Cross-Section Microscopy Analysis of Interior Paints: Palmer House (Block 9, Building 24), Williamsburg, Virginia

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1750

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2014

CROSS-SECTION MICROSCOPY ANALYSIS REPORT

PALMER HOUSE

Block 9, Building 24, Lot 27

Original Interior Woodwork

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION

WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA

Palmer House Interior: Cross-Section Microscopy Analysis Report — June 2011

Palmer House, Block 9, Building 24, Lot 27

Photo CWF archives

Palmer House, Block 9, Building 24, Lot 27

Photo CWF archives

| Structure: | Palmer House, block 9, building 24, lot 27 |

|---|---|

| Requested by: | Edward Chappell, Roberts Director of Architectural and Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation |

| Analyzed by: | Kirsten Travers, Graduate Fellow, Winterthur / University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation |

| Consulted: | Susan L. Buck, P.hD., Conservator and Paint Analyst, Williamsburg, Virginia |

| Date submitted: | June 2011 |

Purpose:

The purpose of this investigation is to document the paint history and identify the earliest finishes on original surviving interior woodwork at the Palmer House, particularly the first generation.

Description and history:

The Palmer House has a prominent location at the east end of Duke of Gloucester Street adjacent to Capitol Square. The present building is believed to have been constructed c.1755, by John Palmer, a lawyer and bursar of the College of William and Mary, to replace an earlier dwelling house that had been destroyed by a disastrous fire the previous year (Stephenson 1960, 2). This brick house has a two-story, double-pile, side passage plan with a gabled roof, and a chimney to the west. It measures roughly 40' x 36' around the perimeter. The brick is laid in Flemish bond, and cellar level is relatively high and ends in a beveled brick water table course, which is echoed by a three-brick-wide belt course that runs the perimeter of the exterior along the top of the first-floor windows and doors. The wood modillion cornice is mostly original, as is the stone stairway leading up to the front door. This door enters into a spacious hall with a generous staircase to the east. Two first-floor rooms are located on the western side of the house: a large room at the front, and a slightly smaller room at the rear, both with a corner fireplace. The second floor may have originally had a similar arrangement, with an open passage that led to two chambers to the west and a third chamber at the north end of the hall (Douglas 1956, 3).

The design Palmer chose for his new dwelling suggests a taste for London townhouses contemporary to the period. Whiffen writes that "its austere fenestration, and its sober, bulky mass, [are] all linked to English design prototypes," with the exception of its foundation walls, which were fitted with wood grilles to provide light and ventilation as opposed to the sunken full-sized windows that rose above grade in its London counterparts (Whiffen 1986, 198). In fact, Whiffen goes on to say "One is tempted to wonder if its original builder envisioned the whole of this important section along Duke of Gloucester street as one day being lined with formal rows, or terraces, of such residences." (Ibid). Present architectural historians interpreted the form as more a response to local and regional needs than a direct reference to English rowhouses (Chappell to Travers 2011).

3Palmer died in 1760 and his family rented the house to tenants for the next twenty years. During this time, Benjamin Bucktrout, a cabinetmaker, was one of the lessees. In February 1769, he advertised for someone to take up his lease on the property. His advertisement in the Virginia Gazette describes the house as "a large and commodious brick house, opposite to the coffee-house and nigh the Capitol. It has every necessary convenience…and has been long used by many Gentlemen in Assembly and Court times" (Stephenson 1960, 15) .

John Minson Galt, an apothecary, appears to have taken up Bucktrout's lease on the Palmer House. On September 21, 1769, Galt advertised in the Gazette a range of goods recently imported, and that "the subscriber [Galt] intends opening shop at the brick house opposite the coffeehouse…" (Stephenson 1956, 16). In addition to the drugs and medicines Galt lists in his advertisement, finishing materials such as verdigris, cochineal, as well as gold and silver leaf, were included (Ibid).

Galt occupied the house until approximately 1770. In 1780, it was sold by the heirs of the Palmer estate, and it passed through the hands of numerous owners including John Drewidz and Charles Hunt, who operated a snuff manufactory on the property from 1784 to 1810 (Stephenson 1960, 1). Records show that shortly after acquiring the house Drewidz hired Humphrey Harwood to make extensive changes and repairs. Harwood's 1784 account book notes for the Drewidz property "whitewashing 6 rooms and 2 passages with stairway, plastering, repairing cellar wall and steps…" (Stephenson 1960, 21) . Following Drewidz and Hunt, the house was owned by Carter Burwell until 1831 (Stephenson 1960, illustration 7).

In 1834 the property was purchased by William Vest, a prosperous Williamsburg merchant with a store on Duke of Gloucester street. Around 1838, Vest made extensive changes to the house, including building a brick addition measuring 24' x 36' to the to the east of the house, almost doubling it in size, and adding a large porch and other wood additions to the rear of the building (Stephenson 1960, illustration 7). Dormers were also added at this time.

When the Civil War came to Williamsburg, Vest fled to Richmond, and for three years the house was almost continuously occupied by both Confederate or Union military leaders for use as headquarters. First, it was occupied by General Johnson of the Confederate Army, and later by General McClellan during the Peninsula Campaign. In a letter dated 1862, McClellan described Williamsburg and the house: "This is a beautiful town; several very old houses and churches, pretty gardens. I have taken possession of a very fine old house which Joe Johnston occupied as headquarters. It has a lovely flower garden, and conservatory" (Stephenson 1960, 31). After the war, Vest returned to the house where he continued to live until his death in 1893 (Ibid).

The house passed through several owners until it was purchased in 1927 by W. A. R. Goodwin on behalf of the Williamsburg Restoration. It was extensively repaired from 1932-1933 during which time it was outfitted with modern conveniences including a bathroom, electric fixtures and a new kitchen (Douglas 1956, 2). In 1951, Colonial Williamsburg decided to restore the house to the period of the Palmer residency (1755-1760), which entailed removing the 19th-century Vest additions, and was accomplished that same year. It was opened to the public in 1952 (Ibid).

4 Palmer House, date unknown, but most likely before the extensive repairs of 1932-33.

Palmer House, date unknown, but most likely before the extensive repairs of 1932-33.

Photo CWF archives.

Palmer House, date unknown, but most likely after the repairs of 1932-33, but before the

19th-century additions were removed in 1951-52.

Palmer House, date unknown, but most likely after the repairs of 1932-33, but before the

19th-century additions were removed in 1951-52.

Photo CWF archives.

Condition:

Only selected elements of the original interior woodwork remain in the Palmer House. Much of the present woodwork is new, based on the fragments of surviving woodwork or contemporary models. However, enough remains to gain a general understanding of the level of interior finish over the years through cross-section microscopy. The stair in the entry hall is almost completely original including the baseboards, stringers, balusters, newel posts, and hand rail. Other surviving original elements include the interior cellar entrance door and trim beneath the stairs, the first-floor south (rear) exterior entrance door and trim, the door leaf to the west closet in the first-floor living room, and the door leaf to the west closet in the second-floor north bedroom. Although not mentioned in the report, on-site examination suggests that the frame of the south cellar door on the north-south partition is also original (Chappell 2011, sampling memo). The architectural report notes that an original chair board was found in the south room on the second-floor (Douglas 1956, 30), but this could not be located, either on-site or in the architectural fragments collection at CW.

Restoration-era paint specifications:

The following colors were specified for interior woodwork at the Palmer House during the 1951-1952 restoration:

| Floor/Room | Element | Color |

|---|---|---|

| First, second/all | baseboards | black |

| First floor | closet doors, front and rear doors in hall | dark green #827 |

| First floor | all other doors (except kitchen) | dark brown #773 |

| Cellar | all woodwork | flat white |

| First floor/staircase | handrail, newels, balusters | dark green #827 |

| stringers | dark brown #773 | |

| Second floor/north bedroom | all woodwork | gray green #101 |

Previous finishes research:

In 2007, paint analyst Natasha Loeblich used cross-section microscopy techniques to determine the paint history of original exterior elements of the Palmer House (Loeblich 2007). Elements studied included the front (north) and rear (south) cornice, the rear (south) doorway, and the brickwork. Nineteen samples were taken. The results found original paints on the cornice and the rear door architrave and leaf. The first five paint generations on the cornice were oil-bound lead white paints. The same paints, although relatively more disrupted, were also found on the rear door architrave. The rear door leaf appeared to have been painted more often than the trim, consisting of a first generation white primer with red-brown finish coat, and a second red-brown paint generation, followed by three bright-green generations. Successive generations include bright orange and green colors, faux-wood graining and decorative finishes. Remnants of what could be a thin red limewash were found on the original mortar joints, but the evidence was elusive and Loeblich suggested additional analyses to further study the nature of this coating.

Procedures:

Thirty-one samples were collected on two separate occasions from the interior of the Palmer House. On May 27, 2011, Kirsten Travers, accompanied by Edward Chappell, collected eighteen paint samples from various original interior elements including the main stair, the first-floor living room closet door leaf, the first-floor rear (south) entrance door leaf, the basement entrance door leaf (under the main stairs), and the closet door leaf on the second floor, north bedroom. On June 16, 2001, Travers returned to the house to collect additional samples from the cellar door frames, the cellar entrance door in the entry hall, the main stair, and the closet door leaf in the second-floor north bedroom.

On site, a monocular 30x microscope was used to examine the painted surfaces and determine the most appropriate areas for sampling. A micro-scalpel was used to remove the samples, which were labeled and stored in small individual Ziploc bags for transport. All samples were given the prefix "PH" and numbered according to the order in which they were collected.

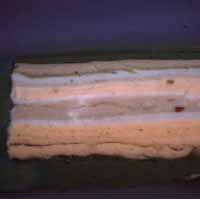

In the laboratory, the samples were examined with a stereomicroscope under low power magnification (5x to 50x), to identify those that contained the most intact paint evidence and would therefore be the best candidates for cross-section microscopy. Uncast sample portions were retained for future examination and analysis. The best candidates were cast in resin cubes and sanded and polished to expose the cross-section surface for microscopic examination.

Once cast, the cross-section samples were examined and digitally photographed in reflected visible and ultraviolet light conditions at 20x to 400x magnifications. By comparing the resulting photomicrographs, finish generations could be interpreted based on physical characteristics such as color, texture, thickness, presence of dirt layers and extent of surface deterioration. Fluorochrome staining was also carried out on selected samples to characterize the types of binding media present (oils, carbohydrates, proteins). The most informative photomicrographs and their corresponding annotations, as well as comments from the author, are contained in the body of this report. All raw photomicrographs can be found in the Appendix.

Summary of Results:

A good deal of paint evidence remains intact on original woodwork in the Palmer House, allowing a general glimpse into the earliest color schemes. The most intact paint samples contain over twenty generations of paint.

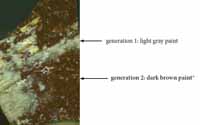

The first generation finish on almost all of the woodwork appears to be a light gray paint. In three samples (PH 28: handrail, PH 19: cellar door leaf, and PH 15: living room door leaf), the surface of this paint is worn and/or deeply cracked, indicating that it was a finish layer that was exposed for an extended period of time. In the second generation, the woodwork received a polychrome scheme; the door leaves on the first and second floors were painted dark brown and varnished, the baseboards on the stair were painted black and varnished, and the stairs and trim were painted a deep green color made with verdigris. This is similar to the color scheme in place today, suggesting that some color research (ie: scraping), might have been carried out during the restoration, although no record of this was found in the reports (beyond the brief reference noted above).

Throughout the 19th century, and possibly into the 20th, lighter colors such as whites, creams, and grays were applied to the stairs and trim, while the stair handrail and door leaves were decoratively painted to imitate more expensive woods.

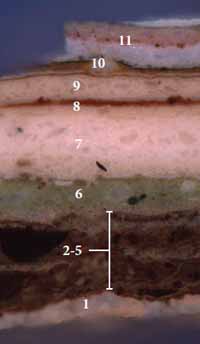

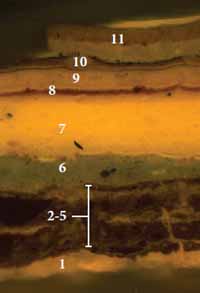

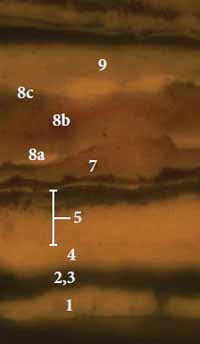

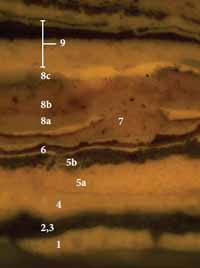

The results in this report are presented according to element, the main staircase in the entry hall being discussed first. Each section includes a general description of the element, its history and its condition, sample location photographs, and an interpretation of the paint analysis results in prose accompanied by relevant cross-section photomicrographs. Where cross-section photomicrographs are shown, paint stratigraphies have been annotated according to finish "generation." For instance, a primer, paint layer, and varnish may represent one finish generation and are all given the same number, but differentiated with lowercase letters (1a, 1b, 1c, etc.), according to the order in which they would have been applied. Some paint samples contained redundant evidence, so only the most relevant samples are used in the report. Pigment identification with polarized light microscopy, binding media analysis with fluorochrome staining, and color matching are treated in separate sections at the end of the report. All results are interpreted in the conclusion, and all sampling memoranda and raw photomicrographs can be found in the appendix at the back of this report.

Staircase

Description:

The main stair is located on the east wall, and has two landings on the ascent to the second-floor passage. It is a wide, generous staircase of the closed string type with square newel posts, a molded handrail and turned balusters with square bases and caps. It is largely original, including the stringers, balusters, risers and treads, handrails and newel posts, (Douglas 1956, 19). However, Edward Chappell noted that the north and west upper stringers appear new (Chappell 2011, sample memo).

The architectural report notes that the stairs were cleaned and waxed during the restoration (Douglas, 19). The interior paint color schedule in that same report relates that at that time the handrail, newels, and balusters were painted dark green #827, with the outer stringer dark brown #773. The risers and treads were waxed, and the baseboards were painted black. The same color scheme is in place today. During sampling, substantial accumulations of paint were visible in raking light, suggesting that the finish history was left intact.

Results:

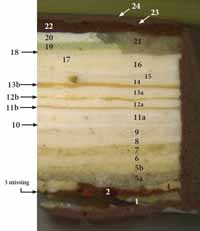

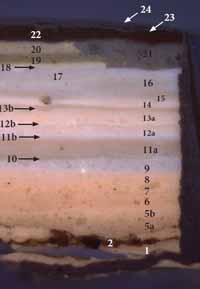

Twelve paint samples in total were collected from the staircase. Two samples were collected from the stringers (PH 1, PH 4), three samples were collected from the balusters (PH 2, PH 3, PH 6), two samples were taken from the newel posts (PH 5, PH 7), two samples were taken from the handrail (PH 9, PH 28), and three from the baseboard (PH 10, PH 26, PH 27).

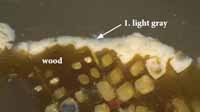

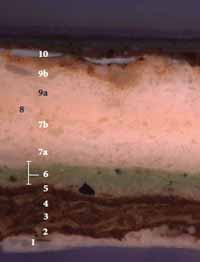

Approximately twenty-four generations of paint are extant on the staircase. In the first generation, the entire staircase was painted a light gray color. (This paint appears white in cross-section due to the intensity of incident light at high magnifications). PLM found that this paint is comprised chiefly of lead white pigment, with chalk additives (a common paint extender), carbon blacks and a very small amount of red ochre that lends this color an overall warm hue. This paint was applied to all elements, including the stringers, balusters, handrail, and baseboards. At first glance, this paint appeared to be a priming layer, but sample PH 28a (taken from the handrail), clearly illustrates that there were deep cracks in the surface of this light gray paint when the second-generation paint was applied, indicating that it was indeed a finish layer.

The second generation was a polychrome scheme. The evidence suggests that the baseboards were painted black and varnished, the stringers were painted a dark brown color, and the balusters, newel posts and handrails were painted with a green paint that contained verdigris. This same color scheme is in place today, suggesting that some scraping may have been carried out at some point.

In the third generation, the verdigris-green paint was re-applied to those elements that were green in the second generation, the baseboards were painted dark brown, and the stringers were left dark brown, not receiving a new layer of paint.

In later generations, the stringers, newel posts, and balusters were painted a variety of light gray, white, and off-white colors. Even the baseboards were painted white in the majority of these generations. However, from the sixth generation onwards, the handrail was decorated with a series of boldly-colored imitation wood graining finishes, matching what was found on the door leaves throughout the house.

9| Generation | Description | Observations |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | stair stringers unpainted (dark brown), baseboards dark brown, verdigris paint re-applied | matches dark brown door leaves and verdigris-green trim in hall |

| 2 | dark brown paint on stair stringers, black and varnished baseboards, verdigris-green on rest of stair | matches dark brown door leaves and verdigris-green trim in hall |

| 1 | light gray | paint found throughout house |

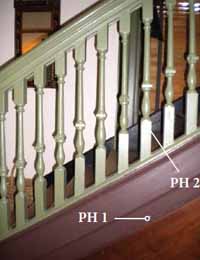

Palmer House Staircase

Palmer House Staircase — stringer

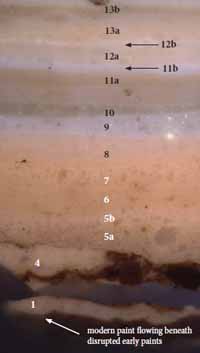

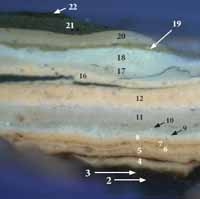

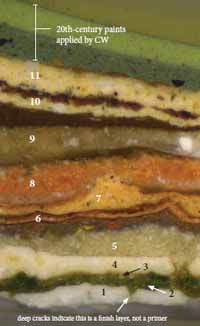

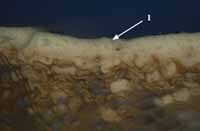

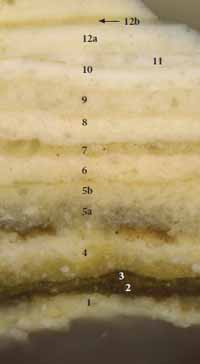

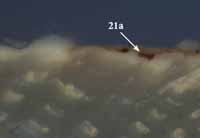

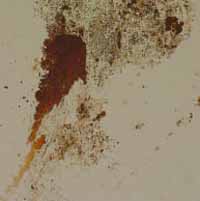

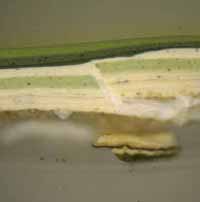

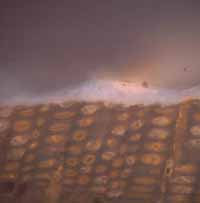

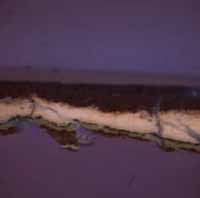

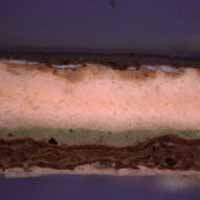

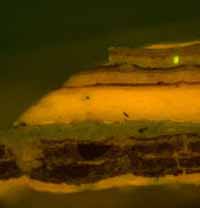

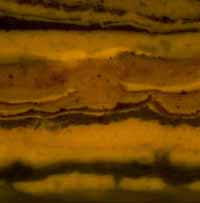

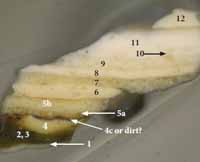

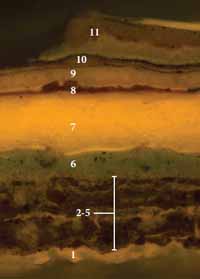

Sample PH 1: west face of bottom stringer, first floor (detail from previous page)

Comparison of sample PH 1b with other samples collected from the staircase suggests that this element was not painted in the third generation, and that the dark brown second generation was left exposed.

Palmer House Staircase — balusters

Sample PH 2: 15th baluster up from bottom, base

This sample from the baluster is missing the first two paint generations, but comparison of this sample with stringer sample PH 1b (previous page) suggests that from generations 4 - 20, the stringer and banisters were painted the same white or off-white colors. In generation 21 and later, the baluster was painted green and the stringer was painted dark brown. These later paints were most likely applied by CWF.

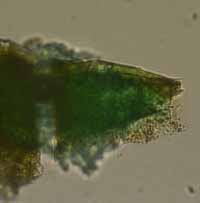

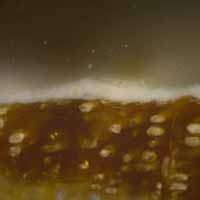

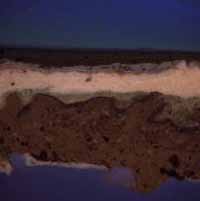

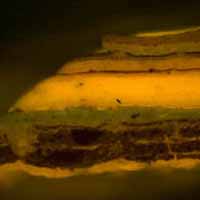

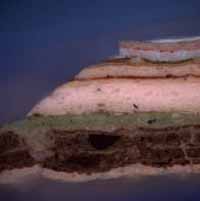

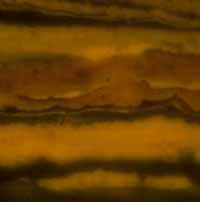

Sample PH 3: 2nd baluster up from bottom, top of shaft

Sample PH 3 is shown here as it is a good example of the thickly applied second-generation green paint, whose complete lack of autofluorescence is characteristic for verdigris, a copper-based pigment. This paint contains large, coarsely ground verdigris particles and smaller white particles that could be lead white. The surface of this paint has discolored to a brown color, another characteristic of aged copper pigment-based finishes.

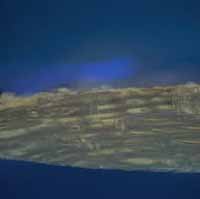

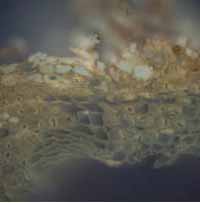

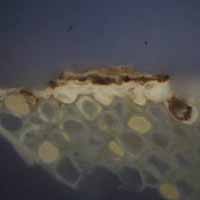

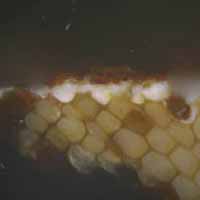

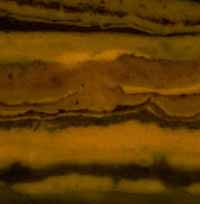

Sample PH 6: 2nd baluster up from newel post on second landing, top of shaft

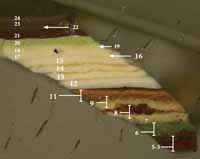

PH 6 illustrates that the first generation applied to the staircase is the light gray paint (which appears white in cross-section due to the intensity of the light source at high magnification). This is followed by the second- generation verdigris green paint, two layers of which are visible at higher magnifications (next page).

Palmer House Staircase — newel post

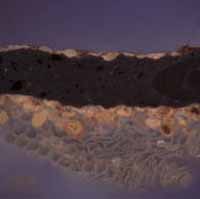

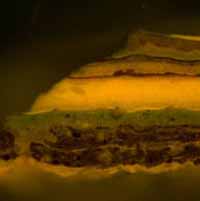

Sample PH 5: newel post on first stair landing, 30" up from bottom

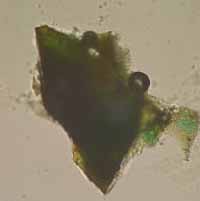

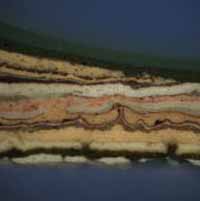

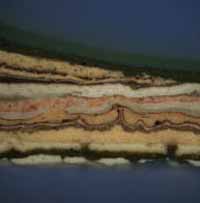

PH 5b, visible light, 100x (enlarged)

PH 5b, visible light, 100x (enlarged)

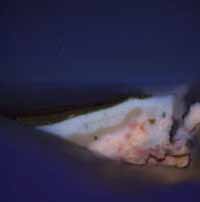

PH 5b, UV light, 100x (enlarged)

PH 5b, UV light, 100x (enlarged)

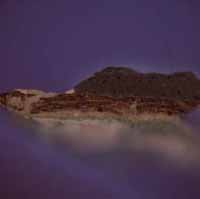

Sample PH 5 illustrates that the newel posts have the same paint history as the balusters (the modern paints are not shown). In the first generation the newels were painted with the same light gray paint found on the entire stair (this generation appears white in cross-section due to the intensity of the light source as high magnifications). In generations 2 and 3, the verdigris paint was applied to the newels. The thin, dark layer above generation 4 could represent a decorative glaze or an oxidized varnish applied over the cream-colored paint. This thin layer was also observed on the balusters (PH 6 and PH 2). The exact nature of this layer cannot be determined through cross-section microscopy alone.

Palmer House Staircase- handrail

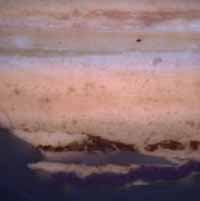

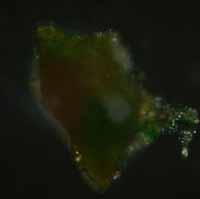

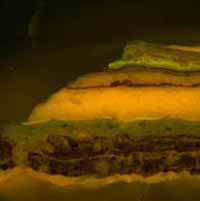

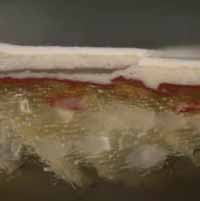

Sample PH 28: handrail fascia, second floor landing

Sample PH 28: handrail fascia, second floor landing (detail)

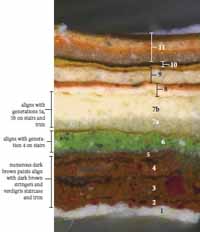

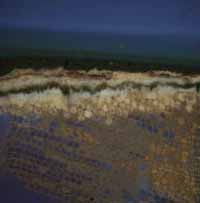

The deep cracks in generation 1 (previous page), into which the second generation paint flows, is a clear indication that generation 1 was an independent finish, not a priming layer. Two generations of verdigris paints are present (generations 2 and 3). Generation 4 is a cream-colored paint that aligns with the rest of the woodwork on the stair, as is generation 5. In generations 6 - 11, the handrail was painted to imitate wood grain, while the rest of the stair was painted white or off-white colors. These same decorative wood graining finishes were also found on the cellar door leaf in the entry hall.

Palmer House Staircase- baseboard

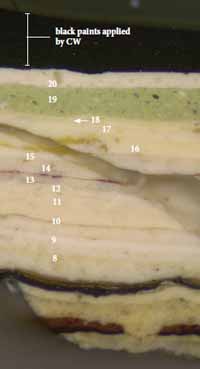

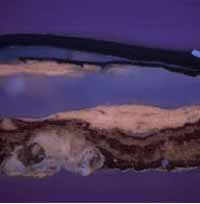

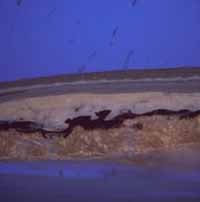

Sample PH 26: baseboard, east wall

The second-generation black paint on the baseboards aligns with the verdigris paint on the balusters, handrail, and newel post and the dark brown paint on the stringers. In the third generation, the baseboards were painted dark brown, possibly to match the stringers, which were left unpainted.

Many of the later paints on the baseboard align with those found on the rest of the staircase, suggesting that the entire stair was painted white with faux-grained handrails during those periods.

Sample PH 26: baseboard, east wall (detail of earliest layers)

First Floor, Entry Hall, Cellar Door (Under Stairs )

Description:

The four-panel cellar door leaf under the stairs is reported to be original to the house (Douglas 1956, 21). It had been relocated before the restoration, and is now restored to its rightful place. In-situ, the architrave was examined and it appeared to be old as well, having substantial accumulations of paint. The hinges are reproduction. Currently, the door is painted dark red-brown with olive-green trim. The paint schedule for the first floor hall reports that this door leaf was painted red brown #773 with dark green trim #827 (Douglas 1956, 37).

When examined, the cellar side of the door leaf did not appear to contain as many generations of paint as the hall side, and the trim looked new.

Results:

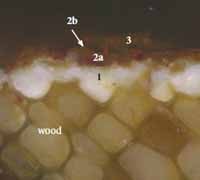

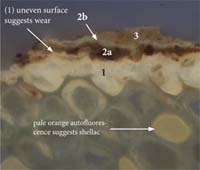

Three samples were collected from the door leaf under the stairs (PH 17 - PH 19), and one was collected from the architrave and the hall side (PH 20). One sample was collected from the cellar side of the door leaf (PH 21).

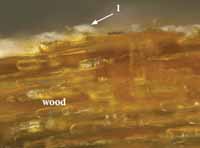

In the first generation, both sides of the cellar door leaf and the door architrave on the hall side were painted with the same light gray paint used on the stairs. In sample PH 19b, the surface of this paint is uneven and worn, again suggesting this was a finish layer, not a primer.

In the second generation, both sides of the door leaf were painted dark brown and varnished (although the cellar side evidence is fragmentary and questions remain), while the architrave was painted with a verdigris- green paint. This scheme matches the verdigris paint on the main stair in this period.

In the third generation, the door leaves were again painted dark brown and the trim was re-painted with the verdigris green paint. Again, this same scheme was found on the staircase.

Following the early verdigris green paint generations, the architrave was painted with various shades of gray, white, and off-white colors for most of its decorative history, similar to the staircase. In fact, the architrave sample (PH 20), has a very similar stratigraphy to the staircase balusters (PH 2 and PH 6).

The hall side of the door leaf was painted dark brown and varnished repeatedly in its early history, from generations 2-5. By comparison, generation 7 on the door leaf aligns strongly with generation 5 on the architrave, suggesting that the door leaf was painted with more frequency than the trim. Each dark brown paint layer exhibits substantial disruption and accumulations of grime on their surfaces, suggesting that frequent use may have been behind the constant re-painting. Following the dark brown paint generations, the door was painted a bright green color and varnished in generation 6. This may have aligned with the fourth generation white paint on the trim.

Shortly thereafter, the door leaf was painted with a series of brightly-colored imitation wood graining finishes that align with those found on the staircase handrail. The door architrave continued to be painted white or off-white. Therefore, during these periods, the entry hall scheme would have been white trim with faux-grained door leaves while the stair was painted white with a faux-grained handrail to match the leaves. This is suggestive of a late 19th-century or early 20th-century decorative scheme.

23| Generation | Description | Observations |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | dark brown paint and varnish on leaf, verdigris-green trim | matches dark brown stringers and verdigris-green balusters, newels, and handrail |

| 2 | dark brown paint and varnish on leaf, verdigris-green trim | matches dark brown stringers and verdigris-green balusters, newels, and handrail |

| 1 | light gray paint on leaf and trim | found throughout house |

Sample Locations: First floor, entry hall, cellar door (under stairs)

First floor, entry hall, cellar door under stairs

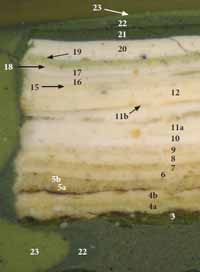

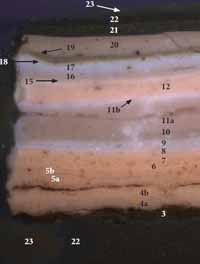

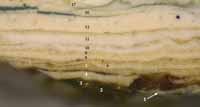

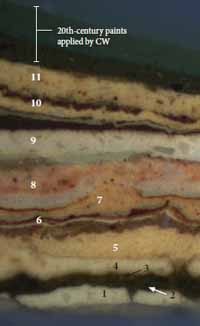

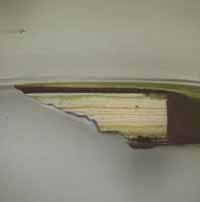

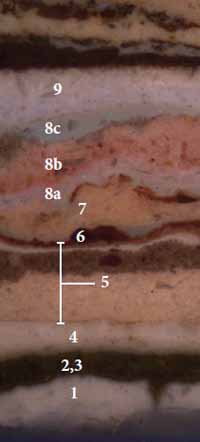

Sample PH 18a: bottom edge of lower right raised panel

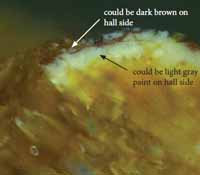

Although the wood substrate and generations 1 and 2 are missing, sample PH 18 nevertheless contains one of the most intact stratigraphies spanning from what could be the colonial period to the present day. The earliest layers are shown and discussed in more detail on the next page.

First floor, entry hall, cellar door under stairs (hall side)

Sample PH 19: lower right raised panel, lower left corner, 3" up from bottom

Sample PH 20: cellar door architrave

This sample is comparable to those taken from the stair balusters and newel posts (PH 2 and PH 5), suggesting that all of the trim in the entry hall might have been painted the same color throughout their decorative history.

First floor, entry hall, cellar door under stairs (cellar side)

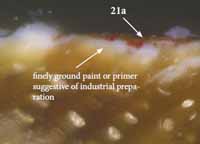

Sample PH 21: cellar door leaf, lower left panel

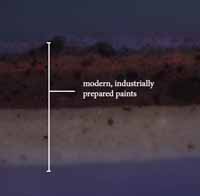

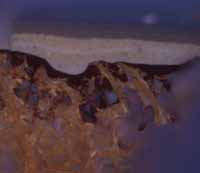

On-site examination suggested that the cellar side of the door leaf did not contain as many finishes as the hall side. The cross-section confirms this observation. On a fragment of wood substrate, what could be the first-generation light gray was observed, as were remnants of what appear to be the second-generation dark brown paint with an autofluorescent varnish coating, but it was not possible to definitively identify these paints as generations 1 and 2 on the hall-side of the leaf. The remainder of the sample contained only modern, industrially prepared paints.

First Floor, Living Room (North Room), Closet Door Leaf

Description:

The closet on the west wall of the living room was constructed during the restoration, based on evidence that suggested a closet had originally been located there (Douglas 1956, 25). All of the closet woodwork is new except the six-panel door leaf, original to the house, having been found in the attic (Ibid.). However the report does not clearly state what evidence there was that suggested this door originates from the living room. On-site examinations found substantial paint accumulations exist on the room-side, but the closet-side appears to have lost its original paint history (Chappell 2011, sample memo).

The door leaf is currently painted dark red-brown with olive-green trim. The report paint schedule for this room states that the woodwork is to be painted dark green #827, "the same as the living room" (Douglas 1956, 38). This would appear to be a misprint, as no modern green paints were found on the door. The report also states "all other doors downstairs except in the kitchen are dark brown #773 (Douglas 1956, 37). This is more in keeping with what was found on the door in this analysis.

Summary of results:

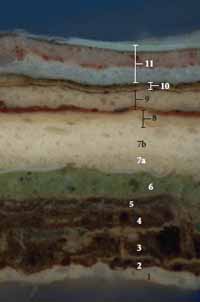

Three samples were collected from the room-side of the door leaf (PH 13, 14, and 15). The evidence shows that the first seven generations of paint clearly align with those on the cellar door leaf in the entry hall (PH 19). The first generation is a light gray paint, whose worn and uneven surface indicates it was indeed a finish layer (PH 15). This is followed by repeated applications of dark brown paints with varnishes from generations 2-5. These paints appear disrupted and have substantial accumulations of grime separating the layers, like the cellar door. In the sixth generation, the door was painted with a gray base coat (6a), bright green paint (6b), and varnish layer (6c).

After the sixth generation, the door leaf was painted with various shades of gray and off-white, some of which align with paints found on the entry hall trim and stair. In contrast to the entry hall, where in later years the cellar door leaf and stair handrail were repeatedly painted to imitate wood grain, only one faux-wood graining generation (generation 10), was observed in the samples collected from this door leaf. This is immediately followed by modern, industrially prepared red-brown paints, most likely applied by CWF. Since the report states that this door was found in an attic, it is possible that this leaf is missing later wood-graining generations because it had been de-installed at that time.

| Generation | Description | Observations |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | dark brown paint with varnish | matches other original door leaves on first and second floors |

| 2 | dark brown paint with varnish | matches other original door leaves on first and second floors |

| 1 | light gray paint on leaf and trim | found throughout house |

Sample locations; Palmer House, first floor, living room, closet door

Palmer House, first floor, living room, closet door leaf

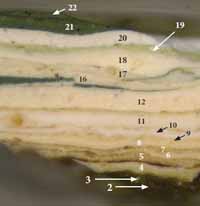

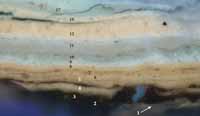

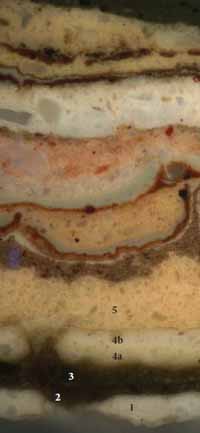

Sample PH 14: center left panel, bottom right corner, chamfered edge

The paint history found on the living room door leaf is comparable to the cellar door in the entry hall (PH 19) and the second-floor bedroom closet door (PH 11 and PH 31). This suggests that in the earliest generations, the leaves on the first and second floors were painted in a similar manner.

First Floor, Entry Hall, Rear (South) Door

Description:

The rear door leaf is reported to be original to the house and is suggested to have its original HL hinges (Douglas 1956, 12). In-situ, the door leaf was examined and did not appear to have any old paint evidence, although a ¼" ribbon of 'ghosting' was visible around the inner perimeter of the panels, suggestive of some type of painted decorative border beneath successive layers of paint. However, numerous micro-excavations with a scalpel and hand-held magnifier did not reveal more than one or two modern paint layers. The same conditions were found on the architrave, although approximately twenty-five generations were found on the exterior side of the leaf (Loeblich 2007, 13).

Currently, the door is painted red-brown with olive-green trim. The paint schedule for the first floor hall reports that the rear door leaf was painted dark green #827 in a satin finish (Douglas 1956, 37). As with the living room door leaf, this would appear to be a misprint, as no modern green paints were found on the door.

Summary of results:

Since multiple micro-excavations failed to find evidence of early paints on this side of the door leaf, only one sample was collected (PH 16), in the hope of finding early material embedded deep in the wood substrate. This sample was collected from the "paint ghost" around the inner perimeter of an upper panel.

This sample found no evidence of historic finishes on the hall-side of the south (rear) door leaf. The first paint generation is a white, finely ground paint or primer that appears industrially prepared. This is followed by at least five generations of what appear to be 20th-century red-brown paints that align with the later paints on the stair in the hall. These are the red-brown paints that have been applied by CWF since the restoration. Because of this evidence, it would appear that the historic finishes were stripped from this side of the door, possibly during the restoration. It is unclear why the finishes on the exterior-side were not removed as well.

Sample locations; Palmer House, first floor, entry hall, south (rear) door

Palmer House, first floor, entry hall, south (rear) door leaf

Sample PH 16: top left panel, bottom left corner

PH 16b, visible light, 200x (enlarged)

PH 16b, visible light, 200x (enlarged)

PH 16b, UV light, 200x (enlarged)

PH 16b, UV light, 200x (enlarged)

Although this is an original door leaf, and twenty-five paint generations were identified on the exterior-side (Loeblich 2007, 12), the interior-side does not appear to retain any historic finishes. The earliest layer is a finely ground white paint or primer that appears to have been industrially prepared. This is followed by at least five dark brown paints generations that appear to be 20th-century paints, most likely applied by CWF since the restoration. These findings suggest that the door was scraped or stripped of its historic finishes.

Second Floor, North Bedroom, Closet Door Leaf

Description:

The architectural report states that the closet door in the northwest bedroom is original (Douglas 1956, 33). It is a six panel door with raised panels on the room-side and a plain, inferior construction on the closet-side. It was used as the model for all of the second-floor doors. The report refers to this room as "bedroom #1," and its paint colors are recorded as 'gray-green # 101' with the closets painted similarly (Douglas 1956, 29, 38). Today, the closet door is painted dark brown. During sampling it was noted that this door retains substantial accumulations of paint, much of which is cracked extensively in an 'alligatoring' pattern, possibly from heat exposure. On-site excavation suggests that fewer generations are present on the closet side.

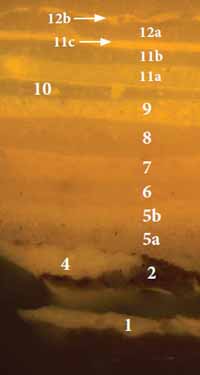

Summary of results:

Six samples were collected from the door leaf. Samples PH 8, PH 12 and PH 29 -PH 31 were collected from the room side, while sample PH 11 was collected from the inferior closet side. Many of these showed heavily disrupted stratigraphies with missing paint layers, and are not discussed here.

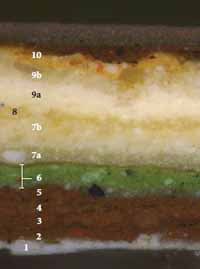

Samples PH 31 (room side) and PH 11 (closet side) indicate that both sides of the door were painted in the same manner from generations 1-6, although the first generation light gray paint was found on the closet side, but not the room-side of the door. However, the painted surface was particularly disrupted and it may have been lost from the room side.

On both sides of the door, generations 2-5 are multiple applications of red-brown paints, and generation 6 consists of a gray base coat, green paint, and varnish layer. The sample taken from the ogee on the room side (PH 31), exhibits a much darker green paint in this generation, which suggests that the door was bright green with dark green ogees in this period. These first six generations are also the same as those found on the door leaves on the first floor, suggesting that the door leaves on the first and second floors were painted in the same manner in the early history of the house.

| Generation | Description | Observations |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | dark brown paint with varnish | matches other original door leaves on first floors |

| 2 | dark brown paint with varnish | matches other original door leaves on first floors |

| 1 | light gray paint on leaf and trim | found throughout house |

Sample locations; Palmer House, second floor, north bedroom, closet door

Sample PH 31: room side of leaf, second stile from top, top ogee

Cellar

Description:

The cellar-side of the entry door in the stair passage is painted dark red-brown with green trim, like the hall side. The trim appears to be new, but the door is old, although on-site examination suggests that fewer layers of paint appear to be present on this side of the leaf, compared to the opposite side.

The architectural report states that the doors in the cellar are all new (Douglas 1956, 18), this appears to include both the leaves and the trim, but is not specified. On-site examination by Edward Chappell suggests that the frame of the leftmost (south) door frame on the north-south partition could be original. On-site micro-excavation found one thin red-brown paint followed by what appear to be a few layers or modern white paints. However, this same paint history was also found on the north door frame, which is known to be new. The architectural report states that all woodwork in the cellar is to be painted flat white. The present color is a glossy white.

Results:

Three samples were collected from the cellar door frames along the north-south partition wall. Samples PH 22 and PH 24 were collected from the left (south) door frame, and for comparative purposes one sample, PH 23, was collected from the right (north), door frame, known to date to the restoration (1950). One sample, PH 25, was also collected from the surface of an exposed beam running along the east wall of the cellar stairway. Flaking accumulations of limewash appeared to have been applied to this element.

The samples from the cellar contain little information relating to the finish history of this space. Both the old and new door frames retain the same paint history consisting of one red and two white paint generations, all of which appear to be modern. This would suggest that the older frame was never painted, although there was no accumulation of grime that would be expected on a surface left exposed for over two centuries.

Approximately seven generations of limewash were found on the beam along the east cellar stair wall. One of these coatings, labelled generation 2, is a light yellow-tan color but it could not be determined if this was a deliberately pigmented limewash or an accidental deposit of some type (it was not consistently applied to the entire beam, although this could also result from deterioration and loss).

Sample locations: Cellar

cellar, south (left) door at north-south partition wall

cellar, south (left) door at north-south partition wall

cellar, south door viewed from the west room

cellar, south door viewed from the west room

cellar, beam running along east stair wall

cellar, beam running along east stair wall

No photo of north (right) door in north-south partition wall

Cellar door frames

Sample PH 22 and PH 23, north south partition wall, south frame (PH 22) and north frame (PH 23)

The sample taken from the old door frame (top), in comparison with the sample taken from the new door frame (bottom), indicates that both surfaces have the same paint history. The wood surface of the older frame is very disrupted, but there is no accumulation of dirt as would be expected on a surface left unpainted for over two centuries. The wood substrate in sample PH 23 is clearly new, clean, and unoxidized.

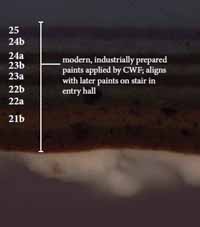

Cellar stair beam

Sample PH 25: surface of beam on east cellar stair wall

PH 25b, visible light, 200x (enlarged)

PH 25b, visible light, 200x (enlarged)

PH 25b, UV light, 200x (enlarged)

PH 25b, UV light, 200x (enlarged)

PH 25a, visible light, 200x (enlarged)

PH 25a, visible light, 200x (enlarged)

PH 25a, UV light, 200x (enlarged)

PH 25a, UV light, 200x (enlarged)

The yellow-tan colored layer on the bottom of sample PH 25b was observed in-situ to be very thick with a great deal of sandy aggregate, vestiges of which cling the beam. This could represent an accidental deposition of a masonry material (perhaps a plaster repair), rather than a deliberately pigmented layer applied to the beam. A more confident assessment of this layer could not be made.

Counting the yellow layer, approximately seven limewash generations were identified. Remnants of a limewash were also observed on the wood substrate, with visible grime its the surface. This suggests that successive layers of limewash are missing from this sample, most likely having cleaved from the surface due to the inherent brittleness of this type of coating.

Binding Media Analysis Results

Summary:

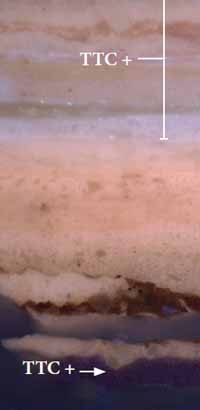

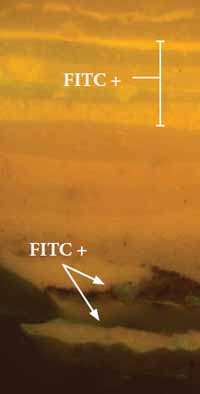

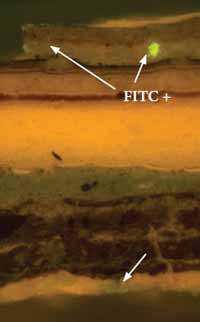

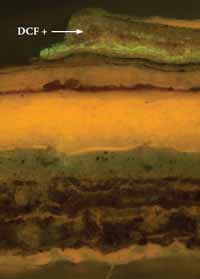

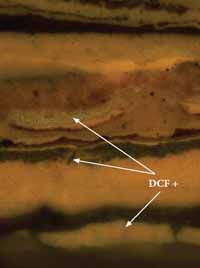

In the majority of samples, fluorochrome staining reactions were faint and difficult to interpret, and did not provide conclusive evidence pertaining to the medium of the earliest paints. However, in sample PH 28, a positive reaction for oils with DCF was observed in the first generation light gray paint.

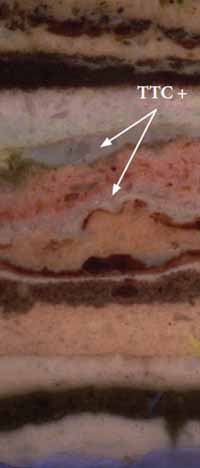

In sample PH 1 (staircase stringer), generations 9-12 stained positively with TTC, FITC, and DCF. Most likely these are 'false positives' resulting from detergents and cellulosic bulking agents added to industrially prepared paints. Although in cross-section the first generation light gray has the characteristics of a traditional oil-bound paint, no reactions for lipids (oils) with DCF were observed. However, a positive FITC reaction was observed, which could suggest that a proteinaceous material, such as animal glue, was used to disperse the pigments during grinding. Similar reactions were observed in the second generation dark brown paint, which stained positively for FITC, while TTC and DCF reactions were negative.

In sample PH 19 (entry hall, door to cellar), positive reactions with all three stains were observed in generation 11, which appear to be 'false positives' generated by industrially prepared paints. Faint, "splotchy" reactions for proteins with FITC and oils with DCF were observed in some of the earliest paints, but these do not appear to be true reactions.

In sample PH 28 (staircase handrail), a positive reaction for oils was observed in the first generation light gray paint, suggesting it is oil-bound. Later, industrially prepared paint generations exhibited 'false positives' seen in the other samples.

Binding media analysis results

Sample PH 1b: staircase, bottom stringer

PH 1b, UV light, 200x

PH 1b, UV light, 200x

Before TTC stain

PH 1b, UV light, 200x

PH 1b, UV light, 200x

TTC reaction

Sample PH 1b was stained with TTC to tag carbohydrates in the earliest paints. A positive reaction (a dark reddish-brown color) was observed in the more recent paints (9-12b), most likely cellulosic bulking agents added to modern paint formulations.

Note that the positive TTC reaction at the bottom of the sample results from a modern paint that flowed under disrupted early paints.

PH 1b, B2A filter, 200x

PH 1b, B2A filter, 200x

Before FITC stain

PH 1b, B2A filter, 200x

PH 1b, B2A filter, 200x

FITC reaction

Sample PH 1b was stained with FITC to tag protein in the earliest paints. A positive reaction (a yellow-green fluorescence) was observed in generations 1 and 2, possibly resulting from a proteinaceous medium used to disperse pigments during grinding.

Positive reactions were also observed in some of the more recent paints, most likely detergents added to modern paint formulations.

Sample PH 1b: staircase, bottom stringer

PH 1b, B2A filter, 200x

PH 1b, B2A filter, 200x

Before DCF stain

PH 1b, B2A filter, 200x

PH 1b, B2A filter, 200x

DCF reaction

Sample PH 1b was stained with DCF to tag lipids (oils) in the earliest paints. No reactions in the earliest paints were observed. This could suggest that these paints were leanly bound.

Positive reactions were observed in some of the more recent paints, (generations 9-11), possibly resulting from detergents and other additives in modern paint formulations. This reaction could also indicate that these are alkyd paints.

Sample PH 19b: entry hall, cellar door (leaf), under stairs

PH 19b, UV light, 200x

PH 19b, UV light, 200x

Before TTC stain

PH 19b, UV light, 200x

PH 19b, UV light, 200x

TTC reaction

Sample PH 19b was stained with TTC to tag carbohydrates in the earliest paints. Positive reactions (a dark reddish-brown color), were observed in one of the later wood graining generations (11), possibly resulting from cellulosic bulking agents added to industrially prepared paints.

PH 19b, B2A filter, 200x

PH 19b, B2A filter, 200x

Before FITC stain

PH 19b, B2A filter, 200x

PH 19b, B2A filter, 200x

FITC reaction

Sample PH 19b was stained with FITC to tag proteins in the earliest paints. A faint 'splotchy' positive reaction was observed in generation 1, which appears to be residual stain left behind in gaps in this paint, and is not a true reaction.

A 'splotchy' positive reaction was also observed in generation 11, most likely a false positive generated from detergents and other additives in industrially prepared paints.

Sample PH 19b: entry hall, cellar door (leaf), under stairs

PH 19b, B2A filter, 200x

PH 19b, B2A filter, 200x

Before DCF stain

PH 19b, B2A filter, 200x

PH 19b, B2A filter, 200x

DCF reaction

Sample PH 19b was stained with DCF to tag lipids (oils) in the earliest paints. A strong positive reaction was observed in one of the later wood graining generations (11), which also stained positively for proteins (FITC +), and carbohydrates (TTC +), suggesting that these reactions are 'false positives' generated by additives in industrially-prepared paints.

Some faint, 'splotchy' fluorescence was observed in generations 1-6, but these appeared to be stain residues left in depressions in the paints, and have not been interpreted as true reactions.

Sample PH 28a: entry hall, cellar door (leaf), under stairs

PH 28a, UV light, 200x

PH 28a, UV light, 200x

Before TTC stain

PH 28a, UV light, 200x

PH 28a, UV light, 200x

After TTC stain

Sample PH 28a was stained with TTC to tag carbohydrates in the earliest paints. Positive reactions (a dark reddish-brown color), were observed in later generations 8a and 8c, most likely cellulosic bulking agents added to industrially prepared paints.

PH 28a, B2A filter, 200x

PH 28a, B2A filter, 200x

Before FITC stain

PH 28a, B2A filter, 200x

PH 28a, B2A filter, 200x

After FITC stain

Sample PH 28a was stained with FITC to tag proteins in the earliest paints. No reactions (a yellow-green fluorescence), were observed.

Sample PH 28a: staircase, handrail

PH 28a, B2A filter, 200x

PH 28a, B2A filter, 200x

Before DCF stain

PH 28a, B2A filter, 200x

PH 28a, B2A filter, 200x

DCF reaction

Sample PH 28a was stained with DCF to tag lipids (oils) in the earliest paints. Positive reactions were observed in generations 1, 5b, and 8a, and 9. This suggests that the first generation light gray paint was oil-bound. The weakness of the previous reactions could result from deterioration of the binding media, or suggests that this paint was leanly bound.

Pigment identification results

Summary:

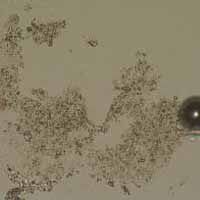

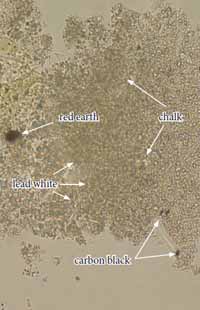

Pigments in the earliest paint generations were identified using polarized light microscopy (PLM) techniques. Pigment samples were collected with a clean scalpel blade from the uncast portions, dispersed on a glass slide, and mounted with Cargille Meltmount (refractive index 1.66) and examined in plane polarized transmitted light and cross polarized transmitted light.

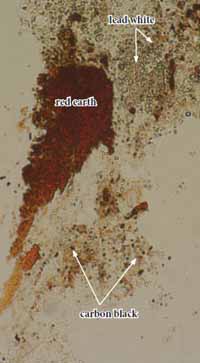

The results indicate that the first generation light gray paint seen throughout the house is composed primarily of lead white (2PbCO3 ‧ Pb(OH)2), chalk (CaCO3), carbon black (C), and a very small amount of red earth pigment (Fe2O3).

The second generation dark brown paint applied to the door leaves and the stair stringers is composed of red earth pigment (Fe2O3), and carbon black (C). Some lead white was included in this sample, which most likely is a contaminant from surrounding paint layers.

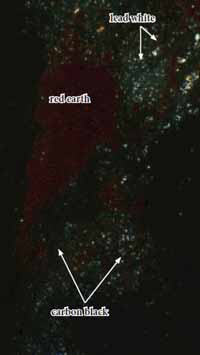

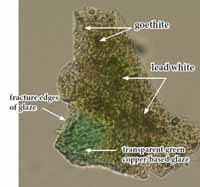

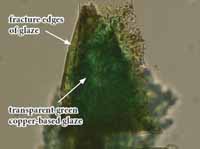

The second generation green paint on the stair balusters, newel posts and handrails, as well as the door architraves appears to be a verdigris-based paint coated with a copper-based glaze in which particles of lead white (2PbCO3 ‧ Pb(OH)2), and yellow earth (Fe2O3 ‧ nH2O), were suspended. While large discrete verdigris particles were observed in cross-section, these were not seen in the dispersed pigment sample. Instrumental techniques such as FTIR or Raman spectroscopy could be carried out to conclusively identify verdigris, and organic media analysis with gas-chromatography mass-spectrometry (GC-MS), could determine if this is a copper-resinate glaze or verdigris pigments ground in a drying oil.

Pigment Identification Results

Generation 1 light gray paint on all woodwork

Dispersed pigments from sample PH 28, generation 1

Dispersed pigments from sample PH 28, generation 1

light gray paint, transmitted plane polarized light, 1000x

Dispersed pigments from sample PH 28, generation 1

Dispersed pigments from sample PH 28, generation 1

light gray paint, transmitted cross polarized light, 1000x

The first generation light gray paint is mostly comprised of lead white (2PbCO3 ‧ Pb(OH)2), which appears as small, rounded colorless to green particles that are birefringent (bright) under crossed polars. Some chalk (CaCO3), was also present, visible as thin plates with strong interference colors. A small amount of red earth (Fe2O3), was also present, visible as particles with a deep red color in transmitted light that are isotropic (dark) in crossed polars. In cross-section, occasional red particles were seen in this paint, so this is not a contaminant from another layer. The addition of red ochre would have lent the gray a warmer tone. Although fine black particles were seen dispersed throughout this paint in cross-section, only a few particles of carbon black were present in this sample.

underside of uncast portion of sample

underside of uncast portion of sample

PH 28 showing early paints, 100x

Generation 2 red-brown paint on stair stringers and door leaves

Dispersed pigment sample from sample PH 1, generation 2, transmitted plane polarized light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from sample PH 1, generation 2, transmitted plane polarized light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from sample PH 1, generation 2, transmitted cross polarized light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from sample PH 1, generation 2, transmitted cross polarized light, 1000x

A sample of the second generation dark brown paint was collected from the uncast portions of PH 1, dispersed on a glass slide, and mounted with Cargille Meltmount (refractive index 1.66) for polarized light microscopy.

The pigments were identified as a mixture of an isotropic red earth (Fe2O3), and carbon black pigments (C). The sample also contains lead white (2PbCO3 ‧ Pb(OH)2), appearing as small colorless grains that are highly birefringent (bright) under crossed polars, but these could originate from one of the adjacent paints.

Generation 2 green paint on stairs and trim

Dispersed pigment sample from sample PH 3, generation 2, transmitted plane polarized light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from sample PH 3, generation 2, transmitted plane polarized light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from sample PH 3, generation 2, transmitted cross polarized light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from sample PH 3, generation 2, transmitted cross polarized light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from sample PH 3, generation 2, transmitted plane polarized light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from sample PH 3, generation 2, transmitted plane polarized light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from sample PH 3, generation 2, transmitted cross polarized light, 1000x

Dispersed pigment sample from sample PH 3, generation 2, transmitted cross polarized light, 1000x

This sample contained large, brittle flakes of a transparent deep emerald-green color, which were isotropic (dark) under crossed polars.This is suggestive of a copper-based glaze made with oil or resin (Kuhn 1984, 150). Small, colorless grains of lead white (2PbCO3 ‧ Pb(OH)2), and goethite, yellow minerals associated with yellow earth pigments (Fe2O3 ‧ nH2O), were also seen suspended in the matrix of the glaze. Discrete particles of verdigris were not found (tabular particles with an intense blue-green color and bright birefringence), although they were seen in cross-section. These findings are very similar to the verdigris finish found in the first-floor chamber at Gunston Hall (Travers 2011, 9).

Color Measurement Results

Generation 1 light gray paint found on all woodwork

PH 28, staircase handrail, visible light, 100x

PH 28, staircase handrail, visible light, 100x

underside of uncast sample showing earliest paints

Accurate color readings for the first generation light gray paint could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter colorimeter/microscope, possibly because this finish was quite fragmented and a large, intact area could not be exposed for measurement. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest commercial color match was determined to be Benjamin Moore swatch HC-172 "Revere Pewter."

Benjamin Moore

Benjamin Moore

HC-172

"Revere Pewter"

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 78.52 | -0.55 | +6.97 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 4.1Y | 7.8 | 1.0 |

Generation 2 dark brown paint on door leaves and stair stringers

PH 15, living room closet door leaf, visible light, 100x. Underside of uncast sample showing earliest paint.

PH 15, living room closet door leaf, visible light, 100x. Underside of uncast sample showing earliest paint.

The second generation dark brown paint in sample PH 15 was measured with a Minolta Chroma Meter colorimeter/ microscope to obtain color values in CIE L*a*b* and Munsell colorspace. To compensate for the inherent color variation in early hand ground paints, the average of two readings was determined.

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| area 1 | 30.04 | + 6.41 | + 6.67 |

| area 2 | 29.76 | + 5.53 | + 6.55 |

| average | 29.90 | + 5.97 | + 6.61 |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| area 1 | 2.0YR | 2.9 | 1.6 |

| area 2 | 3.2 YR | 2.9 | 1.5 |

The closest commercial color match was determined to be Colonial Williamsburg swatch CW 115 "Tucker House Chocolate." The color difference (ΔE) between this swatch and the brown paint was calculated to be 5.59. The average human eye cannot detect ΔE values less than 3, but values < 6 are considered acceptable matches in the printing industry. Therefore, CW "Tucker House Brown" is an acceptable match for the second generation paint.

58 C. Williamsburg

C. Williamsburg

#115

"Tucker House

Chocolate"

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* | a* | b* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26.25 | +3.40 | +3.24 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 1.6YR | 2.5 | 0.8 |

Generation 2 black paint on stair baseboards

PH 26, staircase baseboard, visible light, 100x. Underside of uncast sample showing earliest paints

PH 26, staircase baseboard, visible light, 100x. Underside of uncast sample showing earliest paints

Accurate color readings for the first generation light gray paint could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter colorimeter/microscope because a large, intact area could not be exposed for measurement. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest match was determined to be Colonial Williamsburg #123 "Mopboard Black." It should also be noted that the Palmer House black paint was very glossy.

C. Williamsburg

C. Williamsburg

#123

"Mopboard black"

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* | a* | b* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18.73 | +0.36 | -1.93 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 5.4PB | 1.8 | 0.4 |

Conclusions:

This study found substantial paint evidence on original woodwork in the Palmer House from which the earliest decorative schemes can be postulated.

The first generation applied to all woodwork on the first and second floors was a light gray paint. This paint was found in samples taken from the entry hall (staircase, door leaves and trim), the closet door leaf in the first-floor living room, and the closet door on the second floor. The analysis determined that this is an oil-bound paint made with lead white, chalk, carbon black and a small amount of red ochre, which resulted in a light gray color with a reddish hue. As the first generation, this finish would date to the John Palmer period (1754-1760). In some samples, the surface of this paint was worn and cracked, suggesting that it was exposed for an extended period of time, possibly after Palmer's death and into the period of tenancy (1760-1780). A commercial color match for this paint is provided on page 55.

In the second generation, the woodwork received a polychrome scheme of dark brown, green, and black colors. The door leaves and stair stringers were painted dark brown and varnished. This brown paint was made with red earth and carbon black pigments but binding media analysis was inconclusive. It has a distinct reddish tone, and may have been referred to as "Chocolate Brown" in the 18th century (Bristow 1996, 157). A color match for this brown is provided on page 57. Meanwhile, the trim and stair balusters, newel posts, and handrail were painted a deep green color consisting of a green paint made with verdigris, which was then coated with a copper-based glaze ground with lead white and a small amount of yellow earth pigment. This finish has oxidized to a brown color, characteristic of finishes containing copper-based pigments, and a color match could not be determined. The stair baseboards were painted black and varnished. A color match is provided on page 58. These varnishes and resinous finishes would have lent the woodwork a very glossy appearance during this period. A precise date for this scheme could not be determined, but it is interesting to note that the apothecary John Galt, who occupied the house in 1769, regularly imported painter's materials, including verdigris, for sale in his shop. However, there is no physical evidence linking Galt to any of the Palmer House finishes.

In the third generation, the verdigris-based green and the dark brown paints were re-applied, and the baseboards were changed from black to red-brown. The stair stringers were left unpainted during this period, and would have remained red-brown.

The comparative paint evidence determined that the door leaves on the first and second floors were painted similarly in their early history, and that these finishes appear to coordinate with what was found on the main staircase in the entry hall. Following the earliest green and dark brown polychrome schemes, the stair baseboards, balusters, stringers, and newels were painted a variety of light gray, white, and off-white colors that aligned with the cellar door architrave. This was the only intact architrave in the house, but these findings suggest that all of the trim (window architraves, chair rails, cornices, etc.), could have been painted similarly. Contemporary with the light-colored trim, the stair handrail and door leaves were decoratively finished to imitate wood graining. These schemes may have spanned the early-19th to the early-20th centuries.

On the cellar door frames, only modern, 20th-century paints were found. The wood substrates lacked even the accumulation of grime which would be expected if these elements had been left unpainted originally. On the cellar stair beam, approximately seven generations on limewash were identified, but the grime above the first generation suggests that additional limewash layers may have been lost. This study was not able to elucidate the age or history of the cellar woodwork.

References

- Douglas, W. 1956. Palmer House architectural report, block 9, building 24, lot 27. Unpublished report for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Eastaugh, N., et. al. 2008. Pigment Compendium: a dictionary and optical microscopy of historical pigments. Oxford, Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Gettens, R., and G. Stout. 1942. Painting materials: a short encyclopedia. New York, Dover Publications, Inc.

- Kuhn, H. "Verdigris and Copper Resinate," chapter 6 in Artists' Pigments: a handbook of their history and characteristics, volume 2, Ashok Roy, ed., 1984. Oxford University Press, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.: 131-158.

- Loeblich, N. 2007. Cross-section microscopy analysis of exterior paints: John Palmer House. Unpublished report for the Architectural and Archaeological Research Department, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Stephenson, M. 1960. Palmer House historical report, block 9, building 24, lot 27. Unpublished report for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Travers, K. 2011. Cross-section microscopy analysis report: Gunston Hall, first-floor bedchamber closet. Unpublished report for the Architectural and Archaeological Research Department, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Whiffen, M. 1984, revised ed. The eighteenth-century houses of Williamsburg, Virginia. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Wolbers, R. 2008. Color and light. Lecture for General Conservation Science ARTC 615, at the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation.

Appendix A. Palmer House samples

| Sample | Location | Taken by/date |

|---|---|---|

| PH 1 | staircase, west face of bottom stringer, 35"up from floor and 68" from newel post, under the 15th baluster up from the bottom | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 2 | staircase, plinth of the 15th baluster up from the bottom, north face | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 3 | staircase, top of shaft of 2nd baluster up from the bottom | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 4 | staircase, bottom stringer, fascia, below the 3rd baluster up from the bottom | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 5 | staircase, first landing, newel post, west face, 30" up from bottom | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 6 | staircase, 2nd baluster up from the newel on the second landing (on the ascent), top of the shaft, west side | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 7 | staircase, second floor, top surface of newel post, north face just below the handrail, 33" up from bottom | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 8 | second floor, north bedroom, room-side of closet door leaf, right (hinged stile), 4" up from floor, adjacent to HL hinge | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 9 | staircase, second floor landing, south face of the handrail fascia, 1' out from the east wall | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 10 | staircase, baseboard adjacent window on the east wall, beneath the tread of the 9th stair up from the bottom | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 11 | second floor, north bedroom, closet door, closet-side of door leaf, lower right panel, top right corner | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 12 | second floor, north bedroom, closet door, room-side of door leaf, bottom ogee of second rail up from the bottom, far left edge under the handle | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 13 | First floor, living room, closet door leaf, room-side, bottom ogee of second rail from top, above the center right panel | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 14 | First floor, living room, closet door leaf, room-side, center left panel, bottom right corner, chamfered edge | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 15 | First floor, living room, closet door leaf, room-side, center of lock rail | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 16 | First floor, rear (south) entrance door, top left panel, bottom left corner | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 17 | First floor, entry hall, cellar entrance door under staircase, door leaf, hall-side, right stile, 5" up from bottom | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 18 | First floor, entry hall, cellar entrance door under staircase, door leaf, hall-side, lower right raised panel, bottom edge | Travers / May 2011 |

| PH 19 | First floor, entry hall, cellar entrance door under staircase, door leaf, hall-side, front surface of lower right raised panel, lower left corner, 3" up from bottom | Travers / June 2011 |

| PH 20 | First floor, entry hall, cellar entrance door under staircase, door architrave, inner side of left jamb, 52" up from bottom | Travers / June 2011 |

| PH 21 | Cellar, entrance door from hall, door leaf, cellar side, lower left panel, 24" up from bottom | Travers / June 2011 |

| PH 22 | Cellar stair entry space, north-south partition wall, frame of left (south) door, left jamb, east face, 38" up from floor | Travers / June 2011 |

| PH 23 | Cellar stair entry space, north-south partition wall, jamb of right (north) door (known to be new), 31" up from floor | Travers / June 2011 |

| PH 24 | Cellar, southwest room, frame of door on north-south partition (facing east, same door as PH 22 but opposite site), right jamb, 50" up from floor | Travers / June 2011 |

| PH 25 | Cellar, east wall along stairs, wood beam, 17" from left (north) end and 8" up from bottom | Travers / June 2011 |

| 63 | ||

| PH 26 | Staircase, baseboard along east wall at the 6th step, just under the junction of the stair window architrave and the east baseboard. | Travers / June 2011 |

| PH 27 | Staircase, baseboard along the west side of the staircase, under baluster #14 (not counting ½ baluster on newel) | Travers / June 2011 |

| PH 28 | Staircase, handrail at second floor landing, south face, same location as PH 9 | Travers / June 2011 |

| PH 29 | Second floor, north bedroom, closet door leaf, room side, lower left raised panel, under bottom edge at left corner | Travers / June 2011 |

| PH 30 | Second floor, north bedroom, closet door leaf, room side, bottom ogee of second rail up from the bottom, far left edge under the handle (same as PH 12) | Travers / June 2011 |

| PH 31 | Second floor, north bedroom, closet door leaf, room side, second stile from top, top ogee, 13" from left edge | Travers / June 2011 |

Appendix B: Procedures

Sample Preparation:

The samples were cast in mini-cubes of Extec Polyester Clear Resin (methyl methacrylate monomer), polymerized with the recommended amount of methyl ethyl ketone peroxide catalyst. The resin was allowed to cure for 24 hours under ambient light. After cure, the individual cubes were removed from the casting tray and sanded down using a rotary sander with grits ranging from 200 - 600 to expose the cross-section surface. The samples were then dry polished with silica-embedded Micro-mesh Inc. cloths with grits ranging from 1500 to 12,000, lending the final cross-section surface a glassy-smooth finish.

Microscopy and Documentation:

The cross-section samples were examined using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope equipped with an EXFO X-cite 120 fluorescence illumination system fiber-optic halogen light source. Samples were examined and photographed under visible and ultraviolet light conditions (330-380 nm), at 20 to 200x magnifications. Digital images were captured using a Spot Flex digital camera with Spot Advance (version 4.6) software. All images were recorded as 12.6 MB tiff files and stored on a hard drive in a folder titled "Palmer House Interior" on Susan Buck's laboratory computer. A separate set of images will be stored on the CWF digital database, accompanied by the appropriate metadata and a digital version of the final report.

Information Provided by Visible and Ultraviolet Light Microscopy:

When examining paint cross-sections under reflected visible and ultraviolet light conditions, a number of physical characteristics can be observed to assist with the interpretation of a paint stratigraphy. These include the number and color of layers applied to a substrate, the thickness or surface texture of layers, and pigment particle size and distribution within the paint film. Relative time periods for coatings can sometimes be assigned at this stage: for instance, pre-industrial-era paints were hand ground, lending them a coarse, uneven surface texture with large pigment particles that vary in size and shape. By contrast, more "modern", industrially-prepared paints have smoother, even surfaces and machine-ground pigment particles of a consistent size and shape. Furthermore, he presence of cracks, dirt layers, or biological growth between layers can indicate presentation surfaces and/or coatings that were left exposed for an extended period of time.

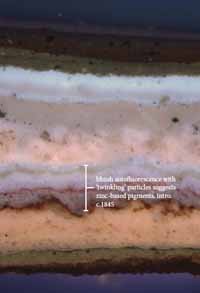

Under UV light conditions, the presence and type of autofluorescence colors can distinguish sealants, clear coatings, and binding media, from darker dirt or paint layers within the stratigraphy. For instance, shellacs exhibit a distinct orange-colored autofluorescence, while natural resins (such as dammar and mastic), typically fluoresce a bright white color. Oil media tends to quench autofluorescence, while most modern, synthetic paint formulations (such as latex) exhibit no fluorescence at all. Some pigments, such as verdigris, madder, and zinc white, have distinct fluorescence characteristics, as well. UV light microscopy is critical to help distinguish otherwise identical layers often found in architectural samples- such as successive varnishes, or multiple layers of unpigmented (white) limewash.

Binding Media Analysis using Fluorochrome staining:

Fluorochrome stains adapted from the biological sciences were used to characterize the paint binding media (oils, proteins, carbohydrates), in layers within the cross-section sample. The following stains were used in this analysis:

- 2,7 Dichlorofluorescein (DCF): 0.02% w/v in ethanol. Fluorescent labeling reagent for lipids, particularly drying oils. One drop of stain was applied to the surface of the sample, blotted immediately, and cover-slipped with mineral spirits. The reaction was observed with the B2A filter cube (EX 450-490nm, BA 520nm). This stain exhibits a yellow-green fluorescence where lipids are present.

- Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC): 1.0% w/v in ethanol. Labeling reagent for carbohydrates (gums, starches, cellulosic thickeners). One drop of stain was applied to the surface of the sample, blotted dry, and allowed to sit for approximately 45 seconds before cover-slipping, (must be allowed to react with atmospheric moisture for reaction to move forward). The reaction is observed under reflected UV light conditions (EX 330-380nm, BA 420nm). A dark red-brown color is seen where carbohydrates are present.

- Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC): 0.02% w/v in anhydrous acetone. Fluorescent labeling reagent for proteins. One drop of stain was applied to the surface of the sample, blotted immediately, and cover-slipped with mineral spirits. The reaction was observed using the B-2A filter cube (EX 450-490 nm, BA 520nm). A positive reaction is a bright yellow-green fluorescence.

Pigment Identification with Polarized Light Microscopy:

To collect a pigment sample for polarized light microscopy (PLM), a surgical scalpel was used to collect a small scraping from a clean, representative area of paint. The blade was then pressed and pulled across a clean glass microscope slide, dispersing the pigment particles across the surface. The pigments were then permanently embedded under a cover slip using Cargille Meltmount (refractive index 1.66). The embedded pigments were then examined in cross and plane-polarized transmitted light with the Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope at 1000x magnification (using an oil immersion objective). The observed morphologies (size, shape, agglomeration, cleavage patterns), and optical properties (including color, refractive index, extinction), were compared to reference standards as well as literature sources before making final determinations.

Color measurement and matching:

Color measurements were taken using the Minolta Chroma Meter CR-241 colorimeter/ microscope in Susan Buck's paint analysis laboratory. Equipped with an internal 360-degree pulsed xenon arc lamp, this instrument is capable of obtaining accurate color measurements in any one of five different tristimulus color measurement systems from areas as small as 0.3mm. For the purposes of this project, color values in CIE L*a*b* colorspace and the Munsell color system were obtained.

The CIE L*a*b* color space system (developed in 1976 by the Commission International de l'Eclairage, and now an internationally accepted industry-standard color measuring system) uses three numerical values, known as "tristimulus" values, to measure color: L* is the lightness variable, representing dark to light on a scale of 0-100, while a* and b* are chromaticity coordinates, a* representing red to green on scale from -50 to +50, and b*representing blue to yellow on a scale from -50 to +50. These three coordinates are used to plot the location of a color in the CIE L*a*b* colorspace.

66These resulting values can be used to quantify color differences (Δ E), between two samples. To obtain this value, the following calculation is used:

ΔE = (ΔL*)½ + (Δa*)½ + (Δb*)½Generally, a ΔE value ≤ 3 cannot be perceived by the human eye (Wolbers 2008). Therefore, for any two samples, ΔE values at or below this range are considered acceptable matches.

Ideally, color measurements should be collected from a clean, unweathered sample area. If necessary, a scalpel is used to scrape an area clean before color matching. Due to inherent color variations in paints (especially in hand ground, pre-industrial coatings), multiple readings are taken and averaged together to establish the final CIE L*a*b* values.

Due to the deterioration, soiling, and fragmentary nature of some early paints, color readings cannot always be obtained with the Chroma Meter. In these instances, paints are matched by eye to Munsell standard color swatches and commercial paint chips, using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. Commercial systems consulted include Benjamin Moore, Sherwin Williams, Pittsburgh Paints, and the Colonial Williamsburg Color Collection.

Appendix C. Sampling memorandum

Cc: Susan Buck

Date: May 27, 2011

Re: Palmer House paint samples

On Thursday, May 26, 2011, I collected eighteen samples from original interior elements at the Palmer House (block 9, building 24, lot 27). Edward Chappell accompanied me on this sampling excursion to take field notes, examine the original woodwork and make sampling recommendations.

Staircase: Nine samples were collected from the stair, which the architectural report (Douglas 1956, 21) notes is original. It is currently painted olive-green with red-brown stringers and a black baseboard, all of which are original. The risers and treads are unpainted. On-site excavations found significant accumulations of paint, including many later white layers. These paints were very brittle and it was very difficult to obtain a complete, undisturbed stratigraphy. The earliest layers appear to be a cream or light gray on the stringers and some kind of green verdigris-containing finish on the balusters, newel posts, and handrails (large 'emerald green' particles in a dark matrix).

- 1.(PH 1) Staircase, west face of bottom stringer. 35" from floor and 68" from newel post, under the 15th baluster up from the bottom.

- 2.(PH 2) Staircase, plinth of the 15th baluster up from the bottom, north face.

- 3.(PH 3) Staircase, top of shaft of 2nd baluster up from the bottom.

- 4.(PH 4) Staircase, fascia of bottom stringer, below the 3rd baluster up from the bottom.

- 5.(PH 5) Staircase, first stair landing (there are two on the ascent to the second floor), newel post, west side, 30" up from bottom.

- 6.(PH 6) Staircase, 2nd baluster up from the newel on the second landing (on the ascent), top of the shaft, west side.

- 7.(PH 7) Staircase, top surface of newel on second floor, north face just below the handrail, 33" up from bottom.

- 8.(PH 8) Second floor bedroom, room-side of door, right (hinged) stile, 4" up from bottom, adjacent to the HL hinge.

- 9.(PH 9) Staircase, second floor landing, south face of handrail fascia, 1' out from east wall.

- 10.

(PH 10) Staircase, baseboard adjacent to window on east wall, beneath the tread of the 9th stair up from the bottom.