Brush-Everard House Architectural Report, Block 29 Building 10Originally entitled: "Brush-Everard House. 1718. Williamsburg, Virginia. A Comparative Microscopical Paint and Color Analysis of the Interior and Color of the 18th Century Architectural Surface Coatings."

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1631

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1994

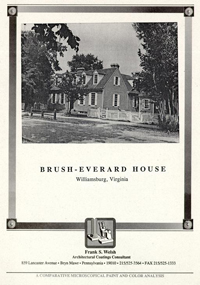

BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE

1718

Williamsburg, VirginiaA COMPARATIVE MICROSCOPICAL PAINT AND COLOR ANALYSIS

of the Interior and Exterior

to Determine the Nature and Color of the

18th Century Architectural Surface Coatings

Prepared for:

Department of Architectural Research

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Comparative Microscopical Paint and Color Analysis of the interior and exterior to Determine the Nature and Color of Original Architectural Surface Coatings

| Introduction | 1 |

| Sampling Methodology | 2 |

| Laboratory Methodology | 3 |

| Historical Overview | 6 |

| Decorative Overview | 7 |

| Summary of Finishes | 10 |

| Recommendations | 29 |

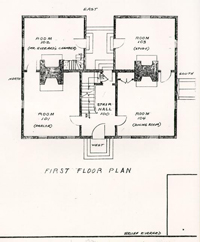

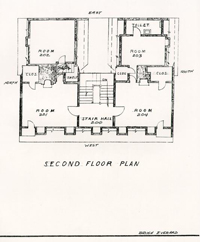

| APPENDIX A Floor Plans | |

| APPENDIX B Laboratory Data | |

| Cover Page | |

| Description of Presentation | |

| Abbreviation Key | |

| Data Sheets from Lab Analysis | |

| Photomicrographs | |

| APPENDIX C Paint Analysis Article by Frank S. Welsh | |

| APPENDIX D Contract Documents | |

| APPENDIX E Resume of Frank S. Welsh |

INTRODUCTION

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES OF THE PROJECT

Frank S. Welsh was retained by The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation as a consultant to identify the surface treatments of the Brush-Everard House, one of Williamsburg's earliest frame buildings. This report on the historic finishes follows an investigative process begun in March, 1991, in which all representative painted surfaces and features were sampled and analyzed.

The spaces to be investigated and sampled and the scope of the project were determined by the Department of Architectural Research. Included were all old exterior and interior features of the building. The plaster was not included since it was completely replaced in the late 1940's restoration.

The objective was to identify the composition and color of the 18th century coatings on every surface, including any decorative painting that might have existed. Specifically, the scope of the investigation was to investigate, microscopically analyze, and evaluate the nature and color of the original and second major period finishes and to list the later layers by general color name only.

The field investigation, sampling of surface materials and microscopical analysis was performed by Frank S. Welsh to determine the color, type, gloss and kind of the architectural surface coatings of primary interest. Approximately 190 samples were gathered throughout the house for analysis and they are retained in the office of Frank S. Welsh.

To simplify the reading of this report, the results are presented in a room-by-room narrative summary form with illustrations and color chips. Also on a room-by-room basis, the data from the lab analysis is written out on the sample envelopes which follow in Appendix B. This laboratory data section should be thoroughly examined because it attempts to answer the numerous questions posed concerning the many architectural alterations which took place in the 18th century. Several photomicrographs of the paint samples are included in this Appendix B. The floor plans, contract documents and resume of Frank S. Welsh are also included in the Appendices.

SAMPLING METHODOLOGY

The physical research that precedes any historic restoration project is a process of making, testing, remaking, and retesting a series of hypotheses about the building's original condition. This is as true of a building form and its alterations as well as of paint and decorative finishes. This format guided the on-site work of paint sampling.

As a basis, the building and its form were studied, both from early photographs and from written explanations of the building all of which are presented in the 1950/52 "Architectural Report" by Lawrence Kocher and Howard Dearstyne. Several questions, however, remained unanswered: Could any known alterations be confirmed by the paint history of the wood trim? Was the building painted all at once or was a portion painted later? Were some of the original architectural elements reused during later alterations? How do the two samples of original wallpapers relate to the trim paint colors in the rooms where they were found?

The physical investigation and sampling of the finishes were conducted by Frank S. Welsh. Sampling for any paint research project includes areas that are typical as well as those that are likely to vary from the norm. On large surfaces several samples are taken from locations that are widely separated. As the sampling progressed the building's original color scheme became obvious. Observing this, the samplers made a special effort to find the best evidence of color and any potential later variations. To reach the upper walls and cornices, step ladders were used. As samples were gathered, field notes were taken about the initial findings and conditions of the spaces. Room by room, surface by surface, molding by molding, the samples were gathered, ordered, and prepared for microscopical analysis, both on-site and in the lab.

LABORATORY METHODOLOGY.

The tools and equipment used for this analysis included a stereo-zoom microscope (10-105 X), a polarized light microscope, a surgical scalpel, a variety of reagents, and the Munsell Color Books. The small representative samples that were taken for analysis and color matching are retained by the office of Frank S. Welsh. Color matching was done with natural (sky) light and also with a halogen light source at 3200 K. We are aware that architectural paints tend to fade in color with age; therefore, during the investigation we attempted to find the cleanest and brightest samples possible for use in color matching. Where we could not find the best color samples, we estimated a color slightly lighter and brighter to compensate for yellowing of oil mediums and darkening of pigments because of age.

In this report the evaluation of findings is presented on a room-by room basis in two sections. The Summary of Finishes section is first and presents the conclusions from the laboratory analysis. It is illustrated with the Munsell color chips. The Laboratory Data section is in Appendix B and presents layer by layer descriptions for each sample taken and analyzed. This section is extremely significant because it attests to the extensive alterations which took place, and therefore, the Laboratory Data should be thoroughly reviewed. The results of any pigment analyses using the polarized light microscope will be included at the end of the Laboratory Data section and marked: PLM.

The conclusions are based on the evidence obtained by investigating as many "test areas" as is feasible. This type of investigation is somewhat analogous to "archaeology above ground." Certain limitations are implicit because the research does not constitute or signify a complete "excavation." We caution against holding these conclusions as absolute--the possibility of human error always exists.

The colors of the original paint films are named according to the National Bureau of Standards Color Name Charts and matched to the Munsell Color System. These color names and notations are used as a means to describe color in a standard and universal manner. The Munsell Color System "identifies color in terms of three attributes: hue, value, and chroma." The Munsell Color Company, which is not a paint company, is presently located in Newburgh, New York.

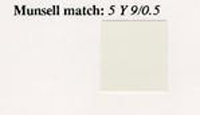

Estimated Munsell color notations are identified parenthetically within the report; for example, (5 Y 9/0.5). The Munsell color standards between which the visually estimated notation falls are not listed in the analysis section. Rather, this information is in the summary section for each room.

The commentary which will follow this introduction will include a brief summary of the early relevant historical and documentary information currently available. It also includes some general conclusions drawn from the paint analysis and some remarks concerning the paints and finishes used in the Brush-Everard House relative to those used in other architecture of the same period.

This report may be used to assist in the preparation of a restoration paint color schedule for the restoration/preservation of these 18th century finishes. It may also serve as a source for gaining a greater understanding of regional and period architectural decorative styles. I hope that the report presents the reader with a concise picture of the paint history and finishes of the building.

If new evidence of any kind is discovered that would amplify and/or change these findings and conclusions, I request immediate notification for the purpose of further evaluation and discussion.

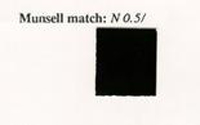

-4- DESCRIPTION OF MUNSELL COLOR SYSTEM

DESCRIPTION OF MUNSELL COLOR SYSTEM

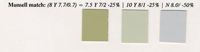

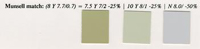

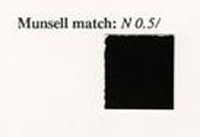

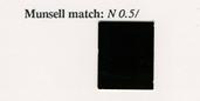

ESTIMATED MUNSELL NOTATIONS

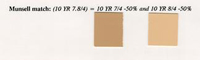

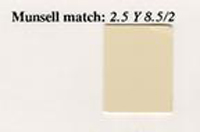

In the Summaries of Original Finishes and in the Laboratory Data, when a set of parenthesis surrounds a Munsell Color notation (Hue Value/Chroma) it is being designated as an estimated notation. This means that the original color of the paint film does not match exactly one of the regularly produced (stock) color standards (samples) in the Munsell Color System. The estimated notation in parenthesis (H V/C) falls somewhere in between the closest regularly produced (stock) color standards. These small "chip" size standards are those which are attached in the Summary of Finishes section. The estimated notation can be specially produced by Munsell if required.

Each of these standards is accompanied by a percentage that indicates the relative amount of that standard color contained in the estimated color. This will also help in matching a paint to the estimated color.

EXAMPLE: In the Summary of Finishes section, an original color might be matched to an estimated Munsell color notation and would appear like this:

Munsell match: (5 Y 7/5) 5 Y 7/4 -50% and 5 Y 7/6-50%The (5 Y 7/5) is an estimated notation and is designated by the parentheses. The closest "stock" notations are the ones which follow the equals (=) sign. In this example, the original color of the paint was (5 Y 7/5) and is midway between the two color chips, hence the 50 % after each color chip's notation. Order from Munsell Color Company the samples of the two color standards: 5 Y 7/4 and 5 Y 7/6. Mix 50% of the total quantity of paint needed to match the 5 Y 7/4 color standard and the other 50% needed to match the 5 Y 7/6 color standard. Combine the two (50%) mixes to obtain 100% of the estimated color: (5 Y 7/5).

Caution: Today's tint base paint color systems can present a problem. If one (lighter) color is mixed in a Pastel Base and the other (darker) color is mixed in a Medium Base, a 1:1 (50-50) combination of the two does not yield a color midway between the two mixes. This is because the Medium Base tinted color will absorb more color than the Pastel Base color. They have unequal tinting strengths. Consequently, it is essential to have your paint company formulate your paint color using the same tint base for each color that you will be combining to match the estimated Munsell color.

THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE-A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The Brush-Everard House was constructed in 1718 by John Brush who was the town's gun smith and first keeper of the Magazine on Market Square. The house is prominently located on the Palace Green across from the Governor's Palace. The second owner of the house was Elizabeth Russell who acquired it in 1727. William Dering was the third (principal) owner, purchasing it in 1742 from Henry and Elizabeth Cary. The fifth owner, Thomas Everard, bought the property in ca. 1751 and owned it until he died in 1781. Everard was twice mayor of Williamsburg, active as a court clerk and was on the vestry at Bruton Parish Church.

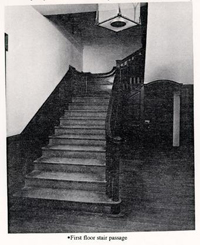

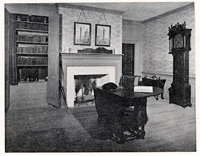

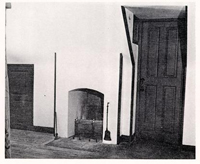

The Brush-Everard House is a 1 ½ story, single pile, frame structure, laid out on a central passage plan with a matching pair of rear ells. These appendages are connected by an enclosed rear porch which also opens to the front passage. The open string staircase in the passage rises to a middle landing and then returns to the second floor. On the upper floor, there are two original bedrooms remaining in the front (west) which have window seats and knee wall closets. There are two bedrooms in the rear over the appended ells; the north one being original. There is a private stairway connecting the northeast first and second floor rooms.

On the first floor the northwest room probably functioned as a parlor and the southwest room may have functioned as a dining room. Both rooms have added wainscot and chimney breast paneling. The south ell room (Study) is virtually a complete reconstruction by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, done in the 1940's. The north ell bedroom (Mr. Everard's chamber) is a combination of original doorway features to the front parlor and of added windows, cornice and mantel which probably date to the later years of the eighteenth century.

On the exterior, the restored clapboards duplicate the originals, most of which had been replaced prior to the restoration. The 9 over 6 window sashes are largely original as is the raised panel shutter on the north side of the southern most front window. The original roof was covered with clapboards instead of shingles and an original section of this is still in place.

Overall, the Brush House portrays the widespread shift from earth fast building to more permanent techniques of construction that occurred in Virginia during the first decades of the 18th century. This was a change that was tied to the changing social as well as agricultural and economic conditions in Virginia. If the staircase and associated trim are indeed original, as the paint analysis suggests, then it would be one of the earliest such detailed spaces in the Tidewater area. Moreover, the symmetry of its front elevation, together with its sliding sash and dormer windows, brought a stylish new look to the Virginia landscape.

THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE-A DECORATIVE OVERVIEW

The sampling of finished surfaces in the house has been examined with a degree of thoroughness and completeness befitting the architectural and historical stature of this colonial building.

One question was of particular interest:

Can the paint analysis, used as an architectural research tool, shed light on the age of various architectural elements, including the staircase and on the wainscot paneling in the first floor front rooms?

The answer to this question is not as complicated as originally anticipated. In the stair passage, virtually all features, except for several 19th and 20th century replacements of balusters, have identical layering sequences which suggests that all features are early and original. This assumption holds unless the trim in the house was not painted originally in 1718, or if the present interior is the product of an extensive remodeling. If either of these is the case, then paint analysis can not answer the question.

The paint analysis also found the necessary evidence to place a relative date on the installation of the wainscot paneling and other associated alterations in the front rooms. In addition, the later window trim, cornice and mantel alterations in Mr. Everard's chamber (Room 102) are more clearly datable now with the lab data.

From the beginning of this project, it was our intent to present in this report those finishes not only of the very first painting period, but also of the finishes dating to the major changes in trim in the first floor rooms. We have called these Period 1 and Period 2 and they are not to be confused with finish paint layer 1 and finish paint layer 2.

PERIOD 1: FIRST MAJOR PAINTING/CONSTRUCTION PERIOD

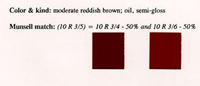

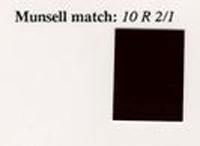

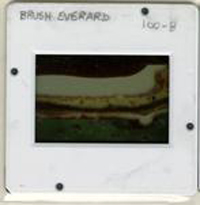

Overall, the findings show the earliest woodwork was originally painted in a manner very much in keeping with the fashion of the day for the region. All of the earliest 18th century wood trim was first finish painted with a moderate reddish brown, red iron oxide, oil paint. There do not appear to be any exceptions to this finding. The plaster treatment of course is unknown because it all was replaced in the 1940's restoration.

Years after this early uniform finish painting of the trim, each room was repainted at a different time and usually in different colors which is a surprising contrast to the original owners conception of one color throughout. For example...

PERIOD 2: SECOND MAJOR PAINTING/CONSTRUCTION PERIOD

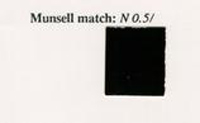

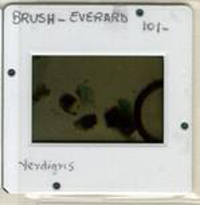

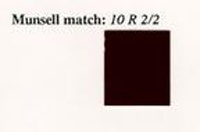

A light gray and a white were used in the second floor rooms; the same light gray was used in the entire stair passage and in Mr. Everard's chamber (Room 102); whereas, a bright verdigris green was used in the Parlor (Room 101), while a dark brown was used in the Dining Room (Room 104).

When the alterations were undertaken in the front rooms, a similar but darker shade of green was used on the trim in the Parlor (Room 101), and across the passage, the Dining Room (Room 104) was painted with a yellowish white which is probably the contemporary trim paint for the yellow wallpaper fragment found during the 1940's restoration. -8-

The trim in Mr. Everard's chamber, which had already been repainted several times, was all painted with a pale yellow ocher color when the windows, cornice and mantel were installed in the later 18th century and presumably was painted that yellow when the blue wallpaper (salvaged during restoration) was applied.The baseboards were painted with blacks and browns in the later periods--after the original red oxide--but these dark base colors were typically not painted across the doors and door trim as was so frequently done in the period. The one exception here is the Dining Room (Room 104).

All of the 18th century paints are oil based--probably linseed. The red iron oxides, the blacks, and the darkest browns are all dispersed in the oil and no white lead was added to them. The dark green (verdigris and varnish) glazes used in the Parlor (Room 101) likewise did not have any white lead added. The other colors described below in the summaries of the mid 18th century paints all have white lead as a base which is ground in the oil and tinted with the coloring pigments. These lead based paints all generally had a slight surface texture called ropiness. The characteristic brush marks were created by laying off the paint with the bristle brush. The oil paint did not flow out like a modem enamel. Consequently, the brush marks were retained in the paint film after it dried.

Also, for purposes of simplification in the report, I have labeled the earliest interior woodwork finishes as first period or period A, the next major period is the second period or period B. You will see the first and second period designations mostly in the summary of finishes sections and the A and B designations in the laboratory data section under the column marked "P" on the handwritten envelopes. There are sometimes paint layers in between these Period designations but they fall between the major construsction periods which we are attempting to emphasize in this effort.

SUMMARY OF ORIGINAL FINISHES

EXTERIOR

The exterior of the house retains many original features but only one piece of painted original wood trim seemed to be a good candidate for finding original paints. It is the North shutter on the southwest window. Although the old photographs show that it was protected for a long time by a front porch, the elements had long since weathered off the early paint finishes. I sampled its front and back in the cracks and crevices and found nothing old. This means that we will know nothing about the exterior colors of the Brush-Everard house. Until further investigations are undertaken on other period buildings of the same construction type which retain original fabric and paints, I can not even speculate on the early and mid l8th century paint colors which might be appropriate here.

SUMMARY OF FIRST PERIOD FINISHES

INTERIOR -- ALL ROOMS

All of the earliest trim in the house was painted initially with two coats of a moderate reddish brown, oil, semi-gloss paint. The pigment used was red iron oxide also known as red ocher. It was a very commonly used pigment and a very typical paint color in the early to mid 18th century. We have seen the same used in the many public buildings that we surveyed for the paint study used for the Court House restoration. We also found it on the Ludwell-Paradise House exterior cornice.

During the microscopical analysis I was constantly looking for any hint of dirt on the wood surface underneath the first layer of paint which would suggest a period of time when the wood was exposed and not painted after construction was completed. I was unable to find any evidence of this nature. Therefore, I can only report that it appears to me that this red oxide paint must date to the installation of the earliest woodwork.

If this is indeed true, then all of the features of the staircase, except for obvious replacements, are from the same early period because they all have the red iron oxide paint on them. Also, the paint layering on all features (except the baseboards) is identical.

-13-SUMMARY OF SECOND PERIOD FINISHES

ROOMS 100 AND 200 -- THE STAIR PASSAGE

When the stair hall was repainted for the first time, a light gray color was used along with black on the baseboards and stair skirting. There is enough dirt on the original moderate reddish brown to suggest that it was not repainted for a long time. The amount of dirt on the light gray is average which suggests that it lasted for 15 to 25 years. The next layer above the gray is a light brown for which there is fairly good evidence on the first floor and staircase but poor evidence on the second floor. This light brown also has a substantial amount of grime on its surface which suggests that it too was not painted over for many years. My guess at this time based on comparison of the evidence in this room and iff the other rooms is that this light brown might be a ca. third quarter 18th century color which stayed exposed for much of the late 18th century. I believe that the light gray was probably a color contemporary with the mid 18th century, even if it remained after a change of owner.

-15-Feature:

Wood trim: baseboards and stair skirt (stair baseboard)

Wood trim: baseboards and stair skirt (stair baseboard)

SUMMARY OF SECOND PERIOD FINISHES

ROOM 101-PARLOR

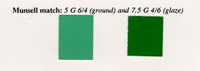

This parlor was repainted for the first and second times with the same medium green paint color and glaze. The green pigment in each is verdigris. These finish colors are not summarized here.

Later, in the Second Period, when the wainscot, chimney breast paneling and mantelpiece were installed, the room was again painted in the same green color with paint of the same composition; however, the top varnish glazing coats on the green paint were very heavily tinted with verdigris which altered the overall effect of the color. For this period there is the base medium green made with white lead and verdigris followed by two coats of a darker green glaze. The evidence shows that the baseboards were painted a dark brown at this time but it was not carried across the base height of the doors and door trim.

-17-SUMMARY OF SECOND PERIOD FINISHES

ROOM 102 -- MR. EVARARD'S CHAMBER

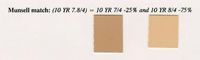

All of the features associated with the doorway to the Parlor are early and have the original red iron oxide paint on them. The second paint layer is the same light gray that is in the stair hall and in the southwest chamber. The third, fourth and fifth layers are gray, medium green and medium blue--typical 18th century colors. The 6th finish system is the medium green with dark green glaze (along with dark brown baseboard) found with the installation of the wainscoting in the adjoining front parlor. The next finish coat is a moderate orange yellow which is also the first finish coat on the (later) window trim, cornice and mantelpiece. The evidence suggests that the baseboards were black with this moderate orange yellow trim color. Also, this color scheme may well be the one which is contemporary with the blue wallpaper remnants found in the room in the 1940's, because the fragments appear to have been removed from the area above the window trim and below the cornice.

-19-SUMMARY OF SECOND PERIOD FINISHES

ROOM 103 -- STUDY

The paint evidence in this room is not very good; however, it appears that the original trim features and those which were added in a later remodeling were painted with a moderate orange yellow color along with black baseboards at this later, possibly second, period. Please read the lab data--samples 103-1 to 103-7 for the information related to these later alterations which become apparent by studying the paint layers.

-21-SUMMARY OF SECOND PERIOD FINISHES

ROOM 104 -- DINING ROOM

After the original moderate reddish brown, the Dining Room was repainted with a dark brown paint on all of the trim except the baseboards which were painted black. When the wainscot, mantelpiece and cornice, etc. were installed, the trim in the room was painted with a yellowish white and the baseboards, entire door and the base height of the door trim was painted dark brown. This is probably the contemporary trim color associated with the yellow wallpaper remnant found during the 1940's restoration because the fragments appear to have been removed from the area above the window trim and below the cornice.

-23-Feature:

Wood trim: baseboards; door; baseheight of the door trim

Wood trim: baseboards; door; baseheight of the door trim

SUMMARY OF SECOND PERIOD FINISHES

ROOM 201 -- NORTHWEST CHAMBER

This chamber, like the passage, went for a long time with its original moderate reddish brown paint. When it was repainted for the first time, a white color was used on all of the trim along with black baseboards. This black was painted across the trim of the knee wall doors and trim but not across the larger room doors and their trimmed openings.

The rear passage between this front bedroom and the lumber room (Room 202) is one which represents many changes. It is a room whose paint history is not easily summarized and I will leave it as such and direct the reader to carefully read the laboratory data for this space. The same is true for the lumber room itself. See Laboratory Data for Rooms 201-A and 202.

Second floor front chamber

doorway to the rear stairs

Second floor front chamber

doorway to the rear stairs

Feature:

Wood trim: baseboards; baseheight of knee wall doors and their trim; baseheight of the dormer window panels

Wood trim: baseboards; baseheight of knee wall doors and their trim; baseheight of the dormer window panels

SUMMARY OF SECOND PERIOD FINISHES

ROOM 204 -- SOUTHWEST CHAMBER

The southwest chamber, like the passage, went for many years before being repainted. When it was, the same light gray from the hall was used along with the black baseboards. This light gray is the paint which appears to be the one which would have be on the trim in the second period. The paint layer above is a medium (Prussian) blue with a glaze. My suspicions are that this blue is a paint from the third quarter of the 18th century. The next few layers above the blue are more typically 19th century.

-27-Feature:

Wood trim: baseboards; baseheight of the dormer window panels; baseheight of the knee wall closet doors and trim

Wood trim: baseboards; baseheight of the dormer window panels; baseheight of the knee wall closet doors and trim

CONCLUSIONS

THE COLORS OF BUILDING -- AN INTERPRETATION

The decorative finishes analysis of the Brush-Everard House, has resulted in an interesting discovery not only of how the rooms' trim was painted originally and in later periods but also, and with equal importance, how the house evolved with the many major and minor alterations.

At the outset the goal was to determine how the house appeared when it was first painted and then how it appeared when the the major alterations in the first floor rooms were made. As the summaries of finishes describes and the appended laboratory data attests, the interpretation/dating of the remaining paint evidence is not that easy.

We see that the second floor bedrooms and stair hall were not painted very frequently in the early years after the installation of the present woodwork. Also, few alterations are apparent in these spaces when the earliest paint layers were being applied. If there were early alterations, then they were done either before the house was painted or they exactly matched the original red iron oxide paints, which, by the way would be an easy task since 18th century red iron oxide in this area is all the same color. My objection to this possible scenario is that I don't find any dirt surface variations to substantiate it.

When we compare the number of times the Parlor was repainted with the medium green to the infrequently repainted Dining Room, all before the installation of the paneling, we have to look at the materials. The green color, achieved with the very fugitive pigment verdigris, quickly changes color to a dirty brownish olive. If this northwest parlor was an important ant entertainment space, then the frequent repainting with the same paint color is more clearly understood.

The same type of comparison might be made of Mr. Everard's chamber adjoining the Parlor. Seeing the second finish light gray (the same as the second finish in the stair passage) and the subsequent gray, blue and greens above and comparing the layers to those in other rooms, there seems to be a suggestion that this was a very different if not very important room. The number of layers plus the later change (later than the wainscot installation in the front rooms) serves to confuse the dating hypotheses developed through the rest of the house.

As a final observation, I find the comparison remarkable between the original paint scheme of this early house which was so plain and simple--with one shade of moderate reddish brown used all over the trim--and the repainting color schemes (probably commencing with the first change of owners) where there is virtually a different color used in every room. And, my guess is that each room was basically repainted at a different time (except for the second finish light gray used in the stair passage, Mr. Everard's Chamber, and the Southwest Chamber. This finding presents challenges for my interpretation as well as for the eventual interpretation of the house. We might see some paint periods which overlap or are entirely separate from room to room.

In any case, the finishes and colors that this study has found are those which I consider to be very typical of the periods which are represented. They reflect the time, the place and the personal taste of the people who chose them. I think that the additional knowledge of the use of and the colors and patterns of the wallpapers in two of the rooms coupled now with the added knowledge of contemporary wood trim colors make the understanding and interpretation of the Brush-Everard House unique in Colonial Williamsburg.

RESTORATION RECOMMENDATIONS AND CAUTIONS

To portray an accurate restoration of the original finishes of the Brush-Everard House, we offer the following recommendations and cautions:

It has been a privilege to discover the history, finishes and colors of the Brush-Everard House and I look forward to a continuing role in the future repainting efforts.We recommend that the surfaces which originally were painted be repainted, carefully matching their original colors and gloss levels. The color schemes and finishes are very representative of the period and were probably planned and executed with great consideration and care.

All of the surface preparation and the paint application should follow carefully considered specifications. The longevity of the finished product depends upon careful preparation and material selection. Professional planning at this stage is of utmost importance.

Techniques for paint removal and surface cleaning must be carefully researched and tested in order to avoid irreparable damage. Consideration should be given to preserving the later paint layering in selected areas to facilitate future scholarly research.

This office would like to be represented in all decision making regarding the restoration of historic finishes. We are able to provide consulting services at any level of detail from recommendations for restoration treatment to the actual supply of all paint materials, accurately formulated to match the original colors, textures and finishes.

APPENDIX B

DESCRIPTION OF THE PRESENTATION OF THE LABORATORY DATA FROM THE ANALYSIS

The following pages contain photocopies of compilations of sample envelopes upon which I have written all of the requisite information during the laboratory analysis about the coatings found on each sample. There are no more than 12 sample envelopes per page and each page contains only samples from one room.

The information on these pages is the data from which I have drawn my conclusions which are presented in the Summa[y of Finishes section. The reader who is interested in the minute detail of findings on each sample taken from the building can refer to these data sheets.

To fit so much information onto the small sample envelopes, I have developed a system of abbreviations to describe the samples and the historic coatings. The following page is the KEY to these abbreviations.

KEY TO THE ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE LABORATORY DATA SHEETS

| Bldg = | building name |

| Smp# = | room number - sample number |

| Sample Loc: = | location where the sample was taken |

| L = | layer of the coating, ie. 1, 2, 3 |

| C = | color name, ie. blue, white |

| M = | Munsell color notation, ie. 5 Y 9/1 |

| T;G = | type of paint, ie. oil, whitewash, and gloss of the finish, ie. flat, semi-gloss |

| P = | the period of the layer which is an arbitrary designation of A, B, or C, depending upon the project. The first letter (A) could symbolize the first finish paint period and the second letter (B) could symbolize the second painting period of the space, and so forth. This is simply a system to help organize complex decorative finish schemes from sample to sample. |

| A = | the age of the coating, ie. original or late 19th century |

| For layers: | |

|---|---|

| P = | prime coat |

| I = | intermediate coat |

| Gr = | ground coat, ie. for marbling or graining |

| F = | finish coat |

| For colors: | |

| W = | White |

| YW = | Yellowish White |

| YG = | Yellowish Gray |

| MRB = | Moderate Reddish Brown |

| MOY = | Moderate Orange Yellow |

| POY = | Pale Orange Yellow |

| For type of paint: | |

| 0 = | oil |

| D = | distemper or calcimine (a water base paint) |

| Wsh = | whitewash |

| Pb = | lead paint |

| Zn = | zinc oxide paint |

| For gloss of the finish: | |

| FI = | flat finish |

| L = | low-gloss finish |

| S = | semi-gloss finish |

| G = | gloss finish |

| H = | high gloss finish |

| For the age of the layer: | |

| orig. = | original |

| er = | early |

| md = | middle |

| lt = | late |

| c = | century |

LABORATORY DATA FOR PAINT SAMPLES

APPENDIX C

PAINT ANALYSIS ARTICLE

BY FRANK S. WELSH

29

APT Vol. XIV No. 4 1982

PAINT ANALYSIS

Frank S. Welsh*

The investigation of historic architectural paints and coatings is more commonly called a paint analysis. It is a specialized form of research which uses a variety of microscopic and occasional chemical and ultra-violet bleaching techniques to analyze, determine and evaluate the nature and original color of historical surface coatings on wood, plaster, metal and masonry. The information that this often very time consuming investigation seeks to determine concerns:

- Numbers of layers of coatings (including prime and finish coats)

- Original colors (recorded in notations of the Munsell Color System)1

- Distribution of colors and coatings

- Decorative painting (i.e. graining, marbling, stencilling etc.)

- Types of coatings (i.e. oil or water base paints/stains/ glazes/varnishes or wallpapers)

- Physical characteristics (i.e. gloss and texture)

- Approximate date or period of each layer

In the process of compiling and evaluating this data for each area of a building, if there have been any later architectural changes which were not readily apparent, they can be determined by carefully comparing differences in numbers of layers of coatings with those on original features. Through this comparative analysis, the approximate date of the changes can be calculated. In this light, the paint analysis performed by a specialist2 can be an invaluable tool to the architect, or others, who may be preparing a Historic Structure Report. Both Investigative efforts should be undertaken in conjunction with each other in order to coordinate findings and conclusions and eliminate possible contradictions. The best time for the paint analysis to begin is after all historical (documentary) research3 is complete and the structure has been measured and drawn. Experience has shown that it must be considered absolutely essential to have the analysis performed on the entire building at one time because when any areas are studied in isolation or out of context with the whole, the benefits of comparing layering sequences and colors found on similar features in different areas (and picking up on possibly overlooked or misinterpreted information) are forsaken. The potential for arriving at erroneous conclusions is substantial if the analysis is not done in this comprehensive way. A very important responsibility of the architect or administrator is to provide the paint specialist with as much information on the structure as possible - working with and questioning the preliminary findings closely in order to bring out all of the subtle nuances in the building that are presently known or can be discovered.

A microscope must be used for a paint analysis because many surface coatings (especially 18th century paints) are too thin or degraded to be discerned by the naked eye or even with a handheld magnifier (5X to 8X). An inexpensive binocular microscope (15X to 30X) is usually taken along for the on-site investigation so all of the many samples removed for analysis can be examined immediately to determine whether or not they have good paint evidence on them. This helps to keep transportation costs low by reducing or eliminating the need for return trips. The complete micro-analysis with a high quality binocular stereo zoom microscope (10X to 70X) is done back in the laboratory.4 There the extracted samples can be carefully examined for recording all of the information that can be found on them in relationship to the seven catagories listed above.

Distance, time or financial constraints may sometimes make an on-site investigation by a consultant impossible. In such a case, paint samples can be taken by others and forwarded to the consultant for analysis. However, it must be realized that the samples sent may not be truly representative. They might be missing some paint layers, be a poor sample for matching the original color, or as can happen frequently, have no original paint evidence left on them at all. Because of this, the results - naturally - can only be as good as the samples themselves. Many times, new samples must be taken.

30It is the responsibility of the consulting paint specialist to take all of the technical data gathered in the paint analysis and present it in a concise format which can be readily understood by the architect or administrator client.5 Documentary support such as color photomicrographs taken of important samples and small "chip"6 size Munsell color standards of the recommended restoration period colors can be included in the final report along with recommendations about paint removal, methods for conservation and preservation of original finishes and types of paint for restoration repainting.

The comparative microscopic paint and color analysis is an essential part of the investigation of a historic building. The concluding report and its recommendations provide a significant part of the documentation required for a complete Historic Structure Report.

Footnotes

Bibliography

The Association for Preservation Technology has published 18 articles or supplements since 1969 on the subject of architectual paints and their analysis. They are listed here and can be obtained from the Executive Director in Ottawa, Ontario, or at any library which is a member of APT.

- "Paint Color Research, Painting Procedures"; Newsletter Vol. I, No. 2, 1969

- "Notes on Housepainting Practices"; "Dark Mopboard"; Bulletin Vol. I, No. 3, 1969

- "Notes on Linoleum and Paint Bulletin"; Vol. II, Nos. 1-2, 1970

- "Discoloration of Old House Paints"; Bulletin Vol. III, No. 4, 1971

- "Early Wall Stencil in Philadelphia"; "Stencilled Wall Designs"; Bulletin Vol. V, No. 2, 1973

- "Introduction of American Zinc Paint"; Bulletin Vol. VI, No. 2, 1974

- "Use of Paint In Early Ontario"; "Pennsylvania 18th C. Sponge Painting"; Bulletin Vol. VII, No. 2, 1975

- "Paint Research and Reproduction", Bulletin Vol. VII, No. 4, 1975

- "Methodology for Exposing Graining"; Bulletin Vol. VIII, No. 2, 1976

- "Zinc for l9th C. Paint and Architectural Use"; Bulletin Vol. VIII, No. 4, 1976

- "18th C. Copper Roof"; "Mid-19th C. Color Scheme"; Bulletin Vol. IX, No. 2, 1977

- "Techniques Employed at the North Atlantic Historic Preservation Center for the Sampling and Analysis of Historic Architectural Paints and Finishes"; Bulletin Vol. X, No. 2, 1978

- "Paints for Architectural Cast Iron"; Bulletin Vol. XI, No. 1, 1979

- "18th C. Black Window Glazing in Philadelphia"; Bulletin Vol. XII No. 2, 1980

- "Documentation of the 1902 Paint Colors of the Florida State Capitol"; Bulletin Vol. XII, No. 2, 1980

APT Bulletin

- "Paint Bibliography"; Communique Vol. IV, No. 1(s), 1975, now out of print; incorporated in the following Publication Supplement

Communique

- "Paint Color Research and Restoration of Historic Paint"; Publication Supplement; 1977

Publication Supplement

APPENDIX D

CONTRACT DOCUMENTS

The

Colonial Williamsburg

Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia 23187

Foundation Architect

Mr. Frank Welsh

Historic Paint Consultant

859 Lancaster Avenue

Bryn Mawr, PA 19010

Dear Frank:

This letter is to confirm our agreement regarding paint analysis of the Brush-Everard House during March 12-14, 1991. This will include analysis of the exterior and interior painted surfaces that still contain original eighteenth-century period paint finishes. our aim is to identify the first and second period finishes in order to better understand the evolution of the house as well as to replicate the paint finishes of the house during the period of its interpretation. We also want to know what color the woodwork was when the wallpaper was on the walls.

The report will follow the guidelines outlined during our paint symposium in November 1989, and shall be suitable for publishing in the book "Paint in America" if the Barra Foundation elects to do so.

As agreed, your fee will be ____ including expenses and I would be very pleased to have to stay with me while you are in Williamsburg. If this is agreeable with you, please sign both copies and return one to me. -2- Since I will be retiring as of April 1, 1991, any matters regarding this project should be addressed to Ed Chappell after that date. We have found the paint analyses you have done for us in the past most thorough and professional and are very appreciative of your fine work.

Sincerely,

Nicholas A. Pappas

Nicholas A. Pappas, FAIA

Foundation Architect

Frank S. Welsh 3/8/91

Frank S. Welsh Date

Copies to:

Mr. R. McNeil

Mr. D.A. O'Toole

Mr. E.A. Chappell

Mr. T.H. Taylor, Jr.

APPENDIX E

RESUME OF FRANK S. WELSH

RESUME

| Name: | Frank Sagendorph Welsh |

|---|---|

| Business Address: | 859 Lancaster Avenue, Bryn Mawr, PA 19010 |

| Telephone: | 215-525-3564 |

| Date of Birth: | February 11, 1950 |

| Place of Birth: | Philadelphia, PA |

Professional Background

1972-74

Architectural Technician, National Park Service at Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia, PA, the Denver Service Center Field Office with architects Penelope Hartshorne Batcheler and Lee H. Nelson: specification writing, drafting, paint investigation, stereomicroscopical analysis, minor project supervision.

1972-74

Part-time employee, Turco Paint and Varnish Company, working with paint chemist and formulator A. Richard Fitch.

1974 - present

President, The Frank S. Welsh Company, architectural coatings analysis.

Frank S. Welsh is a professional microscopist specializing in scientific research and microscopical analysis of historical architectural finishes. Since 1974, he has been in private practice as an independent consultant to national foundations and private citizens alike. Using the most advanced technologies of microscopy and microchemistry, he has performed architectural coatings analyses on more than 700 restoration projects, including Monticello; Colonial Williamsburg; Abraham Lincoln's home, Springfield, IL; Independence Hall, Philadelphia, PA; Grand Central Terminal, New York City; and the state capitols of Alabama, Florida, Maryland, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. His on-site investigations of historic buildings and laboratory analyses:

- 1.Determine the number of layers of coatings;

- 2.Identify each layer (prime coat, finish paint, glaze, varnish, shellac, wallpaper);

- 3.Identify each layer's color according to the international Munsell Color System;

- 4.Identify decorative painting such as graining, marbling, bronzing;

- 5.Analyze the composition of any coating to idenify pigments, vehicles, fibers, and to distinguish metalic coatings such as aluminum, brass and gold leaf;

- 6.Measure film thicknesses, and

- 7.Identify and analyze lead-based paints for environmental and safety concerns.

In addition, Frank S. Welsh has written and lectured for nearly two decades on old and modern paints, paint chemistry, paint history and technology, polarized light microscopy, photomicrography, microchemical paint analysis and the conservation and preservation of decorative architectural painting.

Education

| 1971 | West Chester University, West Chester, PA; B.A., Arts and Sciences. |

| 1981 | Americans and Their Civilization, I and II, University of Pennsylvania. |

| 1982; 1984 | Polarized Light Microscopy for Conservators, New York University/Walter C. McCrone (particle morphology, photomicrography, crystallography, microchemical methods). |

| 1986 | Photography Through the Microscope, McCrone Research Institute. |

| 1986-1987 | Chemistry I, II, III, Drexel University. |

| 1990 | Microchemical Methods, McCrone Research Institute |

Bibliography

- 1."Report on an Early Wall Stencil in Philadelphia", Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology, Vol. V, No. 2, 1973.

- 2."18th Century Sponge Painting in Pennsylvania", Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology, Vol. VII, No. 2, 1975.

- 3."A Methodology for Exposing and Preserving Architectural Graining", Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology, Vol. VIII, No. 2, 1976.

- 4."Paint & Color Restoration", The Old-House Journal, Vol. 3, No. 8, August, 1975.

- 5.Consulting on identification of the colors on the 1871 Harrison Bros. Color Card for inclusion (page 66) in Exterior Decoration, Victorian Colors for Victorian Houses, Roger W. Moss, Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1976.

- 6."The Art of Painted Graining", Historic Preservation (magazine of the National Trust for Historic Preservation), Vol. 29, No. 3, 1977.

- 7."Documentation of the 1902 Paint Colors of the Florida State Capitol", Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology, Vol. XII, No. 2, 1980.

- 8."18thc Black Window Glazing in Phila.", Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology, Vol. XII, No. 2, 1980.

- 9. Consulting on the original colors for the early color cards to be included in Century of Color, Exterior Decoration for American Buildings - 1820/1920, Roger W. Moss, American Life Foundation, New York, 1981.

- 10."Paint Analysis", Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology, Vol. XIV, No. 4, 1982.

- 11."Restoration of the Exterior Sanded Paint at Monticello", Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology, Vol. XV, No. 2, 1983.

- 12."Authentic Paint Colors for Historic Buildings", Newsletter of the Pennsylvania Trust for Historic Preservation, Vol. 1, No. 4, 1984.

- 13."Who Is An Historic Paint Analyst? A Call for Standards", Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology, Vol. XVIII No. 4, 1986.

- 14."Paint Investigation - Three Methods", Communique of the Association for Preservation Technology, Technical Note 10, Vol. XV, No. 6, 1986.

- 15."Particle Characteristics of Prussian Blue in An Historical Oil Paint", Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, Volume 27, No. 2, 1988.

- 16."Architectural Metallic Finishes in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries - The Great Imitators: Aluminum and Bronze", Proceedings of Historic Interiors Conference, Philadelphia, 1988.

- 17."Microchemical Analysis of Old Housepaints with a Case Study of Monticello", The Microscope, Volume 38, Third Quarter 1990.

Publications Pertaining to Completed Projects

- 1.The Magazine Antiques, p. 158, January 1977. (Paca House)

- 2.American Antiques, p. 27, June 1977. (Wentz House)

- 3.Americana, p. 24, July/August 1978.

- 4.The Magazine Antiques, p. 534, September 1978. (Hatfield House)

- 5.The Magazine Antiques, p. 788, October 1982. (Wentz House)

- 6.House and Garden, p. 82, September 1983. (Wentz House)

- 7.Progressive Architecture, p. 92 and p. 95, November, 1983. (Philadelphia City Hall and Florida Historic Capitol)

- 8.Historic Preservation (National Trust Magazine), "Solving the Mystery of Gunston Hall", p. 41, June 1984. (Gunston Hall)

- 9.Americana, p. 6, November/December 1984. (PaintpamphletTM)

- 10.Architectural Record, p. 166, October, 1985. (Wentz House)

- 11.Architecture, November, 1988. (Union Station, Washington, D.C.)

- 12.The Washington Post Magazine, "Ghosts in Alexandria", Washington, D.C., May 1, 1989.

- 13.Preservation News, "Coats of Many Colors", Washington, D.C., September, 1989.

- 14.Historic Preservation (National Trust Magasine), "Faux Arts", p. 48, January/February 1991. (Prospect)

Offices in Professional Organizations

| 1968-1976 | Vice President, King of Prussia Historical Society, King of Prussia, PA. |

| 1984-1985 | Treasurer, Pennsylvania Trust for Historic Preservation. |

Television

Maryland Center for Public Broadcasting: "The Old-House Works", Program #107, 1979.