George Pitt House (LT) Architectural Report, Block 18 Building 4B Lot 47Originally entitled: "Architectural Report Pitt-Dixon House Block 18, Colonial Lot #47"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1394

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

[hand-written notes included with report]

Pitt-Dixon House

SM Comment

ALK Copy

March 9/1950

Title Page - [Wash.] Read also worked on this and I believe his initials are on some of the drawings.

p. 2 - line 15 - here are 2 photographs

p. 3 - 6th line from bottom - with a "cellar underneath" should read "...kitchen and cellar underneath"?

p. 4 - footnote - "the 20 x 40 House required by Act of 1705 (yellow lines)" I think if for 2 half acre lots, O.K.; for 1 half acre lot 20' x 30' was enacted. You may wish to check this.

p. 5 - 1st ¶ - check on 20 x 40 house as noted under p. 4.

2nd ¶ The 2 Coleman photos show a much longer house with 3 chimneys. Should we explain more fully how we arrived at the house with 2 windows, door, 2 windows & 3 dormers only above.

p. 7 - ¶ 3 - see under p. 4 above

p. 15 - 1st ¶ - line 4 - "...obviously new work..." would "...later work " be better?

There is a vertical joint between the front and later portion intentionally expressed in the reconstructed foundation wall. This deserves some mention.

5th ¶ - Best evidence for frame buildings in thickness of original foundations

p. 16 - 1st ¶ - can it be determined if there are colonial grades or modern compromise grades. Perhaps a note on this would clarify for future readers.

Chimneys - 1st ¶ - add "where exposed to eye".

- reference to 2 Coleman photographs?

p. 20 - ¶ 1 - This needs clarification - see specifications. Little if any white pine or cypress was used locally in 18th C. for trim or framing. No poplar was used in the reconstruction. in The materials specified no attempt to simulate colonial materials was made the guiding thought being to provide best modern material available for each purpose.

Some mention might be made of the fact that we did not employ face [nailing] on siding as all colonial houses were not face nailed.

Front Cornice - The use of modillions is shown in Coleman photos.

p. 21 - Corner Boards - A good original example of this expression of additions is front of Travis House.

Dormers - Precedent seen in Coleman photos.

p. 23 - Windows - Although the frames are designed to appear to be morticed, tenoned and pegged in reality they are not - as in nearly all reconstructed work & restored work which is concealed. This applies to doors also.

Muntins - Powder Magazine muntins are new - I believe no originals were left. Presidents House muntins are very late 18th century, being replacements of originals lost in the Revolutionary fire - I have a number of muntins as J.W.tt - if these were compared with those at Pitt-Dixon perhaps a more precise precedent could be quoted - if you have not already checked this for size.

p. 24 - window frames - I believe these were built up to appear like solid ones where exposed to the eye. See notes above.

p. 25 - 1st ¶ - Barraud House grilles are not quite the same - they have considerable iron work and the moldings vary. You may wish to check this.

p. 27 - See remarks above on 20x30 vs. 20x40 house of 1705 act.

p. 29 - Last ¶ - Mayo house was removed from its original site on north side of York St. by Decatur Mayo. I have a photo of it on original site at home. part of Coleman collection. You might wish to include this fact & even the picture. The Mayo house was not unlike Pitt-Dixon in form.

p. 39 - Hardware - Include hardware of exterior blinds & holdbacks. Also (p.38) Bulkhead has a reproduced colonial pad lock and chain.

p. 41 - Paint Schedule - old floors were cleaned and waxed only. New floors were stained and waxed. (see specifications)

General - A general statement should appear referring to special reports & glossary index for precedent for items where precedent is not mentioned.

For interiors some mention should be made to cover cornices in Hall to both front rooms, chair board in hall & Dining Room.

Door schedule: I was under the impression the woodwork was replaced at Blandfield in later times. You may wish to check this.

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

PITT-DIXON HOUSEBlock 18, Colonial Lot #47

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

PITT-DIXON HOUSE

(Reconstructed)

Block 18, Colonial Lot 47

The Pitt-Dixon House was reconstructed under the joint direction of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, Architects, and of the Department of Architecture of Colonial Williamsburg, Inc.

Archaeological Drawings dated August 18, 1932.

Reconstruction was started May 5, 1936.

Reconstruction was completed October 26, 1936.

A. E. Kendrew, Director of the Architectural Department

S. P. Moorehead, Assistant Director and Designer.

Working Drawings are by George S. Campbell and Richard A. Walker; Washington Reed.

This report was prepared by A. Lawrence Kocher and Howard Dearstyne for the Department of Architecture (Architectural Records) November 21, 1949-- corrections by S.P.M., March 9, 1950. Corrected by A.L.K. July 28, 1954.

THE PITT-DIXON HOUSE

Block 18, Colonial Lot 47

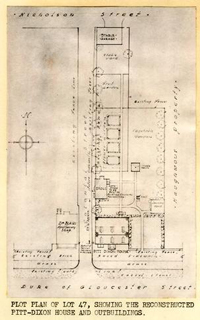

The Pitt-Dixon House is situated at the east end of Duke of Gloucester Street. It is an the north side of this street, east of a narrow lane designated, on old maps, as Colonial Street. The lot itself, on which the house and its varied dependencies are placed, extends through the block to Nicholson Street. It is shown on the Unknown Draftsman's Map of 1800 with the name of Hunter an its presumptive owner.

The house receives its name from two of its best-known occupants., Dr. George Pitt, a physician and apothecary, and John Dixon, -2- one of the editors of the Virginia Gazette. It served during its existence both as a shop and a dwelling and these two uses may at times have been combined. It was finally destroyed by fire late in the 19th century. The house in its latter days was recalled by Mr. John S. Charles as "a rambling dwelling" with three doors opening on Duke of Gloucester Street. Fortunately two photographs of the house were discovered in the Coleman Collection which proved an invaluable record and a guide to its reconstruction.

PLOT PLAN OF LOT 47, SHOWING THE RECONSTRUCTED PITT-DIXON HOUSE AND OUTBUILDINGS.

PLOT PLAN OF LOT 47, SHOWING THE RECONSTRUCTED PITT-DIXON HOUSE AND OUTBUILDINGS.

The original house has an unusual prominence as one of the first built in the City of Williamsburg during the first quarter of the 18th century. In its reconstructed story-and-a-half form it resembles somewhat the equally early Captain Orr's Dwelling and also the original Brush-Everard House, and as such it may be considered one of the characteristic, "native" houses of early Williamsburg. It was distinctly a middle-class house, the home of shop-keepers, and differed in both size and detailing from the larger and perhaps "grander" -3- examples such as the Carter-Saunders, the George Wythe and the Ludwell-Paradise House.

BASIS FOR THE DESIGN OF THE RECONSTRUCTED HOUSE

A house, believed to have been the original Pitt-Dixon, was advertised in the Virginia Gazette of November 7, 1754 as,

A very good dwelling-House, situate next Door to the Printing-Office, with a good Kitchen and Cellar underneath, Stable and Chair-House, Smoak-House, a good Well, and a Store adjoining, with a good Cellar underneath.

This graphic description of the dwelling and its site became the basis, in part, for the reconstruction of the Pitt-Dixon buildings by Colonial Williamsburg in 1936. Among the features of the house and lot to be noted from this description are: the outbuildings, separately listed, and the kitchen, which we are informed, was incorporated within the cellar of the house. It was fairly unusual to find a house in Williamsburg with a kitchen and "cellar underneath."*

When the house site was excavated in 1932 under the direction of the Department of Architecture, it was not without some excitement that the investigators came upon the brick-paved kitchen area and a large kitchen fireplace. The discovery of these features confirmed fully the Gazette description of 1754.

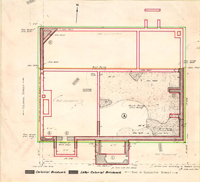

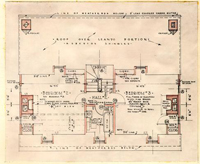

-4- COMPOSITE PLAN OF PITT-DIXON HOUSE SHOWING, SUPERIMPOSED UPON THE EXCAVATED FOUNDATIONS, 1-THE HOUSE AS RECONSTRUCTED (RED LINES); 2-THE 20 FT. X 40 FT. HOUSE REQUIRED BY THE ACT OF 1705 (YELLOW LINES); AND 3-THE HOUSE AS SHOWN ON THE FRENCHMAN'S MAP.

COMPOSITE PLAN OF PITT-DIXON HOUSE SHOWING, SUPERIMPOSED UPON THE EXCAVATED FOUNDATIONS, 1-THE HOUSE AS RECONSTRUCTED (RED LINES); 2-THE 20 FT. X 40 FT. HOUSE REQUIRED BY THE ACT OF 1705 (YELLOW LINES); AND 3-THE HOUSE AS SHOWN ON THE FRENCHMAN'S MAP.

THE WORDING OF THE ACT OF 1705 STIPULATES: THE REQUIREMENT THAT A HOUSE 40' X 20' BE ERECTED ON A ½ ACRE LOT AND A 50' X 20' HOUSE ON A PAIR OF HALF ACRE LOTS.

The original house thus revealed measures 40' in length by 20'-3" in depth. These dimensions and the "bricked" cellar floor have a special significance which links the house to the very early years of the 18th century. At that time the City of Williamsburg was first being populated by settlers who received a grant of 1/2 acre of land with the stipulation that they build a "Sufficient house" of brick or wood upon it within twenty-four months thereafter.1 That house, as further stated by the Act*, was "to have two Stacks of Brick Chimneys, a cellar under ye whole House," and was to be "forty Foot long & twenty Foot Broad..." The house is set back 6'-3" from the north line of Duke of Gloucester Street, again in conformity with the Act of 1705.

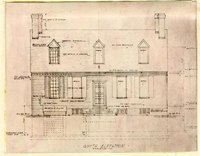

The old photographs from the Coleman Collection, mentioned above, which depicts the house as it stood in the latter half of the 19th century,2 was a third basis for the design of the reconstructed house. The picture shows the house as a typical steep-roofed Williamsburg dwelling, a story-and-a-half in height, sheathed with edge-beaded weatherboarding. It appears to have had on the Duke of Gloucester front, a center doorway with two windows placed symmetrically on either side. Three steep-roofed dormers project from the sloping roof of the building.

Mr. John S. Charles in his "Recollections of Williamsburg" relates his memory of the house as it appeared before its destruction by fire in 1896. He recalls it as "a long rambling two story frame building with three doors opening out upon Duke of Gloucester Street. The upper story of this house bad a very low pitch and the door at the western

-6- PHOTOGRAPH FROM THE COLEMAN COLLECTION, TAKEN ABOUT 1888 OR 1889, SHOWING (CENTER) THE PITT-DIXON HOUSE AS IT APPEARED TOWARD THE CLOSE OF THE LAST CENTURY, WITH DR. BLAIRS STOREHOUSE (THE PEDIMENTED BRICK STRUCTURE) AT THE LEFT; AND, PARTLY HIDDEN BY THE TRESS AT THE RIGHT, THE BUILDING WHICH AT THAT TIME OCCUPIED THE SITE OF THE VIRGINIA GAZETTE PRINTING OFFICE.

end... had a small platform with a railing around it, with steps down to the street." The Charles account, while not agreeing fully with the photograph, does bear out the general description given in the Virginia Gazette. The addition of two doors and a railed platform stems obviously from the late nineteenth century.

PHOTOGRAPH FROM THE COLEMAN COLLECTION, TAKEN ABOUT 1888 OR 1889, SHOWING (CENTER) THE PITT-DIXON HOUSE AS IT APPEARED TOWARD THE CLOSE OF THE LAST CENTURY, WITH DR. BLAIRS STOREHOUSE (THE PEDIMENTED BRICK STRUCTURE) AT THE LEFT; AND, PARTLY HIDDEN BY THE TRESS AT THE RIGHT, THE BUILDING WHICH AT THAT TIME OCCUPIED THE SITE OF THE VIRGINIA GAZETTE PRINTING OFFICE.

end... had a small platform with a railing around it, with steps down to the street." The Charles account, while not agreeing fully with the photograph, does bear out the general description given in the Virginia Gazette. The addition of two doors and a railed platform stems obviously from the late nineteenth century.

A PORTION OF THE FRENCHMAN'S MAP SHOWING PITT-DIXON HOUSE AND OUTBUILDINGS.

A PORTION OF THE FRENCHMAN'S MAP SHOWING PITT-DIXON HOUSE AND OUTBUILDINGS.

A further source of evidence as to the form and position of the original Pitt-Dixon House should be mentioned. The Frenchman's Map (ca. 1782) shows at the southwest corner of what has been identified as colonial lot 47 a building conforming both in shape and location to the Pitt-Dixon House as revealed by the old foundations. The approximately square shape of the structure indicated that the leanto had been added to the original house at the time that the French engineer viewed it.

DATING OF THE PITT-DIXON HOUSE

We can with reasonable certainty fix the date of construction of a house on colonial lot #47 as between September 3, 1717 and March 9, 1719.

William Timson, the first owner of lot #47, acquired it and two others (#46 and #323) from the Trustees of the City of Williamsburg under the terms of the Act of the Assembly of 1705. This act required the grantee to build within two years on each of. his lots on Duke of Gloucester Street (#46 and #47) a house of brick or frame construction, 40 ft. long and 20 ft. broad, lest the lots revert to the city.1

A little over two years after receiving the grant, William Timson sold his three lots to James Shield for £300. The amount paid by Shield indicates the possibility that considerable building bad been done on one or more of the lots between the time of their original acquisition and the -8- date of their sale.* One would assume that lot #47 was one of the lots built upon since Timson had retained it for several months more than the two year period within which he was required to build his house or return the lot to the city. It appears, nevertheless, that neither Timson nor Shield built upon the lot for the city was again in possession of it in 1717. On Sept. 3 of that year it made a second grant of lot #47, this time to Samuel Hyde.

Samuel Hyde held the lot for about a year and seven months and then (March 9, 1719) deeded it to Joseph Freeman. The original house was probably built by that time since the deed included, with the lot, "all houses, outhouses." The consideration, £ 10, seems small, but this may have represented a part payment only. That buildings of considerable value were on the lot when Hyde relinquished it is indicated by the fact that Freeman about three months later (June 15, 1719) transferred the property to Thomas Jones for the sum of £ 131. Freeman could scarcely have erected the house and outbuildings during his short tenure of the property.

To sum up: It appears a probability that a house, possibly the Pitt-Dixon, was built by James Hyde, some time between Sept. 3, 1717, when he acquired lot #47 from the city, and March 9, 1719, when he deeded it to Joseph Freeman. Though no explanation has been forthcoming as to how Timson could retain the lot for more than two years without building upon it, it nonetheless seems that he failed to build the required 20 ft. x 40 ft. house, since the lot reverted to the city. If the Pitt-Dixon House -9- was built, as the above facts seem to indicate, between 1717 and 1719, it was, as was stated above, one of the earliest dwellings to be erected in Williamsburg.

NOTABLE PERSONS ASSOCIATED WITH THE PITT-DIXON HOUSE

A number of persons of importance or interest were associated with the Pitt-Dixon House during its eighteenth century history. The first name, chronologically, with which there are significant historical associations is that of De Graffenried. Christopher De Graffenried, it seems, bought the property in 1722 and sold it in 1728. Nothing further is known of his tenure of the house and it is unlikely that he lived in it. He was a resident of Prince George County and is known to have maintained a town house near the Palace at the junction of North England and Scotland Streets, which he occupied on visits to Williamsburg.

It is not this Christopher De Graffenried, however, about whom the chief Colonial interest centers but rather his father of the same name. The elder De Graffenried, Baron Christopher, was a man of no little importance in the history of the settlement of the colonies. An "adventurer" or colonizer, born in Bern, Switzerland in 1661, he first sought to establish a settlement on the Potomac and at one time visited Williamsburg to seek military aid of Governor Spotswood. The Virginia undertaking ended in failure, but a second attempt at colonization - this time in North Carolina - succeeded. De Graffenried named the town which he founded New Bern after his birthplace. New Bern flourished and became the seat of government of the Carolina colony, with an Importance comparable to that of Williamsburg.

The next name of more than local note connected with the house is that of Dr. George Pitt, who acquired the property sometime between 1754 -10- and 1757, and owned it, except for a very brief interval, until 1774. Pitt was an apothecary-surgeon and a man of importance, apparently, since he is listed by one writer "among the physicians and surgeons who walked in the first circles about the time of the Revolution." Pitt's name appears in several notices of the time in the Virginia Gazette. From one of these (Feb. 12, 1762) it is evident that he carried on a drug business in the house, or, possibly, in the storehouse directly behind it.

Just Imported, a fresh Assortment of Drugs and Medicines, By the Subscriber, at the Sign of the Rhinoceros, next Door to the Printing Office, Williamsburg ....This is the only reference to the Pitt-Dixon House as "The Sign of the Rhinoceros" yet found, and one of the very few instances, altogether, in Williamsburg in which a house is designated by the name of the device or symbol on a sign hanging before it.

Though there seems to be no doubt as to Dr, Pitt's having been a personage of sufficient stature to justify the use of his name in the dual title of the house, we actually possess little information concerning him as an individual. One need not, however, be exceptionally adept at reading between lines to realize that he had an unusual wife. Sarah Pitt -- "much-marrying Sarah" -- entered wedlock with the Doctor possessing an impressive-matrimonial record,, having been wife of and widowed by both Capt. Graves Packe and Richard Packe, purchaser of the Pitt-Dixon House in 1739, and spouse as well of one William Green. At the period of her marriage to Pitt, in fact, there seems to have been some question as to whose wife she actually was, as the following Gazette item of 1755 suggests:

This is to give Notice, to all Persons that are indebted to the late widow Sarah Packe , now Sarah Green , not to settle with George Pitt, or any Person besides her Husband the Subscriber ... William Green .-11-

The reference to sums owed to Sarah Packe-Green recalls her career as tradeswoman, and here she was as versatile and ambitious as in the realm of matrimony.

As Sarah Packe, wife of Richard, she not only took in overnight guests at the Pitt-Dixon House but also operated at the same address a millinery shop where she sold "Bombazeens, Crapes, and other Sorts of mourning, for Ladies; also Hatbands, and Gloves, for Gentlemen." (Virginia Gazette, March 1, 1738). Later, she was partner to William Parks in the printing and bookselling business which the latter operated at his establishment on the lot adjoining the Pitt-Dixon property to the east. She was at this time still engaged in the millinery business, which she apparently continued to the day of her death, Nov. 12, 1772, on the occasion of which the Virginia Gazette carried the following announcement:

Last Monday died Mrs. SARAH PITT, Spouse to Doctor George Pitt, of this City; who bore a tedious Illness with much Christian Patience and Resignation, and was a Lady of a very amiable Character.

About two years after the death of his wife, Dr. Pitt deeded lot #47 to John Dixon, partner in the printing firm of Dixon and Hunter, located next door. Dixon held the property for a little more than six months and sold it to his partner, Hunter (William Hunter, II). Nothing further is known of Dixon's tenure of the house.

Since the fortunes of the printing establishment and the Pitt-Dixon House are merged at this period by Dixon and Hunter's ownership of both properties, a brief review of the history of the Gazette office after the death in 1750 of William Parks, the founder of the Virginia Gazette, should be of interest. A few months after Park's death the paper was revived by William Hunter, a great friend of Benjamin Franklin, who, in 1753, together with Franklin, was appointed a colonial deputy postmaster -12- general. Like Parks, Hunter printed books as well as the newspaper and also operated a bookstore on the printing house site. This first William Hunter died in 1761.

The paper then passed through a number of changes of editorship in quick succession, being managed first by Joseph Royle and then by Alexander Purdie, followed by Purdie in partnership with John Dixon. This combination continued until 1774 when John Dixon formed a new partnership, associating himself this time with William Hunter, son of the successor to William Parks. In 1779 Thomas Nicholson replaced Hunter in the partnership. Finally, in April, 1780, Dixon and Nicholson removed their office to Richmond, where John Dixon died in 1791, a respected citizen.

Dixon's earlier partner, William Hunter, II, who, as we have seen, bought the Pitt-Dixon House from him in 1775, ended his days, on the other hand, in poverty and disrepute. Hunter's sympathies during the Revolution were with the English and he made the fatal mistake of openly allying himself with them. His services to the Mother Country were sufficiently important to move Lord Cornwallis in 1784 to make to the British government the following declaration in his interest:

I certify that Mr. William Hunter joined the army under my command at Williamsburgh in Virginia, and rendered essential service by procuring intelligence of the Enemy, & by every other means in his power; and that He afterwards bore arms at the siege of Yorktown in a Company of Volunteers. He has sacrificed his fortune to his Loyalty, and He is now, I believe, in the greatest want of temporary subsistance.

The fortune which Hunter lost an a result of his adherence to the English cause, amounted, according to his own estimate,* to £ 5135, -13- a very large sum in those days. He lost, together with the Pitt-Dixon House, the printing office and a farm near Williamsburg, all of his slaves, livestock, household goods, a 40-ton sloop and other possessions. What recompense, if any, the English government made to him for his losses, is not known.

With William Hunter ends the roster of names of notable individuals associated with the Pitt-Dixon House. The house itself, or a house, at least, on the original site, survived until 1896 when it was destroyed by a fire which consumed all of the buildings in the block bounded by Duke of Gloucester, Botetourt, Nicholson and Colonial Streets.

PITT-DIXON HOUSE

Block 18 - Lot 47

EXTERIOR

BRICKWORK

- I.General

- What is included:

Foundations, chimneys, fireplace hearths, brick steps in bulkhead porch footings

- Indicate brickwork that is old, partly old, reproduction of old,

All brickwork exposed to exterior view is a reproduction of old brickwork, burned locally by 18th century methods and by use of local clay and sand.

- Color and textures

The brick color of Pitt-Dixon foundation is varied, not a uniform shade. The following colors prevail: dark red, gray-red, orange and purplish gray.

- Brick sizes:

The brick dimensions, are as follows: height, from 2 5/8" to 2 ½" (6 courses measured 18 ¼" from center of joint above to center of joint below); length, 9" to 9 ¼" and width, 4" to 4 ½". The mortar Joint varies from 3/8" to ½".

- Glazed headers, pattern, condition:

No use was made of brick patterning for foundations, other than that which results from the general run of brick coloring. Brick found in foundations, while considerable in quantity, was of a soft texture with disintegrated mortar. No use was made of standing foundations or floor paving, although this was originally contemplated.* Two vertical rows or glazed headers occur as shown on outer faces of chimneys.

- -15-

- Brick Bond:

English bond was found to have been used on foundation walls of the original building. English bond was therefore adopted for the renewed foundation. For the rear addition, which was obviously new work, Flemish Bond was used. The chimneys are laid generally in running bond, namely, with stretchers placed end to end. The brickwork of the chimneys at the two gable ends is laid with an approximation of Flemish bond, and including two vertical rows of glazed headers near the center of the exposed chimney face. Brickwork of fireplace interiors on the first and second floors is laid in English bond.

- Use of "rubbed" or "gauged" bricks:

No use was made of "rubbed" or "gauged" bricks, either for foundations or chimneys.

- Mortar:

This is the customary mortar, with oyster shell lime and local sand and cement added which is used by Colonial Williamsburg to give the appearance of old and original mortar. See Architectural Records Files for a full account of mortar and stucco. Mortar color for reproduced brickwork is a grayish tan. The joints are approximately 3/8" in width and are tooled.

- What is included:

- II.Foundations

In the reconstruction of houses of the restored area of Colonial Williamsburg, it is highly desirable that basements be kept as dry as possible. This is most effectively done by the use of a dense concrete for all foundations below grade line. The brickwork begins approximately three brick courses below finished grade, and continues for all exposed masonry.

- Archaeological Evidence:

The question arises, why was the house reconstructed with weatherboarding and frame? The house as recollected by Mr. Charles was of wood and the late 19th century photograph also shows a weatherboarded facing, above a fairly low brick foundation.3

- Give wall thickness of foundations:

Foundation walls of the archaeological drawings (1932) are given as 15" in thickness below grade. Reconstructed brick walls at the first floor line measure 13" in thickness.

- -16-

- Indicate grade levels:

Level of original brick paved cellar 76.25 " of reconstructed cellar floor 76.30 " of Heater Room floor 75.30 " of lst floor 81.00 Finish sidewalk grade (average) 4 81.00 Windows to basement are described under the subject, "windows."

- Archaeological Evidence:

- III.Chimneys

- Describe and indicate brickwork as original, partly rebuilt or reconstructed.5

All brickwork of chimneys is reconstructed in manner and appearance of original brickwork.

- Do chimneys project?

All chimneys are built within the area of the house since examination of archaeological drawings indicated this to be their original position.

- Plan of chimney at top, whether rectangular or T-shaped.

The two main chimneys at the gable ends are T-shaped in horizontal section. This shape was adopted in their reconstruction because they appear to be that shape in the Coleman Collection photograph.

- Treatment of chimney cap:

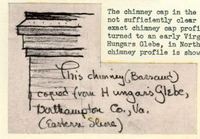

The chimney cap in the Coleman photograph was not sufficiently clear in detail to give the exact chimney cap profile. The designer then turned to an early Virginia example, namely Hungars Glebe, in Northampton County. This chimney profile is shown at the left.

- -17-

- For Fireplaces, see Index under "chimney pieces."

- Describe and indicate brickwork as original, partly rebuilt or reconstructed.5

- IV.BRICK FLOORS AND PAVING

While brick floors were found in the excavated basement, it was decided not to restore these, since the reconstruction was restricted to a reclaiming of the external appearance. There were no instances of paving of porches or floors above grade.

- V.BRICK STEPS AND LANDINGS, WHERE USED:

Steps to the basement, within the bulkhead (north side) are of brick with oak nosings. Details of treads and a stairway of this character may be seen at the Wythe House on the Palace Green. See Wythe House report for description.

- VI.GUTTERS OF BRICK

There are no gutters of brick since metal gutters were adopted and installed, excepting on the south front of the house, where no gutter occurs at roof edge or base of the building.* From archaeological evidence (discovery of several brick gutters at base of walls) wall base gutters were fairly common in Williamsburg. These had the advantage of freeing the roof edge from a disfiguring metal gutter, and also of effectively protecting the exterior of foundation from roof drainage. It is probable that some of the gutters found in the town were late additions, installed at a date later than that of the erection of the house to keep the basement dry.

STONE MASONRY

- Is use made of imported English or American stone?

The front main entrance steps are of Indiana limestone, selected for its resemblance to the English Portland or Purbeck stone. The latter stones were used fairly extensively for the paving of porches, halls and terraces. Indiana limestone from the Bedford quarries is near in appearance to the Portland. The American stone was favored on some of the restoration jobs because of the -18-

All of the above nosings are original, with the exception of the Pitt-Dixon example, which is reconstructed. All are found on square or rectangular porches.

-19-

delays in obtaining the English stone. The Indiana limestone was given the same tooled finish that was applied to the imported stone.* The front steps are square in shape, fitted precisely to the square foundation of the archaeological plans. Each step edge has a rounded nosing - a detail that repeats the nosing of original steps of The President's House at the College. (See page entitled, "Comparative Stone Nosings from Virginia Houses"). The square steps and landing with their rounded nosings are a replica of the square steps at the south entrance of the John Blair House. The stone stoops of the two buildings are more or less equal in size. Both are approximately 10 ft. long; the Pitt-Dixon stoop is somewhat deeper, being 7'-1-½" in depth as against 6'-0 ½" for the Blair. The stones composing the platforms and steps of both stoops are held in place by wrought iron cramps set in lead. The Blair steps were not originally placed at the entrance to the Blair House, but are attributed by unsupported tradition to the old Theatre, that was said to have stood on the Palace Green, and that served for a period as a court house.

All of the above nosings are original, with the exception of the Pitt-Dixon example, which is reconstructed. All are found on square or rectangular porches.

-19-

delays in obtaining the English stone. The Indiana limestone was given the same tooled finish that was applied to the imported stone.* The front steps are square in shape, fitted precisely to the square foundation of the archaeological plans. Each step edge has a rounded nosing - a detail that repeats the nosing of original steps of The President's House at the College. (See page entitled, "Comparative Stone Nosings from Virginia Houses"). The square steps and landing with their rounded nosings are a replica of the square steps at the south entrance of the John Blair House. The stone stoops of the two buildings are more or less equal in size. Both are approximately 10 ft. long; the Pitt-Dixon stoop is somewhat deeper, being 7'-1-½" in depth as against 6'-0 ½" for the Blair. The stones composing the platforms and steps of both stoops are held in place by wrought iron cramps set in lead. The Blair steps were not originally placed at the entrance to the Blair House, but are attributed by unsupported tradition to the old Theatre, that was said to have stood on the Palace Green, and that served for a period as a court house.

ROOF

Form of the roof.

The roof of the front part, considered the original house, was A-shaped, with a one-story leanto addition at the rear.

The slope of the A roof is 50 degrees, which is steeper than average. This slope is associated with the earliest houses of Williamsburg,, such as the Timson and Captain Orr's dwelling. The slope of the roof of the leanto addition is 19 degrees.

EXTERIOR WALLS

Framing Methods, plates joists, etc.

All framing is new and no attempt has been made to follow old methods of joining members together.

-20-Special Kinds of Woods for framing and finish

Although the framing methods are new the materials used are similar to those employed in the 18th Century. Use was made of yellow pines cypress (for sills) and white pine for finish as was the case in colonial times. Some poplar was also used.6

Types of facing

Weatherboarding - The exterior of the house was faced with beaded weatherboards with an average exposure of 6". The bead is the typical ½" round bead.

Flushboarding - The gable ends of the dormers have random-width, flush, unbeaded boarding, running horizontally, while the sides are faced with diagonally placed, random-width, flush, beaded boarding.

EXTERIOR TRIM

Main (Front) Cornice

This is a modillion cornice consisting of a crown mold, fascia, modillions and bed mold. It is similar to the front and rear cornices of the Lightfoot House and-to the cornice of Wales, Dinwiddie County. 7

Rear Cornice

This is the typical cornice used with the leanto roof and consists of a crown and bed molding only. Cornices of this type were used locally on the leanto of the Moody House and of the Pallard House, an old house moved by James Cogar in 1948 from King and Queen County to a site on York Street. In most wood houses of Williamsburg the front and rear cornices differs, whether or not they have leanto additions.

Cornice End Boards

No precise precedent has been established for this cornice end board (see working drawing #203). Details of cornice end boards, and of step ends, baluster profiles etc. were varied in the 18th century with practically no instances of duplication, so that it is difficult, if not impossible, in many cases, to find the precise precedent for a given example. The cornice end board of the Pitt-Dixon House has been designed to follow the spirit of colonial end boards of Williamsburg and the Tidewater area. The main curve of the board is similar in a general way to that of the end board at the southwest corner of the Travis House. The wood half-circle at the bottom recalls a similar feature of a house in Smithfield, Isle of Wight County.

-21-Corner Boards

These are single-faced and have their broad sides toward the front and the rear. Examples of single-faced corner boards are found on such old Williamsburg buildings as the Orrell, Bracken and Timson Houses.

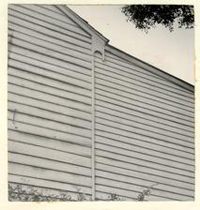

At either end of the house, at the junction of the main building and the leanto, a "vestigial" corner board, 1 ½" wide, was used to indicate the point in the original building where the main part ended and the leanto began. An old Williamsburg dwelling, the Spencer Lane house on Waller Street, retains this feature between the house proper and the leanto (see photo). The Market Square Tavern and the Travis House both have such erstwhile corner boards on their front facades, indicating that these buildings were at one time lengthened.8

Treatment of the Gables: Rakeboards and Moldings

All rake or bargeboards are 5 ¼" wide at their lower ends and taper slightly toward the peak of the gable. They are flush with the cornice end boards and merge with them. They overlap the weatherboarding of the gable ends projecting 3 ¼" beyond the surface of the weatherboarding. An ogee molding runs along the upper edge of the rakeboards to receive the projection of the shingles of the roof.

"VESTIGIAL" CORNER BOARD BETWEEN MAIN BUILDING AND LEANTO -- SPENCER LANE HOUSE, WILLIAMSBURG.

"VESTIGIAL" CORNER BOARD BETWEEN MAIN BUILDING AND LEANTO -- SPENCER LANE HOUSE, WILLIAMSBURG.

DORMERS

Type, number and location

The dormers, 6 in number (3 at the front and 3 at the rear) are gable-ended with sharply tapered rakeboards. They have been located on both front and rear so as to line up with either a window or door in the first story.

Slope of roof

The roof slope, 50 degrees, is identical with the slope of the main roof.

-22-Facing of gable end and sides

As noted elsewhere, the gable ends are faced with horizontal, random-width, unbeaded flush boarding while the sides have diagonally-placed, random-width, flush beaded boards.

Precedent

The Bracken House has similar gable-ended dormers with windows 5 lights high and 3 lights wide. For a discussion of the dormer sash, see "Windows."

Front Stoop

The front stoop, with its stone steps and platform is discussed elsewhere.

Rear Stoop

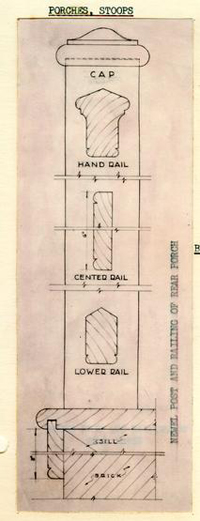

This porch, of wood, is 4'-6" in width and projects 3'-0" from the face of the building. It is approached from the front side by means of a flight of steps with 6 risers. It has a railing at either side which continues down the steps. This railing with its newel posts in of the designed type, patterned after old stoops of Tidewater Virginia (see sketch at left.)

BULKHEAD

The design of the leanto-type bulkhead, of which there are many restored examples in Williamsburg, is derived from old bulkheads at the Taliaferro Cole Shop and Captain Orr's Dwelling. It has a pair of doors made of random-width flush beaded boards and the sides are faced with random-width, flush, unbeaded boards. Instead of the usual tapered rakeboards it has, beneath the top at either side, a reverse curve molding. The bulkhead rests on a brick foundation, laid in English bond, which rises two courses above the ground.

For the bulkhead hardware, see "Hardware."

WINDOWS

Type or types - operation method

All windows throughout the house are double-hung. They are constructed with mortise and tenon joints, secured by wood pegs. 9

Number and arrangement of lights and glass size

- Ground floor, front and gable ends, main part

Eight windows, 3 lights wide, 6 lights high.

Glass size - 9"x12"

Precedent - First floor windows of the Bracken House, and of Montpelier, Charles City County. - Ground floor, rear and sides of leanto

Four windows, 3 lights wide, 5 lights high

Glass size - 9"x11"

Precedent - Windows of the Annie Galt House which have 6 lights in the upper sash as do these. - Gable ends, second floor

Four windows, 2 lights wide, 4 lights high

Glass size - 8"x10"

Precedent - Windows of west gable end of Coke-Garrett House. - Dormers

Six windows, 3 lights wide, 5 lights high

Glass size - 8"x10"

Precedent - Windows of Annie Galt House - Basement - east side, northeast corner

One window, 3 lights wide, 4 lights high

Glass size - 9"x9"

Precedent - First floor windows of the Quarter and second floor windows of Montpelier, Charles City County. - Muntin bars

These bars are the usual muntin bars associated with early houses of the 18th Century. Precedent: Muntin bars of windows of President's House, College of William and Mary, the Powder Magazine and the Barraud House.

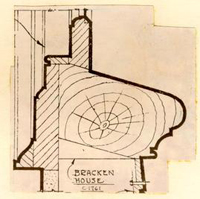

Window Sills

The sills on the ground floor of the main part of the house are of the rounded type, beaded at the bottom, with the bead lining up with the bead of the adjacent weatherboarding. The sills of the second floor of the "old" part and of the leanto are square. Precedent for the rounded sill are old sills of the Bracken House (see sketch) and also sills of the St. John's House, which once stood near the Williamsburg Inn.10

Precedent for the square sill are old sills of the Timson House and of Wales, Dinwiddie County.

SECTION THROUGH OLD SILL OF BRACKEN HOUSE

SECTION THROUGH OLD SILL OF BRACKEN HOUSE

Window trim

Exterior. The exterior trim throughout consists of a simple flat band 2 ½" on the face and 1 ¼" thick) which receives the shutters. Old examples of this type of trim have been found on the following houses: Casey's Gift, Williamsburg, Main Farm in the vicinity of Williamsburg, and the Joiner House, Nansemond County.

Interior. The interior window trim in all cases enframes the windows completely and interior sills are therefore absent. The trim is of either the single or the double-molded type.

Window frames

The frames are solid, with a chase to receive a single sash weight. Solid frames are a customary feature of early buildings and may be observed in any eighteenth century house in Williamsburg - a specific example in the Bracken House. Examples of old solid sash frames and sills are in the collection of original building parts now being assembled by the Department of Architecture, Goodwin Building.

Basement window grills

There are 6 of these located on the front and sides of the main Part of the house. They have solid frames, mortised and tenoned, and -25- secured with wood pins. The frames have a vertical division at the center and 3 horizontal bars, placed on the diagonal. These grilles are, in all details, replicas of the original basement grilles found at the Barred House. 11

SHUTTERS

The shutters are of the louvred type with a central horizontal division lining up with the meeting rail of the windows. Similar old louvred shutters are found on the Powell-Hallam, Lightfoot and Barraud Houses.

For shutter hardware, see "Hardware."

EXTERIOR DOORS

For treatment of exterior doors and door trim see Door Schedule.

SUMMARY

The reconstructed Pitt-Dixon House is a more or less typical Williamsburg house, of which Captain Orr's Dwelling is a good original example. In the design of all of the details of the exterior the architects followed authentic 18th century examples. In the framing, however, modern construction methods were used and the plumbing, electrical and heating equipment installed on the interior are, of course, entirely modern.

INTERIOR

The Pitt-Dixon House Interior was reconstructed for use as a dwelling. Externally it was rebuilt so as to appear as did the early 18th century original house. In its form it was fitted to the outlines of the foundations as excavated. Since the house was not intended for exhibition, it was not given the precise plan features of the old and original house.

The Pitt-Dixon house was first, in 1932, scheduled for use as an adjunct to the Williamsburg hotels. It was later, in 1936, replanned as a dwelling and as a part of the group of buildings revealed on lot 47 during the process of excavation in August, 1932. The floor plan was adjusted to convenience of present-day living, and additions of bathrooms, a kitchen, and heating and lighting were made. A full discussion of the subject of adjustment to present-day occupancy is to be found in the Architectural Report titled, Approved Methods of Restoration at Colonial Williamsburg .

PLAN TYPE

The floor arrangement of the original house may be characterized as a "center hall," one-room-deep plan. This plan was believed, by the architects, to have been added to at the rear, so that its depth was increased from 20' to 31'-6". The dimensions of the original plan, which measured 20 by 40 feet, were thought to have been determined by the Act

-27-

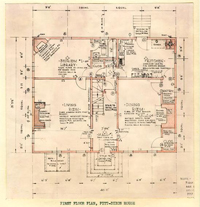

FIRST FLOOR PLAN, PITT-DIXON HOUSE

of 1705, "Directing ye building ye Capitol and ye City of Williamsburg," which called for the house size found by the excavations. 1 12

FIRST FLOOR PLAN, PITT-DIXON HOUSE

of 1705, "Directing ye building ye Capitol and ye City of Williamsburg," which called for the house size found by the excavations. 1 12

SECOND FLOOR PLAN, PITT-DIXON HOUSE

SECOND FLOOR PLAN, PITT-DIXON HOUSE

The addition to the rear follows foundation evidence, and also evidence furnished by the Frenchman's Map. The house on the Pitt-Dixon site shown on the map is apparently a two-room-deep building.

WHAT IS INCLUDED IN THIS REPORT

Discussion of the interior of the Pitt-Dixon House will be restricted to those parts which in their reconstruction, were built of old and original woodwork salvaged from other Williamsburg or Tidewater-Virginia houses.

-29-ANTIQUE MATERIALS WERE USED AS FOLLOWS:

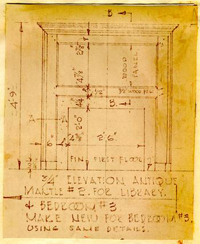

Living Room - Panelled wainscoting, except the required new cap and base moulding; antique mantel No, 25, and finished floor.

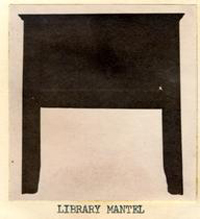

Library - Antique mantel No. 2, and finished floor.

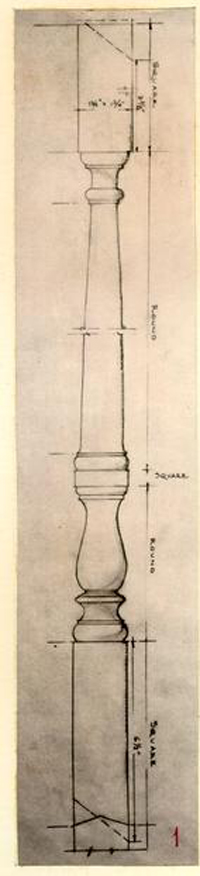

First and Second Floor Halls - Antique stairway from the Mayo House which stood formerly in Block 8, on Capitol Square. This stairway was adapted to the space and stairway requirements of the Pitt-Dixon house plan. Use was made of posts, rails, balusters and even risers and treads. The floors from 18th century buildings.

Baseboards and chair railings are partly old, selected from the supply of salvaged woodwork, stored at the time of the reconstruction of the house in the Warehouse of Colonial Williamsburg.

FLOORS

The floors of the principal rooms consist of old flooring, salvaged from early Virginia buildings. Old flooring was installed in the hall living room, library and dining room.

Floor boards referred to as "antique" are of yellow pine, laid, as they were originally, mostly with edge grain exposed as the walking surface. These boards vary in width from approximately 5" to 7". Their thickness is 1 1/8". Old flooring, relaid, requires cutting of the under surface of boards so as to obtain a level top surface. All flooring boards were applied to the joists by means of surface nailing, using wrought iron nails.

For Floor Finish , see painting schedule.

STAIRCASE

Type of stairs

The staircase of the Pitt-Dixon House has an open well, and is typed as a "mixed" stairs, because of the combination of a straight run and winders. The end stringers are closed. The interposition of a square platform after five descending steps was a safety device or landing, to reduce the danger of stumbling in making the descent.

Is it original-or a reproduction?

The stairs are old, having been removed from the 18th century Mayo house which stood in Block 8, Capitol Square. 13

-30-DIMENSIONS AND DETAILS OF STAIRWAY

The basic dimensions of the stairway as shown on the plans are as follows:

| Width, wall to center of railing: | 3'-0" |

| Riser height: | 7 ¼" or - |

| Tread width (incl. nosing): | 10 ½" |

| Number of risers of which 2 are winders: | 17 |

| Height of railing over riser: | 2'-6 ½" |

| Height of railing 2nd floor | 3'-3" |

| Newel Post, square: | 3 ¾" sq. |

| Balusters, 3 to a tread | 3" o.c. |

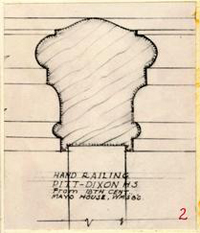

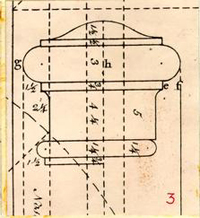

Illustration nos. 1, 2, and 4 are drawings of details from the old Mayo House stair, re-used in the Pitt-Dixon House (1 - baluster; 2 - handrail; 4 -,contour both of the platform edge and the stair nosing). No. 3 is the detail of a handrail from a builder's handbook. Details such an this were frequently used at the time as a basis for the design of stair railings, balusters and other building features.

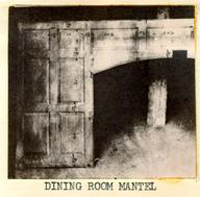

ORIGINAL MANTELS FROM OLD VIRGINIA HOUSES USED IN THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE PITT-DIXON HOUSE.

THE PHOTOGRAPHS AT LEFT SHOW THE THREE ORIGINAL MANTEL PIECES USED IN THE PITT-DIXON HOUSE.

Of the four mantels in the house three are original wood mantels obtained from 18th century Virginia houses, and the fourth, the mantel of the east bedroom, is an exact copy of one of these. The three "antique" mantels, illustrated at the left, were, at the time of the reconstruction of the Pitt-Dixon House, a part of the collection of old materials stored in the Colonial Williamsburg warehouse. Although, in using the mantels it was necessary to replace a few missing parts and to make some minor repairs, the chimneypieces remain today very much as they were when they stood in their original locations.

The smallest of the three mantels, a single paneled example of simple design, was used as a surround of the corner fireplace in the library. This is the mantel, referred to above, which served as a model for the reconstruction of the chimneypiece of the east bedroom. In installing the mantel a square plaster frame was added about the fireplace opening. The inner edges of the mantel sides, which were ragged, possibly from burning, had to be repaired and new plinth blocks were added at the base.

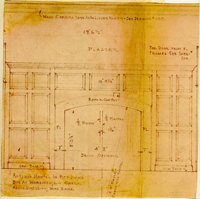

The mantel used in the dining room stood originally in the Wellons (?) House, in Southhampton County. It in a large chimneypiece, 10'-8 1/8" wide, with 15 panels and a segmental-arched opening. The mantel shelf was missing and a molded shelf or top rail with dentils was added. A new base was provided and a notch which had been cut out of the rounded arch was filled. The usual plaster margin or frame was placed about the fireplace opening.

It is of interest that the side walls of the plan of this fireplace are perpendicular to the back and that these walls are joined by a curve with the back walls. Such rounding of the inner corners of the fireplace (the rounded corners were called "covings") was a common practice of the first quarter of the 18th century. Covings are found, for example in fireplaces at Rosewell, Gloucester County. The curved corners were later eliminated and the sides made oblique or "sloped" in order better to reflect the heat into the room.

-32-"Antique" Mantel from an old (unrecorded) house, of Virginia, and one of the mantel collection assembled by Colonial Williamsburg Inc. for re-use in reconstructed houses of the town.

This mantel shown an previous page was cleaned, repaired and plinth blocks added. It was then installed in the library of the Pitt-Dixon House. The plastered frame surround to the fireplace opening was built in conformity with the local brickwork practice.

A replica of this old mantel was made and installed in the east bedroom of the second-floor.

-33-Drawing of "antique" wood mantel, selected from an assembly of old mantels stored at the Colonial Williamsburg warehouse. This mantel was repaired with the addition of a new mantel shelf and base, then installed in the dining room of the Pitt-Dixon House. It is an early mantel type, suited to a room with a panelled dado.

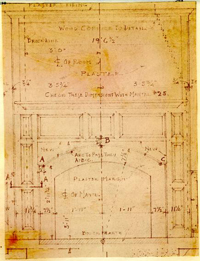

-34-Drawing of "antique" mantel installed in living room of Pitt-Dixon House. This old and original architectural fragment from an early (unrecorded) Virginia house was fitted against a chimney with a 7 ½" wide plastered-arch frame. No alteration to the fireplace facing was made, although a squared spandrel of wood was placed above the segmental arch. This is noted on the drawing as "new."

-35-The old mantel used in the living room is a 9-paneled example, smaller than that of the dining rooms, but so similar in general design character that it may be called a companion piece to it. In applying it to the fireplace wall an overmantel was added, with a plaster "field" enclosed in a wood frame, the sides and cornice of which are new. New wood spandrels were also provided which form a segmental arch between the mantel proper and the plastered frame of the fireplace opening. This fireplace, like that of the dining room, has the inner angles of the opening rounded.

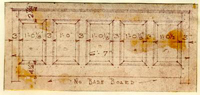

OLD PANELING OF LIVING ROOM

Another "antique" feature of this reconstructed house in the old paneling installed an a dado or chair rail-height wainscot around the walls of the living room. This paneling, originally from an unidentified 18th century Virginia house, had been stored in the Colonial Williamsburg Warehouse until its re-use in the Pitt-Dixon House.

The living room dado rises to a height of about 2'-8" above the floor and is composed of molded raised panels which, for the most part, are approximately 1'-0" x 1'-8 ½" in size.

It was necessary, in fitting the old woodwork around window and door openings to cut down some of the panels and a few new panels had to be added. A total of about 55 running feet of old paneling was used in the room. The original cap and baseboard no longer existed so that these elements also had to be replaced.

PITT-DIXON HOUSE -- BLOCK 18-2

| Door No. | Location | Width | Height | Thickness | Panels | Trim | Precedent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | West B.R. to Closet | 2'-3" | 6'-3" | 7/8" | Batten door | Flat trim, beaded - both sides. | Outbuilding of Marmion, King George Co. |

| 101 | Hall to west B.R. | 2'-6" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | 6 Panels, raised 1 side | Single-molded, both sides | Barraud House - old interior doors. |

| 102 | Hall to bath | 2'-4½" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | 2 panel, raised 1 side | ditto | ditto |

| 103 | Hall to east B.R. | 2'-6" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | 6 panel, raised 1 side | ditto | ditto |

| 104 | East B.R. to closet | 2'-3" | 6'-3" | 7/8" | Batten door | Flat trim, beaded - both sides | Outbuilding of Marmion, King George Co. |

| Door No. | Location | Width | Height | Thickness | Panels | Trim | Precedent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Ext.) | Front Door | 3'-0" | 7'-4½" | 1½" | 8 panels, raised both sides | Double-molded, both sides: Outside 6" high, inside 5½" | Front doors of Blandfield, Essex Co. & Wilton, Henrico |

| 2 | Hall to L.R. | 2'-10" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | 6 panels, raised 1 side | Double-molded, both sides | Barraud House - old interior doors. |

| 3 | L.R. to Libr. | 2'-8" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | ditto | Double-molded, L.R. side Single-molded, Libr. side | ditto |

| 4 | Rear Hall Cl. | 2'-6" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | ditto | Single-molded, both sides | ditto |

| 5 | Libr. to Bath | 2'-6" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | ditto | ditto | ditto |

| 6 | Rear Hall Cl. | 2'-6" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | ditto | Single-molded, hall side | ditto |

| 7 | Between Rear Hall Closets | 2'-6" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | ditto | ditto | ditto |

| 8 | To Basement | 2'-7 ½" | 6'-0" | 1 1/8" | ditto | ditto | ditto |

| 9 | Rear Front Hall | 2'-6 ¾" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | ditto | ditto | ditto |

| 10 | Rear Hall to Kitchen | 2'-6" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | ditto | Single-molded, both sides | ditto |

| 11 (Ext.) | Exterior Kitchen | 2'-10" | 6'-5" # | 1 ½" | 2 panels at base, glazed above, 9 lights 4 light transom. | Single-molded, both sides. Trim height, outside 5". | Old door of Lee House # |

| 12 | Kitch. to Pantry | 2'-8" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | 6 panels, raised d1 side | Barraud House - old interior doors | |

| 13 | Pantry to D.R. | 2'-8" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | ditto | ditto | |

| 14 | D.R. to Closet | 2'-8" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | ditto | ditto | |

| 15 | D.R. to Hall | 2'-10" | 6'-6" | 1 1/8" | ditto | Double-molded, both sides | ditto |

HARDWARE 14

Hardware for the Pitt-Dixon House was reproduced from old examples, wrought by hand in the shop of Colonial Williamsburg or was made by shops of the locality, The manner in which replicas of old hardware are made is fully discussed and illustrated in an Architectural Report titled: Basic Restoration Methods of Colonial Williamsburg, on file in the Records Files of the Department of Architecture.

The listing of Pitt-Dixon hardware follows:

- Bulkhead

(exterior)

2 Pr. T shape strap hinges 24" length

1 Hasp and Staple. - Door #1

(exterior, main entrance)

1 Pr. 12" H-L Hinges, wrought iron

1 Brass Rim Lock 4 1/2" x 8" - Door #2

(Hall to L.R.)

1 Pr. 12" H-L Hinges

1 Iron rim lock-Reading - Door #3

(L.R. to Library)

1 Pr. 12" H-L hinges

1 Iron rim lock-Reading - Door #4

(Library to rear Hall Clos.)

1 Pr. 10" H-L Hinges

1 Iron rim lock - Door #5

(Library to Bath)

W.I. thumb latch, modern

hinges and slide bolt - Door #6

(Rear hall closet)

1 Pr. 10" HL hinges

1 W.I. thumb latch - Door #7

(Rear hall door)

1 Pr. 10" HL hinges

1 W.I. thumb latch - Door #8

(Door to basement from hall)

1 Pr. 8" H L hinges

1 W. I. thumb latch - -39-

- Door #9 (Door between front and rear halls) 1 Pr. 10" HL Hinges 1 W.I. thumb latch

- Door #10

(Rear hall & kitchen)

Modern hinges and stock iron rim lock. - Door #11

(Exterior rear)

1 Pr. modern butt hinges

1 iron rim look - Reading

Transom has stock butt hinges and

1 modern transom sash adjuster. - Door #12

(Kitchen & Pantry)

Modern hinges

1 Stock iron rim lock - Door #13

(Pantry and D.R.)

1 Pr. 100 H-L hinges

1 Iron rim lock - Door #14

(D.R. & closet)

1 Pr. 10" H-L hinges

1 Iron rim lock - Reading - Door #15

(Din. R. & front hall)

1 Pr. 10" H-L hinges

1 Iron rim lock-Reading

2nd Floor

- Door #100

(West B.R. and clos.)

1 Pr. 8" H-L hinges

1 W.I. thumb latch - Door #101

(Hall to W. Bed Room)

1 Pr. 10" H L hinges

1 Iron rim lock - Reading - Door #102

(Hall to Bath)

1 W.I. thumb latch

Hinges and bolts are modern - Door #103

(Hall to E. Bed Rm.)

1 Pr. 10" HL hinges

1 Iron rim lock - Reading - Door #104

(Batten to S. E. Closet)

1 Pr. 8" H-L hinges - Bed Room Cupboards

(north side)

4 Pr, 4" H-L hinges

PAINTING

| Location | Color No. | Description | Finish |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living Room, woodwork | 604 | Spanish brown | Satin |

| Hall, 1st.& 2nd floor, baseboards & handrail | 92 | Varnish over burnt umber | Varnish |

| Kitchen, woodwork | 610 | Light olive gray-green | Satin |

| Hall, 1st and 2nd floors, woodwork | 612 | Strong Grey blue | Satin |

| Dining room, dado wall | 617 | Pale umber grey | Satin |

| Library & 1st fl. Bath, woodwork | 608 | Grey Blue | Satin |

| Dining room, Pantry, dining room closet, woodwork | 606 | Reddish gray | Satin |

| East & West bedrooms & bath, 2nd floor, woodwork | 613 | Gray with very pale green tint | Satin |

| Library, Walls | 607 | Light French Grey | Perfect flat |

| Dining room, pantry, dining room closet, ceiling & walls | 41 | Off white, cream | Perfect flat |

| Living room, walls | 18 | Pale flesh white | Perfect flat |

| Hall, 1st & 2nd floors, walls | 611 | Cream white | Perfect flat |

| Kitchen, walls | 18 | Pale flesh white | Satin |

| -41- | |||

| Bath, 1st floor walls | 609 | Pale yellow ochre, nearly white | Satin |

| East & west bedrooms & bath, 2nd floor, walls | 717 | Pale grey | Perfect flat |

| Location | Color No. | Description | Finish |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exterior panels, muntins on exterior doors, woodwork | 605 | Medium yellow brown | Lead |

| Porch floors, exterior door | 25 | Warm raw sienna tan | Masury's Deck Paint |

| Exterior blinds, bulkhead doors, basement sash, woodwork | 603 | Olive green | Lead |

| Exterior trim, woodwork | 602 | Tan cream | Lead |

| Exterior body woodwork | 601 | Maple | Lead |

All old floors were given a coat of stain, followed by two coats of wax. New floors were stained in such a manner as to simulate the appearance of old material. 15

Footnotes

"... a House [at capitol Landing], 40 Feet long, and 20 feet wide ... a brick cellar from End to End, Part whereof is a Kitchen..." (April 29, 1737)

"...in the City of Williamsburg a dwelling house in Good repair with a Kitchen under it and two large brick vaults..." (June 1, 1771)

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS USED IN ARCHITECTURAL RECORDS

(To be attached to every record and to be used in the interpretation of reports.)

The word "existing " is used in these records to indicate whatever in the building was in existence previous to the restoration by Williamsburg Restoration or Colonial Williamsburg.

The phrase "not in existence " means "not in existence at the time of the restoration."

The word "modern " is used as a synonym of "recent" and is intended to indicate any replacement of what was there originally and of so late a date that it could not be properly retained in an authentic restoration of the building. It must be understood, however, that restored buildings do require the use of some modern materials in the way of framing as well as modern equipment.

The word "old " is used to indicate anything about a building that cannot be defined with certainty as being original but which in old enough in point of time to, justify its retention in a restored building for the period in which the house was built.

The word "ancient " when used in these reports is intended to mean "existed long ago " or "since long ago ." Because of the looseness of meaning, the term is seldom used and then only to denote great age.

"Antique " as applied to a building or materials, is intended to mean dating before the Revolution.

"Greek details", "Greek mouldings" are references to the mouldings, and architectural treatment featured by the Greek Revival, dating in this locality approximately from 1810 to 1860.

-43-Length signifies the greatest dimension of a building measured from end to end.

Width is used in the reports to mean the dimension of a building measured at right angles to the length.

Depth , as applied to the size of a lot or house is the dimension measured at right angles to the street.

Pitch is here interpreted as meaning the vertical height from floor to floor.

The term "restoration " is applied to the reconditioning of an existing house in which walls, roof and most of the architectural details are original, but with replacement of decayed parts, and some missing elements such as mantels, stairs, windows, cornices, dormers.

The expression, a building "preserved ", has reference to a building in its pristine condition, without replacement of elements, such as stairway, windows, paneling, mantels, flooring. The term preservation does imply however, necessary repairs, to protect it from weather, decay, excessive sagging.

"Reconstruction " is applied to a building rebuilt on old foundations, following the documentary description of the original structure. The reconstructed Capitol, as an example, is a rebuilt building, following Acts of the Virginia Assembly, 1662-1702, also with use made of pictorial data, the Bodleian Plate, recorded measurement and drawings.

It is to be noted that the existing roof covering, whether original or modern, has been replaced in all the restored buildings -- with a few minor exceptions, by shingles of fireproof material (asbestos cement) because of the desirability of achieving protection against fire.

DATING OF A BUILDING

The dating of a house or other building is based upon one or more of the following:

- 1.Actual date of the house visibly signed on its brickwork, framework, etc.

- 2.Literary references such as:

- a.A record stating when a building was started, was in course of erection or completed.

- b.A record which would imply that a house was being occupied at a given date.

- c.Correspondence referring to a house as under construction or as having been completed.

- d.Advertisements referring to a house as for sale or implying its existence.

- e.House transfers by will (wills frequently contain inventories of the contents of a house), sale or default in payment.

- f.Fire insurance policy declarations.

- 3.Documentary evidence such as that furnished by maps; buildings may be indicated on maps, the dates or approximate dates of which are known.

- 4.Historical references to the building such as found in the record of the meeting at the Raleigh Tavern in 1765 to defy the Stamp Act.

- 5.5. Existance of original plans or draughts of a building; drawings of exteriors of buildings such as Michel's drawing (1701, 1702) of the exterior of the Wren Building and the drawings of the elevations of Williamsburg buildings shown on the Bodleian Plate; drawings of interiors of buildings such as Lossing's sketch of the interior of the Apollo Room of the Raleigh Tavern, made in 1850, etc.

- -45-

- 6.Design characteristics.

- 7.Archaeological evidence and artifacts. (The Division of Architecture of Colonial Williamsburg has developed a chronology of pottery and porcelain which is of assistance in approximating the date period of usage of the fragments found on the site.)

ADDENDUM

Notes on changes and additions to the Pitt-Dixon House Report, suggested by Mr. S. P. Moorehead, March 9, 1950.

Corrections have been made on pages 2 and 3 of text and on illustration, p. 4.

In place of "obviously new work" use "later work." In the reconstruction of the house a vertical joint, an imbedded corner board was made between the front and later part. This was done with the purpose of indicating the late as distinct from the reproduction of the original part.

It seems desirable to further point out the basis for frame building to be found in the character of the excavated foundations. Brick superstructure is indicated by the thickness of foundations, namely 12" or more for masonry.

Indication is made of a variety of grades adopted for a reconstructed house, such as for an original paved cellar, as discovered by excavation; the cellar as reconstructed; and the modern sidewalk grade that adjoins the rebuilt house. Some of these grades have little to do with the original house. The restored grades are limited by conditions of the town which has adopted a system of grading that is often at variance with the old grades. There must necessarily be grade compromises based on conditions that surround a site.

Brickwork of reconstructed houses follow the original bond and brickwork appearance, only where exposed to view. Foundations, below the ground level have been made water-tight by the use of waterproofed concrete.

The materials, such as kinds of wood, used by the Colonial Williamsburg architects were not what the eighteenth century used, but what was considered the best modern material, available, for each purpose. Cypress was used in reconstruction of weatherboarding, because of its permanency, even though it may be known that some old weatherboarding was of oak or chestnut. Face nailing of siding has been generally used because of its suitability as a method for attaching weatherboarding, even though some of the old siding was not so applied.

The modillions used as a part of the exterior cornice stems from photographic evidence. Old photos show a modillion cornice and this is believed to be original or a replacement of the cornice in its first form.

Corner boards appear on reconstructed houses, not only on outer corners, but where an addition has been made, as for example, when a house has been lengthened. The Travis House expresses the episode of its lengthening by the placing of a corner board strip between what was deemed original, and what was of later date.

The window frames are fashioned by the mill so as to appear to be mortised, tenoned and pegged. In reality they are not joined together in that manner. Doors have the benefit of modem millwork methods, but they resemble doors of the eighteenth century. Muntins are a clue to the age of a building, since their profile changes from decade to decade. Old contours are usually followed, however.

Examples of muntins:

- Powder Magazine muntins are new, since no old ones existed to serve as a model.

- President's House muntins are a very late replacements of originals, lost in the Revolutionary fire. The Pitt-Dixon House muntins resemble closely the profiles of muntins of Captain Orr's dwelling.

Window Frames . These were built up of separate parts so as to appear like solid ones, where exposed to view.

The basement grilles of the Pitt-Dixon House differ from those of the Dr. Barraud House, since the latter had some bars of iron. The resemblance to the basement grilles of the Nicholson House on York Street, where bars are uniformly of wood, is more appropriate.

The Pitt-Dixon and the Mayo House, which originally stood on the north side of York Street, are strikingly alike in general appearance -- as shown by photographs. The photograph of the Mayo House in the Coleman Collection should be consulted to note similarities.

GENERAL

Information concerning the policy for the use of old materials, such as flooring, hardware, lighting fixtures, etc., can be had by reference to the Architectural Records files.

The interior of the house is not treated as a complete restoration. There were additions made for modern convenience such as modern heating and plumbing. The use of a cornice in the hall and chair railing in the dining room was without recorded precedent for the house. However, such details for the colonial house of this class, were customary.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Files of the Department of Research, Colonial Williamsburg.

- Files of the Department of Architecture, including photographs, drawings, records, and architectural fragments.

- Research Report, Pitt-Dixon House. Block 18, Lot 47, signed H.D. Farish, summer of 1940.

- Deeds, Wills, Inventories and other property records in the Department of Research and Records, Colonial Williamsburg.

- Files of the Virginia Gazette, with use of the Virginia Gazette Index for persons, property, buildings and other subjects.

- Archaeoloigical Drawings of area on Block 18, Lot 47, titled: Foundations, Pitt-Dixon House, made by James Knight, dated August 18, 1932.

- Architectural Reference Files

- Swem's Index with reference to individuals, events, building practices and materials.

- The Frenchman's Map

- Files of photographs and measured drawings, as a source of precedent used in reconstructing features of the house.

- Plans and Working Drawings of the house from files of the Department of Architecture, Colonial Williamsburg.

- Handbooks of the eighteenth century as basis for and as a check on building practices and materials of the eighteenth century in America.

- Insurance Policies relating to the property.

- Correspondence in General Files and of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, pertaining to the Pitt-Dixon House.

- Progress Photographs, taken as a record of work done in excavation, stripping the house, also as a step-by-step process of construction and restoration.

- Reminiscences of old residents of Williamsburg, notably Mr. Charles and Mrs. Victoria Lee. -47-

- Old photographs of Williamsburg in the Coleman Collection.

- Williamsburg town maps, near 1800, including the Estelle Smith, Annie Galt and Bucktrout Maps.

- Examination of artifacts sifted from the site.

- Visit to the house for verification of dimensions and of notes.

- Tyler, L. G. Williamsburg, the Old Colonial Capital. Richmond, 1907.

- Goodwin, Rutherfoord, Williamsburg in Virginia. Williamsburg, 1940.

- Blanton, Wyndham B. Medicine in Virginia in the eighteenth century. Richmond, 1931.

- de Graffenried, Thomas P. History of the de Graffenried Family. Published by the author, n.p. 1925.

INDEX

- ACT of 1705

- 4, 5, 7, 8

- "Antique" materials listed

- 29

- Approved Methods of Restoration

- 26

- Archaeological evidence

- 15

- Architectural Records Files

- 15

- BALUSTERS

- 30

- Illustrated

- 30

- Baseboards

- 29

- Basement Kitchen

- 3

- Basement Kitchens, examples of

- 3

- Basement window grilles

- 23, 24

- Bibliography

- 46, 47

- Blair, John, House

- 18

- Blair's Storehouse

- 6

- Blandfield

- 18

- Bond, brick

-

- English & Flemish

- 15

- Books published by Virginia Gazette

- 12

- Bracken House

- 21, 22, 23, 24

- Brickwork

- 14-17

- Brush-Everard House

- 2

- Builder's handbook

- 30

- Bulkhead

- 22

- CARTER'S Grove

- 18

- Carter-Saunders House

- 3

- Chair railing

- 29

- Charles, John S.

- 2, 5

- Chimneys

- 16

- Cogar, James, house of

- 20

- Coke-Garrett House

- 23

- Coleman Collection

- 2, 5, 6

- Composite plan of house

- 4

- Corner boards

- 21

- Cornice end boards

- 20

- Illustrated

- 21

- Cornice, main

- 20

- Cornice of rear

- 20

- Cornwallis, Lord

- 12

- Declaration concerning John Hunter

- 12

- "Covings"

- 31

- DATING of house

- 7

- Dating of houses

- 44, 45

- Death of Sarah Pitt

- 11

- Definitions of terms

- 42, 43

- De Graffenried, Christopher, I

- De Graffenried, Christopher, II

- Description of house

- 2

- Design basis of house

- 3

- Dixon, John

- 1

- Door paneling

- 36-37

- Doors

-

- Exterior

- 25

- Door schedule, exterior

- 36

- Door schedule, interior

- 36, 37

- Door trim listed

- 36-37

- Dormers

- 21, 22

- Downspouts

- 17

- EARLIEST dwelling of Williamsburg

- 9

- Exterior of house

- 14-25

- FACING, types of

- 20

- First Theatre

- 18

- Floors

- 29

- Flushboarding

- 20

- Foundations, new, of concrete

- 15

- Grade levels

- 16

- Foundations, old

- 7, 14

- Franklin, Benjamin

- 11

- Freeman, Joseph

- 8

- Frenchman's Map

- 4, 7, 28

- Showing house & outbuildings

- 7

- GABLES, treatment of

- 21

- Galt, Annie, House

- 23

- Goodwin, Rutherfoord

- 5

- Green, Sarah,

- see Pitt, Sarah

- Green, William

- 10

- Grilles, basement

- 23-25

- Gutters and guttering

- HANDRAILING

- 30

- From handbook, illustrated

- 30

- Hardware

- 38, 39

- Reproduced from old examples

- 28

- Hinges

- 38, 39

- Hungar's Glebe, chimney cap of

- 16

- Hunter, William I

- 1, 11

- Hunter, William II

- Hyde, Samuel

- 8

- INDIANA Limestone

- 17

- Interior discussed

- 26-35

- JONES, Thomas

- 8

- KENDREW, A. E.

- 14

- Letter concerning foundations

- 14

- LIGHTFOOT House

- 20, 25

- Location of house

- 1

- Locks, doors

- 38, 39

- Ludwell-Paradise House

- 3

- MANTELS

- 29

- Market Square Tavern

- 21

- Mayo House

- 29, 30

- Montpelier, Charles City County

- 23

- Moody House

- 20

- Moorehead, S.P., drawing by

- 16

- "Much-marrying Sarah"

- 10

- Muntin bars

- 23

- Precedent for

- 23

- NAME, derivation of

- 1

- New Bern, founding of

- 9

- Newel post, rear porch, illustrated

- 22

- OCCUPANTS of house

- 1, 10

- Orr's Dwelling, Captain

- 2

- Orrell House

- 21

- Outbuildings described

- 3

- Outbuildings of lot 47

- 2

- Oyster shell lime

- 15

- PACKE, Captain Graves

- 10

- Packe, Richard

- 10, 11

- Packe, Sarah

- see Pitt, Sarah

- Painting

- 40, 41

- Pallard House

- 20

- Paneling, "antique"

- 35

- Parks, William

- 11

- Death of

- 11

- Personalities Associated with house

- 9-13

- Pitt-Dixon House

-

- Basement Kitchen

- 3

- Basis for its design

- 3

- Cellar underneath

- 3

- Compared with other dwellings

- 2, 3

- Composite plan of

- 4

- Dating of

- 7

- Derivation of name

- 1

- Described in Virginia Gazette

- 3

- Description of

- 2

- Description of type

- 25

- Destroyed by fire

- 2, 13

- Early photographs of

- 2, 6

- Exterior reconstruction

- 26

- Exterior treatment discussed

- 14-25

- Features of

- 3

- Interior

- Interior treatment discussed

- 26-35

- Its original form

- 3

- Location of, in Williamsburg

- 1

- Native in character

- 2

- Notable occupants

- 9-13

- Occupants

- 1, 10

- Old foundations

- 7

- On old maps

- 1

- Outbuildings described

- 3

- Outbuildings of

- 2

- Photograph of exterior

- 1

- Planned as dwelling

- 26

- Plan of first floor illustrated

- 27

- Plan of second floor illustrated

- 28

- Plot plan of

- 1

- Roof

- 19

- Sale and resale

- 8

- Size of

- 4, 5, 26, 27

- Pitt, Dr. George

- 1, 9, 10

- His career

- 10

- Pitt, Sarah

- 10, 11

- Plan Type

- 26

- Planned as dwelling

- 26

- Plan of Frenchman's Map

- 28

- Plan of house

- 4

- PLans as reconstructed

- Plot plan, lot

- 47

- Porches

- see stoop

- Powell-Hallam House

- 25

- President's House

- 18

- Purbeck stone

- 17

- Purdie, Alexander

- 12

- RAILING, rear porch illustrated

- 22

- Rakeboards

- 21

- "Recollections of Williamsburg," John S. Charles

- 2, 5

- Roof

- 19

- Rosewell

- 35

- Royle, Joseph

- 12

- ST. John's House

- 25

- Shield, James

- 7

- Shurcliff, Arthur A.

- 14

- Shutters

- 25

- "Sign of Rhinoceros"

-

- Location of

- 10

- Sills, window

- 24

- Size of house

- 4, 5

- Slate for roofing, reference to

- 19

- Spencer Lane House

- 21

- Spotswood, Governor

- 9

- Stairway

- 29

- Steps, Pitt-Dixon

- 18

- Stone masonry

- 17-19

- Stone nosings of Virginia compared

- 18

- Stonework

- 19

- Stoops

- 22

- Newel post and rail of rear porch, illustrated

- 22

- "Sufficient house"

- 5

- TIMSON, House

- 31

- Timson, William, first owner of lot 47

- 7, 8

- Travis House

- 20, 21

- Trim, exterior

- 21