been completed.

- d.Advertisements referring to a house as for sale or implying its existence.

- e.House transfers by will (wills frequently contain inventories of the contents of a house), sale or default in payment.

- f.Fire insurance policy declarations.

- 3.Documentary evidence such as that furnished by maps; buildings may be indicated on maps, the dates or approximate dates of which are known.

- 4.Historical references to the building such as found in the record of the meeting at the Raleigh Tavern in 1765 to defy the Stamp Act.

- 5.Existence of original plans or draughts of a building; drawings of exteriors of buildings such as Michel's drawing of the exterior of the Wren Building and of the elevations of Williamsburg buildings shown 33. on the Bodleian Plate (1701, 1702); drawings of interiors of buildings such as Lossing's sketch of the interior of the Apollo Room of the Raleigh Tavern, made in 1850, etc.

- 6.Design characteristics.

- 7.Archaeological evidence and artifacts. (The Division of Architecture of Colonial Williamsburg has developed a chronology of pottery and porcelain which is of assistance in approximating the period of usage of the fragments found on the site.)

OLD COURT HOUSE

Block 19, Building 3

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- .Research report by Dr. Hunter D. Parish, 1940

- .Architectural Report by Clyde F. Trudell, Nov. 10, 1932

- .Architectural Reports on other Williamsburg buildings give data relating to architectural details of the Old Court House

- .Recollections of Williamsburg, Mr. John S. Charles, in Department of Research and Record.

- .William and Mary Quarterly

- .Files of Virginia Gazette, used with the aid of the Virginia Gazette Index, compiled by Lester Cappon and Stella Duff.

- .E. G. Swem; Virginia Historical Index

- .Journals of the House of Burgesses

- .Vestry Book of Stratton Major Parish

- .Lyon G. Tyler, Williamsburg, The Old Colonial Capital, Richmond, 1907.

- .Rutherfoord Goodwin, A Brief & True Report Concerning Williamsburg in Virginia, Williamsburg, 1940

- .Herbert C. Wise and H. Ferdinand Beidleman, Colonial Architecture for Those About to Build, Philadelphia, 1913.

- .William Rotch Ware, Editor, The Georgian Period, 3 vols., Boston, 1901

- .Thomas Tileston Waterman and John A. Barrows, Domestic Colonial Architecture of Tidewater Virginia, New York, 1932

- .Thomas Tileston Waterman, The Mansions of Virginia, Chapel Hill, N.C., 1946

- .Wyndham B. Blanton, Medicine in Virginia in the Eighteenth Century, Richmond, 1931.

Books, Newspapers, and Reports

- .Specifications for the construction of Hospital for the Insane by Robert Smith, dated April 9, 1770. These are in the possession of the Eastern State Hospital, Williamsburg.

- .Correspondence, General Files of Colonial Williamsburg, Inc. Files of letters concerning the Old Court House written by and to the architects, Perry, Shaw and Hepburn.

Documents

- .Photographs of the Old Court House, before and after the fire of 1911 and following the restoration of 1932 are found in the Progress Photograph file of the Architectural Department.

Photographs

- .The Old Court House is shown on the Frenchman's Map of 1782.

Maps

- .Measured drawings of the building as it was before the restoration of 1932 and working drawings for its restoration are found in the working drawing files of the Architectural Department.

- .The specifications used in restoring the building in 1932 are found in the specification file of the Architectural Department.

Drawings and Specifications

- .This contains much information concerning eighteenth century building practices in Virginia.

Glossary, Architectural Records Department

THE OLD COURT HOUSE

Block 19, Building 3

- ARCHITECT

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 34, 35

- Blanton, Wyndham B. Mention of his book, "Medicine in Virginia...,"

- 10a, 10b, 34

- Brickwork

- 17-20

- Building Histories of Carpenter's Hall, Hospital and Old Court House Compared

- 15, 16

- Bulkhead

- 19, 24

- CAPITOL

- Carpenter's Hall, Philadelphia Building history of

- 15, 16

- Carter's Grove

-

- Stone steps of

- 21

- Chambers, Sir William, Civil Architecture

- 13

- Charles, John S. Recollections

- 20, 34

- Chimney cap illustrated

- 19

- Chimneys

- 19

- Circle Club

- 3

- Coke-Garrett House

-

- Porch of

- 23

- College of William & Mary

- Columns

- Constitutional Convention Meets in Carpenter's Hall

- 10, 16

- Court House on Market Square

- See Old Court House

- Court House on Palace Green

-

- Sale of

- 1

- Cranston, L. J.

-

- Water color drawing by, showing Old Court House

- 7

- Cupola

- DATES of restoration

- Title page

- Dating of a building

- 32, 33

- Definitions of Terms used in Architectural Records

- 30, 31

- Doorway, described

- 25, 26

- Drawings

-

- Measured drawings and working drawings for restoration of Old Court House

- 35

- ENGLISH, student of William and Mary College, discovers fire in Old Court House

- 3

- Episcopal Seminary in Alexandria

- 2

- 37.

- Exterior of Old Court House discussed in detail

- 17-27

- Exterior view

- Frontispiece

- FARISH, Dr. Hunter D.

-

- Research Report written by

- Title page, 34

- Fauquier, Governor Francis Williamsburg Recommends establishment of a hospital for the insane

- 15

- Fire in Old Court House

- 3, 4, 16

- First Continental Congress Meets in Carpenter's Hall

- 10, 15

- Frenchman's Map

- 35

- GENERAL Assembly

-

- Appoints trustees for the Hospital

- 15

- "Germantown Doorway"

- 7

- Glossary of Architectural Records Department

- 35

- Gloucester Court House

- Goodwin, Dr. W. A. R.

-

- Plan of, to restore Williamsburg

- 5

- Goodwin, Rutherfoord A Brief and True Report Concerning Williamsburg

- 34

- Governor's Palace

- Gutters of brick

- 20

- HOODS

- Hospital for the Insane

- "Hustings" court

- 1

- INTERIOR of Restored Court House

- 28

- JAMES City County

- Jefferson, Thomas

- Johnson House, Philadelphia

- 7

- Johnston, W. C., Editor of Virginia Gazette

- 3

- Journal of House of Burgesses

- KENDREW, A. Edwin, Chief Draftsman

- Title page

- MACOMBER, Walter M., Resident Architect

- Title page

- Measured drawings

- 35

- Moorehead, Singleton P.

-

- Working drawings made by

- Title page

- Morris, Robert

- NELSON, William, President of Council

- OLD Court House

-

- Agreement of County & City to erect a court house

- 1, 2, 15

- Auctions held before

- 3

- Becomes a museum

- 5

- Brickwork

- 17-20

- Bulkhead

- 19, 24

- Chimney cap, illustrated

- 19

- Chimneys

- 19

- Completion date, 1772

- 3

- Cupola

- 26, 27

- Doorway

- 25, 26

- Doric columns installed

- 4, 7

- 38.

- Elevation of

- Exterior of, discussed in detail

- 17-27

- Fire of 1911 in

- 3, 4, 16

- Foundations

- 19

- Hearths

- 20

- Interior discussed

- 28

- Life history of

- 3-5

- Measured drawings of

- 35

- Pediment

- 23, 24

- Photograph of, in 1870s

- 7, 34

- Plan exhibited at Mr. Hays

- 1

- Plan of

- Question as to who its architect was

- 8-12

- Restoration of 1911

- 4

- Restoration of 1932

- 5, 16

- Roof

- 21, 22

- Shutters

- 27

- Site of, on Market Square

- 2

- Specifications for restoration of

- 35

- Stone masonry

- 20

- Trim, exterior

- 23

- Used as barrack

- 3

- View of, after restoration of 1911

- 4

- Walls, exterior & interior

- 22

- Water table

- 19

- Windows

- 24, 25

- Working drawings for restoration of

- 35

- PAIN, William, author of The Builders Companion

- 8

- Palladio, Andrea

-

- Opinion on proportions of windows

- 13

- Pediment,

- Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, architects

- Title page

- Photographs of Old Court House

-

- At present

- Frontispiece, 34

- In 1870s

- 7, 34

- Pillars,

- see "Columns"

- Plan of Old Court House

- Proportioning of facades

- 8

- Rules followed in Old Court House design

- 8, 12-14

- Rules for, in eighteenth century handbooks

- 8

- Presidents House of College of William and Mary, Hood of, over north doorway

- 6

- Provincial Assembly

- Public Magazine

- 4

- Purdie and Dixon, Editors of Virginia Gazette

- 1

- RIND, Editor of Virginia Gazette

- 1

- Rockefeller, John D., Jr.

