Clothes for the People, Slave Clothing in Early Virginia

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation - 0409

Collections Division

Williamsburg, Virginia,

1988

CLOTHES FOR THE PEOPLE,

SLAVE CLOTHING IN EARLY VIRGINIA

OCCASIONAL PAPERS FROM THE EDUCATION DIVISION COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION

CLOTHES FOR THE PEOPLE:

SLAVE CLOTHING IN EARLY VIRGINIA

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Collections Division

Williamsburg, Virginia,

1988

"Clothes for the People"

Slave Clothing in Early Virginia

Article submitted to the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts for fall, 1988 or early 1989 issue.

Eighteenth century Virginia had evolved a society characterized by great disparity — human beings enslaved by men writing eloquent arguments for freedom; mansion houses surrounded by slave huts; elegant assemblies and barefoot black children. Ebenezer Hazard, a visitor to Virginia in 1777, took note of the contrasts. While he observed that Virginians had elegant entertainments, and that the ladies at an assembly "made a brilliant Appearance," he added, "The Virginians, even in the City, do not pay proper Attention to Decency in the Appearance of their Negroes; I have seen Boys of 10 & 12 Years of Age going through the Streets quite naked, & others with only Part of a Shirt hanging Part of the Way down their Backs. This is so common a Sight that even the Ladies do not appear to be shocked at it. 1

Nowhere was social disparity more evident than in the clothes people wore, proclaiming status, or lack of it, through the style of the garment, the fabric and color selection, the amount of clothing required to be "properly dressed," even the subtlety of posture, achieved both through training and force of tight stays. Virginians, apparently, were particularly apt to judge people by their appearance. Peter Collinson counselled someone contemplating a visit to the colony: 2

…these Virginians are a very gentle, wellÂdressed people—and look, perhaps, more at a man's outside than his inside. For these and other reasons, pray go very clean, neat, and handsomely dressed, to Virginia. 2

Although white settlers and visitors could exercise some selection in the clothing they brought to the colony, "New Negroes," as recently-imported slaves were called, arrived by ship with only the few clothes and ornaments allowed by their captors. William Hugh Grove described the wretched conditions in 1732:

The men are Stowed before the foremast, then the Boys between that and the main-mast, the Girls next, and the grown Women behind the Missen. The Boyes and Girles [were] all Stark naked; so Were the greatest part of the Men and Women. Some had beads about their necks, arms, and Wasts, and a ragg or Piece of Leather the bigness of a figg-Leafe. And I saw a Woman [who had] Come aboard to buy Examine the Limbs and soundness of some she seemed to Choose. Dr. Dixon…bought 8 men and 2 women…and brought them on Shoar with us, all stark naked. But when [we had] come home [they] had Coarse Shirts and afterwards Drawers given [to] them.33

Considering the wrenching experience these people had just experienced, being given clothes that were to them foreign in style and feel may have been among the least of their concerns, but clothing and ornaments are a powerful symbol of cultural and personal identity, and the new clothes were perhaps one more reminder of the transition in their lives. A ballad originally composed between 1656-1671 depicting the experience of a white convict servant sent to Virginia suggests the symbolic importance of clothing:

At last to my new master's house I came,

At the town of Wicocc[o]moco call'd by name,

Where my Europian clothes were took from me,

Which never after I again could see.A canvas shirt and trowsers then they gave,

4

With a hop-sack frock in which I was to slave:

No shoes nor stockings had I for to wear,

No hat, nor cap, both head and feet were bare.

Thus dress'd into the Field I nex[t] must go,

Amongst tobacco plants all day to hoe,

…

We and the Negroes both alike did fare.

English print sources clearly show the importance of clothing to indicate status. A mid-eighteenth century tobacco label shows slaves wearing only loin cloths packing tobacco into barrels for shipment alongside white gentlemen wearing the full

Snuff handkerchief (detail) England, plate printing in blue on linen, 1770-1785. The corner of the handkerchief shows a convict servant in jacket and long trousers, banished to America to work alongside a slave in the tobacco fields. 26 ¾" x 29 ½" Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1950-104

Snuff handkerchief (detail) England, plate printing in blue on linen, 1770-1785. The corner of the handkerchief shows a convict servant in jacket and long trousers, banished to America to work alongside a slave in the tobacco fields. 26 ¾" x 29 ½" Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1950-104

Tobacco paper, line engraving on paper, ca. 1750, 3 x 5". Arents Collections, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

4

complement of clothing proper to their status: shoes, stockings, a well-tailored three-piece suit (consisting of knee breeches, waistcoat and coat), a shirt with stock, wig and hat. Absence of clothing was acceptable for blacks when it would have been unthinkable for white adults, as we have seen in the quote above from Grove, in which the white women are described boarding the ship to inspect newly-arrived slaves who wore little or no clothing. Historians have pointed out that racism allowed white slaveholders to view blacks and Indians as somehow sub-human, thereby providing the justification for their enslavement.5 This helps to explain why the naked children in the streets observed by travellers to Virginia went seemingly unnoticed by the proper white ladies of the town. Laws codified this growing belief in the innate inferiority of blacks; in 1705 it was forbidden "to whip a christian white servant naked, without an order from a justice of the peace." Referring to this law and how the colonists justified it, Edmund Morgan observed, "Nakedness, after all, was appropriate only to a brutish sort of people, who had not achieved civility or Christianity."6

Tobacco paper, line engraving on paper, ca. 1750, 3 x 5". Arents Collections, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

4

complement of clothing proper to their status: shoes, stockings, a well-tailored three-piece suit (consisting of knee breeches, waistcoat and coat), a shirt with stock, wig and hat. Absence of clothing was acceptable for blacks when it would have been unthinkable for white adults, as we have seen in the quote above from Grove, in which the white women are described boarding the ship to inspect newly-arrived slaves who wore little or no clothing. Historians have pointed out that racism allowed white slaveholders to view blacks and Indians as somehow sub-human, thereby providing the justification for their enslavement.5 This helps to explain why the naked children in the streets observed by travellers to Virginia went seemingly unnoticed by the proper white ladies of the town. Laws codified this growing belief in the innate inferiority of blacks; in 1705 it was forbidden "to whip a christian white servant naked, without an order from a justice of the peace." Referring to this law and how the colonists justified it, Edmund Morgan observed, "Nakedness, after all, was appropriate only to a brutish sort of people, who had not achieved civility or Christianity."6

The absence of stays among the clothing assigned to female field slaves is another case in point. The wearing of stays was considered essential for the properly dressed lady in the eighteenth century Anglo-American culture. Stays did much more than just shape the figure into a cone from waist to bust or mould a tiny waistline. In fact, eighteenth century stays did less to restrict the waist than many mid-nineteenth century

Woman's stays, England, mid-eighteenth century, wool satin lined with linen, stiffened with whalebone and edged with leather. OW 33". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1966-188.

5

corsets. Stays were laced onto very young girls and many little boys to encourage proper erect posture, push the shoulders back and down, and help teach ways of moving suitable for ladies and gentlemen. The resulting eighteenth century fashionable shape, even for men, was one of sloping shoulders and very narrow backs. This exaggerated stance shows up in portraiture, but was not just a painterly convention; it is confirmed by the very narrow, flat backs of surviving eighteenth century garments. Although accounts suggest that some Virginia women, especially those in backwoods areas, left off their stays in the hottest summer months, this was not quite suitable behaviour for a lady, and certainly not for more formal situations. Philip Vickers Fithian was surprised enough to see Mrs. Robert Carter without her stays one October day in 1774 that he noted in his journal, "To day I saw a Phenomenon, Mrs. Carter without stays!" He added that she was not wearing them because of a pain in her breast.7 So important were stays to a woman's wardrobe that several British paintings show white women working in the fields wearing stays, even though their outer gowns have been removed.8 Plantation records reveal that the summer clothes of many female field slaves consisted only of a linen shift and somewhat heavier linen petticoat. Sarah Fouace Nourse wore a similar outfit in 1781 when trying to cope with the July heat on her plantation in Berkeley County, Virginia; she recorded in her diary, that it was very sultry, so after dinner she stayed "up stairs in only shift & petticoat till after Tea." It is instructive that Mrs. Nourse—

Woman's stays, England, mid-eighteenth century, wool satin lined with linen, stiffened with whalebone and edged with leather. OW 33". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1966-188.

5

corsets. Stays were laced onto very young girls and many little boys to encourage proper erect posture, push the shoulders back and down, and help teach ways of moving suitable for ladies and gentlemen. The resulting eighteenth century fashionable shape, even for men, was one of sloping shoulders and very narrow backs. This exaggerated stance shows up in portraiture, but was not just a painterly convention; it is confirmed by the very narrow, flat backs of surviving eighteenth century garments. Although accounts suggest that some Virginia women, especially those in backwoods areas, left off their stays in the hottest summer months, this was not quite suitable behaviour for a lady, and certainly not for more formal situations. Philip Vickers Fithian was surprised enough to see Mrs. Robert Carter without her stays one October day in 1774 that he noted in his journal, "To day I saw a Phenomenon, Mrs. Carter without stays!" He added that she was not wearing them because of a pain in her breast.7 So important were stays to a woman's wardrobe that several British paintings show white women working in the fields wearing stays, even though their outer gowns have been removed.8 Plantation records reveal that the summer clothes of many female field slaves consisted only of a linen shift and somewhat heavier linen petticoat. Sarah Fouace Nourse wore a similar outfit in 1781 when trying to cope with the July heat on her plantation in Berkeley County, Virginia; she recorded in her diary, that it was very sultry, so after dinner she stayed "up stairs in only shift & petticoat till after Tea." It is instructive that Mrs. Nourse—

Woman's linen shift, England, 1780-1800. Even among wealthy women, shifts were cut in a series of triangles and rectangles to avoid wasting fabric; contemporary records show they usually required 3 ½ yards of linen. OL 48", circumference at hem, 80". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1986-207.

6

a white woman—did not leave the privacy of her own upstairs in this comparative state of undress.9 Although stays were considered necessary and proper in eighteenth century society, from today's vantage point we might consider the slave women fortunate who did not have to wear such a hot and constricting garment. This is not to suggest that no black women wore stays; although the records are scanty, ladies' maids and house servants probably received stays, and one mulatto slave named Agnes or Aggie ran away from Norfolk wearing "a pair of stays with fringed blue riband"; she also had silver buckles in her shoes and silver bobs in her ears.10

Woman's linen shift, England, 1780-1800. Even among wealthy women, shifts were cut in a series of triangles and rectangles to avoid wasting fabric; contemporary records show they usually required 3 ½ yards of linen. OL 48", circumference at hem, 80". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1986-207.

6

a white woman—did not leave the privacy of her own upstairs in this comparative state of undress.9 Although stays were considered necessary and proper in eighteenth century society, from today's vantage point we might consider the slave women fortunate who did not have to wear such a hot and constricting garment. This is not to suggest that no black women wore stays; although the records are scanty, ladies' maids and house servants probably received stays, and one mulatto slave named Agnes or Aggie ran away from Norfolk wearing "a pair of stays with fringed blue riband"; she also had silver buckles in her shoes and silver bobs in her ears.10

Appearance and ornamentation are not determined entirely by clothing, but by other physical characteristics, as well. Some markings could be a constant reminder of the slave's cultural origins, as in the case of runaway Will, who had "his Teeth filed, and has his country Marks in his Face" or George, "marked in the face as the Gold coast slaves generally are."11 other markings were less-than-subtle reminders of the institution of slavery, as with Boston, who was "scarrified by whipping" or Annas, a "very white" mulatto woman, who was branded on her cheeks with E and R, initials of her master Edward Rutland.12 Such mutilation was neither unknown nor illegal. Not a few slaves were branded after attempts to run away, and it was within the bounds of law to cut off toes or fingers of slaves as punishment for incorrigibility.13

Before slavery was outlawed in England in 1772, some 7 slave owners had their household slaves wear a silver collar engraved with the owner's name and address. Such a collar can be seen on a slave boy in plate two of Hogarth's Harlot's progress.14 Affluent Americans copied this fashion. In the portrait of young Maryland resident, Henry Darnall III, painted by Justus Englehardt Kuhn, a black servant wears a wide silver collar about his neck. In Virginia, the estate of Colonel Thomas Bray included "a Silver Collar for a Waiting Man" which was sold at auction near Williamsburg in 1751.15 A neck ornament of precious metal that might in one context be a mark of wealth in the wearer instead indicates servitude, which by extension enhances the status of the owner.

Elaborate suits of livery can also be seen as examples of symbolism. Worn by highly visible male servants—men accompanying carriages, footmen, waiters and the like—livery was an elaborate and expensive uniform whose symbolism was not lost on contemporaries. Livery was based on a gentleman's fashionable three-piece suit, but with the addition of certain prescribed elements. It was usually made of good quality wool in two contrasting colors based on the colors of the owner's coat of arms. The contrast of color might be accomplished by making collar and cuffs a different color, or by having a contrasting waistcoat. Livery was usually embellished with "livery lace," elaborate edging sometimes woven of silver or gold, but most often woven like narrow velvet ribbons in colored silks or wool with designs based on the customer's coat of arms. The buttons

"Henry Darnall III" by Justus Englehardt Kühn, Maryand, oil on canvas, ca. 1710. The black servant to the left of Henry Darnall is wearing a jacket and the silver collar of a waiting men. 37 ¼ X 30 1/8". Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore. 12.1.3.

"Henry Darnall III" by Justus Englehardt Kühn, Maryand, oil on canvas, ca. 1710. The black servant to the left of Henry Darnall is wearing a jacket and the silver collar of a waiting men. 37 ¼ X 30 1/8". Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore. 12.1.3.

Suit of livery, green and cream woolens trimmed with silk livery lace, England, 1810-1840. The livery lace, used lavishly on the coat and waistcoat, is woven with a repeating crest. Livery continued in traditional eighteenth-century style, like this example, long after men's clothing had changed in fashion. Coat length, 46 ½"; breeches waist 34". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1986-141, 1-3.

8

might also be molded with the owner's crest. Sometimes the trimming included a single shoulder knot resembling a military epaulet. Although livery was a European custom, it was widely practiced in the colonies and readily taken up by wealthy Virginians like George Washington, Robert Carter, and Landon Carter. Washington ordered materials for his red and white livery suits several times in the eighteenth century. In 1755 he ordered wool for two men's suits and matching "horse Furniture, with livery Lace, and the Washington Crest on the housing… " He added specific instructions as to size and style:

Suit of livery, green and cream woolens trimmed with silk livery lace, England, 1810-1840. The livery lace, used lavishly on the coat and waistcoat, is woven with a repeating crest. Livery continued in traditional eighteenth-century style, like this example, long after men's clothing had changed in fashion. Coat length, 46 ½"; breeches waist 34". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1986-141, 1-3.

8

might also be molded with the owner's crest. Sometimes the trimming included a single shoulder knot resembling a military epaulet. Although livery was a European custom, it was widely practiced in the colonies and readily taken up by wealthy Virginians like George Washington, Robert Carter, and Landon Carter. Washington ordered materials for his red and white livery suits several times in the eighteenth century. In 1755 he ordered wool for two men's suits and matching "horse Furniture, with livery Lace, and the Washington Crest on the housing… " He added specific instructions as to size and style:

The Servants that these Liverys are intended for, are 5 feet, 9 Inc. and 5F. 4In. high and proportionably made[.] I wou'd have you choose the livery by our Arms; only, as the Field of the Arms is white. I think the Cloaths had better not be quite so but nearly likely the inclos'd. The trimmings and Facings of Scarlet and a Scarlet Waistcoat, the Cloath of w'ch to be 12s 6 pr. yd. If livery Lace is not quite disus'd, I shou'd be glad to have these cloaths laced. I like that fashion best; and two Silver lac'd hats for the above Livery's.16In August of 1764 he ordered another suit of livery, this time made of wool "shagg," a napped, shaggy wool, lined with red "shalloon," a thin glazed wool. The coat's collar and waistcoat

Livery coat, England, 1790-1800. The green broadcloth coat is trimmed with red wool and livery lace in matching colors of red and green; the lining is red twill worsted, OL 45 ½". Colonial [...]

Livery coat, England, 1790-1800. The green broadcloth coat is trimmed with red wool and livery lace in matching colors of red and green; the lining is red twill worsted, OL 45 ½". Colonial [...]

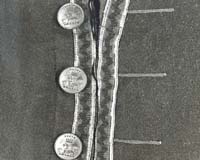

Detail from the front of the livery coat. The livery lace is uncut velvet, woven ¾ inches wide, the same width ordered by George Washington in 1784; the buttons are gilt brass, with the crest from an unknown coat of arms. The buttons are stamped "Hunter & Co., 93 [or 98] St. Martin's Lane, London," probably for John Hunter, mercer and button-seller at 93 St. Martin's Lane beginning in 1791 (Kent's Dictionary.) Colonial Williamsburg

9

worn beneath were to be red; all were to be trimmed with livery lace, though two months later Washington changed his mind and cancelled the order for the lace.17 In 1784 Washington ordered 70 yards of red and white livery lace that was to be between 3/4 and one inch wide.18

Detail from the front of the livery coat. The livery lace is uncut velvet, woven ¾ inches wide, the same width ordered by George Washington in 1784; the buttons are gilt brass, with the crest from an unknown coat of arms. The buttons are stamped "Hunter & Co., 93 [or 98] St. Martin's Lane, London," probably for John Hunter, mercer and button-seller at 93 St. Martin's Lane beginning in 1791 (Kent's Dictionary.) Colonial Williamsburg

9

worn beneath were to be red; all were to be trimmed with livery lace, though two months later Washington changed his mind and cancelled the order for the lace.17 In 1784 Washington ordered 70 yards of red and white livery lace that was to be between 3/4 and one inch wide.18

Once our eyes are attuned to the appearance of livery, we can more easily analyze the symbolism of the clothing in a painting of a servant and his master. Young Charles Calvert of Baltimore was painted by John Hesselius with a black servant kneeling beside the young subject. Not only do their postures suggest a gulf between the young men, but their clothing reinforces the differences between their lives. Charles is wearing a suit not typical of eighteenth century daily wear; his coat with its slashed sleeves and lace cuffs turned back toward his elbows is "Vandyke" dress, a style taken from the portraits of Vandyke a century earlier, and considered fashionable wear for portraits during the second half of the eighteenth century. In Britain, Zoffany painted the entire family of Sir William Young wearing Vandyke styles.19 Vandyke costume would suggest to the eighteenth century viewer that the patrons of the portrait were aware of the contemporary styles in portraiture; it was also intended to dignify the sitter by recalling earlier traditions. Although he appears to modern eyes to be very finely clothed, the young black man's subservient kneeling position is further emphasized by his wearing the suit of a servant, in this case a yellow livery trimmed with black collar and cuffs and edged with

"Charles Calvert" by John Hesselius, Oil on Canvas, 1761, 50 ¼ x 39 7/8". Baltimore Museum of Art, Gift of Alfred R. and Henry G. Riggs in Memory of General Lawrason Riggs. 1941.4.

10

parti-color livery lace.

"Charles Calvert" by John Hesselius, Oil on Canvas, 1761, 50 ¼ x 39 7/8". Baltimore Museum of Art, Gift of Alfred R. and Henry G. Riggs in Memory of General Lawrason Riggs. 1941.4.

10

parti-color livery lace.

That livery was perceived as a mark of servitude can be inferred from a white servant's refusal to wear it. William Holland, a Parson from Somerset, England, records in his journal that "Mr Charles my man it seems does not chuse to wear a Livery so he is to go at the month's end."20 It is impossible for us to know what liveried slaves thought about their clothing. It was finer than the coarse, scratchy clothing of field slaves, and may well have carried an element of status within the slave community, especially as it indicated that the wearer held a job superior to working in tobacco fields.

Household servants—even those in livery—could not always count on staying in their positions, and were sometimes transferred to less desirable work. Plantation owners did not allow economically valuable workers to be idle. George Washington gave specific instructions when he learned that his spinners were out of wool: "They must not be idle; nor ought the Sewers to have been so when they were out of thread: If they can find no other work, let them join the out door hands."21 Writing from Philadelphia in 1796, Washington sent instructions that Cyrus was to be prepared to come back into household service, get new clothes, and even change to a more acceptable hair style:

I would have you again stir up the pride of Cyrus; that he may be the fitter for my purposes against I come home; sometime before which (that is as soon as I shall be able to 11 fix on the time) I will direct him to be taken into the house, and clothes to be made for him. In the meantime, get him a strong horn comb and direct him to keep his head well combed, that the hair, or wool may grow long.22

The style and quality of clothing given to slaves depended upon their occupation, which we have seen could change quickly, as well as their perceived importance and visibility to the white community. Household servants and personal body servants fared best. Thomas Jefferson suggested that household servants received special treatment in a letter to his overseer, Edmund Bacon, early in the nineteenth century: "Clothes for the people are to be got from Mr. Higginbotham, of the kind heretofore got. I allow them a best striped blanket every three years…Mrs. Randolph always chooses the clothing for the house servants; that is to say, for Peter Hemings, Burwell, Edwin, Critta, and Sally.". He added that the rest of the servants were clothed in "Colored plains" or "cotton."23

If male household servants were not given livery, they wore suits based on those worn by white gentlemen. Walton, who had worked as a waiting man, ran away with four shirts, two suits of clothes, one with gilt buttons, along with "a Surtout Coat, Velvet Cap, Hat, and every Thing else suitable for a Waitingman."24 Females in similar positions were often clothed like white maids; Martha Washington's maids wore gowns of 12 relatively fine fabrics such as calico and linen.25

Although tradition has it that slaves routinely received "hand-me-down" clothing from whites, this was not the case for most Virginia slaves. Those documents proving that clothing was handed down during the eighteenth century suggest that only favored or close personal servants—in other words, a small percentage of the total slave population—benefitted from the practice. Giving cast-off clothing to personal servants was an English tradition, and some colonists extended it to the blacks in their close employ. In South Carolina, there is reference in 1822 to "those waiting men who receive presents of old coats…from their masters."26

The tradition that slaves received hand-me-downs grew stronger in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. A case in point is Sy Gilliat, a fiddler who played for white audiences in Richmond and vicinity during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In 1860 Sy's costume was described as being "an embroidered silk coat and vest of faded lilac, small clothes [i.e. breeches], and silk stockings." The author explained, "This court-dress was coeval with the reign of Lord Botetourt, and probably part of the fifty suits which, (according to the inventory he left) constituted his wardrobe…"27 By 1923, the author of Richmond, Its People and Its Story stated the tradition more strongly: "When he [Gilliat] and his fiddle graced formal occasions he is said to have appeared in one of the fifty court costumes of Lord Botetourt who had in Sy's youth been 13 his master."28 Although no slave named Sy, Simon or Cyrus is recorded in the service of Botetourt, it is possible he changed his name after leaving service—or he may not have worked for the Governor at all!29

Nevertheless, we need not rule out the story of Sy's clothing, for the practice of distributing clothing to a few favored house servants is documented and may have been widespread. Mary Willing Byrd of Westover provided for her maid, Jenny Harris, in her 1813 will; according to the will, Jenny was to be emancipated "whenever she may chuse it." She was to receive a small bedstead with its bed, bedding and curtains, as well as "such of my wearing apparel as my children may think proper for her to have."30 Joseph Ball sent from London used clothing from his own wardrobe and that of his "man Aron" to be given to several of the slaves at Morattico in Lancaster County. Ball wrote, "The old Cloths must be disposed of, as follows: The Grey Coat Wastecoat & breeches, with brass buttons, and the hat to poor will: The stuff Suit to Mingo: and the Dimmity Coat & breeches and the knife in the pocket to Harrison: and Aron's Old Livery with one pair of the Leather breeches and one of the Linen frocks to Moses…." On another occasion he sent an old "banjan" (probably a banyan or dressing gown) and colored breeches, for Israel, black velvet breeches for Will, and another pair of breeches for Aaron, who was now residing in Virginia.31

However, the great majority of slaves did not receive their master's used clothing. Not only were there insufficient 14 hand-me-downs to supply the thousands of field slaves working on large Virginia plantations, such clothing would have been considered inappropriate in style and fabric for the majority of slaves who had to labor outdoors. Even the kindly Mary Willing Byrd charged her children with deciding which of her clothing was appropriate for Jenny to receive.

If liveried servants wore a very elaborate uniform, field slaves were allotted a uniform of another sort. Surviving accounts suggest that there was a sameness and recognizability in the clothing of field hands. Advertisements describe runaway men wearing clothes, "such as crop Negroes usually wear" or "the common dress of field slaves," the latter spelled out as being osnabrug shirts, cotton jackets and breeches, plaid hose, and Virginia made shoes.32 To understand this fully, we must explore the ways in which plantation owners acquired clothing for their slaves.

Although some planters used locally-woven cloth for their slaves' clothing, especially around the time of the Revolution, most of the materials for slaves' clothing in the eighteenth century were imported from England.33 A vast worldÂwide trade in textiles existed, being shipped from China, India and Europe to England, where by law they had to land before being transshipped to the colonies. Two types of textiles became very important as slave goods: coarse linens from Germany and Scotland such as Osnaburg and rolls; and inexpensive woolens from England, Wales and Scotland, such as plains, plaid and a

Detail from a merchant's sample' book, England, ca. 1800. A swatch of coarse, fuzzy woolen is labelled "plain," one of the fabrics exported to the colonies for slaves' winter clothing. The sample above is labelled "coating," one of the fabrics worn in Virginia by slaves and free men alike; the swatch below is broadcloth. Joseph Downs Manuscript Collection, Henry Francis duPont Winterthur Museum, mss. no. 69 x 216.

15

woolen textile with the unlikely name of "cotton." Local stores and planters ordered these textiles seasonally in large quantities. Robert Beverley bought most of his slaves' fabrics from a Liverpool supplier; in 1768 he ordered 1000 ells of German Osnaburg, 300 yards of Kendal Cotton, 100 yards of pladding "for negroe children" and "60 ready-made Fear nothing waistcoats of the cheapest color." He also ordered twenty-four dozen buttons, half of which were to be white metal in two sizes and another twelve dozen to be horn molds for coat buttons without shanks. The horn molds would have been covered with fabric which, when drawn up around the mould, forms its own shank on the back; one sees this type of covered button on men's period wool coats. In July 1772, Beverley again ordered materials for the approaching winter season: 300 yards of Kendal Cotton, 100 yards of white plains for children, 500 yards each of British and German Osnaburg, thread, 12 dozen pair of plaid stockings, and for the "servants," a dozen coarse worsted stockings, another dozen brown thread (linen) stockings and 20 pair of shoes in "large & small Mens Size."34

Detail from a merchant's sample' book, England, ca. 1800. A swatch of coarse, fuzzy woolen is labelled "plain," one of the fabrics exported to the colonies for slaves' winter clothing. The sample above is labelled "coating," one of the fabrics worn in Virginia by slaves and free men alike; the swatch below is broadcloth. Joseph Downs Manuscript Collection, Henry Francis duPont Winterthur Museum, mss. no. 69 x 216.

15

woolen textile with the unlikely name of "cotton." Local stores and planters ordered these textiles seasonally in large quantities. Robert Beverley bought most of his slaves' fabrics from a Liverpool supplier; in 1768 he ordered 1000 ells of German Osnaburg, 300 yards of Kendal Cotton, 100 yards of pladding "for negroe children" and "60 ready-made Fear nothing waistcoats of the cheapest color." He also ordered twenty-four dozen buttons, half of which were to be white metal in two sizes and another twelve dozen to be horn molds for coat buttons without shanks. The horn molds would have been covered with fabric which, when drawn up around the mould, forms its own shank on the back; one sees this type of covered button on men's period wool coats. In July 1772, Beverley again ordered materials for the approaching winter season: 300 yards of Kendal Cotton, 100 yards of white plains for children, 500 yards each of British and German Osnaburg, thread, 12 dozen pair of plaid stockings, and for the "servants," a dozen coarse worsted stockings, another dozen brown thread (linen) stockings and 20 pair of shoes in "large & small Mens Size."34

There were periodic problems with the goods being delayed. George Washington still had not received his winter clothing by the end of September, 1757; he wrote, "I have waited till now, expecting the arrival of my Negros Cloaths from Great Britain; but as the season is advancing, and risks attending them, I can no longer depend [upon the shipment]… " He was forced to get 250 yards of osnaburg, 200 yards of cotton, "plad" 16 hose and thread from a local store.35 Virginia plantation records indicate that most field slaves received only one winter suit a year; therefore, a delay would force them to wear last year's suit (if it was not worn out) until the new winter materials came in. Even when delays did not occur, some slaves must have felt the first cold weather keenly. Robert Carter specified that his slaves' winter clothes were not to be delivered until the first Monday in December.36 Joseph Ball was more concerned about when clothes were received; his instructions to his nephew specified that the supplying "must be done in Good time; and not for the Winter to be half over before they get their winter Cloths, and the summer to be half over before they get their summer Cloths; as the Common Virginia fashion is."37

Once the hundreds of yards of textiles came in, they had to be made up into clothing. Some planters like Joseph Ball and Nathaniel Burwell hired tailors to make the woolen clothing. Burwell hired John Grymes to make "35 Suits for Crop People @ 1/6" and paid an extra 6 shillings for putting pockets into them.38 Occasionally the planter's wives sewed some of the clothing themselves, especially in the case of smaller plantations; Sarah Fouace Nourse recorded that she cut out shirts and shifts and made jackets and petticoats for Cloe, one of her slaves.39 This practice continued into the third quarter of the nineteenth century, after the sewing machine had come into general use to make the task easier. A Mississippi woman used her new machine to make clothing and other Christmas gifts for 17 the slaves in 1860; Roxanna Chapin Gerdine wrote to Emily Chapin, "I can extol my sewing machine by the hour. My seamstress and I made one hundred sixty-five garments for the negroes in December—wool coats, pants, dresses and other garments besides thirty white boardered aprons for their Christmas gifts. They thought there never were such times. Had a tree on Christmas loaded with aprons, oranges, tobacco, and rag babies."40

Some slave holders like George Washington trained their female slaves to sew, especially linen shirts and shifts. In a letter of December 23, 1792, he complained that his "sewers" were working too slowly, producing only six shirts a week when their usual task was to make nine, and that one slave named Caroline had produced only five. Two months later, he wrote that the gardener's wife should have cut out the linens, instead of Caroline, whom he suspected of dishonesty and embezzlement of materials.41 Joseph Ball had some of the women skilled in sewing make their own and their children's clothing; he wrote in 1743/4, "Bess, Winny, Nan, Hannah, and Frank, must have their shifts, and Linen petticoats, and their Children's Linen, Cut out and thread and needles given them, and they must make them themselves…The rest of the folks, must have their Linen made by somebody that will make it as it should be."42

The fact that all the field hands in anyone season received a suit identical in fabric and color meant that there was a great deal of uniformity in the clothing, leaving little 18 if any room for personal expression through their wearing apparel unless individuals had access to dyestuffs or other textiles. Such was the case of three men who ran away from a plantation in Cumberland County, Virginia, "all clothed in good white plains, good osnabrugs shirts, and stockings made of the same sort of cloth as their clothes."43 It is unlikely that each slave was fitted personally or carefully for his or her suit, and the illÂfitting—even if new—clothing also set slaves apart from those who could afford to have their clothing personally sized or skillfully altered. Ready-made clothing ordered by the dozens—Fearnothing jackets, plaid hose made of cut-and-sewn wool fabric, and knitted Monmouth caps—also added to the impression of uniformity and less-than-perfect fit. Even George Washington's suits of livery were ordered by the men's heights, rather than detailed measurements. In some cases, the clothing had to be altered immediately, as with the stockings received by Edward Ambler for his slave women. Ambler wrote on December 7, 1767 regarding the clothing just received, "I am apprehensive the women's stockings will prove too small. I should therefore be glad if you would give out some slips of Kendall's Cotton and thread to make them larger."44 Ambler is obviously referring to plaid hose made of fabric, rather than knitted stockings; such woven stockings could be made larger by opening the seam and inserting a strip of Kendal cotton, a fabric similar to the wool used to make such stockings. The baggy stockings made of biasÂcut and seamed wool fabric were a far cry from the finely-knit 19 silk and linen stockings worn by the aristocracy, and even from the knitted wool and linen stockings worn by household servants.

If a slave's suit was ill-fitting at the beginning of the season, it was almost certainly stained, shapeless and ragged by the end of the season. Unless a slave was able to save a suit from the year before in wearable condition, he or she wore the same jacket and breeches or petticoat all winter. Washington's records suggest that slaves slept in their daytime clothing, especially during the winter season; during one of his surveying trips, he wrote "…as the Lodging is rather too cold for the time of Year, I have never had my cloths of[f] but lay and sleep in them like a Negro…"45

When workers were able to obtain scraps of fabric, they probably mended their own clothing when needed, but scraps must have been hard to come by. George Washington was advised by Anthony Whitting that many bags (probably grain or flour sacks) had been stolen, and Whitting recommended that the bags be marked on both sides and that "…Coarse Sacking of European Manufacture (which a Negro could not mend his Cloaths with without a discovery) might answer…"46 Textiles were valuable in the eighteenth century on all social levels, and must have been even more so to slaves, some of whom were not even allowed to cut out their own linens for fear they would steal material or waste fabric personalizing their garments. Along with clothing he sent for four male slaves, Joseph Ball sent rags which he directed should be distributed as his nephew saw fit; these may have been 20 used for mending purposes.47

For summer, female slaves who worked outdoors received an extra linen petticoat to wear with their shift; men got a pair of summer breeches or trousers to wear with a shirt; both sexes would have worn their last winter's wool jacket if it got cool during the summer season. Most planters whose records survive gave each field slave two shirts or shifts per year, though Landon Carter made his slaves provide their own extra shirt: "My people always made and raised things to sell and I oblige them [to] buy linnen to make their other shirt instead of buying liquor with their fowls."48 Richard Bennett of Nansemond County was somewhat more generous with his slaves; in addition to the typical yearly ration of two shirts or shifts, a waistcoat, breeches or petticoat, and summer clothes, he added a coat for the men, caps and aprons for the women, and two pairs of shoes, instead of one pair. His will of 1750 reads:

all the said negroes both young and old shall yearly and every year be well sufficiently and warmly clothed vizt: the men and Boys Two Shirts of best Double Sprigg Ozenbriggs or other good Linnen, one waistcote and Breeches of best welch Cotton or penniston or Country made cloth, one coat of Kersey or mantu cloth, one pair of canvis breeches for summer, Two pairs of good shoes and stockings, one mill'd cap or felt hatt and 21 the Women and Girls with two Shifts of best Double Sprigg ozenbriggs or good Linnen, one waistcoat and Petticoat of best welch cotton or Penniston or Country made cloath, Two white Linnen caps, two aprons of check linnen, two pair of good shoes and stockings, one Petticoat of canvis or good Ozenbrigs or other good Linnen for Summertime, and the Children to have each of them Frocks for winter of good Cotton or Country made cloth and for summer frocks of strong brown linnen…49

Most planters appear to have made an effort to provide shoes for the adult slaves, and Bennett was somewhat more generous than others in giving each person two pairs of shoes. Joseph Ball instructed his nephew that all the workers should have "Good strong" shoes and stockings, but "they that go after the creatures or much in the Wet, must have two pair of shoes."50 Washington's weekly reports for 1787 indicate that some slaves did not work because their shoes were being mended; one boy was "confined 6 days for want of Shoes."51 Nevertheless, some slaves probably worked barefoot. In 1732, William Hugh Grove reported that "the Negroes at the Better publick houses must not Wait on You unless in Clean shirts and Drawers and feet Washed," implying that they were barefoot.52 Several males reported as runaways in the Virginia Gazette were described as having no shoes.

22We have seen that the suits of most outdoor slaves were made of the same materials for all, both men and women. Not only were the materials often imported, but the style of the suits also came from English and continental prototypes. During the period under discussion, status was shown in the clothing of whites by the choice of fabric and the quantity in which it was used, beautiful but non-functional trimmings like lace and needlework, elegance of style and fit, variety of styles, and the quantity of clothing one could afford. An upper-class woman's dress gown might take 20 yards of brocaded silk, made into a style with a long, full skirt, open to reveal still more elaborate fabric in a decorative petticoat; the sleeve ruffles falling gracefully over the elbows might be expensive lace or whitework embroidery. In contrast, a typical poor woman's outfit would use much less fabric, such as a short, loose gown of the type called a short gown or a more fitted waistcoat or jacket, all worn over a petticoat that was shortened to the ankles to make movement easier. This contrast was shown by the French encyclopedist Diderot. His engraved illustration for the Couturiere shows a woman wearing a fine gown contrasted with the servant in a "juste," or close-fitting body garment, worn with a short petticoat. As early as the seventeenth century, this type of two-piece suit was associated with poorer women. Randle Holme's 1688 Academy of Armory described the waistcoat as "the outside of a Gown without either stayes or bodies fastened to it; It is an Habit or Garment generally worn by the middle and lower

Woman's gown and matching petticoat of brocaded silk, worn in Virginia, but made from imported English silk, 1760-1770. The gown was worn by Elizabeth Dandridge Aylett Henley, sister of Martha Washington. OL 58 ½", waist approximately 24". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Gift of Mrs. R. Keith Kane. G1975-340, 1-2

Woman's gown and matching petticoat of brocaded silk, worn in Virginia, but made from imported English silk, 1760-1770. The gown was worn by Elizabeth Dandridge Aylett Henley, sister of Martha Washington. OL 58 ½", waist approximately 24". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Gift of Mrs. R. Keith Kane. G1975-340, 1-2

"Couturiere," (detail) contrasting "dress" clothing with servant's clothing, from the supplement to Diderot's Encyclopedia, France, line engraving on paper, 1777. 9 x 14 ¼", Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1966-221

23

sort of Women, having Goared skirts, and some wear them with Stomachers."53 Virginia planters adopted this European style as appropriate for their laboring slave women. The black women shown working in the fields painted by Latrobe are wearing very similar waistcoats, complete with "goared skirts," or tabs extending over the hips; the women's petticoats are short enough to be practical.

"Couturiere," (detail) contrasting "dress" clothing with servant's clothing, from the supplement to Diderot's Encyclopedia, France, line engraving on paper, 1777. 9 x 14 ¼", Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1966-221

23

sort of Women, having Goared skirts, and some wear them with Stomachers."53 Virginia planters adopted this European style as appropriate for their laboring slave women. The black women shown working in the fields painted by Latrobe are wearing very similar waistcoats, complete with "goared skirts," or tabs extending over the hips; the women's petticoats are short enough to be practical.

Men's dress clothing was the three-piece suit, consisting of knee breeches worn with a waistcoat beneath an outer coat; the shirt was fine bleached linen, often ruffled. In contrast the typical working man's outfit was a shorter form of coat, called a jacket or waistcoat, worn with breeches and a shirt of lesser-quality linen. In occupations where knee breeches with their tight bands around the leg were too constricting, trousers of various lengths and styles were adopted. Again, it was this working man's outfit that was used for slave laborers. Planters naturally transferred their conception of what poor working people customarily wore to clothing for their slaves, using cheap but relatively sturdy fabrics. Robert Carter III of Nomini Hall delivered just such clothing to his overseers on various plantations in November, 1773; the slave men and boys each received a waistcoat, a pair of breeches and two shirts each; the women and girls each received a jacket, petticoat and two shifts each. In addition, some people received shoes and plaid hose, and plaid fabric was delivered to make clothing for the little children.54 In a 1798 court case in

"An overseer doing his duty, Sketched from life near Fredericsburg" by Benjamin Latrobe, pencil, pen and ink and watercolor on paper, 1798, 7 x 10 ¼". Maryland Historical Society. III.21

"An overseer doing his duty, Sketched from life near Fredericsburg" by Benjamin Latrobe, pencil, pen and ink and watercolor on paper, 1798, 7 x 10 ¼". Maryland Historical Society. III.21

"George Booth as a Young Man" by William Dering. Oil on canvas, Virginia, 1740-1750. Booth, who lived in Gloucester County, Virginia, wears the three-piece suit and fine white shirt appropriate to a gentleman. 50 x 40". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1975-242.

24

which he sued his renter, Benjamin Berkely, Carter clearly specified the clothing he expected his slaves to receive:

"George Booth as a Young Man" by William Dering. Oil on canvas, Virginia, 1740-1750. Booth, who lived in Gloucester County, Virginia, wears the three-piece suit and fine white shirt appropriate to a gentleman. 50 x 40". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1975-242.

24

which he sued his renter, Benjamin Berkely, Carter clearly specified the clothing he expected his slaves to receive:

each male Negro 9 years old, and upwards to have one Waistcoat and breeches, one pair of Woolen Hose one pair of Summer Breeches, two oznabrigs shirts, one Blankett, and one pair of Shoes each, Each Female Negro 8 years old and upwards to have one Jackcoat and Petticoat one pair of Woolen Hose, two oznaburg shifts, one blankett, one summer Petticoat, one one [sic] pair of Shoes each, of the younger Negroes to have one Woollen frock, the males one shirt the females one shift, the summer Breeches and Petticoats & Shirts & Shifts for Children to be furnished the first Monday in June, the other cloathing & Blanketts to be furnished the first Monday in December.55Carter charged Berkely with failure to fulfill the terms of his rental agreement, including providing proper clothing for the 19 slaves, and the court ruled in his favor. Obviously, slaves were at the mercy of overseers and renters, even when their owners had every intention of providing sufficient clothing.

Throughout the Virginia records, there is strong indication that better clothing was assigned to productive workers than to those who were not contributing as much. 25 Economics took precedence over sentiment or humanity. Washington ordered two qualities of blankets and oznaburgh in 1795, adding "… let the better sort of Linnen be given to the grown people, and the most deserving; whilst the more indifferent sort is served to the younger ones and worthless." Regarding the blankets, the larger and better ones were to go to the grown people.56 Little children were among those who received clothing made of "indifferent" textiles.

Several travelers to America described the harsh life of slave children. During the 1790s, Julian Vrsyn Niemcewicz visited Washington's plantation where he entered a slave "hut." Niemcewicz observed that the "husband and wife sleep on a mean pallet, the children on the ground…"; he added later that "Gl. Washington treats his slaves far more humanely than do his fellow citizens of Virginia."57 A Frenchman who visited a slave home in Maryland looking for a drink of water observed "Some little Negro boys and girls, naked, [who] offered us a gourd that they had just filled. These children were thin, naps of tawny hair which covered their temples indicated lack of nourishment, or poor quality: their restless eyes fearfully looked us up and down."58 Nevertheless, most plantation owners did provide materials to clothe children, though in less quantity and of poorer quality than the clothing of the more economicallyÂvaluable workers. Children who had reached the age of 7 to 9 began to work alongside adults, and therefore wore clothing like their adult counterparts. Younger children of both sexes wore 26 dresses—usually called frocks—just as white children at the time did. Joseph Ball's slave children were to receive one "coat" and two shirts or shifts per year; the coat was to be of "Worser Cotton, or Plaiding, or Virginia Cloth" and the shirts and shifts of osnaburg. Ball also directed that baby clothes be made from old sheets or other old linen torn up for the purpose until he could send "proper" things at a later date.59 We have already seen that Robert Carter allowed little children only one shirt or shift, along with a woolen frock. Although Richard Bennet gave the children both summer and winter frocks, neither Ball nor Carter mentioned extra summer clothing or shoes for the children under working age, lending credence to traveller's accounts of some children being naked and barefoot.

Between the well-clothed personal servants on one hand and plantation field workers on the other lay a whole group of slaves who worked at other trades, and whose clothing reflected greater variety based on their occupations. The descriptions of clothing worn by runaway slaves advertised in colonial newspapers give a fascinating glimpse of what is otherwise largely unrecorded.

As we would expect, some runaways wore patched and mismatched clothing. Sypbax, a blacksmith "lately bought" from Maryland, ran away from Middlesex county wearing a brown cloth coat with "two patches on the left Side of the Back sewed in with white Thread;" he also took striped Virginia cloth breeches, several brown linen and white shirts, and a waistcoat.60 In

Two advertisements for run away slaves. Will retains the facial markings from his homeland, where he was attempting to return. Will's clothing is typical of what a field slave would have at the end of the summer when he ran away; he is wearing linen short trousers, his summer pants, but carried away an old cotton (i.e. woolen) jacket, possibly his last winter's wear. Jude is described as "very knowing" about house business, including sewing, and has a variety of clothing "too tedious to mention." Virginia Gazette, Purdie and Dixon, October 20, 1768. Virginia Historical Society; photostat at Colonial Williamsburg.

27

addition to the typical cotton waistcoat and breeches, a runaway named Jack had a coarse felt hat with part of the crown burned.61 Sterling, who had been born in the West Indies and was scarred from severe whipping, had a jacket of a bluish or purple color, "the jacket being too narrow, had a piece of cloth put in to widen it at the neck and shoulders;" in addition to the osnaburg shirt and breeches he was wearing, Sterling also took his blanket. 62 Sixteen-year-old Billy was colorfully dressed in a green plains waistcoat and breeches, worn with a brown cloth coat that had red sleeves and collar.63

Two advertisements for run away slaves. Will retains the facial markings from his homeland, where he was attempting to return. Will's clothing is typical of what a field slave would have at the end of the summer when he ran away; he is wearing linen short trousers, his summer pants, but carried away an old cotton (i.e. woolen) jacket, possibly his last winter's wear. Jude is described as "very knowing" about house business, including sewing, and has a variety of clothing "too tedious to mention." Virginia Gazette, Purdie and Dixon, October 20, 1768. Virginia Historical Society; photostat at Colonial Williamsburg.

27

addition to the typical cotton waistcoat and breeches, a runaway named Jack had a coarse felt hat with part of the crown burned.61 Sterling, who had been born in the West Indies and was scarred from severe whipping, had a jacket of a bluish or purple color, "the jacket being too narrow, had a piece of cloth put in to widen it at the neck and shoulders;" in addition to the osnaburg shirt and breeches he was wearing, Sterling also took his blanket. 62 Sixteen-year-old Billy was colorfully dressed in a green plains waistcoat and breeches, worn with a brown cloth coat that had red sleeves and collar.63

Some slaves had relatively large quantities and varieties of clothing, including articles considered fashionable in white society. Harry, a runaway slave who dealt in oysters and fish in Williamsburg, was wearing a black wig, in spite of the fetters he had on his legs.64 Sambo was clothed in the usual "Negro cotton" jacket and wide-kneed trousers, but he had a cocked-up hat and wore large buckles in his shoes.65 Joe, who had always been kept as a waiting man, had "a variety of cloaths," including two hats, one bound with black ferret and the other "laced," a blue Newmarket coat, several white shirts, a leaden colored cloth coat and vest, leather breeches, and several other items.66 Joseph Ball's manservant, Aron Jameson, was sent to Virginia from England supplied with a large cask of personal effects, including a mattress, feather bolster, coverlets, old bedclothes, three suits, one of them new, twelve shirts and neckcloths, and a violin.67 David Gratenread, a mulatto slave 28 who "plays the fiddle extremely well," carried away his fiddle and the following items:

a new brown cloth waistcoat, lapelled, lined with white taminy, and yellow gilt buttons, a new pair of buckskin breeches, gold laced hat, a fine Holland [linen] shirt, brown cut wig, and several old clothes that I cannot remember, except an old lapelled kersey waistcoat.68

Leather breeches, usually made of buckskin, were worn by men of all social levels, including Virginia slaves. It is possible that some of the breeches were made here; in 1766, James Terrell, by trade a leather breeches maker, ran away from George Cousins wearing a pair of leather breeches, possibly of his own making.69 However, many leather breeches were reaching Virginia stores from abroad. In 1766, Balfour and Barraud of Norfolk had London-made leather breeches for sale in their store; other Virginia merchants sold leather breeches imported from Philadelphia and Europe.70

Throughout the eighteenth century, leather breeches had been a favorite garment for everyday wear by English country gentlemen, especially for riding. They were not limited to the gentry, however, for working men also chose them for their durability in occupations where fabric breeches might have been more easily torn or snagged. By the last quarter of the eighteenth century, many of the styles formerly associated with

Leather breeches with a history of having been worn in Massachusetts by a slave, Jack Durfee, who later was able to purchase land near Plymouth Avenue in Taunton, 1760-1790. The breeches are of buff colored leather. Old Sturbridge Village. 26.40.21

29

countrymen and laborers were taken over into high style, and leather breeches became accepted in fashionable circles.71 In Virginia, they continued to be worn by workingmen for practical reasons, at the same time they were becoming more fashionable among the gentry. The leather breeches of Virginia slaves probably resembled those surviving at old Sturbridge Village with a history of having been worn by a free black man in Massachusetts; they are well constructed in a style similar to dress breeches, with fall front, side pockets, and buttons to a buckled knee band.

Leather breeches with a history of having been worn in Massachusetts by a slave, Jack Durfee, who later was able to purchase land near Plymouth Avenue in Taunton, 1760-1790. The breeches are of buff colored leather. Old Sturbridge Village. 26.40.21

29

countrymen and laborers were taken over into high style, and leather breeches became accepted in fashionable circles.71 In Virginia, they continued to be worn by workingmen for practical reasons, at the same time they were becoming more fashionable among the gentry. The leather breeches of Virginia slaves probably resembled those surviving at old Sturbridge Village with a history of having been worn by a free black man in Massachusetts; they are well constructed in a style similar to dress breeches, with fall front, side pockets, and buttons to a buckled knee band.

Trousers—which show up in approximately one out of eight slave runaway ads—were another workingman's garment that later entered high style, and in various forms have continued to be worn by men to this day. Worn by sailors, peasants, convicts and other workers throughout the eighteenth century in Europe, trousers were a practical alternative to breeches with their tight-fitting bands below the knee. Virginia trousers were usually made of coarse linens, which added to the practicality, as they could be more easily washed than woolen breeches. Today usually thought of as long pants, the trousers worn in early Virginia came in a variety of lengths, ranging from just below the knee down to the shoe tops, and were sometimes very full—described as "wide or wide-kneed." Virginia craftsmen, both black and white, sometimes layered the full trousers over breeches; in 1777 a mulatto slave named James ran away wearing "leather breeches, and linen trousers over them."72 These

Leather breeches, detail of fall front and waist area. The waist measures about 30 inches.

Leather breeches, detail of fall front and waist area. The waist measures about 30 inches.

Leather breeches, detail of knee buttons and band. The leatherÂcovered buttons are fastened on by having the shanks pushed through holes in the leather; a leather thong is then pulled through the shank of each button to prevent their being torn off during strenuous work. The knee band is made to accommodate a knee buckle.

30

layered trousers probably resembled those worn by the man holding a spear in John Singleton Copley's "Watson and the Shark"; one clearly sees the man's knee breeches under very full, culotte-like trousers.

Leather breeches, detail of knee buttons and band. The leatherÂcovered buttons are fastened on by having the shanks pushed through holes in the leather; a leather thong is then pulled through the shank of each button to prevent their being torn off during strenuous work. The knee band is made to accommodate a knee buckle.

30

layered trousers probably resembled those worn by the man holding a spear in John Singleton Copley's "Watson and the Shark"; one clearly sees the man's knee breeches under very full, culotte-like trousers.

Sometimes the slave runaways wore specialized clothing associated with their occupation. Peter ran away from the schooner Warwick near the mouth of the Potomac River wearing typical seamen's clothing—striped flannel trousers, a light colored pea jacket, and a straw hat covered with a "tarpawlin."73 Ben, a farmer and gardener who ran away from a plantation in Gloucester County took with him the "leather leggins" often worn by farmers.74 Several blacksmiths ran away with their protective aprons, including Jemmy, who "usually wears a leather apron."75 Isaac, a blacksmith employed on Thomas Jefferson's plantation later sat for his daguerreotype portrait around 1845 wearing his apron, probably resembling the one Jemmy wore.

The most typical suit of female runaways was the waistcoat or jacket worn with a matching petticoat, such as we

have seen assigned to field slaves. The suits were typically made of woolen, but several women wore linen, specially in the summer months. Lydia, who ran away in July of 1770, had a white osnabrug jacket and petticoat.76 . Another unidentified woman who ran away in July of 1786 wore an osnaburg waistcoat and petticoat; she was described as "very big with child."77

Although many slave women wore solid colored clothing, several of the ensembles described in runaway advertisements were made of

"Isaac," daguerreotype, ca. 1845. Isaac, formerly the blacksmith slave of Thomas Jefferson, is shown wearing his smith's apron. 2 1/8 x 3 ¼". Tracy W. McGregor Library, University of Virginia Library.

"Isaac," daguerreotype, ca. 1845. Isaac, formerly the blacksmith slave of Thomas Jefferson, is shown wearing his smith's apron. 2 1/8 x 3 ¼". Tracy W. McGregor Library, University of Virginia Library.

[Painting]

[Painting]

[Overall and] Detail, "Alexander Spotswood Payne and his Brother, John Robert Dandridge Payne, with their Nurse," oil on canvas, ca. 1790. Standing alongside young John in his child's shift, the young nurse is wearing a short petticoat and a striped waistcoat with the edges of her linen shift showing at the elbows and around the low neckline; she is also wearing beads. 56 x 69" Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, gift of Dorothy Payne. 53.24

31

striped Virginia or country c1oth.78

[Overall and] Detail, "Alexander Spotswood Payne and his Brother, John Robert Dandridge Payne, with their Nurse," oil on canvas, ca. 1790. Standing alongside young John in his child's shift, the young nurse is wearing a short petticoat and a striped waistcoat with the edges of her linen shift showing at the elbows and around the low neckline; she is also wearing beads. 56 x 69" Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, gift of Dorothy Payne. 53.24

31

striped Virginia or country c1oth.78

Besides the jacket-petticoat suits, some slave women wore gowns. We have already examined the clothing worn by Aggie, who had a pair of stays, a striped calimanco or worsted gown, silver buckles, and silver bobs (footnote 10.) Several runaways are described as having clothing "too tedious to mention." Jude, who was good at spinning, weaving, sewing and ironing, ran away in "her winter clothing," but she also had a blue and white striped Virginia cloth gown, a Virginia cloth copperas and white striped coat (probably a petticoat), and other clothes "too tedious to mention."79 A woman named Milla ran away in 1772 wearing "a short striped Virginia cloth gown and petticoat, oznabrig shift and bonnet." The subscriber added that she endeavors to pass for a free woman.80

Many slaves were able to obtain clothing similar to that of free men and women, and there is a suggestion in the records that better clothing might allow slaves to rise in status. Amy was accused of stealing an indenture and, her master suggested, had clothing to help her maintain a new identity; she "had when she went away silver buckles, and change of apparel, which makes her appear more like a free woman."81

Taken as a whole, a study of slaves' clothing through plantation records and runaway advertisements reveals several important facts.82 There was a great diversity within the slave community. Occupation and status were as obvious as they were in the free community. Eighteenth-century observers could 32 readily determine from the clothing and fabric whether a slave was working as an upper level household servant, a field hand or a craftsman. Status did not necessarily depend on how new the clothing was; a waiting man wearing an old suit handed down from his master was undoubtedly considered better dressed than a field hand with a brand new suit of coarse Negro cotton made exactly like all the other slaves' suits. In Virginia, fabric and trimming, rather than garment type, seem to have determined the status of the clothing. This is especially seen in the widespread use of coarse woolens such as "cottons" and plains for slaves' clothing; only a few white indentured runaways wore those fabrics which were so closely associated with slavery. The Anglo-European origin of slaves' clothing is clear, both in fabric and style. While the suits of field slaves were readily distinguished by type and textile, the clothing of male slave runaways working in skilled trades differed little from that of indentured white runaways, whether from choice or (more likely) because that was the clothing most readily available. Female runaway slaves wore a higher proportion of jacket-and-petticoat ensembles than did runaway white women; even so, some slaves did wear gowns, as we have seen.

Although a great deal is known about the clothing given to Virginia slaves, questions still remain. The plantation records and runaway advertisements were written by whites, and so express the intentions and interpretations of the white community. Perhaps the biggest unanswered questions are how

33

slaves and free blacks communicated their individual personalities and cultural heritage through clothing and accessories and how our twentieth-century eyes can detect those expressions. Self expression may have been too subtle to be detected and therefore condemned by whites, such as obtaining clothing in a color like red that had been favored for wearing apparel in Africa.83 Perhaps some field hands individualized their white suits by dyeing them with whatever dyestuffs could be found. Were natural materials used for adornment when jewelry could not be obtained? Were some of the caches of buttons found on archaeological sites of slave dwellings used—as the author suspects—as beads for adornment? We have, perhaps, one indication of personalized adornment in the early-nineteenth century descriptions of free blacks—both men and women—whose ears were "perforated for the purpose of wearing Ear rings."84 Perhaps individuality lay in how the clothing was worn, such as wrapping a handkerchief around the head to make a turban in African fashion, rather than wearing it around the neck and shoulders, as it was worn in the white community.85 Cultural expression could take the form of clothing left off, rather than worn; in some tribes, African children went seminude until puberty, and the reports of poor unclothed slave children in America may be missing the concept of nakedness as an extension of African custom.86 One would like to find a surviving garment made by one of the many black seamstresses working in Virginia. It is clear that even rural slaves working on plantations had

"Sallie Gladman, Mammy of Edward V. Valentine," daguerreotype, Richmond, Virginia, ca. 1850. 3 x 3 5/8." Sallie wears a large white handkerchief in the fashion of the late eighteenth century; she wears a white cap or headwrap. Lydia Jean Wares points out that mammies in the low country of South Carolina wore white turbans to mark their status; Sallie's head covering may stem

from a similar tradition in Virginia (Wares Dissertation [...

]

34

access to money through the sale of products they grew, but one wants to know more about what they purchased with their money. And where did poor people (both black and white) get their clothing? In England the buying and selling of used clothing was. a thriving trade. David Walker, who had been born in North Carolina to a slave father and a free mother, set up a successful used-clothing business after he moved to Boston, Massachusetts around 1827. 87 Perhaps time will turn up evidence of used clothing sales among blacks in eighteenth century Virginia.88 Indeed, time will hopefully answer many of our remaining questions about the clothing of enslaved people in America.

"Sallie Gladman, Mammy of Edward V. Valentine," daguerreotype, Richmond, Virginia, ca. 1850. 3 x 3 5/8." Sallie wears a large white handkerchief in the fashion of the late eighteenth century; she wears a white cap or headwrap. Lydia Jean Wares points out that mammies in the low country of South Carolina wore white turbans to mark their status; Sallie's head covering may stem

from a similar tradition in Virginia (Wares Dissertation [...

]

34

access to money through the sale of products they grew, but one wants to know more about what they purchased with their money. And where did poor people (both black and white) get their clothing? In England the buying and selling of used clothing was. a thriving trade. David Walker, who had been born in North Carolina to a slave father and a free mother, set up a successful used-clothing business after he moved to Boston, Massachusetts around 1827. 87 Perhaps time will turn up evidence of used clothing sales among blacks in eighteenth century Virginia.88 Indeed, time will hopefully answer many of our remaining questions about the clothing of enslaved people in America.

Linda Baumgarten

July 25, 1988

Footnotes

Glossary of Fabric and Clothing Terms

- Breeches

- Men's pants which ended just above or (more often) just below the knee, where they fastened around the leg with a band. The waist and center front closed with buttons, which were covered by a "fall" or flap during the second half of the century. Slaves' breeches were usually made of coarse, inexpensive woolens for the winter and linen for the summer; a few craftsmen had leather breeches like those worn by white workers.(See Fig. 16)

- Canvas, canvis

- Coarse, heavy linen.

- Coat

- (Male) A sleeved body-garment, worn as the uppermost layer of a three-piece suit(See Fig. 14); a great-coat was an overcoat worn for warmth. (Female) Coat usually refers to the woman's petticoat. (Children) Joseph Ball in 1744 instructed that the slave children should have a woolen "coat" and a shirt or shift; this may refer to a petticoat, but it more likely refers to a skirted frock made with sleeves and a front opening, of the type one sees in portraits of white children. (See Baumgarten, EighteenthÂCentury Clothing at Williamsburg, Williamsburg, published for Colonial Williamsburg, 1986, p. 75.) Ball may have been using an archaic term, which once meant an everyday loose tunic worn from the thirteenth century.

- Cotton

- (Depending on origin and type, described as Kendall, Welsh, and Negro cotton.) During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the term "cotton" was used in two contrasting ways; it indicated fabrics made of cotton fiber as well as woolens that were napped or "cottoned" to give a fuzzy appearance resembling the fluffy fibers of the cotton boll. The "cotton" used for 2 slaves' clothing and blankets during the period under discussion was usually the woolen fabric. Governor Dinwiddie reported in 1755 that "…The People in Y's Dom'n [Virginia] are supplied from G. B. with all sorts of Woolen Manufactories such as B'd [broad] Cloth, Kersey, Duffils, Cottons…" (R.A. Brock, ed. The Official Records of Robert Dinwiddie, Richmond, Pub. by the Virginia Historical Society, 1883, Vol. I, p. 385) This important trade in English woolens was disrupted just prior to and during the Revolution, but quickly resumed shortly after. In 1822, James Butterworth described the trade in Welsh and Kendal cottons from Britain, adding that they "are used chiefly for Negro clothing in America, and the West Indies…" (Quoted in Florence Montgomery, Textiles in America 1650-1870 New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1984, p. 206.) During the late eighteenth into the nineteenth centuries, the cotton plant gained greater importance in the southern economy, and some plantations could grow enough cotton to make shirts and shifts for slaves or to weave mixed wool and cotton fabrics for slaves' use.

- Crocus

- A coarse linen fabric used for slave's trousers.

- Drawers

- Men's pants. Although the term was usually used to indicate a man's undergarment, it was occasionally used to refer to an outer garment. William Hugh Grove, a visitor to Virginia in 1732, reported that blacks waiting on customers in the better public houses wore clean shirts and drawers. He also described the summer clothing of many gentry men as being a "White Holland Wast Coat & drawers." (VMHB Jan, 1977, p. 22 and 29) .

- Fearnothing, fearnaught

- A wool fabric that was sturdy and thick, 3 used to make men's jackets and waistcoats. Ready-made fearnothing jackets and other "Negro Cloathing" were available from London shops. (Aileen Ribeiro, Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe, 1715-1789, London: B. T. Batsford, 1984, p. 61-62.)

- Frock

- A child's dress worn by both sexes until boys were breeched; or a man's coat with a collar, such as the livery coat worn in the Calvert painting. (See Fig. 9)

- Gown

- The term used in the eighteenth century for a woman's dress. Gowns were not worn by field laborers, though household servants and some other upper-level slave women had gowns; typical fabrics used for slaves' gowns were linen, callico cotton, striped Virginia cloth and striped callimanco (worsted.) (See Figs. 11 and 12)

- Handkerchief

- A large square or triangle of cloth worn as a neckerchief by both men and women. When made of fine, sheer fabrics, handkerchiefs were worn as fashionable accessories by white women; less fine striped, printed and solid handkerchiefs were worn by working-class men and women. Slave women sometimes used the handkerchief as a head wrap, a fashion that originated in Africa and became identified with black women in America (See Fig. 22). Lydia Jean Wares quotes a slave, Osifekunde, who had been sold into slavery in 1756; his memoirs speak of West African women using red cloth to make a kerchief rolled like a turban around the head. European- and Indian-made handkerchiefs were reaching Africa through the textile trade, and it must have been natural for transported African women to continue this fashion in America, as handkerchiefs from the same sources reached America. 4 (Lydia Jean Wares, "Dress of the African-American Woman in Slavery and Freedom: 1500-1935" PhD Dissertation, Purdue University, 1981.) Betsey, who ran away in 1823, had her hair "platted" and had a handkerchief which she wore "round her head in sugar-loaf-form." (Richmond Enquirer, 21 March, 1823.)

- Jacket, jackcoat

- (Female) A woman's fitted bodice with ¾ or long sleeves and having a front closure, worn with a separate petticoat to form a work suit. Jackets and petticoats were the traditional work costume for European white women, and their use was quickly adopted for slave women. (See Fig. 12, 13, & 21)The name evolved from the "jack," a short, close-fitting garment worn by men and women during the 14th century; in 1798, Robert Carter still used the term "jackcoat" to refer to a garment for slave women. (Carter Vs. Berkeley, Dumfries Court records,— May, 1798.) The jackets worn by Virginia runaway women were primarily of unpatterned wool fabrics, though one is described as check'd and another striped in black and white. Charleston runaways also wore jackets, one of striped blue and white callimanco (worsted) with blue "Negro cloth" sleeves (Audrey Michie, "Goods Proper for South Carolina: Textiles Imported 1738-1742" Thesis University of North Carolina/Greensboro, 1978). The terms Jacket and Waistcoat were apparently used interchangeably in Virginia. (Male) A short coat worn with breeches as a workman's suit. (See Fig. 1, 5, 15) Jackets usually had sleeves, but a few runaway Virginia slaves were described as wearing jackets without sleeves. Although jackets were usually buttoned, one white runaway had a jacket that was laced instead 5 of buttoned. (Va. Gazette, Hunter, 20 October 1752.) Men could layer jackets for extra warmth; in 1774, Caesar ran away with "an upper jacket, made out of a blanket, and an under one, of negro cotton, without skirts°" (Virginia Gazette, Pinkney, 10 November, 1774.) As with women's clothing, the terms jacket and waistcoat were essentially interchangeable, a thesis supported by the phrasing of an order by south Carolinian Robert Pringle; he asked for an elaborately-trimmed "Jackett or Waist Coat" for his own wear. (Letter to David Glen in London, January 22, 1738/9. Walter B. Edgar, Editor, The Letterbook of Robert Pringle, Volume I, University of South Carolina Press, 1972, p. 63) )

- Kersey