Cross-section Microscopy Analysis of Interior Paints: Robert Nicolson House (Block 7, Building 12)Robert Nicolson House Interior Paint Analysis Report_with photomicrograph appendix

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1757

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2013

CROSS-SECTION MICROSCOPY ANALYSIS REPORT

ROBERT NICOLSON HOUSE, INTERIOR FINISHES

Block 7, Building 12

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION

WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA

| Purpose | 4 |

| History | 4 |

| Previous Research | 5 |

| Procedures | 5 |

| Results | 6 |

| First-Floor Southeast Room | |

| Discussion of Results | 7 |

| Table 1. First-Floor SE Room — Paint History | 9 |

| Sample Location Photos | 10 |

| Cross-section Photomicrographs | 11 |

| Binding Media Analysis | 21 |

| Pigment ID | 24 |

| Colorimetry | 27 |

| First-Floor Northeast Room | |

| Discussion of Results | 33 |

| Table 2. First-Floor NE Room — Paint History | 34 |

| Sample Location Photos | 35 |

| Cross-section Photomicrographs | 36 |

| First-Floor Stair Passage | |

| Discussion of Results | 40 |

| Table 3. First-Floor Stair Passage — Paint History | 44 |

| Sample Location Photos | 45 |

| Cross-section Photomicrographs | 52 |

| Binding Media Analysis | 79 |

| Pigment ID | 83 |

| Colorimetry | 88 |

| First-Floor Southwest Room | |

| Discussion of Results | 91 |

| Table 4. First-Floor SW Room — Paint History | 92 |

| Sample Location Photos | 93 |

| Cross-section Photomicrographs | 94 |

| Binding Media Analysis | 99 |

| Pigment ID | 102 |

| Colorimetry | 105 |

| First-Floor Northwest Room | |

| Discussion of Results | 108 |

| Table 5. First-Floor NW Room — Paint History | 109 |

| Sample Location Photos | 110 |

| Cross-section Photomicrographs | 112 |

| Second-Floor Stair Passage | |

| Discussion of Results | 116 |

| Table 6. Second-Floor Stair Passage — Paint History | 117 |

| Sample Location Photos | 118 |

| Cross-Section Photomicrographs | 119 |

| 3 | |

| Second-Floor Present Bathroom | |

| Discussion of Results | 124 |

| Cross-Section Photomicrographs | 125 |

| Second-Floor Northeast Room | |

| Discussion of Results | 126 |

| Sample Location Photographs | 126 |

| Cross-Section Photomicrographs | 127 |

| Second-Floor Southeast Room | |

| Discussion of Results | 129 |

| Sample Location Photographs | 130 |

| Cross-Section Photomicrographs | 131 |

| Second-Floor West Passage | |

| Discussion of Results | 133 |

| Sample Location Photographs | 134 |

| Cross-Section Photomicrographs | 135 |

| Second-Floor Southwest Room | |

| Discussion of Results | 137 |

| Sample Location Photographs | 137 |

| Cross-Section Photomicrographs | 138 |

| Second-Floor Northwest Room | |

| Discussion of Results | 140 |

| Sample Location Photographs | 141 |

| Cross-Section Photomicrographs | 142 |

| Conclusions | 144 |

| References | 147 |

| Appendix A. Analytical Procedures | 148 |

| Appendix B. Sample Memo (E. Chappell, July 26, 2013) | 151 |

| Appendix C. Sample Memo (K. Travers, July 3, 2013) | 154 |

| Appendix D. Sample Memo (K. Travers, August 9, 2013) | 155 |

| Appendix E. Photomicrograph Contact Sheet | attached |

Robert Nicolson House Interior, Cross-Section Microscopy Report

September 2013

Robert Nicholson House exterior, block 7, building 12 [history.org]

Robert Nicholson House exterior, block 7, building 12 [history.org]

| Structure: | Nicholson House, block 7, building 12 |

|---|---|

| Requested by: | Edward Chappell Roberts Director of Architectural and Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation |

| Analyzed by: | Kirsten Travers, Paint Analyst, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation |

| Consulted: | Susan L. Buck, Ph.D., Conservator and Paint Analyst, Williamsburg, Virginia |

| Date submitted: | September 2013 |

Purpose:

The goal of this project is to use cross-section microscopy techniques to explore the early interior paint history of the Robert Nicholson House, to better understand the arrangement of spaces and finish, as well as the evolution of spaces in the early history of the building.

Another objective was to determine if the two known periods of construction (see History section below) could be identified through the paint stratigraphy, and if the paint could shed light on how much time elapsed between these periods.

History:

Dendrochronology indicates the Nicolson House was built c. 1751 on what was at that time, the outskirts of Williamsburg1 (Heikkenen 1990, 2). The earliest section [the east portion] was a story-and-one-half, gambrel roof dwelling with a double pile side passage plan. In 1764, Nicolson added the two-bay extension on the west end, creating a more symmetrical five-bay, central passage plan. The date of the west extension was also confirmed through dendrochronology (Heikkenen, ibid).

Robert Nicolson was a merchant and tailor who was prominent in civic affairs, but from 1755 to 1777 he was also taking in lodgers at his residence. He appears to have conducted his business off-site, since he is recorded as having a tailoring shop "across the road" (no longer extant), and he later moved his business to the store on Duke of Gloucester street still known today as the Nicholson Shop. He lived in the house on York street until his death in 1797 (Wenger 1986, and Savedge, 1976).

Previous Research:

In 2006, Susan Buck examined two exterior samples (window frame and the cornice, collected by Ed Chappell), to facilitate the imminent repainting of the house. The period of interpretation was 1764, when the house achieved its present form. Buck determined that the two periods of construction were reflected in the paints, and that there were approximately sixteen generations extant, with the earliest (1764) paint being a "medium tan" color, and generations 2-5 being cream-colored. Generation two was chosen for matching, as this reflected the second period color (Buck 2006, 1).

In May 2007, Natasha Loeblich took a more extensive look at additional samples from exterior surfaces (cornice, window trim, front and rear doors), which resulted in a re-interpretation of some of the earlier findings. She also found that the two periods of construction were reflected in the paint stratigraphy, but she did not find the medium tan color. Samples from the two easternmost windows on the front elevation begin with four generations of cream-colored paint, with generation five containing zinc white (post 1845). Samples from the western windows, which date to the second period of construction, contained only two generations of cream-colored paint, before the fifth generation zinc white paint. This suggested that the house was painted twice with cream-colored paints before the addition was constructed. No early paints could be found on the cornice.

The front and rear doors had similar early paints and appeared to be first period. The first generation finish on both doors is a cream-colored base coat and a black finish coat. Generation two is another black paint. Both generations were very worn and disrupted, suggesting a long period of exposure (Loeblich 2007, 20).

Procedures:

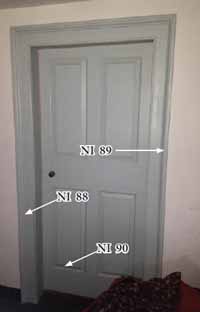

To date, 103 paint samples have been removed from the Nicolson House interior by Kirsten Travers (Paint Analyst), accompanied by Edward Chappell (Roberts Director of Architectural and Archaeological Research). On site, a monocular 30x microscope was used to examine the painted surfaces to determine the most appropriate areas for sampling. A microscalpel was used to remove the samples, and sampling locations were recorded and photographed. Samples were labeled and stored in small, individual Ziploc bags for transport. All samples were given the prefix "NI", and numbered according to the space where they were taken (see Appendix C for floor plans and numerical designation of rooms), and the order in which they were collected. A complete list of sample locations is found in Appendix B.

In the laboratory, the samples were examined with a stereomicroscope under low power magnification (5x to 50x), to identify those that contained the most paint evidence and would therefore be the best candidates for cross-section microscopy. Uncast portions were retained for future examination and analysis, if necessary. The best candidates were cast in resin cubes and sanded and polished to expose the cross-section surface for microscopic examination. Please see Appendix A for sample preparation details.

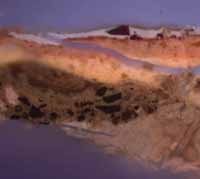

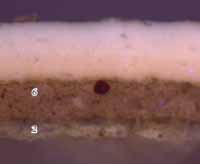

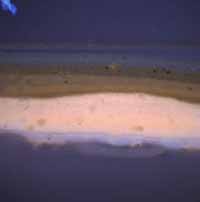

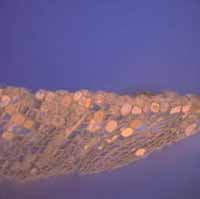

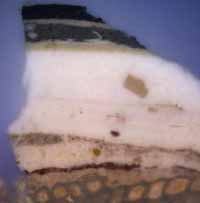

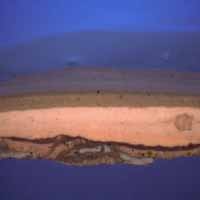

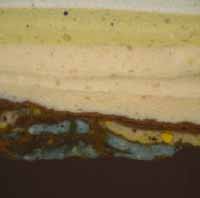

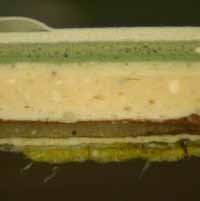

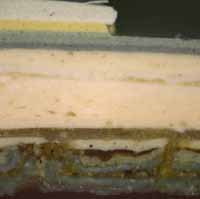

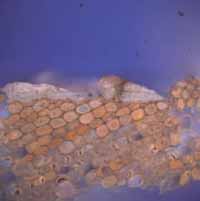

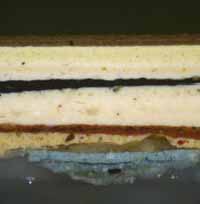

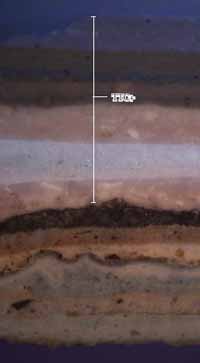

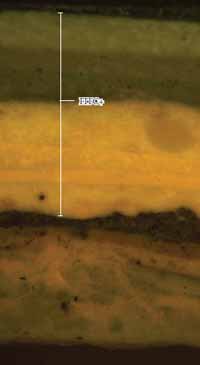

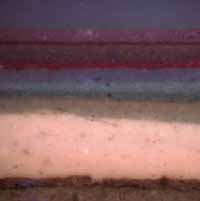

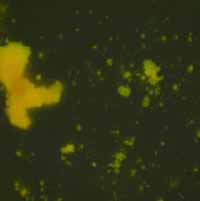

The cross-section samples were examined and digitally photographed in reflected visible and ultraviolet light conditions at 100x to 400x magnifications. By comparing the resulting photomicrographs, finish generations could be interpreted based on physical characteristics such as color, texture, thickness, presence of dirt layers and extent of surface deterioration.

Results:

This study found significant paint evidence on woodwork throughout the house that sheds light on the early color schemes and structural evolution of the interior. In this report, the results are organized according to room: the first-floor southeast room is discussed first, followed by the first-floor northeast room and the stair passage, these being Period 1 (c.1751) spaces. This is followed by the first-floor southwest room and northwest room, which date to Period 2 (c.1764).

The report continues with second-floor spaces, starting with the stair passage and eastern rooms (again, these date to Period 1), and the spaces at the western end of the house, which date to Period 2 (c.1764).

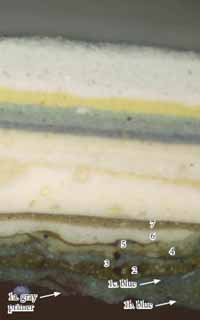

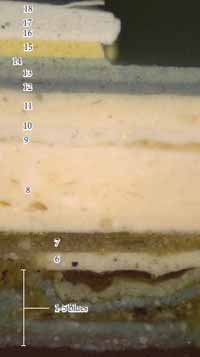

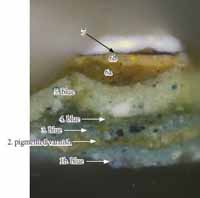

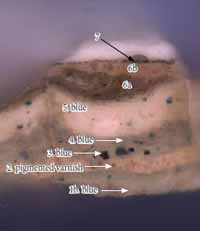

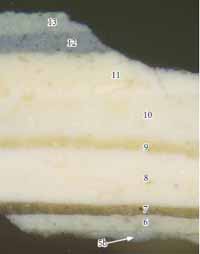

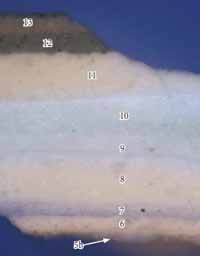

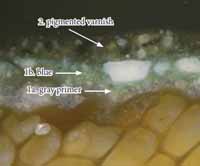

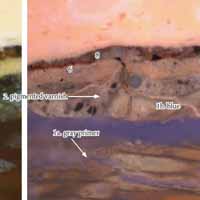

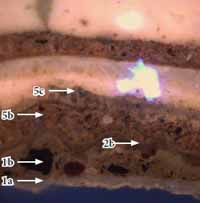

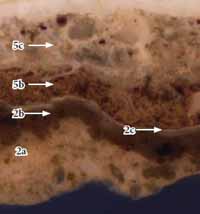

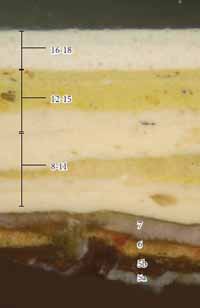

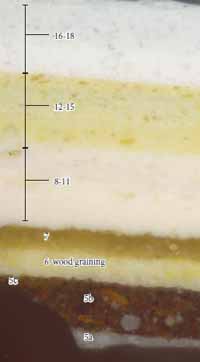

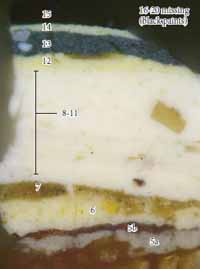

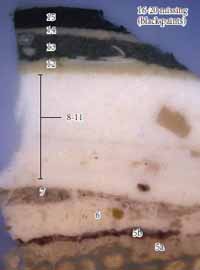

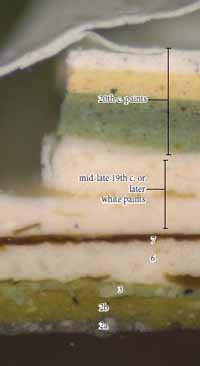

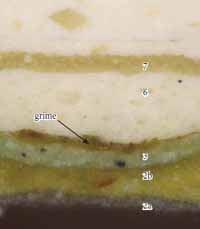

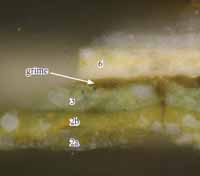

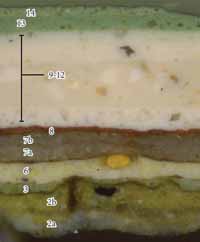

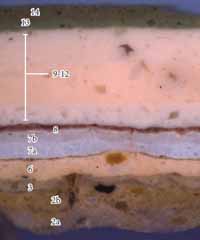

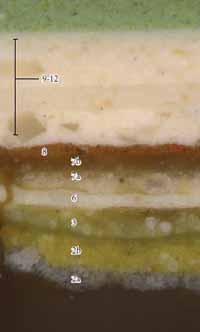

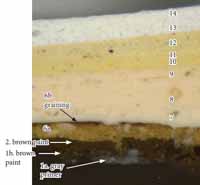

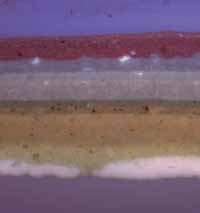

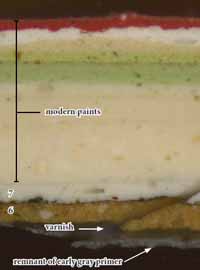

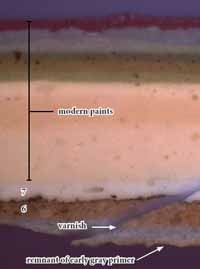

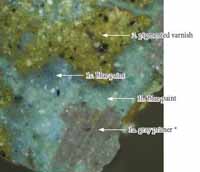

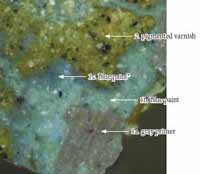

Photomicrographs of paint stratigraphies have been annotated according to finish generation. For instance, a primer, paint layer, and varnish may represent one finish generation and are all given the same number, but differentiated with lowercase letters (1a, 1b, 1c, etc.). Since many samples contained redundant evidence, only the most relevant cross-section photomicrographs are presented in this report. The analytical results and pertinent observations are discussed adjacent to the photomicrographs. The results are interpreted in the conclusion, and all raw photomicrographs can be found in the appendix at the end of this report.

First-Floor Southeast Room [Room 107]

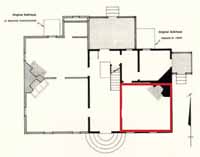

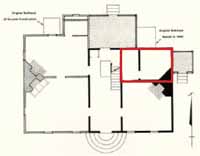

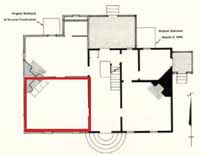

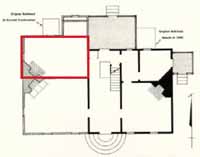

First floor plan, Robert Nicolson House Southeast room is outlined in red

First floor plan, Robert Nicolson House Southeast room is outlined in red

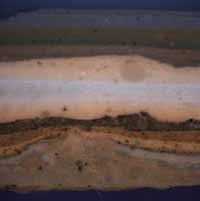

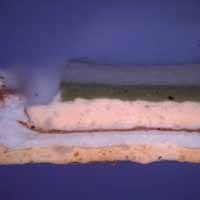

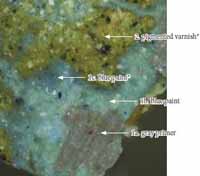

Discussion of Results: This study found that the woodwork in the first-floor southeast room retains excellent, intact paint evidence that elucidates the decorative and structural history of this room. The first five finish generations are deep blue paints, and the presence or absence of certain generations helped reconstruct the history of this room in two specific phases (see photomicrographs below), in particular, that the wainscot panelling is later than the rest of the woodwork.

According to the architectural report (Wenger 1986, 35), parts of the mantel are original. However, on site multiple excavations were made and this element appeared to contain only modern paints, and was not sampled.

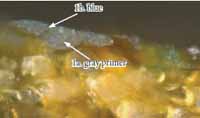

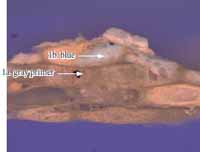

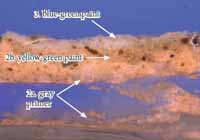

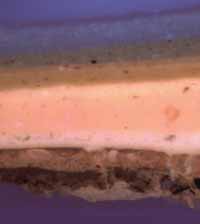

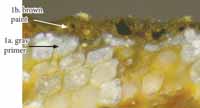

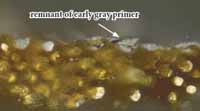

Generation 1: This reflects the earliest form of the house, which dates to c.1751 and consists of the stair passage and eastern rooms on the first and second floors, including this room. The paint analysis suggests that in this period, the woodwork in this room was sealed with shellac (identified by its orange autofluorescence in the wood cells), and primed with a thin gray-colored primer (generation 1a), made with lead white, chalk, carbon black, and a few earth pigments. This is the same gray primer used in the adjacent stair passage (see Stair Passage section, p. 40). This primer was then painted with two layers of deep blue-green paint (generations 1b and 1c), composed of lead white, Prussian blue, and a small amount of yellow earth pigment. There is a very thin layer of grime on the surface of this paint.

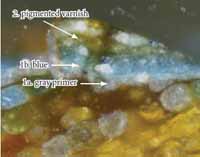

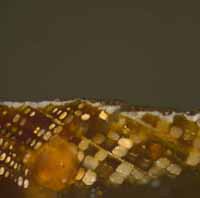

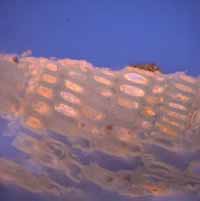

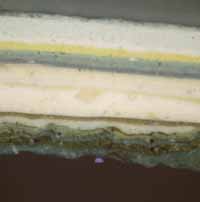

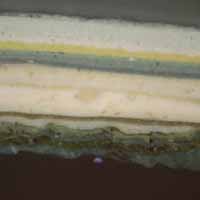

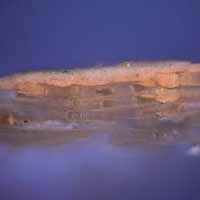

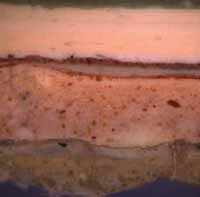

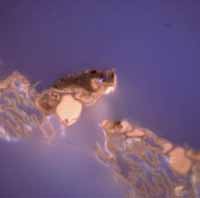

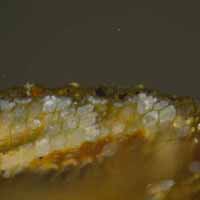

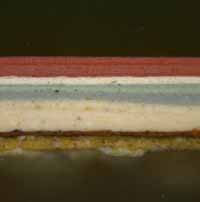

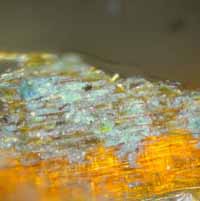

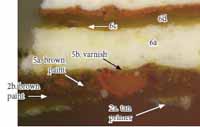

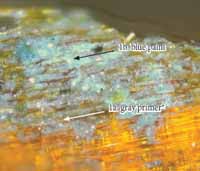

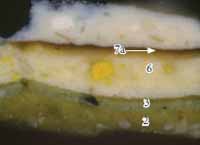

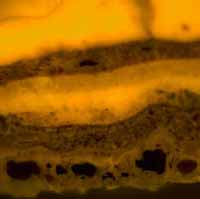

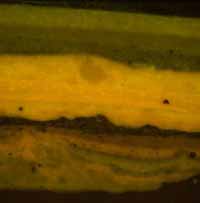

NI 43b, visible light, 400x (door leaf to passage)

NI 43b, visible light, 400x (door leaf to passage)

NI 43b, UV light, 400x (door leaf to passage)

NI 43b, UV light, 400x (door leaf to passage)

The presence of this paint helped identify first period elements. It was found on the west wall door architrave and leaf (see samples NI 42 and 43, pp. 11-14), the north wall door architrave and leaf (NI 69 and 70, pp. 15-16), and the window architraves on the south wall (NI 66, p. 17). Although only the easternmost window was sampled, the western window was examined and found to contain the same paints.

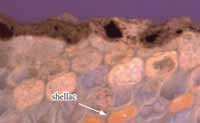

Generation 2: This paint was also found on all first period elements. In cross-section, this layer is thick, translucent, and greenish, with small dark particles suspended within it. Under UV light, it has a brighter, orange-colored autofluorescence suggestive of a shellac resin, which would have been very glossy. PLM determined that the dark pigment particles are actually indigo, a blue pigment that is known to have been imported into Williamsburg, but one that has not yet been identified in a house interior to date (based on the author's knowledge). Although today this finish is very green (see color match, p. 30), this could result from oxidation of the resinous media, and/or pigment fading (Bristow 1996, 14). The actual color would have to be determined through mock-ups using traditional materials.

Generations 3 and 4: These paints were also found on all first period elements. Both generations are coarsely ground blue paints of almost identical color. In most samples, they looked like a single generation with no boundary between them, suggesting they were applied within a relatively short period of time. However, a few samples illustrated this boundary (see sample NI 43, p. 13), suggesting these are actually two separate, albeit very similar, paint generations.

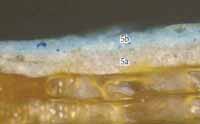

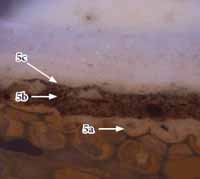

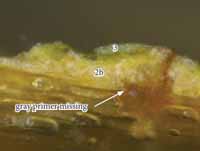

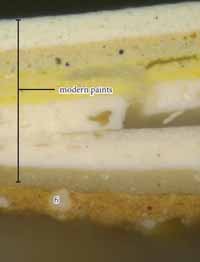

Generation 5: This was the earliest paint on the wainscot panels and baseboards (see samples NI 44-46, pp. 18-20), an indication that these elements are later. This finish consists of a gray primer (generation 5a) and a blue paint (generation 5b), which is somewhat lighter in color than the previous blue paint generations. This paint is covered by a thick layer of grime and dirt, suggesting it was exposed for a relatively long period of time.

It seems likely that the wainscot in this room is contemporary with the wainscot panelling in the adjacent stair passage, which was also later. It is estimated that the wainscot in the stair passage was installed c.1777. Therefore the wainscot in this room would have the same approximate date.

Binding media analysis was inconclusive regarding these early paints (pp. 21-23). However, visual analysis suggests they are traditional oil-bound paints (with the exception of generation 2, which appears to have a resinous binder).

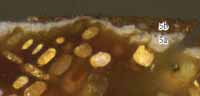

Generation 6: This finish was found throughout the first floor of the house. This scheme consisted of faux-wood grained door leaves, stairs, and baseboards, possibly in imitation of a light-colored wood, such as oak, with the architraves and wainscot painted a cream color. The wainscot caps, stair handrails and newel posts appear to have been painted to imitate a more orange-red-colored wood. This scheme is consistent with an early 19th-century date, and most likely reflects the period of the Power occupancy (1803 - c.1840).

Generation 7: This scheme consists of a finely ground, resinous grayish-colored paint on the door architraves, wainscot, and baseboard. This paint has a bright bluish, twinkling autofluorescence characteristic of zinc white (ZnO), a pigment that was not commercially available in housepaints until c.1845. During this same period, the door leaves, window architraves, and chair rails were painted black.

Generations 8-11: These paints are all finely ground, smooth, and consistent white paints that appear to have been industrially prepared, and probably date to the late 19th or early 20th century.

9Generations 12-14: These are blue-colored paints, the earliest of which probably dates to 1940, when Cogar restored the house. Cogar noted in his diary that rudimentary paint scrapes carried out by himself and his mother found that the first paint in the passage was yellow. It seems likely that these scrapes were carried out on one of the doorways on the west wall, where the wood was first painted with a yellow-tan primer (generation 2a).

Generation 15: This generation is a modern, yellow-colored paint.

Generations 16-18: These represent the present pale blue, or 'pearl' colored paints in the passage.

| Paint Generation | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 16-18 | pale blue paints, modern | current finish |

| 15 | deep yellow paint, modern | |

| 12-14 | blue paints, modern | possibly Cogar-era (1940) |

| 8-11 | white paint, post-industrial | late 19th or early 20th c. |

| 7 | gray paint on door architraves and wainscot, black door leaves, window architraves and wainscot cap | gray paint contains zinc white (ZnO), post c.1845 |

| 6 | faux wood graining (6a-6d), possibly oak, door leaves and wainscot caps. Cream-colored paint on rest of woodwork. | Same scheme in other first-floor rooms. |

| 5 c.1777 | gray primer (5a), blue paint (5b). Very grimy | earliest paint on wainscot |

| 4 | blue paint | |

| 3 | blue paint | |

| 2 | blue or blue-green glossy layer, made with indigo suspended in resin | also found in adjacent NE room |

| 1 c.1752 | gray primer (1a), coarsely ground blue paint (1b and 1c), grime | also found in adjacent NE room |

First-Floor Southeast Room [Room 107] — Sample Locations

north wall, doorway to present kitchen

north wall, doorway to present kitchen

Sample NI 42: west wall, door architrave (north), backband cyma

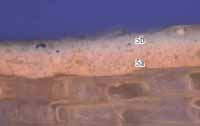

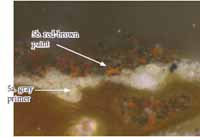

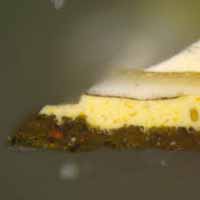

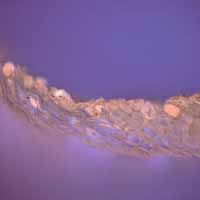

NI 42b, visible light, 200x (different section of sample) Lightened for greater legibility in PS

NI 42b, visible light, 200x (different section of sample) Lightened for greater legibility in PS

NI 42b, visible light, 200x (different section of sample) Lightened for greater legibility in PS

NI 42b, visible light, 200x (different section of sample) Lightened for greater legibility in PS

Sample NI 43: west wall, door leaf, bottom right panel, right bevel

14Sample NI 69: Door architrave to northeast room (current kitchen). Right (east) architrave, cyma of backband, 30" above floor

Sample NI 70: Door leaf to northeast room (current kitchen), bottom left panel, beveled underside

Sample NI 66: South wall, window architrave, right side, cyma, 10" up from bottom

Sample NI 44: west wall, wainscot stile immediately adjacent to right side of passage door

The samples from the wainscot on the south wall [not shown] began with the same fifth generation gray primer and blue paint.

Sample NI 45: west wall, chair rail, underside of cap

First-Floor Southeast Room [Room 107] — Binding Media Analysis

Sample NI 43: west wall, door leaf, bottom right panel, right bevel

TTC stain for carbohydrates (starches, gums, cellulosic fillers)

NI 43, UV light, 200x. Before TTC stain.

NI 43, UV light, 200x. Before TTC stain.

NI 46a, UV light, 200x. TTC reaction.

NI 46a, UV light, 200x. TTC reaction.

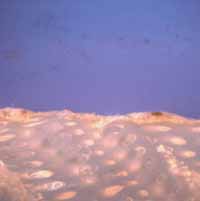

Sample NI 43 was stained with TTC to tag carbohydrates in the stratigraphy.

Strong positive reactions (dark, reddish-brown color), were observed in the modern paints (generations 6-18). No reactions were observed in the earliest paints.

FITC stain for proteins (animal glues, casein)

NI 43, B-2A filter, 200x. Before FITC stain.

NI 43, B-2A filter, 200x. Before FITC stain.

NI 46a, B-2A filter, 200x. FITC reaction.

NI 46a, B-2A filter, 200x. FITC reaction.

Sample NI 43 was stained with FITC to tag proteins in the stratigraphy.

Positive reactions (yellow-green fluorescence) were observed in the modern paints (generations 8-18). No reactions were observed in the earliest paints.

DCF for lipids (oils)

NI 43, B-2A filter, 200x. Before DCF stain.

NI 43, B-2A filter, 200x. Before DCF stain.

NI 46a, B-2A filter, 200x. DCF reaction.

NI 46a, B-2A filter, 200x. DCF reaction.

Sample NI 43 was stained with DCF to tag lipids (oils) in the stratigraphy.

Strong positive reactions (yellow-green fluorescence), were observed in the modern paints (generations

8-18). No reactions were observed in the earliest paints.

First-Floor Southeast Room [Room 107] - Pigment ID

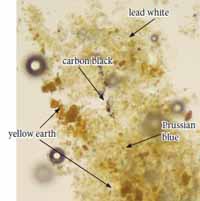

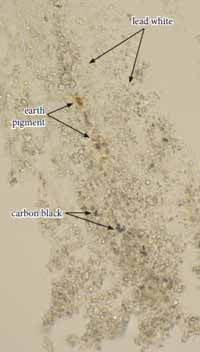

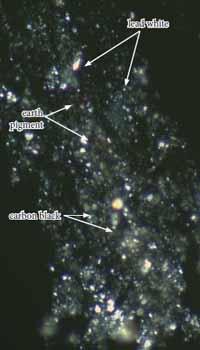

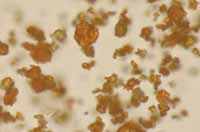

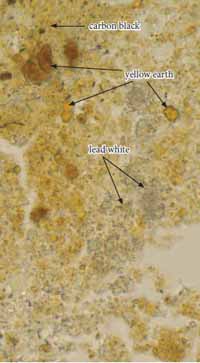

Generation 1a: gray primer

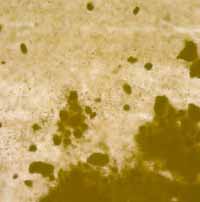

dispersed pigment sample from gray primer, sample NI 43 (door leaf), plane polarized light, 1000x

dispersed pigment sample from gray primer, sample NI 43 (door leaf), plane polarized light, 1000x

dispersed pigment sample from gray primer, sample NI 43 (door leaf), cross polarized light, 1000x

dispersed pigment sample from gray primer, sample NI 43 (door leaf), cross polarized light, 1000x

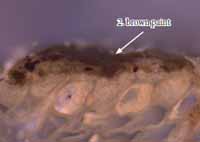

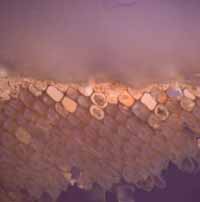

The first generation gray primer (generation 1a), is comprised of mostly lead white pigment (2PbCO3 ⋅ Pb(OH)2), visible as very small, rounded transparent particles with high relief and a bright birefringence in crossed polars.

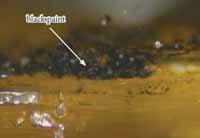

Some carbon black particles were also seen, which were black and opaque in transmitted light, and dark under crossed polars. These particles were very fine and could be lampblack pigment.

A few agglomerations of golden-brown-colored particles were present, which are dark under crossed polars. These could be some type of earth pigment — possibly a yellow ochre, a sienna, or an umber. The exact type of pigment could not be determined.

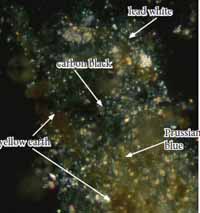

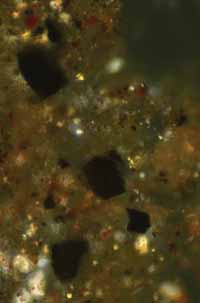

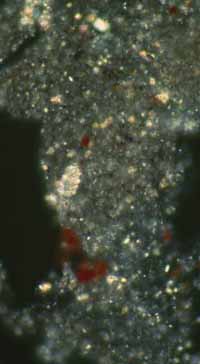

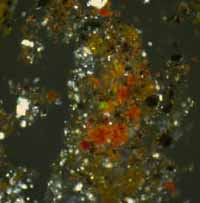

Generation 1b,c: blue paint (two layers could not be isolated)

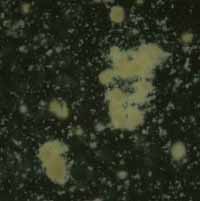

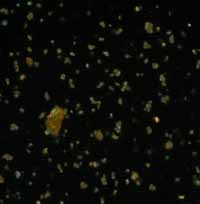

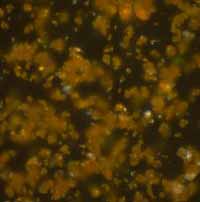

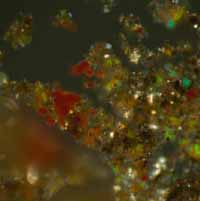

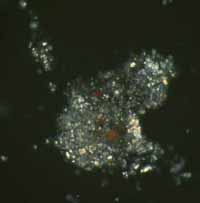

dispersed pigment sample from first generation blue paint, sample NI 43 (door leaf), plane polarized light, 1000x

dispersed pigment sample from first generation blue paint, sample NI 43 (door leaf), plane polarized light, 1000x

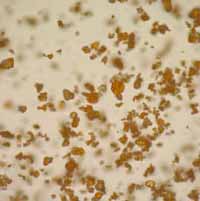

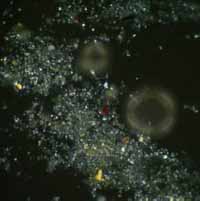

dispersed pigment sample from first generation blue paint, sample NI 43 (door leaf), cross polarized light, 1000x

dispersed pigment sample from first generation blue paint, sample NI 43 (door leaf), cross polarized light, 1000x

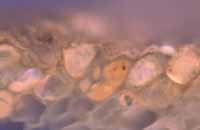

The pigment samples from the first generation blue paints (generations 1b and 1c could not be isolated) appear to contain primarily lead white pigments (2PbCO3 ⋅ Pb(OH)2), visible as small, rounded particles with high relief, that are colorless in transmitted plane polarized light and have a bright birefringence in cross polarized light.

Particles of Prussian blue (Fe4[Fe(CN)6]3), were also present, visible as bright blue particles in a range of shapes and sizes, always with low relief, soft edges, and a 'smeary' quality in some areas. This pigment is isotropic (dark) in crossed polars.

A few agglomerations of yellow and golden-brown-colored particles were also seen, which are dark under crossed polars. These appear to be an earth pigment — most likely a yellow ochre, in addition to a sienna or an umber. The exact type of earth pigment could not be determined.

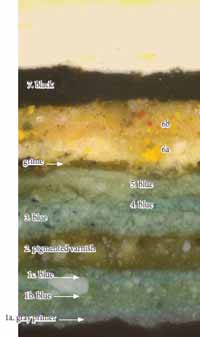

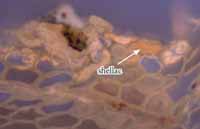

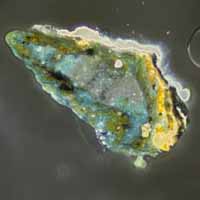

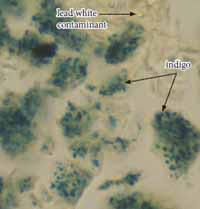

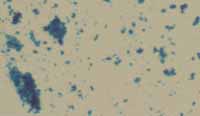

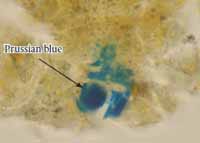

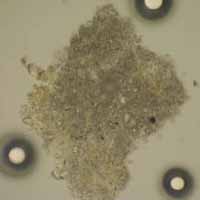

Generation 2: pigmented varnish

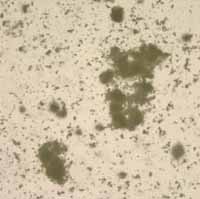

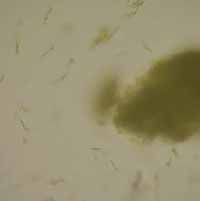

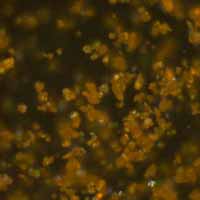

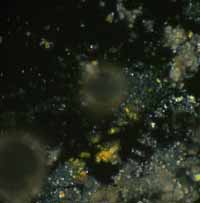

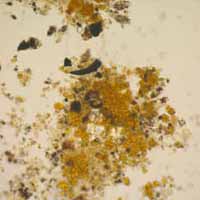

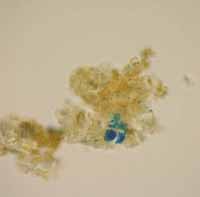

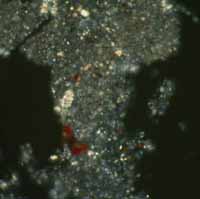

dispersed pigment sample from second generation pigmented glaze, sample NI 43 (door leaf), plane polarized light, 1000x

dispersed pigment sample from second generation pigmented glaze, sample NI 43 (door leaf), plane polarized light, 1000x

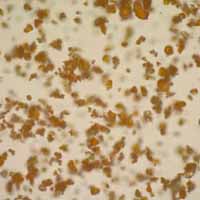

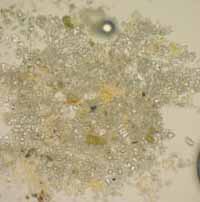

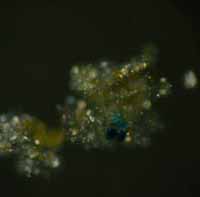

dispersed pigment sample from second generation pigmented glaze, sample NI 43 (door leaf), cross polarized light, 1000x

dispersed pigment sample from second generation pigmented glaze, sample NI 43 (door leaf), cross polarized light, 1000x

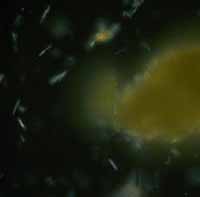

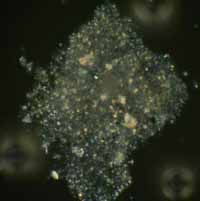

reference sample of indigo, plane polarized light, 1000x (note this is not embedded in resin as above)

reference sample of indigo, plane polarized light, 1000x (note this is not embedded in resin as above)

reference sample of indigo, cross polarized light, 1000x

reference sample of indigo, cross polarized light, 1000x

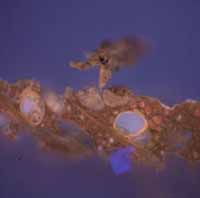

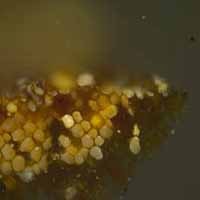

In cross-section, the second generation finish appears to be a pigmented glaze, consisting of large, dark particles suspended in a translucent, greenish-colored matrix. This matrix has a brighter autofluorescence in UV, suggestive of a resinous composition.

The dispersed pigment sample contains fine-grained particles of a dark blue color. Particle shape is rounded and size range is narrow with some larger agglomerations of particles. The pigment is isotropic. This matches the literature descriptions (Eastaugh 656), and reference samples of indigo (see bottom images).

Under crossed polars, a few colorless particles with bright birefringence were observed. These could be lead white pigments from surrounding paints, as well as chalk, clay, or another inert extender sometimes associated with indigo (ibid).

First-Floor Southeast Room [Room 107] — Colorimetry

Generation 1a: gray primer in southeast room and stair passage

Sample NI 43 (door leaf), uncast, 100x

Sample NI 43 (door leaf), uncast, 100x

Accurate color readings for the first generation gray primer used in the southeast room and stair passage could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter because this layer was very thin and a clean, intact area could not be isolated for measurement. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest match for the gray primer was determined to be Benjamin Moore 2134-30 "Iron Mountain".

Benjamin Moore

Benjamin Moore

2134-30

"Iron Mountain"

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 36.27 | +0.10 | +1.09 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 2.3Y | 3.5 | 0.1 |

Generation 1b: blue paint (layer 1)

Sample NI 43 (door leaf), uncast, 100x

Sample NI 43 (door leaf), uncast, 100x

Accurate color readings for the second layer of the first generation blue finish (generation 1b), used in the southeast room could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter because this layer was very thin and a clean, intact area could not be isolated for measurement. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest match for the gray primer was determined to be Sherwin Williams SW 6222 "Riverway".

Sherwin Williams

Sherwin Williams

SW 6222

"Riverway"

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45.33 | -6.94 | -4.76 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 1.3B | 4.4 | 1.8 |

Generation 1c: blue paint (final layer)

Sample NI 43 (door leaf), uncast, 100x

Sample NI 43 (door leaf), uncast, 100x

Accurate color readings for the final layer of the first generation blue finish (generation 1c), used in the southeast room could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter because this layer was very thin and a clean, intact area could not be isolated for measurement. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest match for the gray primer was determined to be Benjamin Moore HC-158 "Newburg Green".

Benjamin Moore

Benjamin Moore

HC-158

"Newburg Green"

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 35.30 | -4.64 | -8.90 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 7.8B | 3.4 | 2.3 |

Generation 2: pigmented varnish

Sample NI 43 (door leaf), uncast, 100x

Sample NI 43 (door leaf), uncast, 100x

Accurate color readings for the second generation finish (pigmented varnish), used in the southeast room could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter because this layer was very thin and a clean, intact area could not be isolated for measurement. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest match was determined to be Benjamin Moore HC-134 "Tarrytown Green".

Benjamin Moore

Benjamin Moore

HC-134

"Tarrytown Green"

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 34.72 | -8.49 | -0.64 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 3.1BG | 3.4 | 1.6 |

Generations 3 & 4: blue paints

The third and fourth generation blue paints were examined with low-power magnification and both appear to be the same color. Accurate color readings for these blue paints could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter because a clean, intact area could not be isolated for measurement. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest match was determined to be Sherwin Williams #0047 "Studio Blue Green".

Sherwin Williams

Sherwin Williams

#0047

"Studio Blue Green"

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51.81 | -9.61 | -0.58 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 3.6BG | 5.1 | 1.8 |

Generation 5b: blue paint (first finish on wainscot)

Accurate color readings for the fifth generation blue finish (generation 5b), used in the southeast room could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter because this layer was very thin and a clean, intact area could not be isolated for measurement. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest match was determined to be Benjamin Moore HC-150 "Yarmouth Blue".

Benjamin Moore

Benjamin Moore

HC-150

"Yarmouth Blue"

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 77.64 | -4.98 | -3.48 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 3.7B | 7.7 | 1.3 |

First-Floor Northeast Room [Rooms 106 and 108]

First floor plan, Robert Nicolson House

First floor plan, Robert Nicolson House

Northeast room is outlined in red

Discussion of Results: The early paint history of the woodwork in this room is very similar that of the adjacent southeast room, and suggests that during the Nicolson period (1751-1797), these rooms were painted in the same manner, and therefore chromatically linked. Since this room contains the same early paints as the southeast room, fluorochrome staining, color matching, and pigment ID were not carried out.

This room is the present kitchen, and as such as been much re-worked. There is not as much original woodwork here as in the other rooms, and no wainscot. Fewer samples were taken from this space, and the early paints in general were more disrupted. However, there was more than enough evidence to determine that some of the existing woodwork dates to Period 1 (c.1751).

Generation 1: Like the southeast room, the woodwork in this room was sealed with shellac, primed with a thin gray-colored primer (generation 1a), and painted with two layers of deep blue-green paint (generations 1b and 1c).

The presence of this paint helped identify first period elements. It was found on the south wall door leaf and architrave (see samples NI 72 and 71, pp. 36 and 38), the door architrave to the passage (NI 74, p. 37), and the chair rail on the south wall (NI 73, p. 39).

Generation 2: This paint was also found on all first period elements. It is the pigmented varnish (indigo) that was used in the adjacent southeast room.

Generation 3: Another blue paint. This is the final early blue paint layer, whereas the adjacent southeast room was painted blue up to five times. This suggests that the northeast room was not painted as often by comparison. The third generation blue paint is very grimy and exposed for a long period of time.

Generations 4 and 5: Compared to the adjacent southeast room, this room appears to have been unpainted during these periods.

Generation 6: This is the faux-wood graining scheme found throughout the first floor of the house.

Generation 7: Compared to the adjacent southeast room, this room appears not to have been repainted during this period.

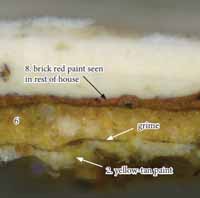

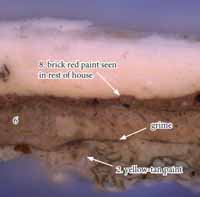

34Generation 8: It appears that all of the woodwork in this room was painted a brick red color. This paint was found throughout the first floor of the house.

Generations 9-16: These are thick paints with smooth surfaces and finely ground pigment particles, suggestive of modern paints. The present color is red-brown.

| Paint Generation | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 9-16 | modern white, black, and red-brown paints | present color red-brown |

| 8 | brick red paint | also in stair passage |

| 7 | not repainted | — |

| 6 | faux wood graining (6a-6d), possibly oak, door leaves and wainscot caps. Cream-colored paint on rest of woodwork. | Same scheme in other first-floor rooms. |

| 5 | not repainted | blue in adjacent SE room |

| 4 | not repainted | blue in adjacent SE room |

| 3 | blue paint | also in adjacent SE room |

| 2 | blue or blue-green glossy layer, made with indigo suspended in resin | also in adjacent SE room |

| 1 c.1752 | gray primer (1a), coarsely ground blue paint (1b and 1c), grime | also in adjacent SE room |

First-Floor Northeast Room [Rooms 106 and 108] — Sample Location Photos

Sample NI 72: south wall, door leaf, lock rail, west edge

Sample NI 74: West wall, door architrave to passage, south side, fascia, 16" up from floor

Sample NI 71: south wall, door architrave, east side, fascia, 18" up from floor

First-Floor Stair Passage [Room 105]

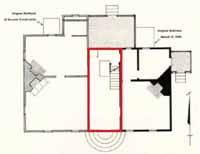

First floor plan, Robert Nicolson House

First floor plan, Robert Nicolson House

Stair passage is outlined in red

Discussion of Results: This study found that the stair passage woodwork retains excellent, intact paint evidence to confirm some of the known construction history of the space, in particular the first period finish in 1751 and the finish after the western expansion c.1764, as well as to clarify how this space changed after that period.

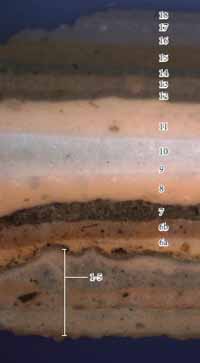

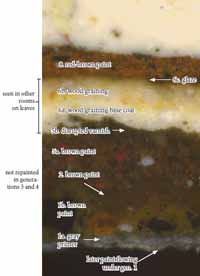

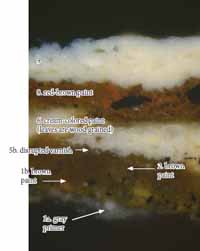

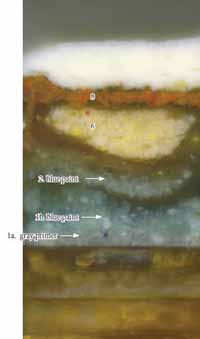

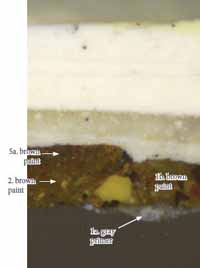

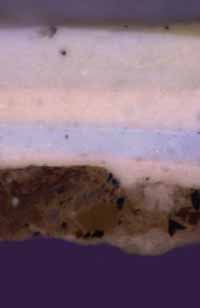

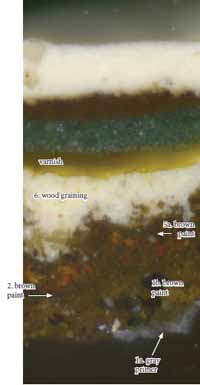

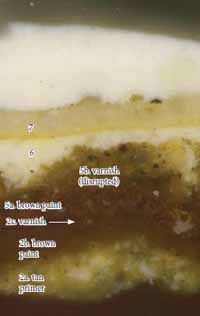

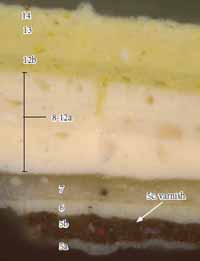

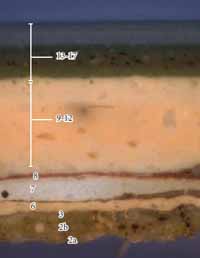

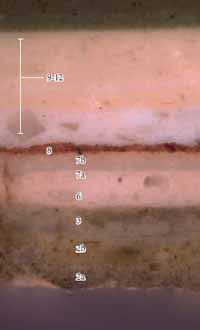

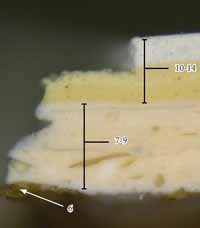

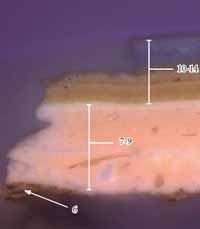

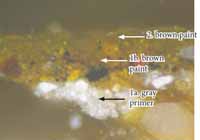

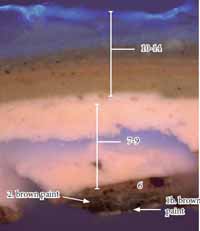

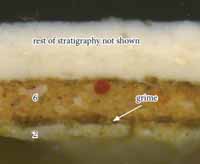

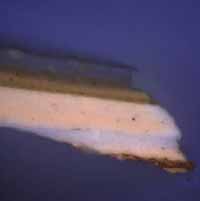

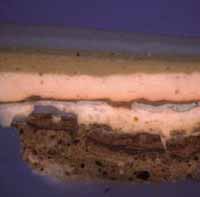

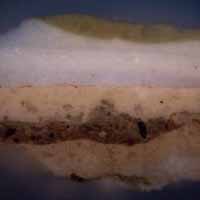

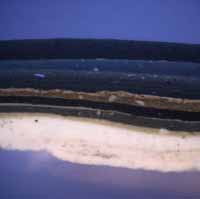

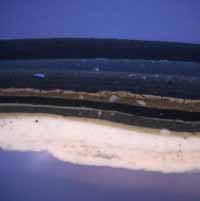

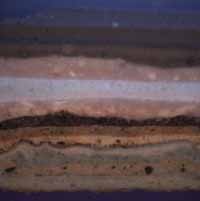

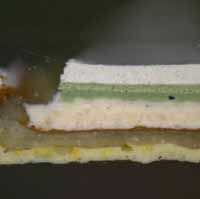

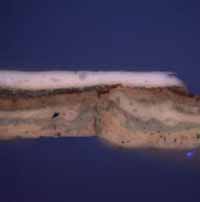

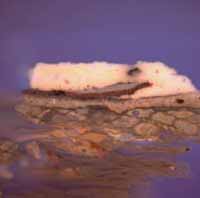

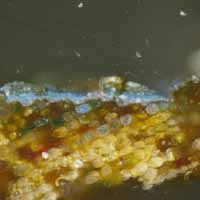

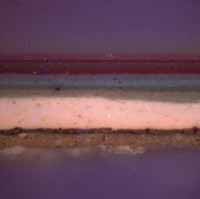

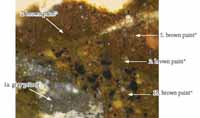

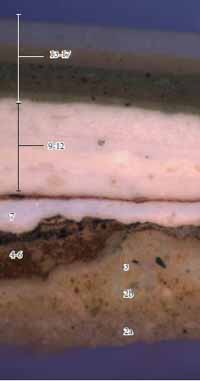

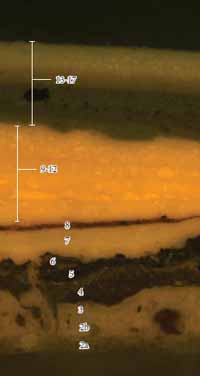

The first three finish generations (generations 1, 2, and 5), are dark brown paints of almost identical color, which, at high magnification, have very different appearances in visible and UV light. Characteristics such as pigment composition and autofluorescence were important factors in identifying each individual generation. The presence or absence of certain generations helped reconstruct the history of this room in three specific phases. Please refer to page 43 for the three best photomicrographs illustrating these phases.

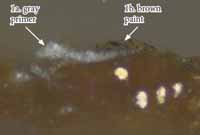

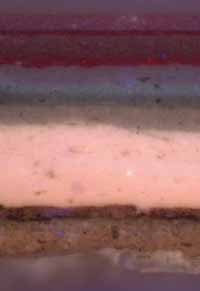

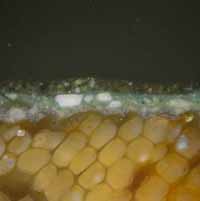

Generation 1: This reflects the earliest form of the house, which dates to c. 1751 and consists of the stair passage and eastern rooms on the first and second floors. The paint analysis suggests that in this period, the woodwork in the passage was sealed with shellac (identified by its orange autofluorescence in the wood cells), and primed with a thin gray-colored primer (generation 1a), made with lead white, chalk, carbon black, and a few earth pigments. This is the same gray primer used in the adjacent eastern rooms. The woodwork was then painted with a dark brown paint (generation 1b), that was very coarsely ground, and contained large chunks of carbon black pigments, red lead pigments, and earth pigments ranging from deep red, brown, and yellow. These large pigment particles made this first generation dark brown paint easy to identify in all of the cross-section samples. This paint was coated with a very thin layer of autofluorescent material, probably a plant resin varnish (generation 1c), which would have created a glossy surface. This varnish was worn away in most samples and was not always present. The best example of this finish was found in sample NI 39, taken from the door leaf to the cellar stair (see p. 52).

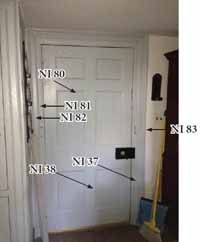

The presence of this first generation finish helped identify the first period woodwork in the passage. This finish was found on the entire staircase (see samples NI 2, 9, 15, 18; pp. 52-55), and stair stringer (NI 3, p. 56). It was also found on the cellar door leaf and architrave (NI 39, 40; pp. 54-57), the north entrance door leaf and architrave (NI 80, 81; pp. 59-60), the south entrance door leaf and architrave (NI 79, 78; pp. 65-66), the door architrave leading to the northeast room (NI 75, p. 62), and the door leaf and architrave leading to the southeast room (NI 22, 20; pp. 63-64). It should be noted that the east jamb of the north (original, rear) door architrave might have been moved from one of the eastern rooms, since the paint history of that jamb more closely resembles the paints in those spaces (NI 83, p. 61).

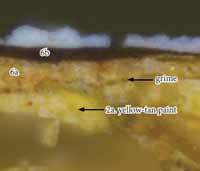

41Most importantly, the first generation paint was NOT found on the two doorways leading to the west room, the wainscot, or the closet in the northwest corner, which confirms that these elements post-date the first period.

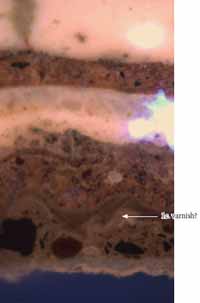

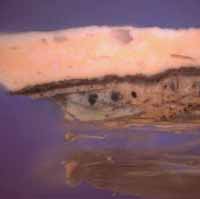

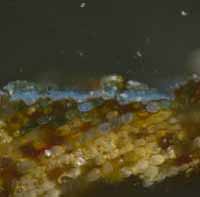

Generation 2: This reflects the second form of the house, when the western addition was constructed c.1764. During this period, the passage woodwork was re-painted with another dark brown paint (generation 2b). Although it is the same color as the previous generation, this paint is much more finely-ground, and has a very dim autofluorescence in UV light. This paint was so thin it could not be isolated for pigment identification.

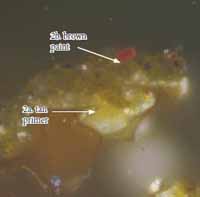

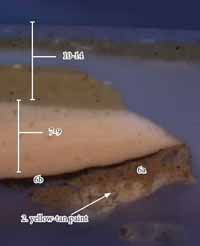

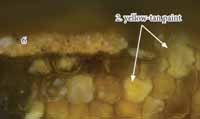

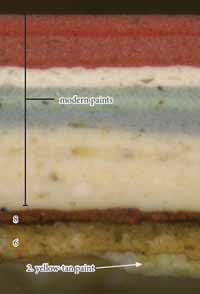

This was the earliest finish on the door architraves and leaves on the west wall, having been painted over a shellac sealant, and a yellowish-tan priming layer (generation 2a), made with yellow ochre, white lead, and some carbon black pigments. On the rest of the woodwork, it was simply painted over the extant coarsely-ground dark brown paint. Like the previous generation, the paint was coated with a thin layer of resinous varnish (generation 2c), which was not found in all samples, suggesting it was worn away.

Therefore, the results confirm that the door architraves and leaves on the west wall date to Period 2, c.1764, when the western wing was constructed. This evidence was found on the doorway to the southwest room (see samples NI 76 and 27, pp. 67-68), and the doorway to the northwest room (see samples NI 30 and 31, pp. 69-70). In addition, this provided a benchmark date for the second generation dark brown paint, and determined that approximately thirteen years had passed before the stair passage was re-painted.

Generations 3, 4:

During this period the stair passage was not repainted. By comparison, the southeast room was re-painted twice. The finishes appear to align in the next generation (generation 5), when the wainscot panelling was installed in both spaces.

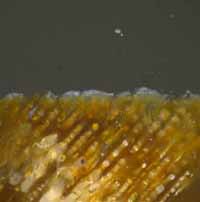

Generation 5: An exact date for this period is unknown, but it had to occur after 1764. During this period, all of the passage woodwork was again painted dark brown (generation 5b), this time with a paint containing approximately 1:1 carbon black and red iron earth pigments, all finely ground. This paint was also coated with a varnish (generation 5c), which in most samples was heavily worn, soiled, and disrupted, suggesting a long period of exposure. This was the earliest finish on all of the wainscot panelling, the closet in the northwest corner of the passage, and the baseboards. In fact, on these elements the fifth generation dark brown was painted over a gray primer (generation 5a).

Therefore, the results suggest that the wainscot, northwest closet, and baseboards were added in Period 3 (paint generation 5). This evidence was found on the wainscot below the stair stringer (see sample NI 7, p. 71), the wainscot along the stair (NI 11 and 16, pp. 72-73), and the wainscot on the west wall (NI 13 and 14, pp. 74-75). It was also found on the northwest closet paneling (NI 35, p. 76) the closet door leaf (NI 32, p. 77), and the baseboards throughout the room (NI 36, p. 78).

It would seem likely that the wainscot in the passage is contemporary with the wainscot in the first-floor southeast room, which was also first painted with a gray primer and a blue paint that was applied to the rest of the woodwork in the fifth generation. This would suggest that the southwest room was painted more frequently than the passage.

Paint generations one and two appear to have the same level of surface exposure and disruption. Knowing that generation one was exposed for thirteen years, it is possible that generation two was exposed for a 42 similar period of time. This is purely theoretical, but suggests that the fifth generation could date to c.1777. Interestingly, this is the year that Nicolson stopped taking in lodgers at his house (Samford, 1986), as it was no longer a financial necessity. Therefore, this upgrade could reflect Nicolson's desire to have the interior of his house to reflect his growing fortunes and rising social status.

After the fifth generation, the passage appears to have been unpainted for a long period of time. The varnish (generation 5c) is very soiled and disrupted, and deep cracks extend through the surface of the paint, and even into generations one and two. This could suggest that this finish was exposed to the end of Nicolson's residency (Nicolson passed away in 1797), and into the early 19th century, when the house passed from the Nicolson family to the Power family in 1803.

Binding media analysis was inconclusive regarding these early paints (pp. 21-23). However, visual analysis suggests they are traditional oil-bound paints (with the exception of generation 2, which appears to have a resinous binder).

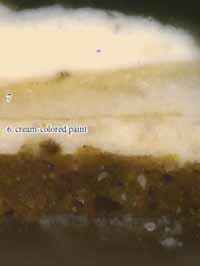

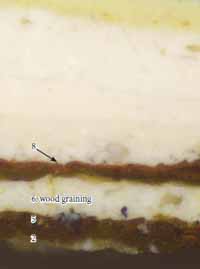

Generation six: This finish was found throughout the house, most notably as the sixth paint generation in the first-floor southwest room. Therefore, it is delineated generation six in all rooms. This scheme consisted of faux-wood grained door leaves, stairs, and baseboards, possibly in imitation of a light-colored wood, such as oak, with the architraves and wainscot painted a cream color. The wainscot caps, stair handrails and newel posts appear to have been grain-painted to imitate a more orange-red-colored wood. This scheme is consistent with an early 19th-century date, and most likely reflects the period of the Power occupancy (1803 - c.1840).

Generation seven: This scheme consists of a finely ground, resinous grayish-colored paint on the staircase and wainscot. This paint has a bright bluish, twinkling autofluorescence characteristic of zinc white (ZnO), a pigment that was not commercially available in housepaints until c.1845. During this same period, the door leaves and architraves were painted dark brown with a resinous paint.

Generation eight: The scheme during this period is unclear. A thin layer of brick-red colored paint was found on a few elements (cellar door leaf and architrave, north entrance door leaf, closet leaf, door leaf to the northwest room), but in all other samples there was only a white paint.

Generations 9-11: These paints are all finely ground, smooth, and consistent white paints that appear to have been industrially prepared, and probably date to the late 19th or early 20th century.

Generations 12-15: These are yellow-ochre colored paints, the earliest of which probably dates to 1940, when Cogar restored the house. Cogar noted in his diary that rudimentary paint scrapes carried out by himself and his mother found that the first paint in the passage was yellow. It seems likely that these scrapes were carried out on one of the doorways on the west wall, where the wood was first painted with a yellow-tan primer (generation 2a).

Generations 16-18: These represent the present pale blue, or 'pearl' colored paints in the passage.

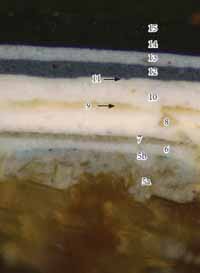

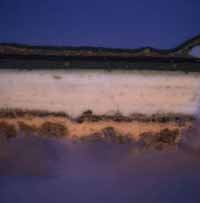

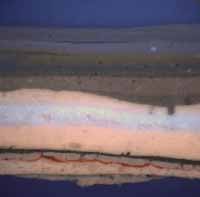

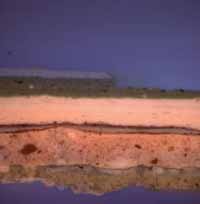

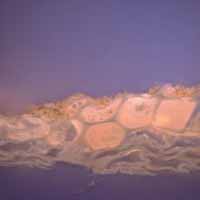

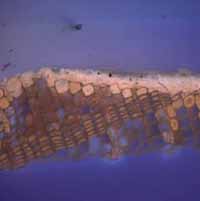

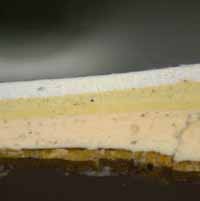

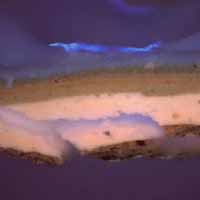

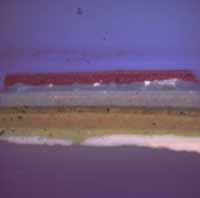

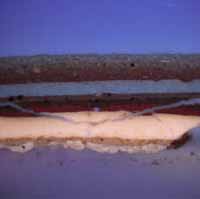

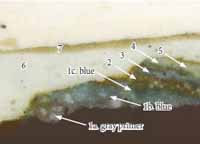

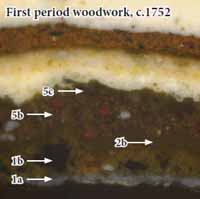

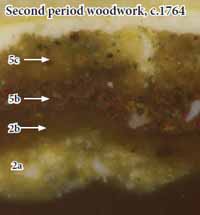

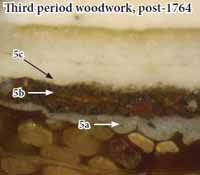

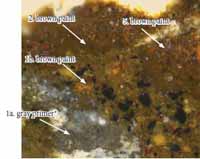

Comparison of Stair Passage samples showing three phases of construction

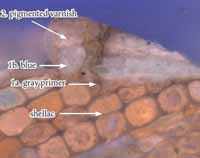

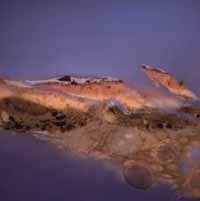

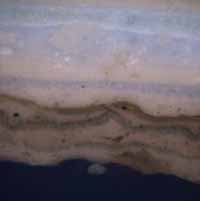

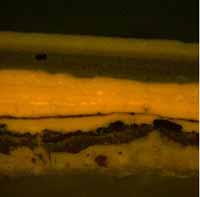

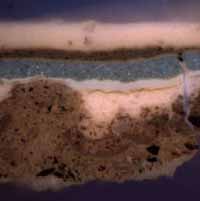

NI 39, visible light, 200x (cellar door leaf)

NI 39, visible light, 200x (cellar door leaf)

First period woodwork — cellar door leaf and architraves on the east side, and the stair.

Gray primer (1a), with coarsely ground dark brown paint (1b) and varnish (1c).

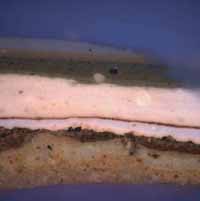

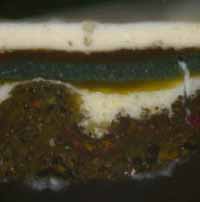

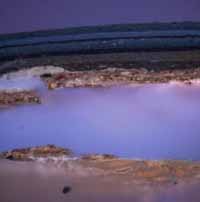

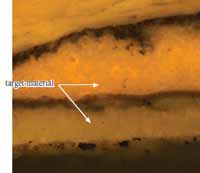

NI 30a, visible light, 200x (door architrave to NW room)

NI 30a, visible light, 200x (door architrave to NW room)

Second period woodwork — door leaves and architraves on the west side.

Yellow-tan primer (2a), with finely ground dark brown paint (2b) and varnish (2c).

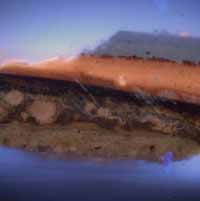

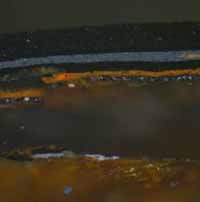

NI 13a, visible light, 200x (wainscot on west wall)

NI 13a, visible light, 200x (wainscot on west wall)

Third period woodwork — all wainscot panelling, including those below the stair stringer. Also closet and closet panelling in NW corner

Gray primer (5a), and finely ground dark brown paint (5b) and varnish (5c).

| Paint Generation | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 16-18 | pale blue paints, modern | current finish |

| 13-15 | deep yellow paint, modern | |

| 12 | deep yellow paint, modern | possibly Cogar-era (1940) |

| 9-11 | white paint, post-industrial | late 19th or early 20th c. |

| 8 | inconclusive, some samples have brick-red paint, but most have white paints | |

| 7 | gray paint on staircase and wainscot, dark brown resinous paint on door leaves and architraves | gray paint contains zinc white (ZnO), post c.1845 |

| 6 | faux wood graining (6a-6d), possibly oak, on staircase, door leaves, and wainscot caps. Cream-colored paint on rest of woodwork. | Same scheme in other first-floor rooms. |

| 5 c.1777(?) | gray primer (3a), finely ground dark brown paint made with red and black particles (3b), varnish (3c) | first generation on all wainscot panelling, closet in NW corner, and baseboards. Aligns with new woodwork in adjacent southeast room |

| 4 | — | not repainted |

| 3 | — | not repainted |

| 2 c.1764 | yellow-tan primer (2a), finely ground dark brown paint with dim autofluorescence (2b), varnish (2c) | first generation on door leaves and architraves on west wall |

| 1 c.1752 | gray primer (1a), coarsely ground dark brown paint (1b), varnish (1c) | found on staircase, all door leaves and architraves except for those on the west wall |

First-Floor Stair Passage [Room 105] — Sample Location Photos

overall view, facing southeast

overall view, facing southeast

12th full baluster from first floor

12th full baluster from first floor

17th full baluster from first floor

17th full baluster from first floor

wainscot along east side of stair

wainscot along east side of stair

horizontal architrave in stairwell

horizontal architrave in stairwell

doorway to SE room, right architrave

doorway to SE room, right architrave

south entrance door (blocked by heavy furniture)

south entrance door (blocked by heavy furniture)

south entrance door (blocked by heavy furniture)

south entrance door (blocked by heavy furniture)

west wall, wainscot cap left of SW room

west wall, wainscot cap left of SW room

closet at NW corner of passage

closet at NW corner of passage

baseboard on west wall, right of NW room

baseboard on west wall, right of NW room

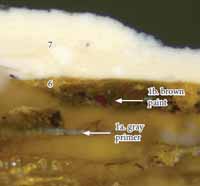

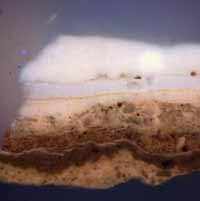

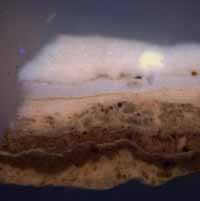

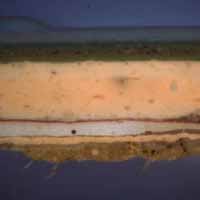

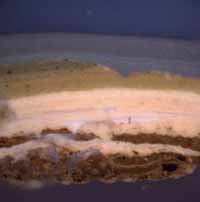

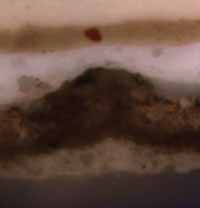

Sample NI 39: Door leaf to cellar stair, bottom ovolo of lock rail

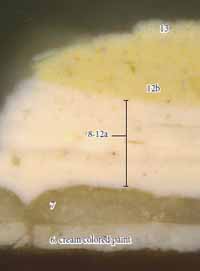

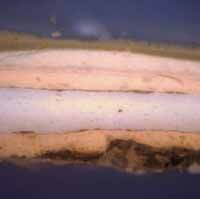

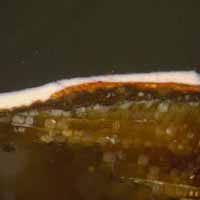

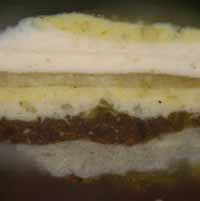

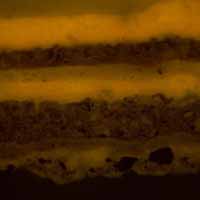

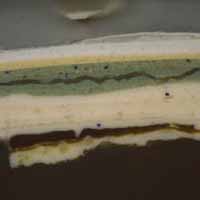

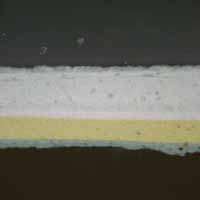

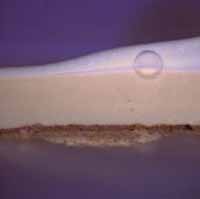

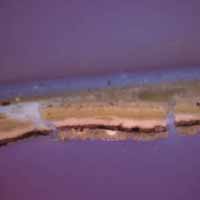

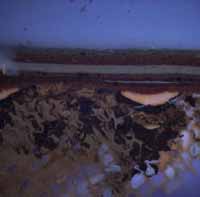

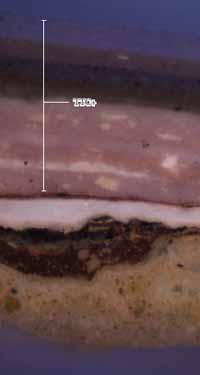

This sample from the cellar door leaf has the most intact early stratigraphy from all samples taken from the stair passage. It clearly shows the first generation gray primer (1a) and dark brown paint (1b), which contains very large orange and black pigment particles. In this sample, a very thin varnish (1c) over the surface of the first generation is visible. The second generation brown paint is much more finely ground and has a very dim autofluorescence, which strongly differentiates it from generations one and two. The passage was unpainted in generations 3 and 4. This was determined through comparison of samples from the adjacent southeast room.

Generation five is a finely ground brown paint composed of red and black particles. There is a varnish layer (5b) over this paint that in most samples is soiled and disrupted, suggesting a long period of exposure. The next generation is a faux-wood graining finish, which was used throughout the house, usually on the door leaves and wainscot caps.

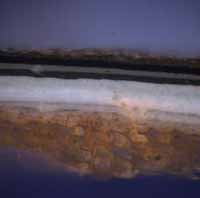

Sample NI 40: Door architrave to cellar stair, fillet of east architrave, inner edge

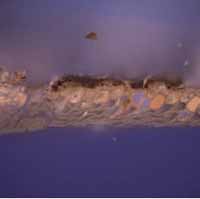

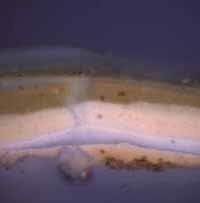

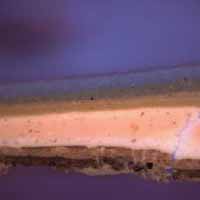

NI 40a (repolished), visible light, 400x

NI 40a (repolished), visible light, 400x

NI 40a (repolished), UV light, 400x

NI 40a (repolished), UV light, 400x

The door architrave to the cellar stair also contains the first three generations of dark brown paints (generations 1, 2, and 5), indicating that this element is first period.

Sample NI 9: stair handrail, west face, above 9th baluster, middle of thin astrigal

The samples from the stair handrails were more fragmented, but were found to contain all three early dark brown paints, indicating that these elements are first period. Sample NI 9 represents all handrail samples.

Sample NI 2: stair, 17th baluster from first floor, northeast edge of ovolo below upper square

The samples from the stair balusters were also fragmented, but contained all three early dark brown paints, indicating that these elements are first period. Sample NI 2 represents all baluster samples.

Sample NI 15: stair, second newel post, top of first stair run, east face

The sample from the newel contained all three early dark brown paints, indicating that this element is first period. Sample NI 15 represents all newel samples.

Sample NI 18: horizontal north-facing architrave finishing the south edge of the stairwell adjacent to east plaster wall (transverse partition)

The sample from the stair architrave contained all three early dark brown paints, indicating that this element is first period.

Interestingly, this element is adjacent to the wall, and the sample does appear to contain what could be wall-related finishes, between generations 1 and 2, and between generations 2 and 5. The sample was stained with fluorochromes to characterize these materials (see p. 82), but the results were inconclusive.

Sample NI 3: outer stair stringer below 11th and 12th balusters, top of cove

The samples from the stair stringers are fragmented, but contained all three early dark brown paints, indicating that this elements are first period. Sample NI 3 represents all stringer samples.

Sample NI 80: north door leaf, second rail from top, bottom ovolo

The samples from the north entrance door leaf contained all three early dark brown paints, indicating that this element is first period. Sample NI 80 represents all north wall door leaf samples.

Sample NI 81: north door architrave, left (west) side), inner bead

Like its corresponding leaf (previous page), the north entrance door architrave also contained all three early dark brown paints, indicating that this element is first period. However, the right (east) jamb of this architrave appears to have been re-used from another room. See next page.

Sample NI 83: north door architrave, right (east) side, backband fillet

Interestingly, the right (east) jamb of the north entrance door architrave appears to have been re-used from another room, possibly the first-floor northeast room (present kitchen), where the woodwork contains the same paint history of early blues.

Sample NI 75: door architrave to northeast room (kitchen), north side, center fascia

The sample from the door architrave to the northeast room (present kitchen) contained all three early dark brown paints, indicating that this element is first period.

Sample NI 22: door leaf to southeast room, beveled edge of lower left raised panel

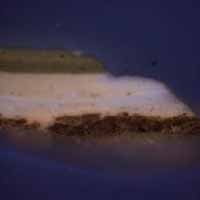

NI 22a, visible light, 400x (lightened in PS)

NI 22a, visible light, 400x (lightened in PS)

The sample from the door leaf to the southeast room contained all three early dark brown paints, indicating that this element is first period.

Sample NI 20: door architrave to southeast room, center fascia

Although fragmented, the sample from the door architrave to the southeast room contained the first generation gray primer and dark brown paint, indicating that this element is first period. Generation two is missing from this sample, but generation three is present.

Sample NI 78: south (front) door architrave, east side, backband fillet

The sample from the door architrave to the south entrance contained the first three generations of dark brown paint, indicating that this element is first period.

Sample NI 79: south (front) door leaf, east leaf, top rail, bottom ovolo

The sample from the south entrance door leaf contained the first three generations of dark brown paint, indicating that this element is first period.

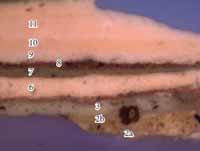

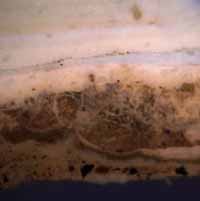

Sample NI 76: door architrave to southwest room, cyma of top architrave

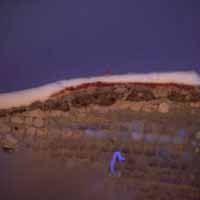

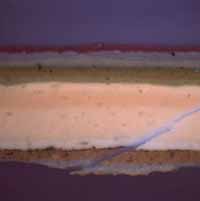

NI 76, visible light, 400x (early layers only)

NI 76, visible light, 400x (early layers only)

NI 76, UV light, 400x (early layers only)

NI 76, UV light, 400x (early layers only)

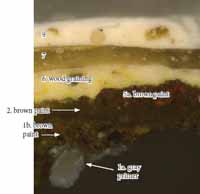

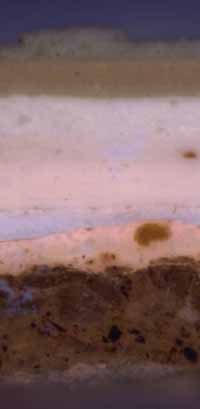

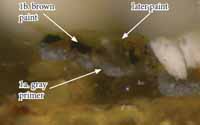

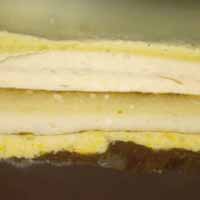

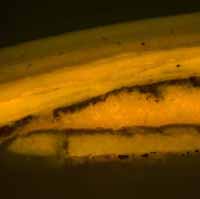

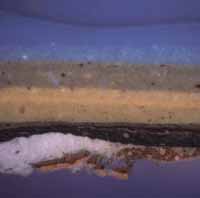

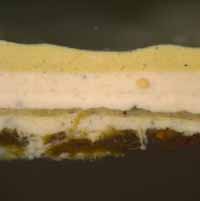

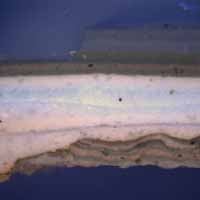

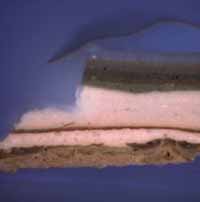

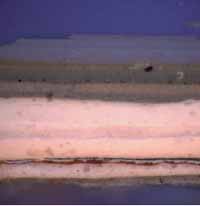

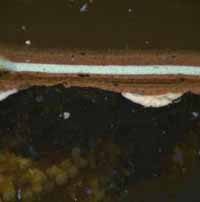

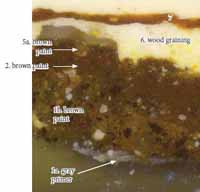

As expected, the sample from the door architrave to the SW room is missing the first generation gray primer and dark brown paint, confirming that this woodwork is later. The earliest finish is a yellowish-tan primer (2a), followed by the second generation finely ground dark brown paint (2b) that has a dark autofluorescence in reflected UV light.

This evidence confirms this architrave was installed in Period 2 (c.1764).

Sample NI 27: door leaf to southwest room, bottom ovolo of bottom right panel

The sample from the door leaf to the SW room is disrupted, but a fragment of the second generation dark brown paint is attached to the bottom of the sample. This would indicate that this leaf is also second period, like its corresponding architrave (see previous page).

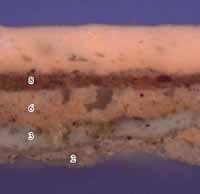

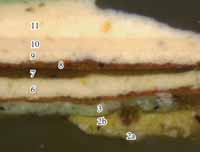

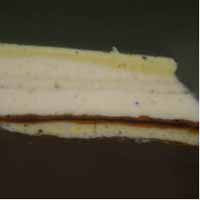

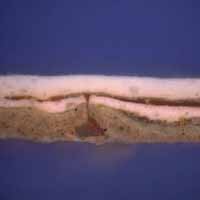

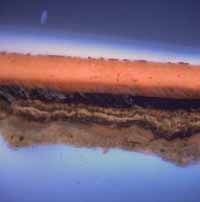

Sample NI 31: door leaf to northwest room, bottom right panel, right beveled edge

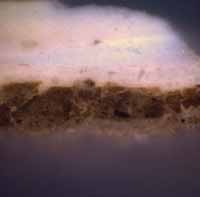

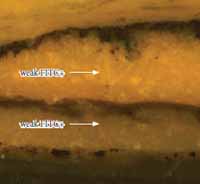

NI 31a (repolished), visible light, 400x (lightened in PS)

NI 31a (repolished), visible light, 400x (lightened in PS)

NI 31a (repolished), UV light, 400x (lightened in PS)

NI 31a (repolished), UV light, 400x (lightened in PS)

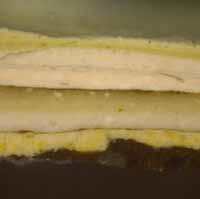

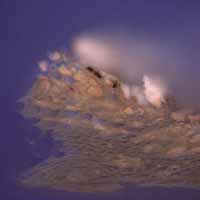

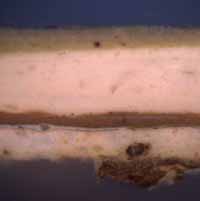

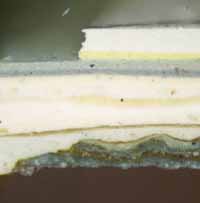

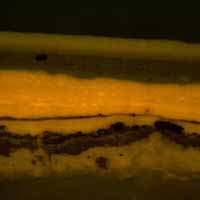

The sample from the door leaf to the NW room begins with the second generation yellow-tan primer (2a), followed by the finely ground dark brown paint (2b), and varnish (2c).

This evidence confirms this architrave was installed in Period 2 (c.1764).

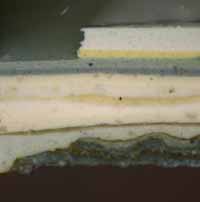

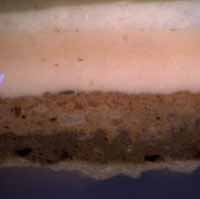

Sample NI 30: door architrave to northwest room, right architrave, middle fascia

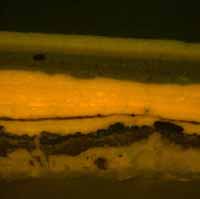

Like its corresponding door leaf (previous page), the sample from the door architrave to the NW room begins with the second generation yellow-tan primer (2a), followed by the finely ground dark brown paint (2b), and varnish (2c).

This evidence confirms this architrave was installed in Period 2 (c.1764).

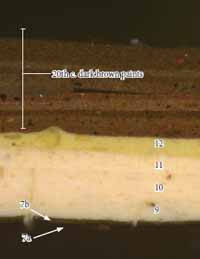

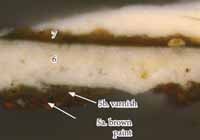

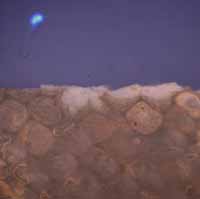

Sample NI 7: paneling below stair stringer, rail

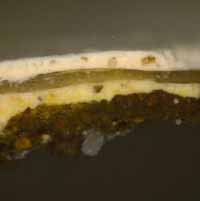

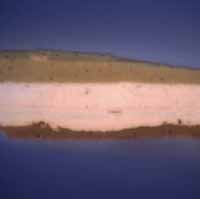

All of the samples from the wainscot panelling below the stair stringer had the same stratigraphy. Sample NI 7, shown above, represents the group. Generations one and two are missing, and the earliest paint is a gray primer (5a) and the fifth generation dark brown paint (3b), which contains finely ground red and black pigment particles (remember the passage was unpainted in generations 3 and 4).

The absence of generations one and two suggest that this panelling is later, post-dating even the west addition, c.1764.

Sample NI 11: upper rail of wainscot rising along east side of stair

The wainscot on the east side of the stair has the same stratigraphy as the rest of the wainscot panelling in this space. Generations one and two are missing, and the earliest paint is a gray primer (5a) and the fifth generation dark brown paint (5b), which contains finely ground red and black pigment particles.

The absence of generations one and two suggest that this panelling is later, post-dating even the west addition, c.1764.

Sample NI 16: wainscot at stair landing, ovolo of stile east of middle panel

The wainscot on the stair landing has the same stratigraphy as the rest of the wainscot panelling in this space. Generations one and two are missing, and the earliest paint is a gray primer (5a) and the fifth generation dark brown paint (5b), which contains finely ground red and black pigment particles.

The absence of generations one and two suggest that this panelling is later, post-dating even the west addition, c.1764.

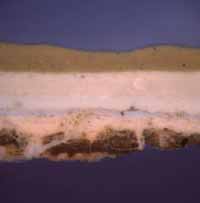

Sample NI 13: west wall, wainscot stile to right of door to southwest room

The wainscot on the west wall has the same stratigraphy as the rest of the wainscot panelling in this space. Generations one and two are missing, and the earliest paint is a gray primer (5a) and the fifth generation dark brown paint (5b), which contains finely ground red and black pigment particles.

The absence of generations one and two suggest that this panelling is later, post-dating even the west addition, c.1764.

Sample NI 14: west wall, cap of wainscot to right of door to southwest room (above NI 13)

Sample NI 14 is shown here to illustrate that in generation six, when the panelling and architraves were painted a cream color, and the door leaves and stair balusters were painted to imitate a light-colored wood (possibly oak), the cap of the wainscot (as well as the stair handrails) were painted to imitate a more orange-red colored wood.

Sample NI 35: paneling on east side of closet at northwest end of passage, ovolo of stile

The closet in the northwest corner has the same stratigraphy as the rest of the wainscot panelling in this space. Generations one and two are missing, and the earliest paint is a gray primer (5a) and the fifth generation dark brown paint (5b), which contains finely ground red and black pigment particles. The absence of generations one and two suggest that this panelling is later, post-dating even the west addition, c.1764.

Sample NI 32: upper door of closet at northwest end of passage, lower bevel of bottom panel

The closet doors have the same stratigraphy as the rest of the wainscot panelling, post-dating even the west addition, c.1764.

Sample NI 36: baseboard on west wall, cyma cap, adjacent to door to northwest room

Multiple samples were taken from the baseboards in the stair passage, and all appeared to begin with the fifth generation gray primer (5a) and dark brown paint (5b), which suggests they are contemporary with the wainscot panelling. Sample NI 36, taken from the west wall, is representative for the group.

According to this sample, the baseboards were also faux-wood grained in generation six, along with the door leaves and the staircase. In generation seven, the baseboards were painted with a resinous gray paint. In generations 8-11, the baseboards were painted white along with the rest of the woodwork.

Sample NI 39: Door leaf to cellar stair, bottom ovolo of lock rail

TTC stain for carbohydrates (starches, gums, cellulosic fillers)

NI 39, UV light, 400x. Before TTC stain.

NI 39, UV light, 400x. Before TTC stain.

NI 39, UV light, 400x. TTC reaction.

NI 39, UV light, 400x. TTC reaction.

Sample NI 39 was stained with TTC to tag carbohydrates in the stratigraphy.

Positive reactions (a dark red-brown color) were observed in generations eight and nine (modern paints not photographed).

No reactions were observed in the earliest generations.

Sample NI 18: Horizontal, north-facing architrave finishing the south edge of the stairwell

FITC stain for proteins (animal glue, casein)

NI 18, B-2A filter, 200x. Before FITC stain.

NI 18, B-2A filter, 200x. Before FITC stain.

NI 18, B-2A filter, 200x. TTC reaction.

NI 18, B-2A filter, 200x. TTC reaction.

Sample NI 18 was stained to characterize the autofluorescent materials between the paint layers. There was no reaction with TTC. There was a very weak reaction for proteins with FITC, but it was not strong enough to be conclusive. The material did not appear to be oil-based, so it was not stained with DCF. The nature of these materials is still unclear.

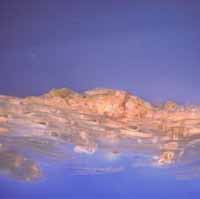

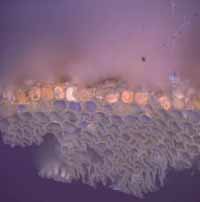

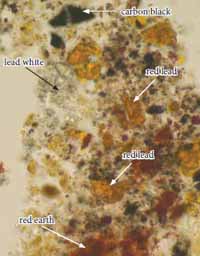

Pigment ID: first generation gray primer

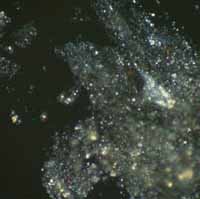

NI 39, dispersed pigments from first generation gray primer, plane polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, dispersed pigments from first generation gray primer, plane polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, dispersed pigments from first generation gray primer, cross polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, dispersed pigments from first generation gray primer, cross polarized light, 1000x

The first generation gray primer (generation 1a), is comprised of mostly lead white pigment (2PbCO3 ⋅ Pb(OH)2), visible as very small, rounded transparent particles with high relief and a bright birefringence in crossed polars. A good amount of chalk (CaCO3) was also present, a commonly used inert extender in housepaints. The chalk particles are large, flat plate-shaped particles with an undulose birefringence.

Some carbon black particles were also seen, which were black and opaque in transmitted light, and dark under crossed polars. Most particles were very fine and well dispersed throughout the medium, although occasional large carbon black particles were also found.

A few agglomerations of golden-brown-colored particles were present, which are dark under crossed polars. These could be some type of earth pigment — possibly a yellow ochre, a sienna, or an umber. The exact type of pigment could not be determined.

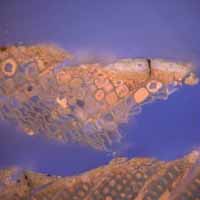

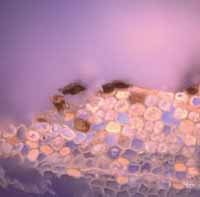

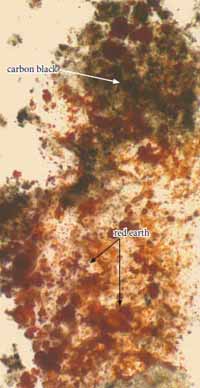

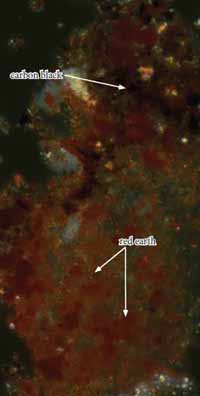

Pigment ID: first generation dark brown paint

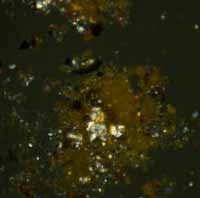

NI 39, dispersed pigments from first generation brown paint, plane polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, dispersed pigments from first generation brown paint, plane polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, UV light, 400x, dispersed pigments from first generation brown paint, cross polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, UV light, 400x, dispersed pigments from first generation brown paint, cross polarized light, 1000x

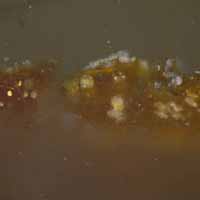

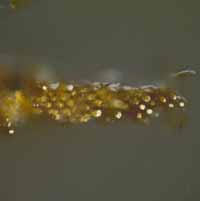

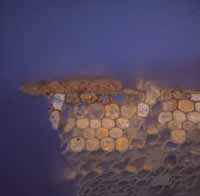

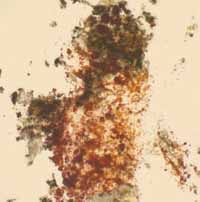

In cross-section, the first generation dark brown paint is very coarsely ground and contains large black, yellow, and red-colored pigment particles, which are much more apparent in the dispersed sample (photomicrographs from this paint continue on the next page). PLM suggests that this paint contains approximately 1/3 carbon black, 1/3 yellow and red earth pigments, and 1/3 red lead pigments. Some lead white pigments were also visible.

The carbon black pigments are the most apparent in this sample, visible in a range of particle sizes from very fine to very large. All are flat and opaque with sharp edges, suggestive of a coarsely ground charcoal black.

Yellow, red, and brown (sienna, umber) earth pigments are visible as clumps of golden-yellow, red, an brown particles of varying shape and size, from small grains to large agglomerations with amorphous boundaries. These pigment are isotropic in crossed-polars, although some golden and deep red birefringence was observed where particles were clumped together (an occasional "ruby-red" color in transmitted light is recorded for iron oxide red in Gettens and Stout, 122).

Pigment ID: first generation dark brown paint

NI 39, dispersed pigments from first generation brown paint, plane polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, dispersed pigments from first generation brown paint, plane polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, UV light, 400x, dispersed pigments from first generation brown paint, cross polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, UV light, 400x, dispersed pigments from first generation brown paint, cross polarized light, 1000x

Red Lead reference, plane polarized light, 1000x

Red Lead reference, plane polarized light, 1000x

Red Lead reference, cross polarized light, 1000x (note blue-green interference colors)

Red Lead reference, cross polarized light, 1000x (note blue-green interference colors)

The sample also contained a large amount of red lead particles (Pb3O4), visible as coarse orange-colored particles with high relief that display bright blue-green interference colors under crossed polars, which is diagnostic for red lead pigment (see comparison to reference sample below).

Some lead white particles were also found in the sample, but could originate from the gray primer below. Other colorless particles that were present in the sample could represent mineral inclusions associated with earth pigments, such as calcite, quartz, or clays.

Pigment ID: second generation yellow-tan primer on west wall doors and architraves

NI 31, dispersed pigments from second generation yellow-tan primer, plane polarized light, 1000x

NI 31, dispersed pigments from second generation yellow-tan primer, plane polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, UV light, 400x, dispersed pigments from second generation yellow-tan primer, cross polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, UV light, 400x, dispersed pigments from second generation yellow-tan primer, cross polarized light, 1000x

The second generation yellow-tan primer (generation 2a), is comprised of approximately 1:1 lead white pigment (2PbCO3 ⋅ Pb(OH)2), and yellow earth pigment. The lead white pigments are very small, rounded transparent particles with high relief and a bright birefringence in crossed polars. The yellow earth pigments are golden-yellow to brownish-yellow rounded particles of varying size that are dark under crossed-polars.

Some very fine carbon black particles were also seen, which were black and opaque in transmitted light, and dark under crossed polars. Most particles were very fine and well dispersed throughout the medium, although occasionally, larger carbon black particles were also found.

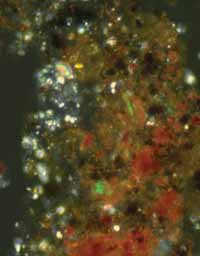

Pigment ID: fifth generation dark brown paint

NI 39, dispersed pigments from third generation brown paint, plane polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, dispersed pigments from third generation brown paint, plane polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, UV light, 400x, dispersed pigments from third generation brown paint, cross polarized light, 1000x

NI 39, UV light, 400x, dispersed pigments from third generation brown paint, cross polarized light, 1000x

The fifth generation dark brown paint is composed of approximately ½ carbon black and ½ red earth pigments, which are more finely ground than the pigments in generation 1.

Carbon black is visible as opaque black particles that have sharp edges and are isotropic in crossed polars.

Red earth pigment particles are visible as rounded red to orange-red particles (and agglomerations of particles), with broad particle size distribution. The particles are isotropic but some have a deep red color in crossed polars.

First-Floor Stair Passage [Room 105] - Colorimetry

Generation 1a: gray primer in stair passage and first-floor southeast room

Sample NI 39 (stair passage, door leaf to cellar), uncast, 200x

Sample NI 39 (stair passage, door leaf to cellar), uncast, 200x

Sample NI 43 (first-floor southeast room, door leaf), uncast, 200x

Sample NI 43 (first-floor southeast room, door leaf), uncast, 200x

Accurate color readings for the first generation gray primer used in the stair passage and the southeast room could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter because this layer was very thin and a clean, intact area could not be isolated for measurement. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest match for the gray primer was determined to be Benjamin Moore 2134-30 "Iron Mountain".

Benjamin Moore

Benjamin Moore

2134-30

"Iron Mountain"

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 36.27 | +0.10 | +1.09 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 2.3Y | 3.5 | 0.1 |

Generations 1, 2, and 5 in stair passage: dark brown paint

Sample NI 39 (door leaf to cellar), uncast, 200x

Sample NI 39 (door leaf to cellar), uncast, 200x

Generations 1, 2, and 5 in the stair passage are all dark brown paints of an extremely similar color, although they have very different textures and consistencies which helped identify them in cross-section. Accurate color readings for these paints could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter because a clean, intact area could not be isolated for measurement. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest match was determined to be Benjamin Moore/Colonial Williamsburg Color CW-170 "Tarpley Brown".

This swatch was the closest color match to all three dark brown paint generations in the stair passage.

Colonial Williamsburg

Colonial Williamsburg

#170

"Tarpley Brown"

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26.49 | +5.14 | +6.91 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 4.3YR | 2.5 | 1.4 |

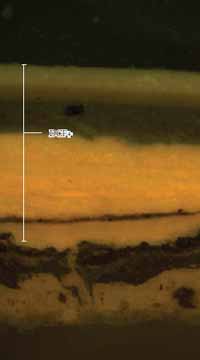

Generation 2 yellow-tan primer on west wall doors and architraves (c.1764); also used as finish coat in second-floor western spaces

NI 30a, visible light, 200x (door architrave to NW room)

NI 30a, visible light, 200x (door architrave to NW room)

Accurate color readings for the yellow-tan primer/finish coat could not be obtained with the Minolta Chroma Meter because it was very fragmented and a clean, intact area could not be isolated for measurement. Instead, the closest commercial color match was determined by eye using a stereomicroscope at 30x magnification with a color corrected light source. The closest match was determined to be Benjamin Moore HC-17 "Summerdale Gold".

Benjamin Moore

Benjamin Moore

HC-17

"Summerdale Gold"

| CIE L*a*b* values | L* (black to white) | a* (green to red) | b* (blue to yellow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 68.92 | -1.03 | +32.08 | |

| Munsell values | hue | value | chroma |

| 4.0Y | 6.8 | 4.6 |

First-Floor Southwest Room [Room 102]

First floor plan, Robert Nicolson House Southwest room is outlined in red

First floor plan, Robert Nicolson House Southwest room is outlined in red

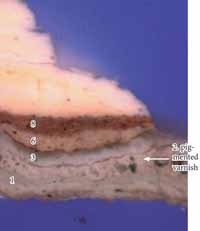

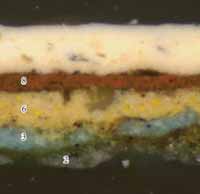

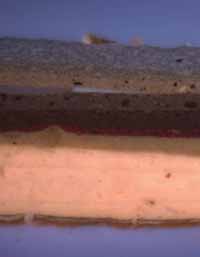

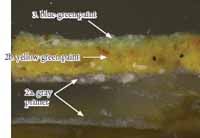

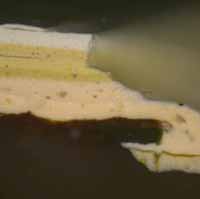

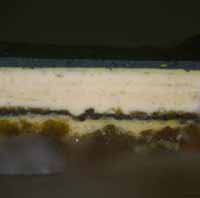

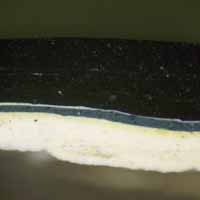

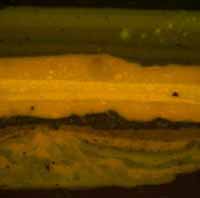

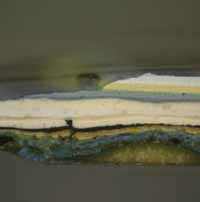

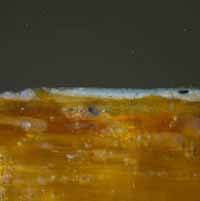

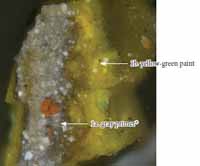

Discussion of results: This study found that the woodwork in the first-floor southwest room retains excellent, intact paint evidence that elucidates the decorative and structural history of this room. Since this west wing of the house was constructed c.1764, the earliest paint is this room is labelled generation 2.

Interestingly, in contrast to the stair passage and the first-floor southeast room, the paint analysis results suggest that the wainscot in this room (and the adjacent northwest room) was not added later, but is contemporary with the rest of the second-period woodwork.

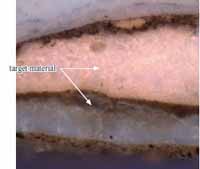

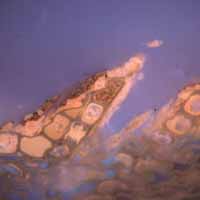

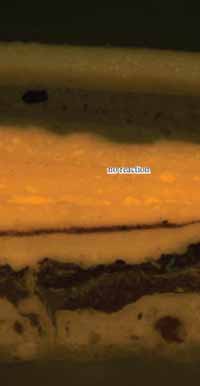

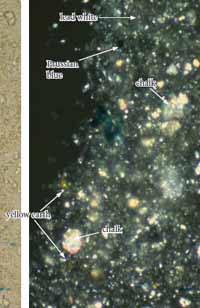

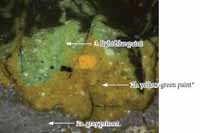

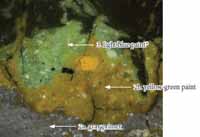

Generation 2: This generation consists of a shellac sealant (identified by its orange autofluorescence) followed by a coarsely ground gray primer that contains lead white, carbon black, and a few scattered, large red earth pigment particles. This was finished with a coarsely ground yellow-green paint that contains white lead, yellow earth pigments, and small amounts of Prussian blue and carbon black. In a few samples (NI 48, p. 98 and NI 51, p. 96) there was a thin layer of grime on the surface of this paint, suggesting it was exposed for a relatively long period of time.

This finish was found on all woodwork in the room, including the mantel (NI 52 and 53, pp. 94-95), the door architrave and leaf to the passage (NI 50, p. 97), and the wainscot panels (NI 48 and 55, p. 98). Therefore, the wainscot in this room is contemporary with the rest of the woodwork and would date to c.1764, unlike the passage and east rooms, where it was added c.1777.

Generation 3: This generation consists of a coarsely ground blue-green paint made with lead white, yellow earth, and large particles of Prussian blue pigment. There is a thin, brownish layer on the surface of this paint that could be grime or an oil-based varnish (based on its dim autofluorescence in UV).

Generations 4-5: During these periods, the mantel was painted black and varnished. The rest of the woodwork appears to have been unpainted.

Binding media analysis determined there were no proteins or carbohydrates in these early paints. There was a very weak positive reaction for oils (DCF+), confirming the visual analysis that these are traditional oilbound finishes (p. 99-101).

Generation 6: This generation is the same scheme of cream-colored woodwork and faux-grained doors

92Generation eight: The scheme during this period is unclear. A thin layer of brick-red colored paint was found on the mantel, but in all other samples there was only a white paint.

Generations 9-12: These paints are all finely ground, smooth, and consistent white paints that appear to have been industrially prepared, and probably date to the late 19th or early 20th century.

Generations 13-17: These are modern paints, including the present pale blue color. Generation 13 is the first of three green-colored paints, which probably dates to 1940, when Cogar restored the house. Cogar noted in his diary that rudimentary paint scrapes carried out by himself and his mother found that the first paint in this room was green (Wenger 1986, 28).

| Paint Generation | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | pale blue paint, modern | current finish |

| 16 | deep yellow paint, modern | |

| 13-15 | green paints, modern | possibly Cogar-era (1940) |

| 9-12 | white paint, post-industrial | late 19th or early 20th c. |

| 8 | inconclusive, some samples have brick-red paint, but most have white paints | |

| 7 | gray paint on mantel and wainscot, dark brown resinous paint on door leaves and architraves | gray paint contains zinc white (ZnO), post c.1845 |

| 6 | faux wood graining (6a-6d), possibly oak, on door leaves, rest of woodwork painted cream. Mantel painted black and varnished. | |

| Same scheme in other first-floor rooms. | ||

| 5 | mantel painted black (5a) and varnished (5b) | |

| 4 | mantel painted black (4a) and varnished (4b) | |

| 3 post-1764 | blue-green paint (3a), grime or oil-based varnish (3b) | |

| 2 c.1764 | gray primer (2a), yellow-green paint (2b) | found on all woodwork, including wainscot |

| 1 c.1752 | not yet constructed |

First-Floor Southwest Room [Room 102] - Sample Location Photos

Sample NI 52: Mantel, cushion of crown molding above dentil course, far left end

Sample NI 53: Mantel, backboