Governor's Palace Kitchen Architectural Report, Block 20 Building 35Originally entitled: "Architectural Report Governor's Palace Kitchen Block 20, Building 35"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1467

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

GOVERNOR'S PALACE KITCHENBlock 20, Building 3J

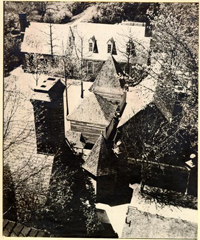

OUTBUILDINGS WEST OF GOVERNOR'S PALACE. THE KITCHEN AND SCULLERY ARE AT THE TOP OF THE PICTURE, THE GUARD HOUSE AT THE LOWER LEFT AND THE LAUNDRY AT THE RIGHT CENTER. THE BUILDINGS IN THE MIDDLE GROUND, STARTING AT THE LOWEST, ARE THE HEXAGONAL BUILDING (POSSIBLY A BATH HOUSE), THE WEST WELL, THE SALT HOUSE AND THE SMOKE HOUSE. (Photo, Herbert Matter)

OUTBUILDINGS WEST OF GOVERNOR'S PALACE. THE KITCHEN AND SCULLERY ARE AT THE TOP OF THE PICTURE, THE GUARD HOUSE AT THE LOWER LEFT AND THE LAUNDRY AT THE RIGHT CENTER. THE BUILDINGS IN THE MIDDLE GROUND, STARTING AT THE LOWEST, ARE THE HEXAGONAL BUILDING (POSSIBLY A BATH HOUSE), THE WEST WELL, THE SALT HOUSE AND THE SMOKE HOUSE. (Photo, Herbert Matter)

The Palace Kitchen was reconstructed by the Williamsburg Holding Corporation under the direction of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, Architects. Walter Macomber was at this time in charge of the Williamsburg office of the architects.

Reconstruction was started in January, 1933

Reconstruction was completed in August, 1933

Persons who worked on the project:

- The Research Report on the Governor's Palace and its Outbuildings was compiled under the direction of Harold R. Shurtleff. The report is dated May, 1932.

- The archaeological investigations were conducted by Herbert Ragland.

- Singleton P. Moorehead was Job Captain.

- The working drawings were made by Singleton P. Moorehead, Lucien Dent, Richard A. Walker and J. M. Townsend.

This report was written by Singleton P. Moorehead and dated February 15, 1934. It was revised, edited and illustrated by Howard Dearstyne in June, 1951.

GENERAL NOTES

See General Notes on Governor's Palace Outbuildings for discussion of the relation of this structure to the general layout of the whole Palace group.

QUESTION OF LOCATION OF PALACE KITCHEN

The question arose in interpreting the Palace specifications, which call for a dwelling, kitchen and stable, whether the Kitchen might not have occupied one of the advance buildings and the Stable the other. For the arguments for and against this hypothesis see the report of the Department of Research and Record entitled "Governor's Palace Kitchen," December 8, 1931. Besides the points mentioned in this report there is the fact that Edmund Randolph was known to have been living in the West Flanking Building at a time when Humphrey Harwood was making repairs on the Kitchen. The latter is treated in the records in such a way as to indicate that it existed prior to the repairs. It is likely, therefore, that this is the old Palace Kitchen and that the Kitchen and the West Flanking Building are not the same structure. Its location, moreover, has been established by existing foundations. See a detailed discussion of this point in 2. a letter written by H. D. Shurtleff on November 13, 1931, to Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, Boston. The fact that the records constantly refer to the advance buildings as offices* is given weight by the finding of a neatly-made vault, apparently of the original period of building, below the ground in the East Flanking Building. This precludes the possibility of reference to the structure as a stable, especially since later evidence tends to place it in the northeast# area of the Palace layout.

EVIDENCE THE KITCHEN WAS SEPARATE FROM ADVANCE BUILDINGS

The weight of argument seems to indicate the Kitchen and Stable as being separate from the advance buildings. Mr. Bright, whose family once lived in the West Flanking Building, recalls their descriptions of the fine woodwork therein. This, further, lends weight to the West Advance Building as being used for a purpose other than that of a kitchen since typical Virginia kitchens of the period do not exhibit more than the plainest interiors.

"OUTHOUSES BELONGING TO KITCHEN"

The Botetourt inventories mention "Outhouses Belonging to the Kitchen." In the course of a careful examination of the existing foundations, the nature of certain items became obvious and these fell, likewise, into the general category of "Outbuildings Belonging to the Kitchen." Chief of

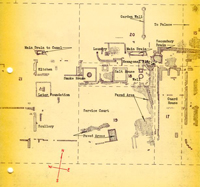

ARCHAEOLOGICAL DRAWING OF FOUNDATIONS UNCOVERED SOUTHWEST OF GOVERNORS PALACE BY HERBERT S. RAGLAND BETWEEN 1930 AND 1932. This plan should be compared with the layout of

the service buildings as reconstructed (page 3a). Drawing made by James M. Knight, Dec. 31, 1932

3.

these were the Smoke House foundations. It was recorded that Edmund Randolph built a brick smoke house. The foundation in question was for a frame structure and of an early type. For these reasons it was felt to be of the Botetourt inventory period at least, if not earlier. Nearby were heavy foundations for two brick buildings. In the inventory the Scullery and Kitchen are itemized side by side. The sizes of these foundations, which were fragmentary, were determined by fragments of brick gutters which indicated the distances the walls extended.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL DRAWING OF FOUNDATIONS UNCOVERED SOUTHWEST OF GOVERNORS PALACE BY HERBERT S. RAGLAND BETWEEN 1930 AND 1932. This plan should be compared with the layout of

the service buildings as reconstructed (page 3a). Drawing made by James M. Knight, Dec. 31, 1932

3.

these were the Smoke House foundations. It was recorded that Edmund Randolph built a brick smoke house. The foundation in question was for a frame structure and of an early type. For these reasons it was felt to be of the Botetourt inventory period at least, if not earlier. Nearby were heavy foundations for two brick buildings. In the inventory the Scullery and Kitchen are itemized side by side. The sizes of these foundations, which were fragmentary, were determined by fragments of brick gutters which indicated the distances the walls extended.

METHOD OF DETERMINING SIZE OF KITCHEN ITS ROOMS

By computing the floor space necessary to accommodate the number of rooms, stories, and furnishings as given in the Botetourt inventory, it was possible to arrive at a kitchen size and mass which agreed with the typical, known kitchens of brick in Tidewater Virginia in the Colonial period. The inventories mention the Kitchen, Servant's Hall, Cook's Bed Chamber in sequence as probable division of the Kitchen. At another point they mention the Gardener's Room and again the Servant's Hall. It is possible that the Gardener's Room may have been in the Kitchen., but this conclusion depends on the method of reading the inventories.

REASONS FOR SEPARATING KITCHEN AND SCULLERY

As mentioned above, the two heavy foundations were not of similar thickness and did not line up exactly. At a mid point between the extremities -- which were intact at the northwest and southwest corners -- were the remains of a gutter and drain, apparently on the original ground surface. This led to the decision to separate the buildings by a passage at this point, and was a definite factor, therefore, in the determination of the lengths of the respective

3a.

LAYOUT OF THE OUTBUILDING GROUP SOUTHWEST OF THE PALACE. THE PALACE ITSELF IS NOT SHOWN BUT LIES JUST WEST OF THE UPPER PART OF THE RIGHT EDGE OF THE SHEET.

4.

structures -- making the Kitchen larger then the Scullery and causing it to be called this.

LAYOUT OF THE OUTBUILDING GROUP SOUTHWEST OF THE PALACE. THE PALACE ITSELF IS NOT SHOWN BUT LIES JUST WEST OF THE UPPER PART OF THE RIGHT EDGE OF THE SHEET.

4.

structures -- making the Kitchen larger then the Scullery and causing it to be called this.

BRICK SIZE SMALLER THAN THAT OF PALACE

The brick in the larger of these foundations is of a smaller size than that of the main Palace building. No reason is apparent for this other than the fact that the smaller outbuildings may have been built of a different brick than in the main structure. However, the brick and mortar appeared to be of an early type, and they were laid in English bonds as were the foundations of the main and flanking buildings.

IDENTIFICATION OF SALT HOUSE FOUNDATIONS

No other portion of the Palace layout exhibits the number and variety of existing foundations as the southwest or Kitchen Service Court, nor in the Botetourt inventories is there any group itemized which is so extensive and varied. The identification by inspection of the Smoke House foundation permitted the identification of the Salt House foundations with reasonable certainty. These two items of the "Outbuildings Belonging to the Kitchen" of the inventory were thus fairly well established with the result that the whole group was determined.

LAYING OUT OF NEW FOUNDATIONS

The mass-relation of fenestration in brick surface to finish first floor and watertable follow, insofar as difference in plan shape permits, the brick kitchen dependency of King's Mill, James City County an early structure of the eighteenth century. The new foundations were laid out on the lines indicated by the existing old foundations. The latter foundations, however, were in such bad condition as not to allow rebuilding on them. After carefully recording 5. them by drawings and photographs and after the batter boards and lines for the new building were erected, they were removed.

EXPOSED PARTS OF KITCHEN FOLLOW OLD PRECEDENT; UNEXPOSED BUILT WITH MODERN METHODS

In general, all exposed surfaces of the building as constructed follow local eighteenth-century methods and precedent in design, material and texture. Unexposed or hidden portions are built of stock material in modern building techniques so as to be as permanent as possible, since to construct these parts in the eighteenth-century manner would not have resulted in as permanent a structure and the cost would have been prohibitive.

All exterior woodwork except shingles and doors are painted Cabot's Double White, slightly tinted. The result is a slightly buff cream color. Shingles left natural to weather dark gray. Doors painted.

All colors used have bean authenticated by various examples of eighteenth-century paint colors used locally. Authorities at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and elsewhere have likewise been consulted and all information checked against items in eighteenth-century documents or transcripts thereof on file in the Department of Research and Record.

EXTERIOR

CHARACTER OF BRICKWORK AND ITS MANUFACTURE

Face brick was made by hand of local clay, burned in such a manner as to make it similar in color, texture, shape, density, etc., to existing brickwork on the site. The glazed brick resulted automatically from firing in accordance with the conventional eighteenth-century method and are like those from the original structure found on the site. The mortar for the face brick was made of local yellow sand and oyster shell lime so as to be in color, texture, and effect the same as the original mortar found on the site. In its early stages, after being applied, this is a yellow buff which gradually bleaches through weathering and chemical action. No attempt was made to "fake" age -- the brick and mortar on exposed portions of the Kitchen have not been treated in any manner since the building was constructed. The tooling of the joints was copied from that on the existing foundations on the site.

HEART PINE USED WHEREVER POSSIBLE FOR WOODWORK

Heart yellow pine was the great building material used locally in the eighteenth century. It was used wherever possible in this building. But where heart could not be procured other woods were employed, because yellow pine other than heart gives an ugly, grained surface not at all in keeping with the surface of heart pine. Wherever other woods were used, the following notes indicate this fact.

EDMUND RANDOLPH'S BRICK SMOKE HOUSE AND DAIRY

The argument has been put forth that the foundations which existed, which we believe to have been those of the Kitchen and Scullery, may, on the contrary, have been of

7.

the Dairy and Smoke House built by Humphrey Harwood for Edmund Randolph. The existing west wall of the Scullery is too long for either of these, nor did the original ground surface indicate the usual depressed floor common to such structures of the end of the eighteenth century

when Harwood, by the records, built them. Furthermore, the very heavy walls of the old Kitchen foundations would not be typical of a smoke house or a dairy of brick. In addition, brick dairies and brick smoke houses are unusual in the eighteenth century.

7.

the Dairy and Smoke House built by Humphrey Harwood for Edmund Randolph. The existing west wall of the Scullery is too long for either of these, nor did the original ground surface indicate the usual depressed floor common to such structures of the end of the eighteenth century

when Harwood, by the records, built them. Furthermore, the very heavy walls of the old Kitchen foundations would not be typical of a smoke house or a dairy of brick. In addition, brick dairies and brick smoke houses are unusual in the eighteenth century.

For further notes and facts see reports and archaeological drawings of the remains of the original building prepared by H. S. Ragland for the Department of Research and Record.

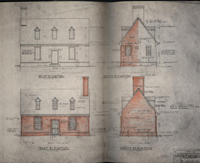

EAST ELEVATION

SHINGLES AND METHOD OF APPLYING THEM

Hand split cypress shingles, procured and hewn locally after general local eighteenth-century precedent. The framing, sheathing and application of builders' paper follow modern roofing methods. Typical eighteenth-century ridge-combing of shingles was employed. Flashing was used on all parts of the roof where it was necessary but it was hidden from the eye. Framing and sheathing of common local pine and modern manufacture. At dormers shingles cover joint in roof by swirls as at original Kiskiak, York County.

DORMER WINDOWS

These are adapted closely from local examples of the period, such as, (1) an early brick house between Saluda and West Point; WINDOWS (2) original dormers at Kiskiak; (3) original dormers at Warburton House, an early brick structure in James City County. 8. The frames and sash were morticed, tenoned and pegged as in these examples. The frames and trim were made new of heart yellow pine. All exposed woodwork was molded to detail by modern milling methods, following the above examples in design. The unexposed framing, sheathing, etc., was constructed of stock pine material by modern carpentry methods. The sheathed cheeks were insulated by double-thickness mineral wool. Sash was made of white pine, heavily-molded, in the local eighteenth-century manner and glazed with English crown glass, made by the old disc method to simulate the wavy eighteenth-century type of window glass used locally. The top sash are fixed and the bottom movable as in the prototypes listed above.

CORNICE AND ITS PRECEDENT

The exposed members of the cornice are a combination of features similar to those found in the following old examples: (1) brick kitchen at Stratford, Westmoreland County; (2) Kitchen of Carter's Grove, James City County; (3) brick kitchen, Westover, Charles City County. The material is new, of heart yellow pine, run to detail by modern milling methods. The blocking for the cornice follows modern building practice, since it is Restoration policy to use modern building methods in the construction of hidden framing. For cornice and boards, see North Elevation , page 13. Contrary to eighteenth-century usage, a crack between facia and soffit boards was left to provide ventilation of roof spaces. Since the roof is not laid in the customary open eighteenth-century way on spaced roofers without paper, but in the modern, sealed manner, it became necessary to allow an air circulation for reasons of permanency. It is not a noticeable feature and does not mar the eighteenth- 9. century character of the cornice.

GUTTER AND LEADER

None at eaves. Brick gutter at ground line built which matches gutter type as indicated in fragments of ancient gutter found along foundation walls. Patches of old brick paving gave evidence of a paved court yard and this was so treated. The character of the gutter justified the carrying of this paving up to its lip or outer edge. A cast iron drain grille at intervals carries off the water collected by the gutters - a concession to modern drainage methods.

WALL SURFACE

Brick, laid in Flemish bond of brick of the same size as those in existing foundations. Glazed headers are random, after the manner of the wall surface of the advance buildings as these are shown in early photos. The mortar of the outside 4" of the wall is of local sand and oyster shell lime, the joints being tooled to match the existing old mortar points of the foundations of the main part of the Palace foundations and to copy their texture. The headers and stretchers at the corners above the watertable are ground brick.

PORCH

None. A new Portland stone step was used at the front entrance with molded nosing copied frown fragments of old steps found at the site of the Kitchen group. The testate of the stone is also similar to that of the old steps. The step is placed on a brick foundation which, since it is hidden from the eye, is made of modern, stock material in accordance with current building methods.

FRONT DOOR

Of a type exemplified by the following eighteenth-century brick kitchens: (1) King's Mill, James City County; (2)Carter's Grove, James City County. The trim is a typical double 10. molded type and the door is a typical six-panelled one with the customary head and bevel mold. These moldings are so customary in eighteenth-century local work as to preclude the necessity of citing individual examples. The frames, door stiles and rails are mortised, tenoned and pegged, as in eighteenth-century work. All the woodwork was run by modern millwork methods. The frames are of heart yellow pine, the trim of yellow pine, and the door of white pine. All this material is new. The brick arch was gauged and laid in lime-putty mortar. The jambs have ground headers and stretchers. The watertable was relocated to line up with the finished first floor as in King's Mill kitchen or dependency, which places the door in such a position that it cuts through the watertable. At the head of the door, steel angles are inserted to bear the backing-up brick. These were used since they are hidden and far more permanent than the wood headers common to eighteenth-century practice. See General Notes , page 5, on hidden structure. Concealed flashing likewise was inserted at the head as an aid to permanency. The frames are anchored to the wall with galvanized iron strips which are entirely hidden. This is again a modern method of building to insure permanency.

WINDOWS

See note under Front Door regarding the relation of watertable to the first floor. The location of the watertable at the floor level brings windows closer to it than in the examples ordinarily used as precedent. The long, narrow opening and thin head arch are employed as at King's Mill. The arch was gauged brick, ground on the sides and front and laid in lime-putty mortar with very thin points. The jambs 11. have headers and stretchers ground on the front. All woodwork was made new to detail by modern milling methods. The frames, sill and trim are mortised, tenoned and pegged after the above precedent and are of heart yellow pine. The sash is of white pine, a concession to permanency and ease of working, since it is superior to the yellow pine customarily used for sash in the eighteenth century. Glazing as for Dormer Windows , page 7. The frames are attached to the brickwork by hidden galvanized iron anchors and are flashed at the heads with hidden copper flashing according to modern building practice. The brick at the head is further supported by steel angles hidden within the construction. This is a departure from eighteenth-century building methods in which wood headers were used and is a concession to modern building knowledge. This construction is hidden and made permanent, and was used for these reasons.

The top sash are fixed which was common practice locally in eighteenth-century structures. The lower sash are movable, being hung on sash cords, with apple wood pulleys and lead weights. Many instances of this arrangement were found in Williamsburg in the course of restoring colonial buildings.

SHUTTERS

None were used since this is a brick structure and it was not in accordance with usage to have them on brick buildings*.

BASEMENT WALL

The building has no basement. Below the watertable the wall is laid in English bond, as were the existing foundations, with random glazed headers as in the existing foundation walls 12. of the advance and main buildings. See notes under Windows , page 10, for relationship of first floor to watertable, and the precedent therefor. The watertable was ground to a bevel, as in usual precedent examples and laid in Flemish bond. The profile follows the type of that of fragments of old watertables found on the site during the excavations.

CHIMNEY

The chimney was designed to accommodate the necessary flue areas demanded. by the great kitchen fireplace and the smaller one on the second floor. This gave a section similar to the chimney of the Stratford, Westmoreland County kitchen. A simile type of cap, locally common in the eighteenth century was applied. This was adapted after chimney caps of (1) the Brush-Everard Kitchen, Williamsburg; (2) the Richie House, Tappahannock; and (3) the Greenhow-Repiton Brick Office, Williamsburg. The corner headers and stretchers were ground on the face as at Stratford.

BARGE BOARDS CORNICE END BOARDS, CORNER BOARDS

See North Elevation , page 14.

GENERAL NOTES

Only exposed portions of the building were constructed so as to appear as these features did in the eighteenth century. Hidden framing and brickwork, concrete floor slab, etc., were built in accordance with modern methods with modern, stock materials.

NORTH ELEVATION

SHINGLES See East Elevation , page 7.

DORMER WINDOWS

Ditto.

13.CORNICE

Ditto.

GUTTER AND LEADER

None.

WALL SURFACE

Same as for East Elevation , page 9. At certain points headers were left out to a depth of 4". This was common practice in eighteenth-century brick walls, but for what reason we do not know*. Carter's Grove and its dependencies are a notable example of such treatment. Certain brick were left out, with holes leading to kitchen fireplace throat for added air, if such were needed. There holes are temporarily blocked.

PORCH

None.

FRONT DOOR

None.

WINDOWS

None. This was usual at fireplace ends of brick kitchens as is seen in examples, such as (1) the Westover Kitchen, Charles City County; (2) the Carter's Grove Kitchen, James City County; and (3) the brick kitchen on the Smith Place, Suffolk, Virginia.

SHUTTERS

None.

BASEMENT WALL

See East Elevation , page 11.

CHIMNEYS

See East Elevation , page 12. The north face of the chimney sits back of the north wall 4 ½" or one brick width, allowing the barge or rake board to reach the roof peak. This was typical of King's Mill dependency and Carter's Grove Kitchen. On the face of the chimney a modified pattern of glazed headers was used which was adapted from that of the Carter's Grove Kitchen.

14.BARGE BOARDS CORNICE END BOARDS, CORNER BOARDS

The rake board is tapered toward the peak, a typical treatment in this locality for,eighteenth-century work. The cornice stop is an adaptation from Tuckahoe, Goochland County. Rakes and cornice stops were made new to detail from heart yellow pine and run by modern milling methods.

WEST ELEVATION

SHINGLES

See East Elevation , page 7.

DORMER WINDOWS

Ditto.

CORNICE

Ditto.

GUTTER AND LEADER

See East Elevation , page 9. Since a brick terrace was employed on this side by the Landscape Department, no gutter was needed, the grading of the paving being so adjusted as to serve as a gutter.

WALL SURFACE

See East Elevation , page 9.

PORCH

Ditto.

FRONT DOOR

Ditto.

WINDOWS

Ditto.

SHUTTERS

Ditto.

BASEMENT WALL

Ditto.

CHIMNEYS

Ditto.

BARGE BOARDS END BOARDS CORNER BOARDS

Ditto.

GENERAL NOTES

Ditto.

SOUTH ELEVATION

SHINGLES

See East Elevation , page 7.

15.DORMER WINDOWS

Ditto.

CORNICE

See East Elevation , page 8.

GUTTER AND LEADER

The passage between the Kitchen and Scullery was paved to act as a gutter for adjacent buildings as well as the nearer portion of the court yard. See General Notes, page 3.

WALL SURFACE

See East Elevation , page 9, and North Elevation , page 13.

PORCH

None.

FRONT DOOR

None.

WINDOWS

Two 8-light windows. All notes regarding brickwork, sash, frame, trim, glazing and construction are the same for these as for the 18-light windows on the East Elevation , page 10. Although eighteenth-century brick kitchens do not usually have end windows, two examples may be mentioned: Carter's Grove Kitchen and that at Ampthill, Chesterfield County. Since end windows customarily receive less emphasis in colonial architecture of this locality than front or rear ones, the present windows were made to accommodate only eight lights.

SHUTTERS

None. See East Elevation , page 11.

BASEMENT WALL

Ditto.

CHIMNEYS

None.

BARGE BOARDS END BOARDS CORNER BOARDS

See North Elevation , page 14.

INTERIOR

GENERAL NOTES

See General Notes , page 2, for remarks on the Botetourt inventories which indicated the room arrangement here. The Kitchen at Stratford, Westmoreland County, and the dependency or kitchen at King's Mill, James City County, contributed many details. Notes gleaned from the Department of Research and Record report on Kitchens in Colonial Virginia were used to check most of the details employed by citing documentary precedent. The Kitchen at Marmion, King George County, likewise furnished certain precedent for the character of the detailing and finish, the doors, etc.

HEATING SYSTEM

Not typical of an eighteenth-century building, obviously, but now demanded by modern conditions. The heating of this building was provided in such a way as to be most unobtrusive--chiefly by concealing the radiation appertaining to a vacuum steam system below the window stools and behind the respective plaster walls. The steam heat is brought from the West Flanking Building in an insulated conduit below ground to a pit of concrete below the floor slab in the southeast corner of the structure. From this point the, various risers lead to

their respective radiation units in chases in the brick walls which conceal them. Concrete trenches convey the lines to the proper vertical locations of the risers. Access to this pit is provided in the Servant's Hall (see Floor

, page 22). The radiators have all been inserted in their positions, but the stools and baseboards have not been cut to receive the grilles.

16a

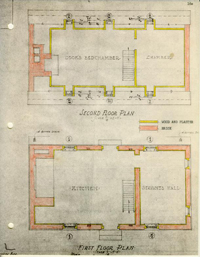

Floor Plans

17.

Thus the system has been installed, ready for use if so desired, but requiring the baseboard cutting for cold air intake return and the grilles in window stools for hot air exhaust.*

Floor Plans

17.

Thus the system has been installed, ready for use if so desired, but requiring the baseboard cutting for cold air intake return and the grilles in window stools for hot air exhaust.*

ELECTRICITY

For convenience, inspection by watchman or emergency, one base plug was inserted in the baseboard on the east wall of each room. These are controlled by a panel and plugs in the West Flanking Building. The plug plates were painted in with the baseboards to be as inconspicuous as possible.

FIRST FLOOR

FLOOR

Of brick, laid in sand on the concrete slab. An eighteenth-century character is preserved in all features exposed to the eye. Hidden portions were built according to best modern building practice. The concrete slab was necessitated by the fact that the ground was disturbed and filled in excavating and this would have resulted, without the slab, in dampness in the building. The concrete floor slab rests on the walls of the building which are lowered by their concrete footings to firm bearing soil. In the northern portion the footings extend deeply before carving to firm bearing.

Brick used in the building was old brick from the "Antique Warehouse." The brick in this collection is eighteenth-century brick gathered in larger or smaller lots from miscellaneous sources in the vicinity. The larger lots have been designated for use on fobs needing large quantities but the small lots have been piled like to like in size, 18. texture and color, forming a general "pool" where the identity, of the source of the individual brick has become lost or has been given up.

FLOOR NAILS

None.

BEAMS

The floor is a reinforced concrete slab spanning between the foundation walls. (See above for reasons dictating the use of concrete here.)

WALLS AND WALL COVERING

The walls are plastered with slightly rough texture to imitate the plaster finish current in the eighteenth century. The brick walls were strapped with 2 x 4's laid flat. These walls were kept slightly thinner than in the original structure so that they would present the same dimension as the old walls from the finished plaster on the inside to the finished exterior brick face. Although it was common practice in the eighteenth century to plaster directly on brick, it is not practiced now because this causes heavy condensation on the plaster, which would be injurious to the antique furnishings which are to be used in the building. The plaster is placed on metal lath which is hidden from the eye. Metal lath is superior to the wood lath used in the eighteenth century.

CEILING

Same type plaster as for walls. Same lath, for same reason.

BASEBOARD

Antique beaded wood base receives plaster just above the brick floor.

CHAIR RAIL

None. At time of furnishing the building, the decorators applied certain hook strips, etc, These are not part of the architectural contract and are treated elsewhere.

CORNICE

None.

19.PANELLING OR WAINSCOT

None.

MANTEL

None. Mantels were not common in eighteenth-century kitchens in this locality. Shelf space was provided by dressers and other furniture.

FIREPLACE AND HEARTH

The large fireplace was constructed after the examples of the Stratford Kitchen, Westmoreland County, and the King's Mill Kitchen, James City County, both of which were carefully measured. The back brick bonding of the plastered open throats of these examples was followed in this fireplace, as were the division of the chimneys into two flues and the arched fireplace heads. It was necessary to insert in each flue a metal louvre operated by rods above the eye level to close the flues when these are not in use and to protect the fireplace from the weather. Above the throat or smoke chamber, modern, stock Terra Cotta flues were inserted. Since they are hidden from the eye it was considered advisable to use this modern method which is superior to the eighteenth century type of small plastered flues.

No oven was built because it was felt, after a careful survey, that in the early eighteenth century they were rare in Virginia kitchens. This and the fact that the ovens which were found seemed to have been later additions, led to the conviction that the brick oven was introduced into eighteenth century Virginia kitchens during the latter portion of the century.* Space was allowed in placing the chimney breast,

HOUSEHOLD UTENSILS IN THE PALACE KITCHN. AMONG THE OBJECTS SHOWN ARE LADLES, DRAINING AND SKIMMING SPOONS, LONG-HANDLED FIREPLACE FORKS, A LANTERN, A CHANDELIER AND FOOT WARMERS. (Photo, Herbert Matter)

20.

nevertheless, for the future addition of an oven, if it seemed desirable to build this later. (see supplementary report on oven, p27a)

HOUSEHOLD UTENSILS IN THE PALACE KITCHN. AMONG THE OBJECTS SHOWN ARE LADLES, DRAINING AND SKIMMING SPOONS, LONG-HANDLED FIREPLACE FORKS, A LANTERN, A CHANDELIER AND FOOT WARMERS. (Photo, Herbert Matter)

20.

nevertheless, for the future addition of an oven, if it seemed desirable to build this later. (see supplementary report on oven, p27a)

At the right of the fireplace in the breast a void was provided. This was connected with the exterior by means of a duct formed by leaving out headers and screening the opening which was left thereby. Then at two points in the base of the throat or smoke chamber, vents were likewise provided to the void, which were temporarily blocked up with removable headers. These were provided to furnish fresh air to the fireplace when a fire is burning with the Kitchen doors and windows shut. So great is the suction of fresh air into the fireplace under normal burning conditions that the closing of the doors and windows would prevent proper combustion and fill the rooms with smoke and cause eddies and air currents to blow the ashes into the Kitchen. The two air intakes would help this condition were it necessary to build a fire and keep the doors and windows shut.

No hearth was provided since floor of the room is of brick.

WINDOWS AND WINDOW TRIM

For frames and sash, glazing and construction see Windows, East Elevation , page 7. Jambs are plastered and splayed, as is customary with untrimmed openings in brick buildings of the period in this locality. The stools are of 21. wood, run to detail, from old material from the "Antique Warehouse," and they are finished with the typical cyma mold of local colonial trim. For the concealed radiator under the stool and the grille in the stool, see Equipment , below.

CLOSETS

None.

DOORS AND DOOR TRIM

For the exterior door, see East Elevation , page 9. The jamb is plastered, as are the window jambs, but not splayed like the latter. This was customary in local eighteenth-century brick buildings. Door #3 to the Servant's Hall, a beaded batten door was adapted from one in an outbuilding of Marmion, King George County. The brick partition through which the door is cut is sealed with a flush wood jamb and simple trim. This method of trimming an opening in an interior brick partition was adapted from a similar case in the Paradise House, Williamsburg. This was required in the design because of the necessity of securing the brickwork with metal L's, which otherwise could not have been well concealed even with plaster. Since the partition wall was 13 ½" thick, a bored-in frame was more suitable and this in turn necessitated a modified trim to cover the point of the plaster with the wood reveal. Thus the method of trimming this door opening was governed by demands of modern construction, although the visible portions follow precedent. The door. itself was made from old material run to detail by modern mill methods. The battens were fixed by hand-wrought nails driven in five-spot pattern, a common practice in the eighteenth-century batten doors in this vicinity. The frame and trim was made of heart yellow pine, new and run to detail by modern mill manufacture.

22.METAL WORK

On entrance doors H. and L. hinges by local craftsman, hand-wrought after the eighteenth-century models procured locally from old structures. These are fixed to the door and frame with wrought nails. Brass escutcheon, iron rim lock, key brass knobs for same doors. These are antique colonial examples procured from local dealers. Door #3 . Same H. and L hinges; wrought iron hand latch from the same source as H. and L. hinges.

COLOR

Walls, ceiling, fireplace breast and all woodwork except the baseboard are whitewashed. See Department of Research and Record report on Kitchens in Colonial Virginia for precedent. The baseboard is painted black, as common practice in eighteenth-century colonial buildings.

EQUIPMENT

Under each window is a concealed vacuum steam radiator. A cutting in the baseboard and a metal grille in the stool permit the circulation of air necessary for the unit to function. These features are concealed as far as possible. For further discussion of the heating of the building, see General Notes , page 16. For Electricity see General Notes , page 17. At present the baseboard cutting and stool grilles are not inserted, as noted in General Notes , page 16.

SERVANT'S HALL

FLOOR

Same as for Kitchen , page 17. In the southeast corner is an access door to the heating pit which is made of antique flooring laid on two battens of old material. All this material is from the "Antique Warehouse" and is derived from miscellaneous sources.

23.FLOOR NAILS

None.

BEAMS

See Kitchen , page 18.

WALLS AND WALL COVERING

Ditto.

CEILING

Ditto.

BASEBOARD

Ditto.

CHAIR RAIL

None.

CORNICE

None.

PANELLING OR WAINSCOT

None.

MANTEL

None.

FIREPLACE AND HEARTH

None.

WIND0WS

See East Elevation , page 10, and Kitchen , page 20, for 18-light windows and South Elevation , page 15, for remarks on 8-light windows. The interior treatment for 8-light windows is the same as for 18-light, except that there are no concealed heat units under the stools.

CLOSETS

None.

DOORS AND DOOR TRIM

For door #3 to Kitchen, see Kitchen , page 21.

EQUIPMENT

See Kitchen , page 22. For electricity see General Notes , page 17.

GENERAL NOTES

This room was given its title from the Botetourt inventories. Its purpose, judging by the eighteenth-century meaning of its name, was for the preparation and arrangement of food before this was sent across the court to the dining room of the main building.

[Second Floor]

COOK'S BED CHAMBER

FLOOR

Of old heart yellow pine, procured from an old Virginia mill in Buckingham County. Although of a slightly later period than the Kitchen, the texture of the wood is similar to that of the wood used in the eighteenth century. The floor is laid in the colonial manner and given a natural finish without stain, wax or oil.

FLOOR NAILS

Machine-made cut nails with heads hand-wrought by local craftsman to simulate typical eighteenth-century nails of this locality. The nailing was done in accordance with eighteenth-century methods.

BEAMS

Modern stock foists. Since it is concealed, the framing is constructed according to modern methods of building.

WALLS AND WALL COVERING

Same as for Kitchen , page 18.

CEILING

Ditto.

BASEBOARD

Ditto.

CHAIR RAIL

None.

CORNICE

None.

PANELLING OR WAINSCOT

None.

MANTEL

None. It was common practice in colonial outbuildings in this locality to omit this feature in second floor fireplaces.

FIREPLACE AND HEARTH

The fireplace is small and follows closely the second floor fireplace over the kitchen at King's Mill.

WINDOWS

For their construction and precedent see East Elevation , page 10. The corner of the reveal is finished off with a narrow, beaded corner board, typical of nearly all eighteenth-century 25. dormers in a 1 ½-story building of the period in this vicinity. The stool is the same as for the first floor windows. See Kitchen , page 20. See the same reference for the concealed head unit, etc., below the stool.

CLOSETS

None.

DOORS AND DOOR TRIM

Door #4 to Chamber. Same type door and of same material as #3. See Kitchen , page 21. The trim is flat and beaded and made of heart yellow pine to detail by modern mill methods. This type trim and frame are typical of local eighteenth-century building practice in minor or small buildings, or in larger buildings at unimportant openings. (Marlfield, Gloucester County). Hinges are H. & L., the same as those used in the first floor entrance room. See Kitchen , page 22.

Wrought iron latch same as on door #3.

COLOR

Same as for Kitchen , page 22.

EQUIPMENT

See General Notes , page 16, and Kitchen , page 22. For Electricity, see General Notes, page 17.

GENERAL NOTES

The size of this room conforms to the size suggested by the list of furnishings as itemized in the Botetourt inventory, dust as the size of the Kitchen was indicated as larger than that of the Servant's Hall.

CHAMBER

FLOOR

As for Cook's Bed Chamber , page 24.

FLOOR NAILS

Ditto.

BEAMS

Ditto.

WALLS AND WALL COVERING

Ditto.

26.CEILING

Ditto.

BASEBOARD

Ditto.

CHAIR RAIL

Ditto.

CORNICE

None.

PANELLING OR WAINSCOT

None.

MANTEL

None.

FIREPLACE AND HEARTH

None.

WINDOWS

See Cook's Bedchamber and references thereon, page 24.

CLOSETS

None. A scuttle was provided for the convenience of access to roof space. This was made to detail of new heart yellow pine by modern mill methods. It follows the precedent of a similar feature at Marlfield, Gloucester County.

DOORS AND DOOR TRIM

See Cook's Bed Chamber and references thereon, page 25.

COLOR

Same as for Kitchen , page 22.

EQUIPMENT

See Cook's Bed Chamber , page 25.

LADDER

PAINTING

The stringers and stairwell trim are white washed. The wood treads are left natural, with the surface untreated.

RISERS AND TREADS

Of old heart yellow pine from Antique Warehouse (miscellaneous sources). No risers since this is a ladder. The old material was worked to detail by modern manufacturing methods.

NEWEL POST AND HANDRAIL

None.

BALUSTERS

None.

STRINGER, STRING BOARD & STRING BOARD ORNAMENT

Heavy, beaded wood stringer, adapted closely from typical ladder examples in (1) Tucker House, Williamsburg, and (2) 27. Smith's Kitchen, Suffolk. The treads are tenoned into the stringers. The stringers are of old heart pine from the Antique Warehouse (miscellaneous sources), run to detail by modern mill methods.

LANDING

The trim around the second floor opening for the ladder is made to detail by modern mill manufacturing methods of old material (heart yellow pine) from the Antique Warehouse (miscellaneous sources). It resembles typical local colonial trim found in smaller houses of the period.

BASEMENT

No basement was indicated by the old foundations and none was put in new building. For floor construction, heating trenches and pit, see General Notes , page 16, and Kitchen page 17.

FIREPLACE OF GOVERNOR'S PALACE KITCHEN SHOWING COOKING UTENSILS REQUIRED IN THE PREPARATION OF A MEAL IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

FIREPLACE OF GOVERNOR'S PALACE KITCHEN SHOWING COOKING UTENSILS REQUIRED IN THE PREPARATION OF A MEAL IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

Footnotes

Putlog, pieces of Timber, or short Poles, (about seven Feet long) used by Masons and Bricklayers in building of Scaffolds to work on. The Putlogs are these pieces which lie horizontal to the Building, one end lying into it. And the other end resting on the Ledgers; which are those pieces that lie parallel to the side of the Building.

Ordered that the oven in the Glebe Kitchen be taken out and a Closet Made in that End of the House as Large as the Jamm of the Chimney will allow, with a two and half foot door in the Middle, & two Dressers at Each End of the Closet to reach as far as the Door, and the inside Lathed and Plastered, and that a Brick oven be built wthout in some convenient Place.

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

SUPPLEMENT

GOVERNOR'S PALACE KITCHEN

BLOCK 20 BUILDING 3J

OVEN

[Illustration]

[Illustration]

GOVERNOR'S PALACE KITCHEN - FIRST FLOOR

THE OVEN

In General

No oven was provided in this kitchen (c. 1710-1720) when it was reconstructed in 1930 because archaeological evidence for its original existence therein was inconclusive. No other location could be identified by archaeology as the site of an oven.

The foundations which were excavated on the site of the kitchen did not preclude the possibility of an oven having once existed therein.

Only one documentary reference to an oven was found, the date of which was 1779 and it is an item in Humphry Harwood's ledger which simply records repairing oven for Palace.

The interpretation of the kitchen was handicapped by the absence of baking facilities and in 1954 the Administrative officers directed Research and Architecture to make a further study of baking at the Palace and offer recommendations. This study resulted in the recommendation that an oven similar to that reconstructed in the south room of Raleigh Tavern Kitchen be built; the work was accomplished in 1955.

1. Research Notes. Humphry Harwood Ledger. Sept. 17, 1779 "To 2 Bushels of lime 16/. & ½ a days labour 10/ & Repg Oven 30/. for Palace...£2:16:0."

Research

The Director of Research, Mr. E. M. Riley, reported by memorandum dated March 11, 1955 to Messrs. Campioli that the only specific reference to an oven at the Palace which has been found is the one noted above. His memorandum recites a number of references to ovens in Williamsburg from 1776 to 1788. The references give no positive indication of the design or exact location of the ovens mentioned (see Appendix No. I for transcript of RR memo)

Architectural Investigation

The Oxford English Dictionary defines an oven as a "a chamber or receptacle of brick, stonework, or iron, for baking bread and cooking food by continuous heat radiated from the walls, roof, or floor." The same defines oven-bird as "a name given to various birds which build a domed or oven-shaped nest."

A History of Everyday Things in England 1733-1851 by Marjorie Quennell, shows the following as figure 21 with this text: "The eighteenth-century baking was done in the brick oven. This came on the side of the open fire, so that the smoke from the oven when it was lighted could escape up the main chimney."

"The oven itself was circular in plan, and domed over in brick. A bundle of faggots was put inside the oven and lighted with hot ashes. When these had burned themselves out the hot ashes were raked on one side, and into the oven went the bread and all the pies and cakes, and the entrance was closed by an iron door and, as there was no chimney from the oven, or escape for the imprisoned heat, except through this doorway, the cooking was done.

COLONIAL INTERIORS, SECOND SERIES

COLONIAL INTERIORS, SECOND SERIES

PLATE 112

Original kitchen-1725

FIG. 91.-EXTERIOR VIEW.

FIG. 92. INTERIOR VIEW.

THE BRICK OVEN, SURREY

2

It was really exactly the same principle as the cooking hole outside huts in the New Stone Age, where, after the figure had burnt itself out, the food was cooked by turves heaped over the hole."

Old English Household Life, by Gertrude Jekyll illustrates an oven by figures 91 and 92 described as follows: "Here also was the brick oven for baking bread; it showed on the outside as a semi-circular projection with a rounded top and had its own little roof. The inside was all brick; the floor flat, the sides upright for a few courses, and then arched barrel-shape. A faggot of dry brushwood went in, was lighted and by the time it was all burnt and the ashes raked out it would be the right heat for baking. Inside the back kitchen the top of the oven was stopped back in brickwork, corresponding with the rounded back outside. The mouth of the oven showed as a flat arch with a door of sheet iron with two handles that moved right out."

In the Memorandum of Several Faults in The Building of William and Mary1. in 1704 there is recorded, "...The ovens were made within the kitchen but when they were heated the smoke was so offensive that it was found necessary to pull them down and build others out of doors..."

The original brick kitchen at Tuckahoe circa 1725 has an oven on the left side of the large fireplace with no flue to the chimney and the original kitchen at Westover circa 1726 has a similar oven on the right2.

An investigation of the original brickwork in the Carter-Saunders brick quarter (c. 1751) indicated two ovens, one on either side of the large fireplace, one of which seemed to have a flue connection to the main chimney.

The reconstructed old kitchen at the St. George Tucker house (c. 1788) was equipped with an oven without a flue similar to the one at Tuckahoe because the owner, Mr. George Coleman, recalled such an arrangement having previously existed and the archaeological evidence confirmed his memory.

Oven Designs

The Palace Kitchen oven is located to the left of the fireplace and is domed, not unlike half a walnut shell in shape. It has an iron door at its only opening which is on the fireplace face. Like those at Tuckahoe and Westover it has not flue, smoke must be drawn up the fireplace chimney (which exerts a tremendous draft) or must seep out through the doors and windows.

This type of oven should be used as described above, i.e., by burning therein a wood fire until the desired temperature has been reached, then removing the ashes. The smoke must find its way up the main chimney or out through doors, windows and cracks as best it can.

COLONIAL INTERIORS SECOND SERIES

COLONIAL INTERIORS SECOND SERIES

The location on the left site of the fireplace was determined by the original foundations which place the fireplace off center of the room and leave a proper amount of space for an oven to the left.

The oven door was placed in the fireplace breast facing into the room following the precedent of Tuckahoe and Westover which are of about the same date.

The question of smoke abatement and disposition was considered and it was thought that in the 18th century designers had not yet considered the comfort of the cooks sufficiently important to provide positive means for removing the smoke. This belief is substantiated by the research notes cited above and the fact that while many oven doors open into fireplaces in the northern colonies none have been found in Virginia.

The following from Cottage Economy, by William Cobbett, London 1828 is quoted as of interest:

"104. In the mean while the oven is to be heated; and this is much more than half the art of the operation. When an oven is properly heated, can be known only by actual observation. Women who understand the matter, know when the heat is right the moment they put their faces within a yard of the oven- mouth; and once or twice observing is enough for any person of common capacity. But this much may be said in the way of rule: that the fuel (I am supposing a brick oven) should be dry (not rotten) wood, and not mere brush-wood, but rather fagot-sticks. If larger wood, it ought to be split up into sticks not more than two, or two and a half inches through. Brush-wood that is strong, not green and not too old, if it be hard in its nature and has some sticks in it, may do. The woody parts of furze, or ling, will heat an oven very well. But, the thing is, to have a lively and yet somewhat strong fire; so that the oven may be heated in about 15 minutes, and retain its heat sufficiently long.

"105. The oven should be hot by the time that the dough, as mentioned in paragraph 103, has remained in the lump about 20 minutes. When both are ready, take out the fire, and wipe the oven out clean, and, at nearly about the same moment, take the dough out upon the lid of the batting trough, or some proper place, cut it up into pieces, and make it into loaves, kneading it again into these separate parcels; and, as you go on, shaking a little flour over your board, to prevent the dough from adhering to it. The loaves should be put into the oven as quickly as possible after they are formed; when in, the oven-lid, or door, should be fastened up very closely; and, if all be properly managed, loaves of about the size of quartern loaves, will be sufficiently baked in about two hours. But they usually take down the lid, and look at the bread, in order to see how it is going on.

"106. And, what is there, worthy of the name of plague, or trouble, in all this? Here is no dirt, no filth, no rubbish, no litter, no slop. And, pray, 4. what can be pleasanter to behold? Talk, indeed, of your pantomimes and gaudy shows; your processions and installations and coronations: Give me, for a beautiful sight, a neat and smart woman, heating her oven and setting in her bread! And, if the bustle does make the sign of labour glisten on her brow, where is the man that would not kiss that off, rather than lick the plaster from the cheek of a duchess?"

Footnotes

To: Mr. Alexander

Mr. Campioli

From: E. M. Riley

Re: Governor's Palace - Brick Oven

COPY

Although Dutch ovens were listed in the inventories of several Governors who occupied the Palace, there must have been a brick oven in the kitchen to meet the culinary demands the entertaining at the Palace would have necessitated. The first and only reference, however, we have found to an oven at the Palace appears in the ledger of Humphrey Harwood a local brick mason and builder, who charged the Commonwealth of Virginia for its repair in 1779: (September 17, 1779): "To 2 Bushels of lime 16/. & one half days labour 10/. & Repg Oven 30/. for palace----2: 16: 0".

The Palace outbuildings were in ruinous condition and repaired a number of times before they disappeared. Then the main building burned the Palace was being used as a Continental hospital. In 1782 its bricks were ordered sold, and Governor Harrison suggested that the rest of the property be sold as the outhouses were "going fast to destruction" and would "be soon in ruins." By 1786 Edmund Randolph had purchased the property and repaired the flanking buildings and some of the outbuildings. His account with Humphrey Harwood mentions repairs to the "Old Kitchen," but does not make specific mention of the oven: (June 30, 1788) "to 37 days work @ 6/. & 13 days @ 4/6. Repairing Wall s to Old Kitchen-14:0:6".

(July 15) "To takeing Down Kitchen Chimney & Cleaning the Bricks 36/.---1: 16:-"

(July 21) "To Rebuilding Kitchen Chimney & Repairing End wall 60/ 3: 0:-" (Harwood Ledger B. fol. 99.)

The evidence that ovens were common in Williamsburg kitchens, is given in the Harwood Ledgers, where items for building new ovens or repairing old ones appear in many of the accounts. A few examples are cited below:

(Account with William Hunter, printer, who owned the building on lot 47 (now Pitt-Dixon House_; and built a house for his mother at the back of the Printing Office lot #48 in 1777.)27f(Ibid. B, fol 2)

1776, October 23. "To Whitewashing Chamber & parlow... To Mendg Oven & Ash House 2/ ...." 1777, March 17. "To 100 bushels of lime @ 9d. 10000 bricks @ 27/6. 21 days labr @ 2/ & 5 lods Sand a 2/ - - - (£)20; 2:0 22. To building kitching Chimney & Oven 65/ & build Do to Dwelg House 80/- - - - -- 7:5: -"

(Account with Dr. William Pasteur for work at "Farm" which must have been somewhere rear Williamsburg.)(Ibid. B- fol. 4.)

1778. March 2. "To 200 bricks 3/ 12 bushes of lime a 1/6 (4th) to 500 Do 25/ Carting them to Farm 40/ - - - 4:13- To working on 2 door frames to Kitchg 12/. & building up Old Oven 12/- - - 1: 4: - To mendg Kitching Chimney 6/. & 2 days labour 6/ - - :12: - 29 To Repairing well 10/ & 12 days Work of Old George a 2/6- - - 2: 0: - To 500 bricks 27/6 & Carting them to Farm & Building Oven 24/----- 2:11:6"

(Account with Commonwealth of Virginia during Revolutionary War)(Ibid. B, fol. 7.)

1778, July 17. "To 3900 Do (Bricks) for building Oven, at Vineyard Hospital a 100/ - - 19:10: -"

(Account with Alexander Purdie, printer - possibly for new kitchen to his dwellinghouse on lot 24 - which he occupied from ca. 1767 until his death in 1779; or possibly to the lot on which he conducted his printing business - Lot 20.)(Ibid. B- fol. 8.)

April 30, 1777. "To taking Down Kitching Chimney & Cleaning Bricks 26/----; :6:- To 80 bushels of lime @ 9d 2000 bricks a 27/6 & Cartg 6 loads of Sand 13/- - 6:7: - 28 To 1750 bricks a 27/6 20 bushels of lime @ 9d & 13 days labr a 2/-- 4: 9:12 30 To 1250 Do a 27/6 20 bushs of lime 5/ 13 days labour a 2/ & 2 Loads Sand 4/ 4:0: 4-½ To building Kitching Chumney 75/ - - - 3:5;- May 3 To 750 bricks 20/7-1/2 20 bushs of lime 15/ 15 days labr 30/ & 2 loads Sand 4/- - 3: 9: 7-½ To building Oven 15/ and laying kitching floor 30?- - - - - 2:15: - 14 To 64 bushs of lime a 9d 600 larths 7/6 6 days labr a 2/ & 2 do Sand 4/ - - 3:11: 6 To larthing & Plasterg in kitching 40/ . . . "

(Account with Lewis Burwell of Kings Mill)

1779, October 29. "To 1-½ days work of Jack Repairing Oven a 12/6 :18: -"

(Account with Benjamin Waller of Williamsburg.)(Ibid. B, fol. 10)

1780, October 4: "To Repairing Oven &: plastering do 5/ : 5: -"

(Account with Mrs. Jane Vobe who ran the King's Arms)27g(Ibid. B- fol. 11)

1779, March 20 "To 31 bushs of lime a 4/6 & 1950 bricks a 16/6 & 7 Days Labour a 12/. 19:16 :9 To Building an Oven 150/ Repairg Stove 12/ & Do to underping Shop 6/ 7:16: -"

(Account with John Carter, merchant, who occupied a house on the site of the present James City County-Williamsburg Court House, and also had a store adjoining the Raleigh to the west) Ibid., fol. 12.

May 7, 1778: "To Mending Kitching Chimney 12/. & laying harth 5/. & Cartg @ load of Sand 4/ 1:l:0" May 13, 1778: "To Altering Spout to Spring 6/. & laying Kitchg floor 10/. & Do Oven harth 4/. 1:0:-".

(Account with Cornelius DeForrest, who in 1776 advertised himself as "baker near the CAPITOL", and who at end of his account Harwood noted as "insolvent" (See Ibid, B, fol. 15)

1776 April 13. "To 4800 Bricks @ 27/6 & 80 bushels of lime @ ...9d £9:12:0 ...18 "To 400 bricks 11/ & Building A Oven 35/ - 2: 6: 0" 1778 August 8 "To 22100 bricks @ 192/ pr M & 270 bushs of lime @ 5/95/9 288:16:6 To 36 Days labr a 15/ & Carting 16 loads of Sand a 16/ 39:0: ) To 7 Days work Rubing Bricks for Oven Harthes a 42/ & 1 bus of hair @ (--illeg.) 15:2:9 To Building A pair of Ovens, & Chminey £96.12.0 96.12.0 October 16th to 1700 bricks @ 2716 pr M (Old price) 2: 6: 9 (involvevent)"

As can be seen from these references taken from the first fifteen folio pages of the Harwood ledger, there is a wealth of information in this leger on the subject of ovens. Unfortunately, a careful study of the ledger has not revealed any additional information on the Palace oven. It is logical to assume that the oven was placed inside the kitchen building; and that it was not the large size used by commercial bakers. In other words, the oven should not be so large as to dominate the remainder of the kitchen. It should be clear to the visitors that the building was used as a kitchen and not a bakery.

E.M.R.

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

GOVERNOR'S PALACE KITCHEN

- AMPTHILL, Chesterfield County

-

- Windows of

- 15

- Antique Warehouse

- BARGE board

- Baseboard

- Beams of second floor

-

- Type used

- 24

- Botetourt, Lord

- Brick

- Brickwork of Kitchen

- Bright, Mr.

-

- Family of, once lived in West Flanking building

- 2

- Brush-Everard House

-

- Chimney of kitchen of

- 12

- CABOT'S Double White

-

- Used for exterior woodwork

- 5

- Carter's Grove

- Chamber

- 25, 26

- Chimney of Kitchen

- Colors used on Kitchen

- Cook's Bed Chamber

- 24, 25

- Cornice end board (or stop)

-

- Precedent for

- 14

- Cornice of Kitchen

- DENT, Lucien

-

- Made working drawings

- Title page

- Doors

- Dormer windows of Kitchen

- EAST Flanking Building of Governor's Palace

-

- Vault found under

- 2

- Electrical system in Kitchen

-

- Outlets of

- 17

- Elevations of Kitchen

- Exterior of Kitchen

- 6-15

- FENESTRATION of Kitchen

-

- Relation of area of to the floor space

- 4

- Fireplaces

- First floor of Kitchen

- 17-23

- 29.

- Floor

- Foundations, old

- Foundations, new

- GENERAL Notes on Kitchen

- 1-5

- Greenhow Repiton Brick Office

-

- Chimney cap of

- 12

- Guard House of Governor's Palace

-

- Shown on photograph

- Frontispiece

- Gutter and leader of Kitchen

- 9, 15

- HARWOOD, Humphrey

- Heart yellow pine

- Heating system of Kitchen

- Hexagonal Building

-

- Shown on photograph

- Frontispiece

- Household utensils

- INTERIOR of Kitchen

- 16-27

- KING'S Mill

- Kiskiak, York County

- Kitchen of Governor's Palace

-

- Reconstruction of

-

- Started, January, 1933

- Title page

- Completed August, 1933

- Title page

- Research report on

- Title page, 1

- Archaeological investigations of

- Title page

- Location of, discussed

- 1-3

- Mentioned in Botetourt inventory

- 3

- Method of determining size of

- 3

- Foundations of, discussed

- 3-7

- Exterior of

- 6-15

- Interior of

- 16-27

- Plans of, reproduced

- 16a

- Heating system of

- 16, 17, 22

- Kitchen Service Court

-

- Old Foundations about

- 4

- Kitchens in colonial Virginia

-

- Report on

- 16

- LADDER

- Laundry of Governor's Palace

-

- Shown on photograph

- Frontispiece

- Leader,

- see "Gutter and leader"

- MACOMBER, Walter

-

- In charge of Williamsburg office

- Title page

- Marlfield, Gloucester County

- Marmion, King George County

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

- Authorities at, authenticated colors

- 5

- Moorehead, Singleton P.

-

- Job captain and draftsman for Kitchen

- Title Page

- Author of this report

- Title page

- Author report on Palace Stables

- 2

- Mortar of brickwork

-

- Characteristics of

- 6

- NAILS, Floor

-

- Type used

- 24

- OFFICES

- Outbuildings southwest of Palace

-

- Photograph of, taken from Palace roof

- Frontispiece

- "Outbuildings Belonging to Kitchen"

- 30.

- Ovens in Eighteenth-century fireplaces

- PARADISE House

-

- Door trim of

- 21

- Perry, Shaw and Hepburn

-

- Architects for reconstruction of Kitchen

- Title page

- Letter by H. D. Shurtleff to

- 2

- Plans of Kitchen, reproduced

- 16a

- Plastering of Kitchen walls

-

- Description of method

- 18

- Pine,

- see "Heart yellow pine"

- Precedent

-

- Followed in reconstruction of exposed parts

- 5

- Putlock holes

-

- Meaning of, explained

- 13

- RAGLAND, Herbert

-

- Conducted archaeological investigations

- Title page

- Archaeological report of

- 7

- Rake board,

- see "Barge board"

- Randolph, Edmund

- Research report on Kitchen

-

- Compiled by Harold R. Shurtleff

- Title page

- Richie House, Tappahannock

-

- Chimney of

- 12

- Roof of Kitchen

-

- Manner of laying of

- 8

- SALT House

-

- Shown on photograph

- Frontispiece

- Foundations of, identified

- 4

- Saluda

-

- Brick house between this and West Point

- 7

- Sash

- Scullery of Governor's Palace

-

- Shown on photograph

- Frontispiece

- Scuttle in chamber

-

- Precedent for

- 26

- Second Floor

- 24-27

- Servant's Hall of Kitchen

- 22, 23

- Shingles

- Shurtleff, Harold R.

-

- Compiled research report

- Title page

- Letter of, to Perry, Shaw and Hepburn

- 2

- Smith Place, Suffolk

- Smoke House

-

- Shown on photograph

- Frontispiece

- Foundations of, discovered

- 1, 2

- Foundations of, identified

- 4

- Stable of Governor's Palace

- Step, entrance

-

- Description of

- 9

- Stratford

- Stratton Major Parish

- TIDEWATER Virginia

-

- Brick Kitchens of

- 3

- Townshend, J.M.

-

- Made working drawings

- Title page

- Trim, exterior

- Tuckahoe, Goochland County

-

- Cornice stop of

- 15

- Tucker, St. George, House

-

- Ladder of

- 26

- UTENSILS,

- see "Household utensils"

- VAULT

-

- Found beneath East Flanking Building

- 2

- WALKER, Richard A.

-

- Made working drawings

- Title page

- Wall, exterior

- Wall, interior

-

- Description of

- 18

- Warburton House

-

- Dormers of

- 7

- Watertable of Kitchen

-

- Characteristics of

- 12

- Well, West

-

- Shown on Photograph

- Frontispiece

- West Flanking Building of Governor's Palace

- West Point

-

- Brick house between this and Saluda

- 7

- Westover

- Williamsburg Holding Corporation

-

- Palace Kitchen reconstructed by

- Title page

- Windows of Kitchen

- Working drawings for Kitchen

- Title page

- YELLOW Pine,

- see "Heart yellow pine"

INDEX