-

- Makes possible restoration of Williamsburg

- 5

- Roof covering

- 22

- Roof, described

- 21, 22

- SHUTTERS

- 27

- Site of Old Court House on Market Square

- 2

- Smith, Robert

- Specifications for Old Court House restoration

- 35

- Stone steps

- 39.

- Stone steps for Old Court House Described

- 20, 21

- Swan, Abraham, author of Designs in Architecture

- 8

- Swem, E. G. Virginia Historical Index

- 34

- TALIAFERRO, Richard

-

- Named by Waterman as possible architect of Old Court House

- 8

- Trim, exterior

- Trudell, Clyde F.

-

- Architectural Report by

- Title Page, 17, 34

- Working drawings made by

- Title page

- Tuckahoe, Goochland County

-

- Hood over west doorway

- 6

- Tyler, Lyon G. Williamsburg, The Old Colonial Capital

- 34

- VESTRY Book of Stratton Major Parish

- 5, 6, 34

- Virginia Gazette

- WALLS, exterior and interior

- 22

- Ware, William Rotch Editor of The Georgian Period

- 34

- Waterman, Thomas Tileston

- Water table

- 19

- William and Mary Quarterly

- 2, 34

- Windows, described

- 24, 25

- Wise, Herbert C, and H.F. Beidleman, Authors of Colonial Architecture for Those About to Build

- 34

- Working drawings for Old Court House

- 35

- Wren Building of College of William and Mary

-

- Jefferson's plan for completion of quadrangle of

- 9

- Wren, Sir Christopher Credited with design of Old Court House

- 8

INDEX

ADDENDA

Architectural Report on the Old Court House of 1770, Block 19

Harwood's Ledger of 1777 contains entries that show that changes were made to the old Court House on that date, including the "whitewashing of the court room;" "cutting away Chimney & Working in 2 new grates;" "Whitewashing 3 jury rooms." An item "lathing and nails" appears, from its small cost, to have been for repairs, following "cutting away Chimney."

Evidence for and against the existence of columns on the porch front of the old Court House have been advanced, based in part on recorded statements of travelers and records of the locality. The following pro and con items were prepared for presentation by the Advisory Committee of Architects, December 9 and 10, 1931.

OLD COURT HOUSE

(Evidence concerning the use of columns under the Pediment of the Portico)

| EVIDENCE FOR | EVIDENCE AGAINST |

|---|---|

| 1. Hearsay evidence from town sources that traces of the forms of column bases were visible upon upper step or stone floor of the portico before its removal. | 1. Non-existence of views or specific description of the Court House with columns. |

| 2. Record by Aucteville, a French visitor in 1781: "One finds there a house for the Governor, a Church, a town hall and many other beautiful private residences built of brick and adjoined with wooden domes and peri-styles. A large part of the other houses are built of wood covered with wooden boards built with care, taste and cleanliness even with columns. | 2. Existence of views of the Court House without columns. |

| 3. Evident intention of the builders. | 3. The evident great strength of the frame cantilever which held the pediment in place; no sag being visible in nineteenth century views. Thus construction infers the non-existence of the columns at the actual time of construction and the provision of a measure to complete the building in anticipation of their arrival. |

The Advisory Committee of Architects was urged by Mr. Kenneth Chorley, December 10, 1931, to give an opinion on the desirability for adding the columns as support to the old Court House porch pediment.

The response of the Advisory Committee was that evidence, as quoted above, appeared to point to the omission of columns from the time when the building was completed. It was felt that the omission followed inability to secure columns ordered either in England or from some local source. While the hospital, completed at almost the same date, had columns, such a feature was by no means won. The phrase "even with columns," mentioned under Item 2 of the compiled listing of evidence, is indication of this uncommon character. Handbooks of mid-century England mention designs [James Gibb's Book of Architecture, 1728] "of use to such Gentlemen as might be concerned in Building, especially in the remote parts of the Country, where little or no assistance for Designs can be procured. Such may be here furnished with Draughts of useful and convenient Buildings and proper Ornaments; which may be executed by any Workman who understands Lines, either as here Designed, or with some alteration ...."

Without supporting columns, the projecting pediment, while serving as a porch roof, is hardly structural. It is of interest to contemplate on the influence of such an unsupported pediment in Williamsburg. Were the porch pediments over the doorway of the Peyton Randolph House and of the President's Horse doorway at the college late additions that reflect the old Court House pediment, or were these lesser pediments early and did they influence the design of the unsupported Court House porch?