Brush-Everard Kitchen Architectural Report, Block 29 Building 9 Lot 165 Originally entitled: "The Original Brush-Everard Kitchen Block 29, Building 9, Colonial Lot 165"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1571

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

THE BRUSH-EVERARD KITCHEN

ORIGINAL BLOCK 29, BUILDING 9 COLONIAL LOT 165

SUMMARY ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

ARCHITECTS' OFFICE

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG

PREFACE

The Architects' Office has compiled architectural reports for most of the buildings restored or reconstructed by Colonial Williamsburg. These reports, together with the drawings and specifications, provide a permanent record of each building's architectural development. Reports on the houses usually include information about the outbuildings belonging with them. The Brush-Everard kitchen, however, requires individual consideration. It is the only eighteenth-century brick kitchen surviving in Williamsburg. The clay floor, recently restored to its interior, is furthermore the sole example of its kind recreated here. Because the Brush-Everard House Architectural Report contains few explicit facts concerning the kitchen and because the kitchen's recent opening as an exhibition building may elicit questions of an architectural nature, the following report has been prepared as a reference source. It is not intended to be a detailed analysis, but summarizes, rather, important aspects of the kitchen's architectural character. An introductory historical synopsis is given to supply background material and to clarify statements in the report referring to the history of colonial lots 165 and 166. The accompanying photographs and drawings, besides illustrating the text, offer implicit description of features not discussed in the report.

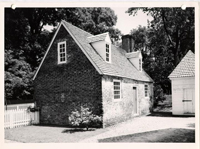

ILLUSTRATION # 1. THE BRUSH-EVERARD KITCHEN: WEST AND NORTH ELEVATIONS

ILLUSTRATION # 1. THE BRUSH-EVERARD KITCHEN: WEST AND NORTH ELEVATIONS

SUMMARY OF THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE HISTORY

The trustees of Williamsburg sold lots 165 and 166 to John Brush, a gunsmith, on July 8, 1717. There were no houses on the property, for the deed contained the usual building clause. (Building regulations for the city of Williamsburg were enacted by the General Assembly in 1699 and revised in 1705.(1)) Brush constructed at least two major building by 1719; otherwise, the land would have reverted to the city. He died in November or December of 1726, bequeathing his "houses and lots" to his spinster daughter, Elizabeth, and his son-in-law, Thomas Barber, a carpenter. Within three months, Elizabeth Brush conveyed her share to Thomas Barber. Barber himself died three months later (May, 1727), having willed the property to his wife, Susanna Brush Barber. Elizabeth Russell, widow, bought it from Susanna Barber in 1728. Evidently Elizabeth Russell married Henry Cary II, a master-builder, for in 1742 Cary and his wife, Elizabeth, deeded the lots to William Dering, a dancing master. Dering mortgaged the property several times; it was finally auctioned to an unknown purchaser in February, 1751. The ownership of lots 165 and 166 is uncertain between 1751 and 1779. Records suggest that either John Blair or Thomas Everard purchased the property at the "outcry" in 1751. Everard, clerk of York County, was definitely owner in 1779 and he may have obtained it as early as 1751-1753. John Stith 1782-87His acquisition of lot 172 in September, 1773 indicates that he already held the other two lots. Everard died in 1781. His son-in-law, Dr. Isaac Hall of Petersburg, was taxed for the three lots in 1788, the same year that he sold them to Dr. James Carter. Hall rented the property during his possession. The occupant from 1781 to 1785 was Mrs. Susanna Riddle, widow of Dr. George Riddle of Yorktown. Carter or his estate retained the property until 1820, when it was devised to Milner Peters of Norfolk, heir through his wife's rights. Dabney Browne, professor at the College of William and Mary, bought it in 1830 and sold to Daniel P. Custis fifteen years later. Sydney Smith became the next owner in 1849. He died in 1881, leaving the property to his seven children. The Smith family transferred the deed in 1928 to Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin, who represented the Williamsburg Holding Corporation. Miss Cora and Miss Estelle Smith, daughters of Sydney Smith, retained life tenure rights. Miss Estelle Smith, the survivor, died in 1946.(2)

Colonial Williamsburg restored the Brush-Everard property between May, 1949 and January, 1952. Since then it has been open to the public. The Brush-Everard group consists of three original buildings (the dwelling, kitchen and smokehouse) and seven reconstructed outbuildings.

Completion date: May 1951

Opening date: Jan. 22, 1952

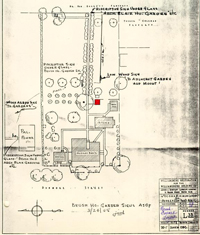

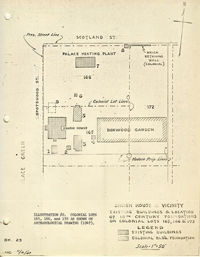

ILLUSTRATION #2. COLONIAL LOTS 165, 166, and 172 AS SHOWN ON ARCHAEOLOGICAL DRAWING (1947).

ILLUSTRATION #2. COLONIAL LOTS 165, 166, and 172 AS SHOWN ON ARCHAEOLOGICAL DRAWING (1947).

SKETCH SHOWING ELEVATIONS OF BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE PROPERTY (Block 29, Building 10) TAKEN FROM ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY. James M. Knight & H. H. C. March 26, 1949.

SKETCH SHOWING ELEVATIONS OF BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE PROPERTY (Block 29, Building 10) TAKEN FROM ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY. James M. Knight & H. H. C. March 26, 1949.

NOTE: Pre-restoration location of the Smokehouse (Block 29, Building 15), east of the original Kitchen (Block 29, Building 9), before being returned to its original site southwest of the Kitchen.

THE BRUSH-EVERARD KITCHEN

The Brush-Everard kitchen is one of twenty-eight eighteenth-century outbuildings in Williamsburg. It is the only extant brick kitchen.(3) Initially constructed as a small frame building (ca. 1730-1750), it was altered twice before the end of the eighteenth century. The kitchen has been restored to its third form, preserving its late characteristics as a one-story, two-room brick structure.

Colonial Williamsburg restored the kitchen in two stages. Exterior restoration was completed in 1952. The first floor interior was restored in the spring of 1968. (4) Archaeological excavations of the site were conducted during 1946-1947 and February, 1967. For sixteen years the kitchen, in its partially restored state, was open to the public as an architectural exhibit. The unfinished interior offered an excellent display of eighteenth-century building techniques, of structural developments typical in an original building, and of preliminary conditions encountered by restoration architects. During the recent expansion of Colonial Williamsburg's presentation program, it was decided to reinstate an authentic eighteenth-century interior appearance. The kitchen was opened for exhibition on July 1, 1968.

The exact age of the Brush-Everard kitchen and the dates of its alterations are unknown. Scant documentary evidence of its existence has been found and even the available records are inconclusive. Surviving legal documents, beginning with John Brush's will (dated November 26, 1726), cite collectively the "houses," "buildings," "outbuildings," and "outhouses" standing on the property. The Frenchman's Map (ca. 1782) shows a dwelling and five northwest outbuildings on lots 165 and 166.

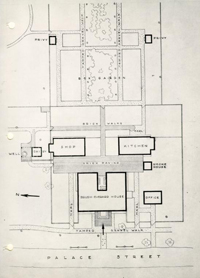

ILLUSTRATION #3. COLONIAL LOTS 165 and 166 AS SHOWN ON THE FRENCHMAN'S MAP (1782) AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL DRAWING (1947).

2.

Presumably the southernmost outbuilding represents the kitchen. The earliest specific reference to the kitchen appears in an account book kept by Humphrey Harwood, local bricklayer and carpenter. Harwood did work for Mrs. Susanna Riddell in 1783 and 1784, itemizing in his ledger repairs to the house and five outbuildings. Included among his entries were charges for laying brick paths to the kitchen, laying the kitchen hearth, and patching the building's interior and fireplace plastering.

ILLUSTRATION #3. COLONIAL LOTS 165 and 166 AS SHOWN ON THE FRENCHMAN'S MAP (1782) AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL DRAWING (1947).

2.

Presumably the southernmost outbuilding represents the kitchen. The earliest specific reference to the kitchen appears in an account book kept by Humphrey Harwood, local bricklayer and carpenter. Harwood did work for Mrs. Susanna Riddell in 1783 and 1784, itemizing in his ledger repairs to the house and five outbuildings. Included among his entries were charges for laying brick paths to the kitchen, laying the kitchen hearth, and patching the building's interior and fireplace plastering.

Although the kitchen cannot be precisely dated by historical methods, the periods of its development have been determined through archaeological and architectural research.(5) The building evolved in three stages. It was originally constructed after ca. 1730. Recent archaeological findings conclusively established that no part of the present kitchen existed during John Brush's ownership. Its first alteration occurred ca. 1740-1760. The first and second period structures originated, then, while Elizabeth Russell, Henry Cary II, or William Dering held the property. The kitchen was enlarged "no earlier than the mid-eighteenth century, but possibly as late as circa 1790."(6) Thomas Everard probably built the north extension. Artifacts excavated in the kitchen vicinity confirm his presence on lots 165 and 166 as early as 1756. Historical records intimate that he was living there by 1751 and verify his occupancy from 1779-1781, so the period of the kitchen's final enlargement falls within the plausible limits of Everard's ownership. The north addition was the last major alteration to the kitchen though several architectural changes were made during the nineteenth century.

3.The first kitchen was a one-story, one-room, frame structure. Brick foundation walls, 9"-thick and laid in English bond, supported the building. Its exterior measurement, approximately 17' x 20', was a typical eighteenth-century kitchen size. Three sides of the building were faced with weatherboards, but the south (chimney) end was entirely brick. The latter feature was a colonial safety measure; a masonry chimney wall reduced fire hazard by providing a buffer between wood structural members and heated brickwork near the fireplace. The kitchen's large chimney held a fireplace about 6 feet wide by 3½ feet deep and had a brick bake oven against its east face. The chimney, with an average wall thickness of eighteen inches, was laid in English bond below grade and in Flemish bond above grade. It may be reasonably assumed that the door and window placements in the wood kitchen's front and rear walls were repeated in the subsequent brick version of the building; if so, the first kitchen had a window and (northwest) entrance door on the west side and two east windows. An A-roof, without dormers, covered the building. The interior walls, ceiling, and fireplace were plastered. Artifacts discovered during the 1967 archaeological excavation suggest that delft tiles may have decorated the interior. The floor inside was yellow clay.

Around 1750 the kitchen was converted to a brick building with one frame end (the north wall). Its basic plan and exterior dimensions remained unchanged, since the alteration involved little more than replacement of the front and back walls. The entire east wall, including its foundation, was supplanted with a brick wall uniformly 13"-thick from footing to roof line. (The east end of the north foundation was cut off in the process of laying the Period II east wall, but this apparently

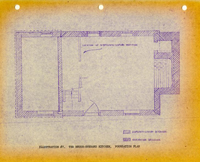

ILLUSTRATION #4: THE BRUSH-EVERARD KITCHEN: PLANS AND ELEVATION SHOWING ARCHITECTURAL DEVELOPMENT (Note: The eighteenth century partition is incorrectly located on plans for Periods III, IV, and V. See: Illustration #7)

4.

did not affect the width of the building.) The 13" brick wall raised on the west side was for some reason laid on the earlier 9"-thick foundation, resulting in a 4" exterior overhang at the transition point between the old and new brickwork. All second period brickwork was laid in English bond and was devoid of ornamentation (i.e., no rubbed or glazed bricks were used). As noted above, the second kitchen had a door and one window on the west side and two east windows. These front and rear openings were not centered opposite each other and the east windows were made taller and narrower than the west window.

ILLUSTRATION #4: THE BRUSH-EVERARD KITCHEN: PLANS AND ELEVATION SHOWING ARCHITECTURAL DEVELOPMENT (Note: The eighteenth century partition is incorrectly located on plans for Periods III, IV, and V. See: Illustration #7)

4.

did not affect the width of the building.) The 13" brick wall raised on the west side was for some reason laid on the earlier 9"-thick foundation, resulting in a 4" exterior overhang at the transition point between the old and new brickwork. All second period brickwork was laid in English bond and was devoid of ornamentation (i.e., no rubbed or glazed bricks were used). As noted above, the second kitchen had a door and one window on the west side and two east windows. These front and rear openings were not centered opposite each other and the east windows were made taller and narrower than the west window.

A brick extension, added in the last half of the eighteenth century, enlarged the kitchen to its present size (29'-1" x 16'-11"). The addition was built on the north side of the second kitchen and, in contrast to the earlier brickwork, its walls were laid in Flemish bond on substantial spread footings. A scattering of glazed headers variegated the brickwork.(7) A vertical joint in both the east and west walls clearly separated the two periods of brickwork and defined the exterior limits of the north addition. The new part merely lengthened the kitchen; the building's width was constant throughout its history. The north frame wall was retained in the third kitchen as an interior partition. Two windows, matching the disparate first floor windows in the older section, were put in the front and back walls of the north addition; the west window had sixteen lights and the rear window had eight panes. An eight-light window was inserted in the north gable and two dormers were framed into the front roof slope. The addition of three windows to the unlighted attic space constituted a considerable improvement. It was probably done to increase the livability of the area, since the upper floor in many outbuildings was used for housing servants and 5. slaves. This was apparently the case at the Brush-Everard kitchen, for the early chimney was large enough to accommodate a fireplace in the attic.(8) The existing steep stair was constructed against the south side of the newly established interior cross wall during this phase of remodeling. Until then, a ladder probably sufficed for access to the attic. That the third kitchen's interior walls and fireplace were plastered is substantiated by Humphrey Harwood's ledger. In the eighteenth century it was customary to whitewash plastering. A brick floor was laid in the new north room, but the south room's clay floor was undisturbed. (The clay floor remained, in fact, until ca. 1825.)

Incidental alterations, generally in the form of repairs, were made to the kitchen throughout the next century and a half. The condition of the original chimney declined until it was finally torn down to grade level and replaced with a smaller chimney. Along with this change, which occurred around the middle of the nineteenth century, the kitchen's south wall and adjacent portions of the east and west walls were rebuilt. An L-shaped foundation against the west side of the Period T chimney foundation attests to an earlier nineteenth-century attempt to support the crumbling chimney with a brick retaining wall. Long before the original chimney was demolished, the bake oven was dismantled and a doorway opened in its place at the southeast corner of the building. Exterior step foundations were found in that location during the 1947 excavation. Another nineteenth-century doorway was substituted for the center window on the east side of the kitchen. The east and west doorways were fitted with roughly fashioned board-and-batten doors. A

ILLUSTRATION #5. INTERIOR BEFORE RESTORATION SHOWING 19th CENTURY PARTITION VIEW TO NORTH.

6.

south gable window was added west of the chimney. In the late nineteenth century, when the roof was being re-shingled, the dormer windows were removed. Inside the building, a new frame partition was erected several feet south of the original north wall's position. It was constructed of old weatherboards and structural members. (See: Illustration #5.) After the first quarter of the nineteenth century, the original clay floor in the south room was covered with two brick floors, a layer of marl and, finally, wood. Two successive brick renewals overlaid the north room's first brick floor. The interior plastering was extensively repaired. A make-shift door was fabricated in the attic, incorporating an original paneled shutter from the Brush-Everard house.(9) (The kitchen itself never had shutters.) Most of the nineteenth and twentieth-century modifications, except those in the attic, were stripped from the kitchen when it was restored.

ILLUSTRATION #5. INTERIOR BEFORE RESTORATION SHOWING 19th CENTURY PARTITION VIEW TO NORTH.

6.

south gable window was added west of the chimney. In the late nineteenth century, when the roof was being re-shingled, the dormer windows were removed. Inside the building, a new frame partition was erected several feet south of the original north wall's position. It was constructed of old weatherboards and structural members. (See: Illustration #5.) After the first quarter of the nineteenth century, the original clay floor in the south room was covered with two brick floors, a layer of marl and, finally, wood. Two successive brick renewals overlaid the north room's first brick floor. The interior plastering was extensively repaired. A make-shift door was fabricated in the attic, incorporating an original paneled shutter from the Brush-Everard house.(9) (The kitchen itself never had shutters.) Most of the nineteenth and twentieth-century modifications, except those in the attic, were stripped from the kitchen when it was restored.

Both restoration projects entailed extensive replacement of original elements. Though the kitchen's eighteenth-century fabric was largely extant in 1949, many of its features were irreparably deteriorated. Elements which had wholly disappeared, such as the dormer windows, the west door, baseboards, and various trim members, were restored on the basis of local precedent. Otherwise, intrinsic clues to the nature and appearance of missing features still existed. Vestiges of the original frame structure, for example, were discovered within the building. Not only did the surviving 9" foundation walls indicate, by their size, the initial presence of a wood building, but also the first kitchen's northwest cornerpost was found embedded in brickwork north of the entrance door. The ceiling beam from the north frame end, its notches showing the original stud distribution, rested over the cornerpost. In addition, the foundation

ILLUSTRATION #6. THE BRUSH-EVERARD KITCHEN: EAST AND SOUTH ELEVATIONS RESTORED

ILLUSTRATION #6. THE BRUSH-EVERARD KITCHEN: EAST AND SOUTH ELEVATIONS RESTORED

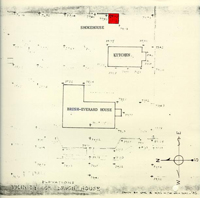

ILLUSTRATION #7: THE BRUSH-EVERARD KITCHEN, FOUNDATION PLAN

7.

for the partition was intact. These structural remnants allowed an exact restoration of the one wall that was common to the kitchen's three distinct variations.

ILLUSTRATION #7: THE BRUSH-EVERARD KITCHEN, FOUNDATION PLAN

7.

for the partition was intact. These structural remnants allowed an exact restoration of the one wall that was common to the kitchen's three distinct variations.

An outline of the kitchen's restored condition, distinguishing between old and new materials, is given below.

STRUCTURAL

FOUNDATIONS:

The original brick foundations were maintained. Weak spots were reinforced with concrete underpinnings and protective walls. The entire chimney end was underpinned with concrete. A concrete slab was poured on the interior.

BRICKWORK:

All eighteenth-century exterior brickwork was preserved. It was repaired and repointed where necessary, with most of the patching concentrated around window and door openings. New brickwork was laid in reconverting the nineteenth-century east doorway to a window. The kitchen's south wall, the south corners of the east and west walls, the chimney, and the bake oven were entirely rebuilt. Some of the handmade bricks used in the south wall and chimney were salvaged from the kitchen's nineteenth-century brickwork. Terra cotta flue linings were installed in the T-shaped chimney stack. The original interior brickwork received minimal repairs. Characteristics of the eighteenth-century brickwork are as follows: 8.

| Brick size | 9" x 4-¼" x 2-¾" |

|---|---|

| Color | Buff and light red |

| Bond | English and Flemish |

| Mortar | Shell |

| Brick size | 8-5/8" x 4-1/8" x 2-5/8" |

|---|---|

| Color | Dark red and purple |

| Bond | English |

| Mortar | Shell |

| Brick size | 8-3/8" x 3-7/8" x 2-5/8" |

|---|---|

| Color | Dark and light red; also glazed headers |

| Bond | Flemish |

| Mortar | Shell |

| Brick size | 9" x 4-3/8" x 2-5/8" |

|---|---|

| Color | Salmon |

| Bond | English |

| Mortar | Shell |

FRAMEWORK:

The kitchen's wood skeletal construction consists of framing in the roof, the attic, the dormers, the first floor ceiling, and the first floor partition. The dormers were framed with old structural pieces from the Brush-Everard house. Two original timbers the ceiling beam and west cornerpost - were reused in 9. reconstructing the north partition. The nineteenth-century frame partition and a jib wall in the attic were removed from the building. The rest of the framework is made up of old structural members which were found in place at the beginning of restoration, repaired, and reinforced with new materials. The wood throughout is yellow pine.

EXTERIOR

The following notes pertain only to the kitchen's exterior finish, as the structural components are treated above.

DOORS:

The original west doorway was reinforced with a steel lintel and fitted with a new door, frame, and sill. Yellow pine was used for the woodwork. The architrave has three members: cyma reversa (ogee) molding; fascia; and bead. The door itself is double sheathed with horizontal and vertical boards. The wrought iron door hardware includes: an antique spiral hook (existing on the west door when restoration began); an antique lock; a reproduction thumb latch; and a pair of reproduction H-and-L hinges.

WINDOWS:

The kitchen has eight windows of four different sizes. All the frames and sash are new, but the glazing throughout is antique. The window panes were salvaged from the kitchen itself and from other local sources. Only the dormer window frames have molded trim; the others were copied from single-member, beaded and pegged frames found in the kitchen's west windows. 10. The eighteenth-century sash existing in the two front windows at the onset of restoration had apparently been relocated there from a first floor window in the Brush-Everard house. Their muntin profile provided a pattern for the kitchen's new sash detail. The restored sash are double-hung and equipped with wood sash buttons. The frames and sash are made of pine.

The fenestration in the kitchen's east and west elevations is completely asymmetrical. The entrance door is slightly off-center to the south; the front and back windows are not centered opposite each other; and the dormers are not aligned directly above the first floor west windows.

Below are listed the windows, their sash arrangements, and the antique glass sizes.

| W-101 | West Elevation | 16 | 4 high x 4 wide | 6-½" x 8-½" |

| W-102 | ||||

| W-103 | East Elevation | 8 | 4 high x 2 wide | 8-½" x 9-½" |

| w-l04 | ||||

| W-105 | ||||

| W-201 | North Gable | 8 | 4 high x 2 wide | 7-¼" x 9" |

| W-202 | West Dormers | 8 | 4 high x 2 wide | 6½" x 8-½" |

| W-203 |

ROOF:

The kitchen's A-roof is pitched at an angle of 51° 20'. New hand-split, round-butt, cypress shingles, treated with a fire-retardant substance, cover the roof. The gable ends are finished with new beaded and tapered pine rake boards. A pine soffit board, instead of a cornice, trims the east and west roof eaves.

DORMERS:

The two dormers in the west roof slope were built according to framing marks in existing rafters. Their design is typical of eighteenth-century gable type dormers. The roofs have a 48° 10' pitch and are covered with round-butt cypress shingles. The cheeks are faced with random width flushboarding. The flush board tympana are framed by beaded, tapered rake boards and molded cornices trim the eaves. All the dormer woodwork is pine.

PAINT:

The exterior paint colors, selected to harmonize with the paint on the dwelling, are: ochre on the rake and soffitt boards; white on the window sash and frames, door trim, and dormers; dark green on the west door.

INTERIOR

The following notes apply to the kitchen's first floor appearance. Preservation work done in the attic was limited to measures that would stabilize its condition and make it structurally sound. Discounting structural elements, the stair is the only original feature on the first 12. floor. The interior woodwork, except where otherwise stated, is pine. Dimensions of the kitchen's two rooms are:

| South Room | 18'-6" x 14'-8" | |

| Ceiling height | 8'-3" | |

| North Room | 7'-3" x 14'-8" | |

| Ceiling height | 8'-8" |

FLOORS:

The floor level in the north room is 5" lower than that in the south room. Both rooms have a yellow clay floor.

Builder's handbooks and dictionaries published in eighteenth-century England mention clay among the common flooring materials of the period. Not only had clay floors been used there for centuries, but they appeared, moreover, in buildings as disparate as barns and churches. Clay floors were less prevalent in colonial Virginia, probably because abundant supplies of timber and brick were available here. Like dirt floors, they were usually relegated to outbuildings.

One reference source, the anonymously authored BUILDER'S DICTIONARY: OR, GENTLEMAN AND ARCHITECT'S COMPANION, printed in London in 1734, contains a

lengthy description of clay floors and their treatment. They were recommended as "hard, strong and durable" "done in a hot and dry Season". The floor had to be well tempered, leveled and mellowed, a process that took two to three weeks for completion. Admixtures suggested to strengthen the loamy clay were

ILLUSTRATION #8. SOUTH ROOM-RESTORED VIEW TO NORTH

ILLUSTRATION #8. SOUTH ROOM-RESTORED VIEW TO NORTH

ILLUSTRATION #9. SOUTH ROOM- RESTORED VIEW TO SOUTH

13.

lime, brook sand, "Gun-Dust, or Anvil-Dust from the Forge", horse dung, coal ashes, egg whites, or ox blood. When made with lime and egg whites, the finished floor could be polished with oil to the brilliance of glass or metal. Sir Hugh Platt's recipe, combining ox blood and fine clay, was recommended for making "smooth, glittering" floors and "for plastering of Walls". His method supposedly produced "the finest Floor in the World."(10)

ILLUSTRATION #9. SOUTH ROOM- RESTORED VIEW TO SOUTH

13.

lime, brook sand, "Gun-Dust, or Anvil-Dust from the Forge", horse dung, coal ashes, egg whites, or ox blood. When made with lime and egg whites, the finished floor could be polished with oil to the brilliance of glass or metal. Sir Hugh Platt's recipe, combining ox blood and fine clay, was recommended for making "smooth, glittering" floors and "for plastering of Walls". His method supposedly produced "the finest Floor in the World."(10)

Colonial Williamsburg, in reproducing the Brush-Everard kitchen floor, used a pure quality, mixed yellow clay. It was compacted, smoothed and cured, treated with a modern preservative and, when dry, finished with a clear sealer. An adaptation of original methods was necessary to protect the floor, since the anticipated wear of visitor traffic would far exceed the effect of a few bare or lightly shod eighteenth-century feet.

BASEBOARDS:

Ogee molded baseboards trim the outer walls of each room. Beneath the north partition, however, the foundation bricks and wood plate are exposed.

WALLS AND CEILINGS:

Gunite (sprayed concrete), finished to simulate plaster, was applied over the interior brick walls, the west door sill, and the heads, jambs and sills of windows in the south room. The ceilings and south side of the partition were covered with metal lath and plaster rather than gunite. These areas 14. have rough surfaces simulating the texture of oyster shell plaster. Beaded weatherboards face the north side of the frame partition.

DOORS:

West Door: The west door's inner architrave is a beaded board. As noted above, the sill is simply gunite. For further description, see notes under "Exterior".

North Door: Architraves on either side of the north doorway are identical to the west door's interior trim. The sill is an oak plank. The board-and-batten door has wrought iron, reproduction hardware: a pair of H-and-L hinges and a rat tail latch.

WINDOWS:

The two windows in the north room have wood jambs and sills. The south room's plaster window treatment is noted above. The window locks are reproduction, wrought iron pintles attached to leather straps. Other window details are included under "Exterior".

FIREPLACE AND BAKE OVEN:

The south room's clay floor extends to the edge of the arched fireplace opening, precluding a hearth. Except for the brick underfire, the inside of the fireplace is plastered. Brickwork within the bake oven is exposed. The wrought iron oven door is a reproduction.

15.STAIR:

The stair in the south room is hardly more than a substantial ladder, for it consists only of stringers and treads. The string boards (repaired) and three treads are original; all the nosings are new. The tongues of two treads protrude and are wedged on the outer stringer face. Beaded boards enframe the stair well.

PAINT:

The walls, ceiling, fireplace, and woodwork (except the stair treads and north door sill) are painted with simulated whitewash.

FOOTNOTES

See also: Richard Neve, THE CITY AND COUNTRY PURCHASER'S AND BUILDER'S DICTIONARY (London: Printed for B. Sprint, et al., 1736); M. W. Barley, THE ENGLISH FARM-HOUSE AND COTTAGE (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1961); C. F. Innocent, THE DEVELOPMENT OF ENGLISH BUILDING CONSTRUCTION (Cambridge: The University Press, 1916), pp. 157-161; A. Lawrence Kocher, Floors, Floor Cloth, Carpets in 17th - 18th Century Architectural Meaning and Usage, Special Study, Architects' Office, Colonial Williamsburg, December 21, 1945, pp. 19-23.

To: Mr. W.E. Jacobs

From: Paul Buchanan

Re: Brush-Everard Kitchen

Block 29, Building 10-B

Project #66-017

This is to authorize you to remove and destroy the nineteenth-century wood partition which is now loose on the first floor of the above-noted building.

Please retain the piece of window trim at the head of the northeast window on the first floor and widen the piece on the side next to the window frame. These matters were discussed by Mr. Hardy and Mr. Bob Taylor.

P.B.

Copy to:

Mr. Taylor

PB:[illegible]

Pertains to Drwg 205 Brush Kitchen filed, J IC

ILLUSTRATION #11

ILLUSTRATION #11

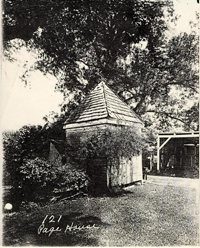

"THE AUDREY HOUSE, WILLIAMSBURG, VA. POST CARD (ca. 1905) THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE (Block 29, Building 10) Original loaned by Page W. Laubach, Williamsburg, Va.

Brush-Everard Kitchen (Pre-restoration) Block 29, Building 9

Brush-Everard Kitchen (Pre-restoration) Block 29, Building 9

Layton Negative #L-122

Album: "Pre-Restoration #2"

Brush Everard House (pre-restoration) Block 29, Building #10

Brush Everard House (pre-restoration) Block 29, Building #10

East Elevation

Negative #(B-29 (?) [Block 29]) also marked on front "A No. 3"

Album: "Pre-Restoration #2"

Brush-Everard Smokehouse, Block 29, Building 15 (pre-Restoration)

Brush-Everard Smokehouse, Block 29, Building 15 (pre-Restoration)

Negative #L-121 (Layton)

Album: "Pre-restoration #2"