Cross-section Microscopy Analysis of Exterior Paints: Timson House (Block 30-1, Building 4), Williamsburg, VirginiaCross-section Microscopy Analysis Report: Timson House — Exterior Finishes (Block 30-1, Building 4)

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1755

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2013

CROSS-SECTION MICROSCOPY ANALYSIS REPORT

TIMSON HOUSE, EXTERIOR FINISHES

Block 30-1, Building 4

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION

WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA

Table of Contents

| Purpose | 3 |

| History | 3 |

| Previous Research | 5 |

| Procedures | 5 |

| Results | 6 |

| Cornice | 7 |

| Weatherboards | 17 |

| Window Frames | 24 |

| South (Front) Door Architrave and Transom | 28 |

| Binding Media Analysis | 33 |

| Pigment Identification | 37 |

| Color Matching | 39 |

| Conclusions | 42 |

| References | 44 |

| Appendix A: Sample locations | 45 |

| Appendix B: Procedures | 53 |

| Appendix C: Sampling Memorandum (2008) | 56 |

| Appendix D: Sampling Memorandum (2009) | 58 |

| Appendix E: Sampling Memorandum (2011) | 59 |

| Appendix F: FTIR Analytical Report | 61 |

Timson House, Block 30-1, Building 4, south elevation

Timson House, Block 30-1, Building 4, south elevation

| Structure: | Timson House, Block 30-1, Building 4 |

| Requested by: | Edward Chappell, Roberts Director of Architectural and Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation |

| Analyzed by: | Kirsten Travers, Graduate Fellow, Winterthur / University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation |

| Consulted: | Susan L. Buck, Ph.D., Conservator and Paint Analyst |

| Date submitted: | March 2011 |

Purpose:

The goal of this project is to use cross-section microscopy techniques to explore the early exterior finish history of the Timson House. Of particular interest is the use of paint chronologies to further understand the evolution of the building from the time of its construction to the mid-19th century.

History (Lounsbury, 2003):

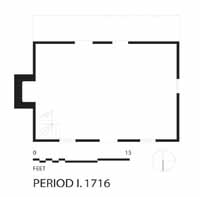

Records indicate that in 1716, Lot 323 was purchased by William Timson, a prosperous planter and justice of the peace, who constructed a dwelling on the site that same year. The date was confirmed by dendrochronology, making it one of the earliest surviving structures in Williamsburg. Originally, the building was a modest one room, one-story frame house measuring 22' 6' wide by 17' deep. At that time, the main entrance was located on the south (front) elevation between the present two windows in the central block, facing Prince George street. This is designated Period I.

South elevation, notch in the cornice, evidence of the 18th-century gable-roofed front porch

South elevation, notch in the cornice, evidence of the 18th-century gable-roofed front porch

From 1745 - 1772 (Period II), carpenter James Wray and his son, James Wray, Jr., purchased the house and used it as a rental property. Sometime during this period, a one-story shed was added to the west end of the house. The date "1752" was found inscribed on a relocated framing member during the 1937 restoration, and this is believed to be the date of the renovation.

Sometime later in Period II, a gable-roofed front porch was added to the south face of the house, over what was then the front entrance. A large notch in the fascia board of the cornice and paint ghosts along the uppermost weatherboard mark the original location of the porch.

4In the period spanning 1800-1842 (Period III), an eastern addition was constructed and the main entrance was moved from the central block to this eastern section, causing the old front door and porch to be removed and weatherboarded over. At this time, two windows were added to the north (rear) wall opposite the two south (front) windows. Greek revival architrave backbands were added around the front door and dormer windows.

Timson house sequential plans. Willie Graham, Jr. 2003.

The Period II gable-roofed front porch on the south elevation (shown in outline) was added by the author.

Alterations to the house continued from the late 19th-century into the early 20th-century. The house was purchased by the Revered W.A.R. Goodwin in the 1930s, and restoration work began several years later. During the restoration, many of the historic weatherboards were replaced, and a number of the shutters were added at that time.

In 1996, the house was the subject of a systematic investigation and emergency stabilization carried out by the CWF Architectural Research Department and Architectural Collections Management. Overall, few alterations were made to the fabric in the original section. Most of the 19th-century additions were retained as they were considered integral to the character of the house.

Previous Research:

In 1996, Susan Buck, accompanied by Willie Graham, collected fourteen samples from the Timson House. Only two of these samples were removed from the exterior, but the sample site designations were lost. One sample (13) appeared to have been removed from the trim, and did not contain a complete paint history. However, dispersed pigment samples from paints embedded in the wood fibers found white lead, red and yellow earth pigments, and vine and carbon blacks as possible components of early paints. The second sample (14) may have been removed from a weatherboard. Most paints appeared modern, but the first generation (which could not be confidently identified as 18th century) was a pale yellow paint. PLM suggests this paint is composed of white lead, yellow ochre, raw sienna and/or raw umber, and some carbon black (Buck 1999, 1).

Procedures:

On April 18, 2008, twenty-two paint samples (TI 1 — TI 22), were removed from exterior elements by Natasha Loeblich. On the Period I south (front) section of the house, samples were collected from the cornice (focusing on the notch and surrounding area), the weatherboards, and the window frames. The weatherboards on the north (rear) elevation were also sampled. A microscalpel was used to remove samples, and the locations of sample sites were recorded and photographed. All paint samples were labeled and stored in small Ziploc bags for transport, and given the prefix "TI', and numbered according to the order in which they were collected. A complete list of sample locations and photographs can be found in Appendix A.

On February 18, 2011, thirteen samples (TI 23 — TI 36), were taken from the exterior by Kirsten Travers, accompanied by Carl Lounsbury. The purpose of this second round of sampling was to collect paint evidence from the Period III addition for comparison to the known Period I section of the house.

In the laboratory, samples were examined with a stereomicroscope under low power magnification (5x to 50x), to identify those that contained the most paint evidence and would therefore be the best candidates for cross-section microscopy. Uncast sample portions were retained for future examination and analysis. The best candidates were cast in resin cubes and sanded and polished to expose the cross-section surface for microscopic examination. Please see Appendix B for sample preparation details.

The cross-section samples were examined and digitally photographed in reflected visible and ultraviolet light conditions at 20x to 400x magnifications. By comparing the resulting photomicrographs, finish generations could be interpreted based on physical characteristics such as color, texture, thickness, presence of dirt layers and extent of surface deterioration. Fluorochrome staining was also carried out on selected samples to characterize the types of binding media present (oils, carbohydrates, proteins), or to tag for the presence of Zn+2, associated with zinc white (ZnO), a pigment not available before c.1845. For more information, see Appendix B.

6Please note that the sample preparation, examination, and documentation was begun by Natasha Loeblich in 2008. In December 2010, this project was handed over to Kirsten Travers who conducted further research, additional microscopy and associated analysis, and final report writing in March 2011.

Results:

This study found surviving 18th-century exterior paints which shed light on the early construction and color history of the Timson House.

Comparative study suggests that in Period I, the cornice and weatherboards were painted red. In late Period II, after the pedimented porch was constructed over the front door, the weatherboards were painted red and the cornice was painted white. In Period III (early-19th century), when the porch was removed and the eastern addition was constructed, the entire house was coated with a tannish, waxy material and painted olive-green. The identification of the olive-green paint as a Period III color was an important benchmark in this study.

The results are organized according to architectural element — the cornice is discussed first, followed by the weatherboards, the window frames, and the entrance door transom and architrave. Natasha Loeblich collected two samples from a Timson House fragment in the CWF architectural fragments collection, but these paint stratigraphies do not correlate at all to those on the exterior of the house, and are not discussed in this report. Binding media analysis with fluorochrome stain techniques, pigment identification with polarized light microscopy (PLM), and colorimetry results are each treated in separate sections following the discussion of cross-section microscopy results.

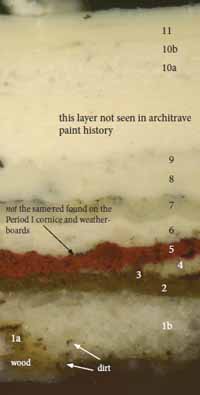

In each photomicrograph, paint stratigraphies have been annotated according to finish "generation.' For instance, a primer, paint layer, and varnish may represent one finish generation and are all given the same number, but differentiated with lowercase letters (1a, 1b, 1c, etc.). Since many samples contained redundant evidence, only the most relevant cross-section photomicrographs are presented in this report. The analytical results and pertinent observations are discussed adjacent to the photomicrographs. All results are interpreted in the conclusion, and all raw photomicrographs can be found in the appendix at the end of this report.

Cornice:

Fifteen samples were taken from the cornice on the south (front) elevation. Of these, twelve were collected from the cornice on the original, Period I section of the house (TI 1-9, TI 23-25), and for comparison, three samples were collected from the cornice on the Period III addition (TI 26-28). The earliest paints are heavily deteriorated and the evidence is fragmentary, but the results yield interesting data that informs the structural evolution of the house as well as its color history.

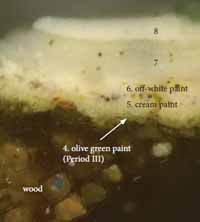

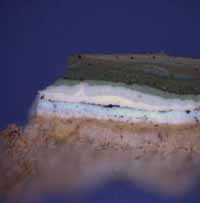

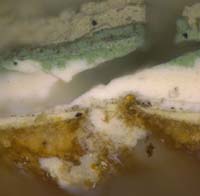

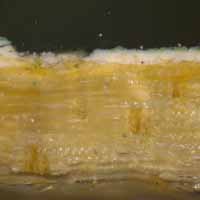

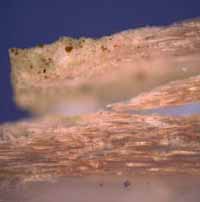

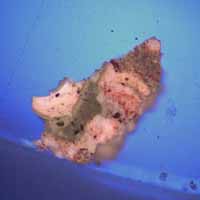

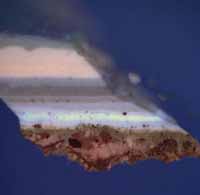

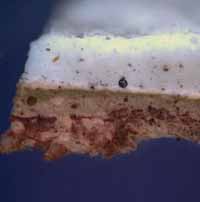

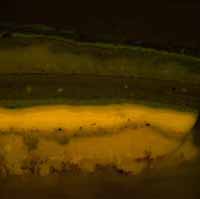

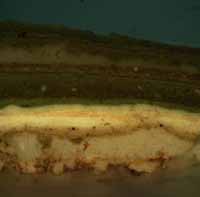

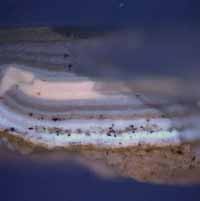

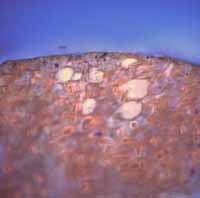

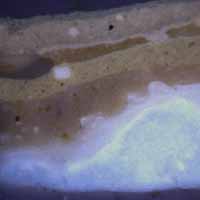

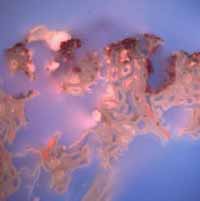

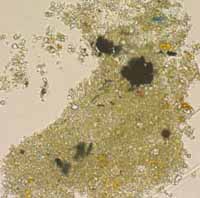

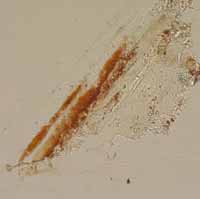

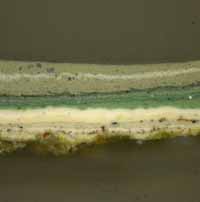

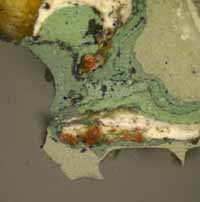

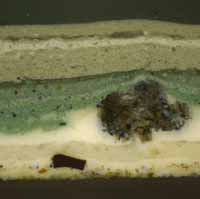

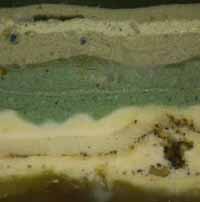

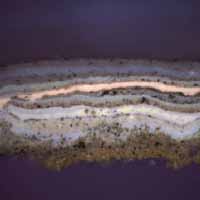

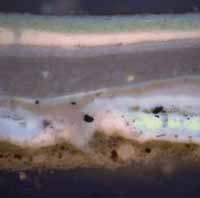

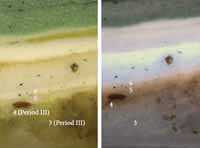

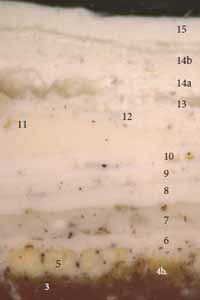

TI 6: Period I, cornice soffit

TI 6: Period I, cornice soffit

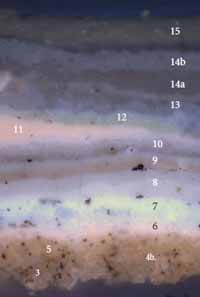

visible light (left), UV light (right), 100x

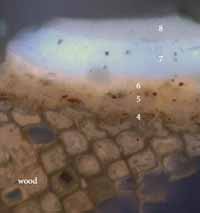

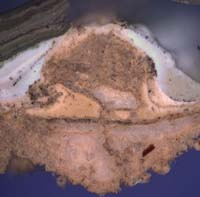

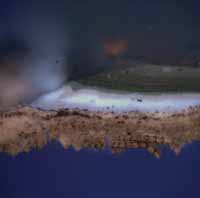

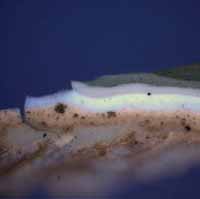

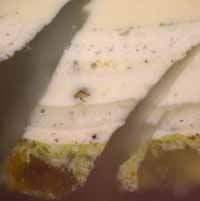

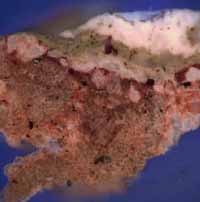

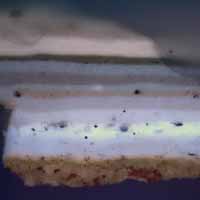

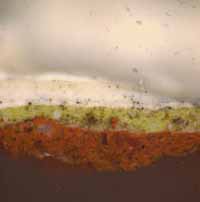

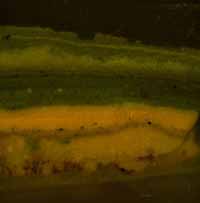

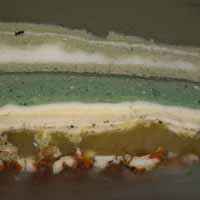

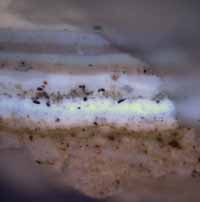

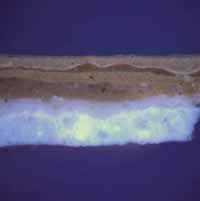

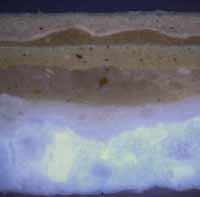

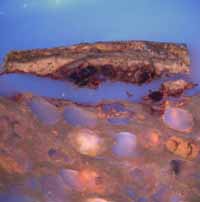

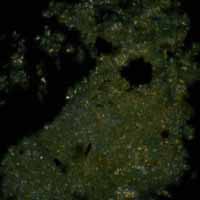

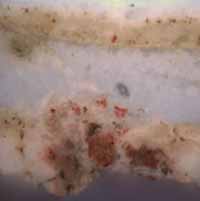

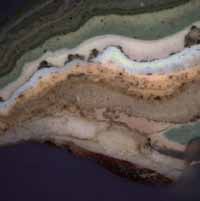

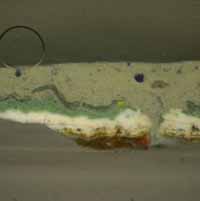

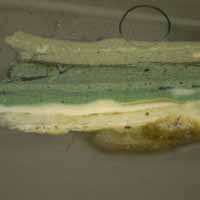

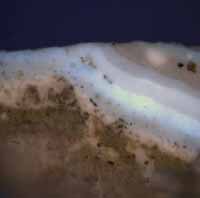

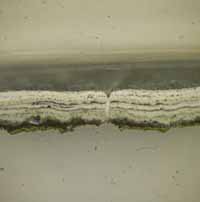

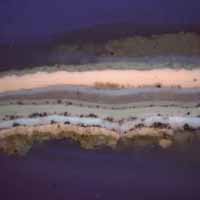

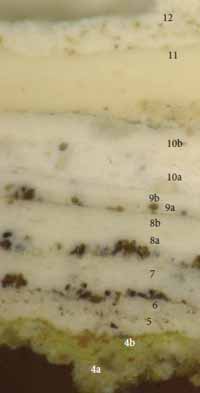

TI 27a: Period III, cornice bed mold

TI 27a: Period III, cornice bed mold

visible light (left), UV light (right), 100x

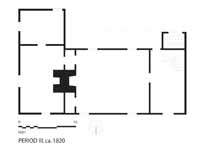

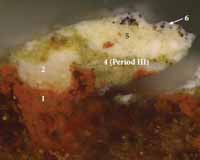

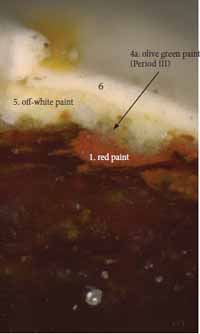

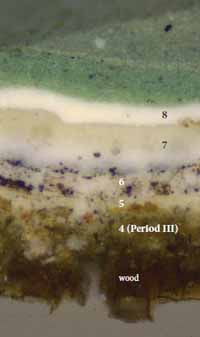

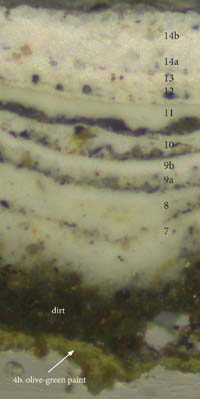

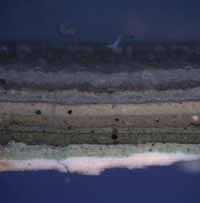

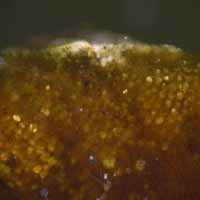

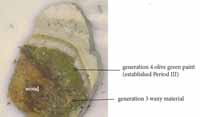

A coarsely ground red paint was found in five of the twelve Period I cornice samples (TI 6, TI 8, TI 9, TI 24, TI 25). This red paint is soiled, deteriorated and fragmented. In two of these samples (TI 6 and TI 9), the red is followed by generation 2, a white paint (see sample TI 6, above left). This layer is also heavily deteriorated. Its absence from the other samples could suggest that it weathered away in some areas. Generation 3 is a thick, tannish layer that was analyzed with FTIR (Catherine Matsen 2009, Winterthur Museum and Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory) and found to contain wax, gypsum, and chalk (see Appendix F). The purpose of this layer is unknown, but it could represent a water-resistant coating. It too, was not present in all samples. (A similar coating was found by Susan Buck on the interior of the Peyton-Randolph House (Buck 1998, 8). This was also analyzed with FTIR and found to contain wax, lead, and chalk). Generation 4 is a coarsely-ground olive-green paint with a dim autofluorescence. Generation 5 is a cream-colored paint, and generation 6 is an off-white paint.

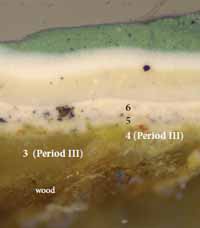

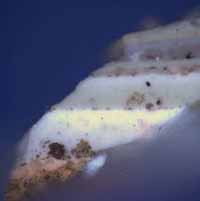

By contrast, on the Period III cornice, no early red or white paints were found (see sample TI 27a, above right). The stratigraphy begins with the tannish, waxy material identified as generation 3 on the Period I cornice (but again, this material is not present in all samples, possibly due to weathering). This is followed by generation 4, the olive-green paint with a dim autofluorescence. The rest of the stratigraphy aligns with the Period I cornice.

These comparative results are consistent with the understanding that the cornice on the central section of the house dates to the earlier period of construction. Since the eastern addition is Period III, the red and white paint generations on the central cornice must, therefore, pre-date this period.

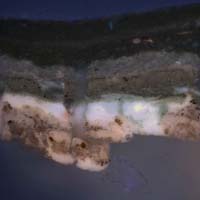

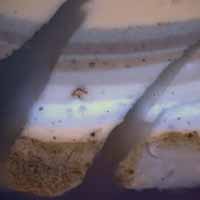

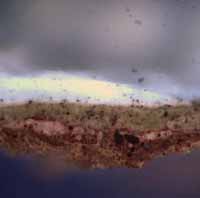

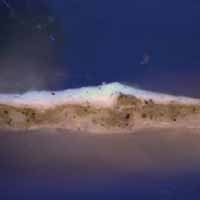

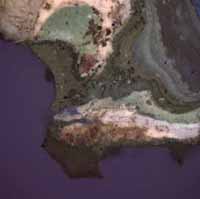

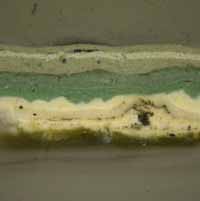

8Further comparison of the samples taken around the notch in the cornice helped clarify how these paints related to the construction history of the house. A theory put forward by Carl Lounsbury suggested that the notch was created when the cornice fascia was 'carved out' to accommodate the gabled porch believed to have been installed in Period II (Lounsbury, pers. comm., 2011). Although the paint evidence is fragmentary, the results seem to confirm that theory. For instance, in most of the samples taken away from the notch (TI 6, TI 8, TI 9), the first generation finish was the coarsely ground red-brown paint, followed by a second generation white paint, a third generation tannish material, then the fourth generation olive green paint. By contrast, in samples taken on or in the immediate vicinity of the notch which would have been subject to scraping (TI 1-5, TI 7), no red or white paints were found. Instead, the finish history begins with the tannish water-resistant coating followed by the olive green paint similar to what was found on the Period III cornice (compare sample TI 7, below left, with sample TI 27a on previous page). This is consistent with the theory that early paints were scraped away when the notch was created and the porch was installed. When the porch was removed in Period III, the notch was exposed, but then painted over when the olive-green color was applied to the entire house at that time.

In a sample taken one inch to the right of the notch there are remnants of red paint in the wood substrate that appear to have survived the scraping (see sample TI 1b, below right). This would suggest that the red paint pre-dates the porch installment, and would therefore date to Period I or early Period II.

The second generation white paint was found in two of the three samples taken away from the notch (TI 6 and TI 9). The white paint was not found in the samples taken from the notch itself (even where the red was found), or anywhere on the Period III addition. This suggests that elements of the front elevation might have been painted white after the porch was installed, in late Period II. However, the white paint evidence is so fragmentary that this theory is highly circumstantial. Furthermore, the notch in the cornice would have been adjacent to the roof shingles on the porch, which were unlikely to have been painted, and could also explain why no white paints were found adjacent to the notch (Chappell, pers. comm., March 2011).

While some questions remain as to the precise dates of the red and white paint, the evidence does support the stylistic analysis which suggests that in Period III, the central front entrance was moved to the eastern addition, leaving the notch exposed. The entire front (south) cornice was then coated with the waxy material identified as generation 3, followed by the olive-green paint identified as generation 4. This would have [remainder of paragraph is missing]

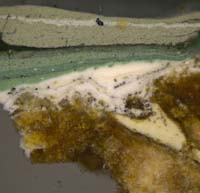

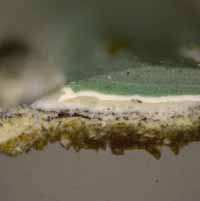

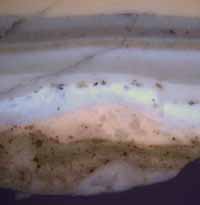

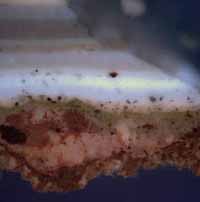

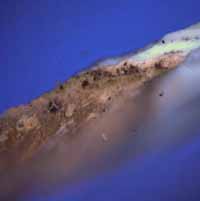

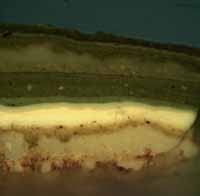

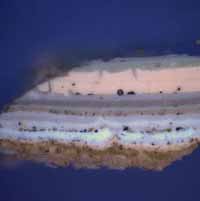

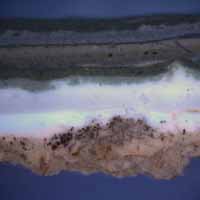

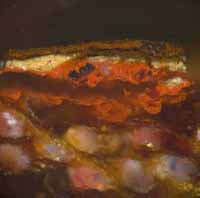

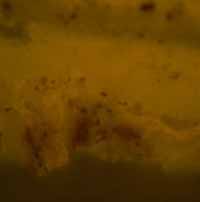

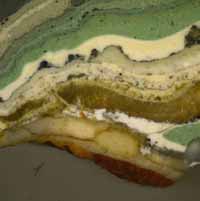

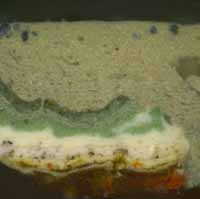

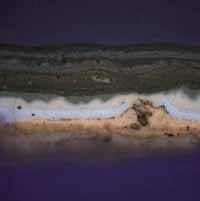

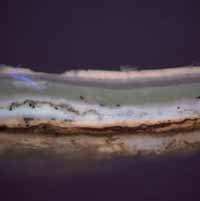

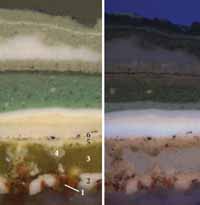

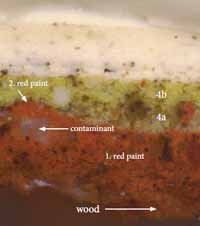

TI 7: Period I cornice, soffit behind notch

TI 7: Period I cornice, soffit behind notch

visible light (left), UV light (right), 100x

TI 1b: Period I cornice, 1' right of notch

TI 1b: Period I cornice, 1' right of notch

visible light, 100x

Sample TI 6: south elevation, Period I cornice, soffit

Sample TI 6 was taken one foot west of the notch on the Period I cornice. In this sample, the first generation is a deteriorated and fragmented red paint. The second generation is a white paint, which is also very fragmented. Generation 3 is a tannish, translucent layer that was identified as a mixture of wax, gypsum, and chalk with FTIR (see Appendix F). It does not appear to be a paint, but could be some type of water-resistant coating. Its presence as the first layer on the Period III cornice identifies this as a 19th-century material. Generation 4 is an olive-green color with a dim autofluorescence, suggestive of an oil medium. Generation 5 is a cream-colored paint that contains bright red pigment particles, and generation 6 is an off-white paint. Generations 7-17 appear to be industrially prepared paints.

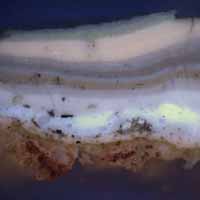

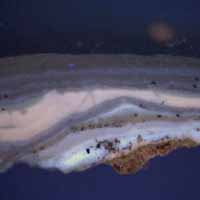

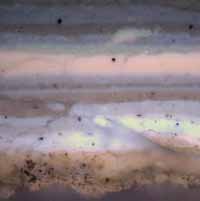

Sample TI 9: south elevation, Period I cornice, bed molding, approximately 2' east of notch

Sample TI 9 clearly shows that the red paint is the first generation applied to the Period I cornice. The second generation white paint is very fragmented in this sample, and the third generation waxy material is missing here.

The orange autofluorescence in the wood cells suggests a resinous sealant was applied before painting.

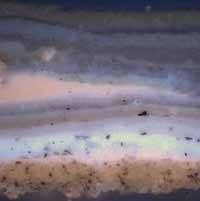

Sample TI 8: south elevation, Period I cornice, soffit, approximately 2' east of notch

Like sample TI 9 (previous page), this sample shows that the red paint was the first layer applied to the Period I cornice. The second generation white paint is missing from this sample, possibly having weathered away. The thick, waxy layer (generation 3) is also missing here.

The orange autofluorescence in the wood cells strongly suggests that a resinous sealant was used to prepare the surface before painting.

Sample TI 26a: south elevation, Period III cornice, bed mold (ovolo) above the entrance door

Sample TI 26 was taken from the Period III cornice. This sample clearly shows that the first paint applied to the cornice is the olive-green paint identified as generation 4 on the Period I cornice. The paints which follow align with those on the Period I section (all layers not shown here).

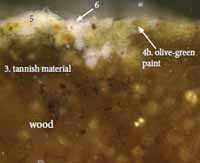

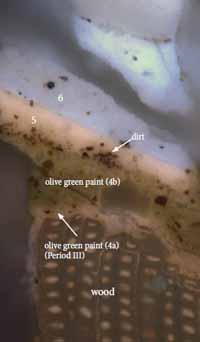

Sample TI 27a: south elevation, 19th-century cornice, bed mold (base) above the entrance door

Sample TI 27a: south elevation, 19th-century cornice, bed mold (base) above the entrance door

In this detail of sample 27a (at left), also taken from the Period III cornice, only the bottom layers are shown. Generation 3, the waxy coating, is seen here as the earliest layer. This was missing from sample TI 26a (above). This same material was also found in sample TI 28 (not shown).

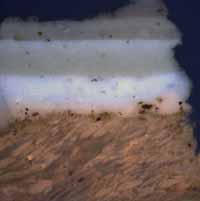

Sample TI 7: south elevation, Period I cornice, soffit behind the notch

Sample TI 7 was taken from the soffit just behind the notch in the Period I cornice. The first generation red paint and second generation white paint are not seen here, although these were found in samples collected further away from the notch. One explanation for this condition could be that these paints were lost during the installation and removal of the porch in this immediate vicinity.

The paint evidence seen here is the same as that seen on the Period III cornice, which begins with the tannish, waxy material (see sample TI 26a, previous page). This suggests that in Period III, the pedimented porch was removed, leaving the notch in the cornice exposed. It was then coated with the water-resistant waxy layer and painted an olive-green color, as was the rest of the house.

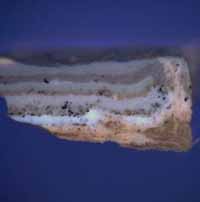

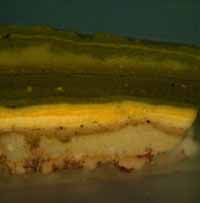

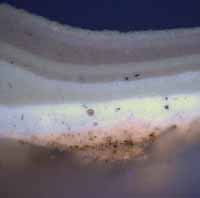

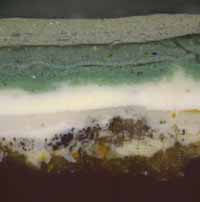

Sample TI 4: south elevation, Period I cornice, bed molding below the notch

Like sample TI 7 (shown on previous page), sample TI 4 was collected from the vicinity of the notch in the Period I cornice. The first generation red paint and second generation white paint are not seen here, possibly have been removed when the porch was installed and later taken down.

The fragmentary remnants of the olive-green paint (generation 4) are all that remain of the first paint applied to the cornice. The surface of this paint is uneven and weathered, suggesting it was exposed for a long period of time. Generation 5 is the cream-colored paint, and generation 6 is the off-white paint. Both of these generations are also covered with dirt and mold, indicating a long period of exposure before repainting. This stratigraphy is the same as that seen on the Period III cornice (see sample TI 26a, page 12), which indicates that the pedimented porch was removed and the notch was painted over at the same time the eastern addition was constructed.

Sample TI 24: south elevation, Period I cornice, metal fixture on cornice fascia, ≈12' west of notch

The paint sample removed from the edge of the metal fixture on the south cornice is shown here in its entirety. The left-hand side of the sample was attached to the metal substrate. The right-hand side of the sample was attached to the wood cornice (to which the fixture was attached). Fragmentary remnants of the first generation deep red paint were found on the cornice. However, these paints were not seen on the metal fixture. The dark red layer in this area is not paint, but results from the oxidized surface of the iron (see next page for greater detail).

Sample TI 24: south elevation, Period I cornice, metal fixture on cornice fascia, ≈12' west of notch

TI 24, visible light, 100x (layers attached to metal substrate)

TI 24, visible light, 100x (layers attached to metal substrate)

TI 24, UV light, 100x (layers attached to metal substrate)

TI 24, UV light, 100x (layers attached to metal substrate)

The rust at the bottom of this sample suggests that the iron fixture was exposed and allowed to oxidize before being coated with the third generation waxy layer. This could indicate that the metal fixture pre-dates Period III, but nothing more conclusive can be said about the date the fixture was attached to the cornice.

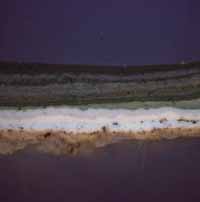

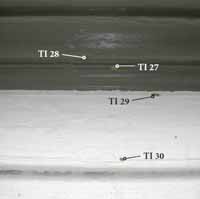

Weatherboards

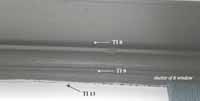

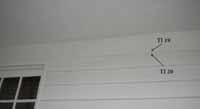

To provide a benchmark for 19th-century paints, two samples (TI 29, TI 30) were collected from the weatherboards on the front (south) elevation of the Period III addition. The results show that the first generation applied to the weatherboards is the olive-green paint. This was also the first generation applied to the cornice on this section of the house, suggesting that the entire house (trim and body) were painted olive-green after the addition was completed. Of the two samples collected, sample TI 29b contained the most intact early paint evidence, and is discussed on page 18.

On the front (south) elevation of the central, Period I section of the house, the uppermost weatherboard was observed to be wider than the others, and assumed to date from the earliest period of construction. Three out of the five samples (TI 12-14) collected from this weatherboard contained two red paint generations that pre-date the Period III olive-green paint. The two red paints appear very similar in visible light but can be distinguished more clearly in ultraviolet light. The first red paint appears to be the same as the first generation red paint found on the Period I cornice, but the deterioration of this layer makes interpretation difficult. Some inclusions of an unknown transparent material, possibly a contaminant from a dirty paintbrush, is also intermixed with these early red paints. These results are discussed on pages 19-21

With the exception of the topmost weatherboard, most boards on the central section of the house are believed to date to Period III, when the original entrance was boarded up and relocated to the eastern wing. Three samples were taken from these weatherboards (TI 15, TI 16, TI 17), and no red paint was found. In fact, the first generation is the Period III tannish waxy material, which confirms the earlier suggestion. Of all samples collected from this area, sample TI 17 had the most intact early paint evidence, and is discussed on page 22.

On the rear (north) elevation under the jetty, two samples (TI 19, TI 20) were collected from the weatherboards. These weatherboards are believed to date to Period III, contemporary with the eastern addition (Lounsbury, pers. comm., February 2011). The paint evidence confirms this theory, as the first generation is the Period III olive green paint. Of the two samples collected, sample TI 20 contained the most intact early paint evidence, and is discussed on page 23.

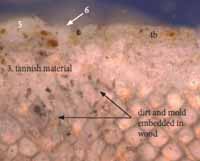

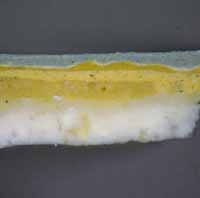

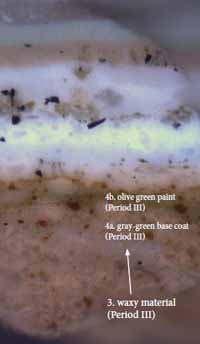

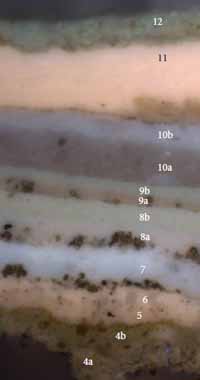

Sample 29: South elevation, Period III eastern addition, top edge of uppermost weatherboard, above the entrance door.

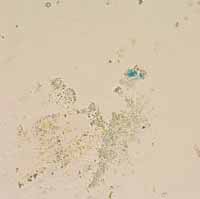

TI 29b, visible light. 200x (only early layers shown)

TI 29b, visible light. 200x (only early layers shown)

TI 29b, UV light. 200x (only early layers shown)

TI 29b, UV light. 200x (only early layers shown)

The weatherboard from which sample TI 29b was taken dates to Period III.

The sample clearly shows that the olive-green paint was the first generation applied to the weatherboards on the eastern addition. This generation consists of a thin green base coat (4a) and a coarsely ground olive-green paint that contains yellow, white, red, and green pigment particles (4b). The dirt and mold on the surface of this layer suggests it was exposed for a long period of time.

This sample was used as a benchmark from which to compare the paint histories of other weatherboard samples from the house.

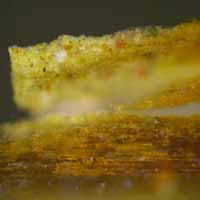

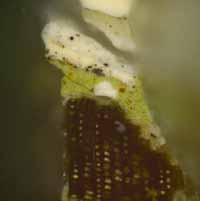

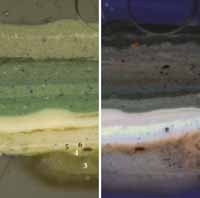

Sample TI 13, south elevation, Period I weatherboard, top edge of uppermost wide board

Discussed on next page.

Sample TI 12a, south elevation, Period I weatherboard, uppermost wide board in bottom bead, approximately 2' east of notch (just below sample TI 13).

Samples TI 12a and TI 13 (previous page) were both taken from the same Period I weatherboard. In both samples, the first generation red paint appears to be the same as the first generation red paint found on the Period I cornice. This could suggest that early in the history of the house, both the trim and the body were painted red.

However, the second generation white paint that was found on the cornice is not seen here. Instead, there is a second red paint generation (this generation is more apparent in sample TI 13). This would suggest that in the second generation, the weatherboards were painted red and the cornice was painted white. This color scheme may date to Period II, when the gabled porch was constructed.

In both samples, inclusions of what appears to be the wax-based putty (generation 3) is intermixed with the early red paints, but its fragmentary condition makes interpretation difficult.

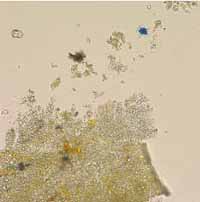

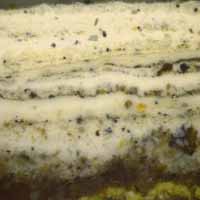

Sample TI 14, south elevation, Period I weatherboard, uppermost wide board in bottom bead, approximately 2 ½' east of notch (≈6' to the right of sample TI 12).

TI 14, visible light, 200x (only early layers shown)

TI 14, visible light, 200x (only early layers shown)

TI 14, UV light, 200x (only early layers shown)

TI 14, UV light, 200x (only early layers shown)

Again, this sample from a Period I weatherboard shows approximately two red paint generations that have been applied before Period III. The first red paint generation contains a greater proportion of darker pigment particles, and has a much darker autofluorescence that the second red paint generation. Both are coarsely ground, suggestive of a hand-prepared paint.

The whitish/transparent inclusions between the two red paints do not strongly compare with the generation 2 white paint found on the cornice (which is a bright, opaque white in visible light), or the third generation waxy-material found throughout the house (which is light brown in visible light). This analysis was not able to identify them with confidence, but it is possible that these are contaminants from a dirty paintbrush.

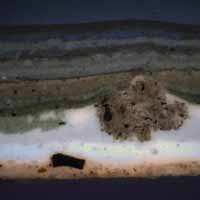

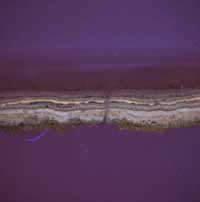

Sample 17: South elevation, top edge of the 4th weatherboard from the top, below the notch.

TI 17, visible light, 200x (only early layers shown)

TI 17, visible light, 200x (only early layers shown)

TI 17, UV light, 200x (only early layers shown)

TI 17, UV light, 200x (only early layers shown)

Sample 17 was taken from what was thought to be Period III weatherboard. The paint evidence supports that theory.

The earliest paint generation is the tannish, waxy material that dates to Period III. Again, this material does not appear to be a paint but rather some type of water-resistant coating. It is followed by a gray-green base coat and an olive-green finish color, which also dates to Period III. It appears that the entire house was painted olive-green at that time.

Sample TI 20: North elevation (under the jetty), stop edge of second board from top.

TI 20, visible light (3), 200x (only early layers shown)

TI 20, visible light (3), 200x (only early layers shown)

TI 20, UV light (3), 200x (only early layers shown)

TI 20, UV light (3), 200x (only early layers shown)

The first paint generation on the northern (rear) weatherboards is the Period III olive-green paint that is the same first generation paint used on the Period III eastern addition, suggesting that they are contemporary. The waxy material (generation 3) and gray-green primer (generation 4a), are missing from this sample.

Window Frames

Three samples were collected from the window frames. The earliest paints appear to date from Period III.

On the south (front) elevation, sample TI 18 was taken from the far east window. This section of the house is Period I, but the date of the frame was uncertain. No early red or white paints were found. Instead, the paint stratigraphy begins with a tannish water-resistant coating and the olive-green paint that dates to Period III. There is some dirt embedded deep in the wood cells that could suggest that the wood was already extensively weathered when the tannish material was applied, but the absence of any 18th-century paints could also indicate that this frame is not original. This sample is shown and discussed on page 25.

Sample TI 35 was also taken from the south (front) elevation of the house, from the far west window on the shed addition that was constructed in Period II. This window was observed to have a beaded frame that was not seen elsewhere (Lounsbury, pers. comm., February 2011), and it was hoped that the paint evidence would elucidate its history. However, as with the east window, the paint stratigraphy begins with the Period III olive-green paint. Considering this paint evidence, the window frame on the shed addition probably dates to Period III, when the corner chimney was taken down and the original chimney was rebuilt (Lounsbury, personal comment, April 2011). This sample is shown and discussed on page 26.

Sample TI 36 was taken from the north (rear) elevation of the house, from the west window under the jetty. This section of the house is original but was altered at an unknown date, possibly the 19th century (Lounsbury, pers. comm., 2011). The resulting paint history was different from that observed on the south (front) of the house. Here, only industrially-prepared paints were found, which appear to post-date Period III. This sample is shown and discussed on page 27.

Sample 18: South elevation, Period I, easternmost window, top of frame on left side.

For further discussion of window frame paints, see next page.

TI 18, visible light (3), 200x

TI 18, visible light (3), 200x

Sample 35: South elevation, far west window, Period II, western edge of left frame.

TI 35, visible light, 200x (later layers not shown)

TI 35, visible light, 200x (later layers not shown)

TI 35, UV light, 200x (later layers not shown)

TI 35, UV light, 200x (later layers not shown)

Examination of the uncast portion of sample TI 35 indicates that the complete paint history is present. The stratigraphy begins with the coarsely-ground olive-green paint that dates to Period III. This paint history is the same as sample TI 18, removed from the frame of the easternmost window on the same elevation (see previous page). Most importantly, both of these samples have the same early paint history as the front door architrave on the Period III addition (see pages 29-30).

The existence of the same paint histories starting with the Period III olive-green paint on the far west (TI 35), and easternmost window frames (TI 18), suggests that these frames were later additions. In fact, after reviewing the paint evidence, Carl Lounsbury noted that the far west window could date to Period III, when the corner chimney was removed and the original chimney was rebuilt (Lounsbury, personal comment, April 2011).

Sample 36: North elevation, far west window under jetty, inner edge of right frame, 2' up from bottom sill.

In sample TI 36, approximately thirteen paint generations were identified, and none appear to date from the 18th century. However, generations 1 and 2 are distinctly different from the early paints found on the south elevation window frames (pages 25-26). A tannish material (1a), was first applied to the substrate (substrate not shown). This material has a pinkish autofluorescence which distinguishes it from the waxy material with the bluish-autofluorescence found throughout the south elevation. This is followed by a white paint (1b), that contains bright autofluorescent particles suggestive of zinc white (ZnO), a pigment that was not introduced before c.1845, which post-dates Period III. There is no dirt or distinct boundary which separates the tannish material from the zinc white paint, suggesting that both were applied at the same time. This generation aligns with generation 1 on the transom (see pages 31-32). Generation 2 is a dark gray paint that was not seen elsewhere on the house.

Generations 5-15 align with the paint evidence on the south elevation window frames.

Since the early paint history here is clearly different from the frames on the south (front) elevation, this suggests that this particular window frame was re-used from another building.

South (front) Door Architrave and Transom

Four samples were collected from the door architrave and transom (TI 31 — TI 34). These elements are known to date to Period III, and were taken for comparison to the earlier sections of the house. It was also hoped that these samples would determine whether the transom was installed at the same time as the architrave, or later.

The sample removed from the top surface of the architrave (TI 31) clearly shows that the Period III olive-green paint is the first generation. This is consistent with this door as a Period III element. This was corroborated by architrave sample TI 34, which also began with the olive-green paint.

The paint history of the transom is very different from the architrave, and all of the paints appear to have been industrially prepared. A tannish material is the earliest layer applied to this element, although its pinkish autofluorescence distinguishes it from the Period III waxy material seen in so many other areas on the house. This is followed by a white paint that appears to contain zinc white, suggested by 'twinkling' autofluorescent particles within its matrix. This pigment was not commercially available before c.1845, suggesting that the transom is a later addition. In fact, during this investigation the author was informed that the earliest photographs of the house do not show the transom in place (Lounsbury, personal comment, April 2011). Interestingly, its early stratigraphy is very similar to that found on the window architrave on the north elevation. Since these early paints do not align with anything else on the house, it is possible that the transom and northern window frame are re-used from another building.

Sample 31: South elevation, Period III, front door architrave, top surface.

Although the substrate is not shown, the impression of wood fibers was seen on the bottom of the uncast portion of this sample, indicating that the complete paint history is present. The first paint applied to the architrave is the olive-green paint that dates to Period III. There is a very thick layer of dirt on the surface of this paint, resulting from the horizontal orientation of the sample location. Generations 5 and 6 are missing, but may have worn away or might not have been applied since the top of the architrave is generally not visible at eye level, and may not have been repainted as frequently. Generations 7-14 align with the window frames, suggesting that all exterior trim received the same decorative treatment over time.

Sample 34: South elevation, Period III, front door architrave, east edge of left side

This sample further corroborates what was seen in sample 31: that the first generation applied to the front (south) door architrave is the Period III olive-green paint. Here, the green base coat (4a) is seen below the olive-green finish coat (4b). This base coat was absent from sample TI 31 (see previous page), but could result from the extensive deterioration of the paints in that particular location. Generations 5-12 all appear to be industrially prepared white and off-white paints.

It should be noted that this stratigraphy is almost identical to sample TI 35, taken from the westernmost window frame on the south elevation Period II shed addition (see page 26). This suggests that the window frame may belong to Period III, or that its earliest paints have weathered away.

Sample 32: South elevation, Period III, front door transom, inner (west-facing) edge of right frame.

For further discussion of transom paints, see next page.

The tannish material applied to the wood substrate has a pinkish autofluorescence. This is very different from the tannish material found elsewhere throughout the house (compare to sample TI 6, generation 3, page 9).

Sample 33: South elevation, Period III, front door transom, sash, furthest right stile, bottom right.

The results show that the early paint history on the south (front) door transom does not align with the architrave (see pages 29-30). A tannish material has been applied to the wood (this is more visible in transom sample TI 32 (previous page), but it does not appear to be the same Period III tannish material found throughout the house. This is followed by a white paint that contains bright twinkling autofluorescent particles suggestive of zinc white (ZnO). The presence of this pigment suggests the earliest paint post-dates c.1845, indicating the transom was added after Period III. Generation 2 is a brown paint, followed by a white paint (generation 4), and a deep red paint (generation 5), which is not the same as the first generation red paint found on the cornice and weatherboards. This early paint history does not align with any other samples seen in this study, and may suggest that the transom was re-used from another structure. It might have been installed around generation 6, when the paint stratigraphy aligns with that seen on the architrave.

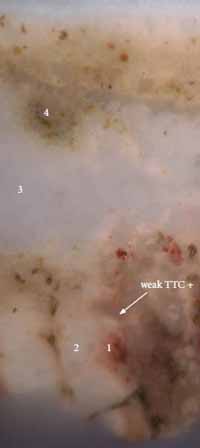

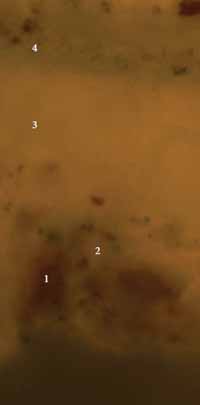

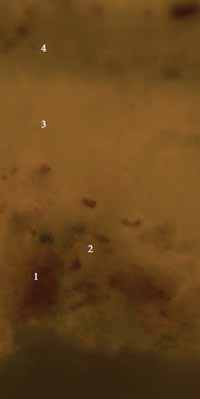

Binding media analysis results — Carbohydrates

Sample TI 6: south (front) elevation, Period I cornice, soffit

TI 6, UV light, 400x (early layers only)

TI 6, UV light, 400x (early layers only)

Before TTC stain for carbohydrates

TI 6, UV light, 400x (early layers only)

TI 6, UV light, 400x (early layers only)

After TTC stain

Sample TI 6 was stained with TTC to determine the presence of carbohydrates in the earliest paints. Only a very minor reaction (a dark red-brown color) was observed around the disrupted boundary between generations 1 and 2. The deterioration of this layer and the weakness of the reaction makes it difficult to interpret these results meaningfully.

34 TI 6, B-2A filter, 400x (early layers only)

TI 6, B-2A filter, 400x (early layers only)

Before FITC stain for proteins

TI 6, B-2A filter, 400x (early layers only)

TI 6, B-2A filter, 400x (early layers only)

After FITC stain

Generations 1-4 in sample TI 6 were stained with FITC to determine the presence of proteins in the earliest paints. No reactions (a bright yellow fluorescence) were observed.

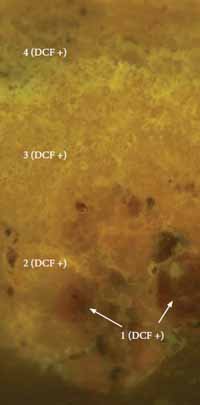

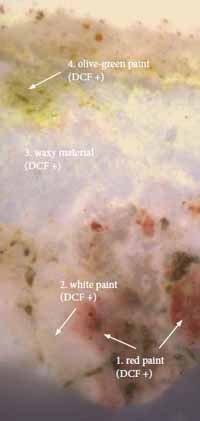

35 TI 6, B-2A filter, 400x

TI 6, B-2A filter, 400x

Before DCF stain

TI 6, B-2A filter, 400x

TI 6, B-2A filter, 400x

After DCF stain for lipids (oils)

Generations 1-4 in sample TI 6 were stained with DCF to determine the presence of lipids (oils) in the earliest paints. The sample target area is shown in visible light (see inset). A positive reaction (bright yellow-green fluorescence) was observed in all layers. This reaction was also observed in UV light (see next page), where the reaction was weaker but the typical color was yellow, indicating the presence of saturated lipids, while generation 3 also exhibited a pink reaction for unsaturated lipids.

36 TI 6, UV light, 400x (early layers only)

TI 6, UV light, 400x (early layers only)

Before DCF stain for lipids (oils)

TI 6, UV light, 400x

TI 6, UV light, 400x

After DCF stain

Generations 1-4 in sample TI 6 were stained with DCF to determine the presence of lipids (oils) in the earliest paints, and viewed in UV light to determine the nature of the reaction. The results suggest that all layers are oil-bound. A positive reaction for saturated lipids (bright yellow-green fluorescence) was observed in all layers. A minor pinkish reaction for unsaturated lipids was observed in generation 3. This reaction was more readily observed under the B-2A filter (previous page).

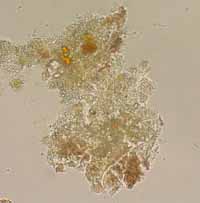

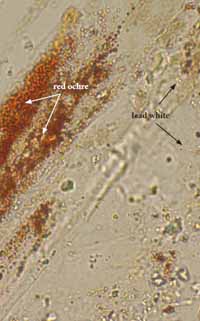

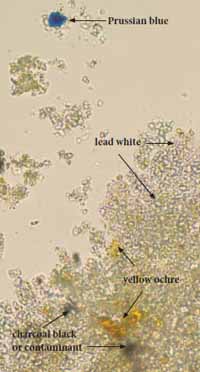

37 TI 6, dispersed pigments from first generation red paint

TI 6, dispersed pigments from first generation red paint

Transmitted cross polarized light, 1000x

TI 6, dispersed pigments from first generation red paint

TI 6, dispersed pigments from first generation red paint

Transmitted cross polarized light, 1000x

A sample of the red paint layer (generation 1), was collected with a clean scalpel blade from the uncast portion of TI 6, dispersed on a glass slide, and mounted with Cargille Meltmount (refractive index 1.66) for polarized light microscopy.

Agglomerations of small red particles were observed. These particles were red-orange in plane polarized transmitted light and isotropic (dark) when viewed in cross polarized light, suggestive of an iron earth pigment (Fe2O3), such as red ochre. Accessory phases of various clay minerals such as quartz, kaolinite, and feldspars were also present. These minerals are often associated with earth pigments (Eastaugh et. al. 2008, 903).

A few particles of lead white were also seen. (2PbCO3 ‧ Pb(OH)2), consisting of small, rounded particles that are colorless or pale green in transmitted light and birefringent (bright) under crossed polars. It is possible that these particles belong to the second generation white paint, and may have been collected accidentally.

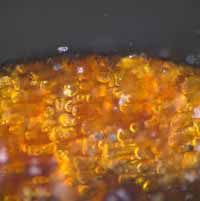

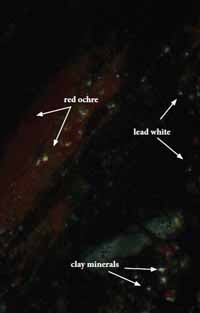

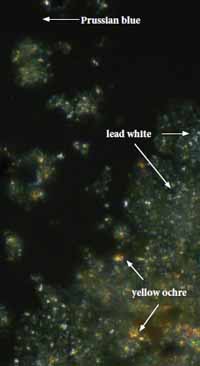

38 TI 6, dispersed pigments from fourth generation green paint. Transmitted plane polarized light, 1000x

TI 6, dispersed pigments from fourth generation green paint. Transmitted plane polarized light, 1000x

TI 6, dispersed pigments from fourth generation green paint. Transmitted cross polarized light, 1000x

TI 6, dispersed pigments from fourth generation green paint. Transmitted cross polarized light, 1000x

A sample of the olive-green paint layer (generation 4), was collected with a clean scalpel blade from the uncast portion of TI 6, dispersed on a glass slide, and mounted with Cargille Meltmount (refractive index 1.66) for polarized light microscopy.

The majority of sample appears to contain lead white (2PbCO3 ‧ Pb(OH)2), consisting of small, rounded particles that are colorless or green in transmitted light and birefringent (bright) under crossed polars. Some isotropic earth pigments, most likely yellow ochre (Fe2O3 ‧ nH2O), were also observed. A smaller amount of Prussian blue (Fe4[Fe(CN)6]3) pigment was also present, distinguishable as a deep blue particles in transmitted light (sometimes displaying a 'smeary' quality), that were completely isotropic (dark) under crossed polars. Some amorphous isotropic black particles were also present. Due to the deterioration of this paint, it was impossible to determine whether these particles resulted from dirt embedded in the paint, or a black pigment (such as carbon black), deliberately added to the paint. However, considering the 'olive-green' color of this paint, it seems likely that the black pigmentation was deliberate.

Color Matching

Sample TI 6: south (front) elevation, Period I cornice, soffit

TI 6, underside of uncast paint sample showing earliest paints, visible light, 40x. Note the disruption of the early paints.

TI 6, underside of uncast paint sample showing earliest paints, visible light, 40x. Note the disruption of the early paints.

The surviving remnants of deep red and white paint in the samples from the Timson House were too small and deteriorated to be measured within the 0.3mm measurement limit of the colorimeter/microscope. Instead, the closest match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source to swatches from both the standard Munsell color system and the Benjamin Moore Color Preview set. The level of gloss could not be determined. The results are listed below:

| closest Munsell match | Benjamin Moore color swatch | |

|---|---|---|

| Generation 1: deep red paint | 10R 3/6 | EXT. RM "Country Redwood' |

| Generation 2: white paint | 10 PB 9/1 | INT. RM "Super white' |

Sample TI 29: South elevation, Period III eastern addition, top edge of uppermost weatherboard

TI 29, underside of uncast paint sample showing wood substrate and olive-green paint, visible light, 40x.

TI 29, underside of uncast paint sample showing wood substrate and olive-green paint, visible light, 40x.

The Period III olive green paint from sample TI 29 was measured with a Minolta Chroma Meter colorimeter/ microscope to obtain color values in CIE L*a*b* and Munsell colorspace. Readings were obtained from two different areas measuring 0.3 mm across, and averaged together resulting in one value (although the difference between the two readings was negligible).

| Period III olive-green paint | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| area 1 | 51.82 | -4.96 | +19.39 |

| area 2 | 51.35 | -5.13 | +19.39 |

| average | 51.59 | -5.05 | +19.39 |

The Munsell values were also very similar:

| Period III olive-green paint | hue | value | chroma |

|---|---|---|---|

| area 1 | 9.0Y | 5.1 | 2.7 |

| area 2 | 9.2Y | 5.1 | 2.7 |

The closest commercial match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. Commercial swatches used for matching included Benjamin Moore, Sherwin Williams, Pittsburgh Paints, and the Colonial Williamsburg Color Collection. Final determination of the closest match was carried out by obtaining the CIE L*a*b* value of the commercial swatch, and mathematically calculating the color difference (known as ΔE), between the swatch and the actual Timson house olive-green paint. The commercial swatch with the lowest ΔE was the best match (see Appendix B for more details).

41The closest commercial color match was determined to be Sherwin Williams Exterior Coloranswers Collection swatch #SW 2369, named 'Olive Grove'. The color difference (ΔE) between this swatch and the Timson house olive green paint was calculated as 2.29. Since the average human eye cannot detect ΔE values less than 3, this commercial swatch is an excellent visual match.

Conclusions

This paint study found significant evidence which elucidates the early construction and color history of the Timson house.

The results suggest that in Period I, the cornice and weatherboards were painted a deep red color. This deep red paint was composed of red earth pigments in a drying oil. The closest Munsell and commercial match for the deep red paint is provided on page 39.

In late Period II, after the gable-roofed porch was constructed over the front door, the weatherboards may have been painted red while the cornice was painted white. This white paint was oil-bound and was most likely prepared with lead white pigment. No other colored pigments were observed. The closest Munsell and commercial match for the second generation white paint is provided on page 39.

In Period III (19th century), when the eastern addition was constructed, the entire house was coated with a tannish, waxy material and painted olive-green. This analysis was not able to determine the purpose of the tannish, waxy coating, but it is most likely a water-proofing agent applied to the exterior of the house. The olive-green paint was oil-bound and contained lead white, yellow ochre, Prussian blue, and possibly carbon black pigments. The identification of the olive-green paint as a Period III color was an important benchmark for the 19th century in this study. The closest Munsell and commercial color match for this olive-green paint is provided on pages 40-41.

Cornice: Sampling concentrated around the notch in the cornice that was believed to be a 'scar' from the Period II gable-roofed front porch. The results found the first generation red paint and second generation white paints away from the notch. By contrast, on or in the immediate vicinity of the notch, the Period III olive-green paint was the first generation, although in one sample, remnants of red paints were embedded in the wood substrate. These findings support the theory that in Period I or early Period II, the cornice was painted a deep red color. Sometime later, the cornice fascia was carved away to accommodate the porch, which may have pushed some of the red paints deep into the wood fibers, but in most areas the red paint was removed completely. Once the porch was completed, the entire cornice was painted white, possibly to match the porch. In Period III, the porch was removed, exposing the notch. The front door was moved to the eastern addition, and the entire cornice was painted olive-green, as was the rest of the house.

Weatherboards: This study confirmed that the uppermost weatherboard on the central south (front) elevation is an early element, possibly Period I. The paint evidence on this weatherboard sheds light on early finishes. Comparison to the cornice suggests that in the first generation, the weatherboards were painted with the same deep red as the cornice. In the second generation, the weatherboards were painted red again, while the cornice (and possibly the gabled porch) was painted white. In the third generation (Period III), some of the weatherboards were coated with the tannish waxy material and all were painted olive-green.

The wax with olive-green paint was the earliest finish found on the lower weatherboards on the central south (front) section, the eastern addition, and the north elevation under the jetty, suggesting that all of these boards were installed in Period III.

43Window frames: No 18th-century paints were found on the window frames. On the south (front) elevation, the paint history of the two window frames sampled begins with the Period III olive-green paint. The paint history of the window frame on the north (rear) elevation does not compare to the frames on the south elevation. In fact, this frame appears to contain only industrially prepared paints. These findings suggest that suggesting that the window frames are later additions or that their early paint histories are lost.

Door architrave and transom: The two samples collected from the door architrave show that the earliest generation is the Period III olive-green paint. This is consistent with the knowledge that the entrance is a Period III addition. However, the two samples from the transom contain early paints that do not align with the architrave. In fact, the transom appears to contain only industrially prepared paints. Furthermore, as this investigation progressed, it was learned that the earliest photographs of the house do not show the transom in place (Lounsbury, personal comment, April 2011). These findings suggest that the transom is a later addition, one that could have been re-used from another building.

References

- Buck, S. December 1998. Peyton Randolph House Phase II — Addendum. Unpublished report prepared for the Architectural Research Department, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Buck, S. August 1999. Cross-section microscopy report: the Timson House, Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia. Unpublished report prepared for the Architectural Research Department, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Eastaugh, N., et. al. 2008. Pigment Compendium: a dictionary and optical microscopy of historical pigments. Oxford, Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Gettens, R., and G. Stout. 1942. Painting materials: a short encyclopedia. New York, Dover Publications, Inc.

- Lounsbury, C., October 2003. An architectural summary of the Timson House, block 30-1, building 4, Williamsburg, Virginia. Architectural Research Department, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Matsen, C. March 2009. Timson House: analytical report. Unpublished report prepared for the Architectural Research Department, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Appendix A. Samples and Sample Locations

| Sample number | Sample locations | Taken by/date |

|---|---|---|

| TI 1 | South elevation cornice, on board with cutout notch, 1' right of end of notch, top edge of front face | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 2 | Same as TI 1, right side of north edge of notch, ½' from bottom edge, on narrow face of board | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 3 | Same as TI 1, 1' left of end of notch, rear side of board | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 4 | South elevation cornice, bed mold, in bead below ovolo, below notch Loeblich | April 2008 |

| TI 5 | South elevation cornice, crown mold, in bead on lower edge, above left side of notch | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 6 | South elevation cornice, soffit, front edge, 1' from left end of notch | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 7 | South elevation cornice, soffit, rear edge, below notch | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 8 | South elevation cornice, soffit, back edge, 2' from left edge of right window | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 9 | South elevation cornice, bed mold, in bead below ovolo, 2' left of right window | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 10 | South elevation weatherboard, uppermost wide board, top edge, below notch | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 11 | South elevation weatherboard, uppermost wide board, in bottom bead, below notch | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 12 | South elevation weatherboard, uppermost wide board, in bottom bead, 1' right of ghost of raking door pediment | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 13 | South elevation weatherboard, uppermost wide board, top edge, 1' left of open left shutter of right window | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 14 | South elevation weatherboard, uppermost wide board, in bottom bead, ½' from right window, behind left shutter | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 15 | South elevation weatherboard, 2nd board down from top, top edge, ½' from right window, behind left shutter | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 16 | South elevation weatherboard, 2nd board down from top, top edge, below notch | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 17 | South elevation weatherboard, 4th board down from top, top edge, below notch | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 18 | South elevation, right window, top of frame on left side, 1' left of shutter hinge near top of 2nd weatherboard down | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 19 | North elevation weatherboard, uppermost wide board, in bottom bead, about 5' from east wing | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 20 | North elevation weatherboard, 2nd board down from top, top edge, about 5' from east wing | Loeblich April 2008 |

| TI 21 | Fragment TMH016-07, backband or strip of wood, middle length piece, dark coating on back edge, 9' from cut end, in center of unpainted side | Loeblich Feb. 2009 |

| 46 | ||

| TI 22 | Fragment TMH016-07, backband or strip of wood, longest piece, 5 ½' from cut end at back edge, may have plaster ghost | Loeblich Feb. 2009 |

| TI 23 | South elevation, left side of the notch in the cornice | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 24 | South elevation, cornice, bottom edge of metal fixture attached to fascia, left of notch | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 25 | South elevation, cornice, backside (north) of bottom lip of fascia, just behind the metal fixture attached to fascia | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 26 | South elevation, eastern addition (19th c.), top of cornice bed molding, above entrance door | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 27 | South elevation, eastern addition (19th c.), base of cornice bed molding, above entrance door | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 28 | South elevation, eastern addition (19th c.), cornice soffit above entrance door | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 29 | South elevation, eastern addition (19th c.), uppermost weatherboard, top edge, above entrance door | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 30 | South elevation, eastern addition (19th c.), uppermost weatherboard, in bottom bead | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 31 | South elevation, eastern addition (19th c.), top sill of entrance door architrave | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 32 | South elevation, eastern addition (19th c.), transom, right frame inner (western) edge | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 33 | South elevation, eastern addition (19th c.), transom sash, far right stile, bottom right | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 34 | South elevation, eastern addition (19th c.), entrance door architrave, east-facing edge | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 35 | South elevation, western shed addition (mid-18th c.), window frame, western edge, 16' from bottom | Travers Feb. 2011 |

| TI 36 | North elevation, westernmost window under jetty. Architrave, right side of frame, inner edge approx. 2' up from sill | Travers Feb. 2011 |

South elevation, cornice, Period I section of house, between 2nd and 3rd window from the west

South elevation, cornice, Period I section of house, between 2nd and 3rd window from the west

South elevation, cornice, looking straight up from ground. Period I section of house, between 2nd and 3rd window from the west

South elevation, cornice, looking straight up from ground. Period I section of house, between 2nd and 3rd window from the west

South elevation, cornice, Period I section of house, between 2nd and 3rd window from the west

South elevation, cornice, Period I section of house, between 2nd and 3rd window from the west

South elevation, cornice, Period I section of house, between 2nd and 3rd window from the west

South elevation, cornice, Period I section of house, between 2nd and 3rd window from the west

South elevation, cornice, Period I section of house, between 2nd and 3rd window from the west

South elevation, cornice, Period I section of house, between 2nd and 3rd window from the west

North elevation, between two windows, of Period I section of house.

North elevation, between two windows, of Period I section of house.

There are no photographs of samples TI 21 -22 (architectural fragments).

No photograph of TI 25 (underside of south cornice fascia)

51 South elevation, eastern addition above front entrance

South elevation, eastern addition above front entrance

South elevation, eastern addition, front entrance door architrave top surface

South elevation, eastern addition, front entrance door architrave top surface

South elevation, eastern addition, transom above front entrance door

South elevation, eastern addition, transom above front entrance door

South elevation, eastern addition, entrance door architrave

South elevation, eastern addition, entrance door architrave

Appendix B: Procedures

Sample Preparation:

The samples were cast in mini-cubes of Extec Polyester Clear Resin (methyl methacrylate monomer), polymerized with the recommended amount of methyl ethyl ketone peroxide catalyst. The resin was allowed to cure for 24 hours under ambient light. After cure, the individual cubes were removed from the casting tray and sanded down using a rotary sander with grits ranging from 200 - 600 to expose the cross-section surface. The samples were then dry polished with silica-embedded Micro-mesh Inc. cloths with grits ranging from 1500 to 12,000, lending the final cross-section surface a glassy-smooth finish.

Microscopy and Documentation:

The cross-section samples were examined using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope equipped with an EXFO X-cite 120 fluorescence illumination system fiberoptic halogen light source. Samples were examined and photographed under visible and ultraviolet light conditions (380-330 nm), at 20 to 200x magnifications. Digital images were captured using a Spot Flex digital camera with Spot Advance (version 4.6) software. All images were recorded as 12.6 MB tiff files and stored on a hard drive in a folder titled "Timson' on Susan Buck's laboratory computer. A separate set of images will be stored on the CWF digital database, accompanied by a digital version of the final report.

Information Provided by Visible and Ultraviolet Light Microscopy:

When examining paint cross-sections under reflected visible and ultraviolet light conditions, a number of physical characteristics can be observed to assist with the interpretation of a paint stratigraphy. These include the number and color of layers applied to a substrate, the thickness or surface texture of layers, and pigment particle size and distribution within the paint film. Relative time periods for coatings can sometimes be assigned at this stage: for instance, pre-industrial-era paints were hand ground, lending them a coarse, uneven surface texture with large pigment particles that vary in size and shape. By contrast, more "modern', industrially-prepared paints have smoother, even surfaces and machine-ground pigment particles of a consistent size and shape. Furthermore, he presence of cracks, dirt layers, or biological growth between layers can indicate presentation surfaces and/or coatings that were left exposed for an extended period of time.

Under UV light conditions, the presence and type of autofluorescence colors can distinguish sealants, clear coatings, and binding media, from darker dirt or paint layers within the stratigraphy. For instance, shellacs exhibit a distinct orange-colored autofluorescence, while natural resins (such as dammar and mastic), typically fluoresce a bright white color. Oil media tends to quench autofluorescence, while most modern, synthetic paint formulations (such as latex) exhibit no fluorescence at all. Some pigments, such as verdigris, madder, and zinc white, have distinct fluorescence characteristics, as well. UV light microscopy is critical to help distinguish otherwise identical layers often found in architectural samples— such as successive varnishes, or multiple layers of unpigmented (white) limewash.

Fluorochrome staining:

Fluorochrome stains adapted from the biological sciences were used to characterize pigments and binding media (oils, proteins, carbohydrates), in layers within the cross-section sample. The following stains were used in this analysis:

- 2,7 Dichlorofluorescein (DCF): 0.02% (w/v) in ethanol. One drop of stain was applied to the surface of the sample, blotted immediately, and cover-slipped with mineral spirits. The reaction was observed in ultraviolet light. This stain tags for oils in a sample, exhibiting a pinkish-color where unsaturated lipids are present, and yellow-green where saturated lipids are present.

- Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC): 1.0% (w/v) in ethanol. Labeling reagent for carbohydrates (gums, starches, cellulosic thickeners). One drop of stain was applied to the surface of the sample, blotted dry, and allowed to sit for approximately 45 seconds before cover-slipping, (must be allowed to react with atmospheric moisture for reaction to move forward). The reaction is observed under reflected UV light conditions (330-380 nm). A dark red-brown color is seen where carbohydrates are present.

- Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC): 0.02% (w/v) in anhydrous acetone. Fluorescent labeling reagent for proteins. One drop of stain was applied to the surface of the sample, blotted immediately, and cover-slipped with mineral spirits. The reaction was observed using the B-2A filter cube (450-490 nm). A positive reaction is a bright yellow-green fluorescence.

Pigment Identification with Polarized Light Microscopy:

To collect a pigment sample for polarized light microscopy (PLM), a surgical scalpel was used to collect a small scraping from a clean, representative area of paint. The blade was then pressed and pulled across a clean glass microscope slide, dispersing the pigment particles across the surface. The pigments were then permanently embedded under a cover slip using Cargille Meltmount (refractive index 1.66). The embedded pigments were then examined in cross and plane-polarized transmitted light with the Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope at 1000x magnification (using an oil immersion objective). The observed morphologies and optical properties (including color, refractive index, extinction), were compared to reference standards as well as literature sources before making final determinations.

Color measurement and matching:

Color measurements were taken using the Minolta Chroma Meter CR-241 colorimeter/ microscope in Susan Buck's paint analysis laboratory. Equipped with an internal 360-degree pulsed xenon arc lamp, this instrument is capable of obtaining accurate color measurements in any one of five different tristimulus color measurement systems from areas as small as 0.3mm. For the purposes of this project, color values in CIE L*a*b* colorspace and the Munsell color system were obtained.

The CIE L*a*b* color space system (developed in 1976 by the Commission International de l'Eclairage, and now an internationally accepted industry-standard color measuring system) uses three numerical values, known as "tristimulus" values, to measure color: L* is the lightness variable, representing dark to light on a scale of 0-100, while a* and b* are chromaticity coordinates, a* representing red to green on scale from -50 to +50, and b* representing blue to yellow on a scale from -50 to +50. These three coordinates are 55 used to plot the location of a color in the CIE L*a*b* colorspace.

These resulting values can be used to quantify color differences (ΔE), between two samples. To obtain this value, the following calculation is used:

ΔE = (ΔL*)½ + (Δa*)½ + (Δb*)½Generally, a ΔE value ≤ 3 cannot be perceived by the human eye. Therefore, for any two samples, ΔE values at or below this range are considered acceptable matches.

Ideally, color measurements should be collected from a clean, unweathered sample area. If necessary, a scalpel is used to scrape an area clean before color matching. Due to inherent color variations in paints (especially in hand ground, pre-industrial coatings), multiple readings are taken and averaged together to establish the final CIE L*a*b* values.

Due to the deterioration, soiling, and fragmentary nature of some early paints, color readings cannot always be obtained with the Chroma Meter. In these instances, paints are matched by eye to Munsell standard color swatches and commercial paint chips, using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. Commercial systems consulted include Benjamin Moore, Sherwin Williams, Pittsburgh Paints, and the Colonial Williamsburg Color Collection.

Appendix C. Sampling Memorandum

Loeblich: Sampling at Timson House on 4/18/08

Notes: On the south front of the house is a notch in the fascia board of the cornice that indicates where a previous door was located. It is also possible to make out the ghost of raking lines left by a door pediment in the top wide weatherboard. This does not seem to extend to the second weatherboard down though this board seems to have some age. There is also an iron plate nailed into the cornice fascia just left of the notch. The weatherboards on the north rear façade between the two later wings were also sampled and the top boards seemed to have aged. As on the front façade, the uppermost board here is wider than the rest.

| TI1 | South elevation cornice, on board with cutout notch, 1' right of end of notch, top edge of front face |

| TI2 | South elevation cornice, on board with cutout notch, right side of north edge of notch, ½' from bottom edge, on narrow face of board |

| TI3 | South elevation cornice, on board with cutout notch, 1' left of end of notch, rear side of board |

| TI4 | South elevation cornice, bed mold, in bead below ovolo, below notch |

| TI5 | South elevation cornice, crown mold, in bead on lower edge, above left side of notch |

| TI6 | South elevation cornice, soffit, front edge, 1' from left end of notch |

| TI7 | South elevation cornice, soffit, rear edge, below notch |

| TI8 | South elevation cornice, soffit, back edge, 2' from left edge of right window |

| TI9 | South elevation cornice, bed mold, in bead below ovolo, 2' left of right window |

| TI10 | South elevation weatherboard, uppermost wide board, top edge, below notch |

| TI11 | South elevation weatherboard, uppermost wide board, in bottom bead, below notch |

| TI12 | South elevation weatherboard, uppermost wide board, in bottom bead, 1' left of ghost of raking door pediment |

| TI13 | South elevation weatherboard, uppermost wide board, top edge, 1' right of open left shutter of right window |

| TI14 | South elevation weatherboard, uppermost wide board, in bottom bead, ½' from right window, behind left shutter |

| TI15 | South elevation weatherboard, 2nd board down from top, top edge, ½' from right window, behind left shutter |

| 57 | |

| TI16 | South elevation weatherboard, 2nd board down from top, top edge, below notch |

| TI17 | South elevation weatherboard, 4th board down from top, top edge, below notch |

| TI18 | South elevation, right window, top of frame on left side, 1' left of shutter hinge near top of 2nd weatherboard down |

| TI19 | North elevation weatherboard, uppermost wide board, in bottom bead, ≈5' from east wing |

| TI20 | North elevation weatherboard, 2nd board down from top, top edge, ≈5' from east wing |

Appendix D. Sampling Memorandum

Loeblich. Misc. Fragments, Sampled on 2/2/09 (Timson House fragments in red)

| TQ1 | Fragment QTR002, crown molding, top edge above large scotia, 2' from right side |

| TQ2 | Fragment QTR002, crown molding, recess of fillet below large scotia, 1' from right end |

| TQ3 | Fragment QTR001-07, backband?, interior, possibly early 19th c. (per WG), 14' in recess of fillet above cyma |

| TQ4 | Fragment QTR001-07, backband?, interior, possibly early 19th c. (per WG), 8' from left end on back corner, may have wall paints |

| VA0418-1 | Fragment VA0418, walnut paneling, top left outer corner of bottom raised panel at join of beads around panel |

| VA0418-2 | Fragment VA0418, walnut paneling, bottom left edge of bottom raised panel, on outer edge of bevel, may have original paint left from stripping |

| VA0418-3 | Fragment VA0418, walnut paneling, on side of bottom raised panel on fillet, 3' up on left side |

| VA0419-1 | Fragment VA0419, walnut paneling, center of right side of fillet on edge of middle raised panel |

| VA0419-2 | Fragment VA0419, walnut paneling, bottom right of middle panel at outer edge of bevel |

| VA0419-3 | Fragment VA0419, walnut paneling, bottom right corner on bevel of top left panel, unoriginal pigmented clear finish |

| TI21 | Fragment TMH016-07, backband or strip of wood, middle length piece, dark coating on back edge, 9' from cut end, in center of unpainted side |

| TI22 | Fragment TMH016-07, backband or strip of wood, longest piece, 5½' from cut end at back edge, may have plaster ghost |

| TR84 | Fragment TRV001-07, molding with large attached bead, charred on reverse, at join of bead and back, 3' from right on right side, may have glue residue |

| TR85 | Fragment TRV001-07, molding with large attached bead, charred on reverse, 2' from right end, in recess of cyma on right side |

| TR86 | Fragment TRV002-07, crown or bed molding, 1' from right side, in recess of fillet over large cyma |

| TR87 | Fragment TRV003-07, exterior crown molding with return, in recess of fillet over lower concave curve |

| TR88 | Fragment TRV004-07, crown or bed molding, in recess of fillet, 4' from right end, below large bead |

| TR89 | Fragment TRV004-07, crown or bed molding, in recess over large quarter round, 4½' from left end |

| TR90 | Fragment TRV005-07, crown or bed molding, bottom recess of fillet over cyma, 6' from right end |

| TR91 | Fragment TRV010-08, crown or bed molding, on right side at edge, in recess over scotia |

| WFQ21 | Fragment WFQ001-08, weatherboard, underside of bottom bead, ½' from right end |

| WFQ22 | Fragment WFQ001-08, weatherboard, top of board in lump of paint from where upper board over lapped, ½' from left end |

| WFQ23 | Fragment WFQ001-08, weatherboard, in recess of bottom bead, ½' from left end |

Appendix E. Sampling Memorandum

From: Kirsten Travers

To: Edward Chappell, Carl Lounsbury

Cc: Susan Buck

Subject: Timson House samples

On Friday, February 18, 2011, Carl Lounsbury and I met at Timson House to collect additional samples to complement those taken by Natasha Loeblich in 2008. Thirteen samples were taken. Our main intent was to obtain samples from the 19th-century eastern addition to the house, for comparison with the 18th-century section of the house. I also collected some additional samples from around the notch on the cornice (where the 18th-century porch was believed to be), as this area seems to retain good early evidence that is most important to the study.

Numbering begins at 23, continuing from Loeblich's 2008 samples. All samples were given the prefix "TI'.

| TI 23. | South elevation, left side of the notch in the cornice |

| TI 24. | South elevation, bottom edge of metal fixture on cornice, the one just to the left of the notch |

| TI 25. | South elevation, backside (north facing) of the bottom lip of the fascia, behind the metal fixture, 1' to left of notch |

| TI 26. | South elevation, east end of house (19th c. addition), cornice bed molding (ogee) above the entrance door |

| TI 27. | South elevation, east end of house (19th c. addition), cornice bed molding (base) above entrance door |

| TI 28. | South elevation, east end of house (19th c. addition), cornice soffit |

| TI 29. | South elevation, east end of house (19th c. addition), top of uppermost weatherboard, above entrance door |

| TI 30. | South elevation, east end of house (19th c. addition), bead of uppermost weatherboard, above entrance door |

| TI 31. | South elevation, east end of house (19th c. addition), top of transom above entrance door, ‧ paints already heavily accumulated, soiled, and flaking |

| TI 32. | South elevation, east end of house (19th c. addition), transom, right side, inner edge of frame. |

| 60 | |

| TI 33. | South elevation, east end of house (19th c. addition), transom sash, furthest right stile, bottom right |

| TI 34. | South elevation, east end of house (19th c. addition), entrance door architrave, east-facing edge ‧ no early paints were found on the face or in the bead of the architrave |

| TI 35. | South elevation, western end (18th-century "shed' addition), first window from west, western edge of window frame, 16' up from bottom |

| TI 36. | North elevation, westernmost window in 18th-century portion of house, underneath the jetty. |

| Window architrave, right framing member, inner edge, approx. 2' up from sill. | |

| ‧ This is a late 19th century architrave, but was taken for comparison to window architrave sampled for TI 35. | |

Appendix F. Timson Material Analytical Report (FTIR)

Date: March 13, 2009

Requester: Natasha Loeblich

Paint Analyst

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

P.O. Box 1776

Williamsburg, VA 23187

Analyst: Catherine Matsen

2001 North van Buren Street

Wilmington, DE 19802

Analysis was carried out by Catherine Matsen at the:

Scientific Research and Analysis Laboratory (SRAL)

Winterthur Museum and Country Estate

5105 Kennett Pike

Winterthur, DE 19735

SAMPLE DESCRIPTION

Timson House

Sample TI2 unknown brown material

PARTICULAR INTEREST

To characterize the light brown material found in samples from all over the Timson House using Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy.

EXPERIMENTAL

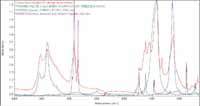

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

The unknown material was observed in cross-section photomicrographs by the requestor as a thick, translucent, light brown, early layer in reflected visible light. This material was isolated as best as possible by the requestor, though with likely contamination from white paint, and sent to the analyst. The sample was analyzed by FTIR (Fourier-transform infrared) micro-spectroscopy, an instrumental technique that permits the general classification of natural organic materials (such as waxes, proteins, oils, polysaccharides, and resins) and the specific identification of synthetic resins, inorganic pigments, and natural minerals. The submitted material from Sample TI2 was placed directly on a diamond cell and rolled flat on the cell with a steel micro-roller to decrease thickness and increase transparency. The sample was analyzed using the Thermo Scientific Nicolet Continuµm FT-IR microscope (transmission mode); data was acquired for 128 scans from 4000 to 650cm-1 at a spectral resolution of 4cm-1. Three spectra were taken from different areas 62 to ensure reproducibility and homogeneity of the sample. Spectra were collected with Omnic E.S.P. 6.1a software and analyzed in this program with various IRUG and commercial reference spectral libraries.

RESULTS

The unknown sample and reference spectra are provided in Figure 1 included with this report. The reference spectrum for beeswax is included as a general classification of a natural wax and is not a conclusive identification.

DISCUSSION