A Phase II Archaeological Assessment of the Old Methodist Church Lot

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1663

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

2001

A Phase II Archaeological Assessment

of the Old Methodist Church Lot

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Department of Archaeological Research

P.O. Box 1776

Williamsburg, VA 23187-1776

(757) 220-7330

Katherine W. Schupp

Project Archaeologist

Marley R. Brown III

Principal Investigator

May 2000

Re-issued

April 2001

Management Summary

During the first week of February, 2000, Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Archaeological Research conducted a Phase II archaeological assessment of a small area of land located directly east of the old Methodist Church Lot at the west end of Duke of Gloucester Street. This testing was conducted at the request of Charles Driscoll in response to a proposal to expand Merchants Square's retail space. This assessment was designed to identify the presence or absence of archaeological remains within the area that is being considered for development.

The project area is located within the City of Williamsburg, adjacent to the Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area. The area is located on what Colonial Williamsburg refers to as Block 23 in Colonial Williamsburg's Merchants Square at the far west end of Duke of Gloucester Street. It is bounded to the north and east by the Merchants Square parking lot, to the south by Binn's Department Store, and to the west by the old Methodist Church lot running parallel to North Boundary Street.

The testing consisted of excavating three 75 x 75 cm (2 ½ x 2 ½ foot) test units and three 10-cm (4 inch) auger holes spaced across the testing area at five-meter intervals. All test units and auger holes were investigated to a total depth of 1.5 meters (5 feet). All soil was passed through ¼-inch hardwire mesh screen in order to recover artifacts consistently. All recovered artifacts, except brick and mortar, were retained for laboratory analysis. Detailed descriptions of the stratigraphy recorded the thickness of each soil layer, soil type, and soil color for each test area.

Three test units (500N/500E, 500N/505E, 495N/505E) were investigated to a total depth of 1.5 meters (5 feet). These units consisted of a topsoil layer, a layer of landscaping fill associated with existing shrubs and foliage around the parking lot, and a thick layer of clay fill. The artifacts found in this clay fill consisted solely of architectural debris, including brick, slate, concrete, gravel, asphalt and rebar. This layer appears to have been deposited during the destruction of the old Methodist Church. The units were excavated until this destruction fill was exposed. Then they were augured to determine the depth of the clay fill. In one of the three units, a sterile sand fill was found at a depth of 66 centimeters (2 ½ feet). In the other two units, the bottom of the destruction fill still had not been reached at 1.5 meters (5 feet).

Archaeological deposits in the Historic Area are generally found no deeper than 60 to 80 centimeters (18 to 24 inches) below the ground surface. Due to the extreme depth of disturbance in these units, it was concluded that no intact archaeological deposits survived the demolition of the Methodist Church.

In addition to the three test units, three auger holes (504.5N/505E, 504.5N/510E, 510N/505E) were excavated to determine the extent of the disturbance. All auger holes were excavated to a depth of 1.5 meters (5 feet) and ii shared a similar stratigraphy to the three test units previously excavated. In two of the three auger holes, sterile sand fill was found at an approximate depth of 91 centimeters (3 feet). The remaining auger hole revealed only destruction fill.

Analysis of these soil layers and the artifacts associated with them indicate that the surviving stratigraphy was created during the destruction of the old Methodist Church. No pre-destruction layers were identified. Artifacts included architectural debris associated with this event and modern plastic. Thus, based on the apparent destruction of the eighteenth-century stratigraphy, no further archaeological work is needed.

Table of Contents

| Page | |

| Management Summary | i |

| List of Figures | iv |

| Acknowledgments | v |

| Â | |

| Chapter 1. Introduction | 1 |

| Description of the Project Area | 1 |

| Previous Archaeology | 2 |

| Methods | 3 |

| Chapter 2. Historic Context | 4 |

| European Settlement to Society (1607-1750) | 4 |

| Colony to Nation (1750-1789) | 5 |

| Early National Period (1789-1830) | 5 |

| Antebellum Period (1830-1860) | 5 |

| Civil War (1861-1865) | 6 |

| Reconstruction and Growth (1865-1917) | 6 |

| World War I to Present (1917-1996) | 6 |

| Site Specific Historical Overview | 7 |

| Chapter 3. Results | 10 |

| Chapter 4. Conclusions and Recommendations | 12 |

| Bibliography | 13 |

| Â | |

| Appendix 1. Context List | 15 |

| Appendix 2. Artifact Inventory | 16 |

| Appendix 3. College Corner Phase II Archaeological Assessment, by Jason Boroughs | 17 |

| Page | |

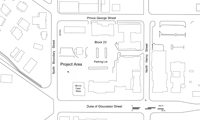

| Figure 1. Project area | 1 |

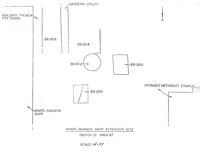

| Figure 2. Archaeological features found during February 1969 excavation | 2 |

| Figure 3. Frenchman's Map (in red) overlaid onto modern Block 23 features | 7 |

| Figure 4. Ca. 1859 photograph of project area | 8 |

| Figure 5. 1904 and 1933 Sanborn maps | 8 |

| Figure 6. College Map, circa 1800 | 9 |

| Figure 7. Project area depicting location of test units and datum point | 10 |

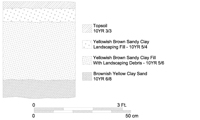

| Figure 8. Typical soil profile for testing area | 11 |

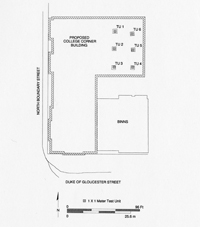

| Figure 9. Location of additional Phase II testing | 18 |

| Figure 10. Features found in Test Unit 1 during additional testing | 19 |

| Figure 11. Profile of Test Unit 1 | 20 |

Acknowledgments

The successful completion of this project was due to the hard work of a number of dedicated individuals. This project was conducted under the general supervision of Dr. Marley R. Brown III, Director of the Department of Archaeological Research at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Staff Archaeologist David Muraca oversaw the project, providing guidance and support. The very experienced field crew consisted of David Brown, Jason Boroughs, Jameson Harwood, and Isabel Jenkins. Donna Sawyers catalogued and processed the artifacts. Jennifer Jones provided very useful historical data from the York County Project files, that data originally synthesized by Heather Wainwright. Heather Harvey prepared the illustrations, and Greg Brown edited and formatted the report.

Chapter 1.

Introduction

At the request of Charles Driscoll, Vice President of Strategic Projects, in February 2000 the property known as the old Methodist Church lot underwent an archaeological assessment in anticipation of the expansion of a portion of the Merchants Square retail space. Previous archaeology conducted in February 1969 revealed intact stratigraphy and features dating to the first quarter of the eighteenth century in an area adjacent to the current project area (Department of Archaeological Research, February 1969). Therefore a Phase II archaeological assessment of the property was conducted in order to determine the extent and integrity of any existing cultural remains.

Work was completed during the first week of February 2000. This project was conducted under the supervision of David Muraca and Dr. Marley Brown III. Katherine Schupp served as project archaeologist and was in charge of the fieldwork and the production of this report.

Description of the Project Area

The project area is located within the City of Williamsburg, adjacent to Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area (Figure 1). The area is located on Block 23, Lots 32

Figure 1. Project area.

2

and 33, in Colonial Williamsburg's Merchants Square at the far west end of Duke of Gloucester Street. It is bounded to the north and east by the Merchants Square parking lot, to the south by Binn's of Williamsburg Department Store, and to the west by North Boundary Street.

Figure 1. Project area.

2

and 33, in Colonial Williamsburg's Merchants Square at the far west end of Duke of Gloucester Street. It is bounded to the north and east by the Merchants Square parking lot, to the south by Binn's of Williamsburg Department Store, and to the west by North Boundary Street.

Excavation was concentrated on the northeast section of the lot for a number of reasons. First, archaeological testing had already taken place in the southeastern section of the lot in February 1969. This testing found intact eighteenth-century stratigraphy and features before they were destroyed by the construction of a west addition to Binn's of Williamsburg (Department of Archaeological Research, February 1969), but as this area was covered at this time, no further archaeological testing is needed. Second, photographs of the church indicate that the building covered the west side of the block and extended up to the south and west sidewalks (Block and Building Files), and construction of the church undoubtedly destroyed any archaeological deposits in this part of the block. Archaeological monitoring of the destruction of the old Methodist Church in March 1981 confirmed the lack of any significant archaeological remains underneath the church (Department of Archaeological Research, March 1981). Therefore, the only remaining area in this lot that might contain intact archaeological remains was the northeast section.

Previous Archaeology

On February 24, 1969 rescue archaeology was conducted in a small area located between Binn's of Williamsburg and the Methodist Church building (Figure 2). The area had been graded by machinery in order to begin construction of a basement

Figure 2. Archaeological features found during February 1969 excavation.

3

addition to the store. A series of round and rectangular pits, all containing ash, were found, as well as part of a cellar that had been filled before the 1730s. A large number of eighteenth-century artifacts were found, including tin-glazed earthenware cups, a delftware salt, cutlery, tobacco pipes, and fragments of bottles (Department of Archaeological Research, February 1969).

Figure 2. Archaeological features found during February 1969 excavation.

3

addition to the store. A series of round and rectangular pits, all containing ash, were found, as well as part of a cellar that had been filled before the 1730s. A large number of eighteenth-century artifacts were found, including tin-glazed earthenware cups, a delftware salt, cutlery, tobacco pipes, and fragments of bottles (Department of Archaeological Research, February 1969).

Additional archaeological monitoring was conducted several times at this site in March 1981 during the destruction of the Methodist Church building. Archaeologists looked for evidence of earlier buildings and artifacts that would pre-date the church. The earliest material culture found dated to the mid-nineteenth century, but no structural remains were discovered (Department of Archaeological Research, March 1981).

Methods

The testing consisted of excavating three 75 x 75 cm (2 ½ x 2 ½ foot) units and three 10-cm (4-inch) auger holes. These holes were placed across the testing area at five-meter intervals. A grid imposed upon the testing area determined the location of these units. The datum point for this coordinate system was located to the northwest of Binn's of Williamsburg.

All units were stratigraphically excavated by hand to a depth of 1.5 meters (5 feet) using a variety of tools including shovels, trowels and an auger. Coordinates and context numbers were assigned to each test unit so that soil layers could be systematically recorded. All measurements were metric, following standard recording practices for the department.

All soil was screened through ¼-inch hardwire mesh screen in order to consistently recover artifacts. These artifacts were sent to the laboratory for analysis and storage, with the exception of modern architectural material. A representative sample of this material was saved; the rest of it was noted in the site's context records. Appendix 2 gives a complete list of recovered artifacts.

Chapter 2.

Historic Context

The project area is located in Virginia's Northern Coastal Plain region, an area rich in both prehistoric and historic sites. This site is located within the boundary of the colonial town of Williamsburg.

European Settlement to Society (1607-1750)

The earliest known European settlement in the vicinity of the project area was during the third and forth decades of the seventeenth century. In 1632 the House of Burgesses passed the "Act for Seating of the Middle Plantation" (Hening 1969), which called for the building of a palisade between the James and York Rivers, across what is today the City of Williamsburg. Two sections of this palisade were found-one during a Phase I survey of the proposed Second Street extension (Hunter et al. 1985) and another during the survey of the Bruton Heights School property (Muraca et al. 1992).

During the subsequent decades of the seventeenth century, Middle Plantation grew in population and importance. By 1676 Middle Plantation was considered consequential enough for Nathaniel Bacon to launch his rebellion there (Goodwin 1959). By 1693 it was important enough to be selected as the location for Virginia's first college, the College of William & Mary. By the time the General Assembly was seriously considering moving the capital there, Middle Plantation contained "a church, an ordinary, several stores, two mills, a smith's shop, a grammar school, and above all the Colledge" (reprinted in Anonymous 1930: 323-337).

In 1699 Theodorick Bland was ordered by the General Assembly to survey and lay out the new town of Williamsburg at the existing settlement of Middle Plantation. The purpose of the survey was to establish the boundaries of a new capital city for Virginia. Along with the town, two ports were included in the plan, one at Archer's Hope Creek, later known as College Creek, connecting the new city to the James River, and another at Queen's Creek, connecting the city to the York River and to Yorktown, a deep water port town established in 1691 that became Williamsburg's seaport.

Although Williamsburg was firmly established as the capital of the Virginia Colony during the first half of the eighteenth century, it remained small, with a permanent population of about 1500. As the capital, it grew enormously, if temporarily, twice yearly, during "Publick Times" when the General Assembly was in session. In spite of the growth of Williamsburg and Yorktown as commercial and cultural centers, the majority of the population remained rural throughout this period.

Colony to Nation (1750-1789)

By the mid-eighteenth century, the capital of Virginia, the largest and most prosperous English American colony, had established itself as a viable and diverse community and cultural center, although it never came to rival New York, Boston, or Philadelphia because of the rural nature of Virginia's economy. During this period, Williamsburg had a continuously operating theatre, a college, the colonies' first asylum for the insane, a host of craft industries, and taverns. The population of the town remained small, except during the great influx of people during the "Publick Times." Leaders in the move toward revolution (such as Peyton Randolph, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington) were members of the General Assembly, lived in Williamsburg, or frequently had reason to be there, making this period the most influential and exciting in Williamsburg's history.

Early National Period (1789-1830)

The effects of moving the capital from Williamsburg to Richmond in 1780 became evident in the years following the revolution. Williamsburg, and the Tidewater in general, fell into economic decline as the population and influence centers moved westward. The surrounding counties continued their agrarian orientation and the rotation of wheat and corn crops (Rochefaucauld 1799). The short-lived boom of wheat production declined sharply after the war in and with Europe came to an end. This was helped along by insect ravages and the poor quality of soil in the over-farmed Tidewater (Brown et al. 1986).

Antebellum Period (1830-1860)

During this period, agriculture continued to be the predominant economic activity in the area. Some improvement in the soil's ability to grow crops was initiated by Edmund Ruffin. Ruffin discovered that marl, a naturally-occurring outcrop of Miocene fossil shell, could be mixed with soil to mitigate its innate acidity, allowing better growing potential. Marl was an inexpensive and readily available commodity throughout the area. By 1840, wheat and corn production was up some 200% (Bruce 1932).

Industry in the mid-nineteenth century Williamsburg area included five dry goods stores, eight lumber yards, one tannery, two grist mills, a carriage manufactory, and a furniture shop. By 1860 there were fourteen mills in the area, eleven in James City and three in York County (Brown et al. 1986).

Williamsburg in 1835 consisted of 200 houses in addition to a new market house, sixteen stores, a manufactory, four mills, three tanyards, and a saddler's shop. In 1855 a new courthouse and two Baptist churches were under construction in the city (Carson 1961).

During the early nineteenth century several free black communities were established in the Williamsburg area. The most notable was Centerville, located in James City County, several miles northwest of the city. By 1850 nearly 400 free African Americans lived around Centerville, gainfully employed in agriculture and craft-related industries.

6By the outbreak of the Civil War, the Williamsburg area was recovering from the economic set-backs of the late eighteenth century, both agriculturally and industrially, becoming a viable entity in Tidewater Virginia once again.

Civil War (1861-1865)

Williamsburg again became a center of activity during the first half of the Civil War as an enemy-occupied town during the Peninsula Campaign. Although no known fortifications existed within a kilometer of the project area, Fort Magruder and associated earthworks are located about three kilometers (1.8 miles) to the south.

Reconstruction and Growth (1865-1917)

The James City, York County, Williamsburg area recovered slowly from the effects of the Civil War. Agriculture was still the basis of the economy, but the lack of slave labor change farming practices. A large population of free blacks remained in the area, serving again as laborers on farms. While other parts of the country were experiencing a rise in industrialization, this area remained strongly agrarian. Large plantations were broken up into smaller farms, some owned by the slaves that once attended them (Brown et al. 1986).

The advent of the railroad in 1881 as an efficient method of transporting both people and commodities began to help the area out of its economic slumber, but not until well into the twentieth century. Unfortunately, highways fell into disrepair, probably into a worse state than they were in during the first part of the eighteenth century. The steamship also saw its rise in this period with regular stops in West Point, Williamsburg, Newport News, and Norfolk.

It should also be noted that the early preservation movement (which was to become so important to the Williamsburg area in the next period) began with activities centered around the tercentenary of the establishment of Jamestown. The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities was founded in 1889, the College of William & Mary was re-opened in 1888, President Roosevelt called national attention to Jamestown in 1907, and the Reverend W.A.R. Goodwin restored Bruton Parish Church in 1907.

World War I to Present (1917-1996)

The Williamsburg area remained largely dependent economically on farming well into the twentieth century. In the late 1920s new industries were established that would forever change the economic landscape of the Williamsburg area, historic preservation and tourism. The restoration of Virginia's second capital through the efforts of W.A.R. Goodwin and John D. Rockefeller succeeded in bringing the area out of its economic rut, causing a great deal of growth in a relatively short time. Within the last 30 years, the small farm has all but disappeared from the landscape, being replaced by shopping centers, outlet malls, and housing developments. Tourism has become the major source of income in the area. Other industries in the Williamsburg area include beer manufacturing, glass making, fibers, and a winery.

Site Specific Historical Overview

Little attention had been paid to the history of Block 23 until recently. According to the "Frenchman's" Map of circa 1782 (Figure 3), there was a line of buildings fronting Duke of Gloucester Street, but very little development on the land surrounding them. Specifically, two buildings are shown in the project area. One falls on lot 32, and the other on lot 33. Nineteenth-century ownership is unknown for these two lots until the 1930s, with the construction of the Methodist Church and the development of Merchants Square.

Lot 32

The documented history of lot 32 begins in 1712 when William Craig acquired the property and made improvements upon it. He operated a tavern on this site until his death somewhere between June 1719 and June 1720. As a stipulation of his will, this lot and its buildings were divided along a north-south line with ownership split between his two daughters, Elizabeth and Edith. Documents reference a dwelling house on the western half of the lot as well as additional outbuildings scattered throughout the entire property.

The western half of the lot, owned by Elizabeth and her husband James Gambell, was sold and mortgaged a number of times between 1720 (at the earliest) and 1751. Owners and mortgagors included Charles and Mary Lewis, merchants John Harmer and Walter King. By 1751, Sarah Packe owned the property and

Figure 3. Frenchman's Map (in red) overlaid onto modern Block 23 features.

8

sold it to David Middleton, for ¬30 Virginia currency, signaling that the main dwelling house on the property was either small or in disrepair (Jennifer Jones, 2000). Middleton resided on the property until his death circa 1800 (Goodwin 1950: 3). It is unclear as to what happened to the eastern half of the lot owned by Edith.

Figure 3. Frenchman's Map (in red) overlaid onto modern Block 23 features.

8

sold it to David Middleton, for ¬30 Virginia currency, signaling that the main dwelling house on the property was either small or in disrepair (Jennifer Jones, 2000). Middleton resided on the property until his death circa 1800 (Goodwin 1950: 3). It is unclear as to what happened to the eastern half of the lot owned by Edith.

In an oral history entitled Recollections of Williamsburg, one of the last survivors of Civil War-era Williamsburg, John S. Charles, describes his memories of the town in the 1860s. He notes that there was a two story frame house on the lot predating the construction of the Methodist Church. A circa 1859 photograph (Figure 4) confirms this description, as do the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of 1904, 1910 and 1921 (Figure 5). These maps indicate the presence of four buildings on the property until 1910, and three buildings as of 1921. In 1933, all of these buildings were replaced by three new structures, one of which was the Methodist Church, which stood until 1981.

Lot 33

The history of lot 33 is incomplete. The first documented record concerning this property is in 1719 when John Holloway acquired the property from the city. Holloway eventually became the mayor, burgess, Speaker and Treasurer for

Figure 4. Ca. 1859 photograph of project area.

Figure 4. Ca. 1859 photograph of project area.

Figure 5. 1904 and 1933 Sanborn maps.

9

Williamsburg (Goodwin 1950: 3). The circa 1800 "College" Map (Figure 6) shows that this lot was owned by a person named Meade at that time. The next documented owner is also in 1800, when Priscilla and Caleb Spann sold the lot to Josiah Davis (Goodwin 1950: 3).

Figure 5. 1904 and 1933 Sanborn maps.

9

Williamsburg (Goodwin 1950: 3). The circa 1800 "College" Map (Figure 6) shows that this lot was owned by a person named Meade at that time. The next documented owner is also in 1800, when Priscilla and Caleb Spann sold the lot to Josiah Davis (Goodwin 1950: 3).

According to the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of 1904 and 1910 there were two buildings on the property, with a garage added by 1921. By 1933, these buildings were torn down and replaced by Merchants Square.

Figure 6. College Map, ca. 1800.

Figure 6. College Map, ca. 1800.

Chapter 3.

Results

Six test units were investigated to a total depth of 1.5 meters (5 feet) (Figure 7). Archaeological deposits in the Historic Area are generally found no deeper than 60 to 80 centimeters (18 to 24 inches) below the ground surface. Due to the extreme depth of these units, it was concluded that no intact archaeological deposits survived the demolition of the Methodist Church.

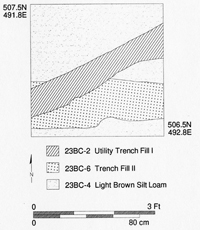

What exists today are at least three to four layers of modern fill that were deposited throughout the twentieth century, primarily associated with the destruction of the Methodist Church building (Figure 8). All units contained topsoil, measuring from 4 to 10 cm (1.5 to 4 inches), consisting of a very dark grayish brown (Munsell color 10YR3/2) sandy loam containing a few modern artifacts. Below topsoil was a layer of landscaping fill associated with the existing shrubs and foliage around the parking lot. This layer measured 10 to 20 centimeters (4 to 8 inches) in depth and consisted of yellowish brown (10YR5/4) sandy clay containing a few modern artifacts. The third common layer was destruction fill containing a significant amount of architectural debris, including brick, slate, concrete, gravel, asphalt and rebar. This layer, a yellowish brown (10YR5/6) sandy clay, ranged from 60 to 64 centimeters (2 to 2 ½ feet) deep in some units and was 64+ centimeters (2 ½ + feet) in others. The fourth layer, a brownish yellow (10YR6/8) sandy clay fill, was found in half of the units and was at least 68+ centimeters (2 ¼ + feet) deep. It contained no artifacts.

Figure 7. Project area depicting location of test units.

Figure 7. Project area depicting location of test units.

Figure 8. Typical profile for testing area.

Figure 8. Typical profile for testing area.

Three test units (500N/500E, 500N/505E, and 495N/505E) were investigated to a total depth of 1.5 meters (5 feet). These units consisted of the first three layers described above: topsoil, landscaping fill, and destruction fill. They were excavated using shovels until the destruction fill was exposed. Then they were augured to determine the depth of the fill. In one of the three units (500N/500E), the sterile sand fill was found at a depth of 66 centimeters (2 ½ feet) below the ground surface. In the other two units, the bottom of the destruction fill still had not been reached at 1.5 meters (5 feet).

In addition to the three test units, three 10-cm (4-inch) auger holes (504.5N/505E, 504.5N/510E, and 510N/505E) were excavated to determine the extent of the disturbance associated with the destruction of the Methodist Church. All auger holes were excavated to a depth of 1.5 meters (5 feet) and shared similar stratigraphy to the three test units. In two of the three auger holes (504.5N/505E, 510N/505E), sterile sand fill was found at an approximate depth of 91 centimeters (3 feet) below the ground surface. The remaining auger hole revealed only destruction fill.

Chapter 4.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The Phase II assessment of the northeast quadrant of Block 23, Lot 32 identified no intact archaeological remains. This area seems to have been completely disturbed during the destruction of the old Methodist Church building and during construction of additions to Binn's of Williamsburg. Therefore, no further archaeological work is recommended.

Bibliography

- 1930

- Speeches of Students of the College of William and Mary Delivered May 1, 1699. William & Mary Quarterly 10 (2nd series): 323-337.

- n.d.

- Box 57, Block 23, Building 1 - Block 27. Special Collections, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1986

- Toward a Resource Protection Process: James City County, York County, City of Poquoson, and the City of Williamsburg. Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1932

- Virginia Agricultural Decline to 1860: A Fallacy. Agricultural History 6:3-13.

- 1961

- We Were There: Descriptions of Williamsburg, 1699-1859. Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1932

- Recollections of Williamsburg: As It Appeared at the Beginning of the Civil War and Just Previously Thereto, With Some Incidents in the Life of its Citizens. Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller Jr Library, Williamsburg.

- 1969

- Monthly Report on Archaeological Activities, February 1969. Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1981

- Monthly Report on Archaeological Activities, March 1981. Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1782

- Plan de la Ville et Environs de Williamsburg en Virginia, 1782. Photostat on file. Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller Jr Library, Williamsburg.

- 1950

- Blocks 15, 14 (South) & 23, 22 (North) Historical Report, Block 15. Originally Entitled: "Duke of Gloucester Street - Present Business Area BLocks 15, 14 (South); & 23, 22 North". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Report Series 1314. John D. Rockefeller Jr Library, Williamsburg. 14

- 1951

- A Brief and True Report Concerning Williamsburg in Virginia. Deitz Press, Richmond.

- 1809-1823

- The Statues at Large: Being a Collection of All Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619. Reprinted 1969. 13 vols. Franklin Press, Richmond.

- 1985

- Phase I Archaeological Testing of the Proposed Second Street Extension, York County and Williamsburg, Virginia. Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 2000

- Personal communication.

- 1992

- Archaeological Testing at Bruton Heights. Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1799

- Travel Through the United States of North America...in the Years 1795, 1796, 1797. Vol. II, London.

- 1904

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, Williamsburg, James City County, Virginia. New York.

- 1910

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, Williamsburg, James City County, Virginia. New York.

- 1921

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, Williamsburg, James City County, Virginia. New York.

- 1933

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, Williamsburg, James City County, Virginia. New York.

- 1807

- Williamsburg, the Old Colonial Capitol. Photostat on file, John D. Rockefeller Jr Library, Williamsburg.

Appendix 1.

Context List

| Context | Test Unit | Layer |

|---|---|---|

| 23BB-1 | 1 | TOPSOIL |

| 23BB-2 | 1 | SANDY CLAY LANDSCAPING FILL |

| 23BB-3 | 1 | YELLOW-ORANGE SANDY CLAY FILL |

| 23BB-4 | 2 | TOPSOIL |

| 23BB-5 | 2 | SANDY CLAY LANDSCAPING FILL |

| 23BB-6 | 2 | YELLOW-ORANGE SANDY CLAY FILL |

| 23BB-7 | 1 | SAND FILL |

| 23BB-8 | 2 | SAND FILL |

| 23BB-9 | 3 | TOPSOIL |

| 23BB-10 | 3 | SANDY CLAY LANDSCAPING FILL |

| 23BB-11 | 3 | YELLOW-ORANGE SANDY CLAY FILL |

| 23BB-12 | 4 | AUGERED TEST UNIT #4 |

| 23BB-13 | 5 | AUGERED TEST UNIT #5 |

| 23BB-14 | 6 | AUGERED TEST UNIT #6 |

Appendix 2.

Artifact Inventory

| AA | 1 | OTHER INORGANIC, CEMENT, PORTLAND |

| AB | 1 | IRON ALLOY, NAIL, LESS THAN 2 IN, WROUGHT/FORGED |

| AA | 1 | GLASS, CLRLESS NON-LD, FRAGMENT, BEER/POP BOTTLE, MACHINE-MADE, LETTERING/NUMB, indeterminable, HOBBLE NECK |

| AA | 1 | OTHER INORGANIC, CEMENT, PORTLAND |

Note: Inventory is printed from the Re:discovery cataloguing program used by Colonial Williamsburg, manufactured and sold by Re:discovery Software, Charlottesville, Virginia. Brief explanation of terms:

| Context No. | Arbitrary designation for a particular deposit (layer or feature), consisting of a four-digit "site/area" designation and a five-digit context designation. The site/area for this project is "23BB." |

| TPQ | "Date after which" the layer or feature was deposited, based on the artifact with the latest initial manufacture date. Deposits without a diagnostic artifact have the designation "NDA," or no date available. |

| Listing | The individual artifact listing includes the catalog "line designation," followed by the number of fragments or pieces, followed by the description. |

Appendix 3.

College Corner Phase II Archaeological Assessment (Block 23), by Jason Boroughs

Introduction

After the original Phase II archaeological study was completed, the design of the College Corner Building changed, with the new plan calling for construction outside the area originally tested. In order to assess this expanded area of construction addition Phase II study was undertaken.

During the first week of April 2001, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Archaeological Research (D.A.R.) conducted a Phase II archaeological assessment of a 10 x 20 meter section of parking lot located within Colonial Williamsburg's Merchant's Square. An archaeological investigation was conducted in anticipation of a proposed expansion of the Merchant's Square retail space. The archaeological assessment consisted of the hand excavation, by stratigraphic layer, of six 1 x 1 meter test units in the southwest corner of the Merchant's Square parking lot. The test units were strategically placed in order to test for the presence or absence of historic deposits or features that would be destroyed by the expansion of the Merchant's Square retail space. The Phase II investigation discovered intact stratigraphy in only one of the six test units. The absence of intact stratigraphic layers in the remaining five test units is due to the presence of modern intrusions that are most likely associated with the construction of the parking lot.

Project Area and Previous Archaeology

The project area lies within a small parcel of land at the convergence of Duke of Gloucester and North Boundary streets on Block 23 of the Colonial Williamsburg Historic Area. The block is currently home to Colonial Williamsburg's Merchant's Square, a retail complex consisting of shops and restaurants catering primarily to college students and visitors to the Historic Area. The project area encompasses a 10 x 20 meter plot in the southwest corner of the Merchant's Square parking lot, bordering retailers to the north and south and adjacent to the Old Methodist Church lot on the east. The area to be investigated appears to fall primarily within colonial lot 33, but may extend to the east and west into adjacent lots 32 and 34 as well.

D.A.R. archaeologists conducted a Phase II archaeological assessment of the Old Methodist Church lot during the winter of 2000 and concluded that the surviving stratigraphic deposits were most likely either associated with the destruction of the Methodist Church in 1981 or with other modern activity on Block 23 (see the main body of this report). No pre-destruction deposits were identified and therefore no further archaeological investigations were recommended.

Research Design and Methods

Prior to the arrival of the archaeological field crew, six 1.5-meter-square sections of asphalt paving were removed from the southwest corner of the Merchant's Square parking lot to facilitate archaeological testing of the property. A metric grid was then established and six 1 x 1 meter test units were strategically placed in two parallel north-south transects of three each at five to six meter intervals (Figure 9). All test units were stratigraphically excavated by shovel and trowel to sterile subsoil. Each soil layer was assigned a unique context number and detailed descriptions of each stratigraphic component were systematically recorded. Excavated soils were passed through ¼-inch mesh screen and recovered cultural and faunal materials were retained for laboratory analysis. All artifacts were washed, inventoried, and catalogued and are currently housed at the D.A.R. laboratory facility.

2001 Phase II Assessment Results

Of the six test units excavated during the Phase II assessment, Test Unit 1 yielded the only intact stratigraphic sequence containing evidence of colonial occupation.

Figure 9. Location of additional Phase II testing.

19

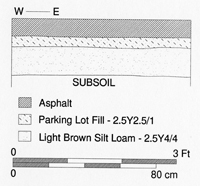

Once the asphalt paving was removed, a related stratum of parking lot fill, consisting basically of crushed asphalt and sand, was removed by shovel to expose a layer of olive brown silty loam. Test Unit 1 contained two modern linear trenches that intruded into the olive brown silty loam (Figure 10). The first contained a fill of mottled dark grayish brown sandy loam with several small concentrations of marl. Trench 1, 30 centimeters in width, was cored with a small auger to a depth of approximately 25 centimeters, at which point subsoil was not reached. The second trench, 15-20 centimeters in width, cut through Trench 1 as well as the layer of olive brown silty loam and contained a fill of mottled yellow and gray clays. Trench 2 was cored as well and the fill continued below a depth of 25 centimeters. A section of olive brown silty loam not impacted by Trenches 1 and 2 was excavated and found to rest atop sterile subsoil at a depth of 16 centimeters. The layer contained a number of artifacts dating from the mid to late eighteenth century, including refined ceramics, glass, iron nails, and clay smoking pipe fragments. Trenches 1 and 2 were not excavated as they continued below the level of subsoil exposed beneath the layer of olive brown silty loam.

Figure 9. Location of additional Phase II testing.

19

Once the asphalt paving was removed, a related stratum of parking lot fill, consisting basically of crushed asphalt and sand, was removed by shovel to expose a layer of olive brown silty loam. Test Unit 1 contained two modern linear trenches that intruded into the olive brown silty loam (Figure 10). The first contained a fill of mottled dark grayish brown sandy loam with several small concentrations of marl. Trench 1, 30 centimeters in width, was cored with a small auger to a depth of approximately 25 centimeters, at which point subsoil was not reached. The second trench, 15-20 centimeters in width, cut through Trench 1 as well as the layer of olive brown silty loam and contained a fill of mottled yellow and gray clays. Trench 2 was cored as well and the fill continued below a depth of 25 centimeters. A section of olive brown silty loam not impacted by Trenches 1 and 2 was excavated and found to rest atop sterile subsoil at a depth of 16 centimeters. The layer contained a number of artifacts dating from the mid to late eighteenth century, including refined ceramics, glass, iron nails, and clay smoking pipe fragments. Trenches 1 and 2 were not excavated as they continued below the level of subsoil exposed beneath the layer of olive brown silty loam.

Test Units 2, 4, 5, and 6 each contained a layer of loose asphalt and gravel in a matrix of sandy loam that lay above sterile subsoil. The fill is most likely related to the twentieth century construction of the parking lot. At the eastern edge of Test Unit 4, excavation revealed evidence of an earlier concrete parking lot with embedded cut stone cobbles. It appears as if the area west of the earlier parking lot may have been graded and covered with fill in order to create a level paving surface, and in so doing, any pre-existing stratigraphic sequences were ultimately destroyed.

Figure 10. Features found in Test Unit 1 during additional testing.

Figure 10. Features found in Test Unit 1 during additional testing.

Figure 11. Profile of Test Unit 1.

Figure 11. Profile of Test Unit 1.

Archaeologists exposed a large circular modern feature in Test Unit 3 that cut through a section of fill similar to the layer of loose asphalt and gravel discovered in Test Units 2, 4, 5, and 6. The asphalt fill was excavated to subsoil at a depth of 15 centimeters. A section of the modern disturbance was excavated and cored with a small auger and found to continue to at least a depth of 45 centimeters.

Conclusions

Positive evidence of colonial-period occupation was discovered in only one of six test units excavated in the project area during the Phase II assessment. The absence of intact stratigraphic layers in the remaining five test units is most likely due to the twentieth-century parking lot construction and expansion campaigns in the Merchant's Square retail complex. Based upon the findings of the 2001 Phase II archaeological assessment, no further archaeological investigation within the impact area is recommended.