The College of William and Mary

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series -210

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY

A BRIEF SKETCH OF THE MAIN BUILDING OF THE COLLEGE, AND OF THE ROOMS TO BE RESTORED TO THEIR EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY APPEARANCE.

With Appended Illustrations of English School-Rooms, Halls, Chapels, Libraries, and other Rooms and Furnishings in English Schools and Colleges.

PREFACE

The College of William and Mary, the design of its original building attributed to Sir Christopher Wren, suffered disastrous fires in 1705, 1859, and 1862. Although only its sturdy brick exterior walls were left standing after each of the fires, these were strong enough to again incorporate the main college building, and were used in the rebuilding in 1710-1716, 1859, and 1868-1869.

The furnishings, library and philosophical apparatus, which were destroyed in the several fires, could be and were replaced. Many of the college records which were destroyed could, of course, never be replaced The early records of the original Trustees and the Visitors and Governors of the College are missing. Copies of minutes of several meetings of the Visitors and Governors in 1716 have survived in the family papers of the Rector of that body; and the detail given in these indicates the extent of the loss the College has suffered in the destruction of these early records. The registers of students prior to ca. 1862 are also missing. Scattered Bursar's records for the 1754-1766 and 1770-1777 period list names of some of the students then attending the College, in connection with their payments for board and College fees; and a volume of Faculty Minutes for 1729-1784, with some pages missing, lists names of a few of the students who were called to the attention of the Faculty during that period for one reason or another. The archivists of the College, during recent years, have attempted to collect manuscripts from all available sources in this country and in England, and also material from printed and published sources, in an effort to fill in some of the gaps, but its still felt more must be done before there is sufficient data for a definitive history of the College.

We have gone through what is available in the College archives, and in published sources, as well as in microfilmed material from the British records, and offer in this report a brief account of the College, with what detail is now available on its main building and furnishings. To this we have appended brief notes on several English grammar schools and colleges, which may have influenced the academic structure of the College of William and Mary; and also illustrations of school-rooms, halls, chapels and other rooms in English schools and colleges, which may have influenced its design architecturally .

Mary R. M. Goodwin

Research Department June, 1967

C0NTENTS

| Preface | i |

| Brief account of the College, 1691-1869/70 | 1 - 32 |

| The Grammar School and its Room | 33 - 48 |

| The Moral Philosophy School and its Room | 49 - 55 |

| The "Great Hall" and its Uses | 56 - 60 |

| The School of Natural Philosophy | 61 - 68 |

| The Chapel | 69 - 85 |

| The Convocation Room or "Blue Room" | 86 - 91 |

| The Northwest Corner Room, 2nd floor ("Common Room") | 92 - 94 |

| Dormitories | 95 - 96 (272 - 273 |

| The Library | 24 - 25 (280 - 283 |

| The Kitchen | 303 - 304 |

| School Rooms and Furniture | 95 - 154 |

| Halls or Refectories and Furniture | 155 - 198 |

| Chapels and Furniture | 199 - 255 |

| Convocation Rooms and Furniture | 256 - 260 |

| Common Rooms and Furniture | 261 - 271 |

| Dormitories and Furniture | 272 - 279 |

| Libraries and Furniture | 280 - 302 |

| Kitchens and Furniture | 303 - 313 |

| Quadrangles | 314 - 318 |

| iii | |

| NOTES - WILLIAM AND MARY COLLEGE (pages 1-94) | 319 - 378 |

| INDEX | 379 - &c |

| THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM & MARY The College of William & Mary (restored) 1928-1931 | Frontispiece |

| The Rev. James Blair (portrait circa 1735) | 10 |

| Michel's sketch of the College of William & Mary, 1702 | 13 |

| The College of William & Mary circa 1732-1747, (copperplate engraving from Bodleian Library) | 16 |

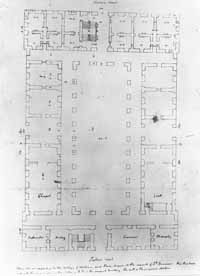

| Floor-plan of the College of William & Mary showing proposed addition (Thomas Jefferson, circa 1772) | 19 |

| Partial List of "Physical Apparatus" purchased in 1767 | 21 |

| Lithograph of the College of William & Mary, from Millington painting of circa 1840 | 23 |

| Lithograph of the College of William & Mary, as rebuilt in 1859 | 27 |

| Photograph (circa 1870) of the College of William and Mary as rebuilt after the fire of 1862 | 29 |

| Girl's Drawing (1856) of the East Front of the College of William & Mary | 47 |

| Girl's Drawing (1856) of the Rear (West side) of the College of William & Mary | 48 |

| Charter-House, London (brief note on School and illustration) | 97 - 98 |

| Christ's Hospital, London (note on School and illustrations) | 99 - 102 |

| Eton College (note on Eton and illustrations) | 103 - 114 |

| The Free School of Harrow (note on School and illustration) | 115 - 117 |

| v | |

| Merchant Taylors' School, London (note on School and illustrations) | 118 - 121 |

| St. Paul's School, London (note on School and illustration) | 122 - 124 |

| Westminster School, London (note on School and illustrations ) | 125 - 131 |

| Winchester College (notes on College and illustrations ) | 132 - 143 |

| Choir-Room, Salisbury, Wilts | 144 - 147 |

| Scholars' Ink Bottle and Pages from Text Books | 148 - 154 |

| All Souls College, Oxford (note on College and illustrations) | 155 - 158 |

| Charter-House, London (note and illustration) | 159 - 160 |

| Chelsea Hospital , London (note and illustration) | 161 - 163 |

| Christ's Hospital, London (note and illustration) | 164 - 165 |

| Clare Hall, Cambridge (note and illustrations ) | 166 - 172 |

| Emmanuel College, Cambridge (note and illustrations). | 173 - 178 |

| Eton College (brief note and illustrations) | 179 - 181 |

| Trinity Hall, Cambridge (brief note and illustrations) | 182 - 185 |

| University College, Oxford (note and illustration) | 186 - 188 |

| Westminster School, London (brief note and illustration). | 189 - 190 |

| Charcoal Brazier used in Hall of Trinity College, Cambridge | 191 |

| Plates, Spoons, "Sconce Tankard," Jugs, etc. used in Halls | 192 - 198 |

| All Souls College, Oxford University | 199 - 200 |

| Clare Hall, Cambridge University | 201 - 205 |

| Emmanuel College, Cambridge University | 206 - 214 |

| Eton College | 215 - 218 |

| Jesus College, Oxford University. | 219 - 221 |

| Magdalen College, Oxford University. | 222 - 224 |

| New College, Oxford University | 225 - 227 |

| Pembroke College, Cambridge University | 228 - 235 |

| Queen's College, Oxford University | 236 - 238 |

| Trinity College , Cambridge University | 239 - 245 |

| Trinity Hall, Cambridge University | 246 - 251 |

| Winchester College | 252 - 255 |

| At University of Glasgow and Emmanuel College | 256 - 260 |

| All Souls College, Oxford University | 261 - 262 |

| Charter-House, London | 263 |

| Clare Hall, Cambridge University. | 264 - 265 |

| Queen 's College, Oxford University | 266 |

| Trinity College, Cambridge University | 267 - 268 |

| Worcester College, Oxford University | 269 |

| Silver used by Professors, Trinity Hall, Cambridge | 270 - 271 |

| Eton College Dormitory | 274 |

| Westminster School Dormitory | 275 |

| Winchester College Dormitory Furniture — "Scobs" | 276 |

| Students Rooms, University of St. Andrews. | 277 - 279 |

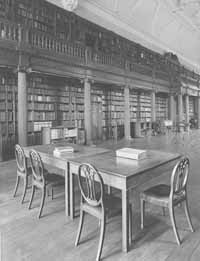

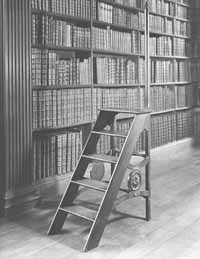

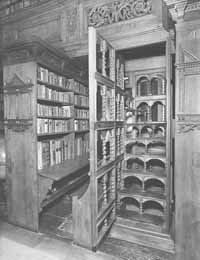

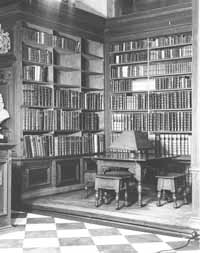

| All Souls College Library, Oxford University | 284 - 286 |

| Christ Church Library, Oxford University | 287 - 294 |

| Jesus College Library, Oxford University | 295 |

| Queen's College Library, Oxford University | 296 - 298 |

| Trinity College Library, Cambridge University. | 299 - 302 |

| Inventories of Kitchen and Larders at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and at Winchester College | 305 - 309 |

| Christ Church Kitchen | 310 |

| Eton Kitchen Furnishings. | 311 - 313 |

| Christ Church Quadrangle | 314 - 315 |

| Eton Quadrangle and new School Building | 316 - 317 |

| Wadham College Quadrangle, Oxford University | 318 |

THE MAIN BUILDING OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY

THE MAIN BUILDING OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY

After its restoration in 1928-1931 to its circa 1716-1859 appearance. The statue in the right foreground is of Norborne Berkeley, Baron de Botetourt, who was Governor of Virginia from 1768 until his death in October, 1770. The statue was ordered by the General Assembly of Virginia, and stood in the Capitol building in Williamsburg from ca. 1773 until ca. 1801, when it was moved to the College yard. It has been recently removed from the yard to the new Earl Gregg Swem Library for safe-keeping.

THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY IN VIRGINIA

Until the last decade of Virginia's first century, no attempts to establish a college in that Colony had met with success. A college at Henrico in Virginia (principally for the education and conversion of the Indians) was proposed circa 1618 by the Virginia Company of London — the Company under whose auspices the first permanent English settlement in the new world had been made at what became James City [Jamestown] in Virginia in 1607. A start on the college at Henrico was wiped out by the Indian massacre of 1622.1 A feeble effort to collect funds for a college "for the advancement of learning& & provision of an able and successive ministry" in Virginia was made in 1661, but it came to nothing.2

A number of prosperous planters and merchants in the Colony sent their sons home to England to school and college. Other families employed tutors to teach their children at home. Two or three free schools had been privately endowed in Virginia well before the end of the century, but these could take care of comparatively few children. Many of the poorer inhabitants, as in England, bound their sons out for a period of years to a "master" to learn a trade, art, or profession.3

THE FOUNDATION OF THE COLLEGE

The establishment of a college — the College of William and Mary — in Virginia was largely due to the efforts of two men, the Rev. Mr. James Blair,4 Commissary (or deputy) in Virginia of the Bishop of London, and the Lieutenant Governor, Francis Nicholson.5 The provision of ministers in the Colony was a strong talking point in efforts to procure a charter; and to this a plan for education and conversion of the Indians (a favorite with the powers in England — mentioned in the original charter for Virginia in 1606) was soon added. The Rev. Mr. James Blair came to Virginia in 1685 as minister of Varina Parish in Henrico County, and was appointed Commissary of the Bishop of London in 1689. In 1690 Blair and others of 2 the "Clergy of Virginia" prepared "Propositions" or proposals for a college in Virginia to consist of "three Schools, Vizt Grammar, Phylosophy, & Divinity," which proposals Blair presented to the Governor, Council, and House of Burgesses in the spring of 1691. Francis Nicholson, the Lieutenant-Governor, promoted the proposals in the Council and in the House, and got immediate results. A "Supplication"6 was prepared by the Assembly to King William and Queen Mary requesting a royal charter and endowment for a College, to be named in their honor; committees were appointed to solicit funds in Virginia and in England for the College; and the Rev. Mr. Blair was sent to England in 1691 with detailed instructions from the Governor and General Assembly as to how to proceed in obtaining the charter, and endowments, gifts and legacies. He was also supplied with eighteen names of those the Assembly had elected to become Trustees for the College.

The "Severall Propositions" of the Clergy suggested sources of funds for the proposed college; and urged the provision of "able & fitting" masters and professors for the three schools. For the Grammar School, "a Master, & an able Usher," were suggested — the Master to be paid £80 a year "with the liberty to take fifteen shillings Annum of each schollar, excepting 20 poor schollars, who are to be taught Gratis," and the Usher £50 a year, "& liberty to take five shillings yearly of each schollar, except the twenty poor schollars aforesd." The two professors of the Philosophy School (one "for Logick & natural Phylosophy, & the other for ye Mathematicks") were to be paid £80 each per annum, and to receive £1 a year of each scholar "excepting tenn poor Schollars" who were "to be taught gratis"; and the two professors of the Divinity School ("one able Professor, skill'd in ye Orientall Languages, & one able & grave divine, to be President of the Colledge") were to receive £150 each per annum, with no fees from students in their School. It was also suggested that the proposed college be erected "as near as may be to Centre of Country."7

The instructions given the Rev. Mr. James Blair were approved by the House of Burgesses on May 21, 1691 and were signed by Francis Nicholson. Mr. Blair was ordered to "goe directly from hence, wth this present Fleet." He was to "peruse best Charters in England, whereby Free Schooles 3 & Colledges have been founded," and use every effort to procure from their Majesties "an ample Charter for a Free Schoole & Colledge, wherein shall be taught the Lattin, Greek, & Hebrew Tongues, together wth Philosophy Mathematicks & Divinity." He was to have the college founded in the names of eighteen Trustees, the Lieutenant-Governor, Francis Nicholson, being the first named. The Trustees were to become Governors and Visitors of the College when it was founded. Blair was also to "procure a good Schoolemaster, Usher & Writeing Master" — the latter to teach "Writeing & Arithmetick" — and to obtain "Subscriptions, Guifts and Benevolences" in England for the College. To accomplish all this he was to ask the assistance of the Bishops of London, Salisbury, and St. Asaph , the governor general of Virginia — Lord Howard of Effingham, and others.8

Before November 12, 1691, Blair had received aid from a number of people, among them the Bishop of London (Henry Compton), the Bishop of Worcester (Edward Stillingfleet), the Archbishop of Canterbury (John Tillotson). The Bishop of Worcester had talked with Queen Mary about the plan for the College, who "seemed to like it extraordinarily"; and on November 12, 1691, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Howard of Effingham introduced James Blair to King William, who had been away from London when Blair arrived. By that time Blair had been persuaded that "at first a Grammar school being the only thing" that could be managed, and a "good Schoolmaster & Usher" being "enough to manage that," the "first man of all the masters" to be appointed should be the President, to manage the Schoolmaster and School.9 Blair was named President and first Professor of Divinity in the charter.

After more than a year in England, the Rev. Mr. Blair succeeded in obtaining the charter and endowments, in accordance with his instructions ; also a seal for the College, a number of gifts and contributions towards it, and a master, usher, and writing master for the Grammar School. He returned to Virginia; and on September 1, 1693, he attended a meeting of the Governor (Sir Edmund Andros) and Council at James City to present the charter, which was that day read in Council and ordered to be recorded. 10

The Charter granted by King William and Queen Mary was signed under the Privy Seal on February 8, 1692/3, and 4 before leaving England Blair had presented a copy of it to the Commissioners of Customs in London. He had also paid eight shillings for "a box for the Charter and a Tinn box for the Seal," and paid lawyers in London "for advice in drawing the Charter and their Clerks at times" £29:15:6. Mr. Nichols, "who wrote the Charter there," received 2 Guineas, or £2:3:8.11 The charter read in part:

"… Forasmuch as our well-beloved and trusty Subjects, of our Colony of Virginia, have had it in their Minds, and have proposed to themselves, to the end that the Church of Virginia may be furnish'd with a Seminary of Ministers of the Gospel, and that the Youth may be piously educated in good Letters and Manners, and the Christian Faith may be propagated amongst the western Indians, to the Glory of Almighty God, to make, found, and establish a certain Place of universal Study, or perpetual College of Divinity, Philosophy, Languages and other good Arts and Sciences, consisting of one President, six Masters or Professors, and an hundred Scholars, more or less, according to the Ability of the said College, and the Statutes of the same, to be made, encreased, diminished, or changed upon the Place, by certain Trustees nominated and elected by the General Assembly aforesaid; to wit, … [eighteen trustees named, headed by "Francis Nicholson, our Lieutenant Governor in our Colonies of Virginia and Maryland," and including members of the Council, the House of Burgesses, and the Clergy in Virginia.] … We, taking the Premises seriously into our Consideration, and earnestly desiring that, as far as in us lies, true Philosophy, and other good and liberal Arts and Sciences may be promoted, and that the orthodox Christian Faith may be propagated … have granted and given Leave … to the said Francis Nicholson, … [the 18 Trustees named] … to erect, found and establish a certain Place of universal Study, or perpetual College, for Divinity, Philosophy, Languages, and other good Arts and Sciences, …"125 The Trustees were empowered by the charter to hold in their names, all lands, endowments, gifts, and subscriptions, to be granted or given for erecting and furnishing the College, and to nominate persons for masters and professors when needed, until the College was built and furnished and had its full faculty — a President and six Masters or Professors. At that time the Trustees were to transfer the College, to be "called and denominated for ever, The College of William and Mary in Virginia," to the President and Professors; the "President and Masters, or Professors" were then to be "a Body Politick and incorporate, in Deed and Name," with a common seal and with "perpetual Succession." As has been noted, the Rev. Mr. James Blair was named in the charter the first President "during his natural Life." After the College was founded and erected, the Trustees were to become the true and sole "Visitors and Governors of the said College for ever," with power to make so many "Rules, Laws, Statutes, Orders and Injunctions, for the good and wholesome Government of the said College, as to them … and their Successors" should "seem most fit and expedient." James Blair was a Trustee and a Visitor and Governor of the College, and was also named first Rector of the Visitors and Governors, "for one Year next ensuing the Foundation" of the College; and Henry Compton, Bishop of London, was named the first Chancellor of the College, to continue in office for seven years. The Rector, Visitors, and Governors had the power to elect "some other eminent and discreet Person from Time to Time to be Chancellor" for "the space of seven Years then next ensuing"; they also appointed the new masters and professors.

For the charge and expense of "erecting, building, founding and furnishing" the College, and supporting its President and Masters, the charter granted the sum of £1985:14:10 "lawful Money of England," that had been raised out of the quitrents in that Colony; and the auditor, William Byrd, was ordered to pay that sum to the Trustees. The charter also granted the one-penny-a-pound tax, which had been levied by Parliament since 1673 on all tobacco exported to Great Britain from Virginia and Maryland, to be applied to the building, furnishing, and other uses of the College; and it granted the College some 20,000 acres (two tracts of unoccupied land in Virginia known as Blackwater Swamp and Pamunkey Neck) to be used to produce income — charging the College as quitrent for the land, "two Copies of Latin 6 Verses yearly, on every Fifth Day of November." These verses were to be presented to the Governor or Lieutenant Governor at his house.

The College, when it had been completely founded and erected, was to be allowed a voice in the colonial government. The charter gave the President and Masters or Professors power to elect from their own number, or from the Visitors and Governors, or from "the better sort of Inhabitants" of the Colony, a representative for the College to sit in the House of Burgesses.13

In October, 1693, after considering several possible sites for William and Mary (among them land in Gloucester, at Yorktown, and on the Pamunkey Neck tract granted to the College), Middle Plantation, which was inland between the York and James rivers, was selected by the General Assembly to be the site of the College.14 The Act of Assembly "ascertaining the place for erecting the College of William and Mary" ordered that the College be built "as neare the church [Bruton Parish Church] now standing in Middle Plantation old ffields as convenience will permitt." 15 The Trustees paid Capt. Thomas Ballard £170 for "330 acres of land whereon ye Colledge" was to be built — a tract of land which Thomas Ludwell, Secretary of the Colony, had sold Thomas Ballard in 1674/5 for £110 sterling. 16

To further support and maintain the College of William and Mary, the General Assembly of Virginia, in November, 1693, passed an act laying an imposition upon skins and furs carried out of the Colony by land or water, to go into effect the following January.17

A surveyor for the building, Mr. Thomas Hadley, and some workmen, including bricklayers, were brought over from England, as were many of the building materials including paving stones. Bricks, shell for lime, timber and shingles were supplied in the Colony — in 1695 Col. Daniel Parke of "Queen's Creek" plantation, a few miles from the site of the College, was paid £547:07:00 for bricks, at 14 shillings per thousand.18 Thursday, the 8th of August, 1695 , was appointed "for the laying the Foundation" of the building. The Governor, Sir Edmund Andros, members of the Council, and officials and Trustees of the College 7 attended the ceremony, which was carried out, according to one of those present, "with the best Solemnity wee were capeable" of.19

The erection of the College building, which was intended to be a quadrangle, went slowly. Quarrels between the Governor, the President of the College, some of the Trustees and members of the Council, contributed to this; and by the spring of 1697, funds were exhausted. In April, 1697, the Trustees wrote the Governor, Sir Edmund Andros:

" wee have carried on the building of two sides of the designed square of the College (wch was all wee judged wee had money to goe through with) and have brought up the Walls of ye Said building to the roof wch hope in a short time will be finished, Collo Ludwell haveing promised to Shingle it upon Creditt."20The Trustees also sent Governor Andros accounts of expenditures to April 15, 1697, showing that £3889:01:01 had been spent on the building, salaries, supplies, etc., which was £170:08:02 more than had been received at that time.21 President Blair laid blame for most of the difficulties on Governor Andros; and in spring or summer of 1697 Blair went to England to attempt to collect additional funds for the College, and to have the Governor deposed. Blair and William Byrd attended a conference at Lambeth Palace, where they were examined by the Archbishop of Canterbury concerning the charges and counter-charges involved in the Blair-Andros controversy.22 Blair returned to Virginia with funds from the estate of the Hon. Robert Boyle (the well-known English natural philosopher who died in 1691) arising from investments in the Manor of Brafferton in Yorkshire, for keeping at the College so many Indian children as could be maintained by the funds. They were to be kept "in Sicknesse and health in Meat drink Washing, Lodgeing Cloathes Medicines books and Educacon from the first beginning of Letters till they are ready to receive Orders and be thought Sufficient to be sent abroad to preach and Convert the Indians," allowing £14 "per Annum for every such Child."23 Governor Andros was soon recalled, and Francis Nicholson was returned to Virginia as full Governor in 1698.24

Prior to the completion of the College building, a Grammar School was started. This was held up for a time 8 after President Blair's return with the charter, until a suitable place could be found at Middle Plantation for his residence, and for the school. The school was probably established soon after Col. William Brown was paid £45 "for repairing ye School house" in 1694.25 In April, 1697, the Trustees for the College reported that they had "founded a grammer School wch is well furnisht wth a good Schoolmaster Usher and Writing-master in wch the schollrs make great proficiency in their studies to ye Genll satisfacon of their parents and guardians."26

The College building was almost ready for use in May, 1699, when a May Day celebration was held there.27 Five of the scholars made speeches before a large gathering at the College, including Governor Francis Nicholson, and members of the Council and House of Burgesses. The third scholar's speech (undoubtedly sponsored by the Governor) concerned the moving of the seat of government from James City to Middle Plantation, where Bruton Parish Church and the College then stood. This third speech was read and considered in the House of Burgesses on May 18th, and not long thereafter Governor Nicholson's plan for building a Capitol and the City of Williamsburg at Middle Plantation was approved by the General Assembly.28

On May 27, 1700, Governor Nicholson wrote the Archbishop of Canterbury:

" We have agreed that (God willing) after next Xmas the President [Blair] shall go & live in the College, the Latin Master, Usher & Writing Master, & so many Scholars as are willing, to board there; & Mr President Blair hath undertaken for the first year to provide for their accommodation; & by this opportunity of the fleet, necessaries for the Kitchen Pantry, &c., are to be sent for."29

President Blair and his wife, the Grammar Master, Usher, scholars, and College servants probably moved into the building late in 1700; the President's quarters were on the south side of the front or east wing of the first floor of the building, across the entrance hall from the Grammar School Room.30 There were 29 Scholars in the Grammar School in 1702.31

9In December, 1700, and until the new Capitol (ordered built in 1699, when it was decided to move the seat of government and build the City of Williamsburg at Middle Plantation) was ready for use — circa 1704 — meetings of the General Assembly were held in the College building.32 The House of Burgesses met in the Great Hall, the Council probably met in the large room on the second floor above the Grammar-School Room (the site of the room later used for meetings of the President and Masters, etc.), and convenient space was found for the Clerk of the House of Burgesses, Clerk of the Council, and for the office and records of the Secretary of the Colony.33 On several occasions, when it was necessary to be in town during the 1700-1705 period, some of the Council, or Governors of the College, lodged in the building.34

According to Robert Beverley, in his History & Present State of Virginia, published in London, in 1705, the College building was —

"… to consist of a Quadrangle, two sides of which, are yet only carryed up. In this part are already finished all conveniences of Cooking, Brewing, Baking, &c. and convenient Rooms for the Reception of the President, and Masters, with many more Scholars than are as yet come to it; in this part are also the Hall, and School-Room."35

Quarrels between President Blair, Governor Nicholson, and other Trustees of the College, became more vehement, and Blair and others finally succeeded in having Governor Nicholson removed from office.36 Mungo Ingles, who had come over from England to be the first Master of the Grammar School, sided with the Governor, and resigned as Grammar-master in September 1705.37 On October 29, 1705, the College building caught fire, apparently from a dirty chimney which set the roof afire, and the building was gutted.38

It was not until 1709 that the Visitors and Governors of the College were able to consider plans for the re-building of the edifice, Queen Anne having granted £500 out of the quitrents revenue towards the rebuilding in March, 1708/9. The Visitors and Governors decided to rebuild on the old walls; and in October, 1709, an agreement was made with

10

THE REV. JAMES BLAIR, PRESIDENT OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY, 1693-1746.

THE REV. JAMES BLAIR, PRESIDENT OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY, 1693-1746.

Portrait by Charles Bridges, circa 1735, showing the College building in the background. Portrait at College of William and Mary.

11

John Tullitt to undertake the building for £2,000, "provided he might wood off the College land and all assistants from England to come at the College's risk." Alexander Spotswood, who arrived in Virginia as Lieutenant-Governor in June, 1710, took an active interest in both the rebuilding of the College, and its design. However, although Queen Anne granted a second £500 out of the quitrents in April, 1710, the quitrents were almost exhausted at that time, and funds for building were slow in accumulating. The Grammar School was continued in a School-house near the College; and by 1712 there were also about twenty Indian children being taught by an Indian Master on the revenue granted the College from Mr. Boyle's Brafferton estate. By 1716 the building was almost completed to its original size (which was half of the intended quadrangle), and furnishings for the building were sent for to England.39

In February , 1729, having at last reached its full development as required in the charter, with its faculty of a President and six Masters or Professors, the surviving Trustees of the College transferred the College of William and Mary to the President and Masters and Professors.40 By this time a separate brick building (built circa 1723 and known as "The Brafferton") had been erected near the College for the Indian School founded by Mr. Boyle's charity.41 In 1729-1732 the third side of the proposed quadrangle, the Chapel wing, was built.42 A brick house, opposite to "The Brafferton," was erected for the President in 1731-1733, and President Blair was able to move out of the College building.43 The College remained in about this state, with necessary repairs from time to time, up to the outbreak of the American Revolution; although in 1772 it was decided to enlarge the building and complete the quadrangle. A plan for the addition was drawn by Thomas Jefferson. However, this work had barely gotten under way when events immediately prior to the Revolution caused it to be discontinued.44

In 1779-1780 the College was reorganized and made a University, with schools of Natural Philosophy and Mathematics, Law, Anatomy and Medicine, Moral Philosophy, the Laws of Nature & of Nations, & of Fine Arts, and Modern Languages. The Grammar School and the Divinity School were discontinued, as were meals or "commons" in the Hall.45

12However in 1781, with the invasion of the British forces, the university became "a Desert," the student "converted into the Warrior," and the buildings put to military uses.46 The main building served as a hospital for the French soldiers from the fall of 1781 until the summer of 1782.47 The President's House was occupied by the British General, Lord Cornwallis, for a time in June, 1781; and used as a hospital for French officers, from October until December, 1781, when it was accidentally burned. It was repaired by funds from the French Government.48

In October , 1782, about a year after the British surrender at Yorktown, the University of William and Mary reopened.49 Loss of approximately three-fourths of its revenues at the time of the Revolution was a serious handicap; but in 1795 there were about fifty or sixty scholars in the Grammar School, which had been re-established, and about thirty or forty in the Philosophy and Law Schools.50

THE FIRST COLLEGE BUILDING: 1695-1705

This building, which was designed by, or under the supervision of, Sir Christopher Wren,51 was intended to be a quadrangle; but there was only money enough to build two sides of the proposed square — the front, or east side, and the Hall, or west side. The east front, with the main entrance in its center, was approximately 46 feet wide by 138 feet long, with a "piazza" on its west side. From a very distorted drawing of the building made by Franz Ludwig Michel, of Berne, Switzerland — who visited the College in June 1702, and described a celebration held there to announce the death of King William III and the accession of Queen Anne — this front of the building appeared to have had a high basement, three full stories, and a half-story with dormer windows in the roof — also a balcony at the center of the second story, over the entrance, and a cupola.52 The Hall (or "Great Hall" as it was sometimes called) which projected towards the west from the rear of the east front, measured about 32 feet wide by 64 feet long, and had only one story above it.53 There was a gallery in the hall, which could be reached by "a pair of back stairs," by which students rooming in the "northermost Chamber in ye very roof," might descend into the Hall. It is thought that the central stairs in this building, which were "in the Middle of the Pile,"

13

THE EAST FRONT OF THE "WREN BUILDING" OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM & MARY - 1702

THE EAST FRONT OF THE "WREN BUILDING" OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM & MARY - 1702

(From a drawing by Franz Ludwig Michel in 1702.)

14

went straight up from the front entrance hall.54

From accounts of the building which have survived, the President and his wife, the Grammar Master, Usher, Grammar students (possibly about 25 to 30), and College servants, moved into this building late in 1700.55 The President's apartment was on the first floor, on the south side of the main entrance beyond the stair hall. The fire which destroyed the building in October, 1705, started in the roof — some said from a fire in a dirty chimney in the President's quarters.56 The Grammar School Room was to the north of the main entrance, and is thought to have been the same size as the room in the present building, 24-feet wide by 32-feet 3-inches long. It had double doors from the entrance hall at its south end, and apparently had a door "next to the North end." A General Map of the World hung at its south end.57 The School was doubtless furnished with a desk for the Master, a desk for the Usher, and benches or forms for the scholars, similar to the furnishings in such schools in England — especially those designed or influenced by Christopher Wren.58 This furniture may have been made in Virginia, from Wren's design, or it may have been sent over from England. Most of the other furnishings for the building were supplied by the London merchants, Messrs. Micajah and Richard Perry.59 The Hall would have been furnished with tables and benches, similar to those used in English halls of the period.60 It served as a dining hall or refectory for the President, Masters and Ushers, Scholars, and College officials; and, as the proposed Chapel wing had not been built, it also served other uses. As the President, the Rev. James Blair, told a visitor: "Here we sometimes preach and pray, and sometimes we fiddle and dance; the one to edify, and the other to divert us."61 The Hall was at times the meeting place of the House of Burgesses of Virginia in 1700-1704, after the seat of government was moved from James City and before the new Capitol building in the new City of Williamsburg had been completed.62

Rooms or apartments for the Master and Usher were probably on the second or third floor;63 the "Convocation Room," (or room for meetings of the Trustees, Visitors and Governors, and Faculty), and the Library were probably on the second floor. Scholars roomed on the third floor, and in rooms under the roof.64 The facilities for "Cooking, 15 Brewing, Baking, &c." were in the basement under the Hall, President Blair sending to England for "necessaries for the Kitchen Pantry &c." in the spring of 1700.65 College servants, and servants belonging to the President, Master, and Usher, lodged in the basement under the east or front wing of the 1695-1705 building.66

An undated memorandum, evidently made before the fire of 1705, concerning "Several faults in the Building" has survived: The "chimneys in the 2d Story" were "scarce big enough for a Grate, whereas the only firing in this Country being wood, a fire cant be made running the hazard of its falling on the floor"; the "chimney over the Hall hath one of the principal Girders through the middle of the hearth whereby no use can be made of it"; the "ovens" were made within "the Kitchin" but "when they were heated the Smoke was so offensive that it was found necessary to pull them down & build others out of doors."67

As has been noted, the College building was destroyed by fire on the night of October 29, 1705, "the building, Library, and furniture" being "in a small time totally consumed."68

SECOND COLLEGE BUILDING: ca. 1711-1716 - 1859.

In August, 1709, the Visitors and Governors decided to rebuild the College on its old walls, and workmen were appointed to view them and compute the charges. In October, 1709 the Visitors accepted proposals from Mr. John Tullitt to do the work for £2,000 "provided he might wood off the College land and all assistants from England to come at the College's risk."69 The work progressed slowly, and we are told that the Lieutenant-Governor, Alexander Spotswood, who arrived in Virginia in June, 1710, and was an amateur architect or draftsman, had much to do with the design of this second building.70 As before, except for bricks, timber, shingles, lime, and possibly wood for wainscoting available in Virginia, the building materials came from England, as did some of the workmen. This building was probably ready for use between 1716-1718; again it was only one half of the proposed quadrangle.71

16 THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY CA. 1732-1747.

THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY CA. 1732-1747.

(1) The "Brafferton" (or Indian School) built ca. 1723. (2) The east front of the "Wren Building," rebuilt on original walls after fire of 1705, and completed ca. 1716. {3) The President's House, 1731-1733 (5) The rear of the "Wren Building " showing the Hall, and the Chapel wing — Chapel wing built 1729-1732. [From a Copperplate showing the College, the Capitol, and the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg, found in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, not dated, but apparently made between 1733 when the President's House was completed and 1747 when the Capitol building (not here shown) burned.]

The building erected on the old walls, consisting of the east front and the Great Hall, had a full basement; the Hall wing had one floor above it, although it was as high as the east front; and the east front was two and a half stories high, with dormer windows in the roof.

Several contemporary descriptions of the building may be of interest here. The Rev. Hugh Jones, who arrived to teach at the College just before the rebuilding was completed, wrote of it:

"The Front which looks due East is double, and is 136 Foot long. It is a lofty Pile of Brick Building adorn'd with a Cupola. At the North End runs back a large Wing, which is a handsome Hall, answerable to which the Chapel is to be built; and there is a spacious Piazza on the West Side, from one Wing to the other. It is approached by a good Walk, and a grand Entrance by Steps, with good Courts and Gardens about it, with a good House and Apartments for the Indian Master and his Scholars, and Out-Houses; and a large Pasture enclosed like a Park with about 150 Acres of Land adjoining, for occasional Uses.

The Building is beautiful and commodious, being first modelled by Sir Christopher Wren, adapted to the Nature of the Country by the Gentlemen there; and since it was burnt down, it has been rebuilt, and nicely contrived, altered and adorned by the ingenious Direction of Governor Spotswood; and is not altogether unlike Chelsea Hospital."72

In the transfer of the property from the surviving Trustees to the President, Masters and Professors, in 1729, the building erected after the fire of 1705 was described as:

"…more convenient than before, and is now fitted with a hall, and convenient apartments for the schools, and for the lodging of the President, masters, and scholars, and hath in it a convenient chamber set apart for a 18 Library, besides all other offices necessary for the said College, and is adorned with a handsome garden…" 73

In a letter of 1732 to the Bishop of London, after "the Brafferton" had been erected, the Chapel wing had been completed, and the President's House was in the process of construction, the Rev. William Dawson, Professor of Philosophy, "late of Queen's College," Oxford, wrote:

"July 31. The foundations of a common brick House for the President was laid opposite to Brafferton. It is to be finished for £650 current money by Oct. 1733, according to the articles of agreement. These two buildings will appear at a small distance from the East front of the College, before which is a Garden planted with evergreens kept in very good order. The Hall and Chapel, joining to the west Front towards the Kitchen Garden, form two handsome wings. …"74

It is probable that the early interior arrangement of this building was much like that in the first building; with President Blair's room or rooms (his wife had died in 1713) to the south side of the main entrance, on the first floor. It is thought that in this building the main stairway was to the south of the front entrance, and did not go straight up from the entrance hall as in the first building.75 In 1716, apparently before the building was completed, and before President Blair moved into it, the Visitors allowed William Levingston to "make use of the lower Room at the South end of the Colledge" as a dancing school, until "his own dancing school in Williamsburg be finished."76

We know that the Grammar School Room was in the same location in this building as in the first building: a room approximately 24-feet wide by 32-feet long, with double doors from the entrance hall at its south end, and a fireplace at its north end. It had four high windows on its east side, and two on its west side looking onto the piazza.77 It was probably furnished much as was the Grammar School room in the building of 1695-1705; as the style of such school rooms did not change rapidly. Its furnishings

19

THOMAS JEFFERSON'S PLAN, CIRCA 1772, FOR A PROPOSED ADDITION TO THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY, SHOWING USED OF THE EXISTING ROOMS ON THE FIRST FLOOR AT THAT TIME.

THOMAS JEFFERSON'S PLAN, CIRCA 1772, FOR A PROPOSED ADDITION TO THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY, SHOWING USED OF THE EXISTING ROOMS ON THE FIRST FLOOR AT THAT TIME.

(From original in the Henry E. Huntinqton Library, California.)

20

(Master's desk, desk or desks for Ushers, and benches or forms for from about 30 to 40 scholars) may have come from England ready-made, but were more probably made on the place, according to English design, of some hard wood such as oak or walnut, then readily available in Virginia.78

The lecture rooms for the two Professors in the Philosophy School were at the opposite ends of the east front of the College building by the middle of the eighteenth century, if not earlier. The Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy (or "Physicks, Metaphysicks, and Mathematicks,") was at the south end of the building, and the Professor of Moral Philosophy, who taught "Rhetorick, Logick and Ethicks," was at the north end of the building, adjoining the Grammar School room.79

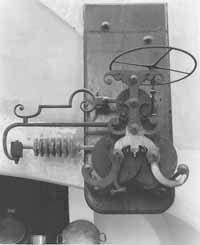

The room marked "Mathematics" on Jefferson's floor plan of the building (see page 19), was probably large enough for the very limited amount of philosophical apparatus owned by the College prior to 1767-1768. When Dr. William Small was Professor of Natural Philosophy at the College (1758-1764), he had little apparatus with which to illustrate his lectures. In 1762 the General Assembly of Virginia appropriated £450 Sterling out of the public funds towards purchasing "a proper Apparatus for the Instruction of the Students … in Natural and Experimental Philosophy";80 and part of this was spent on the "Physical Apparatus" purchased in London by Dr. Small in 1767, at the request of the College. Small spent £332:4:0 on the apparatus, some of which he purchased from Edward Nairne, the famous London maker of physical apparatus, and he was paid £50 by the College for his trouble.81 After the arrival of the apparatus, a separate room in the College was provided for it; but we have not been able to determine from the surviving records what room was used. When the Revolutionary War moved into the Williamsburg-Yorktown area, there was much concern among the College authorities about both the Library and the Apparatus. John Blair, former Bursar of the College, wrote General Washington on October 15, 1781, that the College building was then being used as a hospital for the French Line, who were "now in possess ion of the whole, except the Library, the Apparatus-Room," and one other room in which a professor had remained. George Wythe wrote Washington on October 25, 1781, explaining that there 21

| "Brought forwards | |

| The Fountain Experiment in Vacuo &c. in open air with a Bason &c | 3- 3-0 |

| A Lung's Glass | -10-6 |

| The Barometer Expert | -15-0 |

| Wire Cage for breaking Glasses with 6 brass caps with Valves | 1-11-6 |

| Plates for Attraction & Cohesion | 0-15-0 |

| A Pendulum to Swing in Vacuo | 2- 2-0 |

| A Set of Glasses for the Air Pump | 3-13-6 |

| 6 Pound of Quicksilver | 1- 4-0 |

| A Dipping Needle Compass 9 Inches Dam. with Needles for the Dip | 15-15-0 |

| A Honzonl needle With a center Pin Works for it to stand on for the variation | 0-18-0 |

| £208-17-6 | |

| "Brought over | £208-17-6 |

| a monichord | 4- 4-0 |

| A machine for the resistance of the Air according to Mr. Robinson | 3-13-6 |

| A Standard Barometer | 2-12-6 |

| The 5 Platonic Bodies | 1- 5-0 |

| A Cone dixsected | 0-12-0 |

| To Packing all the above | 2- 0-0 |

| "Peter Dolland | |

| The Acromatic Tlescope with a Triple Object Glass 3½ feet focus, two Eye Tubes for Astronomy & one for Day Objects | 15-15-0 |

| A best double microscope &c | 7- 7-0 |

| A Solar Microscope with Apparatus | 5-10-0 |

| The Reflecting mirror a true parallel Glass | |

| A 12 Inch Concave Mirror, a flat Mirror | 4- 0-0 |

| A 6 Inch Concave Mirror | -15-0 |

| 5 Lenses of different Sorts in Frames | 3-10-0 |

| 2 best Prisms | 3- 0-0 |

| A Water Prism | 2- 5-0 |

| A Set of Small Prisms in a Case | 1-11-6 |

| Two Specula on a Frame to shew a number of Reflexions | 1- 5-0 |

| 3 Parall: Glasses 2 Inch: Diam. for taking the Sun's Altitude in Mercury | 0- 6-0 |

| A Square Par: Glass 6 Inch: Diam. in a Frame | 1- 1-0 |

| An Object Glass for shewing the Rings of colors to be us'd with the Plane Glass | 1-11-6 |

| A Square Mahogany Tube with, an Object Glass & a Number of Eye Glasses to shew the Direction of the Rays of Light in Eye Glasses Packing the above | 0- 5-0 |

| "Edwd Nairne* | |

| £273-19-0 | |

| An Electrical Machine | 10-15-0 |

| A Glass Jarr | 2 -8-0 |

| 5 Glass Syphons | - 7-6 |

| A model in Glass to show the manner of Intermitting & Reciprocating Springs | 2-14-0 |

| 17 Capillary-Tubes | - 6-6 |

| 2 Glass Models of Pumps | 4- 4-0 |

| 2 Glass Parallel Plains | -18-0 |

| A Glass Jarr, for the Hydrostatic Balance, the Screw, wheel & Axle Compound & other Levers &Weights, Wedges & Weights; Pullies & Weights & ye 6th Mechanic Power, all fix on 2 Brass Pillars | 20- 7-0 |

| A Brass Circular Carriage | 3- 8-0 |

| A Mahogany inclin'd Plane wth a Quadrt which sets to any angle wth Scale & Nest of weights 164 oz Troy | 4-16-0 |

| Dr. Barker's Mill3 | 4- 4-0 |

| An Instrument to try the Force of falling Bodies | 3-17-0 |

| £332- 4-0" |

In 1817 a record noted that the room "for the apparatus" had been put "in complete order" and that "a Chemical Laboratory" had been constructed.86 In 1836 it was suggested that the "Classical School" (the Grammar School had been moved from its original location to the great Hall) be altered for the Chemical Laboratory and Philosophical rooms, which required flooring over some rooms, pine columns to support the floor, pulling down old work, and "moving the Benches and Furnaces out of the present Laboraty. " This was where the Chemical and Physical laboratory and lecture rooms were located when the building was destroyed by fire on February 8, 1859. The fire was thought to have started in the basement under the rooms (which had once been the Kitchen, and where wood was then stored), or in the Chemical Laboratory itself. Before it was discovered it had become too intense for anything to be saved from the northwest wing, and the apparatus, and library, which was then on the floor above it, were completely destroyed.87

The lecture room for the Professor of Moral Philosophy was in the room at the north end of the east front of the building; where it probably was by the middle of the eighteenth century — if not earlier — and on into the nineteenth century.88 This room will be taken up in more detail

23

THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY SHOWING THE "BRAFFERTON," THE MAIN COLLEGE BUILDING, AND THE PRESIDENT'S HOUSE, CIRCA 1840.

THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY SHOWING THE "BRAFFERTON," THE MAIN COLLEGE BUILDING, AND THE PRESIDENT'S HOUSE, CIRCA 1840.

From lithograph made in 1840 by Thomas Millington, son of John Millington, Professor of Chemistry and Natural Philosophy at William and Mary College, 1835-1848.

24

later, together with the Grammar School, the Hall, the Chapel, the Convocation Room or "Blue Room," and a room adjoining the "Blue Room," each of which is to be restored to as near its eighteenth century appearance as is possible.89

We have not been able to locate the room used for the Library in the eighteenth century, from the surviving records. The Rev. Hugh Jones stated (ca. 1724) that it was "without Books, comparatively speaking"; but added that it was "better furnished of late than formerly, by the kind Gifts of several Gentlemen; but yet the Number of Books is but very small." The 1729 transfer of the College from the surviving Trustees to the President, Masters and Professors, mentioned a "convenient chamber set apart for a Library."90 This might have been the room to the north of the "Blue Room," earlier in the century; but in 1773 the Library was apparently in a range of three rooms running north to south. As at present rebuilt, there are not three such rooms in a row on the first or second floors of the College. A 1773 record mentioned a new location for the infirmary, ordering that it occupy the room "on the South Side of the Library-Door"; and it was ordered at the same time that three students occupy "the Room on the North-Side of the Library."91 In 1837 it was decided that "the present Library might be moved upstairs with advantage"; and the Librarian was paid for his extra trouble in "moving the Library into the Upper South Room."92 The Library had about 3000 volumes at the time of the Revolution. The Librarian, usually a master or an usher in the eighteenth century, kept the key to the Library,93 and the Library was only open about once a week at specified times. Masters and Professors might keep a book out for six months; in 1792 students had to pay an annual fee of 10/- for the use of the Library, and could only take out one book at a time, to be returned to the Librarian "in the Council Chamber" within a month. He also had to deposit the value of the book taken out with the Librarian. By 1792, a student could only keep a book a fortnight. No rare and valuable books could be taken from the Library; and by or before 1829 no student could enter beyond the Librarian's counter, or take down any book from its place. The Librarian kept a record of the names, titles of books, and dates taken out. In 1830 the Library was open from 12 to 2 o'clock on Saturdays.94 When the building was burned on February 8, 1859, the Library was) in the room on the second floor over the northwest wing (the 25 original Hall wing), with the Chemical and Philosophical Laboratory and lecture rooms under it, and dormitories above it. The fire started in that wing. All the books were destroyed except a few not in the Library at the time. The Library had been enlarged, and then contained between seven and eight thousand volumes. It was described as having many rare old volumes, "in great part the gift of Kings Arch-bishops, Bishops, Nobles, Colonial Governors & Gentlemen," which, with "the exception of a few volumes in the hands of Professors & Students at the time" were all consumed.95

The Main Building of the College was in constant need of repairs in the first half of the nineteenth century. The College carpenter was kept busy around the premises, and additional work by brickmasons and plasterers was required almost every year. In 1817 President J. Augustine Smith reported that "there was not a single Lecture-Room properly fitted up in the College & the whole establishment was tending rapidly to ruin." The following year he reported that the interior had been "repaired with the exception of the Chapel," which would be "fitted up" in the course of the following summer.96 A good deal of damage was done to the College building, especially to the northwest wing, by a tornado in June, 1834, and it required expensive repairs.97

Some very extensive changes were made in this building a few years before the fire of 1859. In 1854 the Faculty decided that, "owing to the effects of time and hard usage, the part [of the College building] occupied by the students" was "in a condition hardly tenantable," and the building needed "little less than the entire renovation of the whole interior," at a probable cost of at least $10,000. The Visitors and Governors gave the Faculty permission to raise funds for this work by way of subscription; and they were successful enough in this to advertise for bids in April, 1856, for "taking down several Chimneys, cleaning and laying the brick — for framing and putting up several hundred yards of Partitions — for taking up, levelling and re-laying from fifteen to twenty thousand feet of Flooring, and for lathing and plastering from six to eight thousand yards" of wall, the work to be largely completed by the middle of September following.98 The College building was "repaired and altered so much that an old student would not know its interior," according to one newspaper account.99 Another account gave more details concerning the "improvements": The front portico 26 was widened to include a window on each side, and a new flight of steps to it was built "to take the place of the well worn ones" that had "performed their office since 1723" — [sic] — probably since 1716. The lecture rooms were to be painted and refitted "after the style of the chapel," and would all be on the first floor — the chemical and philosophical apparatus occupying the right wing (the original Hall). On the second floor "at the south end of the long hall" a society hall 22 feet wide, 40 feet long, with a 17 foot pitch, was constructed, and at the north end was a similar society hall of about the same dimensions. The "College Library Hall" was made "more convenient by an entrance at its side"; and only the "venerable 'Blue Room'" remained as it was, "still decorated with its historical portraits." The rest of the second floor was taken up with "convenient airy rooms for students." Two new stairways "broad and conveniently located," were built from the first to the second story. In the third floor, all the walls were pulled down and "the rude arches and corpulent chimneys places there by our ancesters" gave way to "less bulky rafters and chimneys"; the flooring was relaid, and the whole area was taken up "by larger and more convenient dormitories for students." The old belfry , or cupola, was replaced by a larger one.100

As already noted, the College building was destroyed by fire which started between two and three o'clock in the early morning of February 8, 1859. Everything was burned except a few books not then in the Library; and "the portraits the College records & Charter, which were fortunately in the Blue room," were also saved. An "illuminated copy of the Transfer" of 1729, and a treasured letter from General Washington accepting the Chancellorship of the College were destroyed. In the Chapel, where there was "little of value" that "could be moved"; the tablets which adorned the walls "in memory of the old worthies" were all "broken & destroyed, except the handsomest of all to Sir John Randolph," which was left partly standing — the professors hoping "to collect the fragments." The exterior walls, though standing, were "warped & cracked by the intense heat, all Chimnies and a portion of the interior walls" fell in the fire.101

The building was again erected on its original walls, and was completed in a remarkably short time, the

27

MAIN BUILDING OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY, 1859-1862. AS REBUILT ON ORIGINAL WALLS AFTER FIRE OF FEBRUARY, 1859, AND AS IT APPEARED UNTIL FIRE OF SEPTEMBER, 1862. (From lithograph printed by A. Hoen & Co. of Baltimore.)

28

celebration of laying its "cap-stone," on October 11, 1859. It was quite different in its exterior appearance from the building of ca. 1716-1859.102

MAIN BUILDING OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY, 1859-1862. AS REBUILT ON ORIGINAL WALLS AFTER FIRE OF FEBRUARY, 1859, AND AS IT APPEARED UNTIL FIRE OF SEPTEMBER, 1862. (From lithograph printed by A. Hoen & Co. of Baltimore.)

28

celebration of laying its "cap-stone," on October 11, 1859. It was quite different in its exterior appearance from the building of ca. 1716-1859.102

The College had about 60 students before the fire of 1859, it had 63 in 1860.103 In May, 1861, at the outbreak of the War Between the States, the College exercises were suspended; and the building was again used by the military, first as a barrack and then as a military hospital. The Confederate forces evacuated Williamsburg in May, 1862, and Federal troops then occupied Williamsburg. After a brief skirmish with some Confederate troops who entered the town on September 9, 1862, the College building again burned, being set on fire by soldiers of the Fifth Pennsylvania Cavalry. In this fire more was saved from the building: the charter, the seal of the College, some of the College records, and a number of the books. Most of the Philosophical apparatus, purchased after the fire of 1859, had been removed for safe-keeping, and was also saved. The exterior walls of the College were left in about "as good condition as they were after the fire of 1859: in fact … less warped and cracked." But the ruins of the building stood until the end of the war; and Federal soldiers, breaking into the vaults under the College Chapel, robbed them "of the silver plates attached to the coffins , and of whatever else of value they were found to contain." This vandalism was checked when it came to the attention of the military commander.104

A journalist who visited the College of William and Mary in January, 1868, noted that "although the halls of the College yet remain a painful monument to the violence of civil war, the Professors were conducting the exercises of the College in the spacious Brafferton hall," but had very few students.105 The third building to be erected on the remains of the original walls of the College was begun in 1868 and completed in the fall of 1869. Again, its exterior differed considerably from that of the ca. 1716-1859 building.106

The continuity of the College of William and Mary from the building designed by Sir Christopher Wren was preserved by the use of the original walls after each of the three disastrous fires of 1705, 1859, and 1862. An examination of the bare walls of the building during the extensive repairs of 1856 showed "traces of a general conflagration,"

29

THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY CIRCA 1869-1870 — SHOWING THE "BRAFFERTON," THE MAIN BUILDING AS REBUILT ON ORIGINAL WALLS AFTER THE FIRE OF SEPTEMBER, 1862, AND THE PRESIDENT'S HOUSE.

THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY CIRCA 1869-1870 — SHOWING THE "BRAFFERTON," THE MAIN BUILDING AS REBUILT ON ORIGINAL WALLS AFTER THE FIRE OF SEPTEMBER, 1862, AND THE PRESIDENT'S HOUSE.

(From photograph in the Coleman Collection, Colonial Williamsburg archives.)

30

indicating to those who viewed the walls then and the walls remaining after the fire of 1859, that the "walls were more injured by the fire of 1705 than by that of 1859."107 There were several attempts made, both before and after the fire of 1859, to move the College from Williamsburg to Richmond,108 but those who favored preserving this continuity were successful in preventing the move. The Gazette and Eastern Advertiser (Williamsburg : E. H. Lively, ed .) for September 21, 1859, noted that:

" … The past associations and historic connections of the old building have been preserved by the erection of the new building upon the old walls, which probably equal in strength and durability any in the country …"

The College of William and Mary has been noted for its impressive list of alumni in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries — although because of the loss of many of its records — the list is not complete The education received in the Grammar and Philosophy Schools prior to the reorganization of the College as a University in December, 1779, and in the new schools of Law, Moral Philosophy, the Laws of Nature and of Nations, fine Arts, and modern Languages then instituted, developed a large number of statesmen and other prominent citizens. In A Brief Retrospect of the Eighteenth Century published in New York in 1803, Samuel Miller wrote of William and Mary College:

"There is probably no College in the United States in which political science is studied with so much ardour, and in which it is considered so preeminently a favourite object, as this." [Vol. II , page 503.]

The Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg: J. Hervey Ewing, editor) of May 17, 1855, commented on the College as follows:

"In looking over the General Catalogue of this institution, which we printed a short time since, we find the names of many, distinguished in American history . No college in the Union can boast a more illustrious Alumni. We regret 31 that it is impossible to make a full list of the Alumni, but the catalogue contains the names of 2,591.

From 1720 to 1826, there are 1362 students recorded in the catalogue, of these: 3 have been Presidents of the United States (Jefferson, Monroe and Tyler). 1, the first President of the American Congress (Randolph.) 1, Chief Justice (Marshall.) 3, Signers of the Declaration of Independence, (Jefferson, Braxton and Harrison.) 1, Lieu. Gen. of the U. S. (Scott.) 3, Vice Presidents. 10, U. S. Senators, 8 Govs of Va, (one each of Maryland Missouri and Florida.) 4 Secretaries of State, 8 other cabinet officers, 2, Judges Supreme Court, 9 of the Court of Appeals, and 20 other Judges, 1 Speaker, 20 members of the House of Representatives, one President of the old Colonial Council, One Gen. and many officers in the Revolution, besides several Ministers and Ambassadors to foreign courts, and many individuals who distinguished themselves in the Conventions and Legislature of Va .

Surely old William and Mary 'like the mother of the Grachii, when asked for her jewels' can point to her 'children.'"

George Washington was never a student at the College, but he received his surveyor's commission from the College — Washington being appointed surveyor of the newly formed County of Culpeper in 1749. In 1788 the Visitors and Governors of the College appointed Washington its Chancellor.

The College of William and Mary conferred the degree of Bachelor of Arts after four years of successful study in the Philosophy School, and the degree of Master of Arts after seven years, according to the Statutes published in 1758. It also conferred the following honorary degrees in the eighteenth century — the dates and wording of the degrees being recorded in the surviving manuscript Journals of the President, Masters and Professors for 1729-1784 and 1817-1830: 32

- Benjamin Franklin, "Degree of A.M." April 2, 1756 .

- General Chastellux [Marquis de Chastellux] "Degree of Doctor of civil Laws" March, 1782.

- Dr. Jean Francois Coste [Chief Physician of the French Army] "Degree of Doctor of Physic," June, 1782.

- Thomas Jefferson, "Degree of Doctor of Law," December, 1782 .

- General Lafayette [Marquis de Lafayette] "Honorary degree of Doctor of Laws," October, 1824.

Notes on the rooms in the main building of the College of William and Mary which are now to be restored to their mid-eighteenth century appearance follow.

THE GRAMMAR SCHOOL ROOM

A Grammar School was the first school mentioned in the 1690 "Propositions" or proposals of the Clergy of Virginia for founding a College in Virginia, to consist of a Grammar School, a Philosophy School, and a Divinity School. The approved method of learning in "the most famous Universities" was first a classical education in a Grammar School, then the study "of Philosophy natural & moral," and lastly "of such Sciences as are to become the Business of the Students during the Remainder of their Lives";109 and Grammar Schools were associated with many English colleges. Before entering such a school, at the age of twelve or thirteen, a scholar must be able to read, write, know simple arithmetic, and be well "instructed in the Grounds of the Language."110 In the Grammar School he spent four to six years attaining proficiency in Latin, Greek, and a general "Classical Knowledge." Schools usually consisted of a Grammar-master, who was head master, and one or more assistant Masters or Ushers, depending on the size. The Grammar-master usually had a Master of Arts degree, and the Assistant-masters or Ushers were required to have at least a Bachelor of Arts degree.111

As has been noted, instruction in the Grammar School at the College of William and Mary began ca. 1694, before the first College building was completed, in a School-house near the site. The School-master, Usher, and scholars (probably between 25 and 30) moved into the College building late in 1700, and continued in it until the building was burned on October 29, 1705. The Grammar School was in a room to the north of the main entrance to the College building, and was doubtless furnished much as were similar school rooms in England. There were 29 scholars in the school in 1702, most of whom probably lived in the upper rooms or the dormitory of the building, and had their meals, or commons, in the Hall.112

After the fire of 1705, and until the College was rebuilt on its original surviving walls, the Grammar School was again operated in a School-house near the site of the College — possibly in the same one used circa 1694-1700. Funds were not immediately available, and the College was not rebuilt and ready for use until ca. 1718. It still consisted of only half of the quadrangle originally planned by 34 Sir Christopher Wren. Although there were some changes in this second building, the Grammar School Room was in the same place as before — to the north of the main entrance to the building and on the first floor. The room measured approximately 24 feet by 32 feet, with double doors at its south end, from the main entrance-hall, a fireplace and closet at its north end, four high windows on its east side, and two on its west, opening onto the piazza. This room was again furnished as were English school rooms of the period, with a desk for the Master, a desk or desks for the Usher or Ushers,113 and benches or forms around the walls of the room for the scholars, who were doubtless separated according to the forms or classes to which they belonged. There may have been an additional box or chest in this room, in which books, papers, and other supplies could have been kept, although the closet also served this purpose.114 There may also have been a "General Map of the World" hanging at the south end of the room, as there was in the 1695-1705 building.115 It is certain, from the English illustrations of school rooms that follow, that the type of furnishings used in such rooms changed very slowly.116

By June, 1716, the rebuilding had progressed far enough for the Visitors and Governors to write to Messrs. Micajah and Richard Perry in London for "Standing furniture for the Colledge Kitchen, Brewhouse, and Laundry," and a "bell of 18 inches Diameter at the Brimms for the use of the Colledge." They also wrote the Perrys for furniture for the "Convocation Roome," green broadcloth, a fire engine and "2 Doz: leather Bucketts with the Colledge Cypher thereon," and for books, paper, quills, inkpowder, penknives, etc. for the College clerk and the Indian school children. At that time the Visitors and Governors also agreed to purchase the "books and Globes which are proper for the Colledge Library at a reasonable price" from Arthur Blackamore, then Master of the Grammar School, who signified "his inclination to goe for England at the end of six months." The Visitors and Governors also resolved that "the bedsteads of the scholars be made of Iron according to the model prepared by Daniel Jones,"117 armourer in Williamsburg.

It is to be doubted that prior to the American Revolution there were ever more than 30 or 40 boys in the Grammar School, although at times there were between 70 and 35 80 students in the College, including the few Indians on the Brafferton foundation, and the students who had progressed to the Philosophy and Divinity Schools.118 It is probable that a few day students living in town added to the total attending classes at the College. It was not until 1729 that the College had its full faculty of six Masters or Professors: the Grammar Master, the two Professors of Philosophy, the two Professors of Divinity, and the Indian Master.119

The Grammar-master's position was not an easy one. As Mungo Ingles wrote circa 1704:

"It is nothing to be (all ye year long except in ye breaking up) Confin'd to College from 7 to 11 in the morning; & from 2 to 6 in the afternoon, and to be all day long spending ones Lungs upon a Compa. of children, who (many of them) must be taught ye same things many times over."120

Some comments by the Rev. Hugh Jones (who, as has been stated, was Professor of Mathematics at the College from ca. 1716-1721, and, for a brief time after the death of Mungo Ingles in 1719, also assisted the Usher in the Grammar School) may throw some light on the activities of the Grammar Scholars, as do the Statutes of the College, which were finally drawn up in 1727.

At the time of his writing (ca. 1721-1724) the Rev. Mr. Jones stated that the College was "a College without a Chapel, without a Scholarship, and without a Statute," and its Library was "without Books, comparatively speaking." Chapel services were held in the Hall. Jones recommended that the Grammar scholars continue to "be boarded and lodged in the Dormitory, as they are at present"; that they be "two Years under the Care of the Usher, and two more under the Grammar Master; and by them instructed in Latin and Greek"; and that "during these four Years, at certain appointed Times they should be taught to write as they now are in the Writing-School," and that the Writing Master should also "teach them the Grounds and Practice of Arithmetick, in order to qualify such for Business, as intend to make no farther Progress in Learning."

36He suggested that out of the Grammar School, five "Scholars upon the Foundation" [or scholarship students] should be elected each year by the President and Masters and Professors, to have "their Board, Education, and Lodging in proper Apartments gratis and should also be provided with Cloaths and Gowns, &c. after the Charter-House Method." These scholars should be instructed "in Languages, in Religion, in Mathematicks, in Philosophy, and in History, by the five Masters or Professors appointed for that Purpose." He added that the Scholars, including Commoners from outside the College [or day scholars], should "be obliged to wear Gowns, and be subject to the same Statutes and Rules as the Scholars; and as Commoners are in Oxford." "Town Masters" could teach the scholars such things as "Fencing, Dancing, and Musick."121

Hugh Jones also suggested that a "Body of Statutes … be directly formed and establish'd by the Visitors, President, and Masters";122 and this was accomplished before the Transfer, in 1729, of the College from the Trustees to the President, Masters and Professors. Statutes dated London, June 24, 1727, were signed by President James Blair and Stephen Fouace, surviving Trustees for the College, and approved by the Visitors and Governors, and by the Chancellor of the College, then the Archbishop of Canterbury. They were printed in Latin and English by William Parks, printer of Williamsburg in 1736, and again printed in Williamsburg by William Hunter in 1758.123 The only changes in the Statutes of 1727 and 1758 concerned salaries. Concerning "The Grammar School," to which "belongs a School-Master; and if the Number of Scholars requires it, an Usher," the School-Master receive a yearly salary of £150 Sterling and 20 shillings a year from each scholar, and the Usher five — the Usher's salary to be £75 Sterling. From the "poor Scholars, who are upon any charitable College Foundations," neither Master nor Usher received fees. The Usher was to be "obedient to the Master in every Thing"; and special care was to be taken of the scholars' "Morals," that none of them "presume to tell a Lie, or curse or swear, or talk or do any Thing obscene, or quarrel and fight, or play at Cards or Dice, or set in to Drinking, or do any Thing else that is contrary to good 37 Manners." As to the teaching in the school:

Besides examinations for scholars hoping to become "Foundation Scholars," scholars in all the schools were to be often examined by their Masters and Professors in the presence of the President, and also examined by the President "apart from their Masters, that both Masters and Scholars may be excited to greater Diligence in their Studies." 125"In this Grammar School, let the Latin and Greek Tongues be well taught. As for the Rudiments and Grammars, and Classick Authors of each Tongue, let them teach the same Books which by Law or Custom are used in the Schools of England. Nevertheless, we allow the School-master the Liberty, if he has any Observations on the Latin or Greek Grammars, or any of the Authors that are taught in his School … [to] dictate them to the Scholars. Let the Master take special Care, that if the Author is never so well approved on other Accounts, he teach no such Part of him to his Scholars, as insinuates any thing against Religion and good Morals.

…

On Saturdays and the Eves of Holidays, let a sacred Lesson be prescribed out of Castalio's Dialogues, or Buchanan's Paraphrase of the Psalms, or any other good Book which the President and Master shall approve of, according to the Capacity of the Boys, of which an Account is to be taken on Monday, and the next Day after the Holidays.The Master shall likewise take Care that all the Scholars learn the Church of England Catechism in the vulgar Tongue; and that they who are further advanced learn it likewise in Latin.

Before they are promoted to the Philosophy School, they who aim at the Privileges and Revenues of a Foundation Scholar, must first undergo an Examination before the President and Masters, and Ministers skilful in the learned Languages; whether they have made due progress in their Latin and Greek. And let the same Examination be undergone concerning their progress in the Study of Philosophy, before they are promoted to the Divinity School. And let no Blockhead or lazy Fellow in his Studies be elected.

If the Revenues of the College for the Scholars [scholarship students], are so well 38 before-hand, that they are more than will serve Three Candidates in Philosophy, and as many in Divinity, then what is left let it be bestowed on Beginners in the Grammar School."124

There were three terms in the Grammar and Indian Schools: The Hilary term began "the First Monday after Epiphany" [Epiphany —January 6th] and ended "on Saturday before Palm-Sunday" [Palm-Sunday, the Sunday before Easter]. The Easter term began on "Monday after the First Sunday after Easter," and ended the "Eve of the Sunday before Whit-Sunday" [Whitsunday — the seventh Sunday and fiftieth day after Easter]. The Trinity term began on "Monday after Trinity Sunday" [Trinity Sunday — the Sunday next after Whitsunday] and ended December 16th.126

Immediately following these Statutes in the 1758 edition were added several regulations of the Visitors and Governors: All Masters, Professors, and Ushers must "provide Firing and candles for their Chambers, at their own Expence"; must pay 50-shillings a year for their washing, if done in the College; and, if they kept "waiting Boys" at the College they must pay £5 a year for their board. If they desired "hot Suppers," they must provide them at their own expence; and "one of the Masters or the Usher," must always be present "with the Boys at Breakfast and Supper."127