Archaeological Investigations at Market Square, Williamsburg, Virginia: A Report on the 1989 Field Season

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1653

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1991

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS AT MARKET SQUARE, WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA: AN REPORT ON THE 1989 FIELD SEASON

| Page | |

| Acknowledgments | ii |

| List of Figures | iii |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Research Plan | 2 |

| History of Market Square | 4 |

| The Market House | 4 |

| The Powder Magazine | 9 |

| Previous Archaeology | 13 |

| Methods | 15 |

| Archaeological Results | 18 |

| Structure B | 18 |

| Structure A | 22 |

| Inside the Magazine Wall | 26 |

| Structure E | 27 |

| Guard House | 27 |

| Conclusion | 28 |

| Bibliography | 29 |

| Appendix A. Master Contexts | 32 |

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our appreciation to all those involved in the project. Of course, we owe our greatest thanks to the field crew from the 1989 summer archaeological field schools of the College of William and Mary. Members of the first session included:

| Richard Cartwright | Julie Gurdin | Gretchen Reimer |

| Peggy Clark | Jay Harkins | Kerry Saltmarsh |

| Ywone Edwards | Audrey Horning | Andrea Williams |

| Mike Groot | Jackie Lee | |

| Stefanie Groot | Sean O'Neil |

Members of the second session included:

| Vince Badrinath | Mike Manning | Jeff Smith |

| Heather Bell | Gerard Pham | Chris Smith |

| Tim Boyle | Blair Pogue | Susan Ullman |

| Chris Daniels | Mary Jane Rubinski | |

| Jennifer Jones | Jennifer Schlegel |

We would also like to thank several volunteers who assisted us in the field, including Mary Bowman, David Hudgins, Juliet Kmetz, Martha Moore, Gene Peacock, Katherine Snodgrass, Sylvia Teaves, Susan Trevarthen, and Stan Witkowski.

The square supervisors—Mike Bradshaw and Susan Wiard in the first session, Richard Cartwright and Ywone Edwards in the second—were tremendous, providing most of the one-to-one instruction in field techniques. John Burton, Lu Gordon, Scott Craig, and Amy Kowalski ran the laboratory and identified and coded the artifacts, under the general supervision of Collections Research Specialist William E. Pittman.

The staff of the Magazine could not have been more helpful. In addition to answering visitors' questions and allowing us to share the Guard House, they provided valuable historical and artifactual information based on their extensive knowledge of the military use of the site. We would particularly like to thank John Hill, the Keeper of the Magazine; Collier Harris; and Jeff Geyer.

Our colleagues provided an enormous amount of help. Carl Lounsbury's 1986 report on the market house was invaluable, and he often came to the site to help us interpret certain architectural features. Martha McCartney alerted us to the 1781 Samuel DeWill map showing the market house.

Maps and graphics were provided by draftsperson Kimberly Wagner; photographs were supplied by photographer Tamera Mams. The field maps were digitized by Susan Trevarthen and Lucie Vinciguerra. Context records were entered by Mike Bradshaw.

List of Figures

| Page | |

| 1. Location of Market Square | 5 |

| 2. Buildings on Market Square in the twentieth century | 6 |

| 3. Frenchman's Map, 1782 | 8 |

| 4. The Powder Magazine in the nineteenth century | 12 |

| 5. 1934 excavation area | 13 |

| 6. 1948 excavation area | 14 |

| 7. Sample context record | 16 |

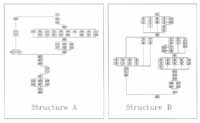

| 8. Harris matrix diagrams | 17 |

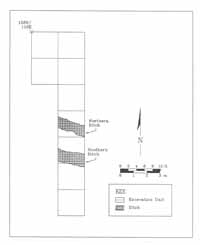

| 9. Excavation area | 18 |

| 10. Simplified Harris matrix for Structure B | 19 |

| 11. Features discovered near Structure B | 21 |

| 12. Simplified Harris matrix for Structure A | 22 |

| 13. Foundation of Structure A | 23 |

| 14. Features discovered near Structure A | 24 |

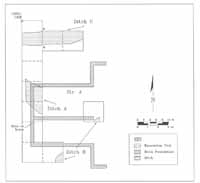

| 15. Virginia half-penny found in fortification ditch | 25 |

| 16. Section drawing of fortification ditch | 26 |

Chapter 1:

Introduction

In the summer of 1989, archaeologists from Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Archaeological Research, in conjunction with two archaeological field schools jointly sponsored by the Departments of History and Anthropology of the College of William and Mary, investigated the so-called "Market Square" in the center of Williamsburg's Historic Area. The aim of the project was, first, to discover the remains of the 1757 market house mentioned in newspapers and administrative records, and second, to study the military and non-military uses of the area on the eastern side of the Public Magazine.

The project also served as a chance to experiment with innovative field recording and analytical systems designed to refine the study of spatial patterning. It was felt that this was particularly important if and when the market house was discovered, as many research questions were focused on the spatial layout and organization of the area in and around the market building.

Excavation was directed by staff archaeologists David F. Muraca and Gregory J. Brown of the Department of Archaeological Research, under the general supervision of Director Marley R. Brown III. Field supervisors included Department of History graduate assistants John Burton, Susan Wiard, Ywone Edwards, and Richard Cartwright, along with Michael Bradshaw. Laboratory processing and analysis was performed by John Burton, Scott Craig, Lu Gordon, and Amy Kowalski, under the direction of Collections Research Specialist William Pittman.

Chapter 2: Research Plan

The search for the location of the market house essentially had its origin in a 1986 report titled "The Williamsburg Market House: Where's the Beef?," by Carl Lounsbury of Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Architectural Research. Suggesting its importance to the proper interpretation of certain aspects of the town's economic and social life, Lounsbury urged that the building, if found, be reconstructed at some time in the future. Meanwhile, questions about the function of the market were arising from projects undertaken by members of the Foodways Forum, including the work of zooarchaeologists in the Department of Archaeological Research. Many of these questions centered on the market's physical layout, its administrative as well as practical organization, its frequency, and its character in terms of amount and variety of foods sold.

Archaeological investigation, it was felt, could provide some clues about many important aspects of the market; in particular, the study of animal bones, seeds, plant phytoliths, shell, and chemical constituents of the soil could suggest where and in what concentrations certain foodstuffs were being marketed. Artifactual evidence, along with the architectural characteristics of the building, could suggest the complexity, organizational framework, and sheer size of market functions. The discovery of large scales or weights could suggest the level of administrative control, while the location of meat hooks and butchering implements could reveal areas of meat storage or preparation. Postholes and other soil stains could pinpoint the exact location of small sheds or tents used by itinerant vendors, and perhaps pathways could be located which were used by the fishermen and hucksters who sold their merchandise from open carts.

Coincidentally, new interpretive schemes were being planned for depicting the military presence in town, which had in the past been confined to the area around the Powder Magazine. A temporary campsite was established in the woods behind the Tayloe House north of Market Square, in order to show the type of military encampments common after 1750. At the same time, it was felt that the Magazine itself had to be restudied in light of new evidence about its place in the community.

In "A Prospectus for Magazine Interpretive Research" (White 1986), it was argued that:

Two areas of research must be addressed. First, are the physical environs, including the objects and items kept at the Magazine and their method of storage. Second, is the process and the manner of supplying military forces and its connection to the community and government of Virginia. The investigation of these questions involves the resources of the Departments of Archaeology, Architecture, Collections, and Research(White 1986:1).3

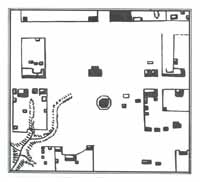

The study of the "physical environs" of the Magazine, it was hoped, would address questions about the use of the interior yard inside the Magazine wall, the divisions of space outside the wall, the construction dates and functions of several structures shown on the 1782 Frenchman's map, and the true function of the Guard House (M. Brown 1988).

In light of these often-diverse goals, and since the excavation was virtually unfunded, therefore limiting its scope, it was decided that a sampling strategy would be used. Testing was concentrated along the edges of two known buildings—Structures "A" and "B"—with intermittent test holes placed around other parts of the property. The remainder of this report discusses the findings from this limited archaeological study, with reference to the relatively more promising documentary record.

Chapter 3:

History of Market Square

Since the founding of Williamsburg in 1699 out of an earlier settlement called Middle Plantation, the Market Square (Figure 1) has been an important part of the town. When Governor Francis Nicholson laid out what he had intended to be a model city, the square was left for public community interactions and, perhaps, as an aesthetic element much like modern urban parks and green space. Reps, in fact, has suggested that it was used to display an elaborate design by the inclusion of diagonal streets, with the roadways forming a huge "WM" cipher (1972:166-169).

Ideally situated for community functions, the square held some of the town's major public buildings. Around 1716, an octagonal brick building was constructed on the south side of the square to serve as the public powder magazine. In 1757, a carpenter was hired to construct a market house. By 1770, a court house was built on the north side of the square, facing Duke of Gloucester Street.

By the next century, the square held a large Baptist church, constructed around 1850, and the so-called "Bell Hospital." A hotel, the "Toot-an-kum-in" garage, a real estate office, a grocery store, a "tea room," and several bungalows were added by the early twentieth century (Samford 1985; Figure 2).

Because the dual goals of the project involved the investigation of the market house and the evaluation of the use of space around the Magazine, the remainder of this chapter will concentrate on the detailed history of these two buildings.

The Market House1

In 1699, when Williamsburg became the capital of Virginia, the governor was given the power to grant a market to the newly-established city. Although there had been an earlier act in 1649 granting Jamestown a market "to be holden every Wednesday and Saturday … between the hours of eight in the forenoon and six in the afternoon"(Hening 1823:I:362), there is some doubt that one was ever actually established. In Virginia, "towns" were quite unlike the centralized commercial centers of New England. The town market, an important economic and social institution in English villages as well as in the northern colonies, was apparently slow to take hold, despite administrative efforts throughout the eighteenth century.

5 Figure 1. Location of Market Square (adapted from ca. 1800 "College" map).

Figure 1. Location of Market Square (adapted from ca. 1800 "College" map).

In 1705, a series of "Town Acts" provided for sixteen new towns in Virginia, providing each with, among other things, "a market at least twice a week, and a fair once a year, … a merchant guild and community with all customs and libertys belonging to a free burgh, … [and] benchers of the guild hall for the better rule and governance of the town"(Hening 1823:III:408)

. That same year, another act provided the trustees of Williamsburg with the power to "enlarge the market place"(Hening 1823:III:431)

. Nothing seems to have been done about building a market house or even holding a regular market, however, since in 1710 Governor Alexander Spotswood indicated that

6

Figure 2. Buildings on Market Square in the twentieth century (from 1921 Sanborn map).

he was "inclined to appoint Weekly Markets" in the town (McIlwaine 1928:III:251). Three years after, he proposed, apparently unsuccessfully, that a market house be built (Palmer 1875:I:169).

Figure 2. Buildings on Market Square in the twentieth century (from 1921 Sanborn map).

he was "inclined to appoint Weekly Markets" in the town (McIlwaine 1928:III:251). Three years after, he proposed, apparently unsuccessfully, that a market house be built (Palmer 1875:I:169).

As Carl Lounsbury suggests in his 1986 report on the market house, it is likely that the lack of a regular market in Williamsburg in the early eighteenth century was due to a small resident population and an abundance of available farmland in the surrounding countryside. Only during "Publick Times," when councilors, burgesses, and various petitioners descended upon the town to attend court or participate in the colony's government, was there a large enough population to support a regular market.

In 1722, the city was granted a charter, which provided that two markets could be held each week, on Wednesdays and Saturdays. Tolls were established for various products, but were limited to a "twentieth part of the Value of any such Commodity," sixpence for every "Beast," and threepence for every hog (Gill 1983). As was common in such legislation, citizens of the town were required to pay only half of the toll.

In 1757, the town was permitted to pass laws increasing the frequency of market days. Both Williamsburg and Norfolk were permitted to hold markets six days a week, 7 excepting only Sunday. In the same year, a market house was built on Market Square, near the center of town and about halfway between the Capitol and the College. One or two wooden buildings might have stood on Market Square at this time; it is just as likely, however, that the building constructed in 1757 was the first market house (Lounsbury 1986).

The form of the building is suggested by a notice in the Virginia Gazette of April 22, 1757:

(Virginia Gazette, Hunter, 22 April 1757).April 22, 1757

The Gentlemen appointed by the Common Hall of the City of Williamsburg, will meet on Tuesday next at the House of Mr. HENRY WETHERBURN, at Six O'clock in the Evening, in order to agree with a Carpenter for building a Market-House in the said City

Although the exact specifications for the building are not known, Lounsbury suggests that it was probably a simple wooden building (since the construction was let out to a carpenter), resting on brick foundations and most likely with a shallow hipped roof with overhanging eaves (1986:25-28). In 1770, several citizens petitioned to turn the old guard house near the powder magazine (see below) into a market, possibly indicating that the original had been torn down or burned (or, alteratively, that the market was growing and had outgrown its existing facilities). By 1797, the brick powder magazine itself had become the market house (Morse 1797:594). It continued as such until the early 1830s, when a new market house was built (Martin 1835).

There is only one real description of the Williamsburg market in the eighteenth century, that being a sarcastic commentary in the Virginia Gazette by a citizen using the pseudonym "Timothy Telltruth":

In all well regulated cities and towns the utmost regard is paid to the health and circumstances of the inhabitants, by those in power enacting such laws as deter butchers, bakers, &c. from exposing any thing to sale but what is good in quality, and at a certain fixed rate. We of the good town of Williamsburg, metropolis of Virginia! have but too much reason to complain of being neglected in those particulars; for here meat for poverty not fit to eat, and sometimes almost spoiled, may hang in our market for hours, without any notice being taken of the venders of it; and any person may ask what price for his commodity that his conscience will allow him, which is generally exorbitant enough, especially on publick times, or when little meat is at market. And if a man has not got money enough to purchase a whole quarter of meat, the butcher generally demands a penny a pound extraordinary to cut it. In the same manner we are treated about all other provisions, the feller always taking advantage when in his power. In Norfolk, I have heard that the markets are so regulated there that good meat must only bear such a price as the Magistrates think reasonable; and the butcher is obliged to cut his meat upon a farthing a pound being paid more than he demands the quarter. An example worthy of imitation.—And the bakers are suffered to make their bread of what weight they think proper, and to put such unwholesome ingredients into it, and bake it of such bad flower, as must be very prejudicial to the health of those who eat it. At this very juncture the bread they bake daily, and sell to the inhabitants, justly entitles them to the pillory, if they had their desserts. A good heavy fine, in all likelihood, would put a stop to their iniquitous practices, so detrimental to the inhabitants… . (Virginia Gazette, Purdie and Dixon, September 7, 1768).8

Nonetheless, the market persisted. In the 1780s, the German traveler Johann David Schoepf found that "provisions [in Williamsburg] are very cheap: butchers' meat 2 pence; hog meat 3 pence the pound; a turkey-cock 2 and a half shillings; a turkey-hen 2 shillings; a dozen pullets 6 shillings" (Schoepf 1788:II:81). In 1795, the noted resident St. George Tucker related that "The Market, though not very regular, nor well supplied, yet furnishes excellent meats and poultry in their season. They have also fish, crabs, oysters, wild fowl, and excellent butter, vegetables, and fruit" (1795:196).

Figure 3. Portion of ca. 1782 Frenchman's map showing area around Market Square.

Figure 3. Portion of ca. 1782 Frenchman's map showing area around Market Square.

The exact location of the market house has never been determined. A map drawn in 1781 (Anonymous 1781) shows the "Markethouse" on what appears to be the southern side of Duke of Gloucester Street across from the courthouse. The 1782 Frenchman's map (Figure 3) shows four rectangular buildings east of the Magazine on the south side of Market Square. Lounsbury (1986) suggests that one of these buildings, the so-called Structure B discovered by George Campbell in 1934, is the likeliest candidate for the market house in terms of size and physical location. Others have suggested, however, that the market house was not on the south side of Market Square at all, but rather was on the north side, away from the activities associated with the still-standing Magazine (James M. Knight, personal communication).

The Powder Magazine

Despite the presence of a town market, it is clear that the most dominating structure on the Market Square has always been the brick powder magazine. It was built around 1716 by then-Governor Alexander Spotswood, an ex-soldier in the Duke of Marlborough's continental army (Lowe 1972). Appalled by the lack of military preparedness, Spotswood proposed to the Assembly:

That as soon as conveniently it may be done, there shall be erected and finished one good substantial house of brick, which shall be called the magazine, at such place as the lieutenant-governor shall think proper: in which magazine, all the arms, gun-powder, and ammunition, now in the colony, belonging to the king, or which shall at any time hereafter be, belonging to his majesty, his heirs, or successors, in this colony, may be lodged and kept. For the building and furnishing which magazine, there shall be laid out and expended any sum or sums of money, not exceeding two hundred pounds(Hening 1823:IV:55).

Probably built by Henry Tyler from a design by Spotswood himself, the octagonal building was ready for use in February 1716. At that time, Spotswood reported that it had "300 firelocks, 300 Soldiers' Tents, 154 barrels of Powder, 3 Ton 7 lb of Musqt ball, 2 field-pieces, with their Carriages and furniture …" (Brock 1882-1885:II:140).

Not until 1755, at the start of what would variously be called the Seven Years War or the French and Indian War, was the Magazine made stronger. In that year Governor Robert Dinwiddie stated in an address to the House of Burgesses that:

The Magazine in this City is much expos'd, I therefore think it absolutely necessary to have a Guard-Room built, and a proper Guard established, to be by due Rotation constantly in duty. I hope you will agree w'th me that this is necessary, and accordingly appropriate a sufficient Sum for build'g the Guard-Room and paying the Guard (Brock 1882-1885:II:135).

The Assembly agreed not only to create a guard house and provide for a permanent guard, but to fortify the Magazine itself:

… by the authority aforesaid, That Peyton Randolph, esquire, Carter Burwell, John Chiswell, Benjamin Waller, and James Power, gentlemen, or any three of them, be and are hereby appointed directors, to treat and agree with workmen, to erect a high and strong brick wall, to enclose the said Magazine, and to build a guard house convenient thereto. And that the said directors apply to the governor, to issue his warrants to the treasurer of the colony, for the payment of such sums of money, as they shall from time to time have occasion for the purposes aforesaid…(Hening 1823:VI:528).

A notice was soon placed in the Virginia Gazette:

The Persons appointed by Act of Assembly, to agree with Workmen, for the building of a Wall round the Magazine, and a Guard House, will meet for that purpose on Wednesday next(Virginia Gazette, Hunter, 5 September 1755).10

The location of this guard house is unknown. Campbell (1934) thought that it was Structure B, directly east of the Magazine, while later excavation in 1948 by James Knight disclosed another candidate about thirty feet to the south. This long rectangular building was reconstructed and is now interpreted as the guard house, but there is no positive documentation that it actually ever served that function.

In February 1756, Governor Dinwiddie reported that:

… The stores in the Magazine of this Gov't are as follows: 520 whole B'ls and 180 half B'ls of Gun Powder; 17 Caggs of shott, about thirty lb. weight; 8 Small Caggs of Flints; 28 Halberts and 12 Drums; no Small Arms, having sent Gen'l Braddock 400, and N. York and the Jersies 1300 and 800 to the Soldiers now in the pay of this Colony(Brock 1882-1885:II:344).

Other periodic inventories present a good picture of the stores held in the Powder Magazine during the next twenty years. In 1764, it was reported that:

… there are now in the said Magazine two Brass Cannon and two Brass Mortars, which are useless; also about 13,000 lbs. of Gunpowder, which is old, and the Barrels decayed and in bad order; also a Quantity of Soldiers Clothes, Hats, and Shoes, which at the present are of little Use, and will be entirely ruined if they remain there: That there are also 102 Tents, which are old and useless; and 14 new Ones, which may be of Service: That there are also two Hogsheads of Cantins and Tin Kettles, one Tierce of Leather Shot Bags, and another of Canvas Knapsacks, and a Quantity of Leather Belts and Slings, old Drums and Drum Rims, which are useless; and a Number of Cartouch Boxes, in very Bad Order: That there are also upwards of 500 old Firelocks and Barrels, which might be repaired at 12s.6d. each, but are not worth the Expense; and there is a Tub of Gun Flints, which may be reserved for Use(McIlwaine and Kennedy 1905-1915:10:306).

As war approached in 1775, a committee appointed to inspect the building reported that they:

… found therein nineteen Halberts, one hundred and fifty seven trading Guns in pretty good order, but very indifferent in kind, fifty one Pewter Basons, eight Camp Kettles, one hundred and eight new Muskets without Locks, and about five hundred and twenty seven old Muskets, the barrels very rusty, and the Locks almost useless, twelve hundred Cartouch boxes, fifteen hundred Cutlasses with Scabbards, one hundred and seventy Pistol Holsters, one hundred and fifty old Pistols, or thereabouts, with and without Locks, fifty Mallets, two bundles of match Rope, two hundred Cantines, thirty five small Swords in bad order, one Tent and Tent Poles, one Hogshead of Powder Horns, one hundred and twenty seven Bayonets, one hundred Knapsacks in the Smiths Shop, and that part of the Magazine called the Armory, also one half Barrel of Dust and rotten Powder, one half barrel and a quarter of unsifted Powder, tolerably good, in the Powder Room, that has no communication with the Armory, also five half Barrels of loose Powder buried in a Hole in the Magazine yard, the top of which, (in quantity about two half barrels) was totally destroyed by the late Rains, the rest very damp, but quite sound …(McIlwaine and Kennedy 1905-1915:13:223-224).

Lowe (1972) provides an excellent overview of the complicated series of events preceding and during the Revolutionary War, including Lord Dunmore's famous attempt to secretly remove the Colony's gunpowder. It appears that the building itself was not 11 damaged during the War, although stores were transferred to the new capital at Richmond by the end of 1780. After that date, the Magazine ceased to serve its primary purpose; by 1796, in fact, it had been appropriated for use as a market house. A letter from St. George Tucker, a prominent citizen of the town, indicates that at this time:

…The hospital for lunatics, a church, the town and county courthouse, and a magazine now occupied as a market house, complete the list of public edifices: neither of these appears to have been completed with any view to architectural fame(Tucker 1795:195).

A new market house was built in the early nineteenth century, but it appears that the lower floor of the Magazine also continued to be used as such for several more decades. In 1857, the local newspaper described:

Oct. 7, 1857

Market Exercises.—On Thursday last, the market exercises commenced. The Marketonians opened the meeting and seemingly without the least disposition to chant or give gloria in-excelsis to the fathers for having so kindly considered their comfort and interest by having the relishable Horn minus mint and whiskey fixed for them on that morning…. The Horn however will prove a source of revivification to more than vendors of meat—even our citizens are allowed to participate in its comforts, all they will have to do, will be to walk up to the Powder Horn and help themselves… . The dead meats we there saw were very nice and tempting, sufficient to excite the palate of the most luxorious epicure

(Ewing 1857).

The second floor, however, was given over for use as a church meetinghouse. John Charles describes it in his recollections of Williamsburg immediately before the Civil War:

… The old "Powder Horn" looks much like it did in the "long ago"… The upper floor was used as a church, by the Baptist, before they built their present church, while the lower floor was used as a "market house" before the War and afterward used as a stable until it was bought and restored to its present condition by the A.P.V.A.(Charles 1928:40).

During the War, the Magazine was used as a Confederate arsenal. It later housed a dancing academy and a livery stable (Figure 4) before being purchased by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (A.P.V.A.) in 1889 (Yetter 1988).

12 Figure 4. The Powder Magazine in the nineteenth century. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Negative L525)

Figure 4. The Powder Magazine in the nineteenth century. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Negative L525)

Chapter 4:

Previous Archaeology

The Market Square area was tested twice previously: in 1934, by George S. Campbell, and in 1948, by James M. Knight. Campbell's 1934 investigation, intended to identify the guard house from the buildings shown on the Frenchman's map, was concentrated in several small areas to the east of the Magazine (Figure 5). Campbell apparently extensively excavated these areas, and found three structures: Structure A, a 37-by-63-foot cruciform building on the edge of Francis Street, located 115 feet southeast of the Magazine; Structure B, a 19-by-29-foot rectangular building 30 feet east of the Magazine; and Structure C, a 40-by-60-foot building a little farther to the north. Only Structures A and B appeared to be colonial; Structure C was apparently an early nineteenth-century public building.

Structure A was nearly intact, including a 14" wide interior partition wall on the west side. According to Campbell's notes,

Foundation at "A" was discovered rather near the surface of existing grade and averages four brick courses in depth. On examination of the brickwork it was noticed that the walls were 13" in thickness laid in Flemish bond in a mortar of yellowish color withFigure 5. 1934 excavation area.14 oyster shell content. It could not be ascertained when this building existed, but the general character and appearance of the brickwork gives the feeling of colonial workmanship. The general plan would suggest a bldg similar to that of the "old court house" and may have served as such as bldg. (according to Judge Frank Armistead)(Campbell 1934).

Structure B, just to the west of a still-standing mid-to-late nineteenth-century Baptist church, was much more fragmentary. Portions of intact foundation wall were found on the north and south sides, along with a line of brick bats on the west. Campbell stated that:

Foundation at "B" was discovered in following the Frenchman's Map which lead to fragmentary remains of a foundation for a brick building were discovered well below grade at a similar depth to that of the Magazine. The brickwork is undoubtedly of colonial origin with oyster shell mortar of eighteenth century coloring & aggregate. The full extent of the foundation could not be fully ascertained owing to the removal of a greater portion of it. Considerable quantities of brick bats were found from which the continuation of the wall could be traced, thus giving an appropriate dimension in length, the width is clearly defined by remaining fragments of footings. The foundation may possibly be that of the Magazine guard house(Campbell 1934).

In 1948, after the large Baptist church had been razed, James M. Knight cross-trenched the entire area, apparently avoiding Campbell's excavations. He discovered two additional buildings: a 19 by 51 foot rectangular building later reconstructed as the Guard House, and another building composed only of a single line of "fragments of shell mortar and brick, located approx. 12" below grade" (Knight 1948; Figure 6).

Chapter 5:

Methods

The Market Square project was the first Colonial Williamsburg excavation, and the first major excavation in the United States, that utilized GEOBASE 4D, an integrated excavation database and geographic information system developed by Dominic Powlesland of the Heslerton Parish Project in North Yorkshire, England. Essentially a method of field recording that emphasizes the determination of the exact geographic position for each artifact, it allows one to analyze spatial patterning in a way not possible when using traditional archaeological methods.

The Department of Archaeological Research uses an excavation strategy called "open-area" excavation, where large horizontal areas are cleared and dug without intervening balks of standing soil. Profiles of soil stratigraphy are drawn of the most representative face and later compiled into a composite section drawing, while plan drawings are made of fully-exposed features. In a slight modification of this technique, excavations at Market Square were performed in contiguous two-by-two-meter units; in a few cases isolated one-by-one-meter test units were placed in other areas.

Each excavated layer or feature, called a context, was recorded using a standardized context record form (Figure 7). Horizontal position was noted in reference to a coordinate grid established on the site, and was recorded vertically by shooting the top and bottom of the context with a laser theodolite. Measurements were made in centimeters. Separate plan drawings were made of each context, and these so-called "single-layer plans" were later digitized and consolidated using AutoCAD™ drawing software.

All artifacts were recovered by context. In significant layers or features, each artifact was first "piece-plotted" using a laser theodolite, which recorded the horizontal and vertical position of the find. A plastic artifact bag was labelled with the "tag number" corresponding to the data recorded in the theodolite. This data was later integrated into the database containing the artifact and its other attributes.

Artifactual and contextual information was entered into the FoxBase+™ software package, from which it was translated into GEOBASE format. Plans and drawings were similarly translated from AutoCAD into GEOBASE.

Laboratory processing was limited to the washing and identification of all objects in the field lab (actually a room in the Magazine Guard House). No cross-mending was performed due to the lack of material from most contexts. Similarly, the lack of faunal material precluded zooarchaeological analysis. Soil samples were taken from all contexts. However, due to the lack of intact eighteenth-century deposits, no palynological, parasitological, or phytolithic analyses were performed.

16 Figure 7. Sample context record.

Figure 7. Sample context record.

Figure 8. Harris matrix diagrams.

Figure 8. Harris matrix diagrams.

Stratigraphic relationships on the site were recorded using the so-called "Harris matrix," a diagrammatic approach first developed by Edward Harris at the Winchester site in south-central England (Harris 1979). Matrix charts were created for the areas around Structures A and B (Figure 8), and later consolidated into simplified site diagrams (see Figures 10 and 11). The primary stratigraphic units were assigned master context numbers in order to facilitate recording; topsoil was assigned master number M1, the layer below topsoil M2, etc. A complete list of master contexts is given in Appendix A.

18Chapter 6:

Archaeological Results

Structure B

Structure B, a rectangular building measuring 19'3" north-south by 28'10" east-west, was discovered in 1934 and interpreted, at that time, as a guard house. Portions of the north, west, and south foundation walls were uncovered and mapped (Campbell 1934).

As it was this building that Lounsbury suggested to be the market house, re-excavation in 1989 was aimed at recovering evidence of its function, spatial characteristics, and precise construction and destruction dates. Given the sparse documentation, there was no evidence that it had been damaged since 1934. The

19

Figure 10. Simplified Harris matrix for Structure B.

Campbell map of that date stated that the foundation was "well below grade." However, another note on the map stated that "after excavation work was completed + re-filled this entire block was re-graded."

Figure 10. Simplified Harris matrix for Structure B.

Campbell map of that date stated that the foundation was "well below grade." However, another note on the map stated that "after excavation work was completed + re-filled this entire block was re-graded."

Excavation was performed in a series of 2x2 meter units along what would have been the eastern foundation wall. Unfortunately, no evidence of Structure B was found, suggesting that grading and other disturbances relating to the destruction of the nearby Baptist church in late 1934 had destroyed virtually all archaeological data in the area. A brief description of what was found will be given below.

Modern Intrusions

After a layer of modern topsoil, 10 cm thick, was removed, excavators encountered a series of utility trenches and other modern disturbances which had obliterated the earlier building. These included a long telephone line trench (M3/4) running north-south through the western portion of seven units; a second trench (M14/15) found in the western half of the southernmost unit, containing two abandoned utility lines; and, most prominently, a huge trench (M7/8) running east-west through the central squares, at least three meters wide and more than 2.5 meters deep. It is likely that this 20 was the result of the excavation of some sort of oil tank or other buried feature associated with the Baptist church.

Other intrusive deposits, all probably relating to the destruction of the church in 1934, were found north of this tank trench, obliterating all eighteenth- and nineteenth-century archaeological evidence in seven of the ten units. These included three concrete piers, probably part of some sort of porch structure for the church. In addition, the two trenches found in the southernmost unit, along with a modern posthole related to a previous restraining fence erected by Colonial Williamsburg, destroyed all earlier evidence in this area as well. The only reasonably intact archaeological stratigraphy, therefore, was in the eastern portions of two units and the southeastern portion of a third.

Coal Concentration

A small coal concentration or spread (M46) was found on the eastern side of unit 148N/120E under an earlier twentieth-century topsoil layer. No associated artifacts were recovered.

Coal Layer

An uneven layer of brown sandy loam with crushed lumps of coal (M16) was found in units 146N/120E and 148N/120E. Based on associated artifacts including cut nails, this layer, 2-8 cm thick, was probably deposited during the early to mid-nineteenth century.

Eighteenth-Century Ditches

Two parallel shallow ditches (Figure 11) were found on the lowest stratigraphic level, under (and therefore predating) the coal layer. The southernmost ditch (M49/50), about one meter wide, was 25 cm in depth, while the northern (M47/48), about the same width, was only 15 cm deep. The fill of both ditches, however, contained fragments of creamware, a refined earthenware first manufactured in 1762 and not seen in Virginia before around 1768. Thus, it is clear that the ditches were dug mid-century and filled in and abandoned after the late 1760s. Their purpose is unknown, although the date and orientation suggests that they may have been part of Revolutionary War fortification efforts around the Magazine.

21Summary of Features

Because the ditches were under the area of Structure B, running beneath what would have been (had it survived) the eastern wall of the building, they provided evidence that Structure B itself could not have been built until after 1762. Therefore, it is stratigraphically impossible that Structure B represents the 1757 market house. The coal layer, it appears, is an nineteenth-century deposit, unrelated to either the ditches or the building. The presence of a concrete post intruding the coal concentration suggests that the coal may have been associated with the mid-to-late nineteenth-century Baptist church. The more extensive coal layer may have been the remains of some sort of industrial activity after the destruction of Structure B but before the construction of the church.

Based on the lack of evidence in the test squares on the eastern side of Structure B, and the apparent extent of disturbance in the area, it was felt that no purpose would be served by further exploration. A small test unit was dug near what should have been the southwestern corner of the foundation in order to see whether intact stratigraphy was present in this area; this revealed only modern disturbances to a depth of about a meter.

Structure A

Structure A was a cruciform building measuring 36'10" north-south by 62'8" east-west. The foundation was re-discovered in 1985 when the excavation of a narrow utility trench which cut through the center of the building, suggesting that, unlike Structure B, it had not been destroyed by later re-grading after its initial discovery.

Excavation was centered along the western wall of the foundation, beginning just south of the southwestern corner. Another unit was placed at the end of the interior partition wall, in order to discover whether the wall actually stopped abruptly (as was mapped in 1934) or was intruded and destroyed at this point by some sort of later disturbance.

Figure 12. Simplified Harris matrix for Structure A.

Figure 12. Simplified Harris matrix for Structure A.

Modern Intrusions

Relatively few modern disturbances were found around Structure A, but the previous archaeological effort in 1934 had effectively obliterated almost half of all layers associated with the building. Among the most significant later disturbances was a large 23 hole measuring at least two meters north-south and 80 cm east-west, which was found some five meters north of the northwestern corner of the foundation. This intrusion appeared directly under topsoil and thus is obviously modern. It was excavated to a depth of about one meter.

Brick Foundation and Builders Trenches

The foundation for Structure A (Figure 12) was discovered only a few centimeters below surface, under a thin layer of modern topsoil. It consisted of a one-and-a-half brick wide foundation bonded with sand-based mortar. The interior partition wall was bonded into the exterior wall.

Figure 13. Foundation of Structure A, looking west. (Colonial Williamsburg Dept. of Archaeological Research)

Figure 13. Foundation of Structure A, looking west. (Colonial Williamsburg Dept. of Archaeological Research)

As noted in 1934, the wall, 33 cm (13 inches) wide, was on the average four courses high and surrounded by traces of a 10 cm wide builder's trench. The builder's trench (M27/28) contained a variety of ceramics, including pieces of Fulham stoneware, delftware, creamware, pearlware, porcellaneous ware, and white salt-glazed stoneware, along with a few cut hand-headed nails, providing a terminus post quem of 1805.

A small circular hole, 6 cm in diameter, was found in the top brick 230 cm north of the southwestern corner of the foundation. Archaeological collections specialist William Pittman (personal communication) suggests that this may have been the location of a hinge pin for a door or gate.

Eighteenth-Century Ditches

Figure 14. Features discovered near Structure A.

Figure 14. Features discovered near Structure A.

At least two ditches, one running northwest-to-southeast (Ditch A) and the other northeast-to-southwest (Ditch B), were found on the lowest stratigraphic level (Figure 14). Both were overlaid by the building foundation, and thus predated the construction of Structure A. Ditch B (M36/37) was found in two units over three meters apart, and appears to run roughly perpendicular to Ditch A. It was filled with a brown silty loam containing creamware, pearlware, whiteware, white salt-glazed stoneware, black-glazed redware, wine bottle glass, cut nails, and lead shot. Ditch A (M32/33), also filled with a brown silty loam, contained very few artifacts of any kind. The function of the ditches is unclear; most likely, despite their different orientations, they were part of some sort of fortification efforts around the Magazine between 1755 and 1775.

