Cross-section Microscopy Analysis of Interior Paints: Orrell House (Block 2, Building 38), Williamsburg, VirginiaCross-section Microscopy Analysis Report: Orrell House, Interior Finishes, Block 2, Building 38

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1749

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2013

CROSS-SECTION MICROSCOPY ANALYSIS REPORT

ORRELL HOUSE, INTERIOR FINISHES

Block 2, Building 38

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION

WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA

| Purpose | 3 |

| History | 3 |

| Previous Research | 3 |

| Procedures | 3 |

| Results | 4 |

| Front Passage | 5 |

| Binding Media Analysis | 23 |

| Rear Passage (Present Kitchen) | 25 |

| Second Floor Passage | 31 |

| First-Floor Front (North) Room | 39 |

| Binding Media Analysis | 58 |

| First-Floor Rear (South) Room | 60 |

| Binding Media Analysis | 73 |

| Pigment Identification | 77 |

| Color Matching | 86 |

| Conclusions | 90 |

| References | 91 |

| Appendix A. Procedures | 92 |

| Appendix B. Sample Memo | 94 |

| Appendix C. Chappell Field Notes 2012 | 96 |

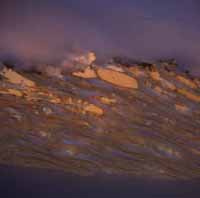

Orrell House, Block 2, Building 38; north elevation

Orrell House, Block 2, Building 38; north elevation

| Structure: | Orrell House, Block 2, Building 38 |

|---|---|

| Requested by: | Edward Chappell, Roberts Director of Architectural and Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation |

| Analyzed by: | Kirsten Travers, Paint Analyst, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation |

| Consulted: | Susan L. Buck, PhD., Conservator and Paint Analyst, Williamsburg, Virginia |

| Date submitted: | December 2012 |

Purpose:

The goal of this project was to use cross-section microscopy techniques to explore the early interior paint history of the Orrell House, to better understand the arrangement of spaces and finish in the colonial period. Fluorochrome staining was used to characterize the binding media of the earliest paints, and polarized light microscopy techniques were used to identify their pigment composition. Early colors were measured with a colorimeter/microscope to provide the closest commercial color match.

History:

Very little is known about the 18th-century history of the Orrell House, but a house on this lot does appear on the Frenchman's map of 1782, and Whiffen (1984), suggests the house dates from c.1775 - 1800. Restoration was carried out from April 1929 to January 1931 (Moorehead 1932). According to the 1932 architectural report, much of the interior woodwork is original or early, including many of the chair rails, door leafs, baseboards, and door and window trim (more detail in Appendix C). All of the plaster dates to the restoration, and was not sampled.

Previous Research:

In 2011, twenty samples from the Orrell House exterior (collected by Natasha Loeblich) were investigated for paint evidence, but no 18th-century finishes were found (Travers, 2011). In all of the samples, the wood substrate was aged, soiled, and disrupted, suggesting that the surfaces had been allowed to weather for an extended period of time before the extant paints were applied.

Procedures:

On March 16, 2012, thirty-seven paint samples were removed from the Orrell House interior by Kirsten Travers, accompanied by Edward Chappell (Director of Architectural and Archaeological Research). On site, a monocular 30x microscope was used to examine the painted surfaces to determine the most appropriate areas for sampling. A microscalpel was used to remove the samples, and sampling locations were recorded and photographed. Samples were labeled and stored in small, individual Ziploc bags for transport. 4 All samples were given the prefix "OH", and numbered according to the order in which they were collected, starting at "OH 21", since OH 1- OH 20 correspond to a group of exterior samples collected in 2009. See Appendix B for a list of all sample locations.

In the laboratory, the samples were examined with a stereomicroscope under low power magnification (5x to 50x), to identify those that contained the most paint evidence and would therefore be the best candidates for cross-section microscopy. Uncast portions were retained for future examination and analysis, if necessary. The best candidates were cast in resin cubes and sanded and polished to expose the cross-section surface for microscopic examination. Please see Appendix A for sample preparation details.

The cross-section samples were examined and digitally photographed in reflected visible and ultraviolet light conditions at 100x to 400x magnifications. By comparing the resulting photomicrographs, finish generations could be interpreted based on physical characteristics such as color, texture, thickness, presence of dirt layers and extent of surface deterioration.

Results:

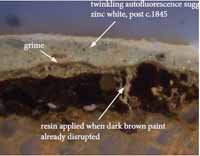

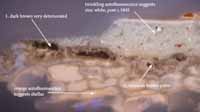

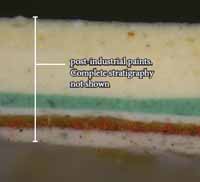

The investigation found good early paint evidence that sheds light on our understanding of the Orrell House. In each space, the first two paint generations are extensively disrupted before being re-painted with a zinc white paint that dates to the mid-19th century or later. This suggests the interior woodwork was painted infrequently from the late 18th century into the mid-1800s.

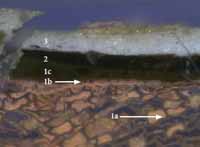

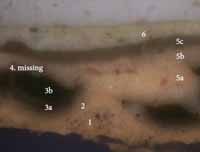

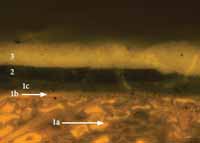

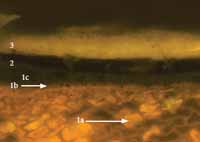

The results are organized according to space- the front passage is discussed first, followed by the rear passage (now a kitchenette), the second-floor woodwork, the first-floor front room, and the first-floor rear room. Paint stratigraphies have been annotated according to finish generation. For instance, a primer, paint layer, and varnish may represent one finish generation and are all given the same number, but differentiated with lowercase letters (1a, 1b, 1c, etc.). Since many samples contained redundant evidence, only the most relevant cross-section photomicrographs are presented in this report. The analytical results and pertinent observations are discussed adjacent to the photomicrographs. The results are interpreted in the conclusion, and all raw photomicrographs can be found in the appendix at the end of this report.

Front Passage:

Eleven samples were collected from the front passage woodwork, including the stair:

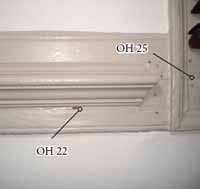

| OH 21 | West wall, backboard of chair rail, bottom bead, 27" out from south wall |

| OH 22 | East wall, backboard of chair rail, under bolection, 40" out from north wall |

| OH 23 | North wall, backboard of chair rail, 2" west of front door architrave |

| OH 24 | Entrance door architrave, left jamb, backband, 13" up from floor |

| OH 31 | West wall, door leaf to living room, bottom right panel, bottom right edge |

| OH 25 | East wall, window architrave, left jamb |

| OH 44 | West wall, door architrave to living room, left jamb, center fascia, 24" up from floor |

| OH 45 | South wall, baseboard of east-west partition leading to kitchenette, west side of door |

| OH 26 | Stair, landing, third baluster up from newel post, top of shaft |

| OH 27 | Stair, landing, newel post, south face, just under handrail |

| OH 28 | Stair, handrail fascia, just above sample OH 27 |

Description/Examination:

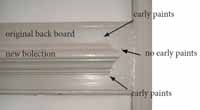

E. Chappell noted that most of the stair is original, as is the single architrave to the entrance door (although the leaf is 20th century). The double architrave to the front room from the passage is also early, and matches the double architrave in the adjacent front-right (northwest) room leading to the rear-right (southwest) room. The door leaf between the passage and the front room appears old but much reworked.

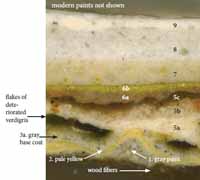

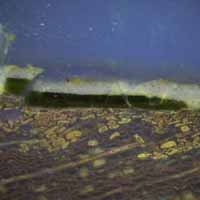

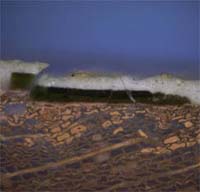

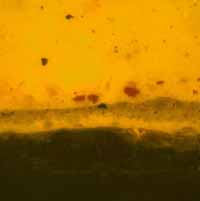

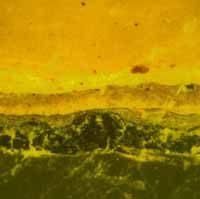

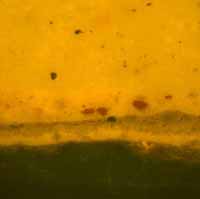

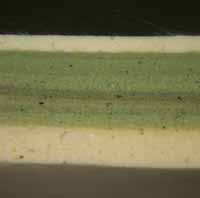

In this space, the chair rail back boards are original, but the bolections were added during the restoration. On-site, the chair rails were examined by E. Chappell, who suggested making micro-excavations at strategic locations to determine if the present bolections were modeled after the originals. Numerous micro-excavations suggested that the earliest paint on the back boards was a gray base coat with a verdigris green finish (confirmed via cross-section microscopy).

Front passage, west wall, chair rail

Front passage, west wall, chair rail

Early verdigris-based paints were seen both above and below the bolection, but there were no verdigris-based paints on the section that would have been covered by a longer applied molding, suggesting that the present bolections might be shorter than the originals. This was confirmed repeatedly in other locations in this space.

6On-site micro-excavations found the first generation verdigris-green finish on all of the chair rails, including the chair rail on the south wall (leading to the present kitchenette). This dividing wall was believed to date to the restoration (the Architectural Report is vague on this point), so this finding suggests that this wall is original or that original chair rails from elsewhere in the space were re-used on this wall when it was constructed in the early 20th century.

Summary of Analytical Results:

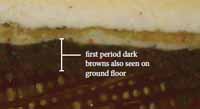

The chair rails (OH 21), door architraves (OH 24, OH 44), door leaf (OH 31), and stair samples (OH 26, OH 27, and OH 28) contained good early paint evidence from which the early decorative history of this space could be extrapolated. The results suggest that in the first period, the front passage was painted in a polychrome scheme consisting of verdigris-green trim with dark brown stair and door leafs. This scheme was repainted once (generation 2), and appears to have been exposed for a very long period of time, allowing it to crack and wear down, before being repainted with a zinc-based paint that dates to the mid-19th century at the earliest.

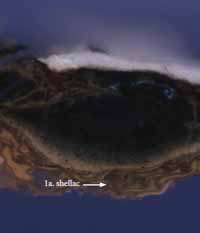

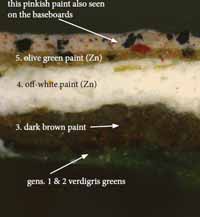

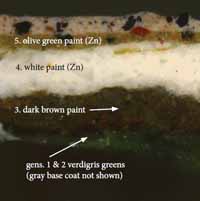

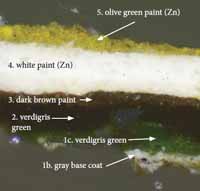

In the first generation, the chair rails, door architraves, and tall stair newel post on the south wall were sealed with shellac (generation 1a) and painted with a gray base coat (generation 1b) made with lead white, carbon black, and possibly a small amount of red earth pigment (PLM) in an oil medium (DCF+).This was finished with a green verdigris-based finish (1c). This finish appears to be an opaque bright green paint in cross-section containing large, coarse particles of verdigris pigment. However, actual particles of verdigris were not found via PLM, which identified only a green copper resinate glaze with lead white pigment. (For clarity in this report, this finish (generation 1c), is designated a verdigris paint). During this same period, the door leaves and stair (with the exception of the newel) were painted dark brown with a coarsely ground paint made with red earth and carbon black pigments (PLM) in an oil medium (DCF+).

In generation two, a deeper verdigris green glaze (PLM identified copper resinate glaze only, no verdigris pigment particles. In addition, no verdigris particles were observed in the cross-section). This glaze was applied over the previous green on the trim and stair newel, and a resinous dark brown paint was applied over the previous dark brown on the door leaves and stair. The surface of this paint is very disrupted and cracked, suggesting it was exposed for a very long period of time.

In generation three, the door architraves were painted dark brown and the leaves were faux-grained in a reddish-colored wood in imitation of mahogany. The rest of the woodwork in the passage was not painted. Generation four is a zinc white paint on the trim (identified by its bright "twinkling" particles of zinc white pigment in UV light), which must date to c.1845 or later, when this pigment was introduced commercially. In this period, the door leaves were again faux-grained, in imitation of a lighter wood, possibly oak.

On-site micro-excavations did not find 18th-century paints on the east wall window architrave and baseboards. However, some early finish evidence was found, so it is possible that these were early additions or that the first period finishes were lost from these surfaces. The samples were so disrupted that it was not possible to align the finishes to determine an installation period, if these were indeed additions.

Front Passage, Sample Locations:

8 West wall, door leaf to front-right (northwest) room

West wall, door leaf to front-right (northwest) room

West wall, door architrave to front-right (northwest) room

West wall, door architrave to front-right (northwest) room

Stair at landing between 1st and 2nd floors

Stair at landing between 1st and 2nd floors

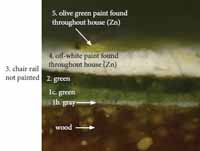

Chair rails

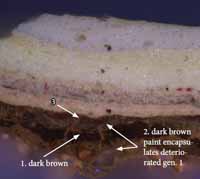

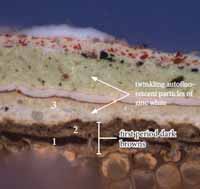

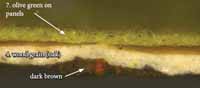

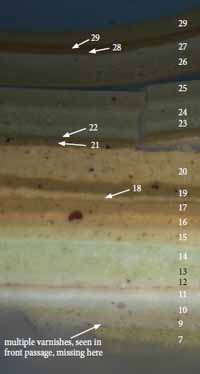

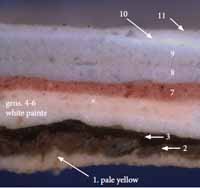

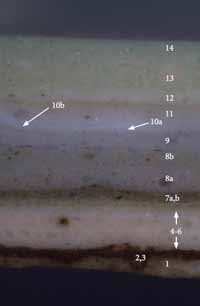

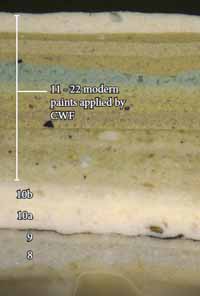

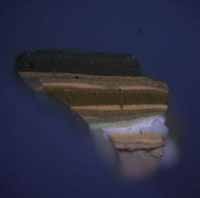

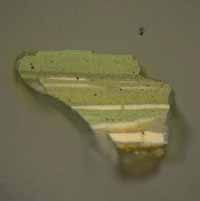

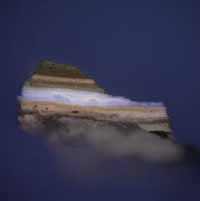

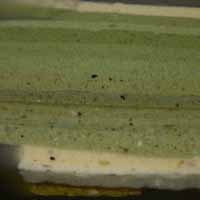

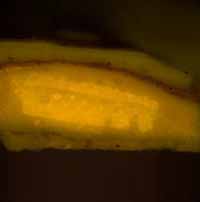

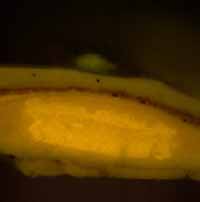

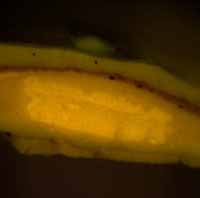

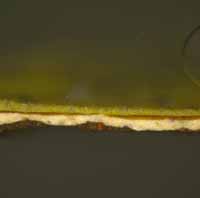

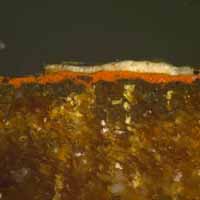

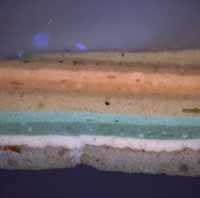

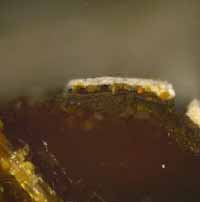

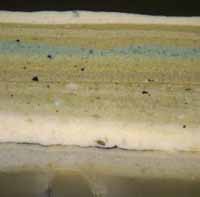

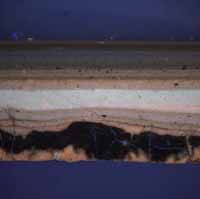

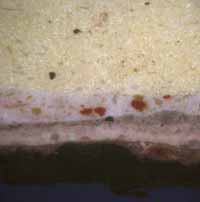

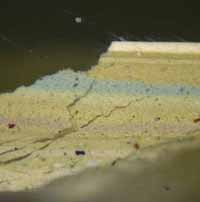

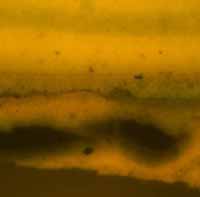

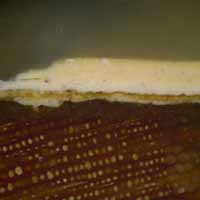

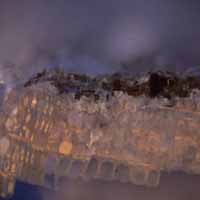

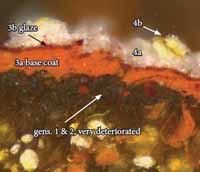

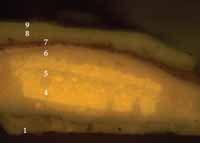

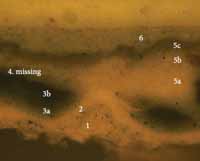

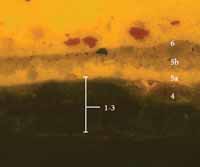

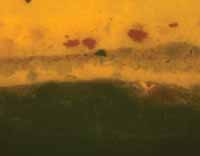

The first generation finish on the chair rails was a shellac sealant (1a, suggested by the orange-colored autofluorescence in the wood), a thin gray base paint (1b), and an opaque bright green paint made with coarsely ground verdigris pigments (1c, suggested by its lack of autofluorescence).

In the next generation, another verdigris green finish was applied, this time a glaze of a much deeper color (2). Although it is in relatively good condition in sample OH 21, this finish was very disrupted in most samples, suggesting it was exposed for a very long period of time. These same early finishes were also found on the door architraves in the front passage (sample OH 24).

In generation three, only the door architraves were painted dark brown, and the door leaves were faux-grained in imitation of a reddish wood, possibly mahogany. Therefore, this sample from the chair rail is missing the third generation paint.

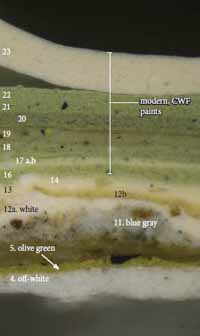

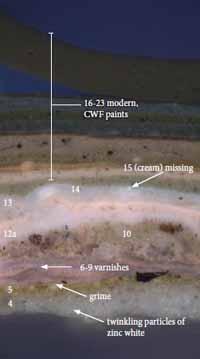

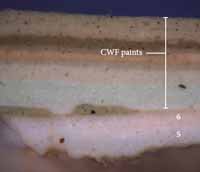

Generation four is an off-white paint that contains zinc white pigment, suggested by the "twinkling" autofluorescent particles seen in the UV image (Travers 2011). This pigment was not commercially available before c.1845 (Gettens and Stout, 177). Therefore, generation 2 (the deep green verdigris finish), would have been exposed until at least the mid-19th century, when the zinc-based paint was applied. This could explain the severe deterioration of the verdigris finish in the other samples.

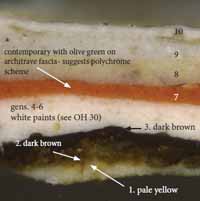

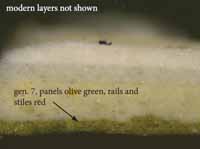

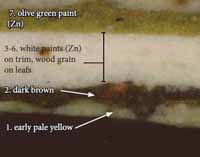

The olive-green zinc-based paint at the top of this sample fragment was also seen throughout the house. It appears to belong to a green and red polychrome scheme, and most likely dates to the late 19th-century.

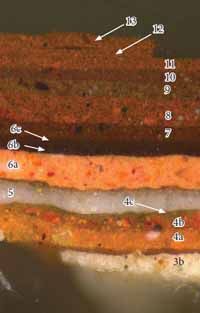

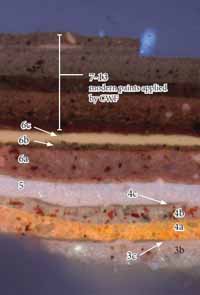

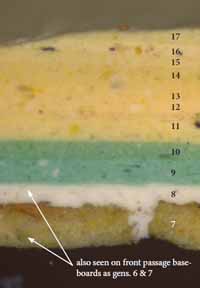

11The paint history of the front passage chair rails continues with an olive green paint in generation 5. This paint also contains bright, twinkling particles of zinc white, and was seen in other samples taken throughout the house. This is followed by approximately four generations of very disrupted varnishes (generations 6-9). The thin layer of grime on the surface of the olive green paint suggests this color was exposed for a long time and then varnished repeatedly rather than being repainted. However, these varnishes were not seen in all samples.

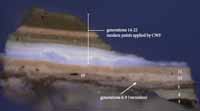

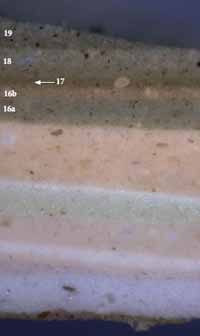

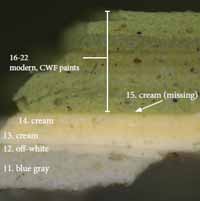

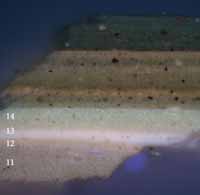

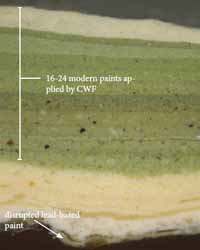

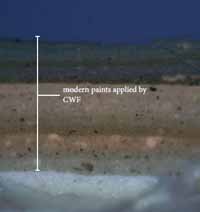

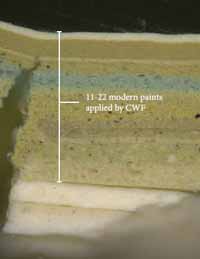

Generation 11 is a blue-gray paint that contains zinc white, followed by generation 12a, a white paint with a varnish coating (12b). Generations 13 and 14 are a cream-colored paints that also contain zinc white. The rest of the paints in this sample are finely ground coatings, sometimes with a dim autofluorescence, suggesting these are modern paints that were most likely applied by CWF in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Door architrave to front entrance

The early paint history of the door architrave (a single architrave) is the same as the front passage chair rails, starting with a shellac sealant (1a), a gray base coat (1b), and a coarsely ground bright green paint made with coarsely ground verdigris pigment (1c).

Generation 2, the deep green verdigris glaze, appears to be missing from this sample. Generation 3 is a dark brown paint that was also seen on the door architrave to the living room (OH 44), but not on the chair rails. Generation 4 is a white paint that contains zinc white pigment, dating it to the mid-19th century or later.

The remainder of the stratigraphy is found on the next page, and aligns with that found on the chair rails.

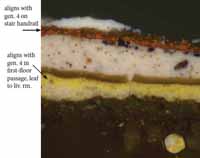

13Door architrave to front room

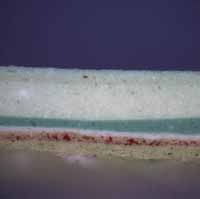

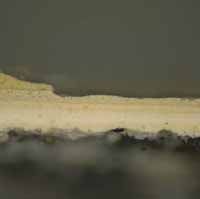

The architrave to the front room (a double architrave), contains the same first two generations as the chair rails and the entrance door architrave, consisting of a gray base coat followed by a bright green verdigris paint. Generation 2 is a deep green glaze made with verdigris.

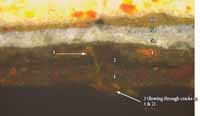

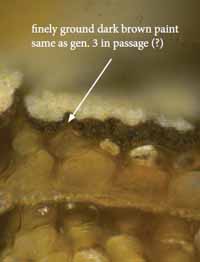

In generation 3, the door architraves were painted dark brown. It does not appear to be the same as the dark brown paints on the stair (generations 1 and 2), which is very coarsely ground and contains large red and orange particles. By contrast, the generation 3 dark brown paint seen here is thinner and much more finely ground. It is seen to flow into pre-existing cracks in the generation 2 verdigris glaze, suggesting it was applied when the previous finish was very deteriorated.

The fourth generation is a white paint that contains zinc white, as does generation 5, the olive green paint seen throughout the house. Both of these paints would date to the mid-19th century at the earliest.

The rest of the stratigraphy is shown on the next page.

15The door architrave leading from the passage to the front room contained up to 19 generations of paint, although the most recent layers are missing from the sample fragment shown above.

These later paints align with those found on the chair rails and entrance door architrave.

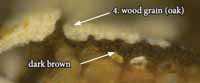

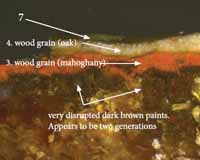

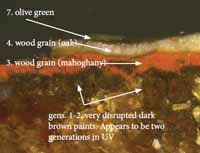

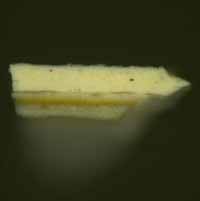

Door leaf to front room

Approximately 22 generations of paint were identified on the door leaf to the front room. The leafs have a different paint history from the chair rails and architraves in the passage, but they were painted similarly to the stairs (see following pages).

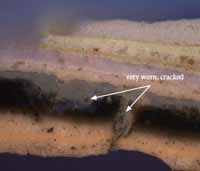

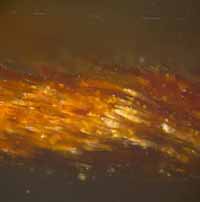

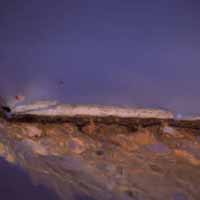

The first generation is a dark brown paint that is very coarsely ground and contains large particles of orange and red pigment. This paint has a very dark autofluorescence. It is heavily worn and cracked, suggesting it was exposed for a long period of time. Generation 2 is another dark brown paint, possibly with a resinous media, based on its somewhat brighter autofluorescence. This paint flows into pre-existing cracks in generation 1, suggesting the latter was already quite 17 deteriorated when it was repainted for the first time.

Generation 3 is a faux-wood graining finish, consisting of an orange-red base coat (3a), and a thin red graining layer (3b), possibly in imitation of a red wood such as mahogany.

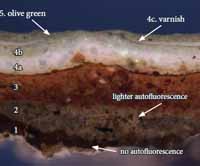

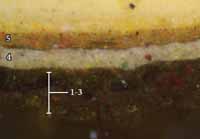

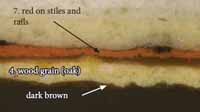

Generation 4 is another faux-wood graining finish consisting of a yellow base coat (4a), a thin orange-brown graining layer (4b), and a clear varnish (4c), possibly in imitation of a lighter colored wood such as oak. This paint was found to contain "twinkling" autofluorescent particles of zinc white, which dates this finish to c.1845 or later. Generation 5 is the olive green paint that was seen throughout the house and may date to the late 19th-century.

Passage, door leaf to front room

Passage, door leaf to front room

OH 31a, visible light, 200x

Front right room, door leaf to rear room

Front right room, door leaf to rear room

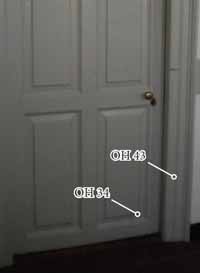

OH 34, visible light, 200x

As shown above, generations 1-5 on the door leaf from the passage to the front room (OH 31) align with those on the leaf in the front room leading to the rear room (OH 34). This suggests these leafs are contemporary.

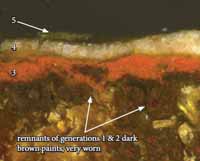

Stair, baluster

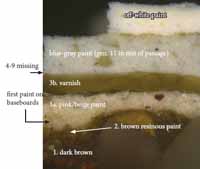

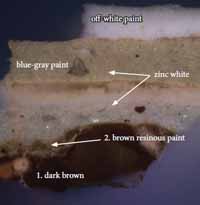

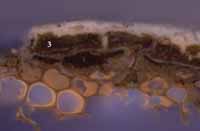

There was no verdigris found on the stair. Instead, the earliest paints appear to be dark browns that would have matched the door leaves in generations 1 and 2. The first generation is a coarsely ground dark brown paint which contains large particles of red, yellow, and brown pigments. This paint was exposed for a very long period of time, evidenced by the deep cracks in its surface. The second generation is a resinous brown paint, whose orange autofluorescence suggests it may be shellac-based. The grime layer on top of this finish suggests that it, too, was exposed for a long period of time. The third generation is a pinkish-beige zinc-based paint that would date to the 19th-century at the earliest. This appears to be the same as the first generation paint applied to the front passage baseboard (OH 45, p.22), confirming that the baseboard is comparatively later, or that the earliest paints are missing.

Stair, newel post

The early finishes on the newel post are the same as those on the baluster (previous page). The first generation is dark brown paint that was exposed for a long period of time and allowed to crack and wear down. The next generation is a resinous brown paint that flowed into pre-existing cracks in the first generation. The grime on the surface of generation 2 suggests it was also exposed for a long period of time. The third generation is a zinc-based paint that would date to the mid-19th century at the earliest.

Stair, handrail

The handrail shares the same early finish history as the newel post and balusters. The first generation is a very deteriorated dark brown paint. The second generation is a very grimy resinous brown paint that has flowed around and under the fragments of earlier paint. The third generation is a zinc-based paint that would date to the mid-19th century at the earliest.

The rest of the handrail paint history is shown on the following page.

21Approximately thirteen paint generations on the handrail were identified (the first three generations are shown on the previous page).

The evidence suggests that after the fourth generation (mid-19th century), the handrail was usually picked out in deep red finishes and dark brown colors, in contrast to the rest of the passage trim (which was white, cream, or greenish-gray). The remaining paint history of the handrail includes a fourth generation decorative finish, possibly a wood grain, consisting of a deep red-orange base coat (4a), a dark red transparent graining layer (4b), and a varnish (4c).

Generation 5 is a zinc-based paint. The layer of grime on the surface suggests this was exposed for some time before being repainted. Generation 6 is another wood graining finish consisting of a red-orange base coat (6a), a dark brown graining layer (6b) and a resinous coating (6c), possibly shellac, based on its orange autofluorescence. Generations 7-13 are finely ground dark brown paints and appear to be industrially prepared paints that were applied by CWF.

Baseboards

There were no 18th-century paints on the baseboard. The earliest paint contains "twinkling" autofluorescent particles of zinc white, which post-dates c.1845. This generation appears to be the same pinkish-beige paint that is identified as generation 3 on the stair (see pp. 18-20). However, sample OH 45 was taken from an area that had the most paint evidence, following extensive in situ examination. This would indicate that even baseboard areas that have significant paint accumulations do not contain 18th-century finishes.

These findings could suggest that the baseboard is an early addition; or that the first-period finishes have been removed from the baseboard through abrasion and wear.

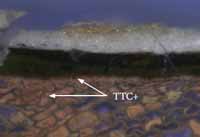

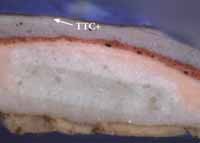

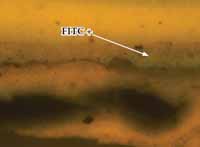

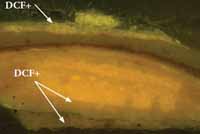

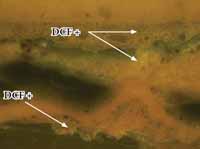

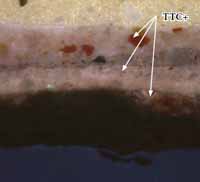

Binding media analysis

The earliest generations in sample OH 21 (front passage, chair rail), were stained with biological fluorochromes to characterize the binding media. The results are summarized in the table below.

| Generation | Description | DCF rxn | FITC rxn | TTC rxn | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | white paint | + | - | - | oil bound |

| 2 | verdigris paint or glaze | weak + | - | - | may be a resinous glaze, with some oil component |

| 1c | verdigris paint | + | - | - | oil bound |

| 1b | gray base coat | + | - | + | oil bound, with carbohydrate component, possibly gum to aid pigment dispersal |

| 1a | shellac | + | - | + | DCF+ may result from oil medium above, or oil may have been added to shellac |

DCF stain for lipids (oils)

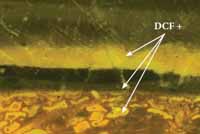

OH 21, B-2A filter, 200x. Before DCF stain.

OH 21, B-2A filter, 200x. Before DCF stain.

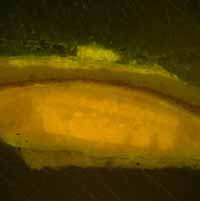

OH 21, B-2A filter, 200x. DCF reaction.

OH 21, B-2A filter, 200x. DCF reaction.

The early paints in sample OH 21 were stained with DCF to tag for the presence of lipids (oils). Positive reactions (a yellow-green fluorescence) were observed throughout the sample.

FITC stain for proteins

OH 21, B-2A filter, 200x. Before FITC stain.

OH 21, B-2A filter, 200x. Before FITC stain.

OH 21, B-2A filter, 200x. FITC reaction.

OH 21, B-2A filter, 200x. FITC reaction.

The early paints in sample OH 21 were stained with TTC to tag for the presence of carbohydrates. Positive reactions (a red-brown color) were observed in the shellac sealant (1a) and the gray base coat (1b). These results suggest that these coatings might have contained a gum additive.

First floor, current kitchenette/pantry (rear passage)

Three samples were collected from the woodwork in the present kitchenette/pantry (rear passage) space:

| OH 36 | West wall, door architrave to bedroom #1, left jamb, inner fascia, 19" up from floor |

| OH 37 | West wall, door leaf to bedroom #1, left stile, 28" up from floor |

| OH 38 | West wall, door leaf to bedroom #1, lower left panel, upper left corner |

Description/Observations:

Most of the woodwork in this space is new, but samples were taken from the door leaf and architrave leading to the rear room, which had substantial paint accumulations and appeared to be original. This double architrave that leads from the kitchenette/pantry (rear passage) to the rear room matches the double architrave on the same wall that leads from the front passage to the front room. This suggested to E. Chappell that the present front and rear passages might have been originally continuous and this space was sub-divided to create the kitchenette in the 20th century. The door leaf presently leading from the rear passage to the rear room appears to be reversed, as the passage-side has the inferior construction. The room-side of the same leaf has been crudely re-crafted with a replaced stile and panel, and cyma moldings replacing some originals (Chappell, 2012, sample memo).

Summary of Analytical Results:

The early finish history of the door architrave to the rear room (OH 36) is the same as that found on the door architrave from the passage to the front room on the same wall (OH 44), which suggests that the passage did originally extend to the rear wall (see below for comparison), and that the present dividing wall was a restoration-era addition. However, this theory is complicated by the fact that the first period verdigris was found on the chair rails on the partition wall, which would suggest that this wall is first period, and that the passage was originally split into two separate spaces. The reason for this discrepancy is not clear. One theory is that the chair rails were re-used from the passage.

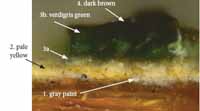

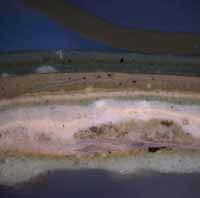

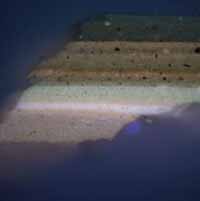

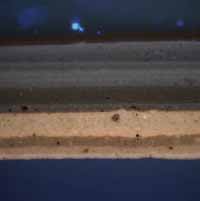

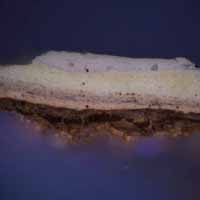

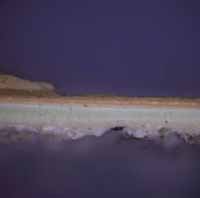

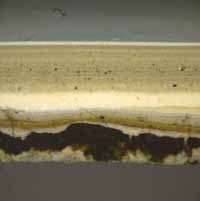

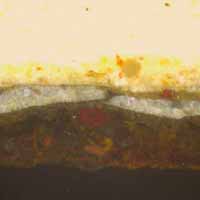

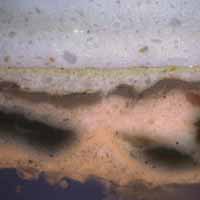

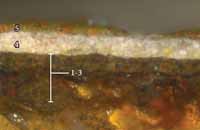

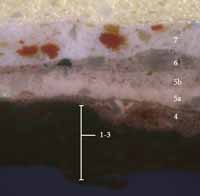

The first generation on the door architrave in the rear passage (see below, left), consists of a shellac sealant (1a), a gray base coat (1b), and a coarsely ground verdigris-green paint (1c). Generation 2 is a deep verdigris-green glaze that is very deteriorated and cracked, suggesting it was exposed for a long period of time (when the third generation dark brown paint was applied to the door architraves, it flowed into pre-existing cracks in the earlier finishes). Generation 4 is a white paint that contains zinc white, which dates this paint to c.1845 or later.

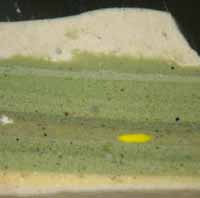

Kitchenette, door architrave to rear room

Kitchenette, door architrave to rear room

OH 36b, visible light, 200x

Front passage, door architrave to front room

Front passage, door architrave to front room

OH 44b, visible light, 200x

Furthermore, the paint evidence confirmed that the door leaf leading from the rear passage to the rear room is reversed: the paints on the present passage-side (inferior construction) align with those found on the interior of the room; while the paints on the present room-side align with those in the passage (see p. 30 for further discussion)

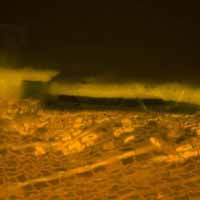

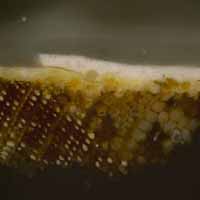

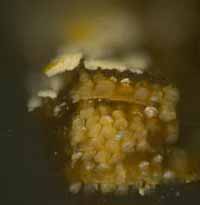

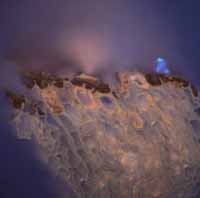

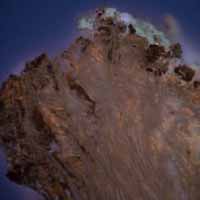

Door architrave to rear room

The early paint history of the door architrave leading from the current kitchenette to the rear room is the same as the early paint history of the door architrave leading from the passage to the front room (sample OH 44), on this same wall. The first generation is a shellac sealant (1a), a gray base coat (1b), and a verdigris-green paint (1c). This is followed by a second generation deep verdigris-green glaze (2), which has deep cracks in its surface that extend all the way down to the substrate, suggesting it was exposed for a very long period of time. The third generation dark brown paint is seen to flow into these cracks and deposits on the wood. The rest of the stratigraphy is shown on the next page.

28At least seventeen generations of paint were found on the door architrave to the rear room from the present kitchenette.

Generations 9 and 10 are 20th-century deep blue-green paints that were not seen on the sample taken from the door architrave to the front room, which would reflect the more modern period when the front and rear passage were treated as separate spaces.

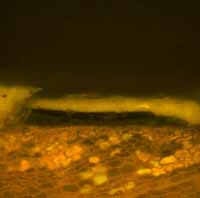

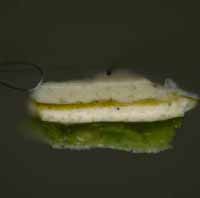

Door leaf to rear room (lower left panel)

This paint history of the passage-side of the door aligns with the leaves from the rear room, not the passage. Furthermore, the paint history of the present room-side aligns with the passage finishes. This confirms that the leaf is reversed from its original orientation (see next page for further images and discussion).

Generations 1-3 are very degraded dark brown paints. Generation 4 is a pink-beige paint that contains zinc white pigment, which post-dates this paint to c.1845 or later. Generation 5 is an olive green paint that was found throughout the house and most likely dates to the late-19th century.

30 Rear room, room-side of leaf to passage

Rear room, room-side of leaf to passage

OH 39, visible light, 200x

Passage, door leaf to front room

Passage, door leaf to front room

OH 31a, visible light, 200x

As shown in the two photomicrographs above, the paint history of the present room-side of the rear room passage door leaf (OH 39), is the same as that found on the door leaf leading to the front room from the front passage (OH 31). This confirms the on-site observation that the rear room door leaf is reversed from its original orientation.

Passage, door leaf to rear room

Passage, door leaf to rear room

OH 38c, visible light, 200x

Rear bedroom, door leaf to front room

Rear bedroom, door leaf to front room

OH 40a, visible light, 200x

Further proof confirming that this door leaf is reversed is provided by comparing the paints on the present passage-side (OH 38), to the paint history from the door leaf to the front room from the rear room (OH 40). Generations 1-5 clearly align, suggesting this side of the leaf originally faced the rear room interior.

Second floor, passage

Six samples were collected from the woodwork in the second-floor passage:

| OH 52 | Small linen closet, door leaf, passage-side, edge of lower R panel |

| OH 53 | Door leaf to SE chamber (bedroom #2), bottom R panel, underside of bottom R corner |

| OH 54 | Door surround to SE chamber (bedroom #2), left jamb, 12" from floor |

| OH 55 | Baseboard, top of stair landing, adjacent to entrance to SE chamber |

| OH 56 | Door architrave to SW chamber (bedroom #3), fascia, 20" from floor |

| OH 57 | Door leaf to SW chamber (bedroom #3), lower L panel, lower R corner |

Summary of Analytical Results:

The paint evidence in the second-floor passage was very fragmentary. This confirmed the in-situ observation that very little paint evidence survived on this floor.

Remnants of the same first generation dark brown paints used on the stairs and the door architraves in the first-floor passage were seen on some elements on the second floor, notably the small linen closet door leaf (OH 52), the door leaf to the southeast chamber (OH 53), the baseboard at the stair landing (OH 55), and the door leaf to the southwest chamber (OH 57). There were no early verdigris finishes found, as on the first floor. In addition, none of the door architraves (OH 54, OH 56), contained any early paint evidence. This would suggest that in the first period, the door leaves and baseboards were painted dark brown, corresponding with the brown-painted woodwork in the passage downstairs, but the color scheme of the second-floor trim is uncertain.

Second-floor, passage, sample locations

Small linen closet, door leaf (passage-side, lower right panel)

The finish history of the door leaf to the second-floor linen closet begins with the same two generations of very deteriorated dark brown paints found on the first period stair and door leaves in the front passage (generations 1, 2). This suggests that this leaf dates to the first period.

The third generation is a faux wood graining finish consisting of a light yellow base coat, a thin red graining layer, and a clear varnish, possibly in imitation of oak. This aligns with generation 4 on the passage door leaf leading to the living room (OH 31). This paint contains zinc white pigment and would therefore date to the mid-19th century at the earliest.

Door leaf to SE chamber (bottom right panel)

Approximately twenty-five generations of paint were found on the door leaf to the southeast chamber, which begins with the same series of very deteriorated early dark brown paints used on the ground floor leafs in the first period, suggesting this leaf is original.

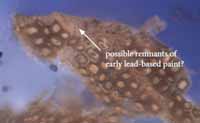

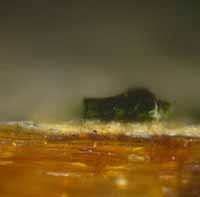

Door surround to SE chamber

Most of the extant paints on the second-floor door surround to the southeast chamber are modern. Remnants of what could be an early lead white-based paint are visible at the bottom of the sample and in the cells of the wood substrate, but this evidence is too fragmentary to make further conclusions.

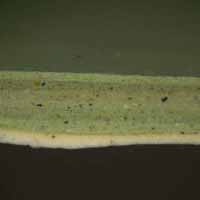

Baseboard at top landing of stairs

The baseboard at the top of the stairs appears to contain the first period dark brown paint that was also used on the stairs. This paint contains very large, coarsely ground red, orange, and black pigment particles. This evidence would suggest that this baseboard dates to the first period.

In the following generations the baseboard appears to have been painted independently of the trim, making it difficult to align the paints with other elements in this space.

Door architrave to SW chamber (bedroom #3)

Most of the extant paints on second-floor door architrave to the southwest chamber are modern paints.

There are remnants of an oilbound lead-based paint on the surface of the wood, but this evidence is not intact enough to make further conclusions.

Door leaf to SW chamber (bedroom #3, lower left panel)

The sample from the door leaf to the southwest chamber contained mostly modern paints (not shown). However, remnants of an early dark brown paint were seen in the wood cells. This paint is so disrupted it is unclear if this is the same as the first generation paint on the passage stair, or the third generation paint on the passage door architraves. However, this evidence does suggest that this leaf is early, if not original, to the house.

First floor, front-right (northwest) room:

Nine samples were collected from the front-right (northwest) room woodwork

| OH 29 | North wall, chair rail, 20" out from east wall |

| OH 30 | West wall, window architrave, right jamb, adjacent to chair rail |

| OH 32 | East wall, door leaf to passage, bottom left panel, bottom left corner |

| OH 33 | East wall, door leaf to passage, bottom left stile, 17" up from bottom |

| OH 34 | South wall, door leaf to rear room, bottom left panel, far right underside |

| OH 41 | Mantel, cap of mantel shelf, far right edge |

| OH 42 | North wall, window architrave, center of bottom frame |

| OH 43 | South wall, door architrave to rear room, right jamb, inner fascia, 12" up from floor |

| OH 46 | East wall, door architrave to passage, left jamb, backband, 25" up from floor |

Description/Observations:

The chair rails in this room have never had bolections. The door leading to the passage has a single architrave, while the door leading to the rear-right (southwest) room has a double architrave. However, the level of finish on the architraves does not align with their associated leaves. The leaf to the passage is smaller and plain on the room-side; while the leaf to the rear room is larger with superior finishes and hardware. Two theories have been suggested to explain this condition: that the door to the passage is not original to the house and was re-used from another site, or that the superior finish on the door to the rear room was deliberately intended to communicate the higher status of the front-right (northwest) room over that of the passage (E. Chappell, 2012, sample memo). It was hoped that the paint evidence would shed light on this question.

Summary of Analytical Results:

The woodwork in the front-right (northwest) room was painted up to thirty times, and some of the earliest finishes on the trim appear to align with those found on the passage trim (see next page for comparisons), with the exception of the first period finish.

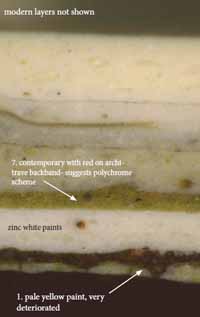

The first period finish on the trim is a shellac (generation 1a), followed by a pale yellow paint (1b) that was found on the chair rails (OH 29), the door architraves (OH 46, OH 43), and window architraves (OH 30). This paint is extremely grimy and deteriorated, suggesting it was exposed for a very long period of time. The earliest paint on the door leaf to the rear room (OH 34) is a dark brown paint that is very deteriorated, which is most likely contemporary with the pale yellow on the trim (the door leaf to the passage (OH 32, 33), seems to be missing some of its early paint on the room-side). This looks like the same dark brown paint used in other rooms in the house in this period.

In the second generation, the door leafs were re-painted dark brown, and the door architraves 40 were painted dark brown, as well. The rest of the trim in the room appears to have been left unpainted.

Front room, door architrave to rear room

Front room, door architrave to rear room

OH 43a, visible light, 200x

Front room, door leaf to rear room

Front room, door leaf to rear room

OH 34, visible light, 200x

In the third generation, all of the trim in the room was painted white, with what appears to be the same zinc-based paint that was designated generation four in the passage. In this period, the leaf to the rear room was faux-wood grained to imitate a reddish wood such as mahogany, although this faux-mahogany finish was designated generation three on the passage door leaves. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear. The leaf to the passage was either painted less frequently, or is missing some of the early paint evidence found on the door leaf to the rear room. It is important to note that none of the samples from the leaf to the passage contained the mahogany finish.

In generation 4, the trim was again painted zinc white and the leaves were faux-wood grained to imitate a lighter wood such as oak. This scheme was also seen in the front passage, albeit as generation four. In generations 5 and 6, the trim was re-painted with the zinc white paint but the faux finish on the doors was left exposed.

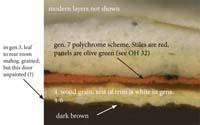

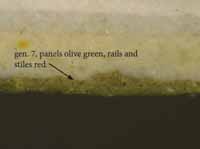

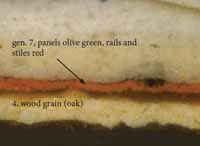

In generation 7, the trim was painted in a polychrome scheme, with olive-green fascias and orange-red backbands. This scheme was seen throughout the house and most likely dates to the late 19th-century at the earliest, based on the numerous zinc-based schemes that precede it. This scheme was designated generation five in the passage.

The sample from the mantel (OH 41) did not contain any historic paints. The cross-section suggests there are remnants of what appear to be a lead-based paint embedded deep in the wood cells, as well as a fragment of early plant resin varnish and a thin black paint, but this evidence is too fragmentary to make more definitive conclusions.

Door leaves:

OH 32a, visible light, 200x (door leaf to passage)

OH 32a, visible light, 200x (door leaf to passage)

OH 34, visible light, 200x (door leaf to rear room)

OH 34, visible light, 200x (door leaf to rear room)

The door leaves in this room were of special interest to the study. Two samples were taken from the door leaf to the passage (OH 32, OH 33), and one sample was taken from the door leaf to the rear-right (southwest) room (OH 34). The finish history was somewhat confusing, as the earliest finishes are a series of very deteriorated dark brown paints, so it was very difficult to interpret the evidence.

42Only one dark brown paint was seen on the leaf to the passage, while two were (possibly) seen on the leaf to the rear room. This could suggest that the passage leaf is later, but it is complicated by the fact that the passage side of this leaf does align with the other passage leaf, so this leaf appears to be original, unless both passage doors are early additions.

Interestingly, the leaf to the rear room was wood grained to imitate mahogany in the third generation, but this finish was not found on the passage leaf. This might have communicated the higher status of the rear room over the passage, as was suggested by the architraves on these doors and the level of finish. Further sampling or in-situ investigation is recommended to be certain this mahogany finish is absent from the passage leaf, although this finish post-dates the colonial period.

First floor, front right (northwest) room, sample locations

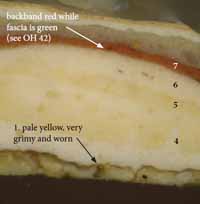

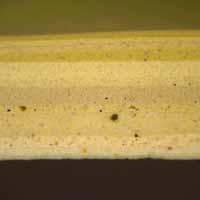

44Chair rail

Approximately thirty generations of paint were found on the chair rail (see next page for rest of stratigraphy). The first generation is a light yellow paint that contains coarsely ground pigment particles. Although it is in relatively good condition in this sample, in other samples this paint is severely cracked, soiled, and worn, suggesting it was exposed for a very long period of time before being repainted (see OH 30, pp.47-48).

Generations two and three were dark brown paints found only in the samples taken from the door architraves (see OH 46, p.49), suggesting that the rest of the trim was unpainted in these periods.

Generation four is the white paint that contains 'twinkling' autofluorescent particles of zinc white (ZnO), which would post-date this generation to c.1845. This paint was found throughout the first floor.

46Approximately thirty finish generations were found on the chair rail. The photomicrograph above continues from the previous page.

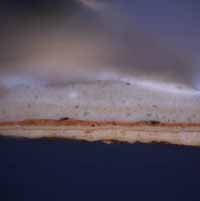

Window architrave, backband (west wall)

The first generation light yellow paint on the west wall window architrave backband is the same as that found on the chair rail and door architraves in this room. This paint is severely worn and grimy.

The second and third generation dark brown paint on the door architraves is not seen here, so presumably the window architraves were left unpainted in this period.

Generation four is the zinc-based paint seen throughout the house.

The rest of the stratigraphy is shown on the next page.

48Generations 1-7 in sample OH 30, taken from the window architrave backband, align with the paint history of the door architrave backband (with the exception of generations 2 and 3, see OH 46, p. 49). The first generation is a very worn and deteriorated light yellow paint. In generations 2 and 3, the door architraves in this room were painted dark brown, but the window architraves were not painted. Generations 4-6 are zinc-based paints that date to the mid-19th century or later.

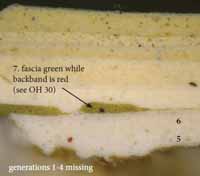

In generation 7, the window architraves were painted similarly to the door architraves. The inner fascias were olive green (see below), and the backbands were red (see above). This is most likely a late-19th-century scheme, based on the numerous zinc-based paints that precede it.

Door architrave to passage (left jamb, backband)

Approximately thirty paint generations were identified on the door architrave backband to the passage. The first generation is a very cracked and deteriorated pale yellow paint, which appears to have been contemporary with the verdigris in the passage. For further discussion, see next page (door architrave inner fascia).

Door architrave to passage (inner fascia)

The first generation light yellow paint is seen at the bottom of sample OH 43, taken from the door architrave to the passage. This light yellow paint is extensively cracked, worn, and soiled, suggesting it was exposed for a very long period of time. It seems likely that this color is contemporary with the verdigris greens in the passage, which were also extensively deteriorated before being repainted by the zinc white paint.

Generations two and three are dark brown paints, which were found in the other door architrave sample (OH 46, previous page), although it does not appear to have been used on any other trim in this room.

Generations 4-6 are white paints made with zinc white pigment, which would date to the mid- 19th century or later. Comparison of this sample with that of the door leaves suggests that these white paints are contemporary with faux-wood graining on the door leaves.

51Comparison of the above sample (taken from the inner fascia of the door architrave), and the sample taken from the door architrave backband (previous page), suggests that in generation 7, the door architrave was picked out in a polychrome scheme, with an olive green fascia and an orange-red backband. This scheme could date to the late 19th century, suggested by the series of zinc-based paints that precede it.

Mantel

In-situ investigation of the mantel did not find any 18th-century paints, and the cross-section evidence confirmed this observation. However, the surface of the wood is quite rough which could suggest that the mantel was scraped down or stripped at some point in its history. There were some remnants of a lead-based oil paint deep in the wood cells (based on the opaque, cream colored material in visible light and the peach-colored autofluorescence in UV). This could be an 18th-century paint, but this evidence is too fragmentary to make further conclusions.

This is followed by a plant resin varnish, and a thin layer of black paint. Again, this evidence is so fragmentary that a relative date could not be assigned. The remainder of the stratigraphy is made up of industrially-prepared paints that were applied by CWF.

Door leaf to passage (left stile)

The first generation applied to the door leaf is a dark brown paint. This paint is very finely ground and appears to align with the third generation finely ground dark brown paint used in the front passage (see comparison to sample OH 44, next page). If these are the same paints, it would suggest that this leaf is an early addition, or that this side of the leaf was originally unpainted for the first two decorative generations. However, there is no dirt on the surface of the wood to suggest that this is the case. It is also very possible that the earliest finishes are lost from this side of the leaf, although a second sample from this same leaf also found only one dark brown paint (OH 32).

To further complicate the interpretation, the passage-side of this same leaf has comparatively more early paint layers, including what appear to be at least two generations of dark brown paints, followed by a third generation red-orange faux-wood graining, and a fourth generation light oak graining, which appears to align with generation 4 above. This was also found on the rest of the first floor leaves and suggests this leaf is original. This would conflict with the theory that this leaf is an early addition. It is unclear why the earliest dark brown paints are missing from this door leaf.

Front room, leaf to passage (stile)

Front room, leaf to passage (stile)

OH 33a, visible light, 200x

Passage, door architrave to front room

Passage, door architrave to front room

OH 44b, visible light, 200x

As shown above, the earliest dark brown paint on the door leaf to the passage (OH 32, OH 33), appears to be the same finely ground dark brown paint used in the passage in the third generation (OH 44). [Please note this is not strongly apparent in the printed image due to the darkness of the earliest paints in sample OH 44b].

55 Front room, leaf to passage (panel)

Front room, leaf to passage (panel)

OH 32b, visible light, 200x

Front room, leaf to passage (stile)

Front room, leaf to passage (stile)

OH 33b, visible light, 200x

The samples above are shown to illustrate that in the seventh generation, the door leaf panels were painted olive green while the stiles (and most likely, rails), were painted orange-red. This scheme was found throughout the house on the first floor, and appears to date to the late 19th-century. Its identification assisted with the interpretation of other paints throughout the house.

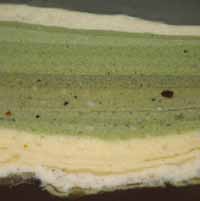

Door leaf to rear room (bottom left panel)

The early paint history of the door leaf leading to the rear-right (southwest) room aligns with that of the door leafs in the passage (OH 31 and OH 39, currently facing the room-side). This consists of first period dark brown paints, which are very disrupted, but there does appear to be more than one generation present, suggested by the differing autofluorescences of the paints.

This is followed by a faux-wood graining finish that appears to imitate mahogany or some other red-colored wood. Interestingly, this reddish faux-wood grain was only used on the leaf to the rear room (double architrave), and it was not used on the leaf to the passage (single architrave). See next page for comparison.

57 Door leaf to rear room

OH 34b, visible light, 200x

Door leaf to rear room

OH 34b, visible light, 200x

Door leaf to passage

OH 33b, visible light, 200x

Door leaf to passage

OH 33b, visible light, 200x

The comparison of the two samples above shows that the door leaf to the passage (OH 33) has fewer paint layers than the leaf to the rear room (OH 34).

The rear room leaf (left) begins with (possibly) two generations of very disrupted dark brown paints, while only one dark brown paint was found on the leaf to the passage (right).

Furthermore, the leaf to the rear room received a faux-mahogany finish in the third generation (left), which was not found on the leaf to the passage (right).

In the fourth generation, both leafs were grained in imitation of a light wood, most likely oak. During this time the trim in the room was painted white. This scheme was also found in the passage in the fourth generation.

Binding Media Analysis

Sample OH 30 was stained with biological fluorochromes to characterize the binding media. The results are summarized in the table below.

| Generation | Description | DCF rxn | FITC rxn | TTC rxn | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | white paint | + | - | + | oil bound with some carbohydrate component, possibly gum |

| 8 | light gray paint | - | - | - | appears oil bound |

| 7 | orange-red paint | + | - | - | oil bound |

| 6 | white paint | + | - | - | oil bound |

| 5 | white paint | - | - | - | appears oil bound |

| 4 | white paint | + | - | - | oil bound |

| 3 | missing | x | x | x | x |

| 2 | missing | x | x | x | x |

| 1 | light yellow paint | weak + | - | - | oil bound |

DCF for lipids (oils)

OH 30, B-2A filter, 200x. Before DCF stain.

OH 30, B-2A filter, 200x. Before DCF stain.

OH 30, B-2A filter, 200x. DCF reaction.

OH 30, B-2A filter, 200x. DCF reaction.

The early paints in sample OH 30 were stained with DCF to tag lipids (oils) in the sample. Spotty positive reactions were observed in generation 1. A strong positive reaction was observed in generation 4 and in generations 6, 7, and 9. These reactions would suggest these paints are oil bound.

First Floor, Rear-Right (Southwest) Room:

Eight samples were collected from the first-floor, rear-right (southwest) room woodwork

| OH 35 | North wall, chair rail, 4" away from east wall |

| OH 39 | East wall, door leaf to current kitchenette/passage, bottom left panel, lower R beveled edge |

| OH 40 | North wall, door leaf to front room, top rail, far right edge where meets right stile |

| OH 47 | East wall, door architrave to current kitchenette/passage, backband, left jamb, 60" from floor |

| OH 48 | North wall, door leaf to front room, bottom L-hinge, top edge |

| OH 49 | North wall, door leaf to front room, center stile, 23" from floor |

| OH 50 | North wall, door architrave to front room, cyma of backband, left jamb, 24" from floor |

| OH 51 | West wall, window architrave, left jamb, backband |

Description/Observations:

This room has a narrower chair board and no bolection, indicating lower status than the front room and passage. The door architraves leading to the rear passage and front room are single architraves, as is the original window architrave on the west window.

As described in the previous section of this report, the door leaf to the front room is original and has a superior finish.

The original door leaf to the rear passage appears to have been reversed, as it presently has its superior finish on the room-side.

The exterior (south) doorway, south window, cornice, and mantel in this room are modern.

Summary of Analytical Results:

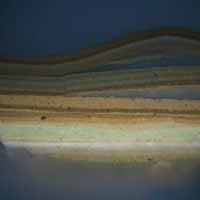

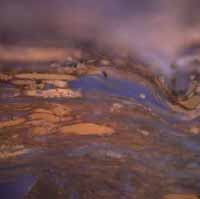

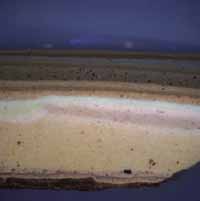

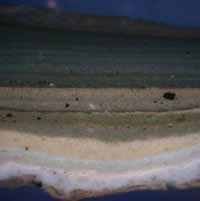

Approximately twenty-two paint generations were found in the rear-right (southwest) room. Early paint sequences were found in samples taken from the chair rail (OH 35), the door architraves (OH 50, OH 47), and the window architrave (OH 51). The findings suggest that this room might have been re-painted more often than other rooms/elements in the house. For instance, the third generation deep-green verdigris finish on the chair rail appears to align with the second generation deep green verdigris in the passage (see below).

Rear room, chair rail

Rear room, chair rail

OH 35a, visible light, 200x

Front passage, chair rail

Front passage, chair rail

OH 21a, visible light, 200x

In this room, generation 1 is a coarsely ground gray paint on the trim and dark brown on the door leaves. Comparison of the two samples on the previous page suggests that the first generation gray paint in this room could be the same as the gray base coat seen in the stair passage. Their pigment dispersions (PLM) were very similar, as were their appearances in cross-section and their color matches, which suggests that these are actually the same paints. The dark brown on the door leaves appears to be the same dark brown paint used in the passage and second-floor woodwork in this sample period.

Generation 2 is a light yellow paint on the trim that appears to be the same color as the first generation yellow paint in the adjacent front room. Uncast portions of both of these paints from both rooms were compared at low magnification (30x) and they visually appear to be the same. In fact, their color matches (visual only, too disrupted for colorimetry reading) were also the same, suggesting these were either the same paints, or at least the same color executed in different paints. During this same period, the door leaves were coated with a dark brown varnish.

Generation 3 is another coarsely ground gray base coat (3a) followed by a deep green verdigris green glaze (3b). This verdigris generation is very worn and uneven, similar to the third generation verdigris in the stair passage.

In the fourth generation, the door architraves were re-painted dark brown (see sample OH 47). The other trim was not painted in this period, and would have remained deep green. The same scheme was seen in the passage, as well.

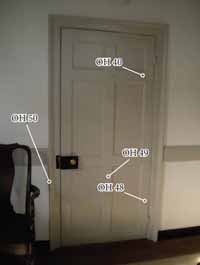

First floor, Rear-Right (Southwest) Room, Sample Locations

door to present kitchenette (passage)

door to present kitchenette (passage)

door to front right (northwest) front room

door to front right (northwest) front room

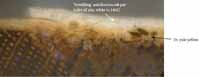

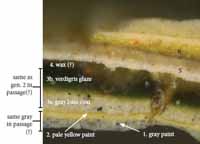

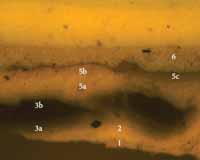

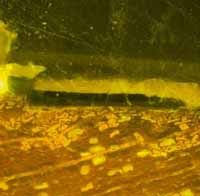

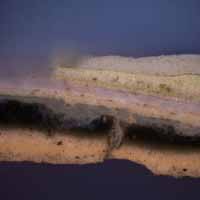

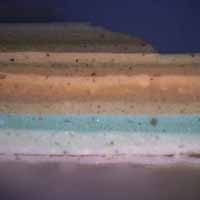

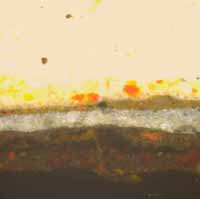

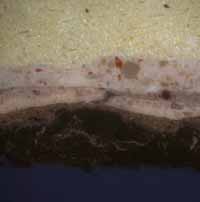

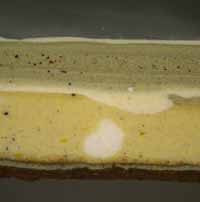

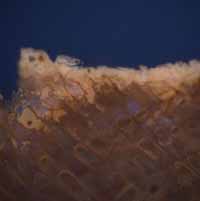

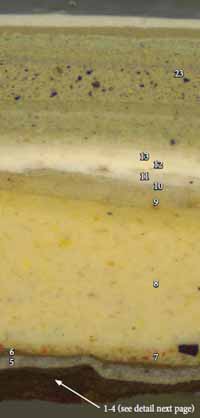

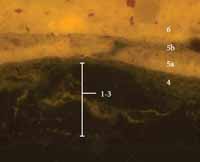

Chair rail

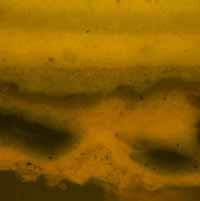

Approximately twenty-two generations of paint were found on the chair rail. The first generation is a coarsely ground gray paint that appears to be the same as the first generation used in the stair passage. Generation 2 is a light yellow paint that appears to be the same as the yellow paint used in the front room in generation one. While these yellow paints appear slightly different in cross-section (see next page), it is possible that the rear room was painted to match the already yellow front room in the second generation, although this is uncertain.

64The third generation is a gray base coat (3a) followed by a deep green glaze/paint (3b) made with verdigris pigment. This could align with the second generation verdigris in the stair passage, because both are heavily cracked and deteriorated.

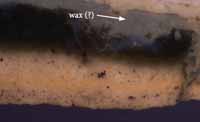

In sample OH 35 (previous page), there appears to be a waxy coating applied to the verdigris when it was already degraded, as the wax flows into pre-existing cracks. This wax coating is designated generation 4.

Comparison of early pale yellow paints in first-floor front room and rear room

Generation 5 is a pinkish-beige paint and varnish that appears to align with the third generation paint on the stair in the passage. Generation 6 is the olive green paint used throughout the house. This olive green paint is believed to belong to a late 19th-century scheme.

Door architrave to front room

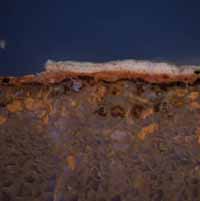

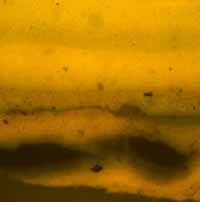

Like the chair rails in the rear room, the door architraves begin with a gray paint (1), followed by a light yellow paint (2). The third generation is composed of a gray base coat (3a) and a deep green verdigris finish (3b).

In the fourth generation, the door architraves were painted dark brown (4). [Please note: it is difficult to discern this dark brown paint from the third generation verdigris in the above photomicrograph]. This treatment of the door architraves being picked out in dark brown was also seen in passage and the adjacent living room during this same period. The other trim was not re-painted at this time.

Door architrave to present kitchenette/passage

Sample OH 47, collected from the door architrave to the passage, contains a more complete stratigraphy, although the early paints are very disrupted.

Approximately twenty-two paint generations are present. The first generation is a gray paint, followed by the second generation pale yellow paint. The third generation is a gray base coat and verdigris glaze that appears to align with the second generation verdigris finish in the passage.

Window architrave (west wall)

Approximately twenty-two generations of paint were identified on the window architrave. The earliest finishes were very disrupted, but remnants of the first generation gray paint, second generation light yellow paint, and third generation verdigris can be seen.

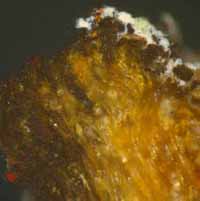

Door leaf to front room, hinge

OH 48a, visible light, 100x (enlarged)

OH 48a, visible light, 100x (enlarged)

OH 48a, UV light, 100x (enlarged)

OH 48a, UV light, 100x (enlarged)

Approximately 24 generations were identified on the hinge of the door leaf to the front room.

The earliest paints are discussed on the next page.

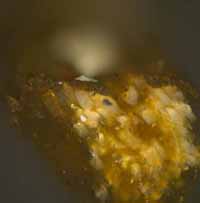

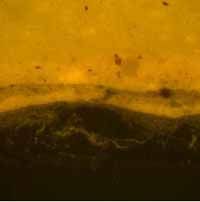

69Generation 1 is a coarsely ground dark brown paint which contains large red pigment particles. This paint is very cracked and disrupted. Generation 2 is a dark brown coating. The dark autofluorescence suggests it could be an oil-based varnish. Generation 3 is fragmentary but is another dark brown paint, with a slightly more yellow hue. This paint is seen to flow between cracks in generations 1 and 2. Generation 4 is another coarsely ground red-brown paint which has a brighter autofluorescence in comparison to generations 1-3, suggesting some type of varnish additive.

Door leaf to front room (top rail)

Approximately twenty-two paint generations were identified on the door leaf to the front room. The earliest generation is a thin, very deteriorated dark brown paint with no autofluorescence, which seems to align with generation 2 on the hinge of the same door (previous page). The next generation has a comparatively brighter autofluorescence (suggesting a resinous component), 71 which flows into pre-existing cracks in the earlier generations. This seems to align with generation 4 on the hinge of the same door. Although fragmentary, these finishes are similar to those seen on the leaves and stair in the first-floor passage (OH 31, OH 26, OH 27, OH 38) , as well as the leaves in the front room (OH 34).

Generation 5 is a zinc-based light gray paint, and generation 6 is the olive-green paint that is seen on all woodwork in the house and most likely dates to a late 19th-century scheme.

Door leaf to present kitchenette/passage (bottom left panel)

As discussed previously, the door leaf to the passage has been reversed. The paint history shown above aligns with that in the kitchenette/passage, rather than the bedroom which it faces. This was confirmed by examining the paint history of the other side of this same leaf, which aligns with the rear room.

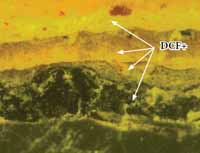

Binding Media Analysis

Sample OH 50 (first floor, rear room, door architrave to front room), was stained with biological fluorochromes to characterize the binding media. The results are summarized in the table below.

OH 50: First floor, bedroom, door architrave to living room

| Generation | Description | DCF rxn | FITC rxn | TTC rxn | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | dull red paint | + | + | + | oil bound with carbohydrate and protein components and/or false positives for modern materials |

| 5b | gray paint | + | - | + | oil bound with carbohydrate component, possibly a gum additive |

| 5a | gray primer | + | - | + | oil bound with carbohydrate component, possibly a gum additive |

| 4 | dark brown | - | - | - | oil bound (no reaction, but visual ID) |

| 3 | gray base coat (3a) and verdigris-green (3b) | - | - | - | oil bound (no reaction but visual ID) |

| 2 | pale yellow paint | - | - | - | oil bound (no reaction but visual ID) |

| 1 | gray paint | - | - | - | oil bound (no reaction but visual ID) |

DCF stain for lipids (oils)

OH 50, B-2A filter, 200x. Before DCF stain.

OH 50, B-2A filter, 200x. Before DCF stain.

OH 50, B-2A filter, 200x. DCF reaction.

OH 50, B-2A filter, 200x. DCF reaction.

Sample OH 50 was stained with DCF to tag lipids (oils) in the sample. A weak reaction was observed along the underside of the sample, and in generations 5 and 6.

Binding Media Analysis

Sample OH 48 (first floor, rear room, door leaf to front room), was stained with biological fluorochromes to characterize the binding media. The results are summarized in the table below.

| Generation | Description | DCF rxn | FITC rxn | TTC rxn | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | dull red paint | + | - | + | oil bound with carbohydrate component, possibly a gum additive |

| 5b | gray paint | + | - | + | oil bound with carbohydrate component, possibly a gum additive |

| 5a | light primer | + | - | + | oil bound with carbohydrate component, possibly a gum additive |

| 4 | red-brown paint | + | - | + | oil bound with carbohydrate component, possibly a gum additive |

| 3 | red-brown paint | + | - | - | oil bound |

| 2 | dark varnish | + | - | - | oil bound |

| 1 | dark brown paint | + | - | - | oil bound |

DCF stain for lipids (oils)

OH 48, B-2A filter, 200x. Before DCF stain.

OH 48, B-2A filter, 200x. Before DCF stain.

OH 48, B-2A filter, 200x. DCF reaction.

OH 48, B-2A filter, 200x. DCF reaction.

The early paints in sample OH 48 were stained with DCF to tag lipids (oils). Strong positive reactions were observed in all layers, suggesting they are oil bound.

FITC stain for proteins

OH 48, B-2A filter, 200x. Before FITC stain.

OH 48, B-2A filter, 200x. Before FITC stain.

OH 48, B-2A filter, 200x. FITC reaction.

OH 48, B-2A filter, 200x. FITC reaction.

The early paints in sample OH 48 were stained with FITC to tag proteins. No reactions were observed. (The lightening of generations 1-3 is not a true reaction).

TTC stain for carbohydrates

OH 48, UV light, 200x. Before TTC stain.

OH 48, UV light, 200x. Before TTC stain.

OH 48, UV light, 200x. TTC reaction.

OH 48, UV light, 200x. TTC reaction.

The early paints in sample OH 48 were stained for carbohydrates. A strong positive reaction was observed in generation 7. Weak reactions were observed in generations 4-6. The dark color of generations 1-3 made it impossible to gauge their reactions.

Pigment Identification Results

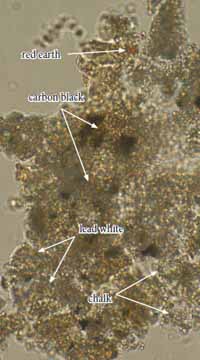

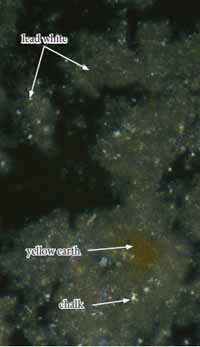

Generation one (1) gray paint (base coat for verdigris in passage)

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 gray paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 gray paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 gray paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 gray paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

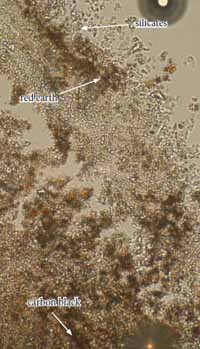

The first generation gray paint contains primarily lead white pigment (2PbCO3‧Pb(OH)2)), visible as small, rounded particles with high relief that are colorless in transmitted plane polarized light and have a bright birefringence in cross polarized light. Chalk (CaCO3) particles were also observed as larger, colorless, plate-like particles with sharp edges that have an undulose (sweeping) birefringence.

Particles of carbon black pigment (C), are also visible as larger, flat particles of varying size that are black and opaque in transmitted plane polarized light and isotropic (dark) in cross polarized light.

A very small amount of red earth pigment (Fe2O3) was found, visible as small, rounded grains with a deep red color in transmitted light that are isotropic in cross polarized light.

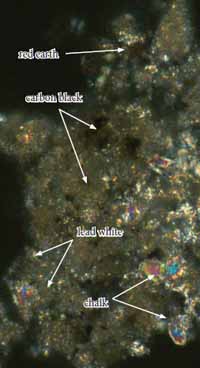

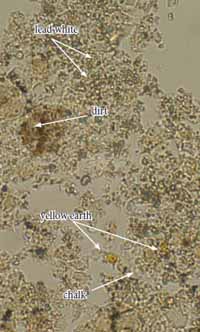

Rear right (southwest) room, Generation one (1) gray paint (OH 35, chair rail)

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 gray paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 gray paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 gray paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 gray paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

The dispersion of the first generation gray paint in the rear right (southwest) room is very similar to that from the first generation gray paint in the front passage (see previous page for comparison), strongly suggesting that these are the same paints. Here, the sample contains primarily lead white pigment (2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2)), visible as small, rounded particles with high relief that are colorless in transmitted plane polarized light and have a bright birefringence in cross polarized light. Chalk (CaCO3) particles were also observed as larger, colorless, plate-like particles with sharp edges that have an undulose (sweeping) birefringence.

Particles of carbon black pigment (C), are also visible as larger, flat particles of varying size that are black and opaque in transmitted plane polarized light and isotropic (dark) in cross polarized light. The quantity, size, shape, and dispersion of the carbon black pigments are strikingly similar to the gray paint in the front passage.

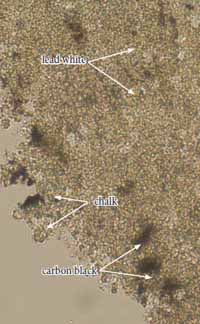

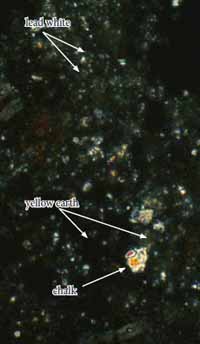

Rear right (southwest) room, Generation one (3) gray paint (OH 35, chair rail)

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 3 gray paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 3 gray paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 3 gray paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 3 gray paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

The dispersion of the third generation gray paint in the rear room is very similar to that from the first generation gray paint in the front passage and the first generation gray paint in the rear room (see previous pages for comparison)

The sample contains primarily lead white pigment (2PbCO3‧Pb(OH)2)), visible as small, rounded particles with high relief that are colorless in transmitted plane polarized light and have a bright birefringence in cross polarized light. Chalk (CaCO3) particles were also observed as larger, colorless, plate-like particles with sharp edges that have an undulose (sweeping) birefringence.

Particles of carbon black pigment (C), are also visible as larger, flat particles of varying size that are black and opaque in transmitted plane polarized light and isotropic (dark) in cross polarized light.

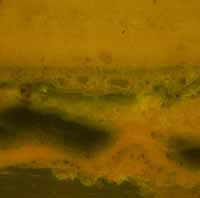

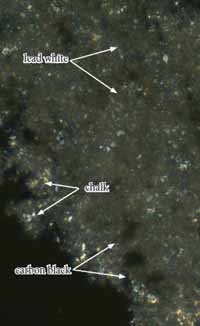

Rear right (southwest) room, Generation two (2) yellow paint (OH 35, chair rail)

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 2 yellow paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 2 yellow paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 2 yellow paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 2 yellow paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

The dispersion of the second generation yellow paint in the rear right (southwest) room contains primarily lead white pigment (2PbCO3‧Pb(OH)2)), visible as small, rounded particles with high relief that are colorless to greenish in transmitted plane polarized light and have a bright birefringence in cross polarized light. Larger, plate-like particles of chalk (CaCO3), were also observed.

Particles of yellow earth (Fe2O3 ‧ nH2O) are also visible as large agglomerations of golden-yellow colored particles of varying size that are isotropic (dark) in cross polarized light.

Comparison of this yellow paint with the first generation yellow paint in the adjacent front right (northwest) room suggests these are the same paints, although their dispersions appear slightly different with PLM, which could be due to the more severe disruption of the yellow paint in the front right room (see next page).

Front right (northwest) room, Generation one (1) yellow paint (OH 43, door architrave)

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 yellow paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 yellow paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 yellow paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 yellow paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

The dispersion of the first generation yellow paint in the front right (northwest) room contains primarily lead white pigment (2PbCO3‧Pb(OH)2)), visible as small, rounded particles with high relief that are colorless to greenish in transmitted plane polarized light and have a bright birefringence in cross polarized light. Larger, plate-like particles of chalk (CaCO3), were also observed.

Yellow earth (Fe2O3 ‧ nH2O) are also visible as agglomerations of golden-yellow colored particles of varying size that are isotropic (dark) in cross polarized light.

Some dark, isotropic black and brown particles were also observed, which are most likely from the dirt and grime embedded in this layer, and are not deliberately added pigments.

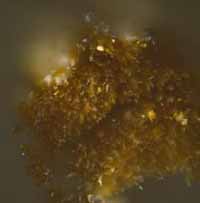

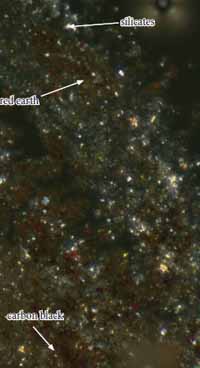

Passage, Generation 1c verdigris (?)-green paint

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1c green paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1c green paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1c green paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1c green paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

The dispersion of the first generation green paint in the passage did not contain any green-colored pigments, although very large particles of what appeared to be verdigris-green pigments were seen in the cross-sections and in the uncast portions.

This sample does contain mostly lead white pigment (2PbCO3‧Pb(OH)2)), visible as small, rounded particles with high relief that are colorless to greenish in transmitted plane polarized light and have a bright birefringence in cross polarized light.

Rear right (southwest) room, Generation three (3) green glaze (OH 35, chair rail), same as generation two (2) green glaze in stair passage

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 3 green paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 3 green paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 3 green paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 3 green paint. Cross polarized transmitted light, 1000x

The dispersion of the third generation green paint in the rear right (southwest) room did not contain any green-colored pigments, but amorphous areas of green glaze were observed to have a conchoidal fracture, indicative of a copper-resinate glaze made with verdigris pigment in heated resin. This type of glaze is isotropic (dark) in crossed polars.

There was also a good deal of lead white pigment (2PbCO3°Pb(OH)2)), visible as small, rounded particles with high relief that are colorless to greenish in transmitted plane polarized light and have a bright birefringence in cross polarized light. It is unclear if this was a component of the glaze or a contaminant from an adjacent paint.

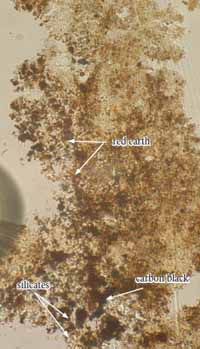

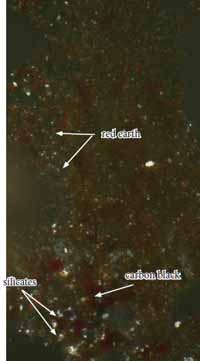

Front Passage, Generation one (1) dark brown paint on door leaves and stair (OH 27, newel)

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 brown paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 brown paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 brown paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 brown paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

The dispersion of the first generation brown paint in the front passage contains primarily isotropic red earth pigments (Fe2O3) and carbon black (C).

Some scattered colorless and birefingent particles were also observed, most likely silicate (SiO2) inclusions that accompany earth pigments.

Front right (northwest) room, Generation one (1) dark brown paint on door leaves (OH 33)

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 brown paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 brown paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 brown paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from generation 1 brown paint. Plane polarized transmitted light, 1000x

The dispersion of the first generation brown paint in the front right (northwest) room contains primarily isotropic red earth pigments (Fe2O3) and carbon black (C). This appears to be the dark brown same paint used in the front passage (see previous page for comparison).

Some scattered colorless and birefingent particles were also observed, most likely silicate (SiO2) inclusions that accompany earth pigments.

Color Matching Results

Generation 1a gray paint in front passage and rear right room

OH 24a, visible light, 200x (Front Passage)

OH 24a, visible light, 200x (Front Passage)

OH 35a, visible light, 200x (Rear Right Room)

OH 35a, visible light, 200x (Rear Right Room)

Consistent values for the first generation dark gray paint in the front passage and rear right room could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter colorimeter/microscope. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest commercial color match was determined to be Benjamin Moore 2126-30 "Anchor Gray".

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* | a* | b* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41.19 | -0.74 | -3.96 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 2.0PB | 4.0 | 0.9 |

Generation 1b green paint in front passage

OH 24a, visible light, 200x (Front Passage)

OH 24a, visible light, 200x (Front Passage)

The first generation green paint in the front passage was made with verdigris, which oxidizes and becomes brown and dark with time. Although the present color of this paint does not accurately reflect its 18th-century appearance, a match was obtained for documentation purposes. Measurements could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter colorimeter/microscope because a clean, intact area could not be isolated for measurement. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest commercial color match was determined to be Benjamin Moore HC-135 "Lafayette Green".

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* | a* | b* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 37.48 | -11.24 | +2.03 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 8.3G | 3.6 | 2.1 |

Generation 1 dark brown paint in entire house (some trim and door leaves on first floor, baseboards and door leaves on second floor)

OH 26a, visible light, 200x (Front Passage, stair)

OH 26a, visible light, 200x (Front Passage, stair)

The first generation dark brown paint in the house was measured with a Minolta Chroma Meter colorimeter/microscope to obtain color values in CIE L*a*b* and Munsell colorspace.

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 28.97 | +1.63 | +3.63 | |

| Munsell Values | hue | value | chroma |

| 7.7YR | 2.8 | 0.6 |

The closest commercial color match was determined to be Martin Senour/Colonial Williamsburg #115 "Tucker House Chocolate". The color difference (rE) between this swatch and the sample was calculated as 3.21 (see Appendix B for details). The average human eye cannot detect rE values less than 3 (Wolbers 2008), so the difference between the original paint and the commercial match is just perceptible to the human eye, and is therefore an excellent visual match.

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* | a* | b* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 59.54 | -8.87 | -6.22 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 2.4B | 5.9 | 2.4 |

Generation 1 yellow paint on trim in front right (northwest) room and generation 2 yellow paint in rear right (southwest) room