Robert Carter House Architectural Report, Block 30-2 Building 13 Lot 333-336Originally entitled: "Carter-Saunders House (Restored) Block 30, Col. Lots 333, 334, 335, 336"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1611

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

CARTER-SAUNDERS HOUSE, Block 30, Lots 333, 334, 335, 336.. OUTBUILDINGS AND GROUNDS

DATE -

DATE OF RESTORATION -

Summary of Carter-Saunders House History

- I.GENERAL

- 1.Name (names) of property.

- 2.Location of property: Block No., Colonial Lot Nos. Extent and location of these Colonial lots in relation to present-day streets and property divisions.

- 3.General description of existing property, listing and describing briefly house, outbuildings,

and landscape features.and arrangement of property. Partly L. S. Foster house and lot.-etc.

- II. HISTORICAL

- 1.Outline of outstanding facts concerning successive occupants and occupancy of property (summary of material from Research Report and any other available sources, including maps, such as the Unknown Draftsman's, the Galt, the Tyler, the Bucktrout, the Bucktrout-Lively, and the Frenchman's Maps.).

- 2.Isolation and analysis of any facts in above data which throw. light upon:

- a)the original condition of house, outbuildings and grounds

- b)subsequent changes in the above, including extension of Saunders property to embrace Deane lots.

- III. ARCHAEOLOGICAL

- 1.Description of foundation walls, paving, etc. found by excavation on property.

- a)Analysis of the successive building periods represented by the walls uncovered.

- b)Clarification, as far as possible, of the meaning of various features of these foundations by comparison with

- 1)Facts found in research material mentioned above.

- 2

- 2)Similar building complexes in Williamsburg and surrounding area.

- 3)Architectural features uncovered in the course of the restoration of the house and kitchen.

- 1.Description of foundation walls, paving, etc. found by excavation on property.

- IV. CONDITION PRIOR TO RESTORATION

- 1.Description of house, outbuildings and grounds at time restoration was begun.

- a)The house

- 1)Exterior

- a)East, south, west and north elevations described (wings, porches, walls, chimneys, windows, doors, etc. with enumeration of materials).

- 2)Interior

- a)Description, room by room, of condition and outstanding features

- 1)first and second floors

- 2)attic

- 3)basement

- a)Description, room by room, of condition and outstanding features

- 1)Exterior

- b)The kitchen

Same treatment as for house - c)

Other outbuildings and grounds.

- 1) Size of plot at beginning of restoration

- a)The house

- 1.Description of house, outbuildings and grounds at time restoration was begun.

- V. ANALYSIS OF HOUSE. OUTBUILDINGS AND GROUNDS AS RESTORED

- 1.The house

(Here I will follow the outline prepared by Lawrence Kocher for the treatment of restored buildings. I will omit the portion entitled "Masonry" and such other items as will already have been covered in the foregoing outline such as, under "Plan Type", what additions were made and relate evidence of archaeology and research.)

- 1.The house

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

CARTER-SAUNDERS HOUSE AND BRICK QUARTERS

Block 30, Colonial Lots 333, 334, 335, 336

THE CARTER-SAUNDERS HOUSE was the town house of Robert Carter of Nomini Hall, and of other prominent personalities. It was given special prominence by its location next door to the Palace and for a brief period served as the house of the Royal Governor.

THE CARTER-SAUNDERS HOUSE was the town house of Robert Carter of Nomini Hall, and of other prominent personalities. It was given special prominence by its location next door to the Palace and for a brief period served as the house of the Royal Governor.

CARTER-SAUNDERSRobert Carter HOUSE

(Restored)

Block 30, Col. Lots 333, 334, 335, 336

The Carter-Saunders House was restored under the direction of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, architects, whose resident architect was Walter Macomber.

Those who participated in the field, drafting and supervision include A. E. Kendrew, S. P. Moorehead, George S. Campbell, Thomas Waterman and Richard A. Walker. Archaeological drawings are by H. S. Ragland and James Knight.

Reconstruction was started July 7, 1931.

Reconstruction was completed February 4, 1932.

Note: The Carter-Saunders property has been considerably modified since this report was written, so that the report will require revision.

This report was prepared by A. Lawrence Kocher and Howard Dearstyne for the Department of Architecture, (Architectural Records). July 26, 1949

CARTER-SAUNDERS HOUSE

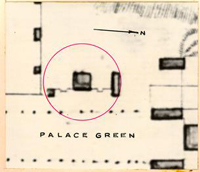

Block 30, Colonial Lots 333-336, Building No. 13

A location such as that of the Carter-Saunders House on the west side of the Palace Green in close proximity to the "Governor's House" would surely have been one of the most desirable in Williamsburg in the eighteenth century. It is not surprising therefore that the house was occupied successively by as distinguished a list of owners and residents as any dwelling in the town, and all of these must have contributed to its elegant development.

OUTSTANDING VIRGINIANS

The first owner of whom there is a definite record was Charles Carter who came into possession of the lots sometime before 1746. Carter was the son of the fabulous proprietor and planter, Robert "King" Carter, and who spent several consecutive months of each year in Williamsburg as a member of the Assembly.

One of the next owners of the property was Dr. Kenneth McKenzie, a famous surgeon-apothecary, who built a shop or storehouse on the lots, from which he sold drugs and various other articles. Dr. McKenzie had lived in the house for four years, when in November, 1751, Robert Dinwiddie arrived with a commission as lieutenant-governor. The Palace had for some time been in a "Ruinous Condition" so that McKenzie's home was itself chosen as a temporary residence for the governor while the necessary repairs were made to the Palace.

Robert Carter Nicholas, the Treasurer of the Colony, bought the house in 1753 and lived in it eight years. In 1781 1761 he sold it to 2 his famous cousin, Robert Carter of Nomini Hall in Westmoreland County, a member of the Council and judge of the General Court of Virginia. Carter was a leader in the official and social life of Williamsburg. George Washington and Lord Botetourt dined at his home in 1769 and Lord Botetourt also visited it the day before his last public appearance in Williamsburg. In the early part of 1772 Carter returned with his family to Nomini Hall and in 1776 Dudley Digges, a member of the Council during the Revolutionary period, moved into the house and occupied it for some years.

In 1803 the house was purchased by Robert Saunders, a distinguished lawyer, who left it on his death to a son of the same name. Robert Saunders, Jr., son-in-law of Governor John Page and president of the College of William and Mary, held the property through the Civil War period, during which it was plundered by the Union Army. In 1872 it came into possession of the College.

Governor Dinwiddie remains the most prominent resident of the Carter-Saunders House, although nothing is known of what took place on the property during his temporary occupancy. The fact that some of the most outstanding Virginians of the period lived there in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries explains its character and the many alterations which were made to it. Probably each owner changed the house and grounds to his own taste. The natural slope of the land behind the house lead to its development as a "falling garden", second only to that of the Palace in beauty and extent.

DESCRIPTION OF THE HOUSE

The Carter-Saunders House represents, unlike the Barlow, Bracken or Lightfoot Houses, which were dwellings of middle-class citizens, the 3 somewhat more spacious and elaborate town house of a gentleman, who maintained an estate in the country but who spent several months of the year in Williamsburg as a member of the Assembly or an other public business. In the form which it assumed in the latter part of the eighteenth century—that is, of a two-story house of rather ample proportions (30'-0" x 45'-6") with outbuildings at either side (a kitchen some 40' to the south, what was apparently a servants' quarter at approximately the same distance to the north, and with other outbuildings elsewhere on the lot) it was in many ways the equivalent of a plantation establishment built within the confines of the city. From what is recognized to be its "first construction period"* this building or building-complex underwent a succession of changes in the course of which alterations were made to the foundations, the building was partially enveloped in brick, and additions—porches, a leanto and a connecting link to a north dependency were made. Throughout all of these construction changes the original plan of the house proper remained almost completely unaltered.

The Carter-Saunders House was not restored to its original first form, when the building was cellarless and had, so far as was known at the time of restoration,# only a single outbuilding at the north. It 4 was restored, rather, to a second period condition, which was believed to approximate its fullest eighteenth century development, when changes had been made to this first form—two lateral wings had been added; a basement had been dug and basement windows had been provided to light it as well as a bulkhead and steps on the south side to give access to it. To this restored colonial structure a one-story porch was added on the west side, a feature which did not exist in the eighteenth century, but which was included as a concession to the requirements of modern living. In its present restored form the house may be likened to the Archibald Blair House in Williamsburg, although the latter has an A roof with gable ends, and also to the neighboring Wythe House, whose plan in many respects resembles that of the Carter-Saunders House. In a search for similarities we note that the roof form closely resemble that of Ampthill in Chesterfield County.

THE HOUSE APPEARANCE

The Carter-Saunders House as restored is a two-story wood building with a hipped roof of double slope*, a roof which is related to the 5 gambrel type roof in having this double slope, but which differs from it in that it occurs on all four sides rather than on two only. Two chimney stacks penetrate this roof at either end of the roof ridge. There are no dormers in the roof.

The front or Palace Green facade of the house proper is symmetrical, and has on the first floor a central hooded doorway flanked at either side by a single 18-light window. Three 18-light windows in the second story line up with the first floor windows and the doorway below the two basement windows in the brick foundation wall fall directly beneath the first floor windows. A porch, consisting of a stone platform and four stone steps supported on brick foundation walls gives access to the house. The porch has at either side a wrought-iron railing which is confined to the platform and does not continue down the steps.

Attached to either side of the building with their front faces flush with the front facade of the house are two gable-roofed appendages or wings, each having a single 15-light window in its north side. These 6 wings have been made to appear as later additions by a number of design devices. The foundations of the wings, for example, rise considerably higher than those of the house and are separated from them by a distinct vertical joint. The weatherboarding of the appendages does not line up with that of the house and is separated from it by the cornerboards of the house which are carried down to the foundation. Finally, the sills of the windows of the wings do not line up with the sills of the first floor windows.

The front facade of the house proper, with its rather considerable length of 45'-6" is unusual in having only two windows on the first floor and three on the second. A few other houses in Williamsburg, such as the James Geddy, St. George Tucker and Allen-Byrd Houses (south front), do have this arrangement of openings, but facades with four windows and a central doorway below and five windows above, are much more customary. The rear or west front of the house differs from the east front, as a matter-of-fact, in having this more usual arrangement. This facade also has a shed-roofed porch which extends very nearly the entire length of the house and which was incorporated in the design, as was stated above, for the convenience of the occupants.

The north and south fronts of the house are basically similar. Projecting from each facade at its north end is the one-story wing mentioned previously. These wings have pedimented ends with modillion cornices which are reduced versions of the main cornice, and single 15-light windows. The north wing, which serves as a kitchen, has been made deeper than that at the south by a shed addition on the west side, in which an entrance stoop to the kitchen and an alcove enlargement of this room have been incorporated. 7 A vertical type, gable-ended bulkhead has been built on old foundations on the south side of the house to afford access to the basement. The fenestration of the north and south facades proper is identical, and consists of three 18-light windows in the second story and two windows of this same size in the first, placed directly under the center and south windows of the second story.

The position of the interior foundation walls in the basement corresponds closely with that of the partition walls of the first floor, so that, since these foundation walls derive for the most part from the first construction period, it is safe to assume that the first floor plan has remained essentially unchanged since the house was originally built.

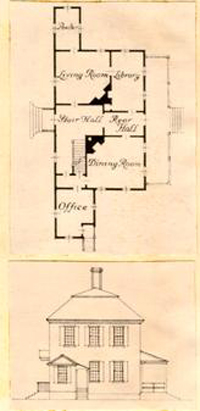

ITS TWO-ROOM-DEEP PLAN

The first floor plan resembles in its essentials the plan of Mount Pleasant in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia. It has an L-shaped hallway, the "vertical" arm of which runs through the house from front to rear while the "horizontal" arm forms a stairhall at the right of the entrance doorway. The stair to the second floor rises on the west wall of the stairhall and a stairway to the basement runs under this along the same wall. A vestibule intervenes between the end of the stairhall and the kitchen in the north wing. The central hallway is divided by an archway about midway in its depth into a front hall and a rear hall which is somewhat narrower.

The first floor, exclusive of the wings, has three rooms, two at the south and one at the north of the central hallway. The southeast 8 room (the dining room) and the northwest room (the living room) are nearly square and of nearly equal size, while the southwest room (the library) is rectangular in shape. There is a fireplace in each of these rooms; two corner fireplaces serving the living and dining rooms respectively are built in the inside angles of these rooms and are nearly but not quite lined up with each other on the horizontal axis of the building. The library fireplace is built in the south side of the triangular mass of brickwork forming the corner fireplace in the adjoining living room. A rectangular room, called a "powder room", occupies on the south side a position corresponding to the kitchen on the north and is entered from the living room.

Except that space in the hallway has been taken for two baths and a line of closets on the south wall, all additions made for modern convenience, the number and disposition of the rooms of the second floor remain as they were in the eighteenth century. There are three bedrooms which correspond in size and position to the three rooms of the first floor and fireplaces in the same locations as those of the story below serve these three rooms.

FURNISHINGS

The Carter-Saunders House was at the time of its occupancy by Councillor Robert Carter a richly furnished house, as the orders sent by him to his London merchants between 1761 and 1771 indicate. Carter ordered much costly and elegant furniture and silver tableware; silk and worsted damask curtains "for a room ten feet pitch"; three marble hearth slabs, four feet by eighteen inches, "to be wrought very thin"; four large brass sconces; two glass globes for candles to light a staircase, 9 and a Wilton carpet. He also ordered wallpaper* "to hang three parlours, round the four sides of one parlour measures fifty-five feet, from the floor to the ceiling eleven feet." For the first parlor he wanted a good paper of crimson color; for the second parlor a better paper, a white ground with large green leaves. The third parlor was to have the best paper, a blue ground with large yellow flowers.# Measurements were also given for the papering of a stairhall and two passages.

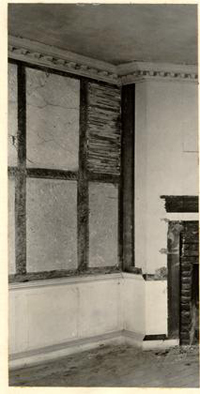

Aside from the evidence afforded by these orders, structural evidence was found at the time of restoring the house to indicate that 10 two, at least, of the rooms had at one time been "hung" with paper. The removal of a layer of plaster from the walls of the northwest room (dining room) and the southeast bedroom, above the wood dado, exposed a wood framework upon which paper had at one time undoubtedly been hung. This framework, which formed a pattern of rectangles, consisted of vertical studding and horizontal wood braces placed from stud to stud midway between the top of the dado and the cornice and at the upper edge of the dado and the lower edge of the cornice. The rectangular spaces between the wood members had been plastered flush with the framework. The wall paper, applied to cloth, had doubtless been hung as damask was hung in the eighteenth century, by stretching it over wood strips to form panels, which were then attached to the structural framework by nailing. The paper, in other words, was not pasted to the plaster as it is today but was held free of the wall, the plaster infilling serving the purpose of insulation only.

Left -- View of Corner of Dining Room showing framework to receive plaster.

Left -- View of Corner of Dining Room showing framework to receive plaster.

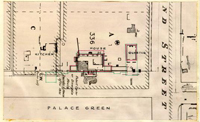

Composite Plan of Carter-Saunders House and Outbuildings, showing, super-imposed upon the excavated foundations, 1--the House and Quarter as restored (red lines), and 2-- the building as shown on Frenchman's Map (green lines). Area C was excavated in the Spring of 1949.

Composite Plan of Carter-Saunders House and Outbuildings, showing, super-imposed upon the excavated foundations, 1--the House and Quarter as restored (red lines), and 2-- the building as shown on Frenchman's Map (green lines). Area C was excavated in the Spring of 1949.

WHAT THE ARCHAEOLOGISTS FOUND

The foundations uncovered by archaeological excavation on the Carter-Saunders property are probably the most complex and they are in many ways the most interesting of any private residence in Williamsburg, but they raise many questions which still remain unanswered. The main body of the archaeological work was done in 1931 by H. S. Ragland with the assistance of James Knight. As was stated previously, however, the unavailability for excavation at this time of the modern Foster lot, which occupied what in the eighteenth century was the northern portion 12 of the Deane property and the southern part of colonial lots 333-336, forced postponement of the investigation of this southern strip of the Carter-Saunders property until the spring of 1949, when it was excavated by James Knight. Knight discovered there the remains of a kitchen and a bake house.

At the outset of his archaeological report of April 24, 1931, Ragland states that it is impossible to date with accuracy the numerous foundations which he discovered, and that only the chronological order in which they were built can be given. He concludes that the house passed through six construction periods and he describes these in his report and illustrates them in the drawings which accompany it:

Period No. 1

This house at this time had no basement since the outside foundation walls were not deep enough to accommodate one. The two main chimney foundations did, however, extend down to what is now the basement floor level. The foundations of an outbuilding, probably a quarter for servants, existed northwest of the house.

Period No. 2

A basement was dug to a depth about two feet deeper than the outside walls, leaving a bank of earth on the inside to avoid weakening the foundations. Basement entrances were built on the south, west and north sides of the house and basement windows were cut through the original walls. At the south side of the house near the front corner and opposite this on the north side, foundations were built at this time, according to Ragland, which were those of gable-roofed one-story additions which extended to outbuildings lying north and south of the house. There is doubt as to the validity of Ragland's interpretation of these foundations. His statement that the Rochambeau map of 1782 shows the main house joined 13 by lateral outbuildings is not supported by an examination of this map. The Frenchman's map, furthermore, made at about the same time as the Rochambeau (1783) shows the main house with elongated outbuilding at the north and a square one at the south, but with no connecting links.*

Period No.3

An 8" retaining wall, which still exists, was built in the basement about 2 ft. inside the exterior walls, apparently to keep the earth sides from slipping and undermining the outside walls. The house was also partially enveloped about this time by a "veneer" brick wall, approximately 1'-6" in thickness, which was likewise built, undoubtedly, to strengthen the foundation walls. This wall, which was carried from a depth of about 2 feet below the bottom of the original foundations upward the full height of the house walls, covered the west face of the house and about two-thirds of the north and south sides, stopping at a point where the lateral wings projected from these walls. A supplementary wall of wood was built above the wings, flush with the surface of the brick enveloping walls. The east exterior wall of the house was left undisturbed. Water had evidently begun to accumulate in the basement for a brick drain, penetrating the foundation wall at the southwest corner, was built at this time.

Subsequent Periods.

During the remaining construction periods, a number of changes and additions, chiefly external, were made which will be listed here briefly:

- A two-storied, pedimented front porch supported by four circular, stuccoed, brick columns was built over the sites of three earlier porches.

- A shed-roofed porch of two stories was built at the rear, running from the northwest corner very nearly to the southwest corner of the house.

- A one-story shed addition, housing two rooms which connected with the present dining room and stairhall respectively, was erected across the north side of the house.

A two-story gable-roofed outbuilding was constructed north of the house more or less in line with the present brick quarter. This outbuilding projected several feet beyond the front facade of the house, and was connected to it by a one-story covered passageway. The outbuilding and connecting passageway, which are shown in an old photograph made some 50 years ago and reproduced herewith, had disappeared before the restoration of the Carter-Saunders House was begun.

CARTER-SAUNDERS HOUSE

Block 30, Colonial Lots 333-336, Bldg. 13

EXTERIOR

PLAN TYPE

The Carter-Saunders House has a two room deep plan with a center hallway, without stairs. On one side there is a single room (dining) and a secondary hallway with stairs leading to the upper floors. Two rooms are on the other side of the hallway.

The plan resembles the Wythe House arrangement, excepting for the stairway location. It is also a diminutive version of the Governor's Palace of the days of Thomas Jefferson. Mount Pleasant, a town house in Philadelphia, duplicates closely the plan of the Carter-Saunders. The latter represents the dignified town house of a plantation owner, such as was Robert Garter, at one time a member of the Virginia Council and who required a place of residence near the colonial capitol.

DIMENSIONS

The dimensions of the house, as restored, (the veneer of late brickwork removed), is 45'-6" in over-all length by 30'-3" in depth. The 17 plan size, given here, does not include the end appendages, both to the north and the south—indicated on the plan as kitchen and as powder room.

BRICKWORK

The use of brickwork for the original Carter-Saunders House occurs as foundation walls, for chimneys and their footings, basement partitions and isolated piers, a vault, possibly of later date than the first house form, fireplace hearths and miscellaneous out-of-doors paving surrounding the house, and also steps. Brick was again used for low retaining walls within the basement. These inner walls were built at an undetermined date when a cellar was excavated and a bulkhead built at the south side of the house. An opening in the west wall with steps to the basement dates from the same period as the bulkhead entrance.*

BOND

The original and old foundation wall of the house was laid in Flemish bond. Interior walls and the bases of chimneys, as shown below the first floor level, are of English bond.

Color and Texture

The color of brickwork ranges from a brownish-red to a dark gray. The predominating wall color is a gray-red. There is almost a complete absence of glazed headers. Foundations such as these were most often without patterning produced by glazed headers, mixed with regular 18 bricks. Most brickwork of the basement interior was found to be white-washed, a finish that obviously was frequently added for both light and cleanliness.

The brick texture is irregular. The surface finish of these brick resulted from a crude shaping in wooden molds. The examples of brick examined on the main house were without noticeable deterioration. They are in relatively good condition.

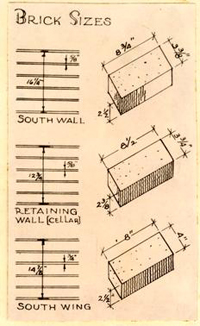

Brick Sizes and Jointing

Brick sizes vary from 8 inches to 8 ¾" in length, width 3 3/8" to 4" and 2½" to 2 3/8" in thickness.

Measurements made of 5 brick courses total 16¼". The tooled brick jointing of mortar was found to measure 5/8" to ¾" in width.

No use was made of rubbed brick since such special treatment was rarely given to the brickwork of foundations. It should be noted that the original house had no basement windows. The addition of windows by openings made in the brick wall, occurred at the time when the cellar was excavated and a bulkhead added, some time before 1800.

Mortar.

The mortar is composed of oyster shell lime with local sand.* The mortar color was gotten by breaking apart a fragment of discarded mortar. This revealed a tawny gray color which, in general, is characteristic of local Williamsburg oyster shell mortar.

Foundations

The old house foundations were a brick and a half or 13" in thickness. This is customary wall dimension for a wood-frame superstructure. Because of the sinkage of some brickwork and the unevenness of floor levels, the old foundation was strengthened in places by masonry underpinning and by some rebuilding, using the old bricks. The policy of utilizing the existing and weathered materials and avoiding intrusions of new work is evidenced by the often repeated instructions on the architectural drawings for this house, such as: "repair old brick work"; "remove antique window frame and relocate in original opening"; "old [basement] grille refixed."#

Chimneys

There are two chimney stacks, located within the center area of the house, rather than at the ends of the plan as was a common tradition. While there was no fireplace in the basement, we can perceive at 20 this level, the corner fireplace shape of both the dining and living rooms above. Similar fireplaces are also located on the second floor.

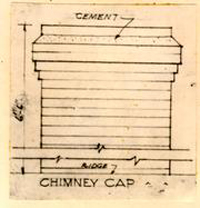

The two chimney stacks penetrate the roof and are at balanced locations. These were found, on examination by the architects, to be considerably altered through repairs. They were both rebuilt and follow precedent for chimney tops, of other Williamsburg houses of pre-colonial days. Of the two chimneys, neither is centered on the roof because of the staggered location of the chimney stacks. Above the roof the south chimney is square and contains 4 flues, serving two fireplaces on the ground floor and two on the second. The north chimney is T-shaped and contains 3 flues joined to one corner fireplace in the dining room of the ground floor, one bed room fireplace above and in addition a flue for the basement furnace. The chimney, as rebuilt, was laid with a variant of Flemish bond. It has a cap formed of 2 projecting corbel courses beneath a band of two brick courses. These four projecting courses are surrounded by a double course of brick as illustrated herewith. The Lightfoot house chimney (as rebuilt as a replica of its original one is cited as precedent; --also a chimney in New Kent County (Rose Garden) located and measured by Walter Macomber and considered to be of the third quarter of the eighteenth century.

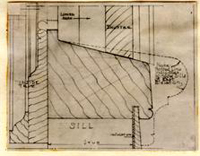

Hearths

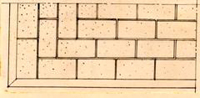

All fireplace hearths and fireplace floors are either old hearths found in place or made of old brick laid with the conventional Williamsburg pattern, in sand, on their flat sides. This typical brick pattern is illustrated in the adjoining sketch.

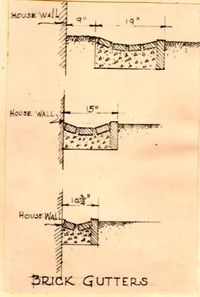

Brick Gutters.

The archaeological drawings do not supply an answer to the question whether roof-edge gutters of metal or ground-level gutters of brick existed as a part of the original Carter-Saunders House. The gutters and downspouting found on the house at the time of its restoration were recognized as modern and so were removed: While roof-edge guttering of eighteenth century Williamsburg was not unknown, abundant precedent has been found for brick guttering at the base

BRICK GUTTERS

22

of walls, including fragments of gutters found at the side of the flanking buildings of the Palace, also at the base of the walls of the unrestored Timson House. For a full discussion of the use of gutters of brick, see architectural report on The Dr. Barraud House.

BRICK GUTTERS

22

of walls, including fragments of gutters found at the side of the flanking buildings of the Palace, also at the base of the walls of the unrestored Timson House. For a full discussion of the use of gutters of brick, see architectural report on The Dr. Barraud House.

There are three kinds of brick gutters used on the restored Carter-Saunders House. These appear as illustrations herewith. All brick for gutters is laid on a subbase of concrete. The gutter width varies from 10 3/4" to 19 ¼ inches. The gutter at the front and rear of the main house is placed 9" from the brickwork of foundations, apparently with the thought that the eaves drippings would be gathered more effectively at that position. It also permitted planting of vines, close to the house.

All gutters slope toward drains which, in turn, are joined to the storm sewer.

Other Brickwork

There were diagonal pathways of brick paving leading to the front entrance, uncovered by A. F. Perkins in 1929. These became the basis for restored pathways of brick added as an extension of the system of sidewalks. Archaeological Drawings, dated April 22, 1931, should be examined to note the composite nature of footings and extensive broken brick paving recorded at the time when the restoration of the house was undertaken.

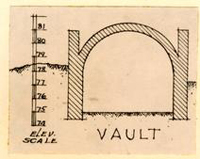

Brick Vaulting

A brick vault was found beneath the remains of the passageway extending northward from the north-east corner of the house. This vault 23 is considered an addition made at the time when the connecting passages were built, possibly in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. The vault was accessible from the basement and was probably used as a storage place for wines and farm produce. The brick vault measures 6'-7½" in inside width by 15'-4" in interior length. The ceiling height at crown of vault is 6'-0". The thickness of the vault shell is 9".

Such underground vaults were of fairly frequent occurrence in the Virginia colony. They were intended primarily for food storage but are known to have served on occasions for the safe keeping of records. They were usually unlighted but were frequently ventilated. There was a well-founded tradition that a vault beneath a first floor made the house more safe from fire than one with a wood framed floor over the cellar.

EXAMPLES OF SIMILAR VAULTS IN WILLIAMSBURG OF THE SAME PERIOD AS THE CARTERSAUNDERS HOUSE.

- 1.Palace - vaults mentioned in the inventory of the Palace.

- 2.King's Arms - old part of basement was noted as having a single continuous vault.

- 3.Wren Building - located under the front of building and not to be confused with burial vaults.

- 4.Waller (Morecock) House - A small vault is said to have joined the basement of the Morecock House with the basement of a kitchen. This was visited by the writer of this report in 1948. It was noted that entrance to the vault had been "bricked up".

MASONRY

In writing of stonework for a house in Williamsburg we have reference to cut "building stone" of a rather costly kind, such as "Portland" of "Purbeck", imported from England, or more rarely from some discovered quarry within the Virginia colony. There was no deposit of stone found in the York-James-Peninsula area. Stone was in demand for building and for gravestones. This had to be imported to this region from elsewhere.

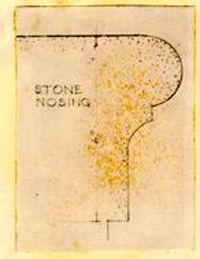

A native building stone is found as platform and steps at the front entrance of the Carter-Saunders House. It is from Acquia Creek on the Potomac, near Fredericksburg, Virginia,* a deposit mentioned by William Byrd in his recorded travels.#

The porch platform and steps are each 6" in thickness and are supported on a base of brickwork. Each step laps over the one below. 25 All stonework (platform and steps) is edged with a half round molding, 1½ inches in thickness. Beneath this nosing there is a small fillet and cove. The steps have a fan-like spread at the bottom. The design of the steps is based upon the steps of Tuckahoe in Goochland County and they also resemble the steps of the later James Semple House. Other supporting precedent for both the steps and railing are found at the north side of the President's House of the College of William and Mary, shown on the Bodleian Plate view of the President's House.

The reader of this report should be reminded that while most features of the Carter-Saunders House proper are old and authentic, whether of design, plan or materials, the entrance steps, doorway, and hood alone are reconstructed, using contemporary specimens of Virginia stairs as a basis for their design.

WROUGHT IRON RAILING

A 3' high railing of wrought iron was installed during the restoration at the two ends of the platform. The railing consists of a 1" square corner post of iron and 7 vertical bars 3/8" x 3/4" in section. The President's House at the College, (north porch) served as the model in detailing the railing. The Carter-Saunders iron work differs in having no hand railing for the descending steps. A brass finial ornament is centered over the two square angle posts.

ROOF

The Carter-Saunders roof is termed a hip-roof, but it has a secondary roof of lesser slope forming a low rectangular pyramid at the 26 top. The hip roof and the top are separated by a set of moldings. This roof had originally, it is believed, * an open deck, as discussed elsewhere, designed to gather rain water and provided with gutters and conductors to divert the water to a cistern. We know from frequent documentary references that cisterns existed in the town as a source of soft water for the laundry.

Slope of Roof

The angle of the hip roof (lowest part) with the horizontal, is 39 degrees. The slope at the top is 20 degrees.

There are other roof slopes to be recorded, such as for the pediment of the main entrance hood, which is 30 degrees. This same 30 degree slope also applies to the pedimented roof of the two small end pavilions, as viewed from the north and the south.

The roof is covered with asbestos-cement shingles which were specified at the outset of the Restoration as a substitute for wood shingles which at one time covered most roofs of Williamsburg. The substitute was adopted, for fire safety, and as was required by town regulation. The use of substitute shingles and their composition is discussed at length in the files of the Architectural Department (Records). The asbestos shingles of the Carter-Saunders roof have tapered sides and rounded butts. Their color is a gray-brown to match that of old and weathered wood shingles.

EXTERIOR WALLS

The house was framed in a conventional eighteenth century manner, briefly described as having a heavy framing sill 9" x 12", placed over the 27 brick foundation. Corner posts are 4" x 6", while upright studs measure 4" by 2" to 3". The corners of the house are stiffened by diagonal braces, mortised into the sill and corner posts. Eighteenth century framing techniques, with mortise and tenon fittings, apply in the joining of all the framing members.* Since these members are attached by the aid of oak pins, one can readily understand the boast of early builders that an entire house was sometimes fashioned without wrought nails.

To this sturdy frame was attached the outside sheathing, consisting of tapered weatherboarding.# This "feather-edged" weatherboarding was found to have an uneven exposure that averages approximately 6". The following is a notation of measurements for boards, made at the site by the writers of this report, namely, 6", 6¼", 5½", 6", 6¼", 5 ¾", 5½", 6". All weatherboarding has a typical ½" bead at the lower edge.

Much of the weatherboarding is original, and because of its location behind a 13" brick wall, it has remained in surprisingly well-preserved condition. The weatherboarding as found was repaired, loose boarding renailed in places and some patching by the use of boards from old buildings. Nails similar to those found to have been used were adopted. A study of nailing seems to indicate that a 2'-0" stud spacing held for the original framing. Because of repairs and strengthening of the wall there is now an irregularity of studs.

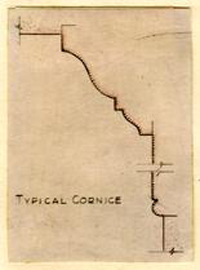

CORNICE

The main house cornice probably disappeared at the time when the brick casing to three sides of the house was carried out. The present restored cornice is new. Its modillion character and its detailing are based upon the existence of such a cornice applied to the brick wall, supposedly of the fourth period of construction. It is probable that a cornice applied at that time would follow the profile and nature of the cornice that had existed before the brickwork was applied. It should be noted, however, that where we have an original weatherboarding wall, as at the front, (east elevation) the cornice was of extreme simplicity, apparently a carpenter replacement, and without modillions.

The cornice as restored is a close replica of known old examples in the locality, such as the cornice of the Peyton Randolph and the Archibald Blair. Almost all houses of size within the town were graced by a similar bracketed cornice, varying only in projection and in the design of the modillion. The Wythe house, Ludwell-Paradise and the St. George Tucker house all had modillion cornices.

The small end buildings, designated as pavilions, are reconstructed with a cornice alike in appearance but proportioned in size to the lesser wall height.

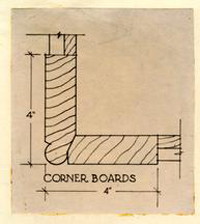

CORNER BOARDS

These are at the four corners of the house and at the outer corners of the two reconstructed pavilions. Corner boards are two directional and are based upon the old corner boards found in place at the southeast angle 29 of the house. This became the pattern for all corner boards. See Photo #127, Progress photographs, vol. 1.

MAIN DOORWAY

The frame of the front doorway with its double-molded trim is old, including the transom, while the door itself was found to be of the late nineteenth century. This door was replaced by a reproduction of an old door. It was obvious to the restorers that the door opening with its 3'-7½" width must have had a double door. Doorways of the locality were studied in the light of the doorway dimensions and the period. A door design was decided on based upon the main double doorway at Wilton, Henrico County, Virginia. Both have a four light transom above the door, and their frames and treatment are alike. Each door valve has four panels as described in our door chart.

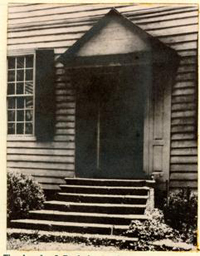

Doorway Hood

In glancing at the front facade of the Carter-Saunders House from Palace Green, one's attention is focused upon the doorway and its pedimented hood. The hood is a natural complement of the doorway and serves a practical purpose, providing some shelter from rain and at the same time it adds an architectural feature with a positive attraction to the design.

Since this type of hood occurs three or four times among the restored houses of Williamsburg,* it is of some importance that we record 30 the origin of the motif. The Tuckahoe (Goochland County) garden entrance was used by the designer of the Carter-Saunders hood. The Tuckahoe original and the derivative Carter-Saunders hood are alike, not alone in the treatment of the hood but the stone porches and steps of each are similar. Both have a wood paneled ceiling beneath the hood. The unusual manner in which the crown molding extends horizontally across the base of the pediment is also repeated in the Carter Saunders example. This is not a correct classical use of pediment moldings such as are found in carpenter's handbooks, but we note a native and frontier character, such as was referred to by Hugh Jones who spoke of the buildings of the first settler being "adjusted to the nature of the country."

The hood of Tuckahoe, shown above, was the design inspiration for the hood of the main doorway of the Carter-Saunders House (below).

The hood of Tuckahoe, shown above, was the design inspiration for the hood of the main doorway of the Carter-Saunders House (below).

An early photograph of the President's House at the College shows a hood with its base in a line with the belt course at the second story level. The hood projection here is 31 slight and its purpose is more purely a decorative one. The south doorway of the President's House and also the two entrance doorways of Brafferton repeat (in restoration) the hood of this early photograph.

Some of the rubbed brick pediments of early Virginia churches, such as Vauters, Abingdon and Lamb's Creek suggest the unsupported pediment. More amusing than convincing as a basis for the design is the unsupported porch pediment of the old Court House.

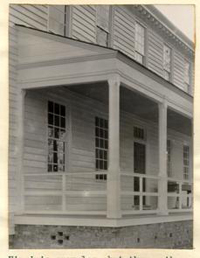

REAR PORCH

A rear porch extends nearly across the entire length of the west side of the house. It was added at the request of a tenant and is to be thought of as a convenience, not as an integral part of the original Carter-Saunders House.

There is a reasonable basis for adding a porch at the west side, since one existed there during the nineteenth century. Details of that late porch were repeated and are recognized in the design as developed and built by the architects of Colonial Williamsburg. For example, similar square posts with chamfered corners support a semi-classical frieze and cornice. These details, it should be noted, do not repeat the exact appearance of porch parts from recognized Virginia examples, but they rather reveal their added nature; namely, that the porch is an addition.*

KITCHEN PORCH

This porch together with its extension of shed roof are both recognized concessions to the convenience of a twentieth century tenant. Here as with the larger rear porch, the design elements are not deceptive. They can be—and should be—recognized as additions. In other words, the parts that produce the porch, (the moldings and railings) have been created so as to harmonize with the house, but not to appear as restored features of the original.

DORMERS

Attic dormers existed at the time when the restoration was started. These were obviously modern and therefore were removed.

BULKHEADS

The basement entrance with an A roof bulkhead is situated at the south side of the house, near the south-west angle. The brick steps and enclosure are old but they are an addition made during the second period of the house,--at the time when the basement was excavated.

There is a concealed brick foundation which terminates about two inches above the ground level. On this foundation the bulkhead is framed and faced with flush beaded boards of random widths. Because of the scant slope of the bulkhead roof, an arch (segmental) extends into the gable end, where there are two batten doors, provided with 20 inch strap hinges. 33 At the roof edge of the east and west sides there is a 2½" crown molding and fascia, while the barge board of the south side (gable end) is a flat board, beaded at its lower edge. This board tapers from 4" to 3½".

Precedent for the bulkhead is in part the Carter Saunders one, although this was modified and in a fragmentary condition. Mt. Prodigal has a similar bulkhead which, with its details, establishes the authenticity of this restored basement entrance.

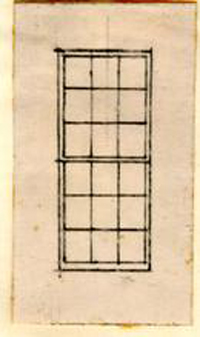

WINDOWS

All sash of the restored Carter-Saunders House are new. There were several old and original window sash which served as a model in replacing the old with new ones. On the other hand, most of the window frames are old. These were repaired and some few replaced by new frames or sills, copied after the original ones. Instructions on the working drawings repeat, again and again, "Repair frame."

All windows had heavy square sills, excepting on the front (East) elevation where molded sills were found and followed.

The sash of the second story are the same as for the first floor. In both locations, the sash are double hung, (lower sash movable, upper sash fixed), three lights wide and six high; glass size is 10" x 11".

The window trim is 4½" in width and is double molded and 6" in width on the inside.

SHUTTERS

These occur on all of the windows of the house, including the end pavilions and rear porch. Many of the shutters are old and original, having been salvaged from the house as it was taken over for restoration. These shutters were repaired, while new ones that were required repeated precisely their construction and design. All shutters have mortised frames, without an intermediate rail. The slat edges are rounded and spaced 7/16" apart. 3/8" wood pegs join together tightly the top and bottom rails and the stiles.

CARTER-SAUNDERS HOUSE

Block 30 - Colonial Lots 333-336 - Building No. 13

INTERIOR

FLOORS

The flooring throughout the house, with the exception of that of the reconstructed north and south wings, which is new, is old yellow pine flooring found in place at the time the house was restored. This was repaired and reused. The floor boards vary in width from about 3¼" to 8"; they are joined by tongue and groove joints and are face-nailed with use of old type nails. The floors are finished with wax in accordance with the eighteenth century practice for such floors.

The wood flooring of the kitchen and the two bathrooms is covered with linoleum.

WALLS & CEILINGS

All old plaster in the house was removed and all ceilings and walls were replastered except for those portions of the walls where a wood dado or overmantel sheathing or paneling occurs. The plaster was applied on metal lath and given a wavy surface finish to resemble eighteenth century plaster. In the dining room and southeast bedroom, where the wood "framework" to which, at one time, wall paper was hung, occurs (see previous description), this framework was plastered over.

INTERIOR TRIM

Most of the interior trim is old or copied after old trim found in the house at the time of its restoration. The cornices, chairrailings, 36 bases and dados are listed below according to type, the rooms in which they occur are given, and the fact of their being old or new is indicated.

CORNICES

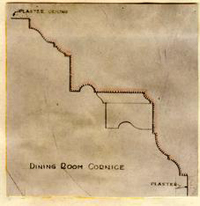

Old cornices of this type were found in the living room, the study (southwest room, first floor) and in the northwest bedroom. Reproductions of the type were placed in the hallways of the first and second floors and in the southwest bedroom.

Wood cornice of dining room --old, repaired.

Modillion blocks 1½" wide and spaced 4 7/16" on centers.

37

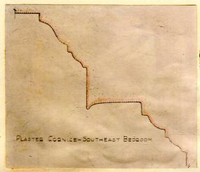

PLASTER CORNICE-SOUTHEAST BEDROOM.

PLASTER CORNICE-SOUTHEAST BEDROOM.

Original plaster cornice

in southeast bedroom--repaired.

Chair railings

An old example of this chair railing type (type A) was found in the southwest bedroom, and another in the stairhall leading from the second floor to the attic. These were left in place and repaired. They were followed in the design of the new chair railings in the hallways of the first and second floors. The backband is 5½" high and the moldings return against the backband at window and door openings, mantels, etc.

38An old railing of this type (type B); without the backband, was found in the southeast bedroom and was repaired and retained. A new railing, patterned after it, but with 5½" backband added, was used in the living room.

Baseboards

The baseboard shown at the left was used in all hallways and in those rooms where no wood dado occurs (living room, southeast and southwest bedrooms). It is new in all cases. This is the typical beaded baseboard used in restoration work in Williamsburg.

Wood Dados

Three rooms in the house, the dining room, northwest bedroom and study, have wood dados (chair rail-height wainscoting), and a dado is also found in the stairhall. These are all old dados, found in place, which have been repaired and retained.

The single example of a paneled dado is that found in the stairhall, where it was used on those walls from the first floor to the second floor landing along which the stair runs. The spandrel beneath the initial flight of steps on the first floor is likewise paneled. The dado cap is a molded cap with rounded top, which recalls the design of the stair handrail.

The dining room dado has an unusually heavy molded top rail and base (see sketch), both of which are returned at window and door openings and at the mantel. The dado itself is an unbroken plane surface consisting of unmolded squares of wood set flush with the stiles and rails.

The dados of the study and southwest bedroom are similar in character? though they differ in height; the top rail of the latter rises some six inches or more above the window sills and that of the former being on a level with them and forming the molded front edge of the sills. The rails and bases have moldings which are much lighter and more delicate than those of the dining room. The surface of each dado is composed of horizontal, unbeaded? flush boards of random widths. Both dados are interrupted at the windows and are stepped forward slightly to form "broken front"? surfaces beneath the sills.

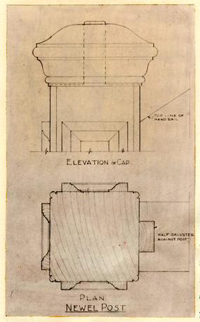

MAIN STAIR

The main stair from the first floor to the attic is the stair which was found in place at the time the house was restored. It is old, except for certain parts, such as some of the balusters and the newel drop at the base of the first newel of the intermediate landing, which had to be replaced, and for necessary repairs which were made.

Both flights of the stair—from the first to the second floor and from the second floor to the attic—are of the U-shaped or "dog-leg" variety, with an intermediate platform between floors.

The first flight (first to second floor) begins with a run of 14 risers along the west wall of the stairhall, which is followed by a platform extending from wall to wall. The stair attains the second floor by means of a run of 7 risers along the east wall of the stairhall. From the second floor landing the stair continues to the attic with a straight run of 7 risers on the west wall, followed by a platform similar to the one below, from which four winders, making a 90° turn, lead to the attic.

The width of the three straight runs of the stair, measured from inside of string to inside of string, varies from 49¼" to 50¼". The two intermediate platforms are each approximately 52" in depth.

The stair treads of the first flight (first to record floor) average 11¼" in width, while the risers, which vary somewhat because of their worn condition, are approximately 6½ in height. The treads of the straight run of the attic flight are about 10½" wide and the risers 8½" high. A molding, consisting of a cyma and a bead, is applied to the top of the riser to cover the joint between the riser and the nosing of the tread.

41The stair railing has a molded handrail with turned balusters, three to a tread. The height of this railing, measured from the center of tread to the top of the rail, is, for the stair flight from the first to the second floor, 40", and for the flight from the second floor landing to the attic, 37¼". The newel posts are square in section and have caps whose profiles are similar to those of the handrail (see accompanying detail of newel cap). The initial newel post at the base of the stair rests on the floor of the hallway. This newel, more elaborate than the others, is paneled on three sides and beaded at the corners. The cap of this post is recalled on the paneled wall opposite as are the newel caps of the intermediate landing. The wall along which the stair rises is paneled from the first to the second floor, as was remarked before; the paneling starts at the corner of the west wall of the stairhall and runs to the second floor landing, where a plastered dado and chairrail are substituted for it. The spandrel 42 beneath the stair in the first floor hallway is also paneled. As was remarked earlier, the paneling is old, as are the various parts of the stair, except for baluster replacements and the replacement of the newel drop, which had disappeared. This newel drop is very similar to an old newel drop found on the main stairway of the Barraud House at the time of the latter's restoration.

MANTELS

There are six (wood) mantels in the Carter-Saunders House, several of which are he old mantels found in the house at the time of its restoration. The old mantels vary considerably from each other in design, which suggests that they were built at different periods. Four of the fireplaces are of the corner type and the remaining two—those of the southwest bedroom and study (library)--are built into the west side of the triangular mass of brickwork facing the corner fireplaces in the adjoining room. All of the fireplace openings have plastered surrounds with segmental arched heads. Most of the hearths are the old brick hearths found in place at the time of restoration.

Living Room Mantel

The mantel is an old one found in place. It is simple in its design with a molded architrave nearly square in shape, mitred at the corners and resting on rectangular plinth blocks. The architrave, 8½" in width, is composed of an outer quarter-round molding and two fascias, the inner of which is beaded on its inner edge. Above the architrave is an unbroken plane surface, somewhat less in height than the width of 43 the architrave. This is surmounted by a 2 1/8" molding supporting a shelf of slight projection. Applied to the wall on either side is a flat vertical strip against which the moldings of the mantel shelf and those of the chairrailing are returned. The considerable height of the fireplace opening (3'-8") suggests that the fireplace, and probably the mantel also are of a relatively early date.

Study (Library) Mantel

This is a new mantel, following very closely the design of the living room mantel. It differs from the latter in certain details only. The mantel shelf, for example, is heavier and has a greater projection than that of the living room and the plinth blocks at the base of the architrave are slanted inward rather than paralleling the face of the wall.

Dining Room Mantel

The dining room mantel has a molded architrave with crossettes or lateral projections at the head. Above this, applied flat to the wall 44 on either side, are S-shaped consoles or brackets in low relief, resting on small denticulated caps or sections of cornice. Between the consoles is a single rectangular raised panel, and above them, and appearing to receive its support from them, is a reduced version of a classic entablature, with architrave, pulvinated frieze and denticulated cornice. The latter, though much smaller in scale, recalls the denticulated main cornice of the room. The wall at the sides of the mantel and above it is sheathed with flush boarding, and the flanking walls of the projecting corner chimney are likewise partially sheathed.

This mantel is for the most part new and replaces a simpler mantel found in place which was thought to be late. When the architrave of this mantel was removed a section of raised paneling was found which formed the basis for the design of the rectangular panel used in the present mantel. Beside the raised panel was also found the trace of a portion of a scroll or bracket, which was thought to have been a part of the original mantel. This trace was followed in reproducing the scrolls of the new mantel. The entablature forming the top-most feature of the mantel was found in place and retained as part of the new mantel. The mantel in its present form is a combination of elements representative of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Northwest Bedroom Mantel

This mantel is the old one found in place in this room. Few repairs were necessary. The mantel, like the dining room mantel below it, is built in the diagonal face of the three-sided wall forming the corner chimney. It has an architrave with crossettes similar to the 45 architrave of the dining room mantel. It further resembles the latter in having above this an elongated raised panel, but the flanking consoles are absent. The denticulated shelf moldings closely resemble the top moldings of the dining room mantel but the frieze and architrave have been omitted. Above the shelf is a square raised panel, lining up with the rectangular panel beneath. The side faces of the fireplace wall are likewise panelled. A cabinet with a panelled door occupies the lower part of the right flanking wall.

Southeast Bedroom Mantel

This is the only one of the six mantels of the house without an architrave. It has instead paneled pilasters at either side, which "support" a somewhat heavy appearing entablature. This entablature is broken above the pilasters and at the center of the mantel to form candle shelves at either end and a clock shelf at the center. These features and the pilasters suggest that the mantel derives from the period from 1800 to 1810.

The wall above the mantel shelf is faced with sunken panelling, consisting of a row of four approximately square panels with a series of three elongated vertical panels above it. The flanking walls are also panelled.

The mantel is an old one found in place. The only alteration made was the removal of a molding which originally surrounded the plastered brickwork of the fireplace opening. The elimination of this molding is rather remarkable inasmuch as mantels of this type generally have them.

Southwest Bedroom Mantel

This mantel, the simplest in design of the six mantels in the house, is new, and is a replacement of a somewhat similar mantel found in place in this room. It consists of a double-molded architrave, without crossettes and plinth blocks, supporting a thin, shallow, unmolded shelf with rounded ends. The profile of the architrave is similar to that of the old window and door frames found in the same room and the shelf is patterned after which capped the mantel which was removed.

ARCHWAY

This archway, which enframes the opening leading from the front to the rear hall, is an old feature which was retained when the house was restored. The single alteration made was the substitution of a new five-fluted key block for the one found in place. Double-molded trim enframes the sides or piers of the archway and continues around the semi-circular arch. The piers rest on plinth blocks and are capped by flat imposts from which the arch springs. The trim of the archway, oddly enough, appears somewhat wider than that of the piers and the wedge-shaped key block seems small for the heavy-appearing arch.

Footnotes

The original Carter-Saunders roof (see sketch on following page) was of the M type, but it consisted of three A's set together rather than two, so that two parallel gutters resulted. These may at one time have discharged their water into a leader carried down through one of the chimneys or walls to a drain which conducted it away from the house. It is also possible that the subterranean vault which was found at the north side of the house was at one time a cistern used for the storage of the water collected on the roof and that the water was lead to this although, since the vault is considered by Herbert Ragland, who conducted the excavations, to have been of the fourth period of construction, it is likely that the roof had been altered to the two-sloped gable type by the time the vault was constructed.

Carter-Saunders roof truss, with valleys of earlier roof

Carter-Saunders roof truss, with valleys of earlier roof

Knight furthermore discovered no foundations directly south of the house in the position of the square building shown on the Frenchman's map. He states that the cross-shaped foundations directly south of the main house were those of low walls bordering paved walks and not foundations of a southern extension of the main building.

North facade of house showing "veneer" brick wall partially removed, exposing old weatherboarding (see next page).

North facade of house showing "veneer" brick wall partially removed, exposing old weatherboarding (see next page).

Acquia stone is crystalline in structure and has a dull whitish tan color. In some parts of the quarry there are intrusions of a pale reddish brown.

CONSTRUCTION DATES

The dates of the beginning and completion of restoration (or reconstruction) of the Carter-Saunders House and outbuildings are as follows:

| Started | Completed | |

|---|---|---|

| Carter-Saunders House | 7/7/1931 | 2/4/1932 |

| Carter-Saunders Garage-Addition | 11/21/1932 | 1/24/1933 |

| Carter-Saunders Guesthouse-Kitchen | 6/16/1931 | 2/4/1932 |

| Carter-Saunders Poultry House | 4/6/1936 | 6/10/1936 |

| Carter-Saunders Toolhouse-Privy | 8/19/1931 | 2/3/1932 |

| Carter-Saunders Wellhead | 4/6/1936 | 6/19/1936 |

| Carter-Saunders Woodshed | 1/29/1934 | 4/17/1934 |

CARTER-SAUNDERS HOUSE, BLOCK 30

CARTER-SAUNDERS HOUSE, BLOCK 30

CARTER-SAUNDERS HOUSE, BLOCK 30

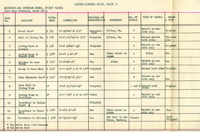

EXTERIOR AND INTERIOR DOORS, (FIRST FLOOR)

(See Door Schedule, Sheet #100)

CARTER-SAUNDERS HOUSE

| ROOM | FEATURE | COLOR NO. | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living Room | Walls & Ceiling | 223 | Warm ochre, light. Flat finish |

| Woodwork | 222 | Warm grey, light. Satin finish | |

| Library | Walls & Ceiling | 223 | Warm ochre, light. Flat finish |

| Woodwork | 222 | Warm grey, light. Satin finish | |

| Dining Room | Walls | 22 | Off white with touch of umber. Flat finish. |

| Ceiling | 227 | Off white, slightly greyed. Flat finish. | |

| Woodwork | 225 | Grey warmed with Siena. Satin finish. | |

| Doors | 226 | Off black with touch of brown. Varnish. | |

| Halls, Passage | Walls & Ceiling | 223 | Warm ochre, light. Flat fin. |

| Stairway to Attic & Pantry | Woodwork | 224 | Blue grey. Satin fin. |

| Powder Room | Walls & Ceiling | 223 | Warm ochre, light. Flat fin. |

| Woodwork | 222 | Warm grey, light. Satin fin. | |

| Kitchen | Walls & Ceiling | 223 | Warm ochre, light. Flat fin. |

| Walls | 223 | Warm ochre, light. Flat fin. | |

| Southeast Bed Rm. | Ceiling | 227 | Off white, slightly greyed. Flat fin. |

| Woodwork | 232 | Light tan with touch of umber. Satin fin. | |

| Fireplace facing | 142 | White with flesh tone. Satin finish varnish | |

| Doors | 226 | Off black with touch of brown. Varnish. | |

| Southwest Bed Rm. | Walls & Ceiling | 223 | Warm ochre, light. Flat fin. |

| Woodwork | 228 | Grey green. Satin fin. | |

| Fireplace facing | 142 | White with flesh tone. Satin fin. varnish. | |

| Northwest Bed Rm. | Walls & Ceiling | 223 | Warm ochre, light. Flat fin. |

| Woodwork | 232 | Light tan with touch of umber. Satin fin. | |

| Fireplace facing | 142 | White with flesh tone | |

| Passage outside | Walls & Ceilings | 223 | Warm ochre, light. Flat fin. |

| Southwest Bed Rm. | Woodwork | 228 | Grey green. Satin Fin. |

| Bathrooms | Walls | 230 | Pale tint of grey green. Satin fin. varnish. |

| Woodwork | 229 | Grey green. |

| Feature | Color No. | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Exterior doors, blinds, | 231 | Dark green |

| basement frames | black | |

| Porch floors | 468 | Dark grey, warm. |

| Exterior weatherboarding & trim | 696 | Off white with touch of yellow |

Carter-Saunders House - Architectural Report

Addenda to Paint Color Record

The interior paint schedule conformed to colors found on original wood work in the building.

The colors matching original colors are as follows:

| Pres. No. | Orig. No. | Room Found In | Used In | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 222 | 113-S | Hall | Living Room | Warm Gray |

| 113-S | Library | Warm Gray | ||

| 113-S | Powder Room | Warm Gray | ||

| 114-S | Halls #1, 5 & 6 | Gray | ||

| 114-S | Kitchen & Pantry | |||

| 225 | 115-S | Dining Room | Dining Room | Gray-Warm |

| 116-S | N.E. Bed Room | Not Used | ||

| 222 | 117-S | Library | 113-S used | |

| 223 | 118-S | Hall | 114-S used | |

| No Number | D.R. Doors | B. R. #7 Dining Room | Dark Umber | |

| 228 | No Number | Bed Room #8 | B. R. #8 | Green |

Information for PS & S file on Dinwiddie House (Archives) subject to check at the building and Paint Shop.

Orin M. Bullock

September 23, 1954

SUMMARY OF LOT AND HOUSE HISTORY

(Condensed from Research Report by Mary E. McWilliams, May, 1945.)

1746

ALTHOUGH it would seem that the location of the Palace near these lots in 1705 would have made them desirable at a very early date, the first known record of lots 333-336 is one of 1746. In March of that year Charles Carter, son of Robert, "King" Carter, sold the four lots, which already had buildings built upon them, to Robert Cary, a merchant of London.

1747

IN OCTOBER of this year Cary sold the property to Dr. Kenneth McKenzie, a physician of Williamsburg.

1747-1751

DR. MC KENZIE apparently lived here from 1747 through most of 1751. There is some evidence that he built or set up a shop on these lots and undoubted proof that he built a meat house which encroached upon the property of his neighbor on the south. The shop was probably used as a storehouse from which drugs and sundry articles were sold.

1751

IN 1751 the Council was forced to find a suitable residence for the incoming lieutenant-governor, Robert Dinwiddie, because of the "Ruinous Condition" of the Palace. It appointed John Blair and Philip Ludwell as a committee to rent a house for the governor. Dr. McKenzie's house was 53 finally purchased rather than rented. The deed of purchase covers "all that houses and four lots of land situate in Palace Street in the said city of Williamsburg and described in the plan of the said city by the numbers 333, 334, 335, 336 ... and all the buildings, houses and outhouses (except one House thereon being to wit the shop of ... Kenneth McKenzie which he ... is to remove off the Premises within six months from the date of these presents) together with the Yards, Gardens, Ways, Water Courses, etc...."

1753-

1761

ON DECEMBER 19, 1753 lots 333-336 were sold by order of Governor Dinwiddie to Robert Carter Nicholas, who owned and probably occupied them from 1753 to 1761. The evidence that Nicholas lived on these lots is a statement made by Robert Carter in a letter to the effect that Nicholas had built a stable and line of palings between this property and the lots to the south.

1761

IN MAY, 1761 Robert Carter of Nomini Hall purchased the four lots and came with his family to live in the house in March of that year. Carter was a member of the Council by 1762 and as such also a judge in the General Court of Colonial Virginia. He was a very important person, socially and officially, in Williamsburg, George Washington and Lord Botetourt dined at this house in 1769

1771-

1774

IN 1771, 1772, 1773, and 1774 Williamsburg carpenters, Ben Powell and Humphrey Harwood, repaired houses for Robert Carter. Their bills are included in the Appendix of the 54 Research Report. There is no proof as to the location of the houses but some of the bills undoubtedly refer to the buildings on Lots 333-336.

Among the items listed in these bills are the following:

"To building an Addition to Yr Studdy £ 8:0:0" "To pant and oil for priming the Side of Yr addition and pantry 7:6" "To Sundries of work by Mr Lamb About Yr orgin 5:0" "To 22 bushs lime a 9d & underping Closset 12/6 1:9:0" "To putting uppr. Steps & Jam to do 10/ 0:10:0" "To Fixing Back to Grate 2/6 & 3 days labr a 2/ 0:8:6" "To Mendg landary back & Jams & fixing backs 3/9 0:3:9" "To Ditto Kitching 3/9 & plastering oven 6d 0:4:3" "To Ditto well 1/3 & 1½ Days labr at 2/ 0:3:9" "To Repearing paling Round yr Garden and Yard Stoping up Gateway .&c 1:0:0" "To Repearg Charatt House & Stable 0:10:0" "To 100 Garden pales & 7 Garden Pales 0:12:9" "To painting your Gate and post 0:4:0" "To puting in 13 pains Glass 0:8:0"

1772

IN THE FIRST part of the year, 1772, Carter moved with his family back to Nomini Hall in Westmoreland County. The Carters did not immediately move all their belongings to Nomini; over a period of years they transferred an organ, wines, books, linens, and some furniture from Williamsburg to their plantation. In a letter to his agent, Jacob Bruce of Williamsburg, in the summer of 1772, Carter ordered "an 55 Inventory of all the goods in the Store room and other places, furniture & liquors in the House, specifying what liquor is in Casks, what in Stone Juggs, Car boys & Bottles ..." Among the articles which he requested be sent to him at Nomini is "The large Candle mould in the Closett in the Cover'd Way."

1774

IN A LETTER (Dec. 5, 1774) to his agent Robert Prentis, Carter lists among the articles which he left in the house:

"1 Saten Case, small containg a Camera Obscura, is in a Closet adjoining the Room called my Study ... All the Mortice Locks & Ectera belonging thereto, Do Closet Stone Jugs, containing Wine, in one of the Cellars ..."

1774

IN THE FOLLOWING advertisement in the Virginia Gazette of May 26, 1774, Carter offers to sell his house:

"THE improved SQUARE of LOTS adjoining the lots belonging to Mr. E. DEANE, coachmaker in Palace street, Williamsburg ...."

1775

CARTER FAILED to find a purchaser and in 1775 wrote to Mrs. Nelson of Yorktown, asking her to take possession of his house in Williamsburg. He told her that "Very lately some Workmen were in that House who were making repairs, then, in the Chamber & the passage above Stairs."

1776-

1780

IN THE SPRING of 1776, Dudley Digges, a member of the Council, took up residence in the house and was still there in October, 1780.

1783

THE REVEREND William Bland, who occupied Carter's house in the summer of 1783, stated in a letter to Carter that there was no garden on the lots and that the stables were being used by Joseph Prentis.

1783-

1847

THIS PROPERTY was in undoubted possession of the Saunders family from 1783 to 1847. There are facts to indicate that Carter's property passed to Robert Saunders, Sr. as early as 1801.

On all the variations of Williamsburg maps (the Unknown Draftsman's, the Galt, the Tyler, the Bucktrout, the Bucktrout-lively), the name "Saunders" is found in lots 333, 334, 335, and 336. The family of Robert Saunders, Sr. lived on lots lots 165, 166 & 172 near the St. George Tuckers on the east side of the Palace Green. It is not certain, therefore, although it is likely, that the following items in his will of March 30, 1834, refer to lots 333-336. He left several pieces of furniture to friends, viz. "a mohogany Desk and book case attached to it" in his dining room; "the cloathes Press long used by me, and in a corner of the Passage on the second floor near my bedroom -- also a mahogany Shaving box now used by me ..."

Saunders bequeathed all of his real estate to his son, Robert, whom he called upon to build a strong brick wall around the spot in the southwest part of the garden where his "best loved friends" were buried and where he, too, wished "to be entombed."

1835-1838

IT IS NOT recorded when various architectural changes, such as the addition of the columned front porch,* were made to the house but an increase in value of $1000, noted in the 57 tax records, to lots 333-336 and the houses on them may be significant. It is also uncertain when the Deane lots, #329-332, were added to the Saunders holdings. It is possible this had taken place by 1806 since in an insurance policy taken out in that year on the property now called the "George Wythe", Henry Skipwith gave as his boundaries the "Lott of Robert Saunders and the Church Yard."

1847

IN 1847, while serving as president of the College of William and Mary, the younger Saunders deeded to Edmund Christian, trustee for the College "that Certain & Well Known house & lot his residence situate in the City of Wmsburg & bounded on the South by Prince George Street, North by Scotland Street, East by Palace Green & west by the lot of Ro: H. Armistead." It is clear from this description of the boundaries of his property that Saunders now owned the Deane lots. Although the deed was made in 1847, the college authorities did not complete their title to the Saunders lots until 1872.

1862-1865

UPON THE MARCH of McClellan up the peninsula, the Saunders family left Williamsburg and the house was plundered of its invaluable historical records by members of the Union Army. David Cronin, Union Provost Marshal of Williamsburg, described as follows the scene he witnessed: 58

"We found the interior of the Page Mansion* in a state of complete wreck, empty of furniture except in broken pieces: the walls stained by streams of rain falling through leaks in the decayed roof and the floors covered with litter indescrible [sic]; the former library in the most deplorable condition of disorder and revage [ravage?]. In heaps on every side, were spread half destroyed books, vellum bound volumnes, some of them with ornate toolings; letters and documents of all sorts, ragged files of precious colonial newspapers; torn folios of rare old engravings. With these were mingled the remains of shattered marble busts, fragments of ornamental book cases, window glass and plaster mixed with the mud from heavy boots of cavalrymen who seemed to have played football with everything of value in the place .... we found manuscript minutes of the secret sessions of Congress, covering forty or fifty pages, consisting of memoranda of a debate upon the adoption of the American flag .... A thick packet of letters were from Thomas Jefferson to Page, some dating from their college days .... The rain filtering through the roof was fast 59 destroying the already mildewed papers in the garret and library: and the following day the Captain sent to town an army wagon accompanied by infantrymen with shovels. The litter of the garret and library was conveyed to the Fort where a number of ladies belonging to the families of officers assisted in carefully looking over the miscellaneous mass discovering many more relics of value nearly all of which, I was afterwards informed, reached public historical collections as gifts." (David Edward Cronin, "The Vest Mansion, Its Historical and Romantic Associations as Confederate and Union Headquarters, 1862-1865," Chap. XXVIII, 219-223.)

In the restoration of this house, the Architectural Department found old papers and letters under the floor of the garret, and cloth and old papers around a door frame. A doctor's bill of 1778, a letter of John Page to his wife in 1796, scraps of colonial news papers, tickets for a lottery with Robert Saunders' name written upon them, may be seen in the Courthouse Museum.

When Robert Saunders, Jr. returned to Williamsburg after the Civil War, he probably found his house in fair condition despite the depredations wrought by the Union soldiers, for he wrote his daughter, Lilia, "I shall merely have such repairs done to the house as are absolutely necessary, & this is very little—and have it cleaned and whitewashed."

Two residents who recall the appearance of Williamsburg at the time of the Civil War, have given descriptions of the property on this lot. Mr. John S. Charles wrote: