Alexander Craig House Architectural Report,

Block 17 Building 5 Lot 55Originally entitled: "The Alexander Craig House (Vaiden House)"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series—1344

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

Alexander Craig House

Architectural Report

SM Comments

July 27/50

ALK Copy

[Hand-written Notes]

| p. 6 | Include north point as on illus. p. 4. |

| p. 16 | Should be referred to as "restored" house. It is so termed on the final approved house label list and will be in the Guide Book. |

| p. 19 | Brick work "The new brick [add] where exposed to the eye were made etc. etc. [add] where hidden the brick is modern machine made... |

| p. 21 | ¶ 2 "... and of reproduced brick work above" [add] where exposed to the eye |

| ¶ Bond of foundations. I have received in the Howard some questions concerning the ¶. I think we had better review together because the matter is too complicated to cover herein. From restudy of archaeological reports, notes, drawings and photos I think I can clarify the matter somewhat - particularly the "inconsistencies". | |

| p. 22 | Curiously the chimneys are English bond. The foundation well behind the south chimney is and was Flemish whereas at the north chimney it is and was English. |

| p. 23 | Duke of Gloucester street is, embarrassingly, above its Colonial grade in this area. Also the ground about the house has raised throughout the years above its colonial level. Since the |

| p. 25 | Should mention be made of the ancient path which as raised badly to the modern ground level and preserved just as it was. See progress photos and landscape plans. |

| p. 29 | ¶ 2 "...the walls are plastered in the modern manner" [add] except that the finished surfaces are made to present a slightly wavy effect as in local colonial [illegible] |

| ¶ 3 Originally the weatherboards would have been of yellow pine or local poplar. Gulf Cypress was used because it is more permanent - it being impossible now to procure pine or poplar of the same quality as in colonial times. | |

| p. 39 | The brass finial has precedent from an 18th one in Old Court House [illegible] |

| p. 40 | See precedent for porch details in Coleman and other collections of early photos of Wmsburg in arch. dept. files. |

| pp. 43-44 | Handrails of rear porches copied from one on the Toddsbury, Gloucester Co., porch recently removed by an insane owner - not from Bruton |

| p. 44 | For solid porch railing, see Myers House rear porch (Norfolk) in large snapshot book in main drafting room as partial precedent. See remarks on front porch, St. Geo. Tucker House in architectural report. George Benett has seen examples in Penna., Mich. and Delaware. He suggests looking at Wallace's book on "Penna. Farmhouses" |

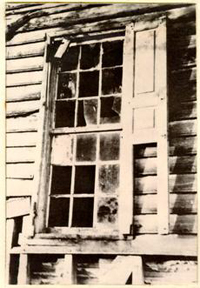

| p. 47 | Muntin and sash details are from original sash found in the building. (See FFF architectural field notes) See also arch'l drawings which show where old sash were reused. This should be mentioned in the report. Should mention be made that upper sash are not fixed & that the bronze parting strip is for modern convenience & as inconspicuous as possible. |

| p. 49 | Interior trim of windows where double molded was copied from pieces of original trim found in the bldg. Ditto for doors. The single molded trim was adapted from it. |

| p. 51 | Should it be mentioned that Maine farm has disappeared? |

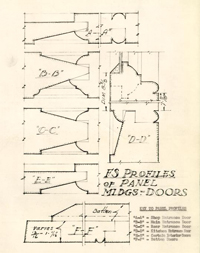

| New interior door panel molds are copied from original doors found in bldg. See arch'l drawings for those frames & trim which were original and were reused in whole or in part. | |

| Exterior door trim not from bldg but elsewhere. | |

| p. 53 | The Craig, Scrivener, Red Lion & Burdettes are all above their colonial levels. |

| p. 53 | Floor nails It was common to use face nails in the large heads as stated, but these were then hammered on each side to produce a thin, roughly rectangular head: [sketch of two nails] which the New York cut nail we use resembles [sketch of a nail] |

| p. 54 | Floor Boards T & G joints were most common - as were splined joints and dowels were often used with either type. I doubt if butt joints can be found except in attics or unimportant areas or in minor outbuildings. This is because they had no underfloor. |

| p. 58 | The preced3ent for the Hall arches should be mentioned: Milberry Fields, St. Mary's Co., Md. |

| p. 76 | Step nosing. F.S. taken from miscellaneous colonial fragments of steps found on the site during archaeological work. |

| General | |

| Hardware (p. 64) A note should be made that the [illegible] cut doors D-1 thru D-5 | |

| Screens Some reference (to glossary or otherwise) should explain this compromise on exterior doors, basement & other windows. | |

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

THE ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE

(VAIDEN HOUSE)

(Reconstructed)

Block 17—Colonial Lot #55

ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE AS SEEN FROM THE SOUTHWEST. THE PAINT-COVERED OLD PORTIONS OF THE WEST CHIMNEYS ARE EASILY DISTINGUISHABLE FROM THEIR UNPAINTED SHAFTS. MARKINGS FOUND ON THE SOUTH SIDE OF THE SMALLER CHIMNEY FORMED THE BASIS FOR THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE WOOD CLOSET LEANTO.

ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE AS SEEN FROM THE SOUTHWEST. THE PAINT-COVERED OLD PORTIONS OF THE WEST CHIMNEYS ARE EASILY DISTINGUISHABLE FROM THEIR UNPAINTED SHAFTS. MARKINGS FOUND ON THE SOUTH SIDE OF THE SMALLER CHIMNEY FORMED THE BASIS FOR THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE WOOD CLOSET LEANTO.

Photograph of Alexander Craig House

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

THE ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE

(VAIDEN HOUSE)

(Reconstructed)

Block 17—Colonial Lot #55

The Alexander Craig House was reconstructed under

the direction of the Department of Architecture of

Colonial Williamsburg, Inc. Perry, Shaw & Hepburn,

Architects, acted as consultants.

Reconstruction was started May 6, 1941.

Reconstruction was completed April 1, 1942.

A. Edwin Kendrew, Director of

the Department of Architecture

Singleton P. Moorehead, Assistant

Director and Designer.

Washington Reed—Head Draftsman

Finley F. Ferguson—Draftsman

C. Vaughan Holmes—Draftsman

Research Report (July 19, 1939)—Hunter D. Farish

Archaeological Drawings (March 2, 1940)—James M. Knight

Archaeological Report (August, 1941)—Francis Duke

This report was prepared by A. Lawrence Kocher and Howard Dearstyne

for the Department of Architecture (Architectural Records).

June 12, 1950

THE ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE

(VAIDEN HOUSE)

Block 17—Colonial Lot #55

OLD PHOTOGRAPH SHOWING FRONT OF ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE, AND AT THE RIGHT, THE SCRIVENER HOUSE, AS THEY APPEARED SOMETIME AFTER 1900. THE SECOND STORY OF THE CRAIG HOUSE AND THE PORCH REPRESENT 19TH CENTURY ALTERATIONS. THE GLAZED DOORWAY AT THE RIGHT IS THE ENTRY TO A SHOP WHICH HAD PERSISTED IN THIS LOCATION FROM ABOUT 1735.

OLD PHOTOGRAPH SHOWING FRONT OF ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE, AND AT THE RIGHT, THE SCRIVENER HOUSE, AS THEY APPEARED SOMETIME AFTER 1900. THE SECOND STORY OF THE CRAIG HOUSE AND THE PORCH REPRESENT 19TH CENTURY ALTERATIONS. THE GLAZED DOORWAY AT THE RIGHT IS THE ENTRY TO A SHOP WHICH HAD PERSISTED IN THIS LOCATION FROM ABOUT 1735.

Photograph of Craig House ca. 1900

The Craig House is a one and one half story, reconstructed, frame structure with a modified A roof. It is located on Colonial Lot #55 on the north side of Duke of Gloucester Street between the Raleigh Tavern and the Scrivener House. Colonial Lot #55 extended 82'-6" along Duke of Gloucester Street and through to Nicholson Street (about 261'-0"). The exact location of Colonial Lot #55 is uncertain (see discussion of the problems arising in the location of Colonial lot lines in Block 17, 2 on page 3 of the Archaeological Report on the Vaiden House Site prepared by Francis Duke in August 1941). The line accepted, until further evidence is forthcoming, as the western boundary of Colonial Lot #55 coincides with the east end of the Raleigh Tavern. The modern lot (the Lucy Vaiden property) extended 117.35 feet eastward from the east end of the Raleigh Tavern, thus occupying the whole of Colonial lot #55, in addition to some 35 feet of Colonial lot #56. The western wall of the old foundation and of the present building which was placed upon it, is about 35'-0" from the west Colonial lot line. From this point the building extends 51'-6" eastward, thus overlapping the line which has tentatively been accepted as the east Colonial lot line. The building is about 7 feet from the street line of Duke of Gloucester Street at its east end and about 8 feet at the west. It extends 30'-7" northward.

From evidence found in the foundations after the building was demolished and in the framing of the house in the course of demolition, the original eighteenth-century house in the Alexander Craig site was built in several successive stages. Facts contained in deeds recorded in the deed book of York County, advertisements in the Virginia Gazette and other documents from 1712 to ca. 1800* also support the supposition that the house was erected at different periods. A chronological summary# of the essential facts contained in the above-mentioned documents is presented here for the light it may throw on the dates of erection of the various parts of the house.

| 1712 | Lot 55, previously owned by Jacob Flournoy, bought by Susannah Allen, "with ... houses, buildings ..." |

| 1716 | Tavern licensed by Susannah Allen. |

| 1717 | Lot 56, previously owned by Wm Wharton, bought by John Marot, with "mansion or dwelling house ..." |

| 1735 | Lot 55 bought by John White, who sold to John Wagnon 480 square feet of it, "beginning in the Southeast corner of the said lot and measuring thence twenty feet on the front line and twenty four feet backwards." Wagnon built a small wigshop. |

| 1736 | Andrew Anderson, wigmaker, bought the wigshop. |

| 1737 | John Pasteur, barber and peruke maker, bought balance of lot 55. |

| 1738 | Gabriel Maupin, tavern keeper, bought Pasteur's holding. |

| 1745 | A 30-foot strip forming the western part of lot 56 "and all houses, buildings ..." was deeded to James Shields, ordinary keeper and husband of Anne Marot. |

| 1752 | Wm. Peake bought the wigshop, which had been improved and probably enlarged by Anderson, and carried on the business. |

| 1755 | Peake sold the shop to Alexander Craig, sadler. |

| 1762 | Joseph Scrivener, merchant, bought Shields' 30-foot strip, "whereon is a storehouse and other outhouses ... and all houses, outhouses, buildings ..." |

| 1771 | Craig bought Maupin's tract, giving him sole ownership of lot 55. |

| 1772 | Scrivener's death. Inventory indicates stock in trade. |

| 1776 | Craig's death. His will is the last definite information until recent times. |

| 1782 | The Frenchman's map shows, east of the Raleigh Tavern, a small building which might be a survival from Susannah Allen's tavern (at least it is near the probable location of the tavern), and a large building which might be the structure later known as the Vaiden House. The next structure might represent the Scrivener Shop, though it is very small indeed. |

| 4 | |

| 1782 continued | Future investigation on the site of the Victoria Lee House may confirm or cast doubt upon this chain of identities. |

| c.1800 | Real estate plats show "Galt" in lot 55 and "Greenhow" in lot 56. But a chain of evidence drawn from insurance policies of 1802-1815 points to the conclusion that Galt occupied not only lot 55, but also about two-thirds of lot 56, leaving only the eastern third to Greenhow. If this is the true conclusion, then Greenhow's name does not properly appear in the history of archaeological area G. Later records of the exact year are not available—the Galt property seems to have passed into the hands of Barlow and later of the Vaiden family. It is not certain that there was not an intervening owner. Miss Vaiden states that her grandfather, Mr. Barlow, bought the house as a young man (c. 1840), and opened store after remodeling the southeast front. |

THE ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE & LOT AS SHOWN ON THE FRENCHMAN'S MAP.

THE ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE & LOT AS SHOWN ON THE FRENCHMAN'S MAP.

Section of the Frenchman's Map

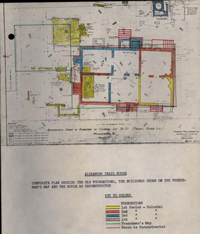

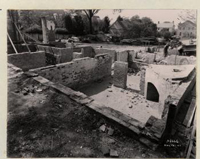

THE OLD FOUNDATIONS DISCOVERED ON LOT #55

Thorough excavations were carried out on Colonial lot #55 in 1940. The foundations uncovered were recorded on a survey map made of the site in March 1940 by James M. Knight (see p.6) and detailed analysis of these foundations was incorporated in the previously-mentioned Archaeological Report made by Francis Duke. The summary of facts concerning the foundations presented below is derived from these two sources. For a fuller consideration of the foundations the reader should consult the survey map and the Archaeological Report.

For the purposes of this report the foundations found on lot #55 will be grouped into four general areas, vis., I, the foundations uncovered at the southwest corner of the lot, comprising the groups designated "A", "B", and "C" on the survey map; II, the foundation of the house proper, designated "D"; III, the foundations directly to the rear of the 5 house, designated "E", "F", and "G"; and IV, the foundation at the north end of the lot, "H", "J", and V, an old foundation at the northwest corner whose exact period of construction has not been determined.

I ("A", "B", and "C"). The foundations found in this group are thought to be the earliest on the lot and consequently may have represented remains of a building or buildings built by Jacob Flournoy and used by Susannah Allen as a tavern. Area "A" was an extensive area of paving within the Alexander Craig House foundation at the west end and two feet below the basement floor. This may have extended beneath the west wall of the Alexander Craig house into area "B."

Area "B."The foundations in this group extended from about 3'-6" west of the wall of the house to within about 6 feet of the west boundary of the lot. They were about 20 feet across from north to south, extending about 7 feet south of the south wall of the house. The salient features of these foundations were a chimney foundation against the north wall on the inside, and due south of this, outside the south wall, three foundation walls which may have formed the outline of an entrance stoop. Francis Duke believes it possible to consider the chimney and stoop as the center axis of a building 40 feet or more in length, the eastern portion of which extended into the area which later came to be occupied by the Alexander Craig House. This may have been Susannah Allen's tavern, since it was the last structure standing on the street-front on lot #55 before the Alexander Craig House was built. (See photo p. 8).

At the northwest corner of the Alexander Craig House was a cellar foundation ("C"), 16 x 16 feet in size, with brick paving and bulkhead type steps at the center of its east wall. This foundation centered on the stoop and chimney of the tavern, and may have been the north end of a wing of the latter, forming the leg of a T plan, or it may have been one of the two

6

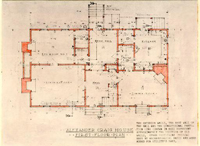

Composite Plan of Craig House

7

as-yet-unidentified outbuildings shown at the rear of the Alexander Craig House on the Frenchman's map (1782). (See photo, p. 8)

Composite Plan of Craig House

7

as-yet-unidentified outbuildings shown at the rear of the Alexander Craig House on the Frenchman's map (1782). (See photo, p. 8)

II Area "D." the Craig House. This foundation or group of foundations was about 50'-10" long by 30'-8" wide. The southwest corner was about 34'-8" from the west line of Colonial lot #55 and 8'-9½" from the north line of Duke of Gloucester Street. The foundation was not quite parallel with the street, its southeast corner being 6'-9½" from the street line.

The rectangular mass of the foundations was built up during Colonial times in four or five installments, the general sequence of which can be deduced from archaeological evidence weighed against historical evidence. The oldest part of the foundation were the walls of the southeast corner space or room which measured 16 feet from north to south and 19 feet from east to west (outside dimensions), and were 13 inches thick. Since Wagnon bought the corner property for £15 and sold it for £40, and since the foundation walls were confined within this original "dividend" of 20 x 24 feet, this room may with confidence be dated during Wagnon's occupancy, between 1735-1736.

OLD BASEMENT OF THE ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE VIEWED FROM THE SOUTHEAST. THE CORNER FIREPLACE, FREE-STANDING PIER AND THE WALLS NEAREST THE OBSERVER DEFINE THE OLDEST PART OF THE HOUSE, I.E. THE SITE OF WAGNON'S WIG SHOP OF 1735.

8

OLD BASEMENT OF THE ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE VIEWED FROM THE SOUTHEAST. THE CORNER FIREPLACE, FREE-STANDING PIER AND THE WALLS NEAREST THE OBSERVER DEFINE THE OLDEST PART OF THE HOUSE, I.E. THE SITE OF WAGNON'S WIG SHOP OF 1735.

8

THE FOUNDATIONS (AREA "B")OF WHAT WAS POSSIBLY SUSANNAH ALLEN'S TAVERN, WHICH MAY HAVE STOOD ON THE LOT AS EARLY AS 1712. THE OBSERVER IS LOOKING EASTWARD TOWARD THE WEST END OF THE UNRESTORED ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE.

THE FOUNDATIONS (AREA "B")OF WHAT WAS POSSIBLY SUSANNAH ALLEN'S TAVERN, WHICH MAY HAVE STOOD ON THE LOT AS EARLY AS 1712. THE OBSERVER IS LOOKING EASTWARD TOWARD THE WEST END OF THE UNRESTORED ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE.

BASEMENT PAVING AND STEPS OF AN OUTBUILDING OR OF WHAT MAY HAVE BEEN A PORTION OF SUSANNAH ALLEN'S TAVERN.

9

The most prominent feature of this room was an inside corner chimney in the northeast corner, which was coupled with a second corner chimney in the later room to the north.

BASEMENT PAVING AND STEPS OF AN OUTBUILDING OR OF WHAT MAY HAVE BEEN A PORTION OF SUSANNAH ALLEN'S TAVERN.

9

The most prominent feature of this room was an inside corner chimney in the northeast corner, which was coupled with a second corner chimney in the later room to the north.

South Central Room

The first addition to the Wagnon shop was either the space to the west (referred to in Duke's report as the "south central room") or that to the north (the "northeast room"). Duke concludes that the south central room was built first because of evidence found in the brickwork of the west wall of the shop, and for other reasons. The foundations of this room enclosed an area approximately 15'-6" wide by 15'-0" deep. The south wall of the room was 9" thick and the east and north walls 13 inches, but the latter were probably replacements of earlier 9" walls. Outside the south wall near the east end was the foundation of an early stoop, while further west and overlapping this was the foundation of a later entrance. This was on the center line of a rear foundation of the same period.

Northeast Room

It is not known with certainty whether the next addition was the southwest or northeast room. Duke thinks that the Susannah Allen tavern stood until 1771 and that the southwest room was not added until that date or later. He believes, on the other hand, from evidence found in the brickwork of the northeast room and for other reasons, that the latter room was built before 1752. The inside dimensions of the northeast room were approximately 16'-9" (width) by 13'-3" (depth). The walls are 13" thick. The south wall of the room consisted only of a pier and a wing wall jutting from the corner chimney mentioned previously. There were three basement windows in the room, all of them late and 10 all of which had been bricked up. In the west wall was an original door opening which had been closed up.

Southwest Room

The southwest room as before noted, was probably built after 1771. It was about 14'-6" square. The original walls of this space were 9" above and 13" below. This room originally had no basement but one was later excavated. The foundations of the larger of the two chimneys of the west wall of the house was incorporated in the west wall of this room. The early paving ("A") found in the west portion of this space has already been discussed.

North Central and Northeast Rooms

The entire northwest corner of the L formed by the northeast room and the three south rooms seems to have been filled in at one time by the building of two rooms at the north center and the northwest corner. The house had now assumed its final shape (as of the colonial period) with a full basement and six medium-

VIEW SHOWING BULKHEAD STEPS AND JOINTS OF ONE-TIME EXPOSED WEST WALL OF ORIGINAL SHOP ON EASTERN PORTION OF LOT.

11

sized first floor rooms. It is not known when these rooms were added but Duke believes it most likely that they were built between 1771-9. The most conspicuous feature of the foundation walls of the northwest room is the smaller of the brace of chimneys of the west wall of the house. Outside the north wall of the north central room at the northeast corner was a bricked-in bulkhead opening, and beside it a 9-inch stoop foundation centering on the front stoop foundation already mentioned.

VIEW SHOWING BULKHEAD STEPS AND JOINTS OF ONE-TIME EXPOSED WEST WALL OF ORIGINAL SHOP ON EASTERN PORTION OF LOT.

11

sized first floor rooms. It is not known when these rooms were added but Duke believes it most likely that they were built between 1771-9. The most conspicuous feature of the foundation walls of the northwest room is the smaller of the brace of chimneys of the west wall of the house. Outside the north wall of the north central room at the northeast corner was a bricked-in bulkhead opening, and beside it a 9-inch stoop foundation centering on the front stoop foundation already mentioned.

III ("E". "F". "G"). The foundations in this group comprise those of a well and well house, designated "F" on the survey map; a kitchen, "E", and a garden walk, "G." The well and well house were located directly north of the east end of the house and almost touched the north wall of the "modern" northeast extension. This has been designated the "third well" since two earlier, filled-in wells were also found on lot #55. It was still in use in recent times.

The kitchen stood directly north of the house, its south wall being within about 11 feet of the north wall of the well. The kitchen was built at two or three periods. The earliest part of it was about 20 feet long and 12 feet wide and had a chimney with a fireplace opening 3 x 6 feet at its west side. Fragments of foundation walls to the south and east indicated that the building was extended in these directions at a later date. Another addition of unknown date was a shed 8 feet in depth on the north side of the kitchen. A patch of paving west of the fireplace indicated that the earliest kitchen was brick floored and another south of the south wall was probably the remains of a walk joining the kitchen with the house.

The brick walk, "G", began about 11 feet west of the west wall of the kitchen and extended about 150 feet northward almost to the northern 12 boundary of the lot. This walk was 3½ feet wide and was composed of brick-bats with a few cobblestones interspersed among them. The walk was edged with stretchers.

IV.This group of foundations ("H", "J", and a foundation at the northwest corner, undesignated by letter on the survey map) were all located at the north end of the lot. The foundation at the northwest corner was that of an unidentified building 12 x 16 feet in extent, with an area of packed clay 10 feet square at its east side, which may once have been the floor of the shed. This was probably a service building of the Alexander Craig although, since we are still uncertain of the position of the line between lots #54 and #55, it may have stood on the Raleigh Tavern lot and have been one of the Tavern outbuildings.

Near the center of the lot, along the northern boundary, was an area "H" of a badly-broken brick paving and short stretches of fill indicating the position of a 9-inch brick foundation. In Duke's opinion this may have been the remains of a building about 24 feet long, possibly the Alexander Craig stable.

Foundation "J", at the northeast corner of the lot, consisted of remnants of two 9-inch brick foundation walls forming the northeast corner of an early outbuilding which may have been a coach-house. What the size of this building was is unknown, since the evidence was destroyed by later foundations.

CONDITION OF THE HOUSE BEFORE RESTORATION

The Alexander Craig House before its restoration was a two-story house with a low-pitched (34½°) A-roof with gable ends. The dimensions of the house proper were essentially those of the old foundations, being 51'-7½" (width) x 30'-7" (depth). It had a two-story front porch of late nineteenth-century design on the south (street) elevation. This was not centered 13 on the front facade but, starting about 11'-7" from the west corner of the building, ran 22 feet to a point slightly beyond the line of the east wall of the stairhall. The porch was doubtless placed off-center because of the existence of a shop in the southeast corner of the building. A photograph (see p.1) taken sometime after 1900 shows a glazed door flanked by a glazed fixed panel leading to the room at the southwest corner of the house. This was doubtless at one time the entrance to the shop. Miss Lucy Vaiden in 1940 further confirmed the existence here of a shop in a statement that her grandfather had at one time conducted a store here and had had his "counting room" at the north end of this.

A one-story leanto whose east wall was continuous with the east wall of the house and whose width (19'-5") was the same as that of the "shop" extended to a depth of 20'-2½" to the rear of the back (north side) of the house. Adjoining the leanto to the east was a one-story, enclosed porch 10'-2" in depth and 17'-7¾" in width with three steps leading to the rear yard. A foot-and-a-half to the east of the east side of this porch was a

REAR VIEW OF THE ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE BEFORE ITS RESTORATION SHOWING, AT THE LEFT, THE LEANTO ADDITION AND, AT THE RIGHT, THE BULKHEAD ENCLOSURE. THE PORCH HAS BEEN REMOVED BUT ITS POSITION CAN BE SEEN IN THE MARKINGS ON THE WEATHERBOARDING OF THE HOUSE AND LEANTO.

14

REAR VIEW OF THE ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE BEFORE ITS RESTORATION SHOWING, AT THE LEFT, THE LEANTO ADDITION AND, AT THE RIGHT, THE BULKHEAD ENCLOSURE. THE PORCH HAS BEEN REMOVED BUT ITS POSITION CAN BE SEEN IN THE MARKINGS ON THE WEATHERBOARDING OF THE HOUSE AND LEANTO.

14

THE PHOTO ON THE RIGHT SHOWS THE CONDITION OF THE WEST CHIMNEYS OF THE ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE BEFORE THEIR RESTORATION. THE UPPER PARTS OF BOTH CHIMNEYS HAD BEEN ALTERED AND THEY WERE CONSEQUENTLY REMOVED AND REBUILT (SEE TEXT). THE LEFT-HAND PICTURE SHOWS THE NORTH CHIMNEY THE OUTLINE OF THE WOOD CLOSET LEANTO WHICH ONCE EXISTED BETWEEM THE TWO CHIMNEYS. THIS EVIDENCE WAS THE BASIS FOR THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE LEANTO.

roofed bulkhead 6'-6" wide, 4'-10" deep and 5'-0" high enclosing an outside basement stair. The west wall of the house had a brace of chimneys serving two fireplaces on the first and two fireplaces on the second floor of the house. (See p.13) These chimneys were slightly different in height, the south chimney rising about three inches higher than the north to a point 3'-2" above the comb of the roof. These chimneys were different in width and depth; their set-backs were different in character and at different levels; and both stood free of the house, but at different

15

points in their height, the south chimney becoming detached from the house at the point 6'-8" above the finished second floor line and the north chimney at a level of 13'-2" above the second floor line. The brickwork of the south chimney was old to a point 11'-0" above the finished first floor lone and that of the north chimney to a height of 9'-8" above the first floor, while the brickwork above was of later date. When, on being restored, the house was cut-down to a story-and-a-half, this old brickwork was retained and the later portions replaced by new chimneys of different design above the points where the old brickwork terminated. The field architects also found indications in the old brickwork of the south chimney of the previous existence of a shed 2'-8" in depth extending from chimney to chimney. The inclined roof of the shed rose to a height 8'-8" above the finished first floor of the building. This formed the basis for the building of the weather-boarded shed in the restored house.

THE PHOTO ON THE RIGHT SHOWS THE CONDITION OF THE WEST CHIMNEYS OF THE ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE BEFORE THEIR RESTORATION. THE UPPER PARTS OF BOTH CHIMNEYS HAD BEEN ALTERED AND THEY WERE CONSEQUENTLY REMOVED AND REBUILT (SEE TEXT). THE LEFT-HAND PICTURE SHOWS THE NORTH CHIMNEY THE OUTLINE OF THE WOOD CLOSET LEANTO WHICH ONCE EXISTED BETWEEM THE TWO CHIMNEYS. THIS EVIDENCE WAS THE BASIS FOR THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE LEANTO.

roofed bulkhead 6'-6" wide, 4'-10" deep and 5'-0" high enclosing an outside basement stair. The west wall of the house had a brace of chimneys serving two fireplaces on the first and two fireplaces on the second floor of the house. (See p.13) These chimneys were slightly different in height, the south chimney rising about three inches higher than the north to a point 3'-2" above the comb of the roof. These chimneys were different in width and depth; their set-backs were different in character and at different levels; and both stood free of the house, but at different

15

points in their height, the south chimney becoming detached from the house at the point 6'-8" above the finished second floor line and the north chimney at a level of 13'-2" above the second floor line. The brickwork of the south chimney was old to a point 11'-0" above the finished first floor lone and that of the north chimney to a height of 9'-8" above the first floor, while the brickwork above was of later date. When, on being restored, the house was cut-down to a story-and-a-half, this old brickwork was retained and the later portions replaced by new chimneys of different design above the points where the old brickwork terminated. The field architects also found indications in the old brickwork of the south chimney of the previous existence of a shed 2'-8" in depth extending from chimney to chimney. The inclined roof of the shed rose to a height 8'-8" above the finished first floor of the building. This formed the basis for the building of the weather-boarded shed in the restored house.

ANALYSIS OF THE HOUSE PLAN

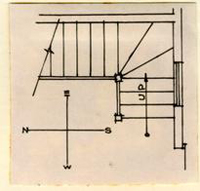

The plan of the first floor of the reconstructed Craig House follows in general the foundation plan but many changes have been made in what must have been the original positions of the partitions in order to accommodate the interior to the uses of modern living. The plan of the first floor of the house is a plan with a central hall flanked on either side by a pair of rooms. The two east rooms now serve as dining room and kitchen, the two west rooms as living room and bedroom. Between the kitchen and the rear hall are a storeroom and pantry and the kitchen has a recessed cabinet on its south side and a door to the outside in its north wall. Between the bedroom and the rear hallway are a bathroom, and a clothes closet 17 accessible from a vestibule leading to the bedroom. The dining room has a corner fireplace at the northeast corner of the room and the living room and bedroom each has a fireplace approximately centered on its west wall. The hallway is divided by a pair of archways into two parts, a 12-foot wide front hall and a 10'-6" wide rear hallway. The front door of the house is located about a foot east of the west wall of the front hallway, and two feet to the right of the door opening starts a "mixed" stairway, consisting of a short flight of three treads moving eastward, followed by a right-angle turn of three winders, followed in its turn by a straight run of six risers against the east wall of the hallway. A cellar stair begins in the northeast corner of the front hallway and runs under the main stair to the basement. The rear hall has a doorway located about a foot east of the west wall of the hallway. Because of the reduction of width of the hallway at the rear the front and rear doors are not lined up with each other. A second front entrance, a 4-foot door of two valves, is located at the center of the north wall of the dining room. This represents the entrance to the old shop.

The second floor of the house has two bedrooms, one on either side of the center hallway. The west bedroom has a fireplace in its west wall and the east bedroom a corner fireplace in the northeast corner. Each bedroom has a pair of dormers in front and a single dormer at the rear and a line of closets extending across the entire rear wall except for the space occupied by the dormers. The hallway is lighted by a rear dormer window flanked by a pair of closets. A bathroom lighted by a dormer window occupies the space between the stairway and the west wall in the front half of the stairhall.

18Because of the modern features incorporated in the plan only two partitions of the first floor stand above the original foundations of the house (see archaeological plan, p.6), viz., the north-south partition separating the dining room and kitchen area from the hallway, and the east-west partition line (interrupted by openings in the hallway, kitchen and pantry) separating the living room from the bedroom, the front from the rear hall and the dining room from the kitchen area. The north-south partition stands above the west wall of Wagnon's shop and its extension, the "northeast" room. The transverse partition line follows fairly closely the foundation line below, which, as has before been noted, is a broken one. The partition between the living room and bedroom rests directly on the foundation between the southwest and north-west rooms, which is a continuous one, but extends about 5 feet beyond this to the east. The rear arch of the two archways in the hall and the rear wall of the hallway closet are directly above the two piers which constitute the continuation of this foundation line between the "south central" and "north central" rooms. The previously-mentioned pier and wing wall extension of the chimney foundation between the "northeast" and "southeast rooms" lie about 6" to the south of the foundation line in the spaces to the west, so that the partition line at the south wall of the kitchen above falls slightly to the north of them.

The chimney of the dining room is a new chimney, built, however, directly above the old foundations while the chimneys of the bedroom and living room are the old chimneys with new fireplace openings.

The dimensions of the plan are as follows: length, 51'-6", width 30'-7".

DETAILED DISCUSSION OF EXTERIOR

BRICKWORK

The brickwork used in the construction of the house is found in the following features:

- a.Foundations, which include the foundations of the house walls, the chimneys, the porches and the bulkhead.

- b.The three chimneys.

- c.The base-of-the wall gutters at the front and rear of the house.

- d.The hearths of the five fireplaces.

All of this brickwork is new except for a part of the brickwork of each of the two west chimney stacks which is old. The new brick were made in a kiln in Williamsburg using the same materials and methods employed in brickmaking in the 18th century, in an attempt to give the brick, as far as possible, the quality and appearance of colonial brick.

The mortar found in the old brickwork is oyster shell lime mortar and the same type of mortar was also used in laying up the new brickwork. In the case of both old and new brickwork the joints are tooled.

Brick Color

The remaining old brickwork of the house, i.e., the old brickwork of the two west chimneys, was covered with gray paint when the restoration of the building was started. This gray color was left on the old brickwork whereas the new bases and tops of the chimneys were left unpainted.

The new brickwork varies considerably in color. The color ranges from a light salmon to a deep salmon buff. There are a few dark 20 toned and completely glazed headers. No rubbed brick have been used on the house.

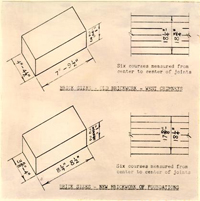

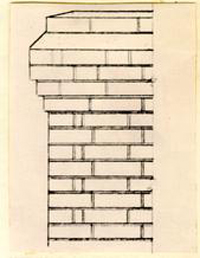

Brick Sizes

The diagrams below give the average sizes of the brick found, first, in the old parts of the west chimneys and second, in the new masonry of the foundation walls. The sizes shown were obtained from measurements made on the job and in each case they are a summary of several measurements made at different points.

Foundations

The foundations are new throughout. The old foundations (see archaeological drawing, p. 6 and photo, p. 7) were in such poor condition that it was considered unwise to attempt to retain them.

The new foundation walls of the house proper are of concrete below grade and of reproduced brick above. The concrete walls rest on concrete footings. The porch foundations are of brick below as well as above ground, and they are without footings.

The bond of the house foundations is partly English and partly Flemish. To aid in making it appear that the east or "shop" portion of the house is the older part, its foundations (on the south, east and north elevations) have been laid in English bond, the type generally used in the older colonial foundations. Under the remainder of the front elevation and on the west side elevation, from the southwest corner to the south chimney, Flemish bond, a type which, when used in foundations, generally represents later colonial brickwork, has been used. There are, it seems, however, certain inconsistencies in the use of the two types of foundation brickwork to express differences in age in the several parts of the house, for English bond (again, the older type) was used on the north elevation under the northwest portion of the house, which is believed to be later. English bond was also used under the west closet leanto, which is either the same age as the west wall (which is partly Flemish bond) or later. To be consistent these later features should have had foundation walls in Flemish bond.

Chimneys

Two free-standing chimneys, the pair on the west side of the house, were in existence when the restoration of the house was begun. 22 The foundation of a third chimney (on the east side) was likewise found but the chimney itself was no longer in place. (See photo, p. 7).

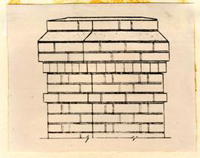

The west chimneys were in large part old though their upper portions had been rebuilt, probably at the time the house was altered from a 1½-story to a 2-story building. (See photographs and description of west chimneys as they existed prior to the restoration of the house, pp. 14 and 15). These chimneys were restored, the upper part of the shafts and the caps being rebuilt in accordance with the spirit of 18th century chimney design. The chimney cap of the north chimney, the smaller of the two, consists only of three projecting courses of brickwork, a chimney cap design which was found on a chimney of Wynne, a house in the vicinity of Carter's Grove in James City County. The cap of the south chimney is more elaborate in its design, having three projecting bands of brickwork, of which the third or top band is made up of a double brick course. A sloping cement wash above this terminates in a final single-course band which lines up with the brickwork of the chimney shaft. The design of this chimney shaft follows closely that of the chimney of the small building known as "Casey's Gift" which once stood in Williamsburg.

ONE-HALF OF WEST ELEVATION OF RECONSTRUCTED CAP OF SOUTH CHIMNEY OF WEST SIDE. THIS FOLLOWS DESIGN OF CASEY'S GIFT CHIMNEY CAP.

ONE-HALF OF WEST ELEVATION OF RECONSTRUCTED CAP OF SOUTH CHIMNEY OF WEST SIDE. THIS FOLLOWS DESIGN OF CASEY'S GIFT CHIMNEY CAP.

Drawing of Chimney Cap

Before closing the subjects on the west chimneys it should be noted that though they are preponderantly of old brickwork which was not taken down and relaid, they were nevertheless raised bodily about 1'-6". They were underpinned, raised and placed upon new brick foundations. This was done in

22a

Paired chimneys of the type found in the Alexander Craig House are fairly common in old Virginia houses. The photo at the left (the Pendleton House, Caroline County) shows such a "brace" of chimneys, with a wood leanto between.

Paired chimneys of the type found in the Alexander Craig House are fairly common in old Virginia houses. The photo at the left (the Pendleton House, Caroline County) shows such a "brace" of chimneys, with a wood leanto between.

Photograph of the Pendleton House

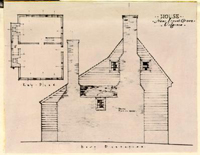

The drawing below shows the plan and side elevation of a house near Locust Grove, King and Queen County, which has a brace of chimneys consisting, like the Alexander Craig example, of one larger and one smaller stack. The closet leanto, unlike that of the Craig house, is of brick in this case.

The drawing below shows the plan and side elevation of a house near Locust Grove, King and Queen County, which has a brace of chimneys consisting, like the Alexander Craig example, of one larger and one smaller stack. The closet leanto, unlike that of the Craig house, is of brick in this case.

Drawing of House Near Locust Grove

23

consequence of the raising of the level of Duke of Gloucester Street about 1½ feet at this eastern and in order to bring it to its former colonial level. The entire house, in fact, was raised in order to restore the floors to what was believed to have been their colonial level and the chimneys were necessarily raised at the same time so that the fireplace hearths would be level with the floors. The present height of the first floor is approximately 2'-4½" above the restored colonial grade. One less fortunate consequence of the raising of the floor levels is the elevation of the front cornice of the Alexander Craig House above that of the Scrivener House, which nearly touches it on the east. The floor levels of the Scrivener House were not raised as were those of the Alexander Craig House.

The east chimney, a T-shaped chimney built within the east wall of the house, is, in its entirety, reconstructed. It serves a corner fireplace in the northeast corner of the southeast room of the first floor and a similar though smaller corner fireplace in the bedroom directly above, and it also houses the boiler flue. It is located on the site of the old east chimney foundation which still existed when the reconstruction of the house was begun. (See photo of old basement foundations, p.7 and plan of excavated foundations, p.6.)

The necessity of caring for three flues would not in itself have justified the use of the T shape, since these could have been incorporated in a rectangular stack. The stack was given its T shape (a 17th century chimney form which persisted into the next century) to emphasize the fact that the east portion of the house was originally older than the west portion.

The chimney cap (see illustration on next page) has beneath its double projecting band an interesting feature, viz., a course of

24

CAP OF T-SHAPED CHIMNEY OF ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE SHOWING BRICK COURSE LAID IN "DOG-TOOTH" PATTERN (BRICK "COGGING").

CAP OF T-SHAPED CHIMNEY OF ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE SHOWING BRICK COURSE LAID IN "DOG-TOOTH" PATTERN (BRICK "COGGING").

Drawing of Craig House Chimney

brick laid diagonally, which lends vivacity to the cap through its pattern of alternating rectangles of light and shadow. This motif is known as a "dog-tooth" pattern or "cogging"* brick, as it was called in the 18th century. An old Virginia chimney the cap of which has cogged brickwork is a chimney of Warburton Place in James City County. In this case there are two rows of cogging beneath a triple-coursed projecting band of brickwork.

Brick Paving

The rather extensive areas of old brick paving which were uncovered on the Alexander Craig plot in the course of the excavations conducted there have already been discussed—see text, pp. 5 and 11, archaeological plan, p.6 and photo, p.8. None of this old brick paving has been retained.

Aside from fireplace hearths, no brick paving has been used inside of the reconstructed house. A large service area directly behind the 25 house has, however, been paved with reproduced colonial brick in "basket" pattern and in the garden areas at the west and north (rear) of the house a network of brick walks has been laid in running bond. The central walk of the series at the back leads directly from the service area to the gravel-covered stable yard at the rear of the lot. For the layout of the paved areas on the Alexander Craig plot the reader should consult landscape drawing, L3.

Brick Ground-level Gutters

Remnants of brick ground-level gutters or drips were found along the north foundation wall of the house between the center line of the building and the northeast corner. It was assumed from this that the house, like several others in Williamsburg, had these surface gutters adjacent to the foundation walls to receive the rain water from the roof. Such drains prevent the water from pitting the ground surface next to the building and seeping down into the foundations and thence into the basement. Surface gutters of this type have, therefore, been placed about the Alexander Craig House at the points where they are needed, viz., on the north and south sides beneath the eaves. These gutters are necessarily interrupted at the points where stoops and the bulkhead occur. At each side of the house the gutters are pitched toward drains, through which the rain water is carried into gutter drain piping emptying into the house sewer.

Brick Hearths

See mantel schedules for a description of the hearths.

STONEWORK

The stonework used in the house is confined to the three stone steps at the main entrance. These are solid rectangular blocks of Indiana limestone (a substitute for the Purbeck or Portland stone used in colonial

26

PROFILE OF STONE NOSING OF FRONT ENTRANCE STEPS.

times) with molded nosings cut to the profile shown in the adjacent sketch. This nosing profile is similar to a number of stone step nosings found in old Virginia houses. As examples, the nosing profiles of the stone steps of Carter's Grove, James City County; Westover, Charles City County and Blandfield, Essex County may be mentioned, as well as those of the President's House and the John Blair House in Williamsburg. The steps of the latter are said to have formed originally the entrance stoop to the first Williamsburg theater, which was located on the Palace Green.

PROFILE OF STONE NOSING OF FRONT ENTRANCE STEPS.

times) with molded nosings cut to the profile shown in the adjacent sketch. This nosing profile is similar to a number of stone step nosings found in old Virginia houses. As examples, the nosing profiles of the stone steps of Carter's Grove, James City County; Westover, Charles City County and Blandfield, Essex County may be mentioned, as well as those of the President's House and the John Blair House in Williamsburg. The steps of the latter are said to have formed originally the entrance stoop to the first Williamsburg theater, which was located on the Palace Green.

WALLS

The Alexander Craig House is a wood-framed building, covered on the exterior with weatherboarding on all faces except the east part of the north front (the portion which represents the old shop) which has flush beaded boarding. The framing and exterior covering are new throughout.

At the time the reconstruction of the building was begun, the building was, of course, a two-story structure. Naturally, it had to be cut down to make of it a story-and-a-half house, the type it had been before a second full story was added to it sometime in the 19th century.

The old wood frame

Among the progress photographs made during the course of the demolition of the existing house are several views showing the framing

27

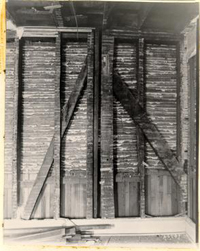

OLD NORTH WALL FRAMING OF SOUTHWEST ROOM SHOWING CLEAVAGE IN STUDDING WHICH INDICATED TWO DISTINCT PERIODS OF CONSTRUCTION.

of the first floor. (This timberwork, by the way, was considered insecure, and it was therefore replaced by new framing.) A study of the old framing revealed certain important facts which, in general, supported the thesis derived from a study of the foundations that the building was built at different periods, and it also aided in establishing the locations of the openings of the 18th century structure. One view (progress photo N6598) a photo made in the hallway, clearly shows a joint between the framing of what the foundation evidence indicated at the old east portion and the addition to the west. Progress photo N6597 (shown above) reveals a distinct cleavage in the vertical framing of the north wall of the southwest room. Another photo (see next page), a view of the west wall of the same room, bears witness to the fact that there were no windows in that room (the studding is unbroken by notches which if they existed, would signify that the horizontal members of the window framer had at one time been inserted in the wall.) Progress photo N6601 (see next page), a shot of the southeast

28

OLD NORTH WALL FRAMING OF SOUTHWEST ROOM SHOWING CLEAVAGE IN STUDDING WHICH INDICATED TWO DISTINCT PERIODS OF CONSTRUCTION.

of the first floor. (This timberwork, by the way, was considered insecure, and it was therefore replaced by new framing.) A study of the old framing revealed certain important facts which, in general, supported the thesis derived from a study of the foundations that the building was built at different periods, and it also aided in establishing the locations of the openings of the 18th century structure. One view (progress photo N6598) a photo made in the hallway, clearly shows a joint between the framing of what the foundation evidence indicated at the old east portion and the addition to the west. Progress photo N6597 (shown above) reveals a distinct cleavage in the vertical framing of the north wall of the southwest room. Another photo (see next page), a view of the west wall of the same room, bears witness to the fact that there were no windows in that room (the studding is unbroken by notches which if they existed, would signify that the horizontal members of the window framer had at one time been inserted in the wall.) Progress photo N6601 (see next page), a shot of the southeast

28

OLD WEST WALL OF SOUTHWEST ROOM BEFORE ITS DEMOLITION. NO NOTCHES, SUCH AS THOSE WHICH WOULD BE LEFT AFTER THE REMOVAL OF WINDOWS, ARE VISIBLE IN THE STUDDING, INDICATING THAT THIS WALL NEVER HAD ANY OPENINGS IN IT.

OLD WEST WALL OF SOUTHWEST ROOM BEFORE ITS DEMOLITION. NO NOTCHES, SUCH AS THOSE WHICH WOULD BE LEFT AFTER THE REMOVAL OF WINDOWS, ARE VISIBLE IN THE STUDDING, INDICATING THAT THIS WALL NEVER HAD ANY OPENINGS IN IT.

OLD FRAMING OF SOUTHEAST ROOM, LOOKING SOUTHEAST. NOTCH, INDICATED BY ARROW, GAVE CLUE TO LOCATION OF OLD SHOP DOOR.

29

room, shows at the upper right a notch in a stud which once received the door head. The framing of the east wall offered proof, since no notching was discovered, that no window existed in that wall in the 18th century (the east window shown in the picture was a late intruder).

OLD FRAMING OF SOUTHEAST ROOM, LOOKING SOUTHEAST. NOTCH, INDICATED BY ARROW, GAVE CLUE TO LOCATION OF OLD SHOP DOOR.

29

room, shows at the upper right a notch in a stud which once received the door head. The framing of the east wall offered proof, since no notching was discovered, that no window existed in that wall in the 18th century (the east window shown in the picture was a late intruder).

The walls as reconstructed

The walls of the reconstructed house, both exterior and interior, are new throughout, as was stated above. Since the framework is wholly concealed, present-day framing methods have been used in their reconstruction. Except for certain sheathed walls, which are discussed in the section of the report dealing with the details of the interior, the interior walls and the inside faces of the exterior walls are plastered in the modern manner, using three costs of commercial plaster over metal lath.

The outside faces of the exterior walls, as has been remarked, are covered for the most part with beaded weatherboarding of heart cypress. The weatherboards have been given an exposure of from 5-¾" to 6". The boards are face-nailed with hammered-headed wrought iron nails. The bead at the bottom of these boards which are at the window sill level, have been made to line up with the beaded lower edge of the sills.

The one-time shop front (the east part of the south facade) has been rendered distinct from the remainder of the street face of the house by being covered with random-width, flush, beaded boarding, applied horizontally. There was a good basis for this, since the remodeled two-story house at the time (sometime after 1900) when the photo on p. 1 of this report was taken, had similar flush boarding on the front face of the shop portion. It was assumed that this disparity in the treatment of the two parts of the front facade of the building had also obtained in colonial times and had been maintained down through the 19th century.

EXTERIOR TRIM

All of the trim and other wood features of the Alexander Craig House are, of course, new. Since the building, by the time it passed into the hands of Colonial Williamsburg, Inc. had been much altered from its 18th-century condition, the detailing, for the most part, is not copied after parts which existed on or in the building but is based upon authentic 18th-century examples found in Williamsburg and elsewhere in Tidewater Virginia.

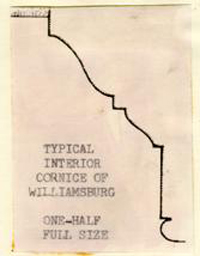

Main cornice, street facade

The main cornice (south front) consists of two elements, viz., that part (roughly two-thirds of the front elevation) which is found on the house proper, and the remainder which runs along the eaves of the roof over the shop portion. Again, to aid in making it appear that the shop was built at a different period from the part of the building to the west of it, the shop cornice has been given modillion blocks, while the remainder of the front facade has none. Actually, no clue to what the 18th century cornice was could be gained from an examination of the photo of the two story house (p.1) or from a study of the documents relating to the property.

House cornice

The cornice of the house proper was designed, therefore, as a typical 18th century modillionless cornice, which has been used on many restored and reconstructed buildings in Williamsburg. It consists of a crown mold, fascia, projecting soffit and a base mold superimposed upon a fascia which overlaps the top weatherboard. It is similar to such old examples found in Williamsburg as the main cornice of the Travis House and the front and rear cornices of Casey's Gift (now demolished).

Shop cornice

The cornice of the shop is, except in the respect that block modillions are fixed to the overhanging soffit, similar to the neighboring "plain" cornice. The sequence of molding is, except for the inclusion of the blocks, much the same in both cases. The modillions are simple rectangular blocks of wood surmounted by a cyma reversa or ogee molding. The blocks are spaced about 1'-1 3/8" on centers. Old modillion cornices which may be considered precedent for that of the Alexander Craig House are the front and rear cornices of the Lightfoot House in Williamsburg and the main cornice of Wales, Dinwiddie County.

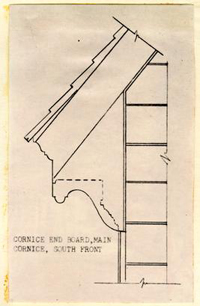

Cornice end board

Cornice end board, main cornice, south front

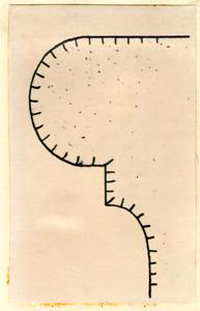

Cornice end board, main cornice, south front

The cornice of the shop and that of the house proper are separated from each other by a cornice end board similar to the cornice stops used at either end of the south façade of the building. These cornice end boards (illustrated at left) have no direct precedent. The main curve is, in a general way, similar to that of the old end board at the southwest corner of the Travis House in Williamsburg. The other 32 details of which the cornice stop is composed are taken from cornice end boards found in the Virginia Tidewater area. It is likely that no single old cornice stop could be found which would be exactly like this one. In fact it is probable that such features were varied endlessly in the 18th century and that no two were designed precisely alike.

Rear cornice and cornice end board

The rear cornice is modillionless and it is similar to the modillionless cornice of the main front except that it is a somewhat reduced version of the latter. The soffit of the rear cornice, in particular, has a much smaller projection than that of the main cornice. The cornice end board is also much simpler than that of the south cornice and follows much more closely the profile of its cornice than does the example on the front.

Corner boards

The corner boards, which act as stops for the weatherboarding, are of the single-faced type, with their narrow sides placed at the ends of the house. All of them are 1¼" thick and they all have a ½" bead at the exposed corner. The boards are 3½" wide on all corners of the house except the southeast (shop) corner, where the corner board, which receives both the flush boarding of the shop front and the weatherboarding of the east face of the shop, is 5½" wide.

One additional corner board has been applied to the north front, viz., the "vestigial" corner board which has been placed at the junction of the shop front with the main face of the house proper. A stop was necessary here to effect a transition between the two different types of facing boards. This vestigial corner board is of the 33 same type and size as the end board of the southeast corner of the shop. This feature, again, serves to suggest that the oldest part of the building, the shop, at one time terminated at this point. Logically enough, it is beaded on one edge only and this edge has been turned toward the west (the west corner of the shop when this existed alone.)

Rakeboards

The rake- or barge boards, which on the gable ends of the house follow the slope of the roof and, overlapping the weatherboards, serve to effect a transition between the latter and the roof covering, are flat boards, beaded on the lower edge. On the steeper slope of the south side of the gable they start with a width at the bottom of about 5½" and move with a gradual taper toward the ridge. On the back (north) side they are about 5" wide at the base and also taper as they move upward, but the narrowing down of the boards is "slower" due to the fact that the length of the roof incline is so much greater at the rear.

ROOF

The reconstructed roof of the Alexander Craig House is a mixed type—it may correctly be called a modified "A" roof. It has a normal front slope of about 50 ¾°. This slope starts at the top at the roof ridge, which is centered on the south chimney of the west side and consequently also on the longitudinal center line of the southwest room. The rear slope (about 28°) is much lower than the front slope and it is continuous from the ridge to the rear (north) eaves of the house. Extensions of this roof, continue down at an angle of about 19° to form the roofs of the main rear entrance porch and the kitchen porch. The rear part of the roof is much wider (deeper) than the front part, since the roof ridge, due to its location over the center line of the southwest room, is several feet south of the longitudinal center line of the 34 house taken as a whole.

The main roof of the house, the porch and leanto roofs and the dormer roofs, as well, are covered with round-butted asbestos cement shingles. These shingles have been used on most of the other restored and reconstructed buildings in Williamsburg. They resemble wood shingles in texture, and weather to a color which suggests that of weathered wood shingles. They are used in lieu of wood shingles because they are fireproof. Round-butted shingles were used frequently in the 18th century. They have this advantage over square-butted shingles, that their rounded ends make it easier to align them and to keep them in alignment than is the case with shingles which have straight lower edges.

The basis for the design of the roof

No documentary evidence was found to aid in the determination of the shape of the original roof. The roof which was placed on the house was given the shape which certain archaeological evidence and a consideration of the nature of 18th century roofs in the Tidewater Virginia area in general seemed to indicate as the most likely type. Francis Duke, in his archaeological report on the Alexander Craig (Vaiden) House site (August, 1941), presents a fair summary of the reasons which led the architects to give the roof the form which it has at present:

Second floor joists in the south half of the building were sawn off flush with the studs at their south ends, no doubt when the second floor wall was built. These joists at their north ends have their original projection beyond the plate of the center partition, originally the north exterior wall. [See photograph on next page.]35

VIEW OF FRAMING OF OLD SECOND FLOOR JOISTS IN NORTH OR SHED PORTION OF BUILDING BEFORE ITS RECONSTRUCTION. THE PROJECTING ENDS OF THE JOISTS OF THE SOUTH PORTION ARE BELIEVED TO HAVE RECEIVED THE REAR CORNICE OF THE ORIGINAL 1½-STORY STRUCTURE AT THE TIME THIS WAS A ONE-ROOM-DEEP HOUSE.

VIEW OF FRAMING OF OLD SECOND FLOOR JOISTS IN NORTH OR SHED PORTION OF BUILDING BEFORE ITS RECONSTRUCTION. THE PROJECTING ENDS OF THE JOISTS OF THE SOUTH PORTION ARE BELIEVED TO HAVE RECEIVED THE REAR CORNICE OF THE ORIGINAL 1½-STORY STRUCTURE AT THE TIME THIS WAS A ONE-ROOM-DEEP HOUSE.

Evidence for the slope of the original roof is scanty but appears definite. It is clear from the location of the chimneys that the earliest roof must have been of 'A' section rather than hipped (unless it was a gambrel, and there is no evidence that it was). When the north rooms were added, they may be presumed to have had a shed roof. (The only alternative would seem to be gables facing north; but this is highly improbable, for the chimneys are not located where they could have heated the gable rooms).

The probable height of the north cornice can be fixed with reasonable accuracy by the second-floor joists. The first slope tried for the shed roof was based on the assumption that it might have joined the north slope of the original front roof at a level just below the dormer sills. But it was found that such a slope for the shed roof would be of less than 13 degrees. Such slopes in the XVIII century were rarely less than 25 degrees. This system of construction is therefore highly improbably in itself.

36But there is ulterior evidence against also. The northwest chimney, which was of early brickwork up to a level just below the second floor, must have had somewhere above this level the usual sloping brick shoulders, which extended up to a small brick ridge on the house side, where the chimney came clear of the building. This brick ridge must always clear the flashing problem. But no matter how low the shoulders and brick ridge might have occurred, within the known limit, the roof line of the shed (as assumed above) would cut too low.

These two objections to the low slope of the shed roof are so strong as to seem conclusive. The likeliest alternative is that the rear slope was continuous from the early ridge to the new north cornice. This slope is of more than 27 degrees, and provides wider head-room inside, while dormer may still be used.

Roofs of this type are not uncommon. Some other examples are the Repiton and Moody houses (with front slope as for A roof), and the Prentis and Travis houses (with front slope as for Gambrel roof).

To this analysis of Mr. Duke's should be added the supposition that, when the north addition was made to the early one-room deep house, the entire rear part of the roof must have been rebuilt. This is likely since, with the ridge line centered on the longitudinal axis of the early building, the north slope would undoubtedly have been the same as the south. At present, as was remarked above, the rear slope is about 28° while the front slope is much steeper (ca. 50 ¾°).

DORMERS

There are, in all, on the house, eight dormers—five on the front roof slope and tree on the rear. These are alike in design, front and rear, all being of the gable-ended type and all housing 15-light windows (3 lights wide and 5 high).

There was no documentary or other basis for the number, positions, or design of the dormers. They were placed at those points of 37 the roof where they would be most useful is bringing light to the spaces of the second story. Thus, each of the two bedrooms was given two dormers on the south side, spaced nearly, if not quite, symmetrically about the transverse center lines of these rooms. Each bedroom was also given a rear dormer, located between the closets which, except for the space occupied by the dormers, form an unbroken line across the back wall of the second floor. These rear dormers are not quite centered on the north-south axis of the bedrooms. A center dormer lights the bathroom on the south side and another on the north performs the same service for the second floor hallway.

Externally, the dormers are not placed with exact symmetry in respect to the north and south façades, but the spacing between them is sufficiently regular to present the appearance of symmetry. On the south front only the two west dormers line up with the windows below them. Due to the circumstance, occasioned by the fact that the shop occupies the east portion of the building, that it was impossible to achieve symmetry on the first floor facade, the remaining quasi-symmetrical dormer windows do not line up with any of the openings below them, although they are, nevertheless, in an ordered relation to the first floor windows and doors.

On the north façade it was possible so to dispose the three dormers in relation to the doors and windows of the first floor that the east and center dormers fall directly above the kitchen and rear entrance doorways respectively. The third (west) dormer lies about midway between the two westerly windows below it.

The dormers have, as was noted above, gable ends, the sloping sides of which are trimmed with tapering rakeboards. The lower edges of these are beaded and their bottom ends are cut off straight. The gables 38 are covered with random-width flush boarding, unbeaded. The sides of the rakeboards, as is typical of 18th century dormers in Williamsburg, are covered with random-width beaded boarding. In the case of both the front and rear dormers the boarding follows the incline of the roof slope on which the dormers are located. It is worthy of mention that in side view the dormers of the rear have an aspect different from those of the front—they are, due to the much lower incline of the rear (north) roof slope much longer than those of the front.

The dormer roofs have, uniformly, a slop of about 47½° so that their inclination is unlike both the front slope of the main roof (ca. 50 ¾°) and the rear slope (ca. 28°). The roof covering of the dormers is, like that of the main roof, round-butted asbestos shingles.

The dormer sills are of the square-cut type, the ends of which line up with the outside edges of the vertical elements of the window trim.

The dormer design, described above, was based upon characteristic 18th century examples found in Williamsburg and its locality. The old dormers of the Bracken House and Casey's Gift (now demolished) in Williamsburg are of the same type and have the same detailing as those of the Alexander Craig House. In the first example the windows also have 15 lights.

PORCHES AND STOOPS

Main Front Entrance Stoop

The three stone steps which are the main feature of the stoop have already been discussed at some length on pp. 25 and 26. It should be added that the steps are supported on brickwork, which is exposed to view at the sides of the stoop.

39The stoop has a wrought iron railing at either side, the handrail of which is rounded at the top. This is 1-1/8" in width and about 7/16" in thickness. The rail is fastened against the weatherboarding of the house and descends the steps without turning, to be arrested at the bottom by a tapering newel with champfered sides, whose base is square in section—1-1/8" on each side. This newel is terminated at the top by a turned brass finial. Four additional balusters or posts aid in the support of each railing. These are flat bands of wrought iron, turned flatwise to the house front. These are ¾" on the flat side and 3/8" in thickness. Both the newels and the balusters are secured in place by being set in lead in 3" deep slots in the stone steps.

Wrought iron railings of this simple type are easily made by a blacksmith so that they were in frequent use in 18th century Virginia. The handrailing of the stone steps on the north side of the President's House of the College of William and Mary is an old example of the same general type as the reproduced handrail of the Alexander Craig House. The railing of the President's House is longer and slightly different in design (it turns at the bottom) but the elements of which it is composed are similar to those of the Craig railing.

Entrance Steps to Shop

These steps are of wood and are of simple design. They consist of three wood steps, the treads and risers of which are mortised and tenoned into 2" thick stringers at either side. The top edges and the outside lower edge of these stringers are provided with a ½" bead. A central carriage (a wood support with cut-outs to receive the treads and risers) aids in supporting the steps. The steps are open beneath the stringers.

40Steps of this same character (though without risers) are to be seen in pictures of old houses in a collection of photographs taken during the Civil War. This collection may be consulted in the Colonial Williamsburg Department of Architecture.

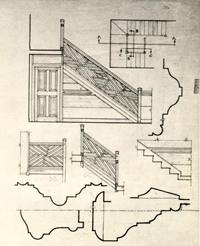

Rear Hall Porch and Kitchen Porch

The covered porch at the rear entrance to the hall (see illustration), like the stoop at the front, is placed over the site of colonial foundations. The design of this porch was based upon that of other 18th century porches of Williamsburg and its vicinity.

NORTH FACE OF ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE SHOWING THE TWO REAR PORCHES

NORTH FACE OF ALEXANDER CRAIG HOUSE SHOWING THE TWO REAR PORCHES

The kitchen porch, which was placed at the east side of the north front to serve the kitchen entrance, is, in all of its detailing, very much like the rear hall porch, so that the details of these two porches will be discussed together.

Both porches, as was indicated earlier (p.33), have shed roofs which continue the north slop of the main roof, though this continuity of surface is broken by a change of inclination. (The main roof slope is 28°, while that of the rear porches is about 19°).

The two porches (without the steps) are almost identical in size, both being about 6' wide and 5' deep. Both are supported by two columns and two half columns applied to the face of the building. These columns and half columns are turned above the railing level and taper toward the top. The railing-high bases of the columns are square in section.

Each porch has 6 steps (i.e., 6 risers). In the case of the rear hall porch these run straight down from the porch platform. The kitchen porch is turned sidewise, with 3 risers descending to an intermediate landing. Three risers at right angles to these lead from the landing to the ground.

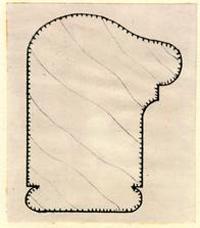

The railings of the porches are, in detail, exactly alike. On the porch platforms these are supported by the square-sectioned bases of the columns and half columns. the handrail (see sketch on following page) is one-sided—that is, it has the normal molded profile which serves as a grip for the fingers on one side (the outside) only. This railing also descends the steps, to terminate in a square-sectioned newel with a molded top.

42

SECTION THROUGH HANDRAIL OF THE TWO REAR PORCHES.

SECTION THROUGH HANDRAIL OF THE TWO REAR PORCHES.

In lieu of the balusters, the sections of both handrails which are on the porch platforms have "panels" of random-width beaded boarding. The top of these panels are mortised into the underside of the handrail and the bottom, which is 4" above the porch floor, has both edges beaded.

The rails which descend the steps are open, each having, below the handrail, two boards (about 6½" high and 1" thick) which are beaded top and bottom and which parallel the inclination of the handrail.

The porch platforms, of wood, are supported on brick foundations, while the steps are open beneath and rest on the paving of the kitchen court. The triangular sides of the roof "canopies" are faced with random-width beaded boarding and the transition between this boarding and the roof covering (round-butted asbestos-cement shingles) is effected by means of a tapering rakeboard, beaded at the bottom and cut at the lower end to follow the profile of the crown mold which runs across the north face of the porch at the eaves.

Precedent for the Detailing of the Rear Porches

Covered porches were a not infrequent adjunct of the 18th century houses in America. James Thacker, a traveller here, writing in 1778, speaks as follows of them:

There is a peculiar neatness in the appearance of their dwellings, having an airy piazza supported by pillers in front.43

In his book, The City and Country Builder's and Workman's Treasury of Designs (London, 1741), Batty Langley, a prolific writer of builders' handbooks, gives the primary reason for the construction of hoods and porches, such as those of the Alexander Craig House, at entrance doorways:

It also very often happens, that even when Frontispieces [doorways] may be finished with Pediments [hoods], that the Projection of the Pediment will not be sufficient to protect the Entrance from the Insults of Rains; therefore in such Cases, the Pediments must advance forward, and be sustain'd either by Trusses [brackets] ... or by Pilasters, or Columns ....

The most conspicuous feature of the two rear entrance porches, the turned columns, have ample precedent in 18th century Virginia houses. A local example, the columns of the western entrance porch on the south side of the Coke-Garrett House, is an excellent one to cite, since the two full columns and the two half columns applied against the weatherboarding of the house are very similar in character to the reconstructed columns of the Alexander Craig porches. The Coke-Garrett columns are square in section up to a point slightly above the handrail, which they receive. Above this point the columns are turned and they diminish in circumference toward the top where they terminate in simple caps similar to those of the Alexander Craig columns.

Among examples outside of Williamsburg of porches with turned columns having square bases are the following:

- Front porch of Viewmont, Albemarle County

- Front porch of Follen's House, near Cumberlanding on the Chickahominy.

The writers of this report have located no exact counterpart of the porch railing panels made up of random-width beaded boarding, but "filled in" railings were not uncommon in 18th century Virginia houses. An example, in which the "filling" consists of true panelling rather than boards fitted together is found in the "balustrade" of the gallery stairway of Abingdon Church near Gloucester Court House, Gloucester County.

OLD STAIR RAILING OF LEE HOUSE (NOW DEMOLISHED), AS SEEN FROM THE SECOND FLOOR LANDING.

OLD STAIR RAILING OF LEE HOUSE (NOW DEMOLISHED), AS SEEN FROM THE SECOND FLOOR LANDING.

There are plenty of precedent examples for the open type handrailing made of two beaded boards, separated from each other and from the handrail by open space, which descends the steps of either porch. An excellent local example is the one shown at the left—the old stair railing of the Lee House which formerly stood just east of the Scrivener House on Duke of Gloucester Street. The handrail of the Lee House stair, is, of course, different in profile from that of the Craig porch handrails.

45The plastering of porch ceilings was a frequent practice in colonial building. An old porch with such a plastered ceiling is the above-mentioned west front porch of the Coke-Garrett House.

BASEMENT STEPS AND BULKHEAD

Old basement steps, built apparently at the time the northwest portion of the building was erected, were found still in existence adjoining the foundations of the rear hall porch on the east. (See archaeological drawing, p. 7; photo, p. 10 and text p. 11). The right-angular cut-out in each brick step indicated that these had at one time had the wood nosings so frequently given to brick steps in the 18th century to save the brickwork from wear.

On the basis of this complete archaeological evidence the basement steps were rebuilt on the site of the old brick steps, which were thought to be in too poor a condition to retain. For practical reasons the six steps were made of reinforced concrete, with a steal angle (1½" x 1½" x ¼") placed at the junction of each tread and riser to prevent the wearing down of the concrete.

The elements of the bulkhead which are visible from the outside—the side walls of brick and the bulkhead superstructure of wood,—were designed in accordance with 18th century tradition in the treatment of such features. The bulkhead is of the sloping type and is similar in character to the old inclined bulkheads of the Taliaferro-Cole Shop and of Captain Orr's Dwelling. It is equipped with two swing doors made up of random-width beaded boards, each of which is held together by three battens nailed on the back at right angles to the boarding. The triangular sides of the wood framework are faced with random-width, beaded boarding running horizontally and the junction of the sides with the framework 46 of the top is covered by a pair of tapering rakeboards which diminish slightly in width from bottom to top. The lower edge of each board has been give a ½" bead and the lower end cut to a cyma recta curve.

WINDOWS

The dormer windows have already been covered under the subject of Dormers, pp. 36-38. In the course of this discussion, the relation of the dormer windows to the doors and windows below them was also treated in some detail, but the organization of the openings in the façades merits further consideration.