Revolutionary War Period Fortification Trench (?)

A deeper and more pronounced ditch, 120 cm in diameter and 90 cm deep, was found in several units north of Structure A. Called Ditch C, this feature, which appears to curve northward at the eastern end of the excavation area, seems to represent a large roughly octagonal or circular fortification trench running around the Magazine. The date of the trench is suggested by a 1773 George III Virginia half-penny (Figure 14) found in a silted layer at the very bottom of the ditch. These coins, put into circulation in late February or March 1775 and mostly bought up soon afterward (Noël Hume 1969:168), are commonly found on late eighteenth-century sites in the area. The presence of the coin, however, clearly pinpoints the date before which the ditch could not have been filled, and thus suggests that it was probably open during at least part of the period immediately preceding the Revolutionary War.

Figure 15. Virginia half-penny found in fortification ditch.

Figure 15. Virginia half-penny found in fortification ditch.

Other artifacts recovered in the upper layers of the fill of the ditch included creamware, whiteware, annular pearlware, delftware, black-glazed redware, Westerwald stoneware, wine bottle glass, window glass, a few pieces of animal bone, and a wire nail. Many of these were almost certainly deposited after the ditch had been abandoned and silted in (Figure 16).

Summary of Features

Stratigraphic, artifactual, and architectural evidence indicates that Structure A was constructed during the early nineteenth century, and cannot be the 1757 market house. The building is, however, likely to be the market house described in Joseph Martin's 1835 Gazetteer. Unfortunately, previous archaeology in 1934 has destroyed almost all of the refuse layer that must have been associated with this building; little if any suggestions can be offered regarding the organization and layout of the surrounding area. Likewise, the presence of a trench at the end of the interior partition wall prevented any chance of seeing whether the wall continued past this point at one time. Excavations in 1934 indicated that there was no corresponding partition wall in the eastern half of the building.

The pre-1775 ditches, particularly Ditch C, suggest a fairly major fortification effort. Determination of the exact shape of the fortification, however, must await further excavations in various areas south and east of the Magazine.

26Inside the Magazine Wall

Three 1x1 meter-square units were excavated inside the Magazine wall on the southern side of the building, in order to determine the potential for further archaeology aimed at reconstructing aspects of military use of the Magazine. Each unit revealed a 15 cm thick layer of eighteenth-century sheet refuse, lying roughly 20 cm below surface beneath modern topsoil and an oyster shell pathway. The sheet refuse, which was excavated in arbitrary 10 cm levels, contained late eighteenth-century artifacts at the top, including annular pearlware. Earlier eighteenth-century artifacts, including white salt-glazed stoneware and Fulham stoneware, were recovered toward the bottom.

Structure E

A series of three small test units were excavated in the vicinity of Structure E, the small building discovered by James Knight in 1948. The goal was to discover whether eighteenth-century layers and features were present in the area or whether they had also been obliterated by the destruction associated with the razing of the Baptist church.

Excavation revealed an apparently intact eighteenth-century layer (M65) below modern topsoil, at a depth of 35 cm below surface. The only artifact recovered was a piece of English bone china, providing a terminus post quem of 1800. At least one eighteenth-or early nineteenth-century posthole (M66/67) intruding this layer was discovered.

Although somewhat damaged by earlier archaeology and the destruction of the Baptist church nearby, it appears that some refuse deposits have survived in this area. However, the fact that Knight could only find a small portion of one foundation wall in 1948 suggests that other disturbances may have obliterated much of the building.

Guard House

Six test units excavated around the reconstructed Guard House suggested that all cultural layers had been destroyed during the reconstruction. The units, which extended up to six meters away from the building, revealed no intact stratigraphy whatsoever. Magazine staff indicated that many disturbances have taken place in recent years, including the installation of a large oil tank on the southern side of the structure. It appears that the combination of these disturbances and the activities associated with the building's reconstruction have destroyed any evidence of its actual construction date and function.

Chapter 7:

Conclusions

Despite the lack of intact eighteenth-century stratigraphy, the Market Square test excavation did reveal some important information. The series of fortification ditches, for example, suggests a fairly serious effort by the military authorities to protect the arms and powder in the Magazine from perceived and/or real threats. Likewise, the stratigraphic position of these ditches, at least one clearly dated to after 1775 and two others to after the late 1760s, provides evidence that both Structures A and B were built after the ditches were filled, and thus neither could have been the original 1757 market house. Most likely, Structure B was some sort of storehouse or small military structure built between 1770 and 1782, after the northern pair of ditches had been abandoned.

Structure A may well have been the 1835 market house mentioned by Joseph Martin in his Gazetteer. Further investigation will be necessary to determine the architectural details of this building, and perhaps to find some better evidence of early nineteenth-century refuse deposits related to its use.

It appears that little can be learned about the Guard House, since archaeological investigations in 1948 and subsequent reconstruction and repairs have apparently destroyed all stratigraphic patterns and/or associated features. Its true function must remain a mystery unless better documentary evidence can be uncovered.

Testing around Structure E, the very fragmentary building found by James Knight in 1948, revealed relatively intact stratigraphy with an apparent eighteenth-century layer and features including an early posthole. Further investigation in this area may prove fruitful, although much of the building itself has probably been destroyed. In the same way, limited testing inside the Magazine wall revealed refuse-bearing layers that may relate to the use of this area in the eighteenth century.

Finally, further study of undisturbed areas closer to Duke of Gloucester Street may reveal post- or brick-supported buildings previously undiscovered. While the wholesale destruction apparently associated with the razing of the Baptist church in 1934 is discouraging, an intensive testing program may reveal "islands" of intact stratigraphy that can be explored.

Future investigations, then, should concentrate on locating undisturbed stratigraphy north and east of the Magazine, as well as testing the area on the north side of Duke of Gloucester Street east of the Courthouse. Intensive excavation inside the Magazine wall may reveal activity areas, sheds, and refuse deposits that may suggest the use of space in this small area.

Bibliography

- 1781

- Allen's Ordinary through Williamsburg…1781. Samuel DeWill No. 124. Map on file, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1882-1885

- The Official Letters of Governor Spotswood, Lieutenant-Governor of the Colony of Virginia: 1710-1722. Two volumes. William Ellis Jones, Printers, Richmond.

- 1883-1884

- The Official Records of Robert Dinwiddie, Lieutenant-Governor of the Colony of Virginia: 1751-1758. Two volumes. Virginia Historical Society, Richmond.

- 1988

- Distributing Meat and Fish in Eighteenth-Century Virginia: The Documentary Evidence for the Existence of Markets in Early Tidewater Towns. Research Report No. 255. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1988

- Prospectus for Market Square Archaeological Research. Memorandum on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1934

- Archaeological Survey of Foundations Surrounding the Magazine. Map on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1928

- Recollections of Williamsburg as it Appeared at the Beginning of the Civil War, and Just Previous Thereto, with Some Incidents in the Life of its Citizens. Manuscript on file, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1857

- Williamsburg Weekly Gazette, October 7, 1857.

- 1782

- Plan de la ville et environs de Williamsburg en Virginie. Map on file, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg. 30

- 1983

- Town Markets. Manuscript on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1979

- Principles of Archaeological Stratigraphy. Academic Press, London.

- 1823

- The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature in the Year 1619. Thirteen volumes. Samuel Pleasants, Richmond.

- 1755a

- Virginia Gazette, 22 April 1755.

- 1755b

- Virginia Gazette, 5 September 1755.

- 1948

- Archaeological Survey of Foundations of Powder Magazine Guard House, Williamsburg, Virginia, 12C. Map on file, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1986

- The Williamsburg Market House: Where's the Beef? Report for the Educational Planning Group, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Manuscript on file, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1972

- A Manual for the Public Magazine. Manuscript on file, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1928

- Legislative Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia. Three volumes. The Virginia State Library, Richmond.

- 1905

- - 1915 Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1619-1776. Thirteen volumes. The Virginia State Library, Richmond.

- 1835

- A New and Comprehensive Gazetteer of Virginia & the District of Columbia. Charlottesville. 31

- 1797

- The American Gazetteer. Reprinted 1979, The Bookmark, Knightstown, Indiana.

- 1969

- A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

- 1875-1893

- Calendar of Virginia State Papers: 1652-1869. Eleven volumes. The Virginia State Library, Richmond.

- .n.d.

- Governors' Correspondence with the Commissioners for Trade and Plantations, 1708-1714. Public Record Office, CO 5/1314. Microfilm on file, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1768

- Virginia Gazette, 7 September 1768.

- 1985

- Archaeological Briefing and Testing Plan, Block 12, Powder Magazine. Report prepared for the Magazine Interpretive Planning Team. Manuscript on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1788

- Travels in the Confederation, [1783-1784]. Two volumes. Reprinted 1968, Burt Franklin, New York.

- 1893

- A Letter to the Rev. Jedediah Morse, A.M... By a citizen of Williamsburg. Reprinted, William and Mary Quarterly 2(1st series):181-197.

- 1986

- A Prospectus for Magazine Interpretive Research. Memorandum on file, Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1988

- Williamsburg Before and After: The Rebirth of Virginia's Colonial Capital. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

Footnotes

Appendix A:

List of Master Contexts

| M1 | Topsoil |

| M2 | Clean brown loam |

| M3 | Telephone line fill |

| M4 | Telephone line cut |

| M5 | Jimmy Knight trench fills |

| M6 | Jimmy Knight trench cuts |

| M7 | Yellow clay disturbance fill |

| M8 | Yellow clay disturbance cut |

| M9 | Brown mixed layer |

| M10 | Dark brown-yellow mixed layer |

| M11 | Brown-yellow loam |

| M12 | Brown sandy loam |

| M13 | Mottled tan/orange sandy loam with clay pockets |

| M14 | Utility trench fill |

| M15 | Utility trench cut |

| M16 | Brown loam with coal inclusions |

| M17 | Brownish-yellow sandy clay loam |

| M18 | Modern disturbance fill |

| M19 | Modern disturbance cut |

| M20 | Dark brown sandy loam with brick and mortar |

| M21 | Subsoil |

| M22 | Mottled brown soil inside building |

| M23 | Previous archaeology fill |

| M24 | Previous archaeology cut |

| M25 | Layer sealing top brick |

| M26 | Layer inside building sealing builder's trench |

| M27 | Builder's trench fill |

| M28 | Builder's trench cut |

| M30 | Brick wall |

| M31 | Brown loam under brick |

| M32 | Ditch A fill |

| M33 | Ditch A cut |

| M34 | Yellowish-brown sandy clay loam |

| M35 | Subsoil |

| M36 | Ditch B fill |

| M37 | Ditch B cut |

| M38 | Ditch C fill |

| M39 | Ditch C cut |

| M40 | Miscellaneous modern features fills |

| M41 | Miscellaneous modern features cuts |

| M42 | Structural supports for Baptist church |

| M43 | Cuts for structural supports for Baptist church |

| M44 | 1934 archaeology |

| M45 | 1934 archaeology cut |

| M46 | Coal concentration |

| M47 | Northern ditch fill |

| M48 | Northern ditch cut |

| M49 | Southern ditch fill |

| M50 | Southern ditch cut |

| M51 | Miscellaneous modern features fills |

| M52 | Miscellaneous modern features cuts |

| M53 | Coal layer south of Structure A |

| M54 | Posthole fill |

| M55 | Posthole cut |

| M56 | Feature under wall fill |

| M57 | Feature under wall cut |

| M58 | Brown sandy clay loam |

| M59 | Garden features fill |

| M60 | Garden features cut |

| M61 | Brownish-yellow sandy clay loam |

| M62 | Old trench fill |

| M63 | Old trench cut |

| M64 | Whole unit near Structure E |

| M65 | Yellowish-brown silty clay loam |

| M66 | Posthole fill |

| M67 | Posthole cut |

| M68 | Whole unit inside Magazine wall |