Architectural Report on the Palace Refurnishing Project

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 248

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

ON THE

PALACE REFURNISHING PROJECT

Department of Architectural Research

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

September, 1983

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

This report documents architectural alterations made in association with the refurnishing of the Governor's Palace between January and April of 1981. These alterations were effected on the initiative of the Department of Collections, and in close collaboration with its staff. In working out the details of such changes, the architects were, of course, guided by a commitment to as accurate a portrayal of 18th century life in the Palace as was reasonably possible. In as far as the first and most important commitment allowed, a determined effort was made to preserve the integrity of a 20th century building, having its own intrinsic merit and historical importance. These, then, were the principles which guided decisions outlined in the following chapters.

Arms Arrangement - Hall, Passage and Stair

In accordance with documentation indicating the presence of numerous arms in the hall of the Governor's Palace throughout the 18th century,1 it was determined to display a large number of weapons in the hall, passage and stairwell, paralleling surviving 18th century arms arrangements in England. Although no mention of the passage or stairwell appears in documentation of the Palace arms, the curatorial staff opted to install displays in these areas, arguing that it would have been difficult if not impossible to confine such displays to the hall alone. Arms arrangements at Chevening in Kent, England provide precedent for this method of disposition. (See fig. 1).

As part of the arms arrangement for the Palace, the curators settled upon an oval of 64 muskets to be mounted on two concentric walnut moldings, affixed to the ceiling of the hall. Originally, this assembly was to be secured to the ceiling by drilling into the structural concrete "pan" slab from below, and bolting through the moldings with threaded rods, seated in lead shields. However, when it was learned that the entire assembly was to weigh more than 600 pounds, this scheme was abandoned. Ultimately, it was decided to take up the flooring of the room above, and drill downward, hanging the guns and mounting assembly on rods bolted through the slab.

Because the pan system of the slab was actually built 5" off the center shown on the original working drawings, several holes had to be drilled through the entire depth of the stems or ribs. In two instances where reinforcing steel was encountered, drilling was stopped, and alternate holes were drilled in from the bottom on slightly different centers.

The arms arrangement conceived for the Palace were based upon similar installations at Chevening House, already mentioned, and on watercolor drawings by one John Harris of an arms arrangement at Windsor Castle or perhaps Hampton Court. (See fig. 2). This latter precedent is particularly appropriate in the light of St. George Tucker's early 19th century remarks comparing the arms arrangements of the Palace and the Tower, arrangements which Harris is known to have laid out.2

3Hardware for hanging the various types of weapons at the Palace was detailed so as to damage existing woodwork as little as possible. Walnut strips were affixed to the side faces of pilasters to receive the large wrought staples used in mounting the hangers or swords. Spacing of the muskets was adjusted to avoid screwing hardware into the feathered edges of the panels. This is especially evident in the passage downstairs.

Flagstaff Brackets - Hall

The list of standing furniture in the Entrance Hall of the Governor's Palace mentioned among other things, "Arms & Colours."3 Because weapons documented as being in the Hall belonged to the crown and would not have been listed in the inventory, it is believed that the term "Arms" referred to a coat-of-arms similar to that now in position above the fireplace.4 The conjunctive listing of this coat-of-arms and the "Colours" seems to suggest a close physical relationship between them. Reasoning thus, the curatorial staff elected to place the coat-of-arms in its present position over the fireplace, and to group the colors over the archway leading into the passage. Their fan-like arrangement is based on the study of similar groupings at Blenheim Palace and Hatfield House.5

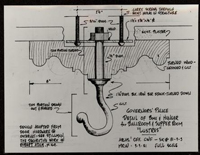

No appropriate model after which to design mounting hardware could be located. Because of the tremendous "moment" or twisting force produced at any cantilever connection, it was decided that the three flagstaffs should be (and would have been) supported at both ends. Initially, the use of wire was envisioned for supporting the upper ends of the staffs. However, Mr. Gusler expressed the belief that wire was not in general use in 1770.6 It was therefore decided that light wrought iron hangers should serve this purpose. These were designed so as to use the oval walnut moldings on the ceiling as a mounting surface. The center hanger cantilevers outward some distance to receive the head of its corresponding staff and is consequently heavier than the flanking hangers. It was necessary to create a "jog" in this center hanger, since it was to fall on the center line of one of the muskets. (See fig. 3).

Over the archway, a small wooden bracket was affixed with blue, dome-headed screws to the bottom plan of the architrave, having three holes drilled on angles to give a slight inclination to the staffs and to "fan" them over a 60° arc. A light iron plate was nailed across the bracket face, providing a lip to "hook" on notches cut into the staffs, just above their brass ferrules.

5The surface available for mounting the bracket determined its size. It's curved face conforms to the arc defined by the staff ends, and the ogee curves at either end diminish the bracket depth so as to provide attachment surfaces. The use of dome-headed screws for affixing this bracket to the woodwork parallels the use of such screws in attaching walnut strips to the pilaster faces for display of hangers or swords. Mr. Gusler observed that these dome-headed screws are frequently found in pieces of furniture dating from the early 18th century. Because installation of the arms and colors is believed to date from about 1711,7 the use of these early-type screws is a logical choice. Their blued finish is consistent with the "military" character of the weapons and colors.

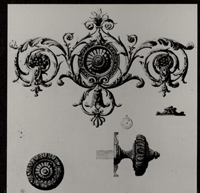

Carved Medallion - Hall

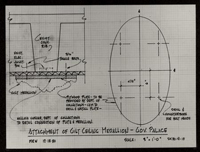

Based on similar examples still in place at Chevening in Kent, England, a carved and gilt medallion was centered in the oval of muskets on the hall ceiling. So as to have no visible fastenings, a base plate for this medallion was fabricated and installed so as to avoid the stems of the pan slab above the plaster ceiling. Mr. Gusler let fastening devices into the back of the medallion which engaged metal pins in the base plate when slid along its main axis. (See Fig. 4)

Silver Cabinet - Pantry

The 1770 inventory of Governor Botetourt's personal estate listed numerous articles of silver being kept in the Pantry at the time of his death.8 It was necessary, of course, that this silver be secured in the day-to-day operation of the Governor's household. Because none of the furnishings listed in the Pantry seem to have been suitable for such a task, it was concluded that some built-in feature had served this purpose.

When doors, windows, shelving and an enlarged visitors' area were taken into account, the southeast corner of the Pantry emerged as the only practical location for such a fixture. Initial schemes for this fixture were developed along the lines of a built-in dresser, having drawers and cupboards below a work surface. Consultation with the curatorial staff made it clear, however, that the inventory contents required more space than this sort of arrangement could provide. A new design was therefore modeled along the general lines of a large press, its dimensions based on the quantity of silver to be in storage.

The free-standing press form is perhaps not the best way to portray a built-in fixture. This form was adopted, however, out of a desire that the existing paneling be disturbed as little as possible. The construction joint which bestows a "built-in" status on the cabinet therefore occurs at the rear of the fixture. The stopped chair rail and red paint on the cabinet, matching that on the paneling would have further suggested a built-in cabinet to the person making the 1770 inventory. From a practical standpoint, a case piece of this sort lent itself more readily to the installation of a green baize lining, called for by the curators. Such linings for silver cabinets are mentioned in the accounts of Thomas Chippendale.9

Construction details for the upper and lower cases were developed in consultation with curatorial staff members Wallace Gusler and Sumpter Priddy. Molding profiles were borrowed from a 8 number of sources. The cornice molding was adopted from drawings of an eighteenth century English desk and bookcase, published in E. J. Warne's Furniture Moldings, plate 10. This profile was of sufficient depth to effectively "finish off" the piece while maintaining a relatively modest projection - a crucial requirement since clearances between the architecture and the installed cabinet were to be extremely small. The base molding repeats the profile used under the window seats in the Pantry. Muntin profiles and detailing of the glazed doors parallel a Virginia desk and bookcase, formerly on exhibit at Wetherburn's Tavern.10 Initially, these doors were to be paneled as in the lower section, based on the idea that security, and not display, had been the governor's overriding concern.11 The curatorial staff argued, however, that display of the silver was desirable from a modern, interpretive standpoint. Since the cabinet was to stand literally inside the new area cordoned off for visitors, it was absolutely necessary that the doors of the cabinet be kept locked at all times. Glazed doors were the only alternative if the silver was to be seen by visitors. (See fig. 5).

In order to create the impression of a built-in piece, the cabinet back was detailed in such a manner as to fit snugly against the paneling of the south wall without disturbing it. When workmen began to install the piece, it was found that a last minute addition of battens to the cabinet back prevented the assembly from going all the way to the wall. Mr. Gusler explained that it has been necessary to add these battens to stiffen the cabinet back while it was being lined with baize. In the field, with installation partly completed, it was decided to proceed without removing the battens. This decision was based on the following considerations:

- 1)Removal of the battens might damage the baize lining of the cabinet.

- 2)Scribing the battens to go around the panel molding would have been extremely difficult, and would have required cutting through the nails fastening them to the cabinet back.

- 9

- 3)The junction of the cabinet with the wall would not be visible to most visitors.

- 4)The extra ½" of cabinet projection created by the battens helped to hide more effectively an electrical conduit installed to deliver power to a spotlight on top of the cabinet.

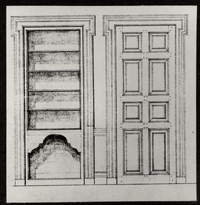

"Closet next the fire" Pantry

The governor's inventory posed still another problem with regards to the architectural arrangements of the Pantry. Listed among the contents of the Pantry was "l iron chest in the closet next the fire."12 Initially, the curatorial staff expressed the belief that this feature was a walk-in affair, reasoning that the "iron box" was probably a heavy chest, dragged in and out of the closet along the floor. However, accounts subsequently located in England indicated that this box had been shipped to Virginia in a desk drawer.13 Other items in the closet suggested that it may have been a fairly modest receptacle--perhaps let into the brickwork to the right of the fireplace.14 Access to this sort of receptacle could have been achieved through a hinged door in the paneling similar to surviving examples throughout the colonies.15 Because the reconstructed Pantry was finished with raised paneling and roll moldings, it was considered impractical to cut such a door into the existing woodwork. Furthermore, no surviving example of a door cut into raised paneling of this sort could be located. It was therefore concluded that the entire panel below the chair rail would be treated as a "jib" door, similar to a series of hinged panels in the Library of Chicheley Hall in Buckinghamshire, England. (See figs. 6 & 7). Because the curators did not envision exhibiting the contents of this closet, the door was made non-functional, thus minimizing disturbance of existing woodwork.

The inventoried contents of the closet were relatively valuable and it is likely that they were kept locked up.16 Initially, this likelihood presented a problem since the keyhole for any typical cabinet lock would fell squarely in the middle of the panel molding. However, an example of this kind of arrangement was located in a second floor chamber at Battersea in Petersburg, Virginia. This example provided the basis for treatment of the jib door in the Pantry.

Buffet - Dining Room

The addition of a built-in side-cupboard in the Dining Room of the Governor's Palace was predicated on the following logic:

- 1)A 1710 "Proposal for Rendering the new House Convenient as well as ornamental" recommended the purchase of "one Marble Buffette or Sideboard wth a Cistern & Fountain" to be placed in the "lower Apartments" of the Governor's Palace.17

- 2)While the above document probably referred to a Buffet of the type discussed by Mark Girourd and Sir Peter Thornton, it appears that a marble-topped, side board table was purchased for the Palace instead. An eighteenth century inventory of standing furniture at the Palace mentions among other things, "one Side Board wth Marble Slab" in the Dining Room.18 Similarly, a listing of standing furniture sent to Richmond in 1779, mentions "l marble sideboard."19 Another such list made about the same time refers simply to a "Marble Table."20 Thus, the "Marble Buffette or Sideboard" purchased by the Colony in accordance with the 1710 proposal is believed to have been a side table with a marble top.

- 3)The "Bowfat" mentioned in the 1770 inventory of Governor Botetourt's possessions, appears to have been a separate and distinct entity from the sideboard table purchased by the colony. According to Mr. Hood, no early eighteenth century piece of furniture which could be properly called a side-board was capable of containing the contents 13 ascribed to the "Bowfat," in Governor Botetourt's inventory.21

- 4.The inventory heading, "In the Bowfat," suggests that this item was some sort of built-in arrangement, since all other headings in the inventory refer

to architectural features:

In the front Parlor : In the Closet ; In the Hall and Passage ; Plate in Pantry ; In the Storerooms ; In the Vault , etc.

- 5.Significantly, neither of the inventories list the Bowfat individually as part of the furnishings. The inventory of standing furniture enumerates only the "side Board wth Marble Slab" (which we have seen could not contain an extensive assemblage of glassware and ceramics) while the Botetourt inventory lists only the contents

"In the Bowfat" as belonging to the Governor--not the Bowfat itself. Elsewhere in the inventory it is quite clear when a piece was to be included with its contents as a part of the Governor's estate. In his Lordship's Bedchamber we find:

1 Large Walnut chest of draws containing his Lodp's Linnen, Gloves, Stockgs, & C ...

In the Middle Room are listed:2 Mahogy cloaths presses wth apparel,

That the Bowfat fails to appear as a part of the furnishings suggests again that it was a built-in feature.

2 snuff boxes 1 small ivory box & the

Seal of the Colony ... - 14

- 6.Further evidence of this appears in a 1720 estimate detailing the expected cost of finishing the Governor's House . Included in this estimate was a charge for "4 yds. of [paint] on The Side Board Shutter."22 There is no reason for this item to have appeared in the estimate unless the "Side Board" was part of the architecture. In some cases, the term "Side Board" appears to have connoted a built-in feature. In the building accounts for Hampton Court Palace, we find estimates for building the "King's Sideboard" which includes charges for brickwork, paving, paneling, etc.23 Obviously, this was an architectural feature--seemingly a small room. Significantly, the English Dialect Dictionary defines "buffet" as "a little apartment separated from the rest of the room, for the disposing of china and glassware."24 Thus, the terms "buffet" and "side-board" seem to have been interchangeable in connoting an architectural arrangement for the storage of glassware, etc.

- 7.On the basis of these facts and deductions, we believe that the 1720 reference to a "Side Board" and the 1770 mention of a "Bowfat" refer to the same built-in architectural feature.

- 8.Thomas Jefferson's measured plan of the Palace shows no buffet in the Dining Room. (See fig. 8). Available evidence suggests however, that he hastily drew up this plan as a basis from which to prepare a number of remodel ling studies. Jefferson's finished plan for Barboursville shows the location of a proposed buffet--but reveals nothing of its form or design. (See fig. 9). It is thus reasonable to suggest that such a feature might have been omitted altogether from his preliminary sketch of the Palace floor plan.25

- 9.The above considerations led to the decision to re- [deleted]

- 15

- 10)Based on a study of pictorial sources, archaeological evidence and Jefferson's dimensioned plan, it was decided to place this buffet to the left of the fireplace.

- a)Eighteenth century views and surviving examples suggested that this was a common arrangement (see fig. 10).

- b)The evidence suggested that there was once a doorway at this point, opening into what is now the Parlor closet.

- 1.Comparison of the foundation measurements with Jefferson's dimensioned floor plan revealed that only a 6" thick partition could have separated the Dining Room and Parlour closet, whereas the foundation indicated there should have been a masonry wall nearly 3 feet thick.

- 2.Evidently there was an opening in the transverse masonry wall running across the building at this point.

- 3.Efforts expended in the inclusion of such an opening could hardly have been justified by a few extra square feet of closet space. This opening must have been for a door.

- c)A door in this location, would have permitted access to the Parlor from the Dining Room. Such a connection would have been quite logical in the eighteenth century. Mark Girourd points out that it was customary for the ladies to withdraw to a separate room for tea after dinner, leaving the 16 men to drink in the dining room.26 Significantly tea equipage in Virginia inventories most frequently appears in parlors.

- d)The insertion of a buffet provides a likely scenario for closing off such an opening some years after the Palace had been occupied. Several facts seemed to support the idea that this Dining Room buffet was an alteration:

- e)Based on this line of reasoning, the "Bowfat" in the Palace Dining Room was designed to portray an original door opening to the left of the fireplace, closed off by the insertion of a buffet early in the eighteenth century (see figs. 14 & 15).

- 11)Detailing was developed in accordance with this concept.

- An "original" door opening was created to match other existing doors.

- Architraves matched those of the door leading into the passage in profile, and in the projection of its "ears" or crossettes.

- Door panel moldings facing the Dining Room matched those on the door leading into the 17 passage. Moldings facing into the buffet matched those on the interior face of the Parlour closet door.

- English and American buffets were studied to identify examples of shelving arrangements set within architraves which extended to the floor (see Appendix II). A listing of such examples includes:

- Brice House; Annapolis, MD

- "Wayne House," PA

- Verplanck Room, Metropolitan Museum

- Mount Pleasant; Philadelphia, PA

- The Old Manse; Concord, MA

- Queen Anne Bedroom, Winterthur Museum Araby, MD

- "Potts House," PA

- Warner Place, MD

- Readbourne Stair Hall, Winterthur Museum "Hope Lodge," PA

- "Clifton," MD

- Chinese Parlor, Winterthur Museum

- Benjamin Waller House; Williamsburg, VA

- Cedar Grove, PA

- Powell House; Philadelphia, PA

- "Woodford," Philadelphia Museum

- Frampton Court (possibly an addition)

- Queen Anne Dining Room, Winterthur Museum

- Whitby Hall, Detroit Institute of Arts

- Hogarth's "Tartuff's Banquet"

- Ormley Lodge

- Metropolitan Water Board's "New River" Office

- Unidentified example published in Warne's Furniture Molding's

- An "original" door opening was created to match other existing doors.

The Frampton Court example was adapted as a general prototype for the following reasons:

- a)It appeared to be an addition--inserted into a former doorway.

- b)It assimilates what appears to be a number of typical English features.

- c)Its use would continue the tradition of prototypes selected from Tipping's English Houses for use at the Palace.

The Frampton Court example had a section of shelving above the level of chair rail and had an opening below framed by a curvilinear skirt. The Ormley Lodge Buffet, the free standing buffet at King's Weston, and the example engraved by Hogarth all follow this general form (see figs. 16 - 19).

The openings of the Frampton Court buffet were set into a planar surround which was in turn set into the door opening. The Ormley Lodge example follows this same general form, if envisioned without its ornamental moldings and details. At Cedar Grove in Pennsylvania, and at the Waller House here in Williamsburg, the actual openings are once again cut into a planar surface, which is in turn inserted into a door opening (see figs. 12 & 20). These examples suggested a similar treatment for the Palace buffet. After some consideration of how an eighteenth century carpenter might have solved the problem, actual construction details were developed. Because the buffet was to be considered 19 an alteration, - an afterthought, it was to be simplified somewhat over its English counterparts. The shelving section was thus given a flat back and head, thus resembling a relatively simple section of book shelving, joined to the rear of a surround. The extra space afforded by this arrangement over a semicircular niche, just allowed the inventory contents to fit their "'container."27 This concern for space precluded use of "scalloped" shelving which appears frequently in surviving examples. The depth of the receptacle was determined by the diameter of "2 large enamd China bowls" selected by the curators in accordance with the Botetourt inventory.

The general character of the skirted opening was inspired by the examples at Frampton Court, Ormley Lodge and by the Hogarth print. Its geometry, however, is based specifically on the front door panels at "Four Mile Tree" in Surry County, Virginia. A similar configuration also appears in the skirt of a Virginia high chest base photographed by Singleton Moorehead in the early years of the restoration28 (see fig. 21). Door hardware--including iron hinges and a brass rim-lock with drop handle, was selected to match existing hardware in the Dining Room.

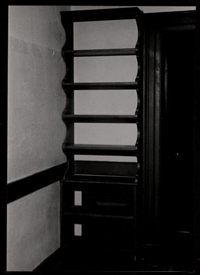

Removal of Shelving & Curtain Rod - Powder Room

Prior to refurnishing of the Governor's Palace, the space identified as the "Powder Room" in the Botetourt Inventory had been used as a storage area. At some point, it had been provided with a set of built-in shelves. Because nothing in the inventory suggested the presence of such shelving, this fixture along with an existing wooden curtain rod and bracket were removed from the space to make way for articles based on the inventory.(fig. 21a).

Wallpaper - Ballroom

Although correspondence indicates that the architects originally envisioned the use of a plain blue wallpaper in the reconstructed Ballroom, no such paper was ever installed.29 From Joseph Kidd's 1770 account for mending wallpaper, it is clear that the Ballroom was papered.30 Moreover, a Robert Beverley letter of 1771 suggests that this paper was plain blue, bordered with strips of gilt leather.31 This hypothesis is confirmed by the mention of gilt leather strips intended for the Supper Room, in the inventory of Governor Botetourt's estate:32 evidently, Botetourt was intent on decorating the Ballroom and Supper Room en suite with plain papers and gilt borders.

Guided by certain items listed in Botetourt's personal accounts and estate inventory, the curators were able to accurately reconstruct the methods used in Lord Botetourt's papering of the Ballroom. Eighteenth century documents describe this process in some detail, thus bringing together a series of seemingly unrelated objects mentioned in the Governor's inventory and personal accounts:33 "Oznabrigs" and cartridge paper to provide a smooth, reinforced mounting surface;34 two reams of elephant folio paper to be pasted in separate sheets on the wall; Blue Verditer, Prussian Blue, and "Whiteing" to color the paper; and gilt "Gooder oun" strips to border it.35 Because the above pigments could have produced any number of different blues, a fragment of plain blue wallpaper from Osterly Park was consulted in the mixing of documented colors. Sheet arrangement and the treatment of joints follows a surviving example of eighteenth century plain papering from Denmark.36

Cornice Revisions - Ballroom

Shortly before work on the Palace was to begin, the Department of Collections requested certain revisions in the Ballroom cornice. Soon after completion of the Palace in 1953, this had been revised to "break out" over the windows in such a manner as to form a "valence" for draperies.37 A review of pictorial and documentary sources failed to reveal an 18th century precedent for this sort of arrangement. Because there were to be no draperies in the Ballroom (in accordance with the inventories), the returns of these cornice sections were shortened so as to bring them back flush against the wall - as originally completed in 1934. (fig. 21b).

Electrical Work - Ballroom

Besides the revision of various decorative finishes, nine 110V convenience receptacles and a humidity and temperature control device were installed in the Ballroom wing. This latter device was chased into the north wall of the Ballroom to the right of the Supper Room door. The new control system provides a more stable environment in order to minimize the deterioration of those 18th century objects exhibited in the building.

Additionally, a 200A service line and receptacle were installed in the 1st floor room beneath the main stair. A 3" conduit for this line was brought in through the plenum room in the northwest corner of the cellar, and carried up through the vault. Although this area is not visible to the public, the conduit was run over the top of the door so as to be as inconspicuous as possible. This line provides power for lights used in filming, etc.

Ceiling Bosses for Chandeliers - Ballroom and Supper Room

For installation of new lustres in the Ballroom and Supper Room, the curators envisioned the use of gilt bosses from which to hang supporting brass chains.38 Details were thus developed for these bosses, and all necessary connecting hardware. Because the lustres were known to have been acquired by Governor Botetourt, shortly before his departure from England in August of 1768,39 it was decided that the character of the bosses should reflect the period around 1770. Accordingly, a door escutcheon designed by Robert Adam for Osterley Park and pictured in Damie Stillman's Decorative Work of Robert Adam, plate 163, was selected as a model. (See fig. 22 & 23.) In the writer's view, the resulting effect is not satisfactory. The thickness of the boss needs to be reduced and the curves of its profiles flattened out somewhat, if a "neo-classical feeling" is to be achieved.

Stovepipes Ballroom and Supper Room

Documentary evidence firmly indicates that the Ballroom wing of the Governor's Palace was built without fireplaces. Jefferson's plan showed no provision for heating in the rear addition, nor was any trace of fireplace construction evident in the scant architectural remains uncovered by archaeologists in 1930. It seems that cast iron stoves rather than fireplaces were employed in heating the Ballroom wing. The 1770 Botetourt inventory listed "1 large Dutch stove" among the Governor's effects in each of the wing's two rooms.40 When in 1781 the Palace was appropriated for use as a military hospital, Quartermaster General Timothy Pickering wrote to Governor Nelson, requesting that "those [stoves] formerly belonging to the palace be sent from Richmond, as there [are] three rooms at the palace destitute of fireplaces."41

Until recently, the means by which such stoves were vented remained a puzzle. As a result, stoves and flues had been omitted altogether in the reconstructed Ballroom wing. Recently, however, research conducted by the curatorial staff in connection with Lord Botetourt's "Dutch Stoves" turned up an itemized bill for a stove purchased by the Divinity School at Cambridge which included a charge for a "window plate." This document suggested then that such stoves were sometimes vented through windows. In support of this contention, the curators produced a print of Independence Hall, clearly showing such an arrangement (See fig. 24). The evidence presented by this bill is all the more compelling since it was rendered by Abraham Buzaglo, the manufacturer who provided Botetourt's stoves for the Palace.41a

Reasoning that such stoves would have been treated as formal decorative elements, the curators opted to center them on the side elevations of the Ballroom and Supper Room. While this arrangement 26 allowed the Ballroom stove to be vented through a window, the Supper Room stove was necessarily vented through the wall between the windows.

In order to avoid the complications arising from a complete penetration of the wall, the interior stovepipe in the Supper Room goes through the plaster but no further. In a similar manner, the "window plate" used with the Ballroom stovepipe has no actual opening. As of this moment the corresponding exterior stovepipes have not been put in place although hardware for their installation has been fabricated. (See fig. 25). Because no 18th century prototype for such hardware has been located, its design, arrived at through consultation of curatorial, architectural and craft personnel, was made as simple and straightforward as possible.

As installation of the interior pipes was about to begin, Ms. Gretchen Schneider of the Department of Research suggested that the stoves would have been located differently owing to their effect on the usable space of the room. Ms. Schneider pointed out that the stove, in its present location, would have interfered with the circle customarily formed by ladies and gentlemen observing the dance of couples at a ball or assembly. Mr. Gusler, however, expressed the belief that the circle had fallen from favor by Governor Botetourt's time. Mark Girourd places the date for the disappearance of the circle around 1780.42

It was decided to go ahead with installation of the stovepipes, based on the following considerations:

- 1.The conspicuous absence of stovepipes made some immediate action desirable.

- 2.Ms. Schneider's assertions were based, primarily, on "impressions" formed during the course of her work. Owing to her involvement with other projects, a thoroughly researched and documented statement of her point of view could not be expected in the near future.

- 27

- 3.Installation of the pipes involved relatively little disturbance to the architecture and was therefore easily subject to change should future information warrant it.

Although Ms. Schneider is no longer with the Foundation, her observations on this matter should be pursued.

Roll Shades - Supper Room

The inventory of standing furniture at the Palace listed no window coverings in the Supper Room per se. In the "3rd [storeroom]" however, "6 Spring Blinds" were mentioned.43 Because this reference matches the number of windows in the Supper Room, the curatorial staff opted to provide the room with the sort of blinds mentioned in the inventory. Old documents suggest that valences for these blinds were essentially "boxes" within which the rolling shade was suspended.44 Owing to the close fit of shades obtained for the Palace, this sort of arrangement was not feasible. As an interim measure, a valence or baffle was designed, consisting of a simple fascia hanging in front of the blind. These blinds and valences are to be re-designed on the basis of an eighteenth century example recently found by Mr. Hood in the Duke of Beaufort's muniments room at Badminton, Gloucestershire, England. Any new scheme for these blinds should include authentic mounting hardware, since it is virtually impossible to hide modern hardware, owing to the angle at which it is viewed from below.

Removal of Chinese Wallpaper - Supper Room

Removal of Chinese Wallpaper from the Supper Room was one of the most visible changes effected in the entire building. Having considered the various arguments for and against retaining this paper in the newly refurnished Palace, the Program Planning and Review Committee recommended its removal. Several important facts should be kept in mind regarding this decision:

- 1)The Chinese wallpaper in the Supper Room had no basis in the historical evidence bearing specifically on the Palace.

- 2)It's installation was due largely to the personal influence of R. T. H. Halsey of the Metropolitan Museum.

- Halsey located the paper and brought it to the attention of officials in Williamsburg, suggesting that it be used in the Palace or the Capitol.45

- Halsey mentioned that William Buckland had created a "Chinese" room for George Mason at Gunston Hall.46 (See fig. 26).

- Halsey attempted to tie Buckland to another "Chinese" decorative scheme at Honington Hall in England.47 (See fig. 27).

- Halsey's guide book to the Met's period rooms, The Homes of Our Ancestors, showed two mid-Georgian American Rooms hung with Chinese and Chinoiserie papers--one of them an imaginary "Alcove" at Gadsby's Tavern in Alexandria. These rooms undoubtedly created the impression that Chinese papers were used in America as a matter of routine.48 (See figs. 28 & 29).

- 30

- Thomas Waterman, the Supper Room's designer, owned a copy of Halsey's guide book.49

- Waterman seems to have subscribed to Halsey's theory that William Buckland did the Chinoiserie woodwork at Honington Hall, since he repeated this theory in his own book, The Mansions of Virginia."50

- It appears then the Supper Room scheme resulted more from aesthetic preference and the force of Halsey's personality than from any hard evidence of what would have been a likely treatment for such a space.

- 3)Recent research reveals the genuine Chinese papers were rarely used here in America during the mid-eighteenth century .

- 4)More importantly, recent scholarship reveals that in the mid-eighteenth century , Chinese papers were generally used in rooms of a more intimate nature than the Supper Room--bedchambers, dressing rooms, closets, and the like.53 Cornforth and Fowler add that State rooms were generally decorated in a more conservative fashion than other rooms.54 The use of a Chinese paper in the Supper Room would therefore have been extremely unlikely.

Based on these considerations, the curators' request that the Supper Room wallpaper be removed was granted. This paper was taken down by two professional conservators (John Bertalan and Betty Hollyday) and stabilized before being placed in storage at the Department of Collections.

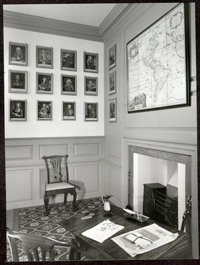

Removal of Chinese Wallpaper - Study

As in the case of the Supper Room, no documentation existed to suggest the use of a Chinese wallpaper in the Library. Palace documents in fact, seemed to mitigate against it. In 1769, Joseph Kidd recorded a charge of 0/15/0 for "Brass Nailing Pictures in the Study."55 The inventory of Governor Botetourt's possessions indicates that there were twenty such "prints" or pictures in the library.56 The use of so many pictures in so small a space would have been quite illogical with a scenic Chinese wallpaper. It appears moreover, that Governor Botetourt's library was housed in a built-in bookcase, which would have preempted still more wall space.57 The evidence indicated then, that the Chinese paper should come out. The curator's request to that effect was approved by the Program Planning and Review Committee.

Some question still remains in the writer's mind as to whether the pictures "brass-nailed" by Kidd were in frames (as currently shown) or whether they were applied directly to the walls in the manner of the English "Print Room" popularized by Lord Cardigan around 1760. At Erdig in Clwyd, Wales is such a room, decorated with Chinese prints. This space, a closet, occupies a position (relative to the bedchamber) much like that of the Palace Library. See the report on reconstruction of the Palace, for a full discussion of this possibility.

Overmantel - His Lordship's Bedchamber

Although "One Chimney looking Glass" was mentioned among the standing furniture in Governor Botetourt's chamber,58 the engraved looking glass built into the overmantel in the 1930s was added as an afterthought.59 (See Figs. 30 & 31.) Citing an example at Hampton Court as precedent,60 the architects built sections of a vertical "Queen Anne" style looking glass into the horizontal overmantel. There appears to be no precedent for the use of engraved glasses in this sort of application. Furthermore, the very listing of this chimney glass in the inventory implies that it was movable. On the basis of these facts, the Architects' Office complied with the curator's request that the overmantel in "his Lordship's Chamber" be returned to its original condition (i.e., having a flat panel rather than an engraved glass built onto the overmantel). In accordance with the inventory, a movable chimney glass of appropriate character was obtained by the curators and installed over the fireplace.

Overmantel Upper Middle Room

Consistent with the 1770 listing of Botetourt's possessions in the Middle Room, the curators acquired a carved and gilt Roccoco chimney glass for use over the fireplace.61 As in the case of "His Lordship's Bedchamber," the overmantel in the Middle Room had originally been completed with a flat panel over the fireplace, and later provided with a built-in looking glass instead.62 (See figs. 32 & 33.) Subsequently, this glass was also removed, and the void covered with a movable chimney glass. (See fig. 34.) When this glass was removed, it became clear that the Roccoco glass taking its place would not entirely cover the void. It was therefore decided, that the original condition of the overmantel with its flat panel and bolection moldings should be restored. This change was therefore made in accordance with original working drawing #116A. Following this change, installation of the present Roccoco chimney glass was completed. (See fig. 35.)

Hobgrates - Dining Room, Little Middle Room and Library

In the earlier decades of the eighteenth century, coal was rarely if ever used for domestic heating in Virginia. Writing in 1724, Hugh Jones remarked:

There is coal enough in the country, but good firewood being so plentiful that it encumbers the land, they have no necessity for the trouble and expence of digging up the bowels of the earth and conveying them afterwards to their several habitations.63

Five years later, William Byrd of Westover, wrote to London, instructing his correspondent:

Only the iron hearths and stoves with their appurtenances, sell for me, there being no coals burnt in this country.64

By the third quarter of the eighteenth century, coal burning stoves were being used by wealthy Virginians. The ballroom wing of the Governor's Palace, completed without fireplaces around 1755, may have been heated with coal stoves from the very beginning.65 In 1773, Robert Carter Nicholas ordered a "Bath Stove" from England for use in his house in Williamsburg, alluding to a similar device owned by Secretary, Thomas Nelson.66 By 1787, the use of coal had become common enough that Thomas Jefferson could write:

The country on James River ... is replete with mineral coal of a very excellent quality. Being in the hands of many proprietors, pits have been opened, and before [the Revolution] were worked to an extent equal to the demand.6736

Documentary evidence points strongly to the use of coal grates at the Palace during Botetourt's time. From Botetourt's records in England, it is clear that such grates were used at Stoke, the Governor's English country house.68 At the time of his death here in 1770, he owned 1000 bushels of sea coal.69 The Governor is also known to have purchased for use at the Palace 5 grates (presumably movable) from the estate of his predecessor, Francis Fauquier.70 Four of these were quite expensive, and seemingly appear in the 1770 inventory of Botetourt's furnishings in the Chamber over the front Parlour, the Chamber over the Dining Room, His Lordship's Bedchamber and the Middle Room.71 The inventory of standing furniture further mentions a grate in the Front Parlour.72 The failure of the inventory to mention either grates or andirons in the Hall, Pantry, Dining Room and Study suggests that built-in grates were employed in these rooms.

On the basis of this reasoning, the Department of Collections purchased three cast-iron hob-grates and requested their installation in three of the rooms mentioned above. (See figs. 36, 37, & 38). Because only 3 original pieces could be located, the Hall is presently allowed to remain without the built-in grate suggested by the inventory.

A curatorial research report on 18th century grates was made available to the Architects' Office for the study of grate installations.73 Guided by examples from this and other sources, details were developed for building out the cheeks of the fireplaces to receive grates in the Dining Room, Warming Room and Study. Photographs of a fireplace at Cedar Grove, Pennsylvania, and grates at Longnor Hall, in Norfolk, England, proved especially helpful.74 (See figs. 39, 40 & 40a).

Miscellaneous Alterations - Cellars

Upon request of the curatorial staff, architectural arrangements for the storage of "pipes" or barrels of spirits in the Palace cellars were altered somewhat. Previously, wine barrels in the "Passage" rested about 36" above the cellar floor on wooden timbers laid across eight low brick partitions. (See fig. 41). The curators maintained that such a storage arrangement would have been closer to the floor, pointing out the extreme difficulty involved in lifting a full container of wine onto a surface 36" high.

A check of our records indicated that the height and existence of brick partitions had been inferred from several columns of holes let into the original south foundation wall. (See fig. 42). Based on the conclusion that these holes had provided keys for adjoining brickwork, the architects had detailed a series of brick partitions in 1940, believing they supported an assembly for storing containers of wine.75

Upon recommendation of the Program Planning and Review Committee, the curators' request for removal of these brick partitions was approved. Drawings were prepared, detailing their replacement with a series of 5 x 5 wooden sleepers laid directly on the cellar floor. Although no conclusion could be reached concerning the original purpose of the holes mentioned above, it was decided to position the sleepers on center with them.

Throughout the cellars, large timber storage racks had been cut out to accommodate the curvature of the barrels. The curators requested that these timbers be cut down to eliminate these "cradles," reasoning that it would have been necessary on occasion to roll barrels along, the racks. A photograph of storage facilities in the undercroft of Drayton House seemed to confirm the absence of any cuts for the barrels on such racks. (See fig. 43).

38In the Binn Cellar, iron pins were driven into 20th century mortar joints above each bin to provide for delft plaques identifying the contents of each bin (arrack, madiera, etc.). Because the door of the Binn Cellar was to be kept locked for interpretive purposes, the existing visitor barrier was no longer necessary and was thus removed.

In the Cyder Cellar, the "Stenton Wine Cabinet" was fitted with locking hardware which fixes the door slightly ajar. This arrangement allows visitors a view of the cabinet's interior while preventing theft of the wine bottles. The exteriors of this cabinet and the closet nearby received a coat of simulated white-wash, as did all existing architectural woodwork throughout the cellars. The doors of both cabinet and closet were fitted with appropriate hardware.

More storage space was provided for the items inventoried in the Cook's Cellar by building shelves into the arched opening of the west chimney foundation. Similar shelving arrangements survive at the Rideout House in Annapolis, Maryland and at Drayton Hall near Charleston, SC.76 What appears to have been late shelving of a similar nature survived at the Wythe House until the late 1920s.77

To further assist in recreating the inventoried furnishings and equipage of the Palace cellars, drawings of an appropriate sawhorse design were prepared and sent to the Department of Collections for approval and fabrication by foundation craftsmen. These horses were designed along the lines of examples pictured in Diderot's Encyclopedia,78 and one example in particular illustrated in R. A. Salaman's Dictionary of Tools of the Woodworking and Applied Arts, p. 442. (See figs. 44-46).

In order to improve the quality of illumination in the cellars, various light fixtures were either moved or eliminated altogether. 39 Over the door of the Binn Cellar, a special fixture was installed to eliminate shadows cast by the shelf on which the previous fixture rested. The "Stenton Wine Cabinet" was fitted with a hidden lighting fixture to provide low level illumination for the closet interior.

Interior Paint Colors

Among the more evident changes made in refurnishing the Governor's Palace is the revision of its paint schemes. The original decorative schemes of the reconstructed Palace interior were largely the work of consulting interior architect Susan Higgison Nash of Boston. With material assembled by the restoration's research staff in hand, Mrs. Nash set about the formidable task of recreating the building's interior finishes, performing the tasks of designer, historian and technician. With respect to her methods, Mrs. Nash explained:

Just as the architects have attempted to place themselves in the position of the original builders and to act as proxies for them, I tried to adapt my experience with colors to the usages of Colonial times and to learn from documents and actual examples as much as may be gleaned from them.79

This idea of standing in "proxy" for the eighteenth century craftsman was meant quite literally. Mrs. Nash felt it was possible to discern the stylistic intentions of the Colonial designers. In one article she commented:

"The judgment and taste of Colonial painters are as apparent as [those] of the craftsmen builders. They achieved harmony and contrast and used their colors meaningly with a full comprehension of fitness."80

Such interpretation of the Colonial painters' judgment and taste was inevitably influenced by Mrs. Nash's own methods as a designer. Commenting on her work with the restoration, she wrote:

The background of the interior scene is made up of the wall treatments, hangings, window treatments and vistas from one room or hall to another ... The color 41 and texture of this background give meaning, life, and variety. Thus, the study of this color and texture must proceed execution, and be so considered as to include the scheme of foreground, and the scheme of sequence from room to room.81

Emphasis on sequence, vistas, and the relationship of wall colors to furnishings characterize Mrs. Nash's approach then. She appears to have been especially concerned with paint colors as a foil against which to view furnishings and costumes. On this particular matter, she further commented:

Interior painting forms most of the background. The furnishings form a part of this background and most of the foreground...Interior painting and furnishings should always be considered together as interrelated and both as related to the costume and dress habits of those persons who will use the rooms .82 (My emphasis)

Mrs. Nash's frequent use of warm, creamy yellow hues may have stemmed from her concern that the wall colors provide a suitable backdrop for the walnut and mahogany furnishings. In this regard, it's significant that she once mentioned choosing furniture on the basis of "form, scale and color ."83 (my emphasis.)

This is not to say that the schemes she developed had no basis in the documents. For instance, the leather hangings of the Upper Middle Room and the original paint colors of the Parlor and Dining Room took their cues from the historical evidence.84 No use, however, was made of the fabrics inventoried after Lord Botetourt's death in 1770, since the building was intended to portray the period around 1750.85

In some cases, the colors of rooms were matched to certain decorative features. The Ballroom paint, for example, was selected to accord with the background of the Chinese wallpaper chosen for 42 the Supper Room.86 In the Warming Room a deep mulberry color was mixed to match delft tiles in the fireplace surround.87

The recent decision to move the Palace into the Botetourt era has made it possible to use a wealth of color related information contained in the 1770 inventory and other contemporary documents. In those areas where no historical evidence was available, an effort was made to develop a rational, historical approach to color selection, founded on surviving examples of paint from other contexts or on historical circumstances.

Fortunately, documents specifically spelled out the early use of paint in the two major first floor rooms of the main house. On May 2, 1727, the Council issued an order that

... the great Dining room and Parlour thereto adjoining be new painted, the one of pearl colour the other of cream colour ...88

The colors now seen in these two rooms are believed to represent what the terms "pearl" and "cream" connoted in the eighteenth century, though a dearth of information made it necessary to use early nineteenth recipes in their formulation.

For the making of cream color, one author recommended that spruce yellow or yellow ochre be combined with white in the ratio of one to thirty pounds, adding that "the yellow tinge may be varied at pleasure."89

For the making of pearl color, the same author instructed that "one teaspoon of Prussian Blue; and one teaspoon of Spruce Yellow" be added to "one pint of white Lead."

Writing to a friend in 1750, Sir William Chambers noted that among other colors, "a pearl or what is called Paris grey ..." was to be considered a suitable colour for rooms.90 According to Cornforth and Fowler, this "Paris grey and French grey" became especially fashionable during the 1760s and 1770s, having 43 "pink and blue ... but no yellow." Such colors were apparently used at Osterley, Garrick's Villa in Hampton, and at Fawley in 1771.91 The documented use of blue moreen window curtains in the Dining Room and the Palace92 suggested that the "Pearl" color to be used in that room should tend more toward blue--having no yellow as mentioned by Cornforth and Fowler.

Because documentary evidence suggested that cream and pearl colors remained in use well into the eighteenth century,93 it was decided to use these colors in the Parlor and Dining Room as documented in 1727.

The Pantry, Little Middle Room, and Powder Room formed what was obviously a suite of service rooms. Because no documentation on the paint colors in these rooms survived, it was decided that their finishes should portray the use of an inexpensive iron-oxide pigment, suitable for utility areas.94

Botetourt records uncovered in England by Mr. Hood shed new light on the interior scheme of the Ballroom. Accounts for Botetourt's purchases in England clearly reflect the assembly of materials for the "plain blue paper" mentioned by Robert Beverly in his letter of 1771. In recreating this color, the curatorial staff was guided by the mention of Prussian Blue and Blue Verditer in the Botetourt accounts and by an actual fragment of plain blue wallpaper from Osterley Park in Middlesex, England.

The use of "dead white" paint on the woodwork along with this blue paper and its gilt border finds a parallel in these instructions written by Benjamin Franklin to his wife from England in 1767:

Paint the Wainscot a dead white; Paper the Walls blue, and tack the gilt Border around just above the Surbase and under the Cornish.9544

Undoubtedly, Franklin was intent on recreating some scheme he had recently seen in England. Zoffany's painting of Sir Lawrence Dundas and his grandson provides a good example of one such scheme. (See fig. 47).

In eighteenth century parlence, the term "dead white" connoted a flat, white color obtained by using a finish coat of white lead and turpentine over two primings of white lead in linseed oil. This technique became fashionable in the 1760s as evidenced by one New York advertisement offering to paint rooms dead white "...after the most accurate method now followed in London ...."96

This color owed its "whiteness" to the use of turpentine rather than linseed oil as the vehicle. It has been suggested that whites would always have been more yellow than the present "dead white" in the Ballroom. However, in a 1664 agreement for the painting of Clarendon House, we find the following stipulation:

All the white paint to be warranted yt it shall be so Truly done as yt shall not turne yellow under penalty of reimbursing one halfe of ye price which shall be paid for it.97

Oznabrigs and gilt leather borders mentioned in the inventory as being earmarked for use in the Supper Room made it clear that Botetourt intended to decorate this space in a fashion similar to the Ballroom, but never succeeded in doing so.98 The new decorative scheme thus represents the Supper Room as it might have appeared just after the Ballroom wing was completed early in 1750s. The stone color used here was quite popular in England and here in America, and is copied from the original color of George Mason's Chinese Room at Gunston Hall, completed in 1758.99

In 1770, Sir William Chambers wrote to a friend:

...with regard to the painting of your Parlours if they are for a common [public] use Stone Colour will last best and cheapest ....100 (My emphasis).45

To another correspondent, he wrote:

... If you have any particular fancy about painting your principal rooms , my intention is to finish the whole in a fine stone colour ....101 (my emphasis).

Here in America, cash books of the Philadelphia druggist Christopher Marshall indicated that he was selling "Stone Colour" in 1776.102

In the upstairs rooms, the contents of Governor Botetourt's inventory were extremely helpful in developing a rational scheme of paint colors. Green window curtains in the chamber over the Dining Room and a suite of 12 green bamboo chairs--divided between this room and the chamber over the Parlour suggested a predominately green color scheme, carried through the two east rooms.103 The "picking out" of moldings in white is based on contemporary parallels documented in the correspondence of Sir William Chambers and Thomas Chippendale--two of England's leading practitioners. In 1771, Chambers wrote to one Robert Gregory, advising that Gregory's parlors be painted " ... pea green with white mouldings ...."104

At Nostell Priory, Thomas Chippendale specified that "the Cornice...be painted white and green, and the moulding of ye upper part of the Cove ...." be treated likewise in the "Anty room Next to ye green damask bed Chamber."105 That the chamber and antechamber mentioned in Chippendale's letter were to be decorated with green as the predominant color, further suggested that the two eastern chambers at the Palace could have been treated en suite as well.

The actual scheme of moldings to be picked out in white is based on the original paint scheme of the Saloon at Clandon Park in Surrey.106 Articulation of the pilaster flutes and filets was suggested by details from State Bedroom at Blickling Hall and from 46 the Boudois at Attingham Park.107 The recently restored 17th century gilding schemes at Ham House seem to reiterate the methods used at Clandon for picking out mouldings.

In the chamber over the Parlor, carved moldings picked out in a darker green are based on a 1759 reference to the drawing room of Lady Carolyn Fox, where carvings were picked out in two shades of green and varnished.108 The naturalistic painting of the carved grapes flanking the overmantel parallels examples here in America and in England. At the Nichols House in Providence, Rhode Island, scrapings revealed that the carved cherubim flanking two cupboard doors had been polychromed naturalistically. This scheme is believed to date from the period around 1760.109 In Fredericksburg, Virginia, another instance of naturalistic polychroming was found when paint investigations uncovered evidence of brightly painted carving of fruit--adorning an overmantel at "The Chimneys"--built in 1771.110 (See figs. 41, 47 & 48). Evidence of similar practices in England is to be found in the lavish painting of a carved bed at Alnwick Castle, in Northumberland, executed about 1780.111

In his Lordship's Bedchamber, the use of a yellow was suggested by mention of "8 Yellow bottom chairs" in the inventory. Although some of these chairs were also used in the Study, it was decided to use a blue color in this room--since a "blue venetian blind" was inventoried among its contents.112

Plaster surfaces throughout the building were covered with a simulated Whitewash--brushed on in such a way as to recreate the random strokes of similar work from the eighteenth century.

In general the new paint colors are lighter, reflecting a tendency toward a lighter palette in the 1770s. They are somewhat less yellow than previously, taking into account the recent findings of paint specialists such as Morgan Phillips, Frank S. Welsh, and 47 others. These findings indicate that the linseed oil vehicle of eighteenth century paints yellows and darkens considerably in the absence of daylight. Thus, colors uncovered by scraping often appear much yellower and darker than when they were first applied.113 Soon after deliberations on the Palace paints began, it became clear that there would not be sufficient time or resources to conduct a comprehensive field survey of surviving 18th century paint schemes. Decisions were therefore based more on documented precedent than on actual examinations of samples in the field. The present colors at the Palace are therefore regarded as an interim solution to the question of how Governor Botetourt decorated his interiors.

Recent research has pointed up the need to review paint schemes not only at the Palace but all over the Historic Area. As more and more interiors are restored with paint schemes based on scientific analysis, our own colors and analytical techniques will probably be called into question. We have already had several inquiries along this line, prompted by new paint schemes at the William Paca House in Annapolis and, more recently, at Mount Vernon here in Virginia.114 Similar changes are in the works at Monticello as well. In view of this trend, a comprehensive study of our own historic paints, undertaken by a qualified professional consultant should be a priority.

Visitor Barriers

Owing to changes in furnishings and interpretive strategy, it was necessary to design new visitor barriers for the Parlor, Pantry, Dining Room, Little Middle Room, Study and the Governor's Bedchamber. As construction proceeded it was necessary to revise three barriers:

- 1.Dining Room - As initially designed, this barrier was found to extend into the room to a point where it interfered with placement of the carpet. On the other hand, it was necessary to maintain enough space within the barrier to accommodate all persons in a single tour. The resulting compromise lengthened the barrier while reducing its projection into the room. In order to obtain still more room inside the barrier, the hinges of the passage door were revised so as to allow it to open back flat against the paneling. Plexiglas shields were added to this barrier to protect the furnishings within visitors' reach.

- 2.Parlor - As in the case of the Dining Room, it was deemed necessary to have more room inside the barrier. This barrier was also lengthened and the door hinges modified so as to allow the hall door to open back flat against the paneling.

- 3.Study - As originally designed, this barrier stopped visitors at the door of the study. Because the bookcase was situated on the north wall of the room, it was felt that visitors would have difficulty seeing the bookcase. Accordingly, a new barrier was designed which formed a well inside the room, allowing visitors to see the books.

As in the Dining Room, Plexiglas shields were added to the barrier in the Governor's Bedchamber to protect nearby furnishings.

Cleaning and Refinishing of Floors

Available evidence concerning 18th century housekeeping practice indicates that wooden floors were generally left unwaxed. In order to achieve as authentic an appearance as possible, all wooden floors were stripped, and only those areas subjected to visitor traffic were re-waxed. The floor in the Upper Middle Room posed a special problem. An oak table which stood in the center of the room since the 1930s had created great differences in the amount of wear sustained by the center of the floor versus its perimeter.

Initially, this floor was stripped and a pigmented wax applied in an attempt to even out the difference in color. The color produced by this treatment was far too dark, however, and the floor was stripped and waxed two more times before a satisfactory finish was obtained.

In the Entrance Hall, the grout between the stone pavers was scrubbed so as to remove substantial accumulations of dirt which had developed over the years.

Cleaning and Refinishing of Paneling

Prior to installation of the arms, walnut paneling below the cornice in the Hall, Passage and Stairwell was cleaned with mineral spirits and given a coat of tung oil varnish in those areas where the finish was gone. Prior to applications of this finish, a light stain was used to blend back in those areas which had been discolored by wear.

Footnotes

Thomas Waterman suggested however that the plan was a working drawing made for a remodelling of the building. See The Mansions of Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1945), p. 32-3.

In either case, it is quite obvious that the plan was made somewhat more hastily than the drawing of Barboursville.

The piece photographed by Moorehead is illustrated and discussed in Gusler's Furniture of Eastern Virginia..., pp. 21-3. It is currently owned by Colonial Williamsburg (acc. no. 1978-13). For the Moorehead photo of this piece, see S. P. Moorehead photo album entitled, "Photographs of Interiors," f. 2.

The Accounts of Thomas Chippendale mention blinds "fixed in Mahogany Boxes." See Gilbert, The Life and Works of Thomas Chippendale , I, p. 233.

Catherine Lynn documents Chinese papers in New York (1773) and Virginia (1768) though her interpretation of the evidence is open to question. It seems that no indisputable example of Chinese paper can be documented in America during the 1750s--the period during which the Supper Room was completed. See Catherine Lynn Wallpaper in America (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1980), pp. 99-106.

It is also possible that these rooms were heated with charcoal-burning braziers, or perhaps not heated at all.

For the gilt leather borders, see note 32.

FIGURES

FIG. 1. Arms arrangements--Chevening House, Kent, England.

FIG. 1. Arms arrangements--Chevening House, Kent, England.

FIG. 2. Watercolor of Harris' arms arrangements--Queen's Guard Chamber--Windsor Castle.

FIG. 2. Watercolor of Harris' arms arrangements--Queen's Guard Chamber--Windsor Castle.

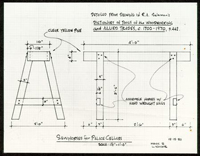

FIG. 3. Sketch of center hanger for flagstaffs--Hall.

FIG. 3. Sketch of center hanger for flagstaffs--Hall.

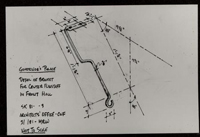

FIG. 4. Sketch of baseplate for gilt medallion--Hall ceiling.

FIG. 4. Sketch of baseplate for gilt medallion--Hall ceiling.

FIG. 5. New silver cabinet--Pantry. [No digital image]

FIG. 5a. Pantry Shelving--new and existing installations.

FIG. 5a. Pantry Shelving--new and existing installations.

FIG. 7. "Jib" doors--Library at Chicheley Hall, Buckinghamshire, England. [No digital image]

FIG. 8. Jefferson Plan of Palace--note interior dimensions of Parlor Closet.

FIG. 8. Jefferson Plan of Palace--note interior dimensions of Parlor Closet.

FIG. 9. Jefferson Plan of Barboursville--note indication of buffets.

FIG. 9. Jefferson Plan of Barboursville--note indication of buffets.

FIG. 10. "The Tea-Table"--Walpole Collection of Political Prints--note buffet to the left.

FIG. 10. "The Tea-Table"--Walpole Collection of Political Prints--note buffet to the left.

FIG. 12. Buffet--Benjamin Waller House.

FIG. 12. Buffet--Benjamin Waller House.

FIG. 13. Buffet--James Geddy House.

FIG. 13. Buffet--James Geddy House.

FIG. 14. Buffet--Governor's Palace.

FIG. 14. Buffet--Governor's Palace.

FIG. 15. Sketch of Buffet--Governor's Palace.

FIG. 15. Sketch of Buffet--Governor's Palace.

FIG. 16. Buffet--Frampton Court, Gloucestershire, England.

FIG. 16. Buffet--Frampton Court, Gloucestershire, England.

FIG. 17. Buffet--Ormley Lodge in Ham, Surrey, England.

FIG. 17. Buffet--Ormley Lodge in Ham, Surrey, England.

FIG. 18. Freestanding buffet--King's Weston, Gloucestershire, England.

FIG. 18. Freestanding buffet--King's Weston, Gloucestershire, England.

FIG. 19. "Tartuff's Banquet," William Hogarth--note lower, skirted section of buffet.

FIG. 19. "Tartuff's Banquet," William Hogarth--note lower, skirted section of buffet.

FIG. 20. Buffet--Cedar Grove, Pa.--note opening cut into planar surround.

FIG. 20. Buffet--Cedar Grove, Pa.--note opening cut into planar surround.

FIG. 21. Virginia high chest base--note configuration of skirt.

FIG. 21. Virginia high chest base--note configuration of skirt.

FIG. 21a. Powder Room shelving prior to removal.

FIG. 21a. Powder Room shelving prior to removal.

FIG. 21b. Cornice in Ballroom before revision.

FIG. 21b. Cornice in Ballroom before revision.

FIG. 22. Sketch of ceiling bosses--Ballroom wing.

FIG. 22. Sketch of ceiling bosses--Ballroom wing.

FIG. 23. Drawing of door escutcheon by Robert Adam.

FIG. 23. Drawing of door escutcheon by Robert Adam.

FIG. 24. "Back of the State House, Philadelphia"--note stovepipes protruding from windows.

FIG. 24. "Back of the State House, Philadelphia"--note stovepipes protruding from windows.

FIG. 25. Sketch of exterior stovepipe hardware. [No digital image]

FIG. 26. "Chinese Room" at Gunston Hall as it existed-early in this century.

FIG. 26. "Chinese Room" at Gunston Hall as it existed-early in this century.

FIG. 27. Doorway at Honington Hall, Warwickshire, England. R. T. H. Halsey attempted to tie Buckland to the creation of this woodwork. [No digital image]

FIG. 28. Powell room in the Metropolitan Museum as shown in Halsey's The Homes of Our Ancestors. Note Chinese wallpaper.

FIG. 28. Powell room in the Metropolitan Museum as shown in Halsey's The Homes of Our Ancestors. Note Chinese wallpaper.

FIG. 29. Gadsby's Tavern "Alcove" as shown in Halsey's The Homes of our Ancestors. Note Chinese wallpaper.

FIG. 29. Gadsby's Tavern "Alcove" as shown in Halsey's The Homes of our Ancestors. Note Chinese wallpaper.

FIG. 30. His Lordship's Bedchamber--note panel above fireplace. [No digital image]

FIG. 31. His Lordship's Bedchamber--note substitution of chimney glass above fireplace.

FIG. 31. His Lordship's Bedchamber--note substitution of chimney glass above fireplace.

FIG. 32. Upper Middle Room--note panel above fireplace.

FIG. 32. Upper Middle Room--note panel above fireplace.

FIG. 33. Upper Middle Room--note substitution of looking glass over fireplace.

FIG. 33. Upper Middle Room--note substitution of looking glass over fireplace.

FIG. 34. Movable glass formerly in place in Upper Middle Room.

FIG. 34. Movable glass formerly in place in Upper Middle Room.

FIG. 35. Roccoco glass now in position--Upper Middle Room.

FIG. 35. Roccoco glass now in position--Upper Middle Room.

FIG. 36. Hob-grate now installed in Dining Room.

FIG. 36. Hob-grate now installed in Dining Room.

FIG. 37. Hob-grate now installed in Little Middle Room.

FIG. 37. Hob-grate now installed in Little Middle Room.

FIG. 38. Hob-grate now installed in Study.

FIG. 38. Hob-grate now installed in Study.

FIG. 39. Fireplace--Cedar Grove, Pa.--cheeks built inward, probably for grate.

FIG. 39. Fireplace--Cedar Grove, Pa.--cheeks built inward, probably for grate.

FIG. 40a. Fireplace--Longnor Hall.

FIG. 40a. Fireplace--Longnor Hall.

FIG. 40. Fireplace--Longor Hall, Norfolk, England-cheeks built inward to accommodate grate.

FIG. 40. Fireplace--Longor Hall, Norfolk, England-cheeks built inward to accommodate grate.

FIG. 42. Original holes in south foundation as revealed by archaeology.

FIG. 42. Original holes in south foundation as revealed by archaeology.

FIG. 43. Undercroft--Drayton House, Northamptonshire, England--note racks and disposition of barrels.

FIG. 43. Undercroft--Drayton House, Northamptonshire, England--note racks and disposition of barrels.

FIG. 44. Sawhorse illustrated in Salaman's Dictionary of Tools ....

FIG. 44. Sawhorse illustrated in Salaman's Dictionary of Tools ....

FIG. 45. Sawhorse illustrated in Diderot's L'Encyclopedie....

FIG. 45. Sawhorse illustrated in Diderot's L'Encyclopedie....

ADDENDUM

According to Mark R. Wenger, the following numbered photographs were never taken or inserted in this volume although spaces were left for them in the original manuscript:

Figures 5, 7, 25, 27, 30, 40a, and 41