Archaeological Testing at Rich Neck

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0360

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2009

Archaeological Testing at Rich Neck

Prepared for:

McCale Development Corporation

Submitted by:

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Department of Archaeological Research

P.O. Box 1776

Williamsburg, VA 23187-1776

(757) 220-7330

March 1993

Re-issued

May 2001

| Page | |

| Management Summary | iii |

| List of Figures | ii |

| Chapter 1. Introduction and Background | 1 |

| Physical Description | 3 |

| Historical Overview of Middle Plantation | 3 |

| Historical Overview of Rich Neck | 7 |

| Prehistoric Overview | 11 |

| Environmental Setting | 14 |

| Previous Archaeology | 15 |

| Chapter 2. Research Design and Results | 18 |

| Method for Testing the Yorkshire Terrace | 18 |

| Results | 20 |

| Feature 1 ‒ Brick Foundation | 21 |

| Feature 2 ‒ Possible Cellar | 24 |

| Feature 3 ‒ Clay Anomaly | 25 |

| Feature 4 ‒ Posthole Complex | 25 |

| Chapter 3. Interpretations | 26 |

| Recommendations for Further Work | 32 |

| Bibliography | 34 |

| Appendix 1. Artifact Inventory | 37 |

| Page | |

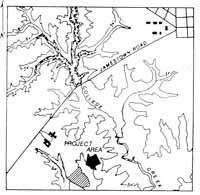

| Figure 1. Project area | 2 |

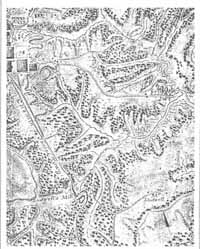

| Figure 2. Desandrouins Map of 1781 | 6 |

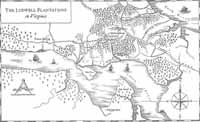

| Figure 3. The Ludwell plantation in Virginia | 9 |

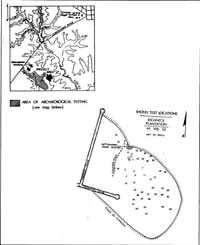

| Figure 4. Plan of Phase I shovel tests | 16 |

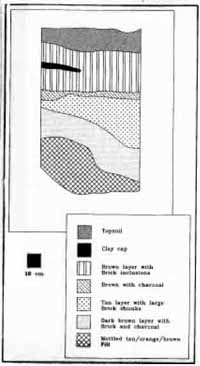

| Figure 5. Typical stratigraphic sequence | 21 |

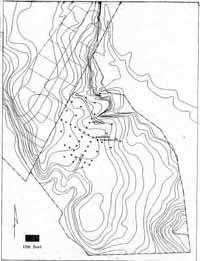

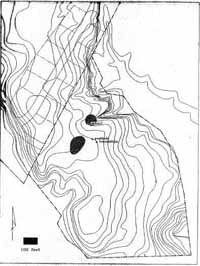

| Figure 6. Plan of test units | 22 |

| Figure 7. Brick foundation | 23 |

| Figure 8. Projected length of foundation | 23 |

| Figure 9. Profile of possible cellar | 24 |

| Figure 10. Clay anomaly | 25 |

| Figure 11. Plan of posthole complex | 26 |

| Figure 12. Concentrations of architectural material | 28 |

| Figure 13. Concentration of kitchen related material | 29 |

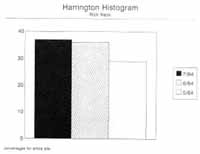

| Figure 14. English pipestem diameters | 30 |

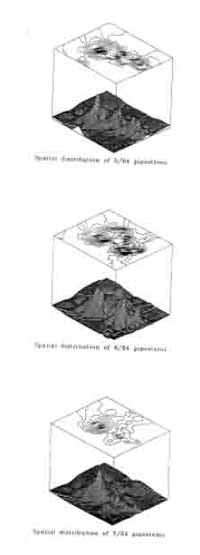

| Figure 15. Pipestem distribution based on bore diameters | 31 |

Management Summary

A four week archaeological assessment of Site 44WB52, which lies within the Yorkshire portion of the proposed Holly Hills development, was conducted by Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Archaeological Research in November and December of 1992. This assessment was designed to identify site boundaries, and characterize site integrity and structure. The field procedures consisted of hand excavation of a series of .75 meter-square test units, and documentation of all stratigraphy and features. The results of this effort are described below.

Evaluation of Site 44WB52 indicates that it is a multi-component site with three separate and distinct occupations. A small scatter of prehistoric artifacts was recovered, including one non-diagnostic projectile point. A light spread of eighteenth century artifacts, probably associated with a nearby slave quarter was also identified. The major occupation was a large scale Middle Plantation farmstead occupied during the second half of the seventeenth century. A total of 47 test units was excavated, exposing a varied and sometimes complex stratigraphic sequence.

Four features were identified including three possible seventeenth-century structures. The two and a half brick wide foundation identified in a test unit was probably the plantation's main dwelling. Artifacts found near the foundation suggest a second half of the seventeenth-century occupation. A single large posthole was uncovered just west of the brick foundation. This may represent the remains of a post structure. Artifacts recovered from around this feature also suggested a second half of the century occupation. Two features were uncovered northwest of the brick foundation. A test unit revealed a complex stratigraphic sequence of fill layers similar to those found within filled cellars. A clay feature located nearby may either be the results of twentieth-century logging, or may be another seventeenth-century activity area.

In summary, the evaluation of 44WB52 succeeded in documenting the boundaries and integrity of this early colonial plantation. In order to refine the exact placement of activity areas, a more intensive testing program is required. Once this is accomplished, areas in need of further examination can be prioritized based on development plans and archaeological significance.

Chapter 1.

Introduction and Background

At the request of the McCale Development Corporation, in cooperation with John E. Matthews and Associates Inc., an archaeological appraisal (Phase II testing) of the Yorkshire Terrace portion of the pending Holly Hills housing development was initiated by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Archaeological Research. Previous archaeology had identified a number of sites on and near this parcel. One of these earlier investigations, the initial assessment of the Yorkshire portion of the Holly Hills tract, conducted by the Tidewater Cultural Resource Center, uncovered a large site (44WB52) associated with the early colonial community known as Middle Plantation. The presence of this site necessitated a thorough evaluation of this area.

Documentary research indicates that this tract was part of Rich Neck plantation, owned from the 17th through the 18th centuries by the Ludwell family of Greensprings. The 1781 Desandrouins Map indicates this area belonged to "M. Ludwell" and shows six buildings associated with this plantation. The map shows a road leading from the present-day Jamestown Road to the main group of structures, located on a ridge overlooking College Creek. A lone structure is shown east of the main body of the plantation. To the northeast, across Jamestown Road, was Ludwell's Mill, also owned by the Ludwell family.

The project afforded an opportunity to explore aspects of the physical organization of Middle Plantation, the seventeenth-century settlement that preceded Williamsburg. Previous efforts by the Department of Archaeological Research to locate components of this scattered community have met with only mixed results. This project provided for an unqualified appraisal of one of the many individual plantations that grew up within the settlement's boundaries. The Rich Neck property is clearly one of the most important of these early plantations associated with Middle Plantation, and its study can reveal much about this component of the community.

The excavation began on November 23, 1992 and took four weeks to complete. The project was carried out under the general supervision of Marley R. Brown III, the director of the Department of Archaeological Research at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Staff Archaeologist David Muraca directed the field work and prepared this report. Field Technician Steve Atkins supervised a field crew made up of Ywone Edwards, Beth Anderson, Audrey Horning, and Marie Blake. Laboratory processing was performed by Laboratory Technician Pegeen McLaughlin under the direction of Amy Kowalski, Laboratory Analyst. This report was illustrated by Kimberly Wagner.

2Physical Description

The project area is located in Williamsburg, Virginia. The tract to be tested encompasses approximately 30 acres of land located off Jamestown Road. Bounded by the housing development of Yorkshire of Williamsburg and Walsingham Academy to the north and west respectively, and by branches of College Creek to the east and south, the tract consists of a large broad terrace surrounded by ravines on three sides. The ravines drain into College Creek, that in turn flows into the James River. No small streams or springs are presently found within the project area. The terrace would have been located near the western boundary of the ill defined community known as Middle Plantation. Access to College Creek provided one transportation route to the rest of Middle Plantation, as well as to Jamestown.

Historical Overview of Middle Plantation

The settlement known as Middle Plantation grew out of the Virginia colony's desire to establish a marked boundary between the tobacco plantations scattered along the lower James River, and their intermittently hostile Indian neighbors. Using land and tax incentives as inducements to attract settlers and a Palisade to demarcate the colonial boundary, colony administrators sought to establish a buffer zone between the Powhatans and the lower peninsula settlements. Middle Plantation took on a linear appearance that mimicked the palisade. Early settlers obtained large tracts of land that gave the community a scattered, patchwork appearance.

The first mention of Middle Plantation (which probably received its name because of its location between the York River and the James River) in official records was in "An Act for the Seating of the Middle Plantation."1 The act, issued by the Council and House of Burgesses on February 1, 1632/33 ordered:

That every fortyeth Man be chosen and maynteyned out of the tithable Persons of all the Inhabitants, within the Compasse of the Forrest conteyned between Queenes Creeke in Charles River and Archers Hope Creeke in James River, with all the Lands included, to the Bay of Chesepiake, and it is appoynted that sayd Men be there at the Plantation of Doct. John Pott, newlie built before the first day of March next, and that the Men be imployed in building of Houses, securing that tract of Land lying between the sayd creeks. An to do such other Workes as soone as may bee, as may defray the Chardges of that Worke, and to be directed therein as they shall be ordered by the Governor and Cousell. And yf any free Men shall this Yeare before the first day of May, voluntarilie go and seat upon sayd place of the Middle Plantation, they shall have fifty acres of Land Inheritance, and be free from all Taxes and publique Chardges according to a former Act of Assembly made the forth Day of September last past (Hening 1927).

Designed to provide a buffer between the plantations located on the lower peninsula and the Indians situated to the northwest, the settlement was organized around the Palisade of 1634, a wooden barrier that ran between the James River and York River. The palisade is mentioned as a boundary marker for fifteen of the seventeenth-century land patents that make up this settlement (Edwards 1990). Archaeological evidence of the palisade has been recently unearthed at Bruton Heights, just north of the palace lands above the CSX railroad tracks, at College Landing, and near Williamsburg's gallows (Muraca and Hellier 1992; Hunter, Brown and Samford 1984; Outlaw, Tyrer, and Thomas 1991).

Middle Plantation remained a dispersed settlement throughout most of the seventeenth century. At first, the area was in the hands of a few individuals such as George Menifie, Secretary Kemp, John Utey, Humphrey Higgenson, Charles Leech, and Richard Popeley, all of whom owned large tracts of land. By the 4 second half of the century, the size of the patents issued became smaller with numerous 50, 100, and 200 acre tracts being acquired by new settlers (Edwards 1990).

In 1676, Middle Plantation was described as "the very heart and center of the country" but had yet to achieve any cultural or political importance (Muraca and Hellier 1992). This changed later that year when the community served as a staging ground for Nathaniel Bacon's assault on Jamestown. During the attack, the capital was destroyed and its state house burned at the hands of Nathaniel Bacon's men. The assembly was forced to convene away from Jamestown in 1677 and chose Middle Plantation as a convenient meeting place. This may have been a precedent for moving the government to Williamsburg in 1699. Later in 1677, the King's soldiers were sent to pursue Bacon at Middle Plantation (Muraca and Hellier 1992).

During the last quarter of the seventeenth century, Middle Plantation began the transformation from rural settlement to urban center. In 1674 Bruton Parish was formed by uniting Marston and Middletown Parishes. Four years later donations were being collected to build a new church to be located at Middle Plantation. The new church, proposed to be built of brick, would replace the two (wooden?) churches that had served the formerly separate parishes. Land for the church along with a cash contribution was donated by John Page, a prominent Middle Plantation resident with major landholdings.

In 1679, the vestry contracted with George Marable to construct the church for £350 Sterling. This contract was lost and construction delayed until 1681 when Francis Page built the church for £150 Sterling and 90 lbs. of tobacco. The church was completed in 1683 and dedicated in 1684. Problems with shoddy construction techniques would plague the building until its replacement was built in 1716. The original brick church, 29 feet by 66 feet in size, was supported by buttresses spaced 9 to 10 feet apart on the northern and southern sides.

Soon after the church was completed, England's King William ordered a college to be built in the colony. Named the College of William and Mary, the school was located at Middle Plantation in 1693. An end of the century description of Middle Plantation suggests it had evolved into the precursor of an urban community.

Here are great helps and advances made already towards the beginning of a Town, a Church, and ordinary, several stores, two Mills, a smiths shop a Grammar School and above all the Colledge (Anonymous 1699).

The state house at Jamestown was rebuilt in the 1670s, only to burn again in 1698. The arrival of Francis Nicholson, newly appointed Governor of the Colony in 1699 and the lack of a state house in Jamestown led to the establishment of the town of Williamsburg, on the site of Middle Plantation (Edwards 1990).

5Historical Overview of Rich Neck Plantation

The Rich Neck parcel appears to be a portion of 1200 acres granted in 1635 to George Minifie (or Menifie) Esqr., described as "a neck of land comonly [sic] called the Rich Neck, bounded on w. with a br. of Archers Hope Cr…." (Nugent 1979:24) .2 The precise boundaries of the Rich Neck lands are unclear, but appear to have extended to the north of Route 5 (Brown and Hunter 1987:81). 6 Menifie, in addition to being a lawyer and a merchant of the Corporation of James City, also served as an agent for the Virginia landholders who were residing in England (Meyer and Dorman 1987:448). After Menifie's death in 1644, the land passed to Richard Kempe, who lived there and was later buried on the property (Goodwin 1971).

Sometime after his 1650 arrival in the colonies and before his death between 1653 and 1656, Sir Thomas Lunsford married the widow of Richard Kempe, who had previously owned the Rich Neck parcel. With Elizabeth Kempe, Thomas Lunsford had one daughter, Catherine (Merz 1976). At some unspecified time in the mid-seventeenth century, the Rich Neck property passed from Lunsford to Thomas Ludwell. Ludwell was appointed Secretary of the State of Virginia in 1660, a duty that entailed making reports concerning the condition of Virginia affairs to the English secretary of state. Ludwell died in October 1678 and was buried on the Rich Neck estate (Anonymous 1911:209).

The property passed to Ludwell's brother Philip, who appeared to have begun living at Rich Neck in 1675 while his brother was in England. By 1680 he was described as Philip Ludwell of Rich Neck. It was Philip who acquired Greenspring Plantation, perhaps the most famous of the Ludwell properties, when he married the widow of the late Governor William Berkeley of Greenspring (Carson 1954).

In 1674, a portion of Rich Neck (a 330 acre tract) was sold to Thomas Ballard. Nineteen years later, the same tract was sold again, this time to the trustees of the College of William and Mary. The college was built on this tract, and still owns 30 of the original 330 acres (Anonymous 1901:91).

Rich Neck plantation passed to Philip's son and then grandson. The latter, Philip Ludwell III, was born in 1716 (Ludwell 1913). At his death in 1767 Philip Ludwell III owned numerous large estates that were listed in his inventory, including those at Hot Water, Green Spring, and Rich Neck on the north side of the James River. His Scotland estate was located on the south side of the river, in Surry County. He left the Rich Neck property to his youngest daughter Frances. At Frances' premature death, another daughter, Lucy Ludwell Paradise received the Rich Neck land. A 1767 inventory of Philip Ludwell's estate lists 21 slaves and numerous livestock (cattle, sheep, hogs, and horses) at the Rich Neck plantation, as well as over 1600 pounds of tobacco and agricultural tools. The Mill Quarter, presumably that associated with the Rich Neck Plantation and Ludwell's Mill, contained eight additional slaves (Ludwell 1913).

The Rich Neck tract that Lucy Ludwell Paradise and her husband owned consisted of 3459 acres in 1796 (Anonymous 1914). Lucy and John Paradise lived in London, with the property being managed by Cary Wilkinson (Palmer 1883). Around 1807, Lucy Paradise sold two tracts of Rich Neck land, (a 600 acre parcel and a 200 acre parcel) with the remainder of the property remaining within the Ludwell-Paradise family for some twenty-four years following Lucy Paradise's death in 1814. In 1838, the remaining acres of the former Rich Neck Plantation were sold, including the mill on what is now Lake Matoaka. The mill

7

Figure 3. The Ludwell plantation in Virginia.

portion of the property was purchased by William Jones. Numerous other transactions for various parts of this property were conducted during the remainder of the 19th century. The area is shown on the Gilmer Map of 1863 as Jones Mill (destroyed).

Figure 3. The Ludwell plantation in Virginia.

portion of the property was purchased by William Jones. Numerous other transactions for various parts of this property were conducted during the remainder of the 19th century. The area is shown on the Gilmer Map of 1863 as Jones Mill (destroyed).

In 1846, Robert F. Cole purchased 602½ acres of Rich Neck land, most likely the larger tract sold by Lucy Paradise in 1807. Cole purchased this property from the estate of William Edloe for the sum of $3,050. Descendants of Robert Cole retained control of this land into the twentieth century (Cole Family Papers nd).

A Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission archaeological site report form was prepared on Ludwell's Mill in 1971 (VHLC 1971). A local resident, Willard Gilley, indicated that a mill was working there into the 1920s, and that it was burned around 1945. Since the Gilmer Map suggests that it was destroyed by 1863, this later oral history seems to indicate that the mill was rebuilt after the Civil War. The mill itself, for which all evidence was most likely destroyed by Route 5, was a 35' × 50' frame structure. The old road passing south of the mill was apparent on both sides of Route 5 in 1971.

Two major property-owners, now own a large portion of the property that encompasses the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Rich Neck Plantation. The remainder has recently been subdivided by Yorkshire of Williamsburg.

Prehistoric occupations at Rich Neck seem to be limited to the Archaic and Woodland periods. The flat terraces near College Creek would have provided an ideal environment for fall and winter campsites. Shellfish were an important and accessible resource during the winter and early spring. The presence of a shell midden (44JC146) on the yet to be surveyed portion of this tract indicates that the 8 area was used during the Woodland period. Archaeological survey of the rest of the Holly Hills tract should uncover other small campsites and shell middens. The small prehistoric component found during this testing project reinforces this possibility.

Prehistoric Overview

Like the rest of eastern Virginia, the area around Williamsburg has been occupied for several thousand years.3 Native Americans, who first occupied the Eastern seaboard no later than 12,000 years ago, hunted on, and later cultivated the land long before the arrival of the first European settlers. For convenience, archaeologists and ethnohistorians have sub-divided this long history into rough chronological periods that mirror changes in adaptive strategies. These periods—the Paleo-Indian (9200-8000 B.C.), Archaic (8000-1200 B.C.) and Woodland (1200 B.C.-1560 A.D.)—have been used for several decades. Recent researchers, including Gardner (1980) and Custer (1984), have provided a more refined, behaviorally-based classification system that will be used here as a basis for discussion, although the earlier scheme may be used for convenience and compatibility with other research in the site description and analysis sections.

The earliest phase of Native American occupation on the James-York peninsula includes periods traditionally referred to as the Paleo-Indian (9200-8000 B.C.) and the Early Archaic (8000-6800 B.C.) (Gardner 1989). Most archaeologists regard cultural evolution during this period as a direct adaptation to changes in post-Pleistocene environments. Though a variety of food resources were locally available, hunting provided the main basis for subsistence. The transition from a colder Pleistocene environment in the latter part of this phase probably reduced the numbers of several large herbivores, such as mammoths and mastodons, forcing greater reliance on elk and deer as the main food sources. Social groups most likely organized themselves at the band level, an alliance of several family groups that remained flexible enough to adapt to the changes in land and resource availability brought on by seasonal cycles and long-term environmental changes.

These earliest hunters selected high-quality materials from which to produce their tools, that were primarily double-sided implements called bifaces. Finely-crafted fluted points of non-local crypotocrystallines (especially jasper and chert) remain the sole diagnostic artifacts for the Paleo-Indian period. In most cases the discovery of a single fluted point is sufficient to prove Paleo-Indian occupation. Because these points are quite rare, and because of the limited number of surviving tools, the sites are difficult to find. The preference during the early part of this first phase for high-quality, non-local lithic materials may have limited a group's 9 range of subsistence and, depending on availability, may have increased the competition for scarce lithic resources.

The most compelling model of settlement for the early hunters in Virginia revolves around jasper outcrops in the western part of the state. No one has yet reported the discovery of an undisturbed early hunter site on the lower James-York peninsula. The few discoveries within other parts of Virginia's Coastal Plain do suggest possible higher population densities than local data reveals. Despite the limited nature of this data, Robert Hunter has proposed a preliminary site model for the Tidewater. Early hunters, he has suggested, would have located on "Late Pleistocene-Early Holocene landforms that provided a water source and game attracting capability. Anticipated site types for the area would include small, short-duration campsites and possibly kill and butchering sites" (Hunter 1986). However, the scarcity of research on the nature of paleo-environments makes site prediction difficult at best.

The second chronological period of the new scheme (6500-2000 B.C.) falls entirely within the period commonly referred to as the Archaic. Significant environmental changes occurred over this long time period. Warm, moist, and increasingly seasonable climates, along with the spread of an oak-hemlock forest produced an even greater diversity in both plant and animal communities. This in turn allowed a corresponding shift in the settlement pattern, technology, and subsistence pattern of Native American groups. It was probably during the last part of this long phase, after 3000 B.C., that the estuarine environment stabilized.

Important changes in tool production and use occurred during this phase. The production of tools from locally-available lithic materials, a trend that had begun late in the first phase, supplanted earlier reliance on non-local cryptocrystalline materials. In response to changes in the variety of food resources, Native Americans developed an increasingly specialized tool kit, including ground stone tools such as axes, grinding stones, and other plant-processing tools.

According to Gardner (1980) and Custer (1984), several types of sites characterize this period. Permanent sites, whose locations were linked to the availability of food resources and thus to the carrying capacity of the ecosystem, include both large and small base camps. Hunting and gathering forays were conducted from transient or procurement sites in an effort to exploit specific resources.

The third phase in the new scheme includes periods traditionally known as the Late Archaic/Transitional (2000-1200 B.C.), the Early Woodland (1200-500 B.C.), and the Middle Woodland (500 B.C.-1000 A.D.). This grouping, according to Robert Hunter (1986), emphasizes cultural continuity, and also affords a more pragmatic solution to the multi-component and non-discrete nature of sites in this area. A large quantity of archaeological and environmental data has allowed archaeologists to study this phase in greater detail than the others. Though much of the environmental data has been extrapolated from elsewhere, several important environmental changes including a stabilized sea level, an increase in the salinization 10 of coastal rivers, and an increase in the numbers of anadromous fishes and shellfish, particularly oysters. This appears to have initiated the shift to a more sedentary economy, one based increasingly on estuarine and riverine resources. Groups established and maintained larger camps for longer periods, and in response to these changing conditions developed new technologies for the acquisition, storage, and preparation of food. Despite this more sedentary lifestyle, however, seasonal forays into the interior zones for game, particularly deer and turkey, and other foodstuffs would have continued.

The number and variety of diagnostic artifacts increase on sites of this phase, Bowls made of steatite, a non-local soap stone, appear early in the phase, but are quickly replaced by a ceramic technology whose range of variability in form, tempering agents, and surface treatments and decorations provides archaeologists with another possible means of classifying cultural change and determining exchange systems. The settlement pattern proposed by Gardner (1980) and Custer (1984) is similar to that for the previous period. Groups established base camps on "elevated landforms adjacent to a highly productive, riverine or estuarine setting." Procurement sites were likely situated "along interior watercourses in areas varying from small rises along streams to high hilltops" (Hunter 1986).

The final phase, corresponding roughly to the period previously identified as Late Woodland, extends from 1000 A.D. to 1560 A.D., the latter date being considered as the beginning of contact with Europeans. During this phase, settlements became increasingly permanent. European accounts of Indian lifeways during the period of early contact describe groups as settling more intensively within Inner Coastal areas. The greater diversity of natural resources farther upstream would have supported broader-based consumption. It seems clear also that groups were becoming more reliant on agricultural products like beans, maize, and squash. Thus, a desire to locate near agriculturally-productive areas probably would have influenced site location.

Significant changes in the manufacture of ceramics occur during this phase. The use of shell as a tempering agent becomes predominant, and various types of exterior decoration appear more commonly. Style and form in both ceramics and lithics seem to have become increasingly localized. This has made it possible for archaeologists to better identify and understand the movements and distributions of various groups, though it is by no means well understood. One thing seems clear, however—within the Mid-Atlantic region, the network of exchange and interaction grew in size and intricacy during this period.

Environmental Setting

The site of Rich Neck Plantation is contained within the city of Williamsburg, approximately 2400 feet east of Jamestown Road and northwest of Route 199. It is located on a flat terrace 70 feet in elevation, and is surrounded by deep ravines through which run tributaries of College Creek to the east and west.

11The portion of the terrace examined by this project is covered with small deciduous hardwoods, including oaks and sweet gums, as well as some pine and holly. Ground cover, which is sparse in most areas, consists of ferns, golden ragwort, and Virginia bluebells. A few areas are overgrown with honeysuckle and briars. The entire area has been logged extensively, as evidenced by the large number of logging roads, machine cuts, and piles of brush still visible throughout the area. Archaeological testing revealed that the majority of the area was once under cultivation.

Previous Archaeological Study

The most recent archaeological survey of a portion of the Holly Hills tract was prompted by discoveries made during the construction of Yorkshire Drive in 1988. With the permission of the Geddy family, who owned the property at that time, a terrace adjacent to the new road was examined at that time. Parallel transects were established, spaced about fifty feet apart. Shovel test pits were excavated at forty foot intervals along the transects in search of below surface remains. A crew of thirteen graduate students from William and Mary's Departments of Anthropology and History and other volunteers conducted the survey under the direction of Patricia Samford and Gregory Brown for the Tidewater Cultural Resource Center of the College of William and Mary.

The location of buildings associated with Rich Neck plantation (Site 44WB52) was suggested by brick concentrations. Shovel tests were put in at ten to thirty foot intervals radially from the brick concentration in all directions. The 1988 testing suggested there may have been two residential areas, one dating to the mid or late seventeenth century, and the other dating to the early to mid eighteenth century.

During survey of the then Geddy property, two other sites were recorded. One was the location of a late nineteenth-century tenant farm house (44WB53), and the other was an earthen dam (44WB54).

In addition to the 1988 survey, an earlier, less formal survey was completed by the Virginia Research Center for Archaeology. This preliminary reconnaissance of the property in 1981 identified two sites adjacent to College Creek. Shovel testing identified an early colonial site (44JC145) and a small prehistoric occupation (44JC146). The shovel tests uncovered seventeenth-century artifacts, including fragments of Bellarmine, local pipe stems, case bottle, and Merida coarseware. This coarseware has been identified on other sites that date from 1640-1670. The prehistoric site consisted of a scatter of crushed shell. No diagnostic artifacts were found in the shell scatter, making the dating of this occupation impossible at this time.

Nearby excavations have uncovered a slave quarter, associated with the late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century plantation at Rich Neck. In 1990 the Department 12 of Archaeological Research conducted a salvage excavation of three features located in the Yorkshire development located directly adjacent to Holly Hills. Excavation revealed three root cellars one of which was brick lined. Evidence from other sites suggests that slave quarters would have been located over these features (Kelso 1984). These dwellings would have probably been situated on wooden sills leaving no trace in the ground.

Chapter 2.

Research Design and Results

The importance of an archaeological resource is derived from the nature of information it can provide about the past. Archaeological sites known to be located on the Holly Hills tract derive their significance from several themes identified in Colonial Williamsburg's plan for future archaeological research. The Department of Archaeological Research has a long-standing interest in Middle Plantation, the community that preceded Williamsburg. Accurate identification and further study of the seventeenth-century site located on this tract would provide important information about the physical layout of the Middle Plantation settlement, and about the economic basis of the community. Recent projects that have broadened awareness about Middle Plantation include excavations at Bruton Parish and Bruton Heights. The Department of Archaeological Research is now compiling all existing archaeological information about Middle Plantation. This work is in anticipation of a series of excavations over the next seven years to prepare for a major exhibit on the transition from Middle Plantation to Williamsburg to be mounted in honor of the City's Tercentary celebration in 1999.

The primary research goal of this project was the identification of the Rich Neck plantation in the ground, including site boundaries, architectural features, activity areas and to characterize the relative degree of preservation. A systematic approach using regularly spaced test units was used to insure a representative sample was collected from the site. In all, less than one quarter of one percent of the site was excavated. While this represented only a small fraction of the material currently located on the site, it was sufficient in size to address basic questions about the site's physical character without compromising its integrity.

Methods for Testing the Yorkshire Terrace

The testing strategy for this project included the use of regularly spaced, systematically placed test units. This approach was designed to insure the identification of activity areas, and was designed to understand the spatial boundaries of the site. In addition an analysis of the artifacts was undertaken in order to determine the date of occupation, as well as site function.

A grid system was established to gain spatial control of the site. Test units were placed at ten and twenty meter intervals to accurately observe both horizontal and vertical aspects of the site. The unit size selected, 0.75 by 0.75 meters (2.5 feet), allowed for retrieval of a representative artifact sample, accurate recording of stratigraphy, and the assessment of sub-surface features with only minimal disturbance to the site. An interval of 10-20 meters (40 to 80 feet) between units 14 was deemed sufficient to assess the distribution of artifacts and to identify any activity areas within the site.

The coordinate system that established the location of test units was initiated from a single datum point, permanently marked by an iron reinforcing rod. Coordinates and context numbers were assigned to each unit accordingly. Measurements were made using the metric system, in keeping with the standard recording procedures of the Department of Archaeological Research. A map showing terrain, modern disturbances, and unit locations were produced for the site. Black and white photographs, along with color slides taken of select features, were used to document the testing results.

Test units were excavated by stratigraphic layers using both shovels and hand trowels. All soil was sifted through ¼ inch mesh and all artifacts were collected regardless of their age. Restricted ground visibility prevented the collection of artifacts located on the ground surface. Physical descriptions of both layers and features were recorded using the Department's standard form. Features were drawn in plan before being covered in plastic and back-filled. Excavation of features was restricted to poorly understood examples in hopes of identifying the function of these features. Profile drawings of the soil stratigraphy were completed before the holes were back-filled.

The finds were washed and inventoried using a standard descriptive typology for both historic and prehistoric materials. No minimum vessel counts were attempted, due to the limited nature of the project. Faunal remains were identified as to species when possible. Artifacts in need of stabilization were sent to Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Conservation. All materials, along with the documentation, are stored at the Department of Archaeological Research.

Results

A total of 47 test units was excavated on the terrace that contains 44WB52. Excavation revealed a variety of stratigraphic sequences, ranging from simple to complex. A number of different types of features were uncovered as well. This section will describe the physical attributes of the layers and features found, and try to establish the functions of the latter.

Occupations from three different time periods were identified on the site. A small scatter of prehistoric artifacts, including eight flakes and a broken projectile point, was unearthed. The point was fractured and could not be identified. No prehistoric pottery was found, indicating the flakes and point may date to the pre-Woodland period. Also found was a light scatter of eighteenth-century artifacts. These finds were probably related to activities associated with the slave quarters located nearby in the Yorkshire of Williamsburg development. The main component of the site is the second half of the seventeenth-century occupation. All further discussion will pertain solely to this early colonial occupation.

15The most stratigraphically simple test squares contained only two cultural layers. Topsoil, a dark brown sandy loam, was found universally, and ranged in thickness from 2 to 6 centimeters. This layer was characterized by a light scatter of artifacts. Under the topsoil was a brown sandy loam that varied in thickness from 8 to 15 centimeters. This loam was formed by plowing, which folds several layers into one. Artifact densities for this layer varied, depending on location, with most finds being small in size, the result of years of plowing.

Most of the units on the terrace contained an additional layer underneath the modern plowzone. This layer ranged in color from light brown to tannish orange, and varied in thickness from a few centimeters to over a ½ meter deep. Artifacts were unevenly distributed throughout this layer.

Seven units revealed the presence of more than the three layers mentioned above. The additional layers were created either in a natural manner, such as erosion, or by cultural means, such as a cellar. Some of these additional layers contained large amounts of man-made materials, others little or none. Analysis of the artifact distributions in these additional layers will be reported on in the next section of this text.

The testing of site 44WB52 revealed a large number of features. Only the features formed by cultural activity will be described in detail.

Figure 5. Typical stratigraphic sequence.

Figure 5. Typical stratigraphic sequence.

Feature 1 ‒ Brick Foundation and Builder's Trench

A test excavation at 550N/530E contained a portion of a substantial brick foundation. Ten orange/red handmade bricks were exposed. The foundation ran roughly east-west, and extended out of the unit for two meters to the east and one meter to the west. Probing suggested the wall was 2.5 bricks wide. The bricks were in laid in course, with some evidence of shell tempered mortar surviving between bricks. All the bricks were placed using the same arrangement, that of headers, 17 only laid on their narrow side. Probing revealed the presence of a second course of bricks underneath the exposed course.

The foundation was sealed by the plow zone and was contained in a builder's trench. This trench extended from 10 to 16 centimeters north of the foundation. The soil of the builder's trench was a dark loam with some brick and mortar fragments present. The builder's trench was not excavated.

Artifacts found in the layers above the foundation include pan roofing tiles, mortar, and plaster. Domestic artifacts included a stone marble, tobacco pipes, earthenware fragments, and an animal bone. These finds suggest that the building was once a dwelling. A wooden structure was likely seated on the brick foundation, with plastered walls, and a roof of earthenware tiles. It is not possible to definitively date when the dwelling stood by the excavation of a single test unit; however, the artifacts recovered suggest a second half of the seventeenth-century occupation. The site-wide absence of white salt-glazed stoneware, first manufactured in 1715, suggests the building was abandoned by the beginning of the eighteenth-century. The dwelling was situated between Jamestown Road and College Creek, each of which would have provided access to Jamestown.

Feature 2 ‒ Possible Cellar

The test unit located at 570N/510E revealed a complex stratigraphic sequence. Under a 10 centimeters thick plowzone were several layers that sloped to the north. Most of these layers appeared to be deposited on purpose. Only the bottom layer had the appearance of being washed in by rain. Several layers were

Figure 7. Brick foundation.

18

Figure 7. Brick foundation.

18

Figure 8. Projected length of foundation.

Figure 8. Projected length of foundation.

Figure 9. Profile of possible cellar.

19

identified, and they ranged in thickness from 10 to 40 cm. The uppermost layers (Contexts 50, 52, and 73) were brown loams with heavy concentrations of brick and charcoal. These layers contained a variety of artifacts including ceramics, table glass, animal bones, tobacco pipes, a gun flint, and wine bottle glass. The bottom layer (Context 54) was a mixed tan and orange silt, with a few brick bats and animal bones, but otherwise devoid of artifacts.

Figure 9. Profile of possible cellar.

19

identified, and they ranged in thickness from 10 to 40 cm. The uppermost layers (Contexts 50, 52, and 73) were brown loams with heavy concentrations of brick and charcoal. These layers contained a variety of artifacts including ceramics, table glass, animal bones, tobacco pipes, a gun flint, and wine bottle glass. The bottom layer (Context 54) was a mixed tan and orange silt, with a few brick bats and animal bones, but otherwise devoid of artifacts.

Preliminary evidence suggests this feature may have once been a cellar. Another possible interpretation is that of a clay quarrying pit either for brick making or daub making. Quarry pits have been found on several other sites including those associated with Middle Plantation. The domestic nature of the artifacts found in these fill layers counters any speculation about a specialized activity area located on this part of the site. Artifacts, including coarsewares, pipe bowls, and case bottle fragments suggest the feature was filled during the second half of the seventeenth century.

Feature 3 ‒ Clay Anomaly

Excavation of the unit located 10 meters north of the possible cellar revealed a deep, complicated stratigraphic sequence. Under the plowed soil was a brown layer with heavy charcoal flecking and numerous artifacts. This thick layer (25 centimeters) sealed an orange clay feature and a darker brown layer. Expansion of this excavation unit to 2.25 by .75 meters exposed a large, irregular orange clay feature, that contained large quantities of brick bats. Coring revealed the second dark brown sandy layer that was just over 10 centimeters thick. This layer was not excavated.

20An area heavily disturbed by logging activities was located just to the east of the clay feature. It is possible that this unusual stratigraphic sequence is related to this modern agricultural activity. This explanation does not reconcile the large number of early colonial artifacts found near the clay feature. It is also possible that this area was a colonial activity area that has been damaged by loggers.

Feature 4 ‒ Posthole Complex

A large posthole was uncovered in the unit located just west of the brick foundation. The posthole's size and fill were similar to remains usually found with earthfast structures. The feature extended out of the 75 by 75 centimeter unit in all four directions. The post hole was filled with a redeposited dark orange sandy clay, usually found only in holes that permeate subsoil to a significant depth.

In the eastern corner of the posthole was an irregularly shaped area of grey sandy loam, with brick and charcoal flecking. Areas like this usually signify post repair, a common phenomenon for earthfast buildings. The presence of a circular post mold located within this area supported the conclusion of structural repair.

This feature complex was not excavated and therefore cannot be dated. Artifacts found in the plowed soils above the features were the same seventeenth-century finds located over the entire site. Both clinker and coal were noted in the plowzone that indicated this area may have been used for industrial purposes.

Chapter 3.

Interpretations

The archaeological exploration of the Yorkshire terrace portion of Holly Hills identified a large seventeenth-century occupation, a smaller scatter of eighteenth century artifacts, and a small prehistoric component. While most of the site was contained within the terrace, artifacts were recovered near the Yorkshire of Williamsburg development boundary. Conversations with Yorkshire landowners revealed that artifacts were routinely found in the yards of houses bordering Holly Hills. Evidence of three possible structures associated with an unusually large scatter of artifacts (100 × 100 meters) was uncovered. Almost all of the artifacts recovered date to the second half of the seventeenth century. Within this scatter were two separate hot spots for both architectural and kitchen related artifacts.

Artifacts suggested the site was occupied sometime after 1650 and survived for approximately fifty years. The presence of Fulham stoneware, first manufactured in 1684 suggested the site existed until near the end of the seventeenth century. The absence of several later artifact types, including a popular stoneware that was introduced around 1715, indicated this complex was abandoned around to the beginning of the eighteenth century. Three different maker's identification marks were found on imported tobacco pipe fragments. The marks consisted of:

- JF—attributed to James Fox—used during the second half of the seventeenth century

- LE—attributed to Llewellin Evans—used from 1661-1686

- MB—maker unknown—found on sites occupied from 1650-1680

The integrity of the site is good. Plowing and logging has destroyed most of the cultural layers associated with the site; however, the features have survived undamaged. Most archaeological sites in Virginia have suffered from plowing. Usually the cultural layers are destroyed completely when sites are plowed. It is unclear whether all of the layers associated with the seventeenth-century site at Rich Neck were destroyed. A layer underneath the modern plow zone has survived in some areas of the site. The presence of a few eighteenth century artifacts in this third layer suggests that this layer was also created by plowing.

Heavy concentrations of domestic and architectural artifacts indicate that a large-scale plantation once existed on this terrace. The architectural details suggest an af-fluence uncommon during the second half of the seven-teenth century in Tidewater Virginia. Roofing tiles, window glass, brick foundations, flooring tiles all suggest an unusually well made house for the period. The domestic artifacts offered a somewhat different picture. The relative scarcity and commonplace nature

22

Figure 12. Concentrations of architectural material.

of the domestic finds were surprising in view of the substance of the architectural remains, but the sample was an extremely small one.

Figure 12. Concentrations of architectural material.

of the domestic finds were surprising in view of the substance of the architectural remains, but the sample was an extremely small one.

While the majority of re-covered artifacts were either dom-estic or arch-itectural, a smat-tering of industrial related artifacts was also found. Several earthenware tiles, spotted with dripped lead glaze, were found on the site. These were interpreted as pottery kiln furniture, and suggested that ceramics were fired on site. Traveling potters were common early in the seventeenth century, but seen

23

Figure 13. Concentration of kitchen related material.

infrequently in the latter half of the century. Coal and clinker (burned coal) was also found on the site. No particular industrial activity can currently be associated with these finds.

Figure 13. Concentration of kitchen related material.

infrequently in the latter half of the century. Coal and clinker (burned coal) was also found on the site. No particular industrial activity can currently be associated with these finds.

Artifact density analysis indicates two major areas of activity on the site. The northernmost concentration is made up of predominantly architectural artifacts (nails, window glass, tiles). This large area (50 x 50 meters) contains the possible cellar feature and is northwest of the other structures identified by the testing. The southern concentration of artifacts consisted of predominantly food preparation, storage, and serving vessels. While some architectural material were also found in 24 this concentration, no buildings have yet been associated with this concentration. All of the buildings identified to date were located north of the southern area. Further investigations will probably reveal building(s) in this area.

Dating seventeenth-century artifacts is a difficult proposition. Unlike the eighteenth-century, which witnessed a well documented and technologically innovative ceramic industry, the seventeenth century experienced little technological alteration and even less documentation. While less important for the interpretation of short-lived or structurally simple sites, this lack of change complicates interpretation of complex sites like Rich Neck. Because there was little technological transition, later activities often mask earlier ones.

One artifact type that does undergo a change in the seventeenth century was the English tobacco pipe. In the 1950s, J.C. Harrington noted that imported pipestem bores decreased in diameter over time. He examined several archaeological assembleges and was able to establish the date ranges that correspond with specific pipestem diameters. Using Harrington's technique to organize the pipestems found on this site, the spatial distribution of each group of similar pipestems was plotted. By organizing the stems by diameter, a relative chronology can also be established.

Three groups of pipestem bore diameters were found on the site—5/64, 6/64, and 7/64. The earliest (7/64") was concentrated in two clusters. The largest cluster was centered around the possible cellar. A smaller group was located 40 meters to the south of the possible cellar, indicating at least one additional activity area existed during the first years of occupation of this site.

Figure 14. English pipestem diameters.

Figure 14. English pipestem diameters.

Figure 15. Pipestem distribution based on bore diameters.

Figure 15. Pipestem distribution based on bore diameters.

Pipestem bore diameters that measured 6/64" were also clustered around the possible cellar. A moderate concentration was also located 40 meters south of the possible cellar. Several smaller concentrations were noted along the eastern boundary of the site, including one just east of the brick foundation.

The majority of pipestems with bore diameters that measured 5/64 were also found just north of the possible cellar. Two additional peaks were also identified. One of these smaller concentrations was noted around the brick foundation and the structural post hole. An additional concentration was found approximately 25 and 35 meters due south of the brick foundation. No features have been identified in this area to date.

These results suggested some shift in the use of space on the site over time. The area around the possible cellar was used for the entire duration the site was occupied. The brick foundation along with the structural posthole seemed to date to the latter parts of the occupation. The presence of several clusters of pipestems near no known feature indicated that some major features associated with this massive site have yet to be uncovered.

Analysis of the artifacts suggested the plantation was probably established during the time period when Thomas Ludwell, controlled this property. It is possible that some of this complex predates Ludwell, and was constructed by Thomas Lundsford an earlier owner of the property. In 1678 Thomas Ludwell died, and the plantation passed to his brother, Philip. Known as Ludwell of Rich Neck, Philip managed the plantation until his death, when the plantation passed to his son. Artifacts dating to the time of Philip's stewardship predominated on this site. The site was apparently abandoned sometime after Philip's death, probably during the tenure of his son.

Recommendations for Further Work

The site is an important component of Middle Plantation, the community that preceded Williamsburg. Excavation of it will contribute to the understanding of the transition from rural to urban, and from frontier to capital. Its excavation is meaningful in terms of the internal structure of the site, as well as in terms of its relationship with other Middle Plantation sites.

The current project has successfully delineated the boundaries, activity areas, and integrity of this important site. While useful in defining the general nature of the site, this approach leaves unresolved the dilemma faced by the property's developers. Plans call for the establishment of a road and several lots within the project area. To ascertain which portions of the road, and which lots will contain significant archaeological remains a more refined archaeological assessment is necessary. Using intervals of 10 to 20 meters between test units, the current testing has identified several large (up to 50 × 50 meters), irregular shaped activity areas. In order to further define these activity areas, the spacing between units must be 27 reduced from 10 to 20 meters to intervals of 5 meters between excavation units. By collapsing the spacing between test units, the archaeological potential of the road and of particular lots can be determined.

Once activity areas within the site are well defined, they can be prioritized based on archaeological significance and the degree of impact from pending construction activities. The most important, threatened components of the site can then be explored. This type of project is well suited for the field school run by the Department of Archaeological Research each summer. This work could be completed by fall of this year.

The projected cost associated with collapsing the intervals between test units is $16,323 and will take six weeks to complete. This amount represents the actual cost of labor for the project. The Department of Archaeological Research will again absorb the costs of analysis and report production. Once the additional analysis of site structure is completed, a plan for site excavation can be generated in coordination with development plans and possible funding sources can be identified.

Bibliography

- 1699

- Speeches of Students of the College of William and Mary, Delivered May 1, 1699. William and Mary Quarterly X(2nd ser.): 323-337.

- 1914

- Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Volume 22 no. 3, page 271.

- 1901

- William and Mary Quarterly. Volume 10 no.1.

- 1911

- Ludwell Family. William and Mary Quarterly. Volume 19, No. 3 (1st series).

- 1987

- Phase II Evaluation Study of the Archaeological Resources Within the Proposed Route 199 Extension Corridor Alternate A Revised and A-2. Report submitted to the Virginia Department of Transportation by the Office of Archaeological Excavation, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1954

- Green Spring Plantation in the 17th Century. Unpublished report on file at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library.

- nd

- Special Collection, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.

- 1781

- Plan du terrein a' la Rive Gauche de la Riviere de James vis' a vis Jamestown en Virginia. Copy on file at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library.

- 1992

- Archaeological Investigation of the Northwest Corner of Bruton Parish's First Brick Church. Unpublished report on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1990

- "…Where the old Pales Stood:" Seventeenth-Century Settlement at Middle Plantation, Virginia. Unpublished manuscript on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 29

- 1987

- Archaeology at Port Anne. A Report on Site CL7, An Early 17th Century Colonial Site. Unpublished report on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1953

- Letter to M. L. Towery, date 9-2-53. In Letter File, Research Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1971

- Letter to Dorothy B. J. Ross date 2-23-71. In Letter File, Research Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1927

- Statues at Large. William & Mary Quarterly, Vol.I, ser 3.

- 1977

- Heritage and Historic Sites: An Inventory and Description of Historic Sites in James City County. 1977. Copy on file at the Department of Archaeological Research.

- 1984

- Kingsmill Plantations, 1619-1800: Archaeology of Country Life in Colonial Virginia. Academic Press, Orlando.

- 1913

- Appraisement of the Estate of Philip Ludwell, Esqr. Decd. (From the Ludwell Papers, Virginia Historical Society). Virginia Historical Magazine Volume 21 (395-416).

- 1976

- Letter to Carolyn L. Mears, dated 2-18-76. In Letter File, Research Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1987

- Adventurers of Purse and Person, Virginia, 1607-1624. Richmond: The Dietz Press, Inc.

- 1992

- Phase II Excavation of the Locust Grove Tract. Unpublished manuscript on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1992

- Archaeological Testing at Bruton Heights. Unpublished manuscript on file at the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1979

- Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants 1623-1666 Volume I. Originally published in 1634. Reprinted in 1979 by Virginia Book Company, Berryville, VA. 30

- 1991

- Archaeological Investigations of Mechanicsville to Kingsmill Virginia Natural Gas Pipeline. Prepared for Virginia Natural Gas, Norfolk, Virginia by Espey Huston and Associates, Inc., Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1883

- Calendar of Virginia State Papers. Volume 3, Richmond, p.67.

- 1781

- 39e Camp a Williamsburg le 26 Septembre…[Amerique Campagne, 1781.] Plan des differents campes occupes par l'Armee aux ordres de Mr. Le Comte De Rochambeau. Copy on file at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library.

- 1988

- Archaeological Survey of Rich Neck Plantation. Manuscript on file at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1971

- Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Archaeology Office. Archaeological Site Report File Number 137-52 on Ludwell's Mill. On file at the Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission, Richmond, Virginia.

Appendix 1.

Artifact Inventory

32

| AA | 1 | STONEWARE, WESTERWALD, FRAGMENT |

| AB | 25 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AC | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE, * |

| AD | 2 | CHARCOAL, CHARCOAL |

| AE | 1 | MARL, MARL |

| AF | 21 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AG | 4 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AH | 1 | IRON, UNID HARDWARE, ROLLED/SHEET |

| AA | 1 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AB | 17 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AC | 7 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AA | 2 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, PAINTED UNDER, BLUE |

| AC | 1 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, MISSING GLAZE |

| AD | 1 | DETACHED GLAZE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AE | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE |

| AF | 18 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AG | 2 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, LOCAL |

| AH | 1 | STONEWARE, WESTERWALD, FRAGMENT |

| AI | 1 | BONE, FAUNAL SPECIMEF, BURNED |

| AJ | 3 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE, * |

| AK | 1 | GREY CHERT, DEBITAGE, FLAKE FRAG/SHAT, NON-CORTICAL, WATER-WORN |

| AL | 29 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AM | 1 | IRON, NAIL, 2 TO 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AN | 3 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AA | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AB | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE |

| AC | 1 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT, WITH LEAD GLAZE, USED AS KILN FURNITURE |

| AD | 28 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AE | 5 | BOG IRON, FRAGMENT |

| AF | 2 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AA | 1 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AB | 1 | REFINED EARTHEN, CREAMWARE, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED, * |

| 33 | ||

| AC | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINDOW GLASS |

| AD | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, CASE BOTTLE |

| AE | 4 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE |

| AF | 1 | GLASS, COLORED, FRAGMENT, CONTAINER, GREEN |

| AG | 43 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AH | 1 | BONE, FAUNAL SPECIMEN, BURNED |

| AI | 1 | MARL, MARL |

| AJ | 2 | BOG IRON, FRAGMENT |

| AK | 43 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AL | 1 | TIN ALLOY, SPOON, HANDLE, TIN ALLOY (PEWTER) SPOON HANDLE. CONSERVED; RETURNED 3/29/96. |

| AM | 11 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AN | 1 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AA | 2 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AB | 2 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AC | 1 | MARL, MARL |

| AD | 2 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AA | 3 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AB | 5 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE, * |

| AC | 3 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AD | 1 | SHELL, SHELL |

| AE | 3 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AF | 5 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AA | 5 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AB | 1 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, MISSING GLAZE |

| AC | 1 | DETACHED GLAZE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AD | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, 17TH CENTURY, POSSIBLY FRENCH |

| AF | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, LOCAL |

| AG | 1 | STONEWARE, ENGLISH SW, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, STAFFORDSHIRE, LATE 17TH CENTURY |

| AH | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, STEM, MAKER'S MARK, *5/64'IF',JAMES FOX, SECOND HALF OF 17TH |

| AI | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, STEM, 7/64 |

| AJ | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, DOMESTIC, STEM |

| AK | 2 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, BOWL |

| AL | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE |

| AM | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINDOW GLASS |

| AN | 1 | BONE, FAUNAL SPECIMEN |

| AO | 5 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT |

| AP | 9 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AQ | 1 | STONE, STONE, UNWORKED |

| AR | 5 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AS | 1 | IRON, NAIL, 2 TO 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AT | 9 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AA | 3 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AB | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, LOCAL |

| AC | 21 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AD | 2 | STONEWARE, FULHAM SW, FRAGMENT, * |

| AE | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, DOMESTIC, BOWL |

| AF | 3 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE |

| AG | 1 | GLASS, CLRLESS LEAD, FRAGMENT, TABLE GLASS |

| AH | 1 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT |

| AI | 1 | BONE, FAUNAL SPECIMEN, BURNED |

| AJ | 2 | BONE, FAUNAL SPECIMEN |

| AK | 35 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AL | 1 | BOG IRON, FRAGMENT |

| AM | 2 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AN | 4 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AA | 6 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AB | 3 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, MISSING GLAZE |

| AC | 2 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, LOCAL |

| AD | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE |

| AE | 36 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AF | 1 | STONEWARE, FRECHEN BROWN, FRAGMENT |

| AG | 3 | STONEWARE, FULHAM SW, FRAGMENT, * |

| AH | 1 | STONEWARE, WESTERWALD, FRAGMENT |

| AI | 1 | STONEWARE, WESTERWALD, FRAGMENT, SPRIG MOLDED |

| AJ | 3 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, STEM, ALL 6/64 |

| AK | 7 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, BOWL |

| AL | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINDOW GLASS |

| AM | 1 | GLASS, CLRLESS LEAD, FRAGMENT, TABLE GLASS |

| AN | 4 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, CASE BOTTLE |

| AO | 13 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE |

| AP | 1 | MARL, MARL |

| AQ | 3 | BONE, FAUNAL SPECIMEN |

| AR | 1 | PLASTER, PLASTER, SHELL |

| AS | 7 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT |

| AT | 1 | LEAD, CASTING WASTE |

| AU | 2 | GREY CHERT, GUNFLINT, WORKED |

| AV | 1 | BLONDE/CARAMEL-, GUNFLINT, WORKED |

| AW | 83 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AX | 5 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AY | 4 | IRON, NAIL, 2 TO 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AZ | 4 | IRON, NAIL, OVER 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| BA | 11 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| BB | 2 | IRON, UNID HARDWARE |

| BC | 1 | BOG IRON, FRAGMENT |

| BD | 1 | IRON, UNID HARDWARE, ROLLED/SHEET |

| AA | 1 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, PAINTED UNDER, BLUE |

| AB | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, LOCAL |

| AC | 32 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AD | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, BURNED, LOCAL |

| AE | 2 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, BOWL |

| AF | 4 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, STEM, ONE IS 6/64, THREE ARE IMMEASURABLE |

| AG | 2 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, DOMESTIC, STEM |

| AH | 1 | GLASS, CLRLESS LEAD, FRAGMENT, TABLE GLASS, * |

| AI | 3 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, CASE BOTTLE |

| AJ | 1 | MARL, MARL |

| AK | 3 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE |

| AL | 1 | BONE, FAUNAL SPECIMEN, BURNED |

| AM | 5 | BONE, FAUNAL SPECIMEN |

| AN | 1 | OTHER ORGANIC, ORGANIC SUBST |

| AO | 9 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT |

| AP | 13 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT, PAVING TILE, WITH LEAD GLAZE, USED AS KILN FURNITURE |

| AQ | 10 | IRON, NAIL, 2 TO 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AR | 2 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AS | 8 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AT | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, BURNED |

| AU | 55 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AA | 1 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AB | 2 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AA | 1 | REFINED EARTHEN, CREAMWARE, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED, * |

| AB | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, RED-BOD SLIP, FRAGMENT |

| AC | 27 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AD | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, STEM, 6/64 |

| AE | 1 | GLASS, CLRLESS LEAD, FRAGMENT, TABLE GLASS |

| AF | 1 | MARL, MARL |

| AG | 1 | BOG IRON, FRAGMENT |

| AH | 38 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AI | 1 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AJ | 1 | IRON, NAIL, 2 TO 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AK | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, LOCAL |

| AA | 5 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AB | 2 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, PAINTED UNDER, PURPLE |

| AC | 1 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, MISSING GLAZE |

| 36 | ||

| AD | 1 | DETACHED GLAZE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AE | 43 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AF | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, LOCAL |

| AG | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, BURNED |

| AH | 1 | STONEWARE, FULHAM SW, FRAGMENT, * |

| AI | 1 | STONEWARE, WESTERWALD, FRAGMENT |

| AJ | 3 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, STEM, TWO ARE 6/64, ONE IS IMMEASURABLE |

| AK | 4 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, BOWL, ONE HAS PARTIAL STEM: 5/64 |

| AL | 2 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, ROULETTED, BOWL |

| AM | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, DOMESTIC, STEM |

| AN | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINDOW GLASS |

| AO | 4 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE |

| AP | 2 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, CASE BOTTLE |

| AQ | 2 | MARL, MARL |

| AR | 4 | SHELL, SHELL |

| AS | 1 | BONE, FAUNAL SPECIMEN |

| AT | 2 | BLONDE/CARAMEL-, DEBITAGE, FLAKE FRAG/SHAT, 1-74% CORTEX |

| AU | 3 | IRON, NAIL, 2 TO 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AV | 2 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AW | 3 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AX | 4 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT |

| AY | 1 | BOG IRON, FRAGMENT |

| AZ | 128 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AA | 1 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AB | 1 | DETACHED GLAZE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AC | 1 | REFINED EARTHEN, CREAMWARE, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED, * |

| AD | 1 | GLASS, CLRLESS LEAD, FRAGMENT, TABLE GLASS |

| AE | 2 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE |

| AF | 1 | GREY CHERT, DEBITAGE, FLAKE FRAG/SHAT, NON-CORTICAL |

| AG | 4 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AH | 3 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT |

| AI | 2 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, LOCAL |

| AJ | 62 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AK | 1 | BOG IRON, FRAGMENT |

| AL | 2 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AM | 1 | IRON, UNID HARDWARE |

| AA | 1 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AA | 8 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| 37 | ||

| AB | 3 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, MISSING GLAZE |

| AC | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, N MIDLAND SLIP, FRAGMENT |

| AD | 2 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, LOCAL |

| AE | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AF | 1 | STONEWARE, WESTERWALD, FRAGMENT, PURPLE |

| AG | 1 | STONEWARE, FULHAM SW, FRAGMENT, * |

| AH | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, BOWL |

| AI | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, STEM, 5/64 |

| AJ | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, DOMESTIC, STEM |

| AK | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, CASE BOTTLE |

| AL | 1 | GLASS, CLRLESS LEAD, FRAGMENT, TABLE GLASS |

| AM | 4 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE |

| AO | 3 | BONE, FAUNAL SPECIMEN |

| AP | 1 | SHELL, SHELL |

| AQ | 1 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT, WITH LEAD GLAZE, USED AS KILN FURNITURE |

| AR | 6 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AT | 1 | IRON, NAIL, 2 TO 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AU | 2 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AV | 9 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AA | 12 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AB | 1 | CHARCOAL, CHARCOAL |

| AA | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE, * |

| AB | 23 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AC | 1 | WOOD, ORGANIC SUBST |

| AD | 1 | GREY CHERT, DEBITAGE, FLAKE FRAG/SHAT, NON-CORTICAL |

| AE | 40 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AF | 1 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT, PAN TILE |

| AG | 1 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AA | 1 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AB | 1 | DETACHED GLAZE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AC | 1 | STONEWARE, WESTERWALD, FRAGMENT, SPRIG MOLDED |

| AD | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINDOW GLASS |

| AE | 1 | GLASS, CLRLESS LEAD, FRAGMENT, TABLE GLASS, * |

| AF | 1 | QUARTZ, DEBITAGE, FLAKE FRAG/SHAT, NON-CORTICAL |

| AG | 2 | MARL, MARL |

| AH | 32 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AI | 4 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT |

| AJ | 1 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT, PROBABLE PAN TILE |

| AK | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, LOCAL |

| AL | 46 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AM | 1 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AN | 2 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AA | 2 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AB | 1 | MARL, MARL |

| AC | 1 | QUARTZ, STONE, UNWORKED |

| AD | 2 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AE | 1 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AA | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE, * |

| AB | 2 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, BOWL |

| AC | 8 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AD | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, DOMESTIC, STEM |

| AE | 2 | MARL, MARL |

| AF | 27 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AG | 1 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, FRAGMENT |

| AA | 1 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT, PAN TILE |

| AB | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE, * |

| AC | 1 | COAL, COAL |

| AD | 3 | MARL, MARL |

| AA | 1 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AA | 1 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, PAINTED UNDER, BLUE |

| AB | 1 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, MISSING GLAZE |

| AC | 1 | REFINED EARTHEN, CREAMWARE, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED, * |

| AD | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE |

| AE | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED |

| AF | 9 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AG | 1 | STONEWARE, FULHAM SW, FRAGMENT |

| AH | 1 | STONEWARE, FRECHEN BROWN, FRAGMENT |

| AI | 2 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, STEM, ONE IS 5/64, ONE IS 7/64 |

| AJ | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, BOWL |

| AK | 1 | GLASS, COLORED, FRAGMENT, CONTAINER, GREEN |

| AL | 1 | GLASS, CLRLESS LEAD, FRAGMENT, TABLE GLASS |

| AM | 2 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE |

| AN | 2 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT |

| AO | 5 | MARL, MARL |

| AP | 1 | SHELL, SHELL |

| AQ | 1 | SLAG, SLAG/CLINKER |

| AR | 48 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AS | 3 | IRON, NAIL, 2 TO 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AT | 7 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AU | 6 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AV | 1 | IRON, HOOK, FIREPLACE-TYPE |

| AW | 1 | IRON, KNIFE, BLADE, POSSIBLE KNIFE BLADE |

| AA | 1 | REFINED EARTHEN, CREAMWARE, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED, * |

| AB | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, BOWL |

| AC | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, STEM, IMMEASURABLE |

| AD | 2 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AE | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE |

| AF | 2 | SHELL, SHELL |

| AG | 1 | MARL, MARL |

| AH | 1 | STONEWARE, FULHAM SW, FRAGMENT |

| AI | 7 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AA | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AA | 1 | IRON, NAIL, 2 TO 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AA | 1 | REFINED EARTHEN, CREAMWARE, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED, * |

| AB | 2 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AC | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, STEM, 7/64 |

| AD | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, LOCAL |

| AE | 1 | SHELL, SHELL |

| AF | 15 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AG | 1 | IRON, UNID HARDWARE, ROLLED/SHEET |

| AH | 2 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AI | 3 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AA | 2 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AB | 1 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, PAINTED UNDER, BLUE |

| AC | 1 | REFINED EARTHEN, CREAMWARE, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED, * |

| AD | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE, LOCAL |

| AE | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, LEAD GLAZE |

| AF | 2 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AG | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, BOWL |

| AH | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, STEM, 7/64 |

| AI | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, DOMESTIC, ROULETTED, BOWL |

| AJ | 1 | BONE, FAUNAL SPECIMEN, BURNED |

| AK | 42 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AL | 1 | IRON, NAIL, 2 TO 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AM | 4 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AN | 7 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AA | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, N MIDLAND SLIP, FRAGMENT |

| AB | 2 | STONEWARE, FULHAM SW, FRAGMENT, * |

| AC | 5 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AD | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, BOWL |

| AE | 2 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, STEM, ONE IS 5/64, ONE IS IMMEASURABLE |

| AF | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, DOMESTIC, STEM |

| AG | 2 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE |

| AH | 5 | MARL, MARL |

| AI | 1 | SHELL, SHELL |

| AJ | 1 | QUARTZITE, STONE, UNWORKED |

| AK | 1 | BOG IRON, FRAGMENT |

| AL | 29 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AM | 1 | IRON, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AN | 1 | IRON, NAIL, 2 TO 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AO | 2 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AP | 1 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT |

| AA | 2 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINE BOTTLE, * |

| AB | 1 | GLASS, FRAGMENT, WINDOW GLASS |

| AA | 1 | IRON, PLANE/PART, FRAGMENT, UPPER PART OF BLADE |

| AA | 1 | STONEWARE, FULHAM SW, FRAGMENT, * |

| AC | 3 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AD | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, DOMESTIC, STEM |

| AE | 1 | CERAMIC, TOBACCO PIPE, IMPORTED, BOWL |

| AF | 1 | CERAMIC, FRAGMENT |

| AG | 1 | SHELL, SHELL |

| AH | 12 | BRICK, BRICKETAGE |

| AI | 3 | IRON, NAIL, 2 TO 4 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AJ | 3 | IRON, NAIL, FRAGMENT |

| AA | 3 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AB | 1 | EARTHENWARE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, MISSING GLAZE |

| AC | 1 | DETACHED GLAZE, TIN ENAMELLED, FRAGMENT, UNDECORATED |

| AD | 1 | COARSE EARTHENW, COARSEWARE, FRAGMENT, UNGLAZED, LOCAL |

| AE | 1 | STONEWARE, FULHAM SW, FRAGMENT, * |