Nicholas-Tyler House Archaeological Report, Block 4-1 Building 4AOriginally entitled: "Nicholas-Tyler House, Block 4 Area A, Report of Excavations Conducted"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1077

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

Draft

NICHOLAS-TYLER HOUSE

BLOCK 4 AREA A

REPORT OF EXCAVATIONS CONDUCTED

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Introduction | p. 1 |

| Site History | p. 2 |

| The Archaeological Evidence | p. 4 |

| The Artifacts | p. 9 |

| Conclusions | p. 12 |

| Notes | p. 16 |

| Appendix I. Summary of Excavation Register Numbers Mentioned in Text | p. 17 |

| Appendix II. Analysis of Architectural Samples... | p. 19 |

| Figure 1.Frenchman's Map and 1931 Excavations Following | p. 3 |

| Figure 2. 19th-Century Print of Magazine " | p. 8 |

| Lyon G. Tyler print (see files) | |

| Figure 3. Architectural Finds " | p. 11 |

| Figure 4. Site Plan | Rear folder |

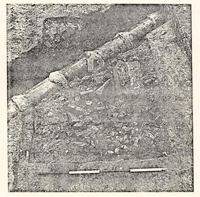

| Plate I. Rubble and architectural fragment in fill of robbed chimney foundation. | |

| Plate II. Northwest corner of excavated chimney foundation. | |

| Plate III.Ca.1860's Tyler House. |

Plate I.

Plate I.

Partially excavated robbed chimney foundation (E.R.1989E, F, G), cut by modern sewer line. Note fragment of stone step in top of fill. From north.

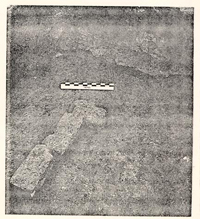

Plate II.

Plate II.

Northwest corner of excavated chimney foundation (E.R.1989G). Several brickbats remain in situ packed along interior foundation wall. Note the mortar adhering to the face of the hole. From the southeast.

INTRODUCTION

In December, 1978, excavation took place at the site of the Nicholas-Tyler House (Block A, Area 4). Work undertaken in 1931 and in 1968 had shown the site to be one of structural complexity, made more obscure by poor stratigraphy. The Department of Archaeology was called in by the Department of Architecture in advance of reconstruction work. The project's goal was to explore the ground on the east side of the 1931 courthouse in order to locate evidence for or against walls extending out from the cellar found in the earlier excavations. It was believed that a discrepancy between the 40' colonial cellar and the approximately 58' length recorded in 19th-century insurance plats could have been due to an extension to the east of the original structure.

The excavation exposed the foundation for a chimney at the east end of the building, as well as lines of post holes for fences on the north and east sides of the house. Although no walls had survived, the dimensions of the building were deduced from several factors: a center line based on successive porches to the front door, the position and angle of the chimney foundation and the orientation and terminal points of fence lines. Additions had been made to each end of the original building, making a 58' length. Artifactual evidence was scanty, but did suggest that the work took place some time before ca.1820 and most probably in the 18th century. It is proposed that the additions were made by John Carter to a building occupied by Robert Carter Nicholas, but possibly constructed in the first half of the 18th century. According to an insurance plat, the house was 58' long in 1801, which confirms the archaeological conclusions.

SITE HISTORY

It will not be necessary to recount at length the history of the site, as it is fully detailed in Mary Stevenson's research report1 and summarized in the 1968 archaeological report2. The salient historical points are:

- 1.The property was bounded by England Street, Ireland Street, and Francis and was comprised of nine colonial lots.

- 2.By 1724 the James City County Courthouse was erected on the property, probably near its northeast corner.

- 3.In 1770, Robert Carter Nicholas bought the property at public auction and sold it in 1777 at which time his house was described as being "large and commodious, having four rooms on a floor, and is in pretty good repair."3

- 4.The merchant Robert Carter bought the property in 1777 and made repairs and alterations in 1778-79 and 1784-85.4

- 5.In 1801, an insurance plat described "a wooden dwelling house 58 feet long by 32 feet. Two stories high underpinned with bricks 3 feet above the surface of the ground."5

- 6.Despite numerous changes in ownership, the house appears to have remained unaltered until 1837, when an insurance policy of January 5, 1838 states that a 16'0" x 16'0" kitchen had been added to the west end of the house, now occupied by John Tyler."6

- 3

- 7.The house was entirely destroyed by fire in 1873, after having no reported fire damage since 1779, when a portion of the roof was burned.7

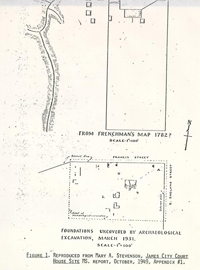

In 1931, the Nicholas-Tyler House was archaeologically explored, exposing foundations on a plan8 close to that represented on the Frenchman's Map (see Figure 1). The main structure was not however, a 32' by 58' brick foundation, but a 32' by 40' cellar. The two flanking buildings were then reconstructed, and the north wing of the new county courthouse was built over, and protected, the colonial foundations of the cellar. Records of the excavation are scanty, but photographs showed that building material had been placed on the ground surrounding the foundations. It was consequently suggested that the 1931 excavators were limited to the 40' cellar and that the remaining 18'-20' may have lain beneath lumber stacked up east and west of the cellar.

When minor construction work took place at the west end of the courthouse wing in 1968, archaeologists were called in to investigate. No evidence for a west wall was found, but a small stretch of robber trench was found running east-west on the line of the cellar's south wall, indicating that an addition had been made to the original structure at the southwest corner.9 This was believed to have represented the 1837 kitchen. Modern utility trenches and construction work of the 1931 courthouse had complete destroyed much of the archaeological evidence west of the house, but a portion of one major feature survived, a shallow cutting filled with destruction rubble dating to the 19th century.10 The 1968 report concluded that the missing length of the Nicholas Tyler House was probably on the east side of the cellar foundation

Figure 1. REPRODUCED FROM MARY A. STEVENSON, JAMES CITY COURT HOUSE SITE MS, REPORT, OCTOBER, 1949, APPENDIX #1.

4.

and recommended that a thorough archaeological examination be made of that area before any reconstruction was undertaken.

Figure 1. REPRODUCED FROM MARY A. STEVENSON, JAMES CITY COURT HOUSE SITE MS, REPORT, OCTOBER, 1949, APPENDIX #1.

4.

and recommended that a thorough archaeological examination be made of that area before any reconstruction was undertaken.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Confronted with the task of locating a possible east end to the Tyler-period building, the archaeological staff decided to dig 10' squares (E.R. 1987/92, 1988), at what might be the corners of a structure 56' to 60' long, projecting east beyond the 40'0" length of the cellar exposed in 1931. These squares were soon connected by a rectangular area (E.R. 1989), and the western edge of the excavations was expanded to 2'6" of the courthouse wall. Further excavation (E.R. 1990, 1991) took place north of the house, in order to establish fence lines and the sequence of porches. It was quickly seen that no old soil layers remained, as the site had been plowed in the late 19th century and badly disturbed during the 1931 construction work and subsequent utility trenching. Features cut into the natural subsoil survived in a truncated state, but none of the brick work mentioned in the documents and shown on the photograph remained.

CHIMNEY FOUNDATION

The most important single feature of the excavation was a vertically-sided rectangular hole, measuring 7'3" by 4'6" and 1'7" deep, which was cut through by a 3' wide sewer trench (see Figure 4, Plate I). The hole was filled with brickbats and mortar rubble (E.R. 1989E, F, G), throughout which was found strong evidence for the burning of a building, i.e. burnt plaster and mortar, pieces of melted window glass, fire hardened nails, and 5. heat-cracked stone step fragments. A fragment of a floor board showing tongue and groove working was preserved in a charred stat (for details, see Appendix II). Datable artifacts include mid nineteenth-century chimney firebricks, cut nails and a scorched piece of an ironstone plate (E.R.1989G), which should readily date the filling of the hole to 1873 when the Tyler House burned to the ground.

Identification of the hole remained in doubt until nearly all of the rubble fill had been removed. A line of roughly laid bricks then appeared, indicating that the feature was a robbed foundation for what must have been a large chimney. Subsequent careful cleaning of the surfaces revealed the mortar "ghost" images of brick courses up the sides of the hole. Similar stains on the bottom of the hole indicate the edge of brickwork for a base course which seems to have been one brick width's smaller on the north side than the next course above (see Figure 4, Plate II). The footings are estimated to have been 1'3" wide, forming a hollow rectangle, while the rough brickwork was not actually part of the foundation, but simply brickbats, chopped and pressed against the interior face of the foundation. The line of the mortar stains and brickbats with the hole is not quite parallel to the foundation hole itself; the chimney foundation appears to be at a 3° angle to the site grid, while its hole was at a 5° angle. The cellar foundations discovered in 1931 were at a 2° angle to the grid. An iron lightning rod was found protruding a few inches into the bottom of the chimney foundation and leading off in an easterly direction, but it could not be determined if the lightning rod was an original fixture.

6.The chimney foundation was 8'0" east of the cellar and would be about 6'0" behind the estimated position of the building's north wall. The placement of the chimney and the late date of its destruction makes it certain that it was the northeast chimney in the photograph taken of the building (see Plate III). The photograph suggests that it was an exterior chimney, and nothing was found by excavation to contradict that assumption. The east wall of the 19th-century building lay, therefore, near the western side of the foundation hole. The photograph, however, clearly shows a second chimney rising above the east end of the building. There is no archaeological evidence for another chimney at the east end of the building, although all the area along the presumed wall line was carefully excavated. Either the chimney had extreme shallow foundations, as had the wall footings, or it lay on the south wall more than 4'0" from the southeast corner, or was inset into the house. The drawing of the Tyler House after 1838 (Figure 2) illustrates the two eastern chimneys, but there is also the suggestion that the "missing" chimney was placed decidedly west of the one located by excavation.

OTHER FEATURES

As stated above, no true soil layers had survived the landscaping for the courthouse, and plow scars were found cutting into natural and early features, indicating that the site had been plowed in the period following the burning of the Tyler House and the 1930's when it was simply an empty field. The excavations north of the courthouse revealed a similar loss of stratigraphy, further complicated by a sewer trench extending nearly 6'0" out from the wall line. In the eastern area (E.R.1987-89), digging 7. exposed what appeared to be a series of post holes on a N-S line, 14'0" east of the cellar wall, lying partially under the balk. Some of the holes had molds which may have been sealed before Nicholas bought the property, while others were dug later. The remaining holes at the east end of the building formed no clear pattern, but several contained pink-colored brickbats with shell mortar, suggesting a construction date coinciding with the demolition of early 18th-century masonry.

An east-west series of post holes were discovered 8'0" beyond the north end of the courthouse. These features represented fences indicated on the 19th-century photograph (Plate III) and the slightly earlier print (Fig. 2). Replacement holes for the fence suggest that it stood for a long time, perhaps several generations. Two pairs of large post holes (E.R.1990K, L and E.R.1991C, E) marked the position of a 14'6" wide porch and its 11'6" wide replacement. The line of the porch as revealed by these holes is at a 2° angle to the site grid, the same angle as that of the cellar foundations.

Evidence for fences leading to the flanking buildings was also found. One post hole on a northwest line (E.R.1991M-PI had been replaced at least once and suggests a long use of the fence line to the "laundry." A series of holes were located at the northeast; they also exhibit signs of repair, and perhaps the 3'6" interval between the pairs of holes at the southwest end of the line (E.R.1987G-J, E.R.1992A-D) indicates the insertion (and perhaps replacement) of a gate at the corner of the house.

8.The east-west fences along the front of the house ran in a fairly straight line off the second porch front, 1'0" further south than the earlier, wider porch. Post hole intervals (7'6"-8'0") are similar, so that the fences presented a mirror image of each other, reflecting a geometry based on a center line at the middle of the porch, obviously the front door of the house. This is the view depicted in the print drawn after the 1838 addition of the kitchen wing (see Figure 2), though it should be noted that the western fence had been removed by the time the later photograph was taken. The photograph does show the remaining front fence and the fences leading to the ancilliary buildings. There is even a suggestion of the gate indicated by the archaeological remains. The 20' wide, brick-based porch of Figure 2 and Plate III had probably been built during the alterations of 1838, and it seems, simply inserted into the east-west fence line. The western fence decayed and was removed, while the eastern fence was repaired or partially rebuilt by the seating of a new post (E.R.1990C,D) at the corner of the porch and the replacement, slightly off its original line, of the next post to the west (E.R.1990E).

Before the construction of the house, and apparently before any colonial occupation of the site, a natural erosion gully had crossed the area of occupation from northwest to southeast. This feature was not fully excavated, but its observable depth, where cut by later features, suggests that it descended toward the north, in the direction of the little dell on the other side of Francis Street.

Print from Lyon G. Tyler

Williamsburg, The Old Colonial Capitol

Richmond, 1907.

See Architectural Research Files

Fig. 2

THE ARTIFACTS

As noted above, late 19th-century plowing and the landscaping accompanying the construction of the 1931 courthouse completely removed all stratigraphy and with it nearly all of the artifacts which must have accumulated around a structure occupied for more than a century.

There were few stratified artifacts and even fewer noteworthy ones. In the mold of one of the post holes along the front of the house (E.R.1990E) was a part of a delft lid to an item of a garniture, the manufacture of which is attributed to ca. 1720. Sherds were also found of a burnished red ware, believed to be New World in origin, perhaps Mexican. One was a small body sherd found in a late deposit (E.R.1988D) and the other was a fragment of a simple, slightly lipped rim, found in what appeared to be a colonial post hole (E.R.1988K). The complete body (without neck of a wine bottle dated to ca.1750-ca.1760 was found in the mold (E.R.1989X) of the eastern series of post holes. The bottle, once broken, must have been quickly disposed of for its body to remain intact, suggesting that the hole could have been filled before the occupancy of Robert Carter Nicholas.

THE ARCHITECTURAL FINDS

The excavation of the chimney foundation produced several significant artifacts which have been examined by Messrs. Buchanan and Waite of the Department of Architecture. Their comments were extremely helpful and have been incorporated into the text (for a detailed list of architectural samples, see Appendix II).

9.Plaster: One fragment recovered showed signs of having been whitewashed at least 5 times. In the samples studied no evidence of hair could be seen. It was determined that at least one plaster fragment came from the inside of a fireplace; it was thin and too smooth for a flue lining, but not painted, so unlikely to have been on the fireplace facing. A few mortar fragments were found that had been painted red over earlier layers of whitewash.

Mortar: All the mortar recovered had quantities of shell in it. On a reused brick, a pale cream colored mortar had been covered by a light gray mortar. There was no example, however, of the yellow sandy mortar which becomes common at the end of the first quarter of the 19th century. One mortar fragment was found which had come from the inside of a wall, painted red similar to Wetherburn's basement.

Bricks: Three types of bricks were recovered in the excavations: soft pink 18th-century brick, harder red brick, and off white 19th-century firebrick. The pink brick was similar to that observed in the cellar construction, and was fairly rare. The most common brick was the red, examples of which were in situ in the chimney foundation.

A brick voussoir had come from the left hand side of a jack arch. The narrow "header" end was somewhat blackened by smoke, while the other sides had been covered by a lime putty, except for the exterior "stretcher" face which had a scored line cut 3" from the wider end, a decorative feature used in an alternate sequence.

Two reused bricks were of the same pink color as the bricks of the cellar foundations. Both bricks had been remortared, with 11. light gray shell mortar over a pale cream shell mortar. They had been reused at the corner of a structure, as two sides were unmortared but had been painted red, and in one instance the paint overlay an area of earlier mortar.

Several pieces of molded firebricks were recovered, but not enough to attempt a reconstruction. It is believed that they were ordered in "sets" or "kits" from the manufacturer, and that they were used for stoves as well as for fireplace linings. Their date is thought to be from ca.1850 onward.

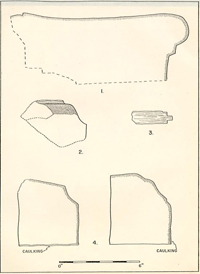

Stone: The robbed chimney foundation yielded fragments of a molded base (No. 4,Figure 4), once set into or onto the ground surface, as evidenced by a tar calking along two sides. It is believed that the base was not related to the house, but had supported a piece of garden sculpture or decoration. A sundial was suggested, as statuary or birdbaths were apparently not common until later in the Victorian period. The red, gritty, rather weak granite of the base did not come to Williamsburg until the 19th century.

A harder granite, yellow in color, with red iron spotting was used for two large stones, the larger of which had been roughly chiseled and therefore may have been a support member hidden behind dressed stones. The second piece (No.1,Figure 4), was a large stone step which showed a good deal or wear on the tread, suggesting a long period of use. Similar stone was used in the steps at Mount Airy, near Richmond, so an 18th-century date is not unlikely Although the photograph clearly shows brick steps at the front porch, it is possible that earlier steps were simple covered by the porch, or earlier porches. The original stone steps at Carter Grove were covered by a 19th-century porch.

FIGURE 3. ARCHITECTURAL FINDS.

FIGURE 3. ARCHITECTURAL FINDS.

The post mold carrying the western support to the second porch (E.R.1991B) contained a large number of fragments of the same yellow stone. Several pieces showed signs of tooling, and there was one fragment of a molded base or cornice (No.2, Figure 4) It seems unlikely that this fragment came from steps; it may have belonged to a formal garden architectural piece.

Wood: Large quantities of charred wood fragments were found in the robbed chimney hole. Most appeared to be warped and unidentifiable pieces of pine floorboards, of little further note, but one fragment did preserve carpentry details (No.3, Figure 4). The male member of a tongue-and-groove joint was 3/16" wide and 1/4" long, while the underside of the board exhibited a shallow seat for the floor joist below. The upper surface of the floor board had been heavily charred, and it is possible that the piece came from the ground floor where it was more likely to have been so unevenly burned.

CONCLUSIONS

The 1978 excavations were more successful than was thought possible, once it was realized that no layers of occupation had survived around the courthouse. The discovery of a chimney foundation, robbed and filled with debris from a building burned in the 19th century gave the position of the northeast chimney in the ca.1860 photograph. The placement of the terminal post hole of the northeast fence line proved that the chimney must have been on the exterior of the end wall. The discovery of the position of porches to the north door gave the location of the door, and therefore the center line of the Tyler-period building. 13. The distance from the center point to the east wall, as indicated by the edge of the terminal post hole of the northeast line, was 29'0". The northwest fence line, from the corner of the "laundry" through the one post hole discovered in the excavations, would have intersected the line of the north side of the building just beyond 29'0" from the center of the porch. All the evidence; therefore, indicates that the building destroyed in 1873 was 58'0" long and represented the cellar structure plus 9'0" addition at either end.

The excavations have significantly reduced the structural complexity to three clear phases: the construction of the original cellar, the addition of the east and west extension, and the construction of the kitchen and the wider front porch. The last phase was recorded on an insurance plat dated January 5, 1838 and probably took place in 1837. There was no yellow 19th-centurl mortar at all in the chimney foundation discovered in the 1978 excavations, though the shell mortar present could possibly be as late as the second decade of the 19th century. The question is, who built the additions?

Documentary evidence indicates that John Carter spent money on brickwork and plastering in 1777-79 and 1783-85, but the details of the charges refer to only minor, repairs to the house, while most of the work was spent on substantially reworking the kitchen, on building a springhouse, and on such jobs as plastering "11 rooms... including 4 closets," "painting porch and ditto steps," and "building a pair of steps + repairing 1 pair of ditto." The eight rooms and nine closets mentioned in his 1783 advertisement for sale12 suggests a building already enlarged beyond the 30' x 40' cellar. If such work under Carter had simply gone 14. unrecorded, one might conclude that the previous owner, Robert Carter Nicholas, was the one who made the alterations and additions to the house, between his purchase of the property in 1770 and its sale in 1777. The advertisement for that sale describes the house as "large and commodious, having four rooms on a floor and is in pretty good repair." It does not mention the nine closets, so the additions may very well have been built by John Carter between 1777 and 1783. In fact, archaeological evidence from the 1968 excavation suggests that the western 13 addition was constructed post ca.1780.13

It is unlikely that a house described as "in pretty good repair" could be only five or six years old. Thus the foundation discovered in 1931 should belong, in the main, to a structure erected before 1770, as is suggested by the pink bricks and cream colored shell mortar which may be most typical of the first half of the 18th century. The only recorded structure on the property until Nicholas' occupancy was the county courthouse, constructed sometime after 1715 and before 1724. Could it be the same structure? Re-excavation of the cellar should readily answer the question.

I would like to add a final note of appreciation for the support and cooperation which the Department of Architecture gave us during the three weeks of excavation. In particular, the experienced advice of Paul Buchanan-and the consistent availability of James Waite, for questions and interpretative conferences, made our task much easier. Some of the conclusions arrived at in this report originated, in fact, from suggestions 15. by James Waite. These discussions quickly exposed problems of architectural analysis and interpretation, and we were able to plan our excavations (and amend those plans) accordingly.

NOTES

APPENDIX I

| E.R. 19876-4.A. | Post hole around 1987F, 1'5" x 1'2" x 1'1" deep. Fill of sandy brown loam. |

| E.R. 1987H | Post mold, 7-½" x 8" x 1'8" with a flat bottom. Square shaped, filled with light brown loam with brick chips and mortar flecks. |

| E.R. 1987J | Post hole around 1987H, 2'2" x 1'9" x 9" deep. Fill was light brown loam. |

| E.R. 1988D | Yellow-orange clay lumps mixed with brown loam Lies beneath 1988C, extending in patches through much of square. 2" thick. |

| E.R. 1988K | Post hole, 1'2" wide, 9" extant E-W, 11" deep. Cuts the gray loam-filled gully. Fill is brown loam with clay and brick chips. It is on line with 1988H. |

| E.R. 1989E | Top of rubble deposit; some brown loam in it, possibly disturbed by root action. 1" thick, but continues 2"-3" into northwest corner of hole. |

| E.R. 1989E | Center of rubble, has much ash in it. 8" deel 2'0" wide. Contains much burnt material -burned stone, brick, mortar, nails and-melted glass. Slopes down to west, comes to within 6" of west and north sides. |

| E.R 1989G | Rubble, brickbats and mortar fill throughout most of hole. Gray to pink in color. Some charcoal pieces continue from 1989E down into 19896, but at north end only. Note: Contains burnt fragment of ironstone. |

| E.R. 1990C | Post mold surrounded by post hole 1990D. Darl loam fill with brick chips. Vertical sides and flat bottom. 6" x 6" x 3" deep. E.R. |

| E.R. 1990D | Post hole for post mold 1990C. Mixed dark any light brown loam fill. 1'0" x 1'1" x 3" deep. Vertical sides and flat bottom. E.R. |

| E.R. 1990E | Post mold in 1990F, is also probably replacemE hole, as its north half lies beyond the edge of the hole. 10" E-W, 1'9" N-S, 9" deep. Gray loam fill |

| 18 | |

| E.R. 1990K | Post hole or pier hole cut by 1990J. 2'4" x 1'10" x 8" deep. Sloping sides, rectangular hole. Cuts 1990L. Has many brick chips in light brown loam fill with clay lumps. Is irregular on north side -- stepped down to south, 2" to 8". |

| E.R. 1990L | Hole cut by 1990K. Few brick chips. 1-'7" x 1'10" x 6" deep. Mottled loam and clay fill. Vertical sides, flat bottom. Could be for earlier porch support. |

| E.R. 1991C | Post hole surrounding mold 1991B. Mixed sandy loam fill with lumps of yellow clay and brick chips. 1991C cuts post hole 1991E. 1991C is a stepped post hole with vertical sides and flat bottom. |

| E.R. 1991E | Post hole surrounding post mold 1991D. 1'10" 1'10" x 7" deep, vertical sides, flat bottom. 1991E is cut by hole 1991C. Fill is a gray sandy loam. |

| E.R. 1991M | Post mold lying within post hole 1991P. 8" x 8" x 1'0" deep, vertical sides, flat bottom. Mixed gray and white loam fill with some yelloi clay. |

| E.R. 1991N | Post hole lying within post hole 1991M. Mixed gray loam fill. 1'9" x 1'2" x 9" deep, vertic. sides. Hole is 'L' shaped. |

| E.R. 1991P | Post hole surrounds 1991M, 1991N. 1'10" x 2'0" x 7" deep. Mixed clay and loam fill. |

| E.R. 1992A | Post mold surrounded by post hole 1992B. Brow loam fill, with some brick chips. Vertical sides and flat bottom. 7" x 7" x 10" deep. |

| E.R. 1992B | Post hole for post mold 1992A. Mixed loam fil with some brick chips. Hole is cut by 1992D. 1'1" x 11" x 10" deep. E.R. |

| E.R. 1992C | Post mold for post hole 1992D. Brown loam fil 9" x 8" x 7" deep. Vertical sides, curved bottom. |

| E.R. 1992D | Post hole around mold 1992C. 1'5" x 1'4" x 7" deep. Post hole cuts hole 1992B. Mixed fill with brick chips. |

| 21. | |

| PLASTER: | |

|---|---|

| E. R. 1988H | Light gray shell mortar whitewashed |

| E.R. 1989E | Red paint on whitewash, light gray matrix |

| E.R. 1989F-G | Shell inclusions, whitewash, 5 or more layers on one sample, red paint over whitewash |

| STONE: | |

| E.R. 1989F | Step, 1'1" wide with 1'0" tread, 6" thick, 1'4" surviving length, yellow, iron-streaked granite, burned red |

| E.R. 1989F-G | Base, red granite in five fragments, extant height 7" |

| E.R. 1989K | Light gray limestone, several small fragments E.R. 1991C Yellow iron spotted granite, many small fragments. One shows carving for ornamental base or decoration on steps? |

| WOOD: | |

| E.R. 1989G | 2-1/8" long charred floor board fragment with tongue 3/16" wide, 4/10" long, 7/16" in from surface. Bottom has 1/16" deep cut 6/16" from corner to set board on floor joist. Width survives at 43/48". Other small charred fragments were removed, but as they were without identifiable features, they were discarded. Their widths ranged ¾" thick to 1-½" x 2" and 2" x 4". All were identified as yellow pine. |

[Blueprint]

[Blueprint]