Reconsidered Splendor: The Palace Addition of 1751 Architectural Report Block 20 Building 3Reconsidered Splendor: The Palace Addition of 1751 - A Report to the Program Planning and Review Committee

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0149

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

RECONSIDERED SPLENDOR:

THE PALACE ADDITION OF 1751

A Report to the Program Planning and Review Committee

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Abstract

The following analysis is a response to a request from the Program Planning and Review Committee concerning possible changes to the supper room in the Governor's Palace. It reviews the evidence for the 1931-35 reconstruction and offers new thoughts on the character of the two rooms in the 1751 addition. After summarizing the results of fieldwork in America and limited research on British buildings, it suggests that the relationship of the two rooms is a crucial concern. Problems with both rooms are examined and alternative designs are suggested. These designs are described in some detail in order to acquaint the committee with the degree of change that would be necessary to bring the rooms into concurrence with similar suites of rooms constructed in the eighteenth century. Finally, the importance of the present reconstruction is proffered, and several options are briefly placed in context.

For further background, this report can be read in conjunction with a description of the houses visited in the course of the research.

The Reconstructed Wing

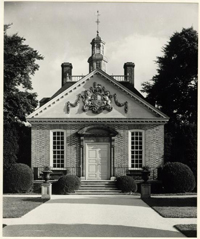

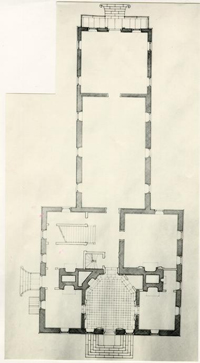

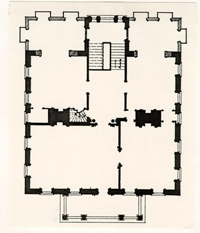

When the Governor's Palace was reconstructed in 1931-35, relatively little was known about the form and architectural finish of the circa 1751 rear wing (figs. 1 and 2). The general arrangement and room dimensions (approximately 26 feet by 47 feet for the ballroom, 26 feet square for the supper room) were available from archaeology and from a plan drawn by Thomas Jefferson, as well as window placement from Jefferson's plan.1 Functions were implied by the names used and the furnishings listed in Lord Botetourt's inventory of 1770. The absence of chimney foundations and the presence of "1 large dutch stove" in both rooms, according to the inventory, indicated the lack

Fig. 1. The Governor's Palace, as reconstructed. Plan by Singleton P. Moorehead, from Marcus Whiffen, The Public Buildings of Williamsburg.

Fig. 1. The Governor's Palace, as reconstructed. Plan by Singleton P. Moorehead, from Marcus Whiffen, The Public Buildings of Williamsburg.

Fig. 2. Plan of the Governor's Palace, drawn by Thomas Jefferson.

5

of fireplaces.2 Robert Beverley's April, 1771 note to Samuel Athawes and the Botetourt records of payment to Joseph Kidd for mending paper in the ballroom in 1769 and 1770 established that the large room had blue wallpaper with gilt borders.3 The 1770 inventory indicated that paper with gilt borders was also intended for the supper room, but that the paper and its foundation cloth had not been installed at the time of Botetourt's death.4 Further, the inventory noted the presence of '8 stockoe Brackets" (apparently to carry candelabra) and three glass 6-branch "lustres" in the ballroom and a glass 12-branch "lustre" in the supper room.5 The references to paper indicate that the walls were not fully paneled. Instead, they were probably finished with plaster or boarding for wallpaper between cornices and chair rails, and wainscoted below the chair rail, all in accordance with English and American taste in the third quarter of the

6

century. The inventory references to gilt borders and costly furnishing--especially the lighting devices--reinforced the impression that the rooms were intended for entertaining and appropriately well appointed.6

Fig. 2. Plan of the Governor's Palace, drawn by Thomas Jefferson.

5

of fireplaces.2 Robert Beverley's April, 1771 note to Samuel Athawes and the Botetourt records of payment to Joseph Kidd for mending paper in the ballroom in 1769 and 1770 established that the large room had blue wallpaper with gilt borders.3 The 1770 inventory indicated that paper with gilt borders was also intended for the supper room, but that the paper and its foundation cloth had not been installed at the time of Botetourt's death.4 Further, the inventory noted the presence of '8 stockoe Brackets" (apparently to carry candelabra) and three glass 6-branch "lustres" in the ballroom and a glass 12-branch "lustre" in the supper room.5 The references to paper indicate that the walls were not fully paneled. Instead, they were probably finished with plaster or boarding for wallpaper between cornices and chair rails, and wainscoted below the chair rail, all in accordance with English and American taste in the third quarter of the

6

century. The inventory references to gilt borders and costly furnishing--especially the lighting devices--reinforced the impression that the rooms were intended for entertaining and appropriately well appointed.6

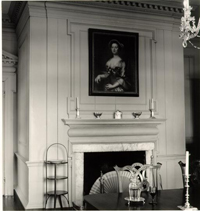

In short, there were indirect indications of costly finish in the ballroom wing, but minimal direct evidence for its interior trim or exterior elevations when Thomas Waterman and others developed plans for the reconstruction.7 As he explains in Mansions of Virginia, Waterman assumed that the ballroom "must have been one of the great rooms of the Colonial period. Even the splendor-loving Governor Tryon, who received in regal style at his Palace in New Bern, North 7 Carolina, seated with his wife on a dais in the great drawing room, could not match the magnificent setting of the functions of the Royal Governor of Virginia." Waterman further cites the presence of Allan Ramsay portraits of George III and Queen Charlotte as evidence of the room's elegance. 8

In the absence of direct evidence for the architectural finish of the two rooms,9 Waterman drew on a variety of American and British prototypes. He identifies the drawing room at the Miles Brewton House in Charleston as the chief model (fig. 3).[10] The circa 1765-69 Brewton room is somewhat comparable in size (approximately 20' by 29') and as the richest entertaining room in one of the most lavishly finished mid-century houses in the colonies, it probably has considerable relevance as an analogy to the Palace ballroom. Nevertheless, in 1931-35, it seems to have been used primarily as a model for the great coved ceiling and probably the Corinthian cornice, although Shirley is cited as the prototype. Raised-panel wainscoting with cyma moldings is attributed to

Fig. 3. Miles Brewton House, Charleston. Drawing room, with the passage door to the left. Photo, W. J. Graham, CWF.

9

the Miles Brewton House, and the windows, with panels above creating breaks in the cornice, were inspired by examples at Brooks Bank in Essex County.11 Perhaps most dominant, though, are two very large-scale doorways principally based on a late seventeenth-century Welsh prototype previously recorded by Waterman at Tredegar Park.12 The moldings and carving of the doors themselves were related to William Buckland's work at Gunston Hall.

Fig. 3. Miles Brewton House, Charleston. Drawing room, with the passage door to the left. Photo, W. J. Graham, CWF.

9

the Miles Brewton House, and the windows, with panels above creating breaks in the cornice, were inspired by examples at Brooks Bank in Essex County.11 Perhaps most dominant, though, are two very large-scale doorways principally based on a late seventeenth-century Welsh prototype previously recorded by Waterman at Tredegar Park.12 The moldings and carving of the doors themselves were related to William Buckland's work at Gunston Hall.

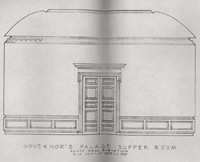

For Waterman's perspective on the supper room, it is perhaps best to quote him at some length:

The supper room is purely an assumption as far as the decorative treatment is concerned. The use of the so-called Chinese Chippendale style was based on its vogue at this time in England, and its dissemination through architectural publications took it to the farthest parts of the English Colonies. The Carolina Gazette for April 1, 1757, notes for sale the Reid house "new-built . . . after the Chinese taste." As exemplified by the supper room, there was little actual Chinese ornament in the architectural decoration of rooms in this style. Rather richly carved trim with baroque touches was given an oriental cast by, perhaps, a single motive. In the Chinese Chippendale style the Oriental effect is achieved by the use of concave pediments above the doorways, recalling the curved roofs of pagodas. In Badminton, the vast house of the Duke of Beaufort, kinsman of Lord Botetourt, next to last and most beloved of Virginia's Colonial governors, concave 10 pediments are used in the drawing room. The single Chinese note of the supper room is made dominant by the superb, eighteenth-century single paper, painted for an English house in China in the eighteenth century. This is in grisaille, against a soft blue ground, with birds and flowers in full color.

In form, the supper room is twenty-six feet square, with a coved ceiling eighteen feet high, similar to that in the ball room. Great walnut double doors of fine craftsmanship lead into the room in the south wall, and opposite matching doors lead to the magnificent garden. This relationship to the grounds makes especially happy the floral quality of the supper room.13

Waterman was unquestionably a skillful designer, and his general compositions for both rooms are visually coherent despite their diverse sources (figs. 4, 5 and 6). The supper room design was particularly successful, sufficiently so to exert an influence on several generations of popular American taste. The question posed by the Program Planning Committee was not, however, how coherent or pleasing the design of the supper room is, but rather whether it is a believable approximation of its eighteenth-century predecessor.

Fig. 4. Governor's Palace ballroom, looking towards the supper room. Photo, Hans E. Lorenz, CWF.

Fig. 4. Governor's Palace ballroom, looking towards the supper room. Photo, Hans E. Lorenz, CWF.

Fig. 5. Governor's Palace supper room, looking east. Photo, Hans E. Lorenz CWF.

Fig. 5. Governor's Palace supper room, looking east. Photo, Hans E. Lorenz CWF.

Fig. 6. Governor's Palace supper room, looking toward the ballroom. Photo, Hans E. Lorenz, CWF.

Fig. 6. Governor's Palace supper room, looking toward the ballroom. Photo, Hans E. Lorenz, CWF.

Rooms for Entertainment

Despite substantial discoveries concerning the Palace made over the past fifty years, there remains essentially no new information that can provide direct evidence for the room's architectural character. On the other hand, thinking about how buildings work and the processes by which they were designed has evolved, and new perspectives may provide new clues. Colonial Revival architects and architectural historians of the early twentieth century recognized variations in style and relative scale or costliness. Yet it can be argued that their design process was much more concerned with matters of accuracy in detail and cohesiveness of composition--what might be called good design--than with questions about the economic choices that faced the original builders. Seeing buildings as indications of past social conditions, recent architectural historians have shifted their interest toward the relationships that can be seen within and among buildings.14

With this perspective in mind, it seemed useful to look again at a series of sizable gentry houses and public buildings of the circa 1750-75 period, located in four 15 seemingly relevant southern and mid-Atlantic states.15 With relatively detailed recording and analysis, these buildings might provide two things: a better understanding of the relationship of interior trim to room arrangements in the period, and a series of related interiors that could be used as a scale by which to compare the degrees of richness used in the Palace reconstruction. There was little hope of finding rooms that were entirely analogous to the ballroom and supper room. However, we knew that we would find groups or pairs of entertaining rooms that would be of some use, and we hoped that some of these would approach the scale and presumably the level of finish of those in the ballroom wing. We were successful in both regards.

Further, there is the necessary question of British variation. Might not a major entertainment wing for a royal governor follow certain patterns not reflected in even the largest surviving American houses? Rather than attempting to pursue the question with new fieldwork in Britain, we have relied on archival research and inquiries among knowledgeable architectural historians in England.

Individual analyses will be found in an accompanying report, "Grand House Interiors of Colonial America." 16 The essential findings can be briefly summarized here. One simple point that the various descriptions should make extremely clear is that there is great variation in room finish within any one large gentry house. In decorative terms, the distance between the best public room and the plainest chamber is very great indeed. While individual or local taste may well determine certain choices in finishing or furnishing a house, those choices are made within an accepted design system, and are dependent on the perceived social value of the various spaces. Thus Robert Beverley might import costly marble mantels and stylish wallpapers for his public rooms at Blandfield, while finishing second-floor chambers in a manner that, from the perspective of an art historian, seem rather ordinary and extremely old fashioned.16 Perhaps the greatest fault of early twentieth-century reconstructions is the common failure to recognize the range of choice that existed in the period theoretically being recreated, and the connection between finish and function.

In eighteenth-century American gentry houses, superior finish was principally concentrated in entertaining 17 rooms, and, to a lesser degree and on a much more occasional basis on major chambers. At Shirley, for example, the best space is the largest river-side room--probably a parlor--and its smaller adjoining room--probably a dining room-has a simplified version of the same decorative scheme (figs. 7 and 8). As at Kenmore, where a similar pair of river-side rooms share a general scheme, the rooms are approached from a relatively plain stair hall and are directly linked to one another by a door. In both houses, there is a third fine first-floor room, without direct access to the two connected rooms. This approach to circulation is interpreted as indicating that the river-side rooms were intended for related social functions, and that the third room was intended as a principal chamber. Also in both cases, the third room is quite different in decorative scheme, but it is comparable to or even better than the smaller public room in degree of finish (figs. 9 and 10).

At a relatively simple level, the examples of Shirley and Kenmore offer characteristics that seem to be shared by most American gentry houses of the late colonial period: entertaining rooms are generally approached through a passage or entrance hall, these rooms are often paired, and, when paired, they are always directly linked to one another by a doorway. More to the point of the question

Fig. 7. Shirley, Charles City County, Virginia. Parlor mantel. Photo, E. A. Chappell, CWF.

Fig. 7. Shirley, Charles City County, Virginia. Parlor mantel. Photo, E. A. Chappell, CWF.

Fig. 8. Shirley. Dining room mantel. Photo, W. J. Graham, CWF.

Fig. 8. Shirley. Dining room mantel. Photo, W. J. Graham, CWF.

Fig. 9. Kenmore, Fredericksburg, Virginia. Drawing room, circa 1930. Photo, Metropolitan Engraving Company, Richmond.

Fig. 9. Kenmore, Fredericksburg, Virginia. Drawing room, circa 1930. Photo, Metropolitan Engraving Company, Richmond.

Fig. 10. Kenmore. First-floor chamber, circa 1930. Photo, Metropolitan Engraving Company, Richmond.

22

at hand, the larger of the entertaining rooms is virtually always the most carefully and expensively finished and the smaller entertaining room is given secondary status. At Shirley and Kenmore, the smaller room's hierarchical relationship with the first-floor chamber is rather ambiguous; but within a similar system at the Ridout House in Annapolis, the smaller room (again probably a dining room) is clearly treated as inferior to a rather grand first-floor room that would seem to be a chamber.

Fig. 10. Kenmore. First-floor chamber, circa 1930. Photo, Metropolitan Engraving Company, Richmond.

22

at hand, the larger of the entertaining rooms is virtually always the most carefully and expensively finished and the smaller entertaining room is given secondary status. At Shirley and Kenmore, the smaller room's hierarchical relationship with the first-floor chamber is rather ambiguous; but within a similar system at the Ridout House in Annapolis, the smaller room (again probably a dining room) is clearly treated as inferior to a rather grand first-floor room that would seem to be a chamber.

At the Hammond-Harwood House in Annapolis, entertaining rooms are paired on the rear side of both floors, and simple chambers flank a passage at the front. On the first floor, one enters the larger room directly from the passage, while the inner room can only be reached through this room or the stair passage, not directly from the main passage. Predictably, the larger room is finished with superior woodwork. Essentially the same plan and decorative relationships are found on the second floor, but there one is demonstrably intended to pass through the smaller room before arriving in the principal space. Upon arriving, one finds that the finish is very similar to but slightly plainer than that in the major room below.

Among the buildings studied., a group of late colonial houses in Charleston seem particularly relevant 23 to the question of the Palace ballroom wing. In four cases ranging from the relatively modest David Ramsay House to the exceptionally grand Miles Brewton House, there are pairs of second-floor entertaining rooms that begin to approach the ballroom and supper room in scale and proportion.

As at the Palace, these rooms constitute pairs of specialized entertaining spaces that seem to have existed in addition to a more traditional or at least more normal first-floor parlor and dining room. At the Palace, the ballroom and supper room were additions housed in a rear ell. In the Charleston houses, the two rooms were original features incorporated into the second stories of otherwise conventional Georgian plans (fig. 11). The finish of the Charleston rooms represents range of taste and degree of elaboration, but there are clear hierarchical patterns shared by each example. Consistently, the larger room (now generally referred to as a drawing room) is treated as the superior space in the house.17 The smaller room receives a level of elaboration that expresses its role as a setting for gentry

Fig. 11. Miles Brewton House. Second-floor plan, from Albert Simons and Samuel Lapham, The Early Architecture of Charlston.

25

social interaction, but the finish is always significantly less costly than that of its mate. Moreover, it is generally less expensively finished than the first-floor parlor (figs. 12 and 13).

Fig. 11. Miles Brewton House. Second-floor plan, from Albert Simons and Samuel Lapham, The Early Architecture of Charlston.

25

social interaction, but the finish is always significantly less costly than that of its mate. Moreover, it is generally less expensively finished than the first-floor parlor (figs. 12 and 13).

Reading the evidence of circulation systems and room finish, one can suggest a pattern for entertaining in the Charleston houses. The best first-floor room was used as a parlor, much like the front right room at the Palace. Either to one side or behind the parlor was a dining room, well finished but markedly inferior to the parlor. Presumably both could be used for public entertaining, as well as private gatherings. However, grander urban entertaining called for a further removal from the street, to the second floor in Philadelphia, to the garden side in Annapolis, and to the garden wing at the Palace. In Charleston, guests were led through a series of well-finished spaces to the superior room in the house, a long "drawing room" on the street front of the upper floor. At the Miles Brewton House, the room was distinguished by rich classical details, a polychrome marble mantel, and a great coved ceiling--as well as, apparently, costly blue paper with gilt borders. This room was the setting for the household's principal public social activities, whether they involved eating, dancing, or agreeable conversation. At some point in these social events, participants circulated into and back out of

Fig. 12. Miles Brewton House. Small second-floor entertaining room. Photo, W. J. Graham, CWF.

Fig. 12. Miles Brewton House. Small second-floor entertaining room. Photo, W. J. Graham, CWF.

Fig. 13. Miles Brewton House parlor. Photo, W. J. Graham, CWF.

28

the inner "withdrawing room." Whether the subsidiary room was used for cards and refreshments (perhaps like the supper room at the Palace) or as a space in which to segregate men or women (following familiar English practice) is not known at this point.18 Whatever the particular use, the variation in finish makes it clear that the smaller room was viewed as secondary, and the circulation system in some houses shows that it was treated as an inner room rather than as one stop on a circuit. Guests reentered the larger room before exiting to the second-floor passage.

Fig. 13. Miles Brewton House parlor. Photo, W. J. Graham, CWF.

28

the inner "withdrawing room." Whether the subsidiary room was used for cards and refreshments (perhaps like the supper room at the Palace) or as a space in which to segregate men or women (following familiar English practice) is not known at this point.18 Whatever the particular use, the variation in finish makes it clear that the smaller room was viewed as secondary, and the circulation system in some houses shows that it was treated as an inner room rather than as one stop on a circuit. Guests reentered the larger room before exiting to the second-floor passage.

Ballrooms and Assembly Rooms

The Charleston houses offer certain room relationships that appear to be remarkably close to those at the Palace They reinforce the general impression that larger rooms such as the ballroom were treated as superior to associated smaller rooms like the supper room. 19 This is, of course, essentially the opposite of the circumstances at the Palace, where the supper room is treated as a distinctly superior space, perhaps somewhat like an inner room of pre-eighteenth century state apartments in great European country houses. 20 The possibility that the ballroom wing might follow the old state apartment model, with the governor creating an inner sanctum beyond the 30 ballroom seems extremely remote, but it is a question we raised with a number of English scholars, and through archival research. The results were limited, but they reinforced our skepticism about the present conditions.

State apartments did continue to be included in grand British houses built in the eighteenth century, but there is no apparent evidence that they dictated the relationship of other room pairings. Within groups of physically related entertaining rooms, the larger rooms appear to maintain preeminence. Yet again we have to rely primarily on drawing rooms and saloons, as we have no strict analogies. 21

Regrettably, the chief country house parallel that has been proposed is highly problematic. Hopetoun, a grand house in West Lothian near Edinburgh has in one of its wings an oversized rectangular room that has been identified as a ballroom (fig. 14). Typically, complexity in the development of the house makes comparison of the room finish a thorny issue, but the purported ballroom is unquestionably plainer than two surviving rooms in a suite of state apartments.22

Fig. 14. Hopetoun House, West Lothian, Scotland, largely by William Adam. Plan by Thomas Rose and Fred McGibbon, from Charles H. Wood, ed., Hopetoun House.

Fig. 14. Hopetoun House, West Lothian, Scotland, largely by William Adam. Plan by Thomas Rose and Fred McGibbon, from Charles H. Wood, ed., Hopetoun House.

While the state dining room and saloon are finished in a lavish mid eighteenth-century style, the room in the wing is a slightly earlier and somewhat elaborated version of what one can envision for the Palace ballroom (fig. 15).23

Fig. 15. Hopetoun House ballroom or library. Photo from Wood.

34

Both the specific finish of the room and its relationship to the rest of the house make this an enticing precedent for our purposes, but its relevance is made suspect by an early identification as a library rather than a ballroom. 24

Fig. 15. Hopetoun House ballroom or library. Photo from Wood.

34

Both the specific finish of the room and its relationship to the rest of the house make this an enticing precedent for our purposes, but its relevance is made suspect by an early identification as a library rather than a ballroom. 24

Whatever its original function, the Hopetoun room does not negate the relevance of American patterns of room finish to the Palace. At Hopetoun, the ballroom wing is an extremely specialized area substantially removed from the principal entertaining rooms. 25 While the room itself can be usefully compared to the ballroom at the Palace, there was nothing equivalent to genuine state apartments at the Palace. 26

35The Palace ballroom wing seems more related to the group of large entertaining rooms incorporated into the main block of American houses already discussed and, perhaps more pointedly, to superior rooms added to other Virginia houses in the second half of the eighteenth century. 27 The fashion for larger-scale entertainment and the rooms that could accommodate it was not confined to the colonies. Isaac Ware observed the trend in England with less than satisfaction:

The custom of routs (assemblies) has introduced this absurd practice. Our forefathers were pleased with seeing their friends as they chanced to come, and with entertaining them when they were there. The present custom is to see them all at once, and entertain none of them; this brings in the necessity of a great room which is opened only on such occasions, and which lords and generally discredits the rest of the edifice . . . .2836

The Palace wing was unusually large for its locality, perhaps with a closer resemblance to the rooms Ware remarked on than with anything one might have seen in a private American house. In size and form as well as function, the ballroom and supper room bear similarities to provincial assembly rooms, institutions that are less elusive than country house ballrooms. Architectural historian Mark Girouard agrees that English assembly rooms may offer a more relevant analogy than drawing rooms because of the former's scale and the proximity to smaller withdrawing rooms. On the latter subject, he suggests:

Most of these had a Great Room and one or two smaller rooms off it. In Assembly Rooms, the Great Room was normally used for dancing and the smaller rooms were usually a Card Room and a Tea Room for refreshments. Supper was not normally served in Assembly Rooms, but there is an obvious analogy with your two rooms in the Palace at Williamsburg. I can't think of any examples where the smaller rooms were more richly decorated than the large one. At York, the Big Room is much the most magnificent, at Bath the three rooms have a fairly constant level of splendour.29

As a principal component in the growth of structured public entertainment in Georgian Britain, assembly rooms represented an entirely new building type. 30 The most 37 famous among these is the 1731-2 York Assembly Rooms referred to by Girouard. It was designed by Palladian leader Lord Burlington to house a long rectangular room with Corinthian columns supporting a clerestory, thus providing light for the two-story space as well as a requisite sense of grandeur. The great room is flanked by a series of smaller inner rooms which seem to have been entered rather ceremoniously through wide trabeated wall openings midway along the colonnades (fig. 16).31 Through a less grand and more circuitous route, they could also be reached from a vestibule at the front of the great room.

That such rooms had a functional and a spatial relationship to the Palace addition is made clearer by a 1797 plan of Robert and James Adams' Glasgow Assembly Rooms in

Fig. 16. The Assembly Rooms at York, by Lord Burlington. Plan by Henry Flitcroft, from John Harris, The Palladians.

39

Richardson's Vitruvius Britannicus (fig. 17).32 There the principal room, placed at the front of the upper floor, is called a "Ball Room or Concert Room." The symmetrical space is lighted by a large Palladian facade window, which is elaborated as a decorative feature intended to be seen when entering the room. The room measures 34 by 70 feet and has an apse at each end.33 It is reached by passing through an impressive series of spaces reminiscent of the route to the Miles Brewton drawing room. One enters a ground-floor hall and proceeds through a lobby to the principal stair. After ascending the stair, the visitor passes from a domed vestibule through a doorway framed by pilasters into the ballroom. Behind the ballroom are two smaller asymmetrical rooms, called "Supper Room or Card Room" and "Dancing Room or Card Room" respectively. They flank the stair hall and vestibule, and are accessible from these two spaces as well as from the

Fig. 16. The Assembly Rooms at York, by Lord Burlington. Plan by Henry Flitcroft, from John Harris, The Palladians.

39

Richardson's Vitruvius Britannicus (fig. 17).32 There the principal room, placed at the front of the upper floor, is called a "Ball Room or Concert Room." The symmetrical space is lighted by a large Palladian facade window, which is elaborated as a decorative feature intended to be seen when entering the room. The room measures 34 by 70 feet and has an apse at each end.33 It is reached by passing through an impressive series of spaces reminiscent of the route to the Miles Brewton drawing room. One enters a ground-floor hall and proceeds through a lobby to the principal stair. After ascending the stair, the visitor passes from a domed vestibule through a doorway framed by pilasters into the ballroom. Behind the ballroom are two smaller asymmetrical rooms, called "Supper Room or Card Room" and "Dancing Room or Card Room" respectively. They flank the stair hall and vestibule, and are accessible from these two spaces as well as from the

Fig. 17. The Assembly Rooms at Glasgow, by Robert and James Adam. Ground and upper floor plans. From George Richardson, The New Vitruvius Britannicus.

41

ballroom. 34 Our information about their finish is limited to the plan, but their unbalanced shapes and somewhat extraneous position establishes them as subordinate to the ballroom.

Fig. 17. The Assembly Rooms at Glasgow, by Robert and James Adam. Ground and upper floor plans. From George Richardson, The New Vitruvius Britannicus.

41

ballroom. 34 Our information about their finish is limited to the plan, but their unbalanced shapes and somewhat extraneous position establishes them as subordinate to the ballroom.

Assembly rooms could stand alone, as in the examples just cited, or could be incorporated into a civic building also housing courtrooms, meeting rooms, or a market. Most of these functions were combined with a ballroom in a complex building constructed at Newark in Nottinghamshire about 1776 by John Carr of York. Again, the principal room (now called a ballroom but labeled as an "Assembly Room" in Richardson's Vitruvius Britannicus) is long (30 by 80 feet) and richly elaborated. Pairs of freestanding columns screen an apse at each end, pilasters extend around the walls, and the ceiling is about 30 feet high. Not surprisingly, the room is superior in finish to all other rooms, including a withdrawing room. 35

Some American towns provided special accommodations for routs, and at least two Chesapeake examples had attendant 42 rooms. In Fredericksburg, a two-story market house contained sizable assembly rooms. The institution was commented on in 1777 by an ideological descendent of Isaac Ware:

May 26, 1777 At Fredericksburgh. Even this small Town affords a Proof of the Luxury & Extravagance of its Inhabitants, for a House has been erected by private subscription, which is entirely devoted to Dissipation. It is of Brick (not elegant) & contains a Room for Dancing & two for retirement & Cards.36The proper setting for public dissipation meant enough to forty affluent citizens that they subscribed £235 for the building's repair in 1782. 37

The Fredericksburg assembly rooms may have been "not elegant," but their counterpart on the second floor of the 43 1767 Chowan County Courthouse in Edenton, North Carolina is perhaps the most impressive eighteenth-century space in the state (fig. 18). The principal Edenton room measures 30 feet by 45 feet and is 13 feet high. It has the exceptional features of a pair of opposed fireplaces and full-height paneling with an Ionic entablature. The finish of two small flanking rooms is unknown.38

Several surprisingly helpful references inform us that eighteenth-century Virginians followed the general pattern of British assemblies in as much as they were accustomed to dance first and later, at acceptable points in the evening, withdraw to other rooms for refreshments. Specialized ballrooms and supper rooms were not necessarily required. In February, 1711, prior to completion of the Palace, Alexander Spotswood held a ball at the Capitol. Following an hour of country dances, "the company was carried into another room where was a very fine collation of sweetmeats." 39 At later

Fig. 18. Chowan County Courthouse, Edenton, North Carolina, 1767. Second-floor assembly room. Photo, W. J. Graham, CWF.

45

weekly assemblies sponsored by Spotswood, supper was served when dancing stopped at ten o'clock; thereafter dancing continued until two.40 In 1740, veteran router William Byrd attended a ball held by James Blair at the Capitol and left at an early hour after eating three jellies.41 A particularly elaborate assembly was held at the Capitol in 1746 to celebrate the victory of the Duke of Cumberland at Culloden:

Fig. 18. Chowan County Courthouse, Edenton, North Carolina, 1767. Second-floor assembly room. Photo, W. J. Graham, CWF.

45

weekly assemblies sponsored by Spotswood, supper was served when dancing stopped at ten o'clock; thereafter dancing continued until two.40 In 1740, veteran router William Byrd attended a ball held by James Blair at the Capitol and left at an early hour after eating three jellies.41 A particularly elaborate assembly was held at the Capitol in 1746 to celebrate the victory of the Duke of Cumberland at Culloden:

In the Evening, a very numerous Company of Gentlemen and Ladies appear'd at the Capitol, where a Ball was open'd and after dancing some Time, withdrew to Supper, there being a very handsome Collation spread on three Tables, in three different Rooms, consisting of near 100 Dishes, after the most delicate Taste. There was also provided a great Variety of the choicest and best Liquors, in which the Healths of the King, the Prince and Princess Of Wales, the Duke . . . were chearfully drank.42The most intimate view of the changing scenes that one could encounter at a Virginia ball is provided by diarist Philip Fithian. In January, 1774, the disapproving Presbyterian described his experience at a gathering at Richard Lee's "Lee Hall" in Westmoreland County:

I was introduced into a small Room where a number of Gentlemen were playing Cards, (the first game I have seen since I left Home) to 46 lay off my Boots Riding-Coat&c--Next I was directed into the Dining-Room to see Young Mr Lee; He introduced me to his Father--With them I conversed til Dinner, which came in at half after four. The Ladies dined first, when some Good order was preserved; when they rose, each nimblest Fellow dined first--The Dinner was as elegant as could be well expected when so great an Assembly were to be kept for so long a time . . . About Seven the Ladies & Gentlemen begun to dance in the Ball-Room--first Minuets one Round; Second Giggs; third Reels; And last of All Country-Dances; tho' they struck several Marches occasionally--The Music was a French-Horn and two Violins--The Ladies were Dressed Gay, and splendid, & when dancing, their Silks & Brocades rustled and trailed behind them!--But all did not join in the Dance for there were parties in Rooms made up, some at Cards; Some drinking for Pleasure; some toasting the Sons of america; some singing "Liberty Songs" as they call'd them.43Although it appears that Virginians may have brought more realism to the term rout than their York and Glasgow counterparts, some of the variety may be due to social differences. The ballroom wing at the Palace probably housed the closest Virginia equivalent to a Beau Nash performance. Elsewhere, taverns and houses provided less formal venues for related social behavior. 44

A Fragment of Masonry

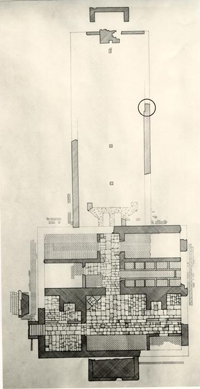

One additional piece of physical evidence should not be overlooked. In several recent letters, J. T. Smith at the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England) pointed to an archaeological feature possibly indicating that the two Palace rooms were treated differently from one another (fig. 19).45 Near the junction of the ballroom and supper room, the fragmentary foundation walls changed in thickness from 2' 5" (on the south) to 2' (on the north). Smith suggests that this could indicate either that the two rooms were built at different dates or that the walls of the supper room were lower than those of the ballroom and, hence, required less substantial footings. Rather poor photographs of the excavations seem to show the two walls bonded together; consequently, the likelihood of there being two stages of construction seems remote. 46 There are also other potential explanations for the variation, none particularly convincing. It is possible for example, that the thicker walls were intended to carry additional structure for a coved ceiling in the ballroom and not in the supper room, although eighteenth-century coved ceilings generally are not framed in such a way as to require additional

Fig. 19. Palace Foundations. Plan by Singleton P. Moorehead, from Whiffen, Public Buildings. Note circled area.

50

support. The shift in wall thickness might also be the result of change during construction. Somewhat similar mid-construction changes were made to the foundation walls at Carter's Grove and Blandfield. Alternately, the shift in thickness could conceivably represent a desire to make the window reveals more monumental in the ballroom. While this seems a costly and unlikely solution, it is essentially the answer accepted by the earlier architects. Finally it is possible that part of the northern end of the wall was simply robbed away after demolition of the building, and that the fragmentary nature of the remains prevented the archaeologists from recognizing this. Smith's observation is nonetheless useful because it points out both a possible indication of room variation, for whatever reason, and it reminds us of the fact that virtually nothing is known about the elevations of the circa 1751 addition.

Fig. 19. Palace Foundations. Plan by Singleton P. Moorehead, from Whiffen, Public Buildings. Note circled area.

50

support. The shift in wall thickness might also be the result of change during construction. Somewhat similar mid-construction changes were made to the foundation walls at Carter's Grove and Blandfield. Alternately, the shift in thickness could conceivably represent a desire to make the window reveals more monumental in the ballroom. While this seems a costly and unlikely solution, it is essentially the answer accepted by the earlier architects. Finally it is possible that part of the northern end of the wall was simply robbed away after demolition of the building, and that the fragmentary nature of the remains prevented the archaeologists from recognizing this. Smith's observation is nonetheless useful because it points out both a possible indication of room variation, for whatever reason, and it reminds us of the fact that virtually nothing is known about the elevations of the circa 1751 addition.

A Critique

So, in the light of various evidence from Britain and America, how can we judge the present interior of the ballroom wing? Waterman was arguably correct in suggesting that the woodwork was probably in the grand style. We have seen that costly finish was lavished on large entertaining rooms of the period, and the new wing at the Palace seems a likely subject for conspicuous consumption. The building was the official residence of the Virginia governors, and the ballroom was perhaps larger than any other room in a colonial American house.47

Yet it should be evident by now that there is less of a problem with the level of finish than with the relative degrees of finish in the two rooms. Simply put, the decorative focus seems to be misplaced on the smaller rather than the larger room. Waterman and contemporaries did not write about those relationships, so the reason for the apparent problem is not immediately clear. However, examination of the drawings reveals that major shifts in thinking took place during the design process. The changes may reflect administrative concern for cost rather than visual experimentation. Both rooms in the wing lost some elaboration, but 52 the greatest changes were in the ballroom. Waterman's plans for the supper room may have survived relatively intact because of the considerable interest in the Chinese wallpaper, and the perceived implications the paper had for associated woodwork. Whatever the reason, the chief features to be affected were window details and plaster ceiling embellishments. In drawings dated February 6, 1931, the windows were topped with rather fanciful scrolled pediments and Rococo shellwork, octagonal shutter panels were enriched with carved rosettes, and the architraves were flanked by richly carved consoles.48 The window pediments were actually a very improbable design for an eighteenth century American building, and by November 25, they had been removed. A finished drawing of that date shows the pediments omitted, the shutter panels shorn of their carving, and the consoles 53 simplified in detail 49 Interestingly though, a nearly identical drawing of June 21, 1932 included alternative schemes for a rich group of plaster embellishments in the corners of the coved ceiling.50 Although considerably altered in design, they were based on Rococo masks in the corners of the coved ceiling of the principal room at Whitehall in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, one of the two coved ceilings cited as precedent for those in the supper room and ballroom.51 Whether or not Waterman was the initiator of the scheme is unknown, but by July, 1932, William Perry and Walter Macomber had agreed that the plaster embellishments were unnecessary.52

Waterman's plans for the ballroom sustained more radical surgery. Drawings dated February 2, 1931 show a 54 monumental design, with full-height Corinthian pilasters framing the windows.53 The window architraves are carved, and they break up into flat friezes above the windows to form a frame for additional carving. The familiar Corinthian cornice grows into entablature fragments over the openings, and the additional space above the doors is finished with seascapes.54 Raised-panel wainscoting is used, contrasting with flush-board wainscoting in the supper room. The windows are very long (16 over 20 lights), and their recesses extend to the floor, in a grand fashion.

Another drawing, unsigned and presumably later, shows a pulvinated frieze above the windows, but no pilasters 55 or seascapes.55 This plan appears to have been largely rejected in favor of the present plan, which retains the coved ceiling, Corinthian cornice, and raised-panel wainscoting, but is otherwise changed. In the last plan, the window elevations seem to have been adjusted, and more prosaic raised-panel overwindows replaced classical frieze fragments. Perhaps to compensate for the general loss of elaboration, window seats and (most profoundly) the Tredegar Park doorways were added.56

Two general problems resulted from this design process, and they affect both rooms. First, the supper room ended up with the superior woodwork. its cornice has greater enrichment, its window architraves are carved rather than left plain, the windows have double rather than single crossettes at the top and richly carved consoles at the bottom, the shutters have octagonal rather than rectangular panels, and the chair rail is carved with a fret. Further, mid-eighteenth-century taste generally placed flush board wainscoting and window reveals open to the floor above 56 raised panel wainscoting and window seats in the scale of interior finish. Here again, the superior choices were made for the smaller room. Strangely, though, the ballroom face of the walnut doors was carved but the supper room face was not.

Second, there are several problems within the ballroom design, in addition to the issues of room relationship. Most obviously, the window architraves are rather strangely seated on a beaded ground. Precedent for this detail is unknown to us, and examination of the initial plan for the room leads one to suggest that it is an unresolved remnant of the rejected pilaster design. Further, the unusual four-part architraves were drawn from a pattern book source by William Paine,57 but there is no evidence that similar architraves were used in America. More significantly, the two great Tredegar Park doorways introduce features that are recognizably drawn from a seventeenth-century prototype. The general use of a Renaissance surround with paneled pilaster strips supporting consoles that rise past a frieze to support a cornice is not an inappropriate choice for the reconstruction of a grand eighteenth-century American room,58 57 but the heavy bolection architrave and oversized broken pediment and cartouche look distinctly more 1690 than 1751.59

In short, details of both rooms seem to create an incorrect relationship between the parts of the circa 1751 wing. The most dramatic components of this problem exist in the supper room, but the weaknesses of the ballroom design are nonetheless crucial. In addition to issues of relative finish, there are several details in the ballroom that appear to be implausible for an American building of this date.

New Designs

How then should we respond to these apparent design problems? The foregoing analysis has led us to suggest that it would be inappropriate to make changes to one room but not the other. A useful approach might be to develop a new concept for how the two rooms are likely to have been finished, and then design new interiors that reflect that perspective.

By now, it should be clear that the ballroom would be superior to the supper room. Because of its scale and social position as a principal entertaining room, the ballroom should reflect a level of richness (and cost) found in the best rooms of mid-eighteenth-century high-gentry houses. The supper room should also be well finished, but in a less developed manner.

Stylistic change is also a crucial factor. By the time of Botetourt's repapering, there was an emphasis on broad, clean surfaces and rich elaboration of small components. At mid-century, though, the best interiors were poised midway between the bold and comparatively heavy elaboration of the earlier eighteenth century and the lightness of a later--a cleaner and neater--era. Carter's Grove (circa 1751-53) and Gunston Hall (1755-58) are instructive examples. At Carter's Grove, the superior 59 rooms are distinguished with full-height pilasters and flushboard wainscoting. Yet the pilasters are set on plinths projecting from the wainscoting, rather than extending from floor to ceiling finish, as they do in earlier buildings, like Marmion in King George County and the Nelson House in Yorktown, the upper walls have raised paneling rather than a flat base for wallpaper, as at Blandfield. At Gunston, extensive use was made of plaster and wallpaper above the chair rail, and pilasters reached the main entablature only in the passage, an area which generally retained full classical articulation longer than other spaces. Sizable classical orders were also used in the so-called Palladian room, but to form tabernacles around openings rather than, as it were, to hold up the ceiling. The major Gunston rooms also have flat wainscoting, and details are more richly carved than in any other surviving eighteenth-century Virginia house. Building design responds to different personalities and purses, so there are few invariable rules. Yet there is a definable stylistic trend at mid-century that should be reflected in the two rooms at the Palace. Finally, inherent in any style is a pattern of emphasis on particular features. Through the third quarter of the century, bolder elaboration was generally expended on doorways, cornices, and mantels than 60 on windows.60 Window parts could be richly carved, and associated architraves and paneling could be manipulated, but elaborate overall design treatment such as pedimented overwindows was almost always avoided.

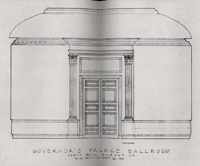

The accompanying drawings carry this concept into specific designs. The designs remain relatively hypothetical, and we have shown minor variations in order to reveal some of the deliberative process. Our preference in each case is noted. In the ballroom, the present coved ceiling and its respectably enriched Corinthian cornice would remain,61 although sections of the latter would be rebuilt in order to correspond to adjusted overwindows (fig. 20). For windows, we favor three-part architraves or

West Wall Elevation

62

conceivably four-part architraves more conventional than those now in place. Use of the former is preferable, and their presence in the large gallery at Independence Hall illustrates that they can offer sufficient bulk even for a room of this size.62 Expressing the still robust character of mid-century window surrounds, the outline of the architraves would be broken by crossettes at the head and ramps at the feet.63 The beaded grounds discussed above would be removed, the decorative wallpaper borders would be carried around the shaped architrave, emphasizing the fact that the blue paper is later in date, and perhaps in concept.64 The architraves should probably be carved, presumably with foliage on the backband and a rope molding for the inner bead.65 The sash would remain unchanged and the shutters

63

would have raised panels, without carving. Those now in place would probably be reused. Further indicating that the clean wallpaper aesthetic had not yet been fully embraced, raised-panel overwindows would also be retained, although they too would probably be slightly modified by a change in overall width. Window recesses should extend to the floor, emphasizing the relatively late date and superior status of the room, and the pedestal chair rail would be carried around the opening and treated as a windowsill. The small frieze of the chair rail might also be carved with a fret, as at Shirley and the Branford-Horry House in Charleston. It is very likely that the wainscoting would be constructed of flush boards rather than the present raised paneling, and its superior character could be established by breaking out flat plinths to carry the architrave ramps, as is shown in an eighteenth-century drawing of the principal room at Tryon's Palace in New Bern, North Carolina.66 The present baseboard

64

is a sensible, chunky, mid-century design, and it should be reused, like its mate in the supper room.

West Wall Elevation

62

conceivably four-part architraves more conventional than those now in place. Use of the former is preferable, and their presence in the large gallery at Independence Hall illustrates that they can offer sufficient bulk even for a room of this size.62 Expressing the still robust character of mid-century window surrounds, the outline of the architraves would be broken by crossettes at the head and ramps at the feet.63 The beaded grounds discussed above would be removed, the decorative wallpaper borders would be carried around the shaped architrave, emphasizing the fact that the blue paper is later in date, and perhaps in concept.64 The architraves should probably be carved, presumably with foliage on the backband and a rope molding for the inner bead.65 The sash would remain unchanged and the shutters

63

would have raised panels, without carving. Those now in place would probably be reused. Further indicating that the clean wallpaper aesthetic had not yet been fully embraced, raised-panel overwindows would also be retained, although they too would probably be slightly modified by a change in overall width. Window recesses should extend to the floor, emphasizing the relatively late date and superior status of the room, and the pedestal chair rail would be carried around the opening and treated as a windowsill. The small frieze of the chair rail might also be carved with a fret, as at Shirley and the Branford-Horry House in Charleston. It is very likely that the wainscoting would be constructed of flush boards rather than the present raised paneling, and its superior character could be established by breaking out flat plinths to carry the architrave ramps, as is shown in an eighteenth-century drawing of the principal room at Tryon's Palace in New Bern, North Carolina.66 The present baseboard

64

is a sensible, chunky, mid-century design, and it should be reused, like its mate in the supper room.

As already implied, the present doorways should probably be replaced with a relatively strong mid-century surround. Using Carter's Grove as the most specific source, we suggest using flanking pilasters set on plinths and supporting an architrave and frieze responding to the present cornice (fig. 21). Like the cornice, the pilasters would be Corinthian. The use of pilasters, particularly those with Corinthian capitals, creates an extremely difficult outline around which to carry a wallpaper border. This problem might be used as a didactic device to indicate change during the Botetourt occupancy, or it might be simply resolved by placing the classical frame on a slightly projecting field. We recognize that this solution brings us precipitously close to the existing window treatment previously criticized, but the specific application is known from English and American exterior door surrounds.67 The present walnut doors

Palace Ballroom North Wall Elevation

66

with carved moldings would be retained,68 and the architrave used for the windows would be repeated here. Crossettes would be omitted because of their relationship with the pilasters, and there would be a simple raised panel above the doors. The panels would again emphasize the relatively early date, and would correspond roughly to smaller panels above the windows.

Palace Ballroom North Wall Elevation

66

with carved moldings would be retained,68 and the architrave used for the windows would be repeated here. Crossettes would be omitted because of their relationship with the pilasters, and there would be a simple raised panel above the doors. The panels would again emphasize the relatively early date, and would correspond roughly to smaller panels above the windows.

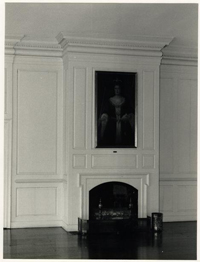

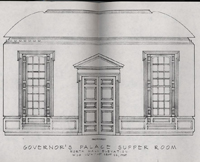

In keeping with the foregoing discussion, the supper room would be remodeled in a significantly simpler fashion than the ballroom, and a far simpler treatment than the one today (fig. 22). Again, the coved ceiling should be left, but the present rich Corinthian cornice would be replaced with an uncarved Ionic cornice. Windows and doors would have uncarved three-part architraves with crossettes only at the top. The window architraves would sit on an

Palace Supper Room North Wall Elevation

68

undecorated pedestal chair rail. Wainscoting would have raised panels, contrasting with the flush sheathing in the ballroom, and the baseboard would remain as it is.69 Shutters would have conventional joinery, with the same profile as the wainscoting unless the width of the reveals precludes the use of beveled panels. As a further contrast to conditions in the ballroom, the windows could be treated with seats, a subtle variation often used in mid-century gentry houses.70 The doorways would be distinguished only by the presence of Ionic entablatures related to the main cornice, and by simple triangular pediments.71

Palace Supper Room North Wall Elevation

68

undecorated pedestal chair rail. Wainscoting would have raised panels, contrasting with the flush sheathing in the ballroom, and the baseboard would remain as it is.69 Shutters would have conventional joinery, with the same profile as the wainscoting unless the width of the reveals precludes the use of beveled panels. As a further contrast to conditions in the ballroom, the windows could be treated with seats, a subtle variation often used in mid-century gentry houses.70 The doorways would be distinguished only by the presence of Ionic entablatures related to the main cornice, and by simple triangular pediments.71

Wall Treatments

The manner in which paint and wallpaper are employed could further develop the themes of variation and change already described. Again, we believe that Botetourt intended to finish the pair of rooms with plain paper and gilt borders, but that he only completed the ballroom. Thus he seems to have considered both rooms to be of considerable importance, and to some degree he hoped to treat them en suite. In addition, though, the sequence of his remodeling can be interpreted as another indication of the ballroom's superiority. Not only was the larger room initially finished in a better manner, it was the first (and perhaps the only) room to be remodeled. At the time of Botetourt's death, the smaller room may have had paint and conceivably wall covering that was nearly twenty years old, and the distinction between the two rooms would have been particularly evident. If we are to interpret the Palace to Botetourt's tenure, variation in the two rooms should be no less evident in our recreation.

The present paint and paper scheme in the ballroom seems entirely reasonable. The exact form of the gilt borders can be debated, but the blue paper is extremely well executed and the choice of "dead white" paint for 71 woodwork is probably correct.72 The question of precisely how to treat the supper room surfaces deserves further research, including review of recent paint analysis and additional investigation in selected Virginia houses. Very competent analysis recently has been done in a number of houses in the region, but patterns of stylistic change and social variation have not been systematically addressed.73 Tentative suggestions can be made, however. The trim should probably be painted with a less arresting color available at mid-century, possibly "stone."74 The plaster walls could 72 be whitewashed, finished with a paint containing distemper and color, or covered with a variety of wallpaper fashionable prior to 1770. The last option could be especially interesting, if we chose a flocked or otherwise decorated paper, as plain papers appear to have become fashionable after 1751.75 To reinforce the older, less fashionable appearance of the room, the paper could be allowed to fade and become dingy.

It would seem to be a mistake to install matching blue paper with gilt borders in the supper room, if we wish 73 to interpret the Botetourt era. The only thing we know beyond doubt about the finish of the room in October, 1770 is that the new paper and borders had not been installed. Use of matching material might be a reasonable course if the Palace interpretation focused on Lord Dunmore, who could have installed Botetourt's remaining paper, but it would evince confused philosophy if used in conjunction with predominately Botetourt furnishings.76 To have integrity, restorations and reconstructions must reflect the realities of people's accomplishments, not their intentions. The discovery of our subjects' aspirations is extremely important, but intentions are often unfulfilled. To fulfill them ourselves denies the essential realities of past life that history museums are charged with presenting. Moreover, contrasting the remodeled ballroom with a rather institutional, slightly out-of-date supper room provides an excellent opportunity to interpret the taste and personal style of an individual--in this case a governor with considerable pretensions as a trend-setter in Virginia.

74Final Thoughts

Replacement of virtually all existing interior woodwork in the ballroom wing would be an expensive undertaking, and its benefits should be carefully weighed. What we have attempted to make clear is that this option has a coherence derived from recent scholarship. Because of the direct relationship of the two rooms, it would not seem reasonable to change one room but not the other. The present finish of the supper room is perhaps most conspicuously at odds with the circumstantial evidence cited here, but the ballroom finish is no less ahistorical in its particular context.

The committee should also consider alterations in the context of the entire building. Despite the extensive furnishing and color changes of five years ago, the reconstructed building remains largely a product of 1930-era thinking. This thinking was extensive, thoughtful, and talented, but it nonetheless reflects restoration philosophy in that era, as well as the evidence then available. Our present research has not focused on the main block, but potential problems are evident. To choose a few from a number of possible examples, the stairway includes details drawn from buildings much earlier than the Palace, the chambers have woodwork that is much more costly than one 76 would expect for private second-floor rooms, and the gardens are focused on a parterre that was removed when the ballroom wing was added. Substantial documentation and masonry fragments helped to make the exterior of the main block very believable, but the rear wing suffered from the lack of comparable evidence. Largely working in a vacuum, the architects developed elevations that now seem both too elaborate and too early. The view of the Palace from the gardens is a beloved American icon, but it includes significant features that are unlikely to have existed in Botetourt's time. The tall and thin window proportions, the gauged brick panels below the windows, and the rich north door surround all betray their earlier eighteenth-century sources, and the inclusion of sumptuous gilt and silvered arms in the pediment is scarcely credible.77 At the furthest extremes of skepticism, J. T. Smith has suggested that the walls of the supper room may have been lower than those of the ballroom.

My point is not that all is lost, and that we should live quietly with old mistakes.78 Rather, it is that

Fig. 24. Palace ballroom wing, form the northeast, December 1933. Photo by Richard Nivison.

78

decisions about parts of the Palace should be made within a broad, carefully considered policy that ensures a coherent interpretive product.

Fig. 24. Palace ballroom wing, form the northeast, December 1933. Photo by Richard Nivison.

78

decisions about parts of the Palace should be made within a broad, carefully considered policy that ensures a coherent interpretive product.

One perspective is that the Palace, perhaps like the Raleigh Tavern, is not so much a flawed reconstruction as it is an extremely artful and important expression of early twentieth-century American longing for a reassuring national heritage. This need not be regarded as a reactionary view. The possibility exists that 1931 is as useful an era to study as 1770, and that Colonial Williamsburg has a place in the analysis. Recent historians have increasingly focused on the implications of history-oriented architecture and decorative arts in the early twentieth century.79, From this 79 perspective, substantial alterations to the Palace would damage a major monument of the Colonial Revival, and the new product would still fall short of an entirely accurate representation. Following this logic, the Foundation might accept the Palace with its interesting contradictions as a reasonable environment for teaching and use its resources to develop and refine other equally important presentations of life in the eighteenth-century Williamsburg.

Others argue that the Palace is a crucial component in our portrayal of the range of Virginia culture, and that it should reflect the most current scholarship whenever possible. A major step was taken in the recent refurnishing, and the same philosophy should direct future decisions. Carried to its logical conclusion, this perspective would lead to a gradual revision of interior and exterior features, in hopes that scholarship would not drastically change in the interim. Substantial landscape features as well as the exterior of the 1751 wing and details in a sizable number of rooms ultimately could be affected.

The Historic Area is a large and complex resource which offers ample opportunity for thoughtful interpretation 80 of a great range of themes, including the variety of eighteenth-century life and the attractions of the Colonial Revival. Both can be generously accommodated, but there are certain points at which difficult decisions are inevitable. It remains for the Program Planning Committee to assess how the balance will affect the Palace reconstruction.

Footnotes

1 Marcus Whiffen, The Public Buildings of Williamsburg, Colonial Williamsburg, Williamsburg, 1958, pp. 53-66, 172-181.

The north pavilion encloses a maze of stables and its mate on the south houses what is now identified as the ballroom and billiards room. The two latter rooms seem to have been independently approached through an anteroom, and there is also direct access to the billiards room from the colonnade, conceivably for service. This pavilion is particularly interesting because the scale of the ballroom relative to the main block is much like that at the Palace. Further, the attendant room now identified with billiards has a spatial relationship reminiscent of the supper room. Possible service access to the smaller room makes this relationship all the more intriguing.

Charles H. Wood., ed., Hopetoun House, Pilgrim Press Ltd., Derby, circa 1960; John Fleming, "Hopetoun House, West Lothian," Country Life, January 5 and 12, 1956; William Adam, Vitruvius Scoticus, Paul Harris Publishing, Edinburgh, 1980, p. 28 and pls. 14-19. I am indebted to Calder Loth and Peter Hodson for calling the Hopetoun room to my attention.