Cross-Section Microscopy Analysis of Interior Paints — William Finnie House (Block 2, Building 7)Cross-section Microscopy Analysis Report: Finnie House Interior (Block 2, Building 7)

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1743

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2013

CROSS-SECTION MICROSCOPY ANALYSIS REPORT

Finnie House Interior

Block 2, Building 7

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION

WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA

Table of Contents

| Purpose | 3 |

| History | 3 |

| Previous Color Research | 4 |

| Procedures | 5 |

| Results | 6 |

| First floor, west room | 7 |

| First floor, front passage | 26 |

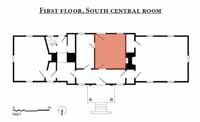

| First floor, south (rear) central room | 37 |

| First floor, east room | 43 |

| First floor, east passage | 50 |

| First floor, staircase | 58 |

| Second floor, passage | 66 |

| Second floor, northwest room | 76 |

| Second floor, present bathroom | 84 |

| Second floor, present south room | 87 |

| Fluorochrome staining results | 92 |

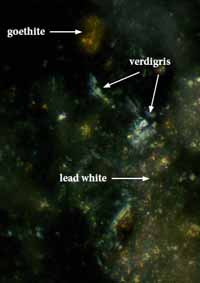

| Pigment identification results | 100 |

| Color measurement results | 107 |

| Conclusions | 114 |

| References | 115 |

| Appendix A. Samples and sample locations | 116 |

| Appendix B. Procedures | 119 |

| Appendix C. Sample memoranda: March 3, 2001 | 122 |

| Appendix D. Sample memoranda: March 11, 2011 | 125 |

| Appendix E. Sample memoranda: March 29, 2011 | 127 |

| Appendix F. Sample memoranda: April 21, 2011 | 129 |

Finnie House: Block 2, Building 7, north elevation

Finnie House: Block 2, Building 7, north elevation

| Structure: | Finnie House, Block 2, Building 7 |

|---|---|

| Requested by: | Edward Chappell, Roberts Director of Architectural and Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation |

| Analyzed by: | Kirsten Travers, Graduate Fellow, Winterthur / University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation |

| Consulted: | Susan L. Buck, PhD., Conservator and Paint Analyst, Williamsburg, Virginia |

| Date submitted: | June 2011 |

Purpose:

The goal of this project is to use cross-section microscopy techniques to explore the early finish history of the Finnie House, particularly to determine if all of the woodwork was painted the same color in the first period or if a variety of colors were used throughout the interior. In some cases, comparative paint chronologies were used to determine which elements were original to the house, in particular the mantel in the central block.

History:

The structure currently known as the Finnie House is one of the most formal late colonial houses in Williamsburg. It is a wood-frame, weatherboarded house in the tripartite "temple-form" Palladian style with a two-story pedimented central block (the tympanum of which contains a circular window), flanked by two one-story gable-roofed wings projecting to the east and west. In a letter dated 1809, St. George Tucker described it as "the handsomest house in town" (Whiffen 1984, 228).

The exact date of construction is unknown, but some records suggest it was built between 1772-1778 by William Pasteur, a physician and apothecary in Williamsburg (Stephenson 1964, 5-10). An elongated structure resembling the house appears on the Frenchman's Map of 1782, providing a terminus ante quem for the house. Less than twenty years later, a sketch of the house on an insurance policy dated July 20, 1801 made out for James Semple, a judge and professor of law at the College of William and Mary, shows it in much the same condition as it appears today.

The original ground-floor arrangement included a square central hall flanked by a large, formal room to the west and a smaller room, passage, and stair hall to the east. A winding stair in the south (rear) end of the building provided access to the second floor, where a passage and two chambers occupied the space above the central block. The ground floor plan of the Finnie House is strikingly similar to a sketch made by Thomas Jefferson in 1771, when he lived in Williamsburg (Kocher and Dearstyne 1950, 7-8). The sketch, an early plan for his Monticello estate, consists of a large central hall flanked by smaller wings of equal size. Many of the dimensions correspond precisely with the Finnie House. This evidence, in conjunction with the fact that Jefferson was one of the leading proponents of classical "temple-form" architecture 4 of the new republic, and that he had familial and professional connections with William Pasteur, has lead some scholars to suggest that the Finnie House was designed by him (Askins 1972, 40-51).

The interior retains almost all of its original, high-quality woodwork including cornices, flush paneled wainscot and 8-paneled door leaves on the first floor, and bolection moldings on both floors. The woodwork in the first-floor west room is the most elaborate and includes a full modillion cornice and an elaborate mantel with diaper-patterned fretwork on the frieze. Some suggest that cabinetmaker Benjamin Bucktrout (1744-1812), was responsible for the fine interior woodwork. Bucktrout emigrated to Williamsburg from England in 1766, and had a shop adjacent to the Semple property on Francis street (Kocher and Dearstyne 1950, 30), but evidence connecting him to the Finnie House is merely circumstantial.

The house was acquired by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 1928 and restoration was carried out from January — December 1932. Restoration work was conservative and repairs or replacements carried out only where necessary. During this period the south wing, believed to be an early 19th-century addition (c.1806-1823), was removed, as was a non-original partition wall dividing the central block into two spaces (the front passage and center room). Some time later, more partitions were added dividing the central block into the present front passage, kitchen, and south central room. The second floor has also been altered significantly from its original arrangement. A seam in the flooring in the present south room suggests that this transverse partition was moved about 4 feet to the east (Chappell 2011, memorandum), and other partitions have been moved from their original locations resulting in a completely new arrangement (Kocher and Dearstyne 1950, 50), including a modern bathroom. Despite this change, much of the second-floor trim is original, but the mantels are new and some of the door leaves have been moved from their original locations.

In contrast to the abundance of original woodwork, all of the original plaster was removed during the restoration as it was "in such disrepair that it could not be reused." (Kocher and Dearstyne 1950, 29) .

Previous Color Research:

During the restoration, crude paint scrapes were used to investigate the original colors. In a letter dated February 9, 1932, Harold R. Shurtleff wrote to architects Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn:

"We have scraped the paint on the old work at the above building [Finnie House]. There is usually a coat of Spanish brown next to the wood, which we assume is a priming coat. On top of the paint colors scheduled herein are frequently other colors, some very attractive. There follows the schedule of colors which we believe are the original ones…" (Kocher and Dearstyne 1950, 59).

| Room | Woodwork | Walls |

|---|---|---|

| entrance hall #2 | sage green (#65W) | white (#125S approx.) |

| living room #1 | greenish, white (tinted white, only one color #38 tinted up) | white (#125 S approx.) |

| bed room #2 | ochre ivory (#93S) | #40 lightened with white only |

| stairway and hall adjoins on 1st and 2nd floor- newel and balusters, etc. | ochre ivory (#93S) | whitewash |

| dining room | gray (#37W) | white |

Procedures:

Sixty-two samples were collected on four separate occasions from the interior of the Finnie House. On March 3, 2011, Kirsten Travers and Edward Chappell collected twenty-nine paint samples from various interior spaces on the first-floor, in particular the west room, the front passage, and the south (rear) central room. On March 11, 2001, Travers and Chappell returned to the house to collect fourteen samples from the east first-floor passage, staircase, and the east first-floor room. On March 29, 2011 fourteen additional samples were taken from the second-floor spaces including the rooms and passage. On April 21, 2011, Travers returned to collect five samples from the first and second-floor passages.

On site, a monocular 30x microscope was used to examine the painted surfaces and determine the most appropriate areas for sampling. A microscalpel was used to remove the samples, which were labeled and stored in small individual Ziploc bags for transport. All samples were given the prefix "FH" and numbered according to the order in which they were collected.

In the laboratory, the samples were examined with a stereomicroscope under low power magnification (5x to 50x), to identify those that contained the most intact paint evidence and would therefore be the best candidates for cross-section microscopy. Uncast sample portions were retained for future examination and analysis. The best candidates were cast in resin cubes and sanded and polished to expose the cross-section surface for microscopic examination.

Once cast, the cross-section samples were examined and digitally photographed in reflected visible and ultraviolet light conditions at 20x to 400x magnifications. By comparing the resulting photomicrographs, finish generations could be interpreted based on physical characteristics such as color, texture, thickness, presence of dirt layers and extent of surface deterioration. Fluorochrome staining was also carried out on selected samples to characterize the types of binding media present (oils, carbohydrates, proteins). The most informative photomicrographs and their corresponding annotations, as well as comments from the author, are contained in the body of this report. All raw photomicrographs can be found in the Appendix.

Results:

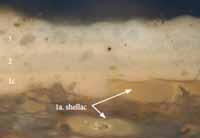

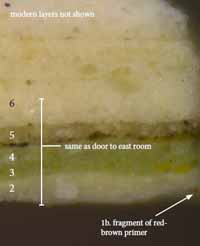

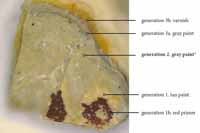

The original woodwork in the Finnie House retains a great deal of intact paint evidence from which the earliest decorative schemes can be postulated. The data indicates that in the first generation, almost all of the woodwork in the house was sealed with shellac, primed with a thin red-brown layer, and painted a tan color. This tan-colored paint was made with white lead and large, coarsely ground particles of yellow ochre. This first period tan color was found throughout the house, including the first and second floors. In the second generation, most elements were repainted the tan color. Little time appears to have elapsed between the first and second generations, but enough samples contained a distinct paint boundary to identify them as separate layers.

In the third generation, more color variation was seen in the house, including a pale blue in the first-floor west room, an olive-green on the woodwork in the central block and passages, and gray in the east room. The staircase newel was olive-green while the balusters and stringers were red-brown, and the second-floor trim was painted a deep green color made with verdigris while the door leaves were red-brown. It is interesting to note that in this period, the first-floor door leaves and architraves were the same color, but contrasting colors were used on the leaves and trim upstairs. A color scheme consisting of contrasting leaves and trim was not used on the lower floors until generation 5, when the leaves were painted red-brown and the trim was a resinous light brown color.

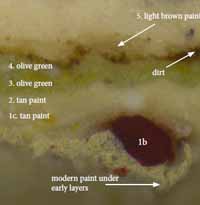

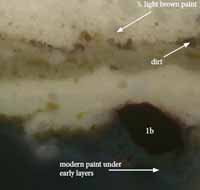

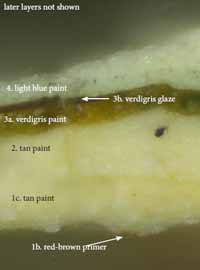

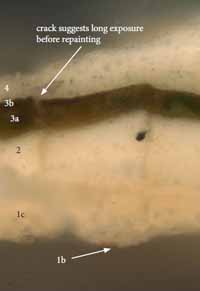

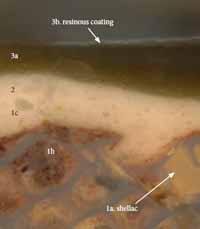

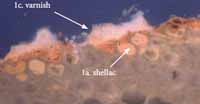

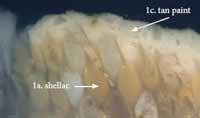

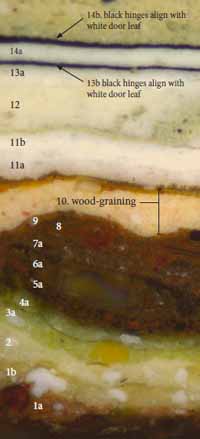

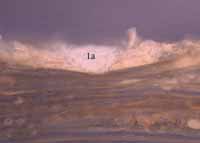

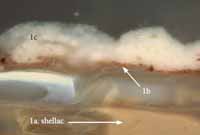

The results in this report are presented according to room, the first-floor west room being discussed first. Each section includes a floor plan of the house indicating the location of the space in question, a general description of the room, its history and its condition, sample location photographs, and an interpretation of the paint analysis results in prose accompanied by relevant cross-section photomicrographs. Where cross-section photomicrographs are shown, paint stratigraphies have been annotated according to finish "generation." For instance, a primer, paint layer, and varnish may represent one finish generation and are all given the same number, but differentiated with lowercase letters (1a, 1b, 1c, etc.), according to the order in which they would have been applied. Some paint samples contained redundant evidence, so only the most relevant samples are used in the report. Pigment identification with polarized light microscopy, binding media analysis with fluorochrome staining, and color matching are treated in separate sections at the end of the report. All results are interpreted in the conclusion, and all sampling memoranda and raw photomicrographs can be found in the appendix at the back of this report.

First floor, west room

Finnie House, first-floor plan. South central room in red.

Finnie House, first-floor plan. South central room in red.

General notes:

Kocher and Dearstyne describe this space as "one of the most elegantly proportioned house interiors in Williamsburg…the joinery is more elaborate than in other parts of the house and includes a modillion cornice, a heavy wall dado that projects at each window, forming a pedestal base to the window opening, and a boldly projecting baseboard." (Kocher and Dearstyne 1950, 20) .

The report notes that all of the woodwork in this room is original but was repaired and patched where necessary. These repairs were minimal. All of the plaster walls date to the restoration.

Results:

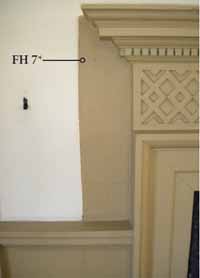

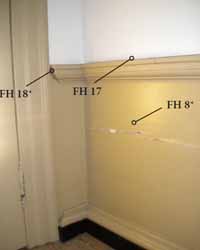

Twenty-one samples were taken from this room focusing on selected areas of woodwork including the mantel (FH 1-FH 7), the cornice (FH 9-FH 13), the wainscot (FH 8, FH 17, FH 18), the baseboard (FH 15, FH 16), the window architraves (FH 14), and both sides of the closet door leaf (FH 19-21).

The cross-section evidence suggests that all of the woodwork in this room was painted tan in the first generation with the exception of the baseboards, which were red-brown and varnished. The same tan paint was used on all woodwork throughout the house in this period.

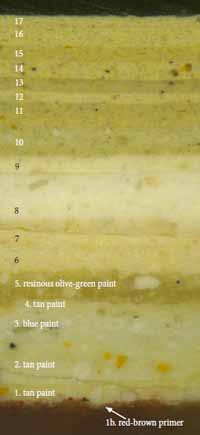

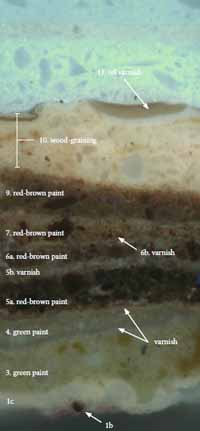

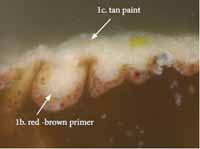

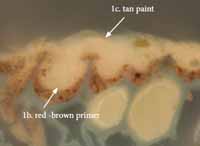

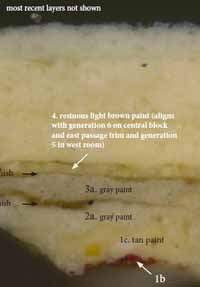

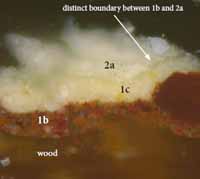

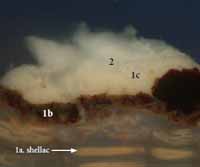

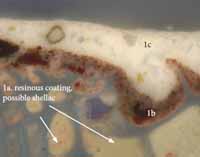

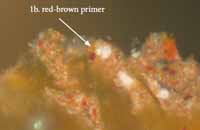

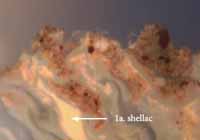

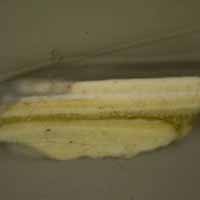

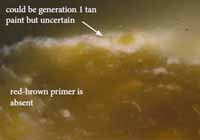

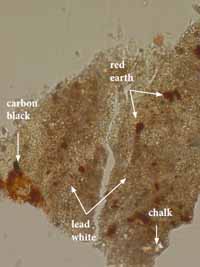

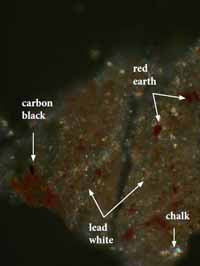

This first generation tan was built up with three layers: first, a pale orange autofluorescence in the wood substrate suggests that shellac was used to seal the surface before painting. This layer is designated 1a. Second, a thin, coarsely ground red-brown priming layer was applied to the wood. This layer is designated 1b. In cross-section, this red-brown primer contains large, coarsely ground deep red and white particles, as well as fine black particles visible at higher magnifications. Polarized light microscopy (PLM) of this layer suggests it contains red ochre, lead white, and carbon black pigments. Flurochrome staining suggests the red primer contains a minor carbohydrate component, possibly as a pigment dispersal agent, but stronger media reactions for oils or proteins were not seen. The finish layer is a tan-colored paint made with lead white and yellow ochre (see PLM results). This layer is designated 1c. Flurochrome staining was not able to determine the binding media, but its pinkish autofluorescence is suggestive of an oilbound lead whitebased paint.

8In the west room, none of the cornice samples contained the red-brown primer, although the shellac and first generation tan paint were present (p. 21-23). This could suggest that the cornice was a later addition that was painted to match the rest of the woodwork in the room, or that this element was made with a different type of wood that did not require a priming layer. Further analysis with techniques such as dendrochronology (for dating), or wood identification would be necessary to answer these questions.

Interestingly, the red-brown priming layer was also absent from the closet-side of the door leaf (FH 21, p. 25), while the room-side of the door leaf (FH 19, p. 24) contains the same paint history (including the red-brown primer), as the as other woodwork in this room. The reason for this discrepancy is unknown.

In the west room, the generations immediately following the first generation tan paint are a series of subtle light tan and light blue colors with very little dirt separating the generations, suggesting they were repainted frequently.

In the second generation, the tan paint appears to have been re-applied. In some samples, it is difficult to distinguish the first and second tan generations, but a distinct paint boundary between the two was observed in some samples, particularly FH 18 (surbase, p. 13), and FH 14 (window architrave, p. 15). This suggests that the first tan paint had dried completely before the second was applied. Since oil-bound paints are slow-drying, this boundary suggests the first generation had dried completely and a substantial amount of time had passed between the two generations.

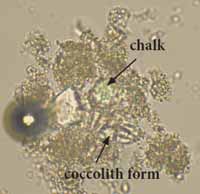

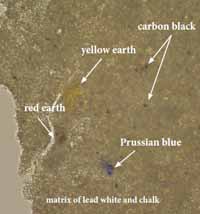

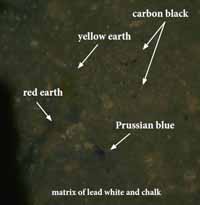

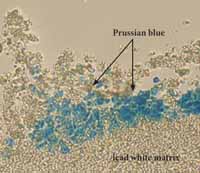

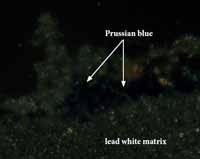

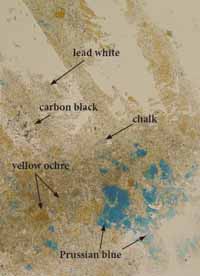

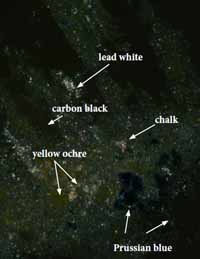

In the third generation, the woodwork was painted a pale blue color. Please note that, at high magnifications, this blue paint in cross-section looks very similar to the tan paints below it. However, examination of all uncast samples from the west room found each contained this light blue (see color matching section for a photomicrograph of an uncast sample containing the light blue, p. 108). Polarized light microscopy found that this light blue paint contains white lead, chalk, Prussian blue, and a small amount of red and yellow earth pigments. Binding media analysis with fluorochrome stains was inconclusive. Interestingly, the blue paint generation varies among the mantel samples. Some contain numerous layers of blue, white and possibly tan paints, but others contain only one blue paint and a layer of varnish. This discrepancy within a single generation suggests that the mantel was 'picked out' in varying shades of blue, or could have received a decorative finish in this period. Further on-site excavation of paint layers would be necessary to explore the nature of this finish.

In the fourth generation, the west room woodwork was painted tan again. In the fifth generation, an olive-green paint was used. This paint is highly autofluorescent in UV light, suggesting a resinous binding media. These resinous olive-green paints align with the sixth generation resinous light olive-colored paints that were found on the woodwork in the central block and east passage of the house in the same generation.

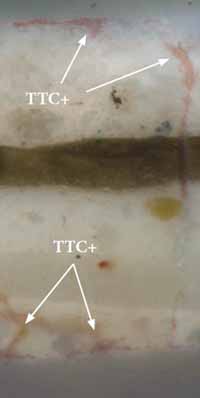

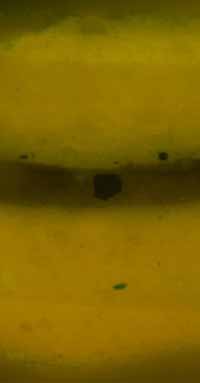

Possible wallpaper evidence was found in sample FH 7, taken from the vertical facing of the mantel that is flush with the wall. This sample contained only the first tan paint generation, a tannish material not seen elsewhere, and the fifth generation resinous olive-green paint. Generations 2-4 were missing. Fluorochrome staining with TTC determined that the tannish material is a carbohydrate, most likely a starch-based wallpaper paste (p. 93). This would indicate that the walls were wallpapered early in the history of the room, possibly from generations 2-4.

9| Generation | Layer | Description | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 5b | resinous olive-green paint on trim, second layer | aligns with generation 6 resinous light-olive paints in central block and east passage |

| 5a | resinous olive-green paint on trim (baseboards red-brown) | aligns with generation 6 resinous light-olive paints in central block and east passage | |

| 4 | 4b | varnish with dim autofluorescence (possibly oil bound) | very thin, not seen in all samples |

| 4a | tan paint, similar to generations 1 and 2 (baseboards red-brown, walls may have been wallpapered) | ||

| 3 | 3a | pale blue paint made with lead white, chalk, Prussian blue and earth pigments (baseboards red-brown, walls may have been wallpapered) | seen on all woodwork in this room, closet doors may have been a paler shade, and mantel may have received a decorative finish that was varnished. |

| 2 | 2 | tan-colored paint (baseboards red-brown, walls may have been wallpapered) | seen on all woodwork in this room, but no red-brown primer on cornice or inferior side of closet door. Same tan paint used throughout house in first and second generation |

| 1 | 1c | tan-colored paint made with lead white and yellow ochre (baseboards varnished) | seen on all woodwork in this room, but no red-brown primer on cornice or inferior side of closet door. Same tan paint used throughout house in first and second generation |

| 1b | thin red-brown primer (baseboards red-brown) | seen on all woodwork in this room, but no red-brown primer on cornice or inferior side of closet door. Same tan paint used throughout house in first and second generation | |

| 1a | shellac sealant on wood substrate | seen on all woodwork in this room, but no red-brown primer on cornice or inferior side of closet door. Same tan paint used throughout house in first and second generation |

First-floor, west room, sample locations (* indicates sample discussed in report)

West wall, mantel (south face)

West wall, mantel (south face)

Southwest corner, adjacent to closet

Southwest corner, adjacent to closet

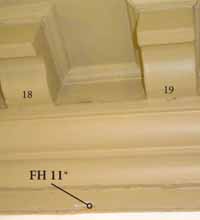

All cornice samples taken from the south wall. The modillions are numbered from the east.

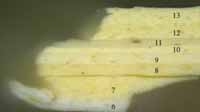

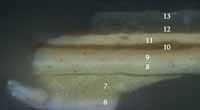

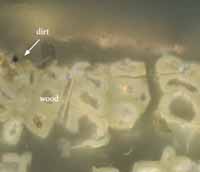

12First floor, west room: surbase

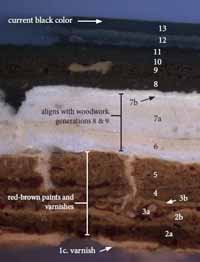

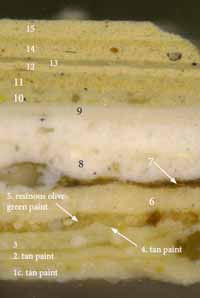

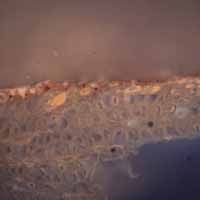

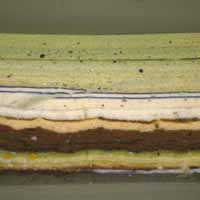

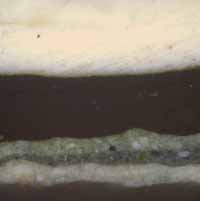

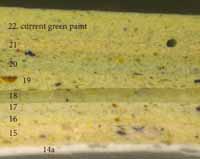

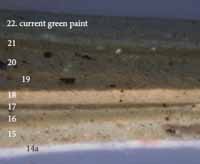

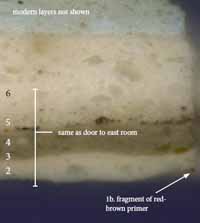

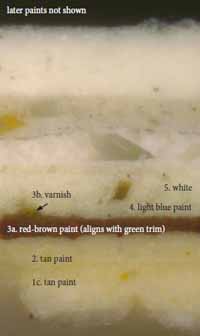

Sample FH 18: east wall surbase, ovolo of bed mold

Seventeen paint generations were identified on the east wall surbase, beginning with the first generation red-brown primer and tan paint. Generation three is a light blue not seen anywhere else in the house during this period. (Please note that, at high magnifications, the light blue paint in cross-section looks very similar to the tan paints below it. However, examination of all uncast samples from the west room found this light blue (for a photomicrograph of an uncast sample containing the light blue, see p. 109). This sample is comparable to the paints found on the flush board dado (sample FH 8, p. 14), and the window architrave (FH 14, p. 15), suggesting that all of the west room trim received the same decorative finish in the early history of the house.

First floor, west room: wainscot

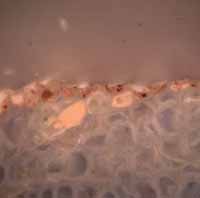

Sample FH 8: south wall wainscot, flush board dado

This sample is comparable to the paints found on the window architrave (sample FH 14, p. 15), and the surbase (FH 18, p. 13), suggesting that all of the west room trim received the same decorative finish in the early history of the house. Only the earliest paint generations are pictured here, but up to 17 generations of paint were found on the trim.

First floor, west room: window architrave

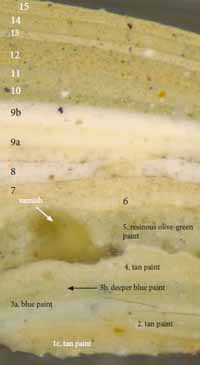

Sample FH 14: southeast window architrave, west jamb, top of bottom cyma

This sample is comparable to the paints found on the flush board dado (sample FH 8, p. 14), and the surbase (FH 18, p. 13), suggesting that all of the west room trim received the same decorative finish in the early history of the house. Only the earliest paint generations are pictured here, but up to 17 generations of paint were found on the trim.

First floor, west room: baseboard

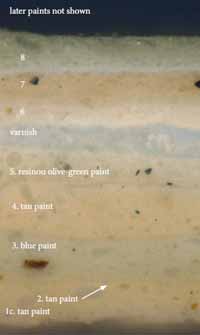

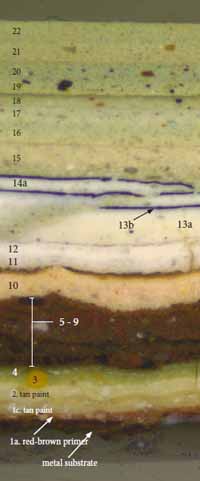

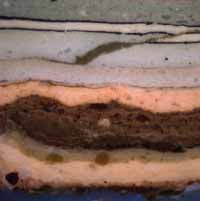

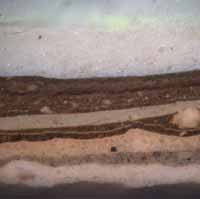

Sample FH 16: east wall, baseboard

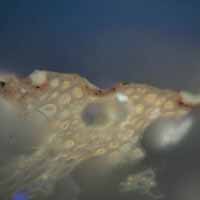

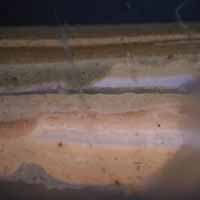

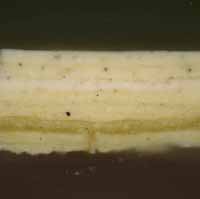

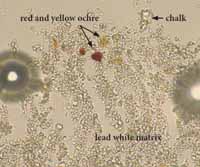

FH 16, visible light, 200x. Early layers on substrate.

FH 16, visible light, 200x. Early layers on substrate.

FH 16, UV light, 200x. Early layers on substrate.

FH 16, UV light, 200x. Early layers on substrate.

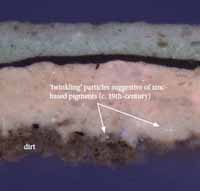

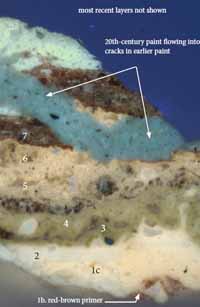

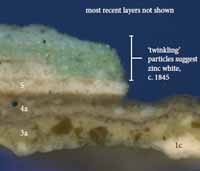

Thirteen paint generations were found on the baseboards. The paint evidence suggests that they were almost always painted differently from the rest of the woodwork in this room (possible exceptions being generations 6 and 7). In the first generation, the baseboards were sealed with shellac (1a) and painted dark red-brown (1b). In comparison with the first generation red primer seen throughout the house, the first generation paint on the baseboards has a similar thickness and pigment dispersion, and it could have been applied at the same time as the red-brown primer, but it is clearly not the same coating. It appears to have been simply varnished (1c). The bright white autofluorescence of this varnish suggests a plant resin source. The baseboards continued to be painted dark red or red-brown and varnished until generation 6 and 7, when it was painted white with what appears to be a zinc-based pigment (indicated by the 'twinkling' autofluorescent particles, and introduced after c. 1845). Generations 6 and 7 on the baseboards appear to align with white paint generations 8 and 9 on the rest of the woodwork in the room.

First floor, west room: Mantel

Sample FH 2: mantel, south end, bottom fillet of bed mold between first two dentils

Fifteen paint generations were found on the mantel. The paint evidence suggests that in the first two generations, the mantel was painted tan to match the rest of the woodwork in this room. In the third generation, the mantel appears to have been painted with a light blue base coat that matched the rest of the woodwork, but this sample from the bed mold (FH 2) and sample FH 5 from the raised fretwork revealed some additional blue paint layers between generations 3 and 4, another tan paint. These paints are very lightly pigmented and do not align between samples (one deeper blue layer is present in FH 2, while more tans and a white paint are present in FH 5), suggesting that some subtle color variation may have been extant on the mantel in the third generation, or that some mantel elements were picked out in shades of blue in this generation. However the exact nature of this decorative finish, if it is present, cannot be determined through cross-section microscopy alone. More extensive on-site paint excavations would need to be carried out to explore this finish further.

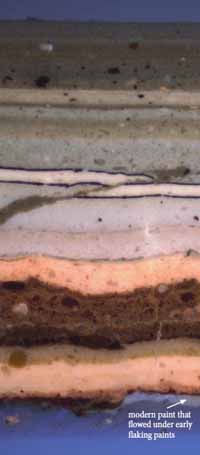

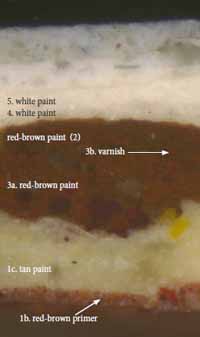

Sample FH 3: mantel, south end, bottom of cyma recta, 1" out from wall plaster

Fifteen paint generations are extant on the mantel, but only the early paints are shown here. The mantel retains the first and second generation tan paints, but the third blue paint generation varies between mantel samples FH 2 (previous page), and FH 5 (next page). In sample FH 3 (shown here), the third generation blue is very lightly pigmented and coated with only a thin varnish layer, the dim autofluorescence of which suggests an oil binder. By comparison, in sample FH 5 (next page), multiple paint layers were seen here while in sample FH 2 (previous page), no oil varnish was observed, but one layer of a deeper blue paint was present. The comparative evidence suggests that in generation 3, the mantel may have received some type of multi-layered decorative finish.

Sample FH 5: mantel, front face, surface of raised fretwork

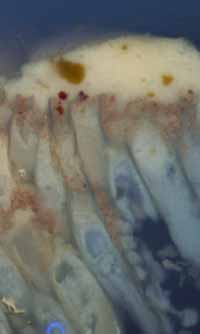

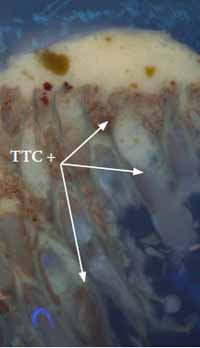

Sample FH 7: mantel, vertical face, flush with wall plaster

Sample FH 7 is missing paint generations 2-4, and instead a tannish layer with a bluish autofluorescence is present. Since this surface is flush with the wall, it is suspected that this material was a wallpaper paste residue, and fluorochrome staining with TTC tagged carbohydrates in this layer (see fluorochrome staining section, p. 93). This would suggest that the walls, as well as the vertical face of the mantel, may have been wallpapered in generations 2-4. It is possible that the walls were wallpapered in other generations as well, but the vertical mantel panel was most likely not wallpapered, as its paint history aligns with the rest of the woodwork.

First floor, west room: Cornice

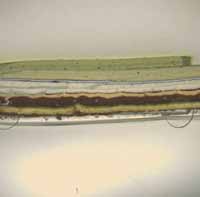

Sample FH 10: south wall, cornice, top of bottom fascia below bed mold

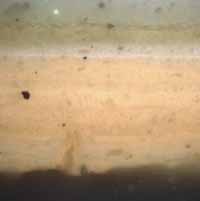

FH 10, visible light, 200x. Wood substrate and early paint.

FH 10, visible light, 200x. Wood substrate and early paint.

FH 10, UV light, 200x. Wood substrate and early paint.

FH 10, UV light, 200x. Wood substrate and early paint.

Fifteen paint generations were identified on the cornice (see sample FH 11). There was no red-brown primer in any of the cornice samples, although the shellac sealant (1a) and first generation tan paint (1c) were observed. With the exception of the missing red primer, these early cornice paints align with the finishes applied to the rest of the woodwork in this room.

Sample FH 12: south wall, cornice, top of rear fascia at intersection with 21st modillion

FH 12 (2), visible light, 200x

FH 12 (2), visible light, 200x

Again, the first generation red-brown priming layer (1b) was not applied to the cornice. However, the first generation shellac sealant (1a), and tan paint (1c) are present.

Sample FH 11: south wall, cornice, bottom of fascia adjoining wall plaster

The early paint stratigraphy in sample FH 11 is rather disrupted, but the tannish, translucent material at the bottom of the sample was not seen elsewhere. Since this area of the cornice is flush with the wall plaster, it was suspected that this material could be a starch-based wallpaper paste that overlapped onto the cornice. The sample was stained with TTC to tag for the presence of carbohydrates in the tannish material. A positive reaction could suggest that a starch-based paste residue was present, further suggesting that the walls were wallpapered. However, no reaction was observed, and the material remains unidentified (see Fluorochrome staining section, p. 94).

First floor, west room: closet door leaf (room-side)

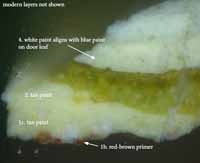

Sample FH 19: Closet door leaf, (room-side), top of middle rail, 4" south of middle stile

In general, the early paint history of the room-side of the closet door leaf aligns with the woodwork finishes in the rest of the room. The red-brown primer and first and second generation tan paints are seen. In the third generation, the door leaf appears to have been painted with a light blue, as was the rest of the woodwork in this period. However, comparison of uncast sample portions from the closet door and the mantel suggest that the blue on the closet door is somewhat paler and more yellow (although this could result from inherent color variations in hand ground paints and/or oxidation of the oil binding medium).

First floor, west room: closet door leaf (Closet-side)

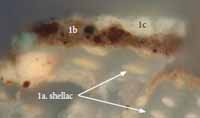

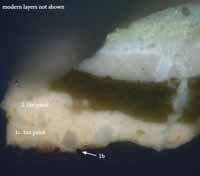

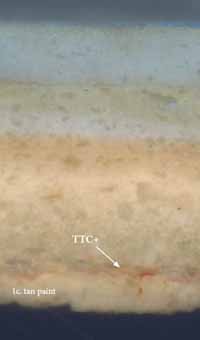

Sample FH 21: Closet door leaf, (closet-side), upper south corner of lower south panel

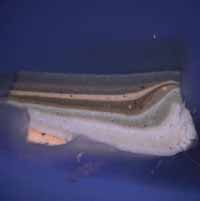

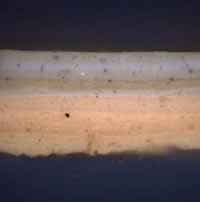

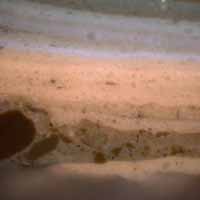

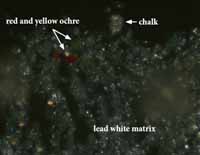

FH 21, visible light, 400x. Early layers on substrate.

FH 21, visible light, 400x. Early layers on substrate.

FH 21, UV light, 400x. Early layers on substrate.

FH 21, UV light, 400x. Early layers on substrate.

The red-brown primer (1b) was not found on the inferior-side of the closet door leaf, although the wood substrate does appear to have been sealed with shellac (1a), and painted tan (1c), like the other side of the door (FH 19). Like sample FH 19, after the first tan generation, the earliest paints have such subtle colors that they are difficult to differentiate at high magnification. Examination of an uncast portion of this particular sample was not able to find the light blue paint used on the rest of the woodwork in this room, although the same number of layers are present in the cross-section. It is possible that the door was painted a neutral color at that time, and the more expensive blue pigment was used on visible surfaces, like the other side of the door.

First floor, Front Passage

Finnie House, first-floor plan. Front passage in red.

Finnie House, first-floor plan. Front passage in red.

General notes:

The central block was originally intended as one large room. In the 1950 report, Kocher and Dearstyne write that before the restoration, a vestibule of later origin "intervened between the main entrance doorway and the large center room," which was removed during the restoration (Kocher and Dearstyne 1950, 3). However, other partitions have been constructed since that time to separate the central block into the present three units- the kitchen, the 'south central' room, and the front passage. Much of the woodwork along the perimeter of the central block is original, including the chair rails and baseboards, the cornice, the door and window architraves, and the front (north) door leaf, trim, and HL hinges. The east door leading to the east passage is original, but the west door leading to the vestibule before the west room was relocated, possibly from the west room to become the west vestibule entrance door. The report does not mention where the present west passage door originates from. On-site observation suggests that the south wall of the current front passage appears to have been outfitted with original wainscot flush panelling from the adjacent south central room. (Chappell 2011, Appendix C). The plaster walls date to the restoration.

Results:

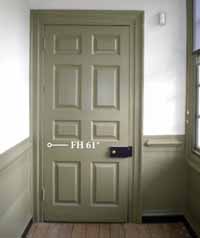

Seven samples were taken from this space focusing on the chair rails (FH 22 and FH 23), the north (front) door leaf, hinge, and architrave (FH 24 — FH 26), and the door leaves to the east passage (FH 60), and the door leaf to the vestibule before the west room (FH 61). The sample removed from the window architrave on the south wall of the adjacent south central room (FH 27), should also be considered with this group, considering that the central block was originally laid out as one large space (see South Central Room section).

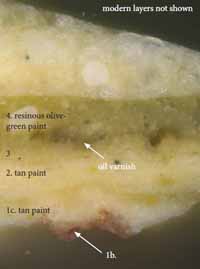

The cross-section evidence suggests that the first finish on all of the woodwork in this room was the tan color used in the west room as well as throughout the house in this first period. This first generation was built up with three layers consisting of the shellac sealant (1a), a thin red-brown primer (1b), and a tan-colored paint (1c), made with lead white and yellow ochre.

Generation 2 is another tan-colored paint. This generation was found on all of the woodwork sampled in this room. Like generation 1, this paint also contains coarsely ground yellow particles that appear to be yellow ochre, although this paint could not be isolated for pigment identification. There is no dirt separating generations 1 and 2, which indicates that the room was repainted within a short period of time, but the distinct boundary between the first two paint generations does suggest these finishes are independent of one another. This boundary is seen in samples FH 25 (p. 34), and FH 26 (p. 30).

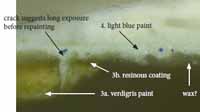

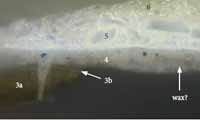

27In the third generation, the woodwork in the front passage was painted an olive-green color. This paint was most certainly hand ground, as it contains large yellow, black, and blue pigment particles in a green matrix. It was coated with a very thin layer of varnish, the dim autofluorescence of which suggests a high oil component. This same color and varnish was reapplied in the fourth generation, although the paint is not as coarsely ground.

In generations 5 and 6, the chair rail and window and door architraves were painted a light brown and olive green colors, respectively, while the door leaves were painted red-brown. The brown paint has a translucency that was observed in the uncast portion, and in reflected UV light these paints are very autofluorescent (particularly generation 6), suggesting a high resin component that would have lent a glossy surface to the finish. The red-brown on the door leaves is coarsely ground and coated with a varnish that appears rather worn and degraded.

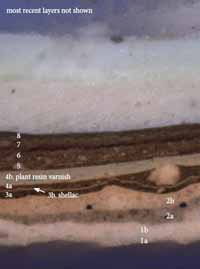

It is worth noting that comparison of the samples from the front door leaf (FH 24, p. 31-32) and HL hinge (FH 25, p. 33-34) indicate that from generations 1-12 the hardware received the same painted finish as the door. These finishes ranged from tan, green, and red-brown paints (generations 5-9) and included a faux-wood graining finish in the 10th generation. However, in generations 13 and 14, the hinges were painted black while the door leaf was white. This was a popular "colonial revival" color scheme in the 20th century, yet the early history of these samples provide clear evidence that this scheme was a modern invention.

| Generation | Layer | Description | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 6b | varnish with dim autofluorescence (possibly oil bound) | also seen in south central room, and in first-floor west room |

| 6a | resinous light olive-green paint on trim, red-brown paint with varnish on front door leaf and hinge | also seen in south central room, and in first-floor west room | |

| 5 | 5b | varnish with dim autofluorescence, (possibly oil bound) | also seen in south central room |

| 5a | resinous light brown paint on trim, red-brown paint with varnish on front door leaf and hinge | also seen in south central room | |

| 4 | 4b | varnish with dim autofluorescence (possibly oil bound) | very thin, not seen in all samples |

| 4a | olive-green paint, very similar to 3a but does not contain the same large coarsely ground particles | seen on all woodwork in this room, also seen in south central room | |

| 3 | 3b | varnish with dim autofluorescence (possibly oil bound) | very thin layer |

| 3a | coarsely ground olive-green paint containing large yellow, white, red, and blue pigment particles in a light green matrix. | seen on all woodwork in this room, also seen in south central room | |

| 2 | 2 | tan-colored paint | seen on all woodwork in this room, same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

| 1 | 1c | oil-bound tan-colored paint made with lead white and yellow ochre | seen on all woodwork in this room, same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

| 1b | thin red-brown primer | seen on all woodwork in this room, same chronology seen throughout house in first generation | |

| 1a | shellac sealant on wood substrate | seen on all woodwork in this room, same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

First floor, front passage, sample locations (* indicates sample discussed in report)

First-floor, front passage, east wall (door to east passage)

First-floor, front passage, east wall (door to east passage)

First-floor, front passage, west wall (door to vestibule before west room)

First-floor, front passage, west wall (door to vestibule before west room)

First floor, front passage

Sample FH 22: east wall, surbase of bolection molding, torus, top adjoining cyma

FH 22 (wood substrate), visible light, 200x

FH 22 (wood substrate), visible light, 200x

FH 22 (wood substrate), UV light, 200x

FH 22 (wood substrate), UV light, 200x

The same early paint history is also seen on the architrave of the north (front) door in the front passage (FH 26, p. 30), and the window architrave in the present south central room (FH 27, p. 40). This is consistent with the knowledge that the central block was originally constructed as one large space in the 18th century.

Sample FH 26: Front door architrave, west backband cyma at outer fillet

FH 26 (wood substrate), visible light, 200x

FH 26 (wood substrate), visible light, 200x

FH 26 (wood substrate), UV light, 200x

FH 26 (wood substrate), UV light, 200x

The same early paint history is also seen on the chair rail surbase on the east wall (FH 22, p. 29), and the window architrave in the present south central room (FH 27, p. 40). This is consistent with the knowledge that the central block was originally constructed as one large space in the 18th century.

Sample FH 24: Front door leaf, interior face, upper molding on lower west panel

FH 24 (recent paints), visible light, 200x

FH 24 (recent paints), visible light, 200x

FH 24 (recent paints), UV light, 200x

FH 24 (recent paints), UV light, 200x

FH 24 (early paints), visible light, 200x

FH 24 (early paints), visible light, 200x

FH 24 (early paints), UV light, 200x

FH 24 (early paints), UV light, 200x

Sample FH 24: Front door leaf, interior face, upper molding on lower west panel (detail)

FH 24 (early paints), visible light, 400x

FH 24 (early paints), visible light, 400x

FH 24 (early paints), UV light, 400x

FH 24 (early paints), UV light, 400x

The earliest paints in sample FH 24 are shown here in greater detail to clarify the finish layers. Generations 1-4 are the same as those seen on the trim in this space. However, in generations 5 and 6, the door leaf was painted red-brown, while the trim was painted with a resinous tan paint (compare to FH 26, p. 30).

Sample FH 25: Front door leaf, lower HL hinge.

Twenty-two paint generations were found on the front door. Further discussion on next page.

Sample FH 25: Front door leaf, lower HL hinge (detail)

FH 25 (early paints), visible light, 100x

FH 25 (early paints), visible light, 100x

FH 25 (early paints), UV light, 100x

FH 25 (early paints), UV light, 100x

The earliest paints in sample FH 25 are shown here in greater detail. Comparison with this sample and the sample taken from the door leaf (FH 24, p. 31-32), indicates that from generations 1-12 the hardware received the same painted finish as the rest of the door. These finishes ranged from green to red-brown paints and included faux-wood graining. In generations 13 and 14, the hinges were painted black while the door leaf was white. This was considered a "colonial revival" color scheme, yet these samples provide clear evidence that illustrate how this popular "colonial" scheme was a modern invention.

Sample FH 60: door leaf to the east passage, passage-side, center stile, 2' up from floor.

The same paint history is also seen on the passage side of the front (north) entrance door leaf and hinge (FH 24, p. 31-32, and FH 25, p. 33-34), suggesting that all of the doors in the front passage were finished in a similar manner.

Sample FH 61: door leaf to the west room, passage-side

This particular door is not mentioned in the architectural report, but comparison of this sample to the other front passage door leaves discussed in this section (FH 24, p. 31-32, and FH 60, p. 35), suggests that this door is not original to the front passage. However, its early paint history is more similar to the west room woodwork, suggesting that this door originates from that space. The report does relate that the current west room entrance door (not sampled) was moved from the front passage (Kocher and Dearstyne 1950, 36), so it seems that the doors were switched at some point.

First floor, South central room

Finnie House, first-floor plan. South central room in red.

Finnie House, first-floor plan. South central room in red.

General notes:

As mentioned previously, the first floor of the central block was originally one large space. At some point after the initial restoration, the present south central room was created when the north and east walls were added to create the kitchen and front passage spaces. The trim on the south and west walls is original, but the south door architrave and leaf date to the restoration. The mantel on the west wall was moved into this room from the now-lost south (rear) wing of the house. It was hoped that the paint history of the mantel would help elucidate whether the lost wing was original to the house, or an early addition. The plaster walls were not sampled because the restoration report states that they were replaced in the 20th century.

Results:

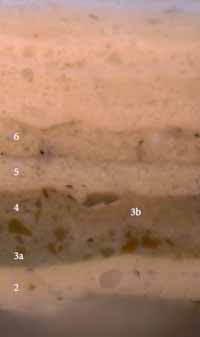

Three samples were taken focusing on the architrave of the southwest window (FH 27), and the mantel (FH 28, FH 29).The early paint history of the window architrave on the south wall is the same as that seen on the trim in the present front passage east wall (compare to samples FH 22 and FH 26), starting with the shellac sealant on wood (1a), red-brown primer (1b), and oil bound tan paint (1c), that was seen throughout the house. This is followed by another tan paint (2), two generations of olive-green paints (3 and 4), and two resinous light brown and olive-green paint generations (5 and 6). This is consistent with the understanding that the central block was originally one large space in the 18th century.

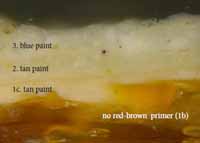

Both mantel samples appeared to contain the same paint evidence, and only FH 28 was cast and discussed here. The paint history of the mantel was found to be very different from that of other woodwork in the house. The first generation red-brown primer and tan paint found throughout the house is absent from the mantel. Instead, the first two generations are gray paints, followed by six generations of black paints with varnish coatings. None of these paints could be aligned with other elements in the house to determine when the mantel was installed. These did not appear to be the same early grays used in the east room (see East Room section). The absence of the first-period red-brown primer and tan paint strongly suggests that this mantel, and the south (rear) wing from which it originates, date to a later period of construction.

38| Generation | Layer | Description | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 6 | resinous light olive paint | also seen on front passage trim and in first-floor west room |

| 5 | 5 | resinous light brown paint | also seen on front passage trim and in first-floor west room |

| 4 | 4b | varnish with dim autofluorescence (possibly oil bound) | also seen on front passage trim, but not seen in all samples |

| 4a | olive-green paint, very similar to 3a but does not contain the same large coarsely ground particles | also seen on front passage trim | |

| 3 | 3b | varnish with dim autofluorescence (possibly oil bound) | also seen on front passage trim, but not seen in all samples |

| 3a | coarsely ground olive-green paint containing large yellow, white, red, and green pigment particles in a light green matrix. | also seen on front passage trim | |

| 2 | 2 | tan-colored paint | same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

| 1 | 1c | oil-bound tan-colored paint made with lead white and yellow ochre | same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

| 1b | thin red-brown primer | same chronology seen throughout house in first generation | |

| 1a | shellac sealant on wood substrate | same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

First floor, South Central Room, sample locations (* indicates discussed in report)

First-floor, south (rear) central room, south wall window architrave

First-floor, south (rear) central room, south wall window architrave

First-floor, south (rear) central room, west wall

First-floor, south (rear) central room, west wall

Sample FH 27: Window architrave, east side, inner cyma

Sample FH 27: Window architrave, east side, inner cyma (detail)

FH 27 (early layers), visible light, 400x

FH 27 (early layers), visible light, 400x

FH 27 (early layers), UV light, 400x

FH 27 (early layers), UV light, 400x

The earliest paint layers from sample FH 27 (previous page) are shown here in greater detail. The same early paint history is also seen in the front passage on the east chair rail surbase (FH 22, p. 29), and the front (north) door architrave (FH 26, p. 30). This is consistent with the knowledge that the central block was originally one large space in the 18th century.

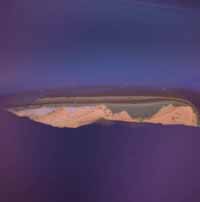

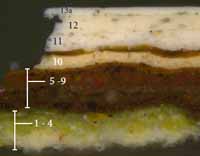

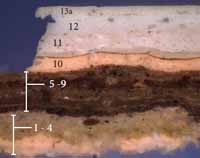

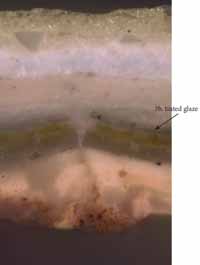

Sample FH 28: mantel, south end (return) of ovolo in crown molding above dentils

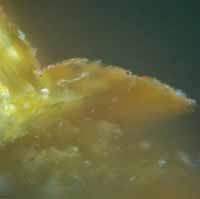

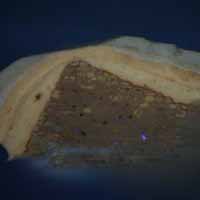

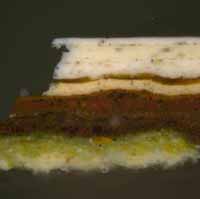

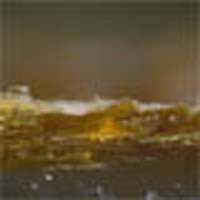

FH 28 (early layers), visible light, 200x

FH 28 (early layers), visible light, 200x

FH 28 (early layers), UV light, 200x

FH 28 (early layers), UV light, 200x

FH 28 (wood substrate), visible light, 200x

FH 28 (wood substrate), visible light, 200x

FH 28 (wood substrate), UV light, 200x

FH 28 (wood substrate), UV light, 200x

This mantel was moved into the south central room from the now-lost south addition to the house. The absence of the first-period red-brown primer and tan-colored paint strongly suggests that the mantel, and therefore the south addition from which the mantel originates, dates to a later period.

First floor, East room

Finnie House, first-floor plan. East room in red.

Finnie House, first-floor plan. East room in red.

General notes:

Kocher and Dearstyne (1950) refer to this space as a dining room. The baseboard, chair rail, cornice are original, as are the window frames and trim on the north and south elevations. The door leaf and architrave to the passage are also original. The report seems to suggest that the mantel was brought in, but is somewhat ambiguous (Kocher and Dearstyne, p. 40 reads "mantel is not original to this house," yet p. 41 reads "the mantel in the dining room is old with some evidence of patching.")

Results:

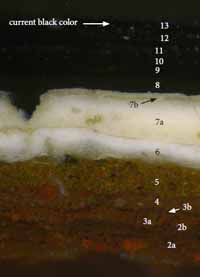

Six samples were taken from this space focusing on the mantel (FH 38 — FH 40), the chair board (FH 41), the north window architrave (FH 42), and the room-side of the door leaf (FH 43).

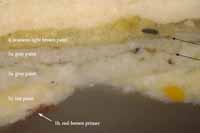

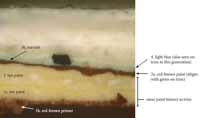

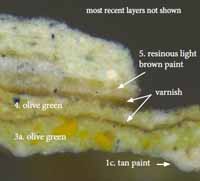

The paint evidence on the chair rail, window architrave, and door leaf suggests that the trim in this room received the same decorative treatment as the rest of the house in the first generation, consisting of the shellac sealant (1a), a thin red-brown primer (1b), and a tan-colored paint (1c). However, in the second generation, while the rest of the woodwork in the house was repainted tan, the trim in this room was painted gray.

In the third generation, the trim was painted gray again, this time in a slightly darker tone than the previous generation. Both of these gray paints were coated with a thin layer of varnish. These varnishes have a dim autofluorescence suggesting a high oil component. Generation 4 is a light brown color whose autofluorescence suggests a high resin component. This tan paint appears to be the same as paint generation 6 on the trim in the central block and east passage, which also aligns with generation 5 in the first-floor west room.

The three samples collected from the mantel seem to contain different paints from the trim in this room. Sample FH 40 contained modern paints only and was not cast. Samples FH 38 and FH 39 contained similar paint evidence and FH 38 is used here for discussion. The early paints are very disrupted and difficult to interpret, but the first-period red-brown primer and second-period gray paints found on the trim were not seen here. This could suggest that the mantel is not original, but more confident conclusions could not be made at this time.

44| Generation | Layer | Description | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 4 | resinous light brown-colored paint | aligns with generation 6 on central block and east passage trim, and generation 5 in west room |

| 3 | 3b | varnish with dim autofluorescence (possibly oil bound) | seen only in this space |

| 3a | gray paint | seen only in this space | |

| 2 | 2b | varnish with dim autofluorescence (possibly oil bound) | seen only in this space |

| 2a | gray paint | seen only in this space | |

| 1 | 1c | oil-bound tan-colored paint made with lead white and yellow ochre | same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

| 1b | thin red-brown primer | same chronology seen throughout house in first generation | |

| 1a | shellac sealant on wood substrate | same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

First floor, east room sample locations (*indicates discussed in report)

West wall, entrance door (room-side)

West wall, entrance door (room-side)

Sample FH 42: north window architrave, outer fillet of west backband

Sample FH 41: East wall, chair board, bottom face at lower bead

Sample FH 43: Room-side of door leaf, molding on raised field of lower south panel

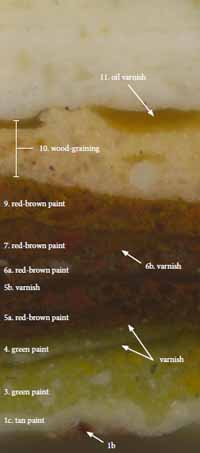

Sample FH 38: mantel frieze, south edge, 1" above architrave

FH 38, visible light, 100x, top layers

FH 38, visible light, 100x, top layers

FH 38, UV light, 100x, top layers

FH 38, UV light, 100x, top layers

FH 38, visible light, 400x., wood substrate and early layers

FH 38, visible light, 400x., wood substrate and early layers

FH 38, UV light, 400, wood substrate and early layers

FH 38, UV light, 400, wood substrate and early layers

The paint history of the mantel could not be directly linked to other woodwork in the east room or in the rest of the house. The first generation red primer is absent, and the earliest layer could be the tan paint, but it is present only in fragments on the wood substrate, making it difficult to interpret. Similarly, disrupted remnants of the 4th generation resinous light brown paint may be present on the bottom of this sample (see top images), but its deterioration complicates the interpretation.

First floor, East Passage

Finnie House, first-floor plan. East passage in red.

Finnie House, first-floor plan. East passage in red.

General notes:

The woodwork in this space is original, with the exception of the partition between the east passage and the vestibule before the east room, which is a modern addition.

Results:

Four samples were taken from this space focusing on the door leaf to the front passage (FH 30), the door architrave and leaf to the east room (FH 31, FH 62), and the rear (south) entry door FH 32). Interestingly, the results suggest that the east passage received the same decorative treatments as the central block, suggesting a chromatic connection between the two spaces.

The early paint history of all samples from this space are comparable, starting with the first generation shellac sealant (1a), red-brown primer (1b), and oilbound tan paint (1c), that was found throughout the house in this period.

This is followed by the second generation tan paint , also seen throughout the house with the exception of the east room. The third and fourth finish generations are olive-green paints coated with thin varnishes. This color was found on the trim and the door leaves, but the varnish was not present in all samples. In the fifth generation, the woodwork was painted with a somewhat translucent light brown paint. This paint is very autofluorescent in UV light, suggesting a high resin component. This same resinous brown paint was also found in the central block woodwork. In the passage, this brown resinous paint was used on the architrave and door leaves, but in the central block it was only used on the trim while the leaves were painted red-brown.

51| Generation | Layer | Description | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 6a | white on trim, light brown on south door leaf | light brown also seen in central block trim |

| 5 | 5b | varnish with dim autofluorescence, (possibly oil bound) | also seen in central block trim, but with red-brown door leaves |

| 5a | resinous light brown paint on trim and door leaves | also seen in central block trim, but with red-brown door leaves | |

| 4 | 4b | varnish with dim autofluorescence (possibly oil bound) | seen on all woodwork in this room, also seen on central block woodwork, varnish is very thin, not seen in all samples |

| 4a | olive-green paint, very similar to 3a but does not contain the same large coarsely ground particles | seen on all woodwork in this room, also seen on central block woodwork, varnish is very thin, not seen in all samples | |

| 3 | 3b | varnish with dim autofluorescence (possibly oil bound) | seen on all woodwork in this room, also seen on central block woodwork |

| 3a | coarsely ground olive-green paint containing large yellow, white, red, and green pigment particles in a light green matrix. | seen on all woodwork in this room, also seen on central block woodwork | |

| 2 | 2 | tan-colored paint | seen on all woodwork in this room, same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

| 1 | 1c | oil-bound tan-colored paint made with lead white and yellow ochre | seen on all woodwork in this room, same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

| 1b | thin red-brown primer | seen on all woodwork in this room, same chronology seen throughout house in first generation | |

| 1a | shellac sealant on wood substrate | seen on all woodwork in this room, same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

First floor, east passage sample locations

East side of east passage door leading to front passage

East side of east passage door leading to front passage

West side of east passage door leading to east room

West side of east passage door leading to east room

Interior side of south (rear) door

Interior side of south (rear) door

Sample FH 31: north architrave of door to east room

FH 31 (early layers only), visible light, 400x

FH 31 (early layers only), visible light, 400x

FH 31 (early layers only), UV light, 400x

FH 31 (early layers only), UV light, 400x

FH 31 (early layers only), visible light, 400x

FH 31 (early layers only), visible light, 400x

FH 31 (early layers only), UV light, 400x

FH 31 (early layers only), UV light, 400x

Generations 1-5 are comparable to those found on the trim in the central block, suggesting that in the early history of the house, both spaces were finished in the same manner.

Comparison of this sample with sample FH 62 indicates that in the east passage, the door leaves and architraves received the same finish in generations 1-5 (see next page).

Sample FH 62: door leaf to east room (early layers only)

The early paint history seen here from the door leaf aligns with that found on the door architrave (FH 31). This finish history is also very similar to what was seen in the central block with the exception of generation 5. In the fifth generation in the central block, the same resinous light brown paint was found on the trim, but the door leaves were painted red-brown (see samples FH 24 - FH 26, discussed in the front passage section, p. 30-34). By contrast, these samples clearly show that in the fifth generation the east passage trim and door leaves were painted light brown.

Sample FH 30: east side of door leaf to front passage, lower right stile, cyma molding at intersection with lock rail.

FH 30 (early layers only), visible light, 200x

FH 30 (early layers only), visible light, 200x

FH 30 (early layers only), UV light, 200x

FH 30 (early layers only), UV light, 200x

Sample FH 32: south (rear) door, interior face, west (hinged) stile

FH 32 (early layers only), visible light, 200x

FH 32 (early layers only), visible light, 200x

FH 32 (early layers only), UV light, 200x

FH 32 (early layers only), UV light, 200x

The early paint evidence contained in sample FH 32 indicates that in generation 1-5, the rear (south) door leading outside from the east passage was finished in the same manner as the rest of the east passage woodwork. However, in generation 6, the resinous light brown paint similar to generation 5 was re-applied. This re-application was not found on any of the other elements in the east passage.

In comparison to the front (north) door (FH 25-FH 26, p. 30, 33-34), the first four finish generations seen on the rear door are the same, but in generations 5-6 the rear door was painted light brown like the east passage woodwork, while the front door was painted red-brown.

Staircase

Finnie House, first-floor plan. Staircase in red.

Finnie House, first-floor plan. Staircase in red.

General notes:

The report states that "the stairway to the second floor main house appears to be original throughout" although a few of the balusters are new, as is the newel post at the second floor, and the half newel against the second-floor wall (Kocher and Dearstyne 1950, 52). The stringers, handrail, risers and treads are also original, but repaired and patched with antique material where necessary. The handrail was not sampled as on-site excavations found only a modern clear coating.

Results:

Five samples were collected from the staircase. These comprised the stair riser (FH 33), the newel post (FH 34), the upper stringer (FH 35), the half baluster attached to the newel (FH 36), and the lower stringer (FH 37).

The evidence suggests that the newel post, upper stringer, and balusters were all painted tan in the first period. As seen throughout the house, this finish is comprised of a shellac sealant (1a), a red-brown primer (1b), and an oilbound tan paint (1c) made with white lead and yellow ochre. The second generation tan paint was found on the half baluster, but not on the newel post or upper stringer. It is possible that this layer is missing from these samples, or that these elements were not repainted in the second generation.

In the third generation, the newel post was painted with the same coarsely ground olive green paint (3a), and oil varnish (3b), that was used in the central block and east passage. However, while the newel was olive-green the balusters and stringers were painted red-brown and varnished. This polychromy was carried into the second-floor passage and rooms (see following sections). In the fourth generation, the newel was again painted green and varnished, but the balusters and stringers were painted a bright blue. This blue paint was also found throughout the second floor of the house, but not the first.

The lower stringer paint history began with a shellac sealant and a thin red-brown paint that does not seem to be the red-brown primer but appears to align with the third generation red-brown paint on the balusters and stringers. This suggests that the lower stringer is a later addition.

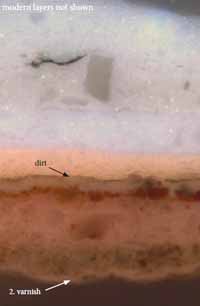

A thick layer of dirt was found on the surface of the stair riser, followed by a few layers of paint, all of which appear to date from the mid-19th century or later. This evidence suggests that the risers were originally unpainted, and remained so for at least half a century, if not longer.

59| Generation | Layer | Description | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 6a | white on trim, light brown on south door leaf | light brown also seen in central block and east passage |

| 5 | 5b | varnish with dim autofluorescence, (possibly oil bound) | also seen in central block and east passage |

| 5a | resinous light brown paint on trim and door leaves | also seen in central block and east passage | |

| 4 | 4b | varnish with dim autofluorescence (possibly oil bound) | very thin, not seen in all samples |

| 4a | olive-green paint on newel, light blue paint on balusters and stringers | seen on all woodwork in this room, as well as central block and east passage | |

| 3 | 3b | varnish with dim autofluorescence (possibly oil bound) | very thin layer |

| 3a | coarsely ground olive-green paint on newel, red-brown on balusters and stringers | olive-green paint also seen on woodwork in central block and east passage. Lower stringer may have been replaced at this time. | |

| 2 | 2 | tan-colored paint | only seen on half baluster |

| 1 | 1c | oil-bound tan-colored paint made with lead white and yellow ochre | seen on all staircase elements, same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

| 1b | thin red-brown primer | seen on all staircase elements, same chronology seen throughout house in first generation | |

| 1a | shellac sealant on wood substrate | seen on all staircase elements, same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

Staircase sample location photographs (*indicates sample discussed in report)

Staircase

Sample FH 34: Newel post, north face

FH 34 (early layers only), visible light, 200x

FH 34 (early layers only), visible light, 200x

FH 34 (early layers only), UV light, 200x

FH 34 (early layers only), UV light, 200x

FH 34 (early layers only), visible light, 200x

FH 34 (early layers only), visible light, 200x

FH 34 (early layers only), UV light, 200x

FH 34 (early layers only), UV light, 200x

Generation 2, the tan paint, is missing from this sample. it is possible that the stairway was simply not repainted during this generation.

Sample FH 36: Staircase, first 1/2 baluster attached to newel at center of stair winding

FH 36 (early layers only), visible light, 200x

FH 36 (early layers only), visible light, 200x

FH 36 (early layers only), UV light, 200x

FH 36 (early layers only), UV light, 200x

The first two tan paint generations are the same as those seen in the rest of the house. The third generation red-brown paint seen here in the balusters aligns with the olive-green paint on the newel and other east passage woodwork, as well as the earliest red-brown on the lower stringer (FH 37, p. 65). This third generation also aligns with the red-brown door leaves and verdigris green trim on the second floor passage.

Sample FH 35: Staircase, south (outer) face of upper stringer at edge of bead

FH 35 (early layers only), visible light, 200x

FH 35 (early layers only), visible light, 200x

FH 35 (early layers only), UV light, 200x

FH 35 (early layers only), UV light, 200x

Generation 2 cream paint is missing from this sample. It is also missing from the sample taken from the newel post (FH 34, p. 61).

Comparison of this sample with the staircase sample group suggests that in the third generation the balusters and stringers were red-brown while the newel post was olive-green.

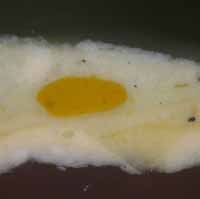

Sample FH 33: Staircase, fourth stair riser, adjoining newel and immediately below the tread

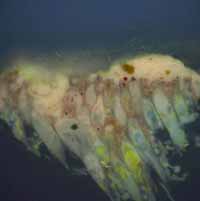

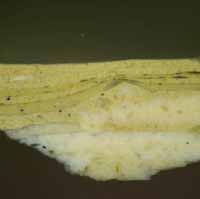

FH 33 (wood substrate), visible light, 400x

FH 33 (wood substrate), visible light, 400x

FH 33 (wood substrate), UV light, 400x

FH 33 (wood substrate), UV light, 400x

A thick layer of dirt was present on the surface of the stair riser, followed by very few layers of paint, all of which appear to date from the mid-19th century or later. This evidence suggests that the risers were originally unpainted, and remained so for at least half a century, if not longer.

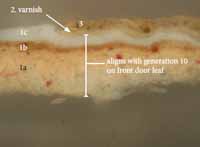

Sample FH 37: Staircase, stringer set against east and north partitions, upper bead above 4th step

The red primer applied to the staircase lower stringer is not the same as the first-period red primer seen on the woodwork throughout the house, which is much lighter in color (compare to FH 34, newel post, p. 61). However, this red layer is more visually similar to the first generation red-brown paint found on the baseboards in the first-floor west room (FH 16, p. 16). Furthermore, the red-brown paint seen here is visually similar to the third generation red-brown paint found on the staircase baluster (FH 36, p. 62), suggesting that this stringer may have been a later addition. This theory is further confirmed by the presence of fewer paint layers on the stringer, most of which consist of paints with well-ground, evenly dispersed pigment particles in non-fluorescent matrix, as seen in modern, industrially-prepared paints.

Second-floor Passage

Finnie House, second-floor plan. The second-floor passage is highlighted in red.

Finnie House, second-floor plan. The second-floor passage is highlighted in red.

General notes:

The shape of this passage has changed much over time, and the woodwork is a mix of new, original, and re-used material from other parts of the house. The architectural report notes that "all original partitions [have been] moved to new positions...originally closet in what is now new bath removed. In the north and south bedrooms a continuous, irregular joint in the flooring can be seen. This has been taken as indication of the partition that ran across the building from north to south before the house was restored." (Kocher and Dearstyne 1950, 50). Original woodwork includes the baseboards, the south window architrave, and a small section of chair rail inside of the south closet.

The south closet space is original but almost all of its associated woodwork is new. The north closet is a new space with a re-used door leaf that has been reversed (raised panels on inside). The door leaf and trim leading to the north room are original, and the door leaf to the south room is re-used from "an old closet door" (Kocher and Dearstyne 1950, 57) . The bathroom is a modern space but the door trim was apparently re-used from original trim at the top of the stair, although on-site examination found only modern paints which suggested that this trim was new.

Results:

Six samples were collected from woodwork in this space that retained substantial paint accumulations: the south window architrave (FH 54), the north closet door leaf, passage-side (FH 56) and closet-side (FH 57), the southwest room door leaf, passage-side (FH 55), and the north room door architrave (FH 59), and leaf, passage-side (FH 58).

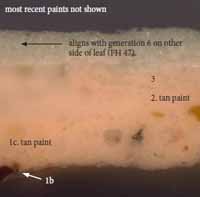

Out of this group, the south window architrave )FH 54), and the north room door leaf (FH 59), and architrave (FH 55), are known to be original to this space, so their results will be discussed first. The first and second generations are the same as those seen throughout the house, consisting of a shellac sealant (1a), red-brown primer (1b), and tan-colored paint (1c), followed by a second generation tan paint that appears to have been applied shortly thereafter.

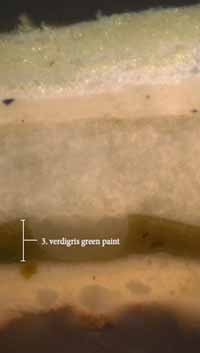

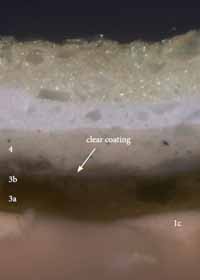

In the third generation, the trim was painted a deep green color. This layer is different from the third 67 generation olive-green paint used in the first-floor central block, east passage and staircase newel, which contained large yellow, white, red and blue pigment particles in a green matrix. By contrast, the second-floor green paint is much more finely ground and only green, white and colorless particles are seen. The layer is almost completely non-fluorescent (compared to the first-floor green which had a dim autofluorescence), suggesting that it contains verdigris, which would have lent it a deep, rich, green color. Consequently, this finish has oxidized and appears very dark, so its original color could not be determined.

The original window (FH 54), and door architrave (FH 59), also contained the first two tan generations and the third generation deep green. Comparison of these samples to the northwest room door leaf (FH 55), determined that in the third generation the door leaves were red-brown.

The south window paints aligned with the finishes in this space but also contained thick, tannish layers that were not seen elsewhere. This material was re-examined with Susan Buck who suggests it may represent an aged, 'flatted' varnish layer (June 2011). Further analysis with FTIR or GC-MS would be necessary to identify this material with confidence. In the fourth generation, a blue paint was seen on the north room door leaf, while the trim was painted white. This blue paint was also used throughout the second floor rooms and on the staircase.

The paint history of the door leaf to the southwest room (FH 55), was different from any other door in this space, or for that matter, the house. The stratigraphy begins with generation 1, a white paint that could not be directly aligned with any other paint elsewhere. This was followed by generation 2, a wood graining finish comprising a peach-colored base coat, an orange-red graining layer, and thin varnish layer. Multiple faux-wood graining and red-brown finishes follow, none of which could be aligned to any of the other door leaves in the house. The analysis was not able to determine which closet this leaf originated from (as was suggested by the 1950 architectural report). It may not be original to the house.

The north closet space is not original, but the paint evidence contained on the present door leaf is consistent with the finish history of the house, confirming that it was re-used from this building, as stated in the report. The first generation is the shellac (1a), red-brown primer (1b), and tan paint found throughout the house in this period. The second generation tan paint was found on the passage-side of the door, but this generation was not seen on the closet-side. In the next generation, both sides of the door were painted red-brown (3a) and varnished (3b), consistent with the door leaves on the second-floor passage in this period. The varnish is worn and has very little autofluorescence suggesting a high oil component. In the fourth generation, the passage-side of the door was painted light blue while the closet-side was painted white. The paint stratigraphy on the passage-side of the door is consistent with the passage-side of the northwest room door leaf (FH 58), which suggests that the present north closet door leaf originates from the second-floor.

68| Generation | Layer | Description | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 4 | white on trim, light blue on door leaves, except closet-side of north closet door leaf | same light blue also seen on stairs and on trim in second-floor north and south rooms |

| 3 | 3b | varnish (over red-brown), flatted varnish on window trim | dim autofluorescence over red-brown paint suggests oil component |

| 3a | deep green paint on trim, red-brown paint on door leaves | dark autofluorescence of green suggests verdigris | |

| 2 | 2b | clear coating with dim autofluorescence (possibly wax) | window architrave only |

| 2a | tan-colored paint | not seen on closet-side of north closet door leaf | |

| 1 | 1c | oil-bound tan-colored paint made with lead white and yellow ochre | Same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

| 1b | thin red-brown primer | Same chronology seen throughout house in first generation | |

| 1a | shellac sealant on wood substrate | Same chronology seen throughout house in first generation |

Second-floor passage sample locations (*indicates discussed in report)

69 closet door at top of stairs, closet-side

closet door at top of stairs, closet-side

Second-floor passage

Sample FH 54: south wall, window, west architrave, middle of backband

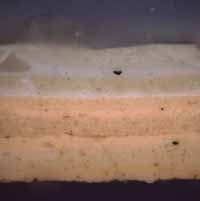

FH 54, visible light, 400x. Only early layers shown.

FH 54, visible light, 400x. Only early layers shown.

FH 54, UV light, 400x. Only early layers shown.

FH 54, UV light, 400x. Only early layers shown.

Sample FH 54 indicates that in the first and second generations the second-floor passage was painted with the same tan paints found throughout the first-floor during this period. However, the third generation green paint seen on the second floor is very different from that found on the first-floor central block and east passage.

The sample from the northwest room door architrave (FH 59, p. 72), contained a similar stratigraphy to that seen above, starting with a first generation tan paint, second generation tan, and a third generation green paint that has a dark autofluorescence, suggestive of verdigris. However, the clear coatings seen here on the window architrave (2b, 3b, and 4b), were not seen on the door architrave, suggesting that these may have been maintenance coatings or flatted varnishes that were not applied to all woodwork in the space.

The fourth generation blue paint that followed the verdigris green in the second-floor north and south rooms is absent here. In fact, it was not seen in any of the samples taken from woodwork that was known to be original to the second-floor passage. In this generation, the window architrave appears to have been painted white.

Sample FH 58: leaf of door to northwest room, passage-side, bottom left panel

Sample FH 58 indicates that the in the first and second generations, the door leaves in the second-floor passage were painted with the same tan paint that was used throughout the house. However, in the third generation, the door leaves on the second-floor passage were painted red-brown, in contrast with the wood trim which was painted a deep green made with verdigris (compare to sample FH 59, next page).

Sample FH 59: architrave of door to northwest room, lower left jamb

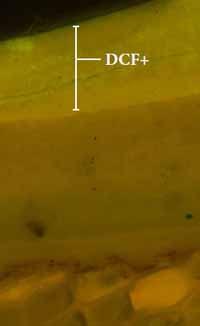

FH 59, visible light, 400x

FH 59, visible light, 400x

3b. verdigris green paint

3a. verdigris green paint

The generation 3 verdigris green paint seen here on the door architrave aligns with the third generation red-brown on the door leaf (FH 58). This same stratigraphy was also seen on the passage window architrave (FH 54).

The generation 4 white paint seen here aligns with the fourth generation blue paint on the door leaf (FH 58, p. 71).

FH 59, UV light, 400x

FH 59, UV light, 400x

2b. verdigris green paint

3a. verdigris green paint

Sample FH 56: Present closet at stair landing, door leaf (passage-side), left stile

FH 56, visible light, 400x (top and bottom)

FH 56, visible light, 400x (top and bottom)

FH 56, UV light, 400x (top and bottom)

FH 56, UV light, 400x (top and bottom)

Sample FH 57: Present closet at stair landing, door leaf (closet-side), west bottom raised panel

FH 57, visible light, 400x. Only early layers shown

FH 57, visible light, 400x. Only early layers shown

FH 57, UV light, 400x. Only early layers shown

FH 57, UV light, 400x. Only early layers shown

Unlike the other samples from this space, the second generation cream paint is missing from sample FH 57. Like the staircase, this side of the door leaf may not have been repainted in the second generation.

Two applications of the third generation red-brown paint are observed here, but other samples cast from this same sample showed only one red-brown layer, so it is likely that this area was inadvertently painted twice in the third generation, or locally retouched later.

Sample FH 55: Door leaf to southwest bedroom, passage-side, right stile

FH 55, visible light, 200x. Only early layers shown

FH 55, visible light, 200x. Only early layers shown

FH 55, UV light, 200x. Only early layers shown

FH 55, UV light, 200x. Only early layers shown

FH 55, visible light, 400x. Only early layers shown

FH 55, visible light, 400x. Only early layers shown

FH 55, UV light, 400x. Only early layers shown

FH 55, UV light, 400x. Only early layers shown

This paint history does not align with any other finishes seen elsewhere on the second floor or in the house. This door is most likely not original to the building.

Second floor, Northwest room

Finnie House, second-floor plan.

Finnie House, second-floor plan.

The present northwest room is highlighted in red.

General notes:

As mentioned previously, the arrangement of the second floor has changed much over time. The original partitions were moved and the present bathroom was originally part of this room (Chappell, sample memo, Appendix C). The entrance door trim and leaf in this room are relocated from the original partition, as is the door leaf to the closet in the northeast corner, although this closet is not original to the room (Kocher and Dearstyne 1950, 49). The window architraves are original, but the sash is new. The mantel in this room is also new, as is most of the chair rail.

Results: