Moody House Architectural Report, Block 2 Building 31 Lot 246Originally entitled: "The Moody House (Roper-Lee)"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1031

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

THE MOODY HOUSE

(Roper-Lee)

Block 2, Building 31, Colonial Lot #246

THE MOODY HOUSE

(Roper-Lee)

Block 2, Building 31, Colonial Lot #246

The Moody House, except for the two chimneys, which were left undisturbed to a point just above their second haunches, is totally reconstructed. In rebuilding the house, however, the exterior features of the old house were faithfully reproduced. It was at first thought that the old house should be preserved and repaired, but considerations of cost [and dilapidated condition of the structure] lead to its razing and reconstruction.

A. Edwin Kendrew, as head of the Architectural Department of Colonial Williamsburg, Inc. was responsible for the execution of the work.

Singleton P. Moorehead, Chief Designer.

Reconstruction started August, 1939

Reconstruction completed May, 1940

Measured Drawings of the house, dated July 14, 1939, were made largely by Thomas G. Little. Working Drawings are by Thomas G. Little, Ernest M. Frank, Ralph E. Bowers and Washington Reed. Drawings on this project were checked by Singleton P. Moorehead. Plan revisions to the house interior were made as sketches by Washington Reed in 1939. Further alterations were proposed on March 6, 1950; working drawings of alterations, signed by Carl Prior and checked by Ernest M. Frank, are dated June 15, 1950.

No architectural report on the Moody House was written when the house was studied and restored. This report is based upon scattered data gleaned from the measured drawings and the research notes. These materials have been compiled and arranged by A. Lawrence Kocher and Howard Dearstyne, September 12, 1950.

THE OLD MOODY HOUSE BEFORE ITS DEMOLITION, SHOWING THE LATE PORCH AND ATTACHED KITCHEN WHICH WERE OMITTED IN THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE BUILDING.

THE OLD MOODY HOUSE BEFORE ITS DEMOLITION, SHOWING THE LATE PORCH AND ATTACHED KITCHEN WHICH WERE OMITTED IN THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE BUILDING.

THE MOODY HOUSE

(Roper-Lee)

Block 2, Building 31, Colonial Lot #246

The Moody House, sometimes called, after its late owners, "The Roper-Lee House", is situated in Block 2 on Colonial Lot #246, on the south side of Francis Street. Lot #246 is identified as "Moody" on the Tyler Map of Williamsburg of about 1800, and on the Annie Galt and College Maps and it is also shown without identification on the Frenchman's Map [see Research Report in MS. by Miss Mary Stephenson, in the Department of Research and Record]. The Frenchman's Map is a most accurate guide to the location of buildings that existed in Williamsburg in the early 1780's. It shows two buildings on the Moody plot, joined together end-to-end, which makes their 2 length about three times their width. The house stands directly opposite the Dr. Barraud House on Lot #19. No outbuildings are shown on the Frenchman's Map, although foundations for several of these were uncovered by the archaeologists and an old smokehouse was in use when the house was first investigated in preparation for its restoration. The outbuildings which, on the basis of the archaeological evidence, have been restored or reconstructed consist of an outside kitchen, dairy, well and smokehouse.

The Moody House has long been a familiar landmark in the town. It retained much of the atmosphere of age and long usage which gave a colonial character to old Williamsburg. Little is to be gleaned from the records, however, to enable us to establish the sequence of the house ownership. This scarcity of data is due to the destruction of the James City Records during the Civil War.

It is to the archaeological notes and to the internal evidence revealed by the house framing that we turn in order to piece together the architectural history of the property and its buildings. It is clearly evident that the house in its first form and its several supplementary additions and alterations were all built in the eighteenth century. These changes will be listed in this report.

We know nothing of the occupation of Josiah Moody, one-time owner of the property, but he does not appear to have been particularly well-to-do. Moody acquired the property from William Bland in 1794 and it continued in his name until 1820. There are no insurance policies bearing on the property. However, the Ewing lot adjoining at the east side was insured and the Moody property was noted as its westerly boundary.

DATING OF THE HOUSE

The exact dates of the construction of the original house and of its additions cannot be established by documentary evidence. There is, however, an unmistakable basis for establishing these dates in an approximate way. There are known architectural characteristics such as molding contours, the form of fireplaces and chimneys, paint layering and the steepness of roof slopes that we have come to accept as having validity as guides to the period of a house. Also, clues found in the house framing when exposed to view and the evidence of additions made to foundations contribute to the process of untangling the skein of a house history.

It was the conclusion of the archaeologist and architects who studied the old building that the original part of the house was built between the first quarter and the middle of the eighteenth century. It was not possible to determine even an approximate date for the additions.

EVOLUTION OF THE HOUSE PLAN

The Moody House is very interesting from the standpoint of the evolution of its plan. A study made of the existing structure of the house prior to its restoration revealed the fact that the first dwelling built on the present site was of a type unusual in Williamsburg, and, in fact, in Virginia altogether. It was concluded at the time the study was made that the original house was one room in depth, "a story and a half dwelling, 18 feet by 32 feet, with a small entrance hall and a room on each side. In the hall was a very steep ladder stair and back of this was a large central chimney which afforded a fireplace for each room. The second floor plan was substantially the same as the first."*

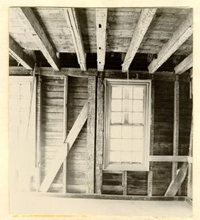

4The above statement was the interpretation made of evidence found in the course of a careful investigation of the old framing of the house. A photograph (reproduced on this page), which was taken at this time of the roof structure over the first landing of the then-existent stairway, shows clearly several features which indicate that a chimney stack had at one time penetrated the roof at this point. In the view shown one is looking upwards in a southwesterly direction at the framing over the south part of the hallway. A horizontal cross member (header) runs from a joist at the top of the picture to another at the right center. The two joists just mentioned define, respectively, the eastern and western limits of the hallway, and the header itself, therefore, is the width of the hallway. The header was placed in this position to receive the joists of the hallway ceiling which were interrupted to provide an opening for the chimney to pass through it.

ROOF FRAMING OVER SOUTH END OF HALL, SHOWING HEADER BEAM AND SAWED-OFF RAFTER ENDS WHICH WERE THE CLUES TO THE ONE-TIME EXISTENCE OF A CHIMNEY AT THIS POINT.

ROOF FRAMING OVER SOUTH END OF HALL, SHOWING HEADER BEAM AND SAWED-OFF RAFTER ENDS WHICH WERE THE CLUES TO THE ONE-TIME EXISTENCE OF A CHIMNEY AT THIS POINT.

Two series of roof rafters are visible in the picture, the steeper members being a part of the original roof framing (when the building was one room deep) and 5 the rafters less steeply inclined (above them in the picture) being the framing erected later to cover the south addition. It will be noted that one of the steeper rafters has been cut off, as has also one of the rafters of lesser slope. Beside each of these rafter "stumps" is another complete rafter which, in the photograph, has been designated as a later member, It seems inconsistent, at first sight, to speak of one of the rafters of the original steep roof as a later rafter, but this is easily explained. The central chimney, whose stack ran through the opening left by the cutting off of the rafters, not only existed from the beginning but it also remained in this position for some time after the addition was made, so that it was necessary to provide for it an opening through the new roof framing as well as the old. When the inside chimney was eliminated and end chimneys were built, the framework of both the new and the old roofs was strengthened by the addition of new, full-length rafters at the sides of the "amputated" ones. Thus later rafters came to exist in the old, original roof framing as well as in the roof framing of the addition.

So, it is evident that the roof framing over the south end of the hallway bore definite evidence of having been penetrated at one time by an aperture which measured in its north-south direction, about 2'-8" and in east-west extent, about 3'-10 ½". The. architects who examined the structure concluded, and rightly, that the hole in the roof could only have been made to permit a chimney stack to rise at this point.

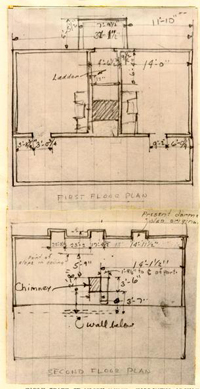

Sketch plans, drawn by the architects who made the measured drawings and field notes of the house before its reconstruction, show what the archaeological 6 investigations indicated as the original first and second floor layouts of the house. A photostatic copy of these plans shows that the house in its first condition, as the quotation given earlier stated, was a one-room-deep house with a single room on either side of a central hallway. The center hall, as is seen, is interrupted toward its south (rear) end by a chimney extending from wall-to-wall. The second floor plan shows a smaller chimney stack located above the position of the chimney below.

EARLY STATE OF MOODY HOUSE, FOLLOWING ARCHAEOLGOCIAL EVIDENCE. THE CHIMENY AT THIS TIME ROSE THROUGH THE CENTER OF THE HOUSE AND THE SECOND FLOOR WAS REACHED BY A LADDER.

EARLY STATE OF MOODY HOUSE, FOLLOWING ARCHAEOLGOCIAL EVIDENCE. THE CHIMENY AT THIS TIME ROSE THROUGH THE CENTER OF THE HOUSE AND THE SECOND FLOOR WAS REACHED BY A LADDER.

It will be noted that a transverse partition wall cuts the entrance vestibule down to a space 7 6'-4" by 4'-6 ½". This was manifestly too small an area to accommodate a normal stair and the architects were of the opinion that the second floor was reached by means of a ladder stair, which was believed to have been located in the southwest angle of the vestibule space (see plan on preceding page).

The structural history of the house does not end with the story of the building of the one-room-deep dwelling. This first house apparently served for a number of years and was then increased in size by the addition of two rooms at the back with a leanto roof over them. As we have already seen, this new half roof was erected above the original steeper roof without disturbing the latter.

At a still later date the house underwent other modifications. It was extended 13 feet towards the west and at the time this addition was made the hall and all of the rooms were enlarged. The central chimney was also removed to permit the hallway to run through the house without interruption, and two new chimneys were built, one at either end of the house. These changes, along with certain other alterations, such as the relocation of some of the window and door openings, completed the modifications which were made to the house in the eighteenth century. The house as reconstructed represents this final phase in the eighteenth-century development of the house.

The successive stages in the enlargement of the house were revealed to the architects by a study of the old framework of the building. The extension of the roof to accommodate the south leanto addition, as has been said, was clearly visible in the roof framing. The fact that the house was extended to the west was equally clearly evident in the wall framing. The accompanying photograph shows part of the north well of the house after it had been stripped for examination. The

8

NORTH WALL OF HOUSE BEFORE ITS RECONSTRUCTION SHOWING THE PAIR OF POSTS WHICH REPRESENT THE MEETING POINT OF THE ORIGINAL WALL WITH THAT OF THE WEST ADDITION.

termination of the old portion of the house wall (at right) and the beginning of the new is clearly evident. The mortise holes in the beam above the original cornerpost show the position of the first west wall of the house. It is apparent from this photograph also that the window shown in it is not in its original location because it would never have been placed so close to the corner of the old house, which would have made bracing of this corner impossible.

NORTH WALL OF HOUSE BEFORE ITS RECONSTRUCTION SHOWING THE PAIR OF POSTS WHICH REPRESENT THE MEETING POINT OF THE ORIGINAL WALL WITH THAT OF THE WEST ADDITION.

termination of the old portion of the house wall (at right) and the beginning of the new is clearly evident. The mortise holes in the beam above the original cornerpost show the position of the first west wall of the house. It is apparent from this photograph also that the window shown in it is not in its original location because it would never have been placed so close to the corner of the old house, which would have made bracing of this corner impossible.

ORIGINAL HOUSE PLAN EXCEPTIONAL IN TYPE

Certain features of the original house plan (see page 3) are notable because they are of comparatively rare occurrence in Virginia. Although it can probably be safely said that end chimneys are typical in eighteenth century Virginia dwellings, nevertheless inside chimneys are by no means infrequently found. Such inside chimneys are sometimes placed so as to parallel the wall of the room in which they are located 9 and they are at other times grouped at the meeting corners of three or more rooms and form corner fireplaces in these rooms. An example of such clustered corner chimneys is found in the west wing of the Randolph-Peachy House in Williamsburg, and the type is found elsewhere in Virginia. Inside chimneys are also mentioned a number of times in the minutes of eighteenth-century parish churches of Virginia.

The interior chimney was, therefore, not rare in the colony but the interior chimney placed between two rooms in what normally is a hallway running without interruption from front to rear of the house is rare. A search through many Virginia house plans has brought to light only one other example (shown here) of such a plan type and this is found not in the house proper but in the two flanking wings of the building. (See neighboring plan of Harewood, Jefferson County, West Virginia [Virginia in colonial times].) This plan type, however, was used frequently in colonial Connecticut, and an example of a Connecticut house plan very similar to the original Moody plan is shown at the left.

HAREWOOD, JEFFERSON COUNTY, WEST VIRGINIA

HAREWOOD, JEFFERSON COUNTY, WEST VIRGINIA

FIRST FLOOR PLAN

FIRST FLOOR PLAN

THOMAS LEE HOUSE

It is of interest to speculate upon the question as to why this house type was not in more widespread use in Virginia. Its frequent use in New England 10 indicates that it was a workable scheme and it seems that it would have been more economical to have built in this fashion, since it enabled a single chimney stack to perform the service rendered by two end chimneys.

One thing immediately becomes apparent about this plan type. The placing of the chimney at the center of the house made it impossible to carry the hallway through the house from front to rear. The central hall plan with the passageway bisecting the house was very highly thought of in Virginia and it is found almost without exception in eighteenth century house plans in the Old Dominion. This feature (the central hallway) served a very important function in the sultry climate of Tidewater Virginia because it made possible the opening up of the building from one side to another and the ventilating of the rooms. The practicality, and, for that matter, the pleasantness and beauty of the uninterrupted central hallway probably lead to the predominance of the center-hall-end-chimney house type over the center-chimney type. The former type, of course, also had the advantage over the center-chimney plan in that it was, in the days before the invention of the clay flue lining, more fire-safe than the latter type. That the consideration of fire safety was not of itself a sufficient reason to explain the failure of the center-chimney plan to spread more widely than it did is indicated by the fact brought out above that many Virginia houses did have interior chimneys of one sort or another.

THE LADDER STAIR OF THE ORIGINAL HOUSE

The other unusual feature mentioned in the foregoing discussion of the plan - the ladder stair - was probably, in this case, a direct result of the constriction of the hall area. Although, as the Connecticut plan bears witness, this plan type 11 did not render the use of a normal stair impossible, in the case of the original Moody House it would have been difficult, probably, to have used it. Furthermore such ladder stairs were doubtless in frequent use in the earlier dwellings of the colony. That they persisted in use until after the middle of the eighteenth century may be surmised from sketch plans of the Brick House Tavern in Williamsburg which accompany the deed for the property given by Dr. William Carter to Hugh Walker in 1764. (See architectural report on the Brick House Tavern.) The plan shows the building to have had two floors which were divided up into six two-story apartments. Though the plans do not indicate how a dweller in one of these duplexes went from one floor of his apartment to the other it is reasonable to suppose, in view of the limited space in the rooms, that this would have been by means of a ladder rather than a stairway. A series of outside stairways at the rear of the building, let us say, hardly seems feasible.

If the use of the ladder stair in the apartments of the original Brick House Tavern still falls in the realm of conjecture, a plan made sometime during the first half of the eighteenth century makes a certainty of it. This plan, found among the papers of John Custis, who died in 1749 in Williamsburg, is the first floor layout of a multiple dwelling for four families. The building was to have been square and divided on the first floor and presumably on the second into four equal rooms, each pair of rooms to be occupied by a family. Four corner fireplaces are grouped together at the center and a step ladder is shown on the plan beside the entrance door of the ground floor room, the ladder providing the means of ascent to the upper room of the two-room duplex apartment.*

THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE HOUSE

The reconstruction of the Moody House conformed to the practice followed by Colonial Williamsburg in the rebuilding of structures other than exhibition buildings; that is to say, the exterior was returned with fidelity to its eighteenth-century condition, as careful research and archaeological investigation revealed this. Internally, however, the building was designed for present-day use and consequently its plan departed from the eighteenth-century layout. Kenneth Chorley, at this time, made a clear statement of the Colonial Williamsburg policy respecting the treatment of building exteriors and interiors in a letter to A. Edwin Kendrew, dated May 10, 1939 (General Files): "I have the feeling that the policy that we should adopt is to carry out an exterior restoration of these buildings, going to no end to have the exterior authentic, but when it comes to the Interior arrangement (and by arrangement, I mean partitions, size of rooms, etc.) I think we must feel perfectly free to work out the best possible living arrangements. That is, if we are restoring the buildings as residences, then the interior arrangements should be the best possible arrangements for guest houses; if, as taverns, then the best possible arrangement for taverns. In other words, we should have no hesitancy in disregarding any evidence in so far as the interior arrangements go." [Moody House Folder]

The interior, in this case, was planned specifically for use as an adjunct to the Williamsburg Inn, for the accommodation of those who might desire to live for a time in the atmosphere of an early colonial house in a village setting. The house as first rebuilt by Colonial Williamsburg had five bedrooms and five baths together with a common living room. It was so arranged as to permit several rooms to be used in combination as a suite for a party of guests or, on the other hand to allow the rooms and baths to be used individually. The building was operated in this fashion for almost ten years but it has now been altered to make it suitable for use as a

13

PRESENT CONDITION of MOODY HOUSE

PRESENT CONDITION of MOODY HOUSE

Williamsburg, Virginia

March 6, 1950

one-family dwelling. The original kitchen was reconstructed, its plan also being arranged for use as a guest house or as a house for servants.

It has been noted that the old Moody House, including its foundation brickwork, was razed and reconstructed instead of being restored. As the photograph shown on page 19 of the site at the beginning of the reconstruction of the structure indicates, only the chimneys up to the beginning of the final shafts were left in place.

14In short, the procedure followed in the case of this house was that which would have been necessary if the building had been so decrepit as to make its repair infeasible. This was apparently not the case, however, if we are to judge by the extant records concerning the condition of the old house and photographs made of its framework at the time it was being demolished. Two of these photographs are shown in this report (PP. 4 and 8). These seem to indicate that the framing, considering its age, was in good condition. That much of the exterior woodwork was fit for retention follows from the findings made by Singleton P. Moorehead who examined it in 1929. A transcript of Mr. Moorehead's report is given on p.44. Though the building doubtless deteriorated some in the decade between the writing of this report and the time when active measures were undertaken for its rehabilitation, nevertheless this deterioration could not have been extensive.

That the house merited scrupulous restoration appears from statements made in 1929, when its reconditioning was first seriously being considered, by persons whose opinions command respect. Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin, for example, in a letter written on May 18, 1929 to Colonel Arthur Woods speaks of it as follows: "The Lee House which is #31 in Block II is from every point of view one of the most charming Colonial houses in Williamsburg." Walter M. Macomber, resident architect in Williamsburg, representing Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, the architects in charge of the work, says, in a letter concerning the house written to Kenneth Chorley on May 24 of the same year, that "There are not very many old Colonial buildings in Williamsburg outside of 'Area A' that 15 are worth much more than exterior restoration, but undoubtedly a building of the Lee House type is worth doing well inside and out . . . I am enclosing two rough sketches" he continues, "showing the possible changes it seems rather too bad, when it would be such a simple matter to make the house more livable, and especially when it is such a fine building to begin with, these changes are not made."

The remarks made here should not be taken, in any sense, as a criticism of the painstaking and accurate manner in which the house was reconstructed. But the preservation of an old house, in the opinion of the writers of this report, is always to be preferred to its demolition and reconstruction. Very much of great value is lost in the latter process. The writers have no doubt, in view of the careful manner in which the Brush-Everard, Tayloe and other old houses are at present being restored, that were the old Moody House today to be reconditioned, it, too would be restored and in such a manner that every usable old element of the structure and the exterior would be preserved.

It will be seen that the opinion expressed above conforms to certain statements of principle made by the Committee of Advisory Architects in its code of restoration principles and procedure set up in 1928. The following statements are quoted from the code:

5. No surviving old work should be rebuilt for structural reasons if any reasonable additional trouble and expense would suffice to preserve it.16

6. There should be held in the minds of the architects in the treatment of buildings the distinction between Preservation where the object is scrupulous retention of the surviving work by ordinary repair, and Restoration where the object is the recovery of the old form by new work; the largest practicable number of buildings should be preserved rather than restored.

In amplification of these briefly-stated principles, some opinions of eminent architect-restorers on the subject of the preservation of old buildings are given in the Architectural Report, Approved Methods of Restoration at Colonial Williamsburg, which may be consulted in the Architectural Department.

NOTES ON THE EXTERIOR

EXTERNAL MEASUREMENTS.

The house measures 45'-3" in length and 28'-3 ½" in depth. The above measurements are those of the (reconstructed) original portion of the house plus its eighteenth-century rear extension and the addition to the west.

ROOF TYPE.

The original house had an A roof. When, later in the eighteenth century, the addition, 10'-2" in depth, was made on the south side, a new roof of lesser slope was built above the south half of the old roof and continued downward without a break to cover the extension. The house, with its shorter front slope and longer rear slope thus came to resemble a New England "salt box" house (see frontispiece).

DORMERS.

There are, all told, seven dormers, four on the front (north) roof slope and three on the rear (south) slope. The north dormers are centered over the three windows and doorway of the first floor. Of the south dormers, the middle one is centered on the rear doorway while the other two have no regular relationship to the windows below.

The dormers of the front elevation are of the gable-ended type while the rear dormers are hipped. The sides of all the dormers, 17 and the "pediments" of the gable-ended dormers are faced with flush, random-width boards. The facing boards of the side dormer follow the inclines of the respective roof slopes on which the dormers are located.

All of the dormers are in the positions of the dormers found in place, which may have been of colonial origin, with the exception of the rear center dormer which did not exist on the old Roper-Lee House. The latter dormer was added to bring light to the upper part of the stair hall.

The dormers, in common with the other features of the exterior of the house, are reconstructed. Their framing is new as is a large part of their exterior facing and trim. The architects did, however, strive to salvage and reuse as much of the outside woodwork of the dormers as possible.

BRICKWORK.

The brickwork used on the exterior of the Moody House consists of the following: 1) the foundations, both of the house proper and of the front porch and basement bulkhead; 2) the rear platform and steps; 3) the two end chimneys and the leanto chimney, and 4) the brick ground-level gutters along the north and south sides of the house. All of the brickwork exposed on the exterior of the house is either old brickwork left in place or composed of salvaged eighteenth-century brick.

Foundations.

The foundation brickwork of the house itself and of the front porch and bulkhead is made of reused old brick. The brick are laid in oyster shell lime mortar with tooled joints. The brick color varies and brick of a deep red, salmon color and purplish red are in evidence. A considerable amount of partial glazing is present and the general cast of the foundation walls is of a purplish gray.

18The brick dimensions measured on the site are as follows:

| Length: | From 8 ¼" to 8 ½". |

| Width: | From 3 ¾" to 4 3/8" |

| Thickness: | From 2 ¾" to 2 7/8" |

There are, among the brick in the walls, as is always the case with old brickwork, a few brick which fall outside these dimension ranges.

Rear Platform.

The existence in colonial times of a rear brick entrance platform became evident when the late wood porch which spanned the back was removed. The photo below is a view of the rear (south) elevation of the house after the porch was torn down. In front of the doorway may be seen the foundation of an old brick stoop which had remained hidden under the floor of the "modern" porch. On the basis of this foundation, a brick platform and two brick steps were built on the site of this foundation. Except for the fact that the customary wood nosings are not present (the old foundation bore no evidence of them) the stoop is of a type frequently found on colonial Virginia houses. The front and rear platforms and steps of the Wythe House are examples of this

REAR VIEW OF OLD ROPER-LEE HOUSE SHOWING BRICK STOOP FOUNDATION DISCOVERED AFTER REMOVAL OF LATE PORCH.

19

type of entrance stoop. In the reconstruction of the platform and steps old salvaged bricks were used for all visible work.

REAR VIEW OF OLD ROPER-LEE HOUSE SHOWING BRICK STOOP FOUNDATION DISCOVERED AFTER REMOVAL OF LATE PORCH.

19

type of entrance stoop. In the reconstruction of the platform and steps old salvaged bricks were used for all visible work.

Chimneys.

The two end chimneys, are in large part old with the brickwork, except for repointing, left as it was found. The illustration shown at the left shows the condition of the chimneys after the house had been razed and its reconstruction commenced. Only the upper shafts, and the caps were removed. These were rebuilt with old brick in the exact form in which they had existed previously. These shafts are, by the way, T-shaped in section.

PHOTOGRAPH SHOWING MOODY HOUSE IN PROCESS OF RECONSTRUCTION. THE PORTIONS OF THE TWO END CHIMNEYS SHOWN WERE LEFT UNDISTURBED.

PHOTOGRAPH SHOWING MOODY HOUSE IN PROCESS OF RECONSTRUCTION. THE PORTIONS OF THE TWO END CHIMNEYS SHOWN WERE LEFT UNDISTURBED.

An interesting feature of these chimneys and one which is not too common, is the flat "panel" of brick, about 1'-0" in width, which is placed in the house wall at either side of the chimney. This extends from the slope of the first haunch approximately to the second floor level.

The chimney which serves the fireplace at the west end of the south addition was in bad repair and required rebuilding. Old brick was used in this process and the form of the existing chimney was followed. The shaft of this chimney, which 20 serves a single flue, is rectangular in section.

The color of the old undisturbed brickwork of the end chimneys is slightly different from that of the foundations. Bricks of a salmon pink, deep red and reddish purple predominate and some evidence of glazing is found. The brick of the reconstructed parts of these chimneys and of the reconstructed leanto chimney has more of the salmon brick, giving these reconstructed members a somewhat lighter cast than the brickwork of the bodies of the end chimneys.

The brick of the undisturbed parts of the end chimneys was measured on the site and found to have the following dimensions:

| Length: | From 8 ¼" to 8 ¾" |

| Width: | From 3 7/8" to 4 ¼" |

| Thickness: | From 2 3/8" to 2 7/8" |

All chimney brickwork is laid in oyster shell lime mortar with tooled joints. The height of six brick courses, measured from center to center of joints, varied from point to point on the chimney faces from 17 ½" to 18".

Ground-level Gutters.

Brick ground level gutters, were placed, adjacent to the house, along the entire length of the north and south fronts, except where the porches intervened to interrupt them. Such gutters were in common use in colonial times in lieu of hung gutters, although the latter were also sometimes used. Fragments of old brick gutters were found along the foundation of the street front of the Barraud House directly opposite the Moody House on Francis Street and these served as the model for the gutters of the Moody House. Old brick were used in the construction of these gutters.

EXTERIOR WALLS.

The weatherboarding on the four faces of the house is of the beaded type similar to that which was found on the north front of the old house. The square-edged window sills are likewise beaded and the sill beads line up with the beaded edges of those weatherboards whose bottoms are on a level with the lower edges of the sills.

EXTERIOR TRIM.

The weatherboarding is stopped at the four corners of the house by corner boards, the broad sides of which face north or south, as the case may be, and whose edges appear on the two ends of the house. Their outside edges have been given the bead that is customarily found on the exposed outside edges of all trim in eighteenth century work.

The front cornice is new, but it is patterned after the old colonial cornice which remained in place at the time the work on the house began. This cornice, with its crown mold, fascia, flat modillionless soffit and bed mold follows a typical eighteenth century pattern, and many similar cornices have been found on old buildings of Williamsburg and the vicinity.

The rather considerable projection of eighteen-century cornices made necessary some treatment of the ends which would conceal the "raw" cornice profile which, without this, would be visible when the house was viewed from the ends, because it was not practicable to continue the relatively bulky member up the gable ends of the house. Two devices, in general, were employed to accomplish this. Sometimes the cornice at its ends was returned against a flat board which paralleled the direction of the cornice itself. Much more frequently it was continued to the ends of the building and stopped by flat boards perpendicular to the face of 22 the building on which the cornice was found. The outside edges of these boards, known as cornice end boards, followed the cornice profile either exactly or in a general way only. The latter solution, the use of cornice end boards, was the one adopted here. The profiles of these cornice end boards varied greatly so that it is difficult to find an old example of which this one is an exact copy. The present one, however, resembles in character, if not in exact contour, the old cornice end board which exists at the southwest corner of the Travis House in Williamsburg.

The rear cornice of the house, following the usage in Williamsburg houses of the colonial period, is much less pretentious than the front one. In actuality it merely repeats the crown mold of the front cornice, with its cyma recta above a cyma reversa.

On the gable ends of the house the transition between the roofing and the weatherboarding is effected in the customary colonial manner by the use of barge boards which follow the rakes of the roof and diminish somewhat in the direction of the roof ridge. These are flat boards, the lower sides of which are beaded. The barge boards which run along the front slope overlap the cornice end boards and terminate in a reverse curve, while those following the lesser rear slope are cut at their lower ends to the shape of the rear cornice (crown mold) and receive this.

FRONT PORCH AND REAR PLATFORM

Front Porch.

The nineteenth century Greek revival porch which existed on the house when its reconstruction began was removed since it was an anachronism. In its place a simple unroofed wood platform or stoop, approached from the front by two wood steps, was built, foundation 23 evidence for which was discovered beneath the "Greek" porch. This is supported on a foundation made of old bricks. The platform is equipped with a handrailing, supported by four newel posts which are square in section with rounded tops and two of which are applied to the front wall. The hand-rail, with a finger-grip on one side only, follows very closely the design of an old handrail which still exists in the west gallery of Bruton Church. The simple board intermediate member of this railing, double-beaded top and bottom, is similar to old railing members of the Travis House stairway and of the old stairway found in the Lee House. The bottom rail, a rectangular piece with a top triangular in section, is a commonly-used colonial detail.

PART OF FRONT FACE OF HOUSE SHOWING FOUNDATIONS UNCOVERED WHEN GREEK REVIVAL PORCH WAS REMOVED.

PART OF FRONT FACE OF HOUSE SHOWING FOUNDATIONS UNCOVERED WHEN GREEK REVIVAL PORCH WAS REMOVED.

As was stated above, the present porch was based upon foundation evidence discovered when the Greek revival porch was removed. The photo at the right shows the foundations which were thus uncovered and there are indications that three, rather than two, porches had previously existed on this site. The foundation in the foreground is the remains of a colonial porch. It is reasonable to suppose that this was the porch which existed prior to the removal of the central chimney and the westward extension of the house. In the course of the substitution of the two 24 end chimneys for the center one and the enlargement of the house toward the west, the position of the hallway, doubtless, was also changed by moving it westward to give it a more central location in the enlarged house. This necessitated moving the doorway westward to the position shown in the photograph. The porch was likewise of necessity moved, and the foundations which in the picture center on the doorway represent, in position at least, those of the second colonial porch (the concrete steps at the right are modern). The "Greek" porch was also centered on the doorway but it extended beyond this second foundation to the right and left (the marks are shown on the weatherboarding). Since it was decided to reconstruct the house to its later colonial state, the hallway, door and porch were left in the positions in which they were found.

Rear Platform.

This is a replacement of a late covered leanto porch with columns which extended across most of the rear facade of the building. When this porch was removed the remains of an old brick stoop were found which formed the basis for the present platform and steps (see discussion and photograph under Brickwork).

BULKHEAD.

The bulkhead found in place just south of the chimney on the west front of the building when the work on the house began was of the upright type with a leanto roof. This was late so that it was replaced by one designed on eighteenth century models. This is of the inclined type with two doors which swing on strap hinges. The triangular sides of this bulkhead are faced with random-width beaded shiplap sheathing applied horizontally. The transition between the inclined "roof" or covering of the bulkhead and the sides is effected by means of a rakeboard with an applied cyma reversa (ogee) molding. The 25 brickwork of the foundation is of salvaged colonial brick. The general design of the bulkhead follows that of the old bulkhead of the Taliaferro-Cole Shop.

WINDOWS.

Some of the windows and trim in the reconstructed house are old members found in the Roper-Lee House and reused. The majority of the windows are new, however, but they are all, in their design, based on old details found in the house. The window sash which remained in place in the Roper-Lee House was partly old and partly modern. The windows and frames of the three front windows and of the window at the north end of the west side were original or at least old. All of the remaining sash were new but a few miscellaneous trim and frame parts through the house were old.

Dormer Windows.

The four front dormer windows have sash three lights wide and four high. The glass size is 7 9/16" x 11 9/16". The sash size was derived from the modern sash found in place but the division in width was changed from two lights to three.

The three rear dormer sash are also three lights wide and four high but due to a difference in glass size (it is, in this case, 8 ½" x 9 15/16") the rear dormer windows are much "squatter" in appearance. Their sash and light sizes are based upon the sizes of the two dormers and their sash which were found in place. As was stated earlier the middle dormer did not exist in the Roper-Lee House.

First Floor Windows.

The three windows of the south (front) facade, the window at the north corner of the east facade and the two windows flanking the chimney on the west facade are the same type -- three lights wide and six high. The glass size is 9 ¼" x 10 11/16". As was remarked 26 above the sash and trim of four of these windows -- the three windows on the street face and the one north of the chimney on the west side, were old. These were reused in the reconstructed house. New sash and trim were installed in the other windows of this type, but these were designed in imitation of the old windows. One of the above windows -- the window on the south side of the chimney on the west elevation -- is a new window altogether. It was installed after the removal of the upright basement bulkhead to bring additional light into the living room.

The other first floor windows, seven in number, are of one type - two lights wide and four high. The glass size is 9" x 10 ½". Six of these are located in the south facade, three on either side of the rear doorway. The seventh is found in the east closet leanto. These windows are all, in the size of their openings, at least, modelled after a single old opening found just east of the rear doorway on the south side of the house. The remaining, considerably larger rear windows were modern.

Since the closet leanto mentioned above has not hitherto been alluded to in this report, it merits a moment's attention. Before the reconstruction of the house a door to the exterior existed in the wall about two feet south of the south side of the chimney. This gave out upon a wood stoop the steps of which lead toward the rear of the house. The porch was late but indications of an old porch were found in the brickwork of the chimney. This porch was not reconstructed, but in its stead, a closet, needed in the adjoining dining room, was built at this point in the form of a leanto with a shed roof. This is lighted by one of the small windows discussed above.

Gable Windows.

A single gable window, two lights wide by four high, was found in the Roper-Lee House in the east side a foot or two south of the chimney. Although the sash and frame of this window were modern, the window set the size and number of divisions for the two gable windows which are now found in the house. One of these is located in the east gable at the point where the window just described existed, while the other, in a corresponding position in the west gable end, is a new window altogether, which was installed to bring additional light to the west bedroom of the second story.

Basement Window Openings.

There are, in all, five basement window openings, three located in the brick wall directly beneath the three windows of the front facade and one in the basement wall of each of the two sides. The latter two openings are in each case just north of the north face of the chimney but they do not line up with the first floor windows above.

The basement windows openings are in the locations of old openings which existed when the reconstruction of the house was started. Four of these existing openings were equipped with wooden grilles which were late in design and there was evidence that the original openings had extended two brick courses lower but had been reduced in height by bricking up. In the reconstruction of the openings they were returned to the original height and new grilles designed after the manner of many colonial basement grilles found in Williamsburg were installed. These have molded frames divided in the center by a post, and square-cut sills, set flush with the brickwork of the walls. The grilles consist in three wood bars, square in section, which run between the frame and the center post. The bars are set horizontally and turned so as to present an edge 28 front and rear. In colonial times this completed the window equipment; the basement windows, thus, were openings only, protected by a grille so that the air could circulate freely beneath the building, a desirable feature in the sultry climate of Virginia. We today require closed basements, however, so that in the Moody House, as elsewhere in the restored and reconstructed buildings of Williamsburg, modern stock basement windows were installed back of the grilles.

SHUTTERS.

The shutters used on the first floor windows of the house are of the panelled type and all of them are reproductions. When the work on the house began nine shutters were found on the house. Six of these were on the three windows of the street facade and they were of the louvered type. The remaining three blinds were on the side windows two on the 18-light window of the east facade and one on the corresponding window of the west front. The three latter shutters were old panelled shutters, the design of which consisted of two equal rectangular panels placed one above and one below a square panel. Although these old shutters were not reused they formed the basis for the design of the new shutters which were hung on the reconstructed house.

The three front windows and the two northernmost side windows, being of the same size, received the same type of shutter -- a reproduction of the old shutters found on the side windows. The six 8-light windows of the rear facade and their companion of the closet leanto were too narrow to warrant the use of two shutters, so that they were each equipped with a single two-panelled shutter.

The shutters are hung on H-L hinges, reproduced after the design of the old H-L hinges which were in common use on shutters in Virginia in the eighteenth 29 century. Several of these old hinges were found on the shutters of the Roper-Lee House.

DOORS.

The doors of the house are, for the most part, two-, four- and six-panel doors, most of which are reproductions, the design being based on that of old doors found in the house and of colonial Virginia doors generally. A few board-and-batten doors have been used in the house, mostly on the second floor and in the basement. All of these are new doors.

Of the few old doors reused in the reconstructed house it may be well to mention the two doors leading from the first floor hallway to the dining (east front) room and the living (west front) room respectively. The architraves (trim and frame) of these doors existed in the Roper-Lee House and though they were not original they were repaired and reused, since they were of colonial character. Except for the interior trim of the front door these were the only architraves now in the house which formerly existed in the Roper-Lee House, the remainder of the present ones being new. These architraves are of the double-molded type, the type which, with the single-molded variety used on doors in less-prominent locations, is used, for the most part, throughout the entire house. Double- and single-molded trim is also used, by the way, on the windows of the house, including the basement and dormer windows.

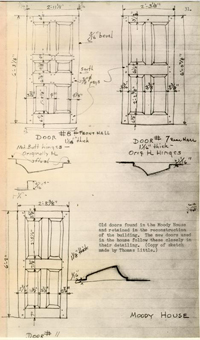

For further information on the doors of the house, the reader may consult the door schedule, sheet #5 of the working drawings. The window schedule is on sheet #200. (Since these sheets were drawn up before the 1950 modification of the house interior these schedules are subject to some revision.) The page which follows 30 this is a photostat of a free-hand drawing of three old doors measured on the site before the Roper-Lee House was demolished.

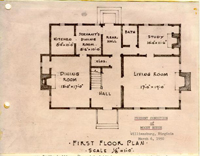

INTERIOR OF THE HOUSE

As we have noted on page 12, the interior of the Moody House was first reconstructed specifically for "use as an adjunct to the Williamsburg Inn, for the accommodation of those who might desire to live for a time in the atmosphere of an early colonial house in a village setting." The house at that time (1939) had five bedrooms and five baths, together with one common living room. Later, in 1950, the house interior was restudied and rearranged so as to meet the requirements of a single family. The plan of the house after these changes were made is shown on page 13 of this report. It is an arrangement which places the principal living features of the first floor, (living and dining rooms and stair hall) within the front rectangle of the house, while varied services are placed at the rear, within the leanto. A "study" that serves as an addition to the living room area is also in the rear part of the house.

Because of the necessity for flexibility the interiors of Colonial Williamsburg houses are designed so as to be adjustable to various changing needs. As Mr. Chorley said in his letter of May 10, 1939, within the exterior enclosure of the house, "we must feel perfectly free to work out the best possible living arrangements. That is, if we are restoring the buildings as residences, then the interior arrangements should be the best possible arrangements" for present-day residential uses.

Within the house there are ample evidences of the original Moody House, even though its parts were disassembled and then reconstructed.

31

Old doors found in the Moody House and retained in the reconstruction of the building. The new doors used in the house follow these closely in their detailing. (Copy of sketch made by Thomas Little.)

32

Many elements of the joinery, architectural features such as the stairway, fireplaces, floors, etc. are from the original house and here form a part of the new interior. The color scheme, discussed in detail elsewhere in this report, is a slight modification of those colors discovered in the house which were believed to go back to colonial times.

Old doors found in the Moody House and retained in the reconstruction of the building. The new doors used in the house follow these closely in their detailing. (Copy of sketch made by Thomas Little.)

32

Many elements of the joinery, architectural features such as the stairway, fireplaces, floors, etc. are from the original house and here form a part of the new interior. The color scheme, discussed in detail elsewhere in this report, is a slight modification of those colors discovered in the house which were believed to go back to colonial times.

The Stairway deserves more than passing mention, partly because, in its arrangement and details, it is a typical colonial Williamsburg stair. It is what is termed "dog-legged," meaning that the steps run upwards to a landing and then continue with further risers to the second floor. In dismantling the wood structure of the house, prior to its reconstruction, the utmost care was taken in removing the stairway from the building and in storing it for reuse. No parts of the stairway, except the framing, were discarded. Some minor repairs were, indeed, made to moldings and balusters. Since the nosings had been worn down by long use, they were renewed by setting new nosings into the original treads.

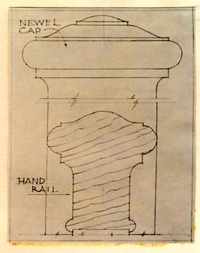

The newel posts are approximately four inches square and have a simple molded top. The handrail is fairly broad and deep. A detail of this, given on the following page, shows the skillful manner in which the same moldings are used on both the handrail and the newel cap. Furthermore, the moldings of the chair railing used throughout the first floor repeat the torus-type molding of the handrailing and cap.

The stair has what is termed a "closed stringer" meaning that the step ends are concealed behind a molded board that follows the slope of the handrail. There are three turned balusters to each step. These are unusually handsome and they are of a type which is characteristic of stairways of the Virginia locality. The Mayo House in Williamsburg, now 33 demolished, had an eighteenth century stairway with balusters of an almost identical profile. The balusters of the Taliaferro-Cole stair are also similar. It is suggested that the Taliaferro-Cole architectural report be examined to compare the stairway details with those of the Moody House. See also working drawing sheet #104 and the sketch on the next page for further information on the Moody stair.

MANTELS.

These, with one exception, were found in the Moody house and are old. Some of them may be original and of the eighteenth century. There are evidences that some of the mantels were tampered with, possibly in the nineteenth century. As an example, the heavy unmolded shelf in the southwest room (study) is apparently an addition. Its scarred surface, indicating age and use, was justification for its having been retained. A new mantel shelf, even though it were correct in profile, would lose a certain quality that this authentically old example possesses.

Both the living and dining room mantels are old and of the house. They are simple in their design and appropriate to a Williamsburg house of moderate size.

The two second floor bedroom mantels are alike in their design. The one in the east room is original, and is from the old Moody House. The

34

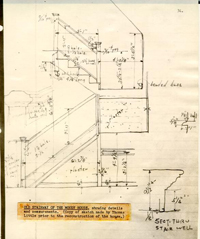

OLD STAIRWAY OF THE MOODY HOUSE, showing details and measurements. (Copy of sketch made by Thomas Little prior to the reconstruction of the house.)

35

mantel of the west room is new, a copy of the mantel in the east room.

OLD STAIRWAY OF THE MOODY HOUSE, showing details and measurements. (Copy of sketch made by Thomas Little prior to the reconstruction of the house.)

35

mantel of the west room is new, a copy of the mantel in the east room.

CHAIR RAILINGS.

Chair railings are found only on the first floor, and these are modeled after the original chair railing found in the old house. Since there was not enough of this old railing for all of the rooms in which a chair railing was to be used, this original railing was pieced out by new moldings of the same profiles.

FLOORS.

These are all of old flooring boards, partly salvaged from the house and reused. A small portion of the flooring consists of old floor boards from other old houses. Floor board widths vary from 4 ½" to 7 ¼".

CORNICE.

The only room in the house having a cornice is the living (west) room and this follows the typical cornice shape found in other colonial houses of the locality.

The working drawings prepared by the Architectural Department of Colonial Williamsburg, especially sheets #101, 102, 104 and 105, should be examined in order to gain a fuller understanding of the treatment accorded the hearths, wardrobes, doors, window trim, etc.

HALLWAY OF OLD HOUSE LOOKING NORTH. PART OF ORIGINAL STAIRRAIL IS VISIBLE AS WELL AS SOFFITS OF SECOND FLIGHT AND PLATFORM OF STAIR.

HALLWAY OF OLD HOUSE LOOKING NORTH. PART OF ORIGINAL STAIRRAIL IS VISIBLE AS WELL AS SOFFITS OF SECOND FLIGHT AND PLATFORM OF STAIR.

COLOR NOTES

More old color was found on the woodwork of the Moody House than is usual with old houses and the nature of these colors was surprisingly interesting. The following is a record, made at the time the paintwork was examined, which lists the old colors which were chosen for reuse in the reconstructed house:

First Floor

Northeast Room: the first [lowest layer of] green and the first ye1low as exposed on the chair rail on the north side of the room.

Hall: the blue as exposed on the stair balusters; the brown color as exposed on the door from the northeast room, on the baseboard rail in the northwest room or any of the several similar places since this color was used generally at many points throughout the building.

Northwest Room: first yellow as exposed on the trim of the west window and the east chair rail.

Southwest Room: the first green and the first yellow as exposed on the north chair rail and the west cupboard door.

Second Floor

West Room: pink exposed on window stool.

East Room: blue as exposed on north window stool.

On the first floor there are several examples of a modified marbleizing, chiefly on the doors in the northwest and southwest rooms. Panels have been cleaned in each of these rooms, though it was not felt necessary to make samples for record.

"Mr. Thrall [the painter] proceeded with this work ... with an attempt made to keep the above mentioned pieces of the trim which would hold colors exposed for future reference. Mantels throughout the building seemed to be black. No samples were made of the mantels, as in the 37 case of the marbelized doors, since it was felt that the color could be matched at any time." (These notes were recorded by Singleton P. Moorehead, August 22, 1939. Mrs. Nash prepared the paint schedule as of August 16, 1939.)

It is apparent that saving of color patches was found to be impractical but matched colors were made for the paint shop records. There was, however, one exception; the marbleized paint on the inside face of the door of the north closet of the southwest room was preserved as a record for future use, the old door itself being reused in the reconstructed house.

EXTERIOR AND INTERIOR PAINT COLORS

The painted surface colors used in the Moody House after its reconstruction in 1939 were based upon the original ones revealed by the investigation and scraping of wood and wall surfaces within the house and on its exterior. The inside door face of the north closet in the southwest room, ground floor, shows original graining. The adjoining closet was grained in 1939 to match the original. The room designations used below refer to the house plan as it was before the interior was partially remodeled in 1950. Working drawings #3 and #4 (July 14, 1939) show these plans.

| Color No. | Finish | Location | Color Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 387 | Japan | Woodwork, lst fl., S.W. room, graining over trim #379. | Pale tan-green |

| 397 | Satin | Woodwork, 1st fl. S.W. room and S.W. bath. | Yellow-tan (warm) |

| 38 | |||

| 380 | Satin | Woodwork, 2nd fl. W. Bedroom | Gray-green |

| 382 | Satin | Woodwork, 2nd fl. E. Bedroom and N.E. bath. | Strawberry-tan (Faded rose) |

| 371 | Satin | Woodwork, lst fl. N E, room, excepting doors. S.E. room, excepting doors &, S.E. Bath, excepting doors. Fireplace facing of Living Room. | Sage-green-gray |

| 375 | Satin | Woodwork, Baseboards and fireplace facings in all rooms, excepting N.E. Room. Woodwork, stair hand rail, newels and stringers. Woodwork, all interior doors, except closet doors of N.W. | Reddish-Brown, dark |

| 175 | Masury's "Nomar" Flat Black | Woodwork, stair risers, mantels in all rooms. | Flat Black |

| 376 | Satin Finish | Woodwork, Halls | Blue-gray (slight mauve cast) |

| 377 | Satin Finish | Woodwork, 1st Fl., N.W. room and N.W. bath | White-cream |

| 381 | Satin Finish | Walls, 1st Fl., S.E. Bath. | Light gray-green |

| 701 | Masury's Satin | Walls, 1st Fl., N.W. Bath, & S.W. Bath. 2nd Fl., N.E. Bath | White |

| 800 | Benj. Moore's Dulopake | Walls, all rooms excepting Baths | Flat White |

| Color No. | Finish | Location | Color Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | Masury's Deck Paint | Exterior door, sills, stair treads. | Cafe au lait (Brown tan) |

| 331 | White Lead | Woodwork, exterior doors, shutters, and bulkhead doors. | White with slight trace of umber. |

| 696 | White Lead | Woodwork, exterior body of house and trim | White with slight green cast. |

PAINT COLORS (EXTERIOR AND INTERIOR) AS REVISED, JULY 7, 1950

The exterior colors, and some of the interior colors, are reproductions of the old colors as used in the original reconstruction of the house. Some of the colors, on the other hand, do not represent the old colors.

EXTERIOR PAINT COLORS

These repeat the colors of the 1939 reconstruction, as recommended by the architects, except that the shutter color was changed from white to a dark green color.

INTERIOR PAINT COLORS

Venetian Blinds. These are painted an off white with a light tint of the woodwork color, satin finish.

The first floor room designations used below are those found on the plan drawing, p. 13. The room titles in parentheses are those used before the 1950 remodeling and are the ones found in the preceding color listing.

| Color No. | Finish | Location | Color Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 371 | Satin | Woodwork | Gray-green |

| 371 | Satin | Doors | Gray-green |

| Dull finish, rubbed | Stair Handrail, natural pine, stained and rubbed | Natural wood | |

| 40 | |||

| 371 | Satin | Newel Posts, painted same as woodwork.* | Sage-Green, grayed. |

| Satin | Stair treads, pine, stained and rubbed. | Natural | |

| Satin | Risers, stained and rubbed. | Natural | |

| Flat | Walls, plaster | White with light tint of #371 | |

| Flat | Ceiling | White | |

| Color No. | Finish | Location | Color Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIVING ROOM (N.W. ROOM) | |||

| 379 | Satin Finish | Baseboards | Buff |

| 379 | Satin Finish | Doors | Buff |

| 379 | Satin Finish | Chimneypiece | Buff |

| 379 | Satin Finish | Other woodwork | Buff |

| Flat | Ceiling, plaster | White | |

| Flat | Walls, plaster | White with light tint of #379 | |

| Flat | Fireplace facing (Surround) | Black | |

| DINING ROOM (N.E. ROOM) | |||

| 371 | Satin | Baseboards | Gray-green |

| 371 | Satin | Doors | Gray-green |

| 371 | Satin | Chimneypiece | Gray-green |

| 41 | |||

| 371 | Satin | Other woodwork | Gray-green |

| Black | Flat | Fireplace facing | Black |

| Flat | Walls, plaster | White with slight tint, of 371 | |

| Flat | Ceiling | White | |

| SERVANT'S DINING ROOM (S.E ROOM) | |||

| 371 | Satin | Baseboards | Gray-green |

| 371 | Satin | Doors | Gray-green |

| 371 | Satin | Other woodwork | Gray-green |

| White | Flat | Walls, plaster | White with slight tint of 371 |

| White | Flat | Ceiling | White |

| KITCHEN (S.E. BATH) | |||

| 103 | Satin | Baseboard | Black |

| 103 | Satin | Doors | Ivory |

| 103 | Satin | Other woodwork, including kitchen cabinets. | Ivory |

| Satin | Ceiling | White | |

| STUDY (S.W. ROOM) | |||

| 287 | Satin | Baseboard | Light buff |

| 287 | Satin | Doors | Light buff |

| 287 | Satin | Chimneypiece | Light buff |

| 287 | Satin | Other woodwork | Light buff |

| 42 | |||

| Flat | Fireplace facing | Black | |

| Flat | Walls, plaster | Off-White | |

| Flat | Ceiling | White | |

| BATHROOM OFF STUDY (S.W. BATH) | |||

| 371 | Satin | Baseboards | Black |

| Satin | Doors | White with light tint of 371 | |

| 371 | Satin | Other woodwork | White with light tint of 371 |

| Satin | Walls, plaster | White with light tint of 371 | |

| Satin | Ceiling | White | |

| Color No. | Finish | Location | Color Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| EAST BEDROOM | |||

| 376 | Satin | Baseboards | Blue-gray |

| 376 | Satin | Doors | Blue-gray |

| 376 | Satin | Other woodwork | Blue-gray |

| 376 | Satin | Chimneypiece | Blue-gray |

| Black | Flat | Fireplace facing | Black |

| Flat | Walls, plaster | Off-White | |

| Flat | Ceiling | White | |

| 43 | |||

| NORTHEAST BATHROOM | |||

| 421 | Satin | Baseboard | Brown |

| Satin | Door | White with slight tint of umber | |

| Satin | Other woodwork | White with slight tint of umber | |

| Satin | Walls, plaster | White with slight tint of umber | |

| Satin | Ceiling | White with slight tint of umber | |

| WEST BEDROOM | |||

| 380 | Satin | Baseboards | Blue-green |

| 380 | Satin | Doors | Blue-green |

| 380 | Satin | Chimneypiece | Blue-green |

| 380 | Satin | Other woodwork | Blue-green |

| Flat | Fireplace facing | Black | |

| Flat | Walls, plaster | White with light tint of 380 | |

| Flat | Ceiling | White | |

| NORTHWEST BATHROOM | |||

| 421 | Satin | Baseboard | Brown |

| Satin | Doors | White with light tint of umber. | |

| Satin | Other woodwork | White with light tint of umber. | |

| Satin | Walls, plaster | White with light tint of umber. | |

| Satin | Ceiling | White | |

NOTES CONCERNING CONDITION OF OLD MOODY HOUSE

During the early part of 1929 there was extended discussion of what to do with the Moody (Roper-Lee) House since it was a house that could readily be rented if minor changes were made. The architects examined the house carefully to determine its condition before deciding what renovations were necessary. The following notes about the condition of the various parts of the old house were prepared by Singleton P. Moorehead, and are dated April 5, 1929.

FRONT ELEVATION

- 1.Foundation walls.

Brick recently repaired, patched, and repainted. In good shape. Openings have been repaired and grilles newly made along old, colonial lines. No sash - but rebates have been left so that new sash may be inserted to thickness of 1 ¼".* - 2.Weatherboarding.

Old and beaded with two patched areas - one at mid-height of wall toward west end and the same towards east end. These patches are of plain weatherboards. All in fair shape.* - 3.Windows.

East window is old - sash trim and frame. New blinds. Sill is new.*

West window.

Old sash, trim and frame. Sill bad, ought to have new one.*

Center window.

All old, new blinds. Sill in bad shape, and ought to be made new.* - 4.Front door and transom.

Door is Greek. - 5.Cornice.

In good shape but for renailing and repairs of a minor nature. Cornice is Colonial and a nice one.* - 6.Roof.

Shingled in wood and in very bad repair. New roof necessary. - 45

- 7.Dormers.

Colonial. Sash are new - condition of them (dormers) alright but need minor repairs. Roofs of shingles and in very bad condition. New ones needed.* - 8.Chimneys.

All chimneys at all elevations are in good exterior repair and need only minor repairs, repointing etc.*

WEST ELEVATION

- 1.Foundation wall.

Brick, repaired and repointed. South of chimney is patched with new brick in hit or miss fashion, but condition is serviceable. Opening boarded up but has new grille. See grille notes on North Elevation.* - 2.Bulkhead.

Recently built. Tar Paper roof. Steps of concrete, as is foundation.* Character rather poor. Door beaded vertical sheathing with H & L hinges. - 3.Weatherboards.

New and plain. Do not line with those of North elevation or those on kitchen addition. Old window has beaded sill once continuing line of former beaded boarding, but new does not coincide at this point. All in good shape. Good for re-use with minor repairs and renailing.*

Original spacing has been disregarded. - 4.Window.

Old trim, sash, frame and shutters. Shutters panelled with Hell [H-L] hinges. Sill of window badly worn by weather - bead weathered away. Otherwise with minor repairs window etc. O.K.* - 5.Barge Board.

Plain and badly weathered. - 6.Kitchen.

All in good shape - Roof is tin.

SOUTH ELEVATION

- 1.Porch.

Upright and lintels need to be trued up, but material is O.K. Posts narrow and have small champer on the corners. Roof is tin. Floor is bad and of different size materials. Joints North and South. Steps of stone fragments at west - red sand stone - are nice and worn. Wood steps at center are in bad shape. Treads must be new.* - 46

- 2.Weather Boards.

To West of door are beaded and old. To East of door are new and plain and joints or spacing do not continue. Need. minor patching and renailing et cetera.* - 3.Windows.

Three new ones - frame, sash and plain flat trim. Looks stock.* 1 East of door old trim, sash et cetera needs some minor repairs.* - 4.Door.

Greek 2 panel. Trim flat and plain.* - 5.Roof Bad.

Part tin, part shingle. Juncture with kitchen full of dead leaves and twigs and dirt, needs cricket. Must have new one. - 6.Dormers.

Sills bad and trim at sills needs repair.* Sash Greek 12 light. Roofs must be new. All bad. Kitchen is O.K.*

EAST ELEVATION

- 1.Foundation wall.

Toward rear is in need of repainting and repair. Opening toward front repaired, repainted and new grille - but no sash. See grille notes on North Elevation. - 2.Stoop.

In bad repair - needs to be considerably trued up et cetera. - 3.Weather Boards.

All new and plain. Do not space same as old on North Elevation. Window has beaded sills which would have carried through one joint - now spacing misses this - that is North window.* All in good shape but for nailing et cetera. - 4.Windows.

First floor - South Window new sash, trim, and frame. Plain, flat trim. North Window all old with old shutters. Shutters can be re-used with considerable repair. Have H-L hinges. Sill less than fair, being weathered and has new piece patched in. Bead weathered off. Recommend new sill.*

Second floor - May not be Colonial. Sash is not colonial. Trim outside of 7/8" in pieces flush with boarding, the 7/8" being width of trim. Needs repairing.* - 47

- 5.Chimney O.K.*

- 6.Barge Board.

Cornice drop gone at front. Barge board is beaded at bottom side on North slope and South slope from ridge as far as old line of back of house - thence to porch at rear continues new and plain. This indicates point at which old building ended and rear sloping roof commences and that the old board was used over.*

SKETCH OF THE WEST END OF THE RECONSTRUCTED MOODY HOUSE. THE INCLINED BULKHEAD AND THE TWO WINDOWS ABOVE IT DID NOT EXIST IN THE OLD HOUSE.

SKETCH OF THE WEST END OF THE RECONSTRUCTED MOODY HOUSE. THE INCLINED BULKHEAD AND THE TWO WINDOWS ABOVE IT DID NOT EXIST IN THE OLD HOUSE.

Singleton P. Moorehead

April 5, 1929

DATING OF A BUILDING

The dating of a house or other building is based upon one or more of the following:

- 1.Actual date of the house visibly signed on its brickwork, framework, etc.

- 2.Literary references such as:

- a.A record stating when a building was started, was in course of erection or completed.

- b.A record which would imply that a house was being occupied at a given date.

- c.Correspondence referring to a house as under construction or as having been completed.

- d.Advertisements referring to a house as for sale or implying its existence.

- e.House transfers by will (wills frequently contain inventories of the contents of a house), sale or default in payment.

- f.Fire insurance policy declarations.

- 3.Documentary evidence such as that furnished by maps; buildings may be indicated on maps, the dates or approximate dates which are known.

- 4.4. Historical references to the building such as found in the record of the meeting at the Raleigh Tavern in 1765 to defy the Stamp Act.

- 5.Existence of original plans or draughts of a building; drawings of exteriors of buildings such as Michel's drawing of the exterior of the Wren Building and of the elevations of Williamsburg buildings shown on the 49 Bodleian Plate (1701, 1702); drawings of interiors of buildings such as Lossing's sketch of the interior of the Apollo Room of the Raleigh Tavern, made in 1850, etc.

- 6.Design characteristics.

- 7.Archaeological evidence and artifacts. (The Division of Architecture of Colonial Williamsburg has developed a chronology of pottery and porcelain which is of assistance in approximating the period of usage of the fragments found on the site.)

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS USED IN ARCHITECTURAL RECORDS

(This glossary is appended as an aid in the interpretation of certain terms used In the report, which are frequently subject to misinterpretation.)

The word "existing" is used in these records to designate features of the building which were in existence prior to its restoration by Colonial Williamsburg.

The phrase "not in existence" means not in existence at the time of restoration.

The word "modern" is used as a synonym of "recent" and is intended to designate any feature which is a replacement of what was there originally and which is of so late a date that it would not properly be retained in an authentic restoration of the building. It must be understood, however, that restored buildings do require the use of modern materials in the way of framing as well as modern equipment.

The word "old" is used to indicate anything about a building that cannot be defined with certainty as being original but which is old enough to justify its retention in a restored building as of the period in which the house was built.

The word "ancient" when used in these reports is intended to mean "existed long ago" or "since long ago." Because of the looseness of its meaning, the term is seldom used but when used, it denotes great age.

"Antique" as applied to a building or materials, is intended to mean that these date from before the Revolution.

51"Greek details," "Greek moldings" etc. refer to the architectural details and treatment introduced with the Greek Revival, which, in this locality, dates from about 1810 to 1860.

"Length" signifies the greatest dimension of a building measured from end to end.

"Width," as used in the reports, means the dimension of a building measured at right angles to the length.

"Depth," applied to the size of a house or lot, is the dimension measured at right angles to the street.

"Pitch" is here interpreted to mean the height from floor to floor.

The expression, "preserved building," refers to a building in its pristine condition, where there has been no replacement of elements, such as stairway, windows, paneling, mantels, flooring, etc. The term "preservation" does, however, imply the making of necessary repairs to protect the building from the weather, decay, excessive sagging, etc.

The term "restoration" is applied to the reconditioning of an existing house in which walls, roof and most of the architectural details are original, but in which decayed parts and some missing elements such as mantels, stairs, window sash, cornices, dormers, etc. are replaced.

"Reconstruction" is applied to a building rebuilt on old foundations, in accordance with documentary evidence as to the character and features of the original structure. The Capitol, for example, is a reconstructed building, which was rebuilt in conformity to the precise specifications for its construction given in the Acts of the Virginia Assembly, 1662-1702. Pictorial evidence, such as the 51a Bodleian Plate, and other recorded measurements and existing old drawings were also used.

When we say "reconstruction (or restoration) was started" the actual beginning of work is meant, not authorization which may occur at an earlier date.

When we say "reconstruction (or restoration)was completed," we refer to the actual completion date of the building and not to the date when the building was accepted.

[A. Lawrence Kocher]

[Howard Dearstyne]

Williamsburg, September 12, 1950

- Memorandum by Hunter D. Farish, Director, Department of Research and Record, concerning the Roper-Lee (Moody) House, dated May 9, 1939, giving a brief history of the House. Also a statement concerning the Roper-Lee property by Farish, dated November 14, 1939.

- Research Report (in manuscript form) on the Moody House by Miss Mary Stephenson of the Department of Research and Record.

- Various other statements concerning the Moody House, Department of Research and Record.

- Unsigned statement, Architectural Department, dated August 17, 1939, giving a description of the original Moody House, apparently based on investigation of foundations by individuals who undertook the measurement of the old house before its reconstruction.

- Field notes with measurements, sketches and notes pertaining to the Moody House. These drawings were made by Thomas G. Little during 1939.

- Measured Drawings of the old house in drawing files of the Department of Architecture. There are seven sheets of drawings, signed by Thomas G. Little and dated July 14, 1939.

- Memorandum of House Naming Committee of January 12, 1934 which gives basis for considering the name "Roper-Lee" as outmoded and suggesting the name "Moody House." Later files of the House Naming Committee confirm the adoption of the name "Moody House."

- Progress Photographs in files of the Department of Architecture.

- Working Drawings used in the reconstruction of the Moody House in files of Department of Architecture. 53

- Correspondence concerning the Moody House in the General Files, also in the letter files of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn. Architectural glossary, Department of Architecture (Architectural Records).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

-

- BARGE boards

- 22

- Basement windows

- 27

- Bibliography

- 52, 53

- Bland, William, one-time owner

- 2

- Blinds, see Shutters

- 28

- Bodleian Plate

- 49

- Bowers, Ralph E., Draftsman on project

- Title Page

- Brick House Tavern

-

- Stairways of

- 11

- Brickwork

- Brush-Everard House

-

- Example of careful Restoration

- 15

- Bulkhead

- 24, 25

- Precedent for

- 25

-

- CAMPIOLI, Mario E.

-

- Revised first floor plan of House (1950) by,

- Title Page

- Reproduced

- 13

- Chairrailings

- 35

- Chimney, central, of first house

- 5, 8, 9

- Chimney, corner type

- 9, 11

- Chimneys

- Chorley, Kenneth

- Closet, leanto

- 26

- College map

- 1

- Color

- Color notes by S.P. Moorehead

- 36, 37

- Color patches

- 37

- Committee of Advisory Architects,

-

- Restoration code by

- 15

- Condition of house (1929),

- Connecticut house plan

- 9

- Corner boards

- 21

- Cornice, front exterior

- 21

- precedent for

- 21

- Cornice, interior

- 35

- Cornice, rear exterior

- 22

- Custis, John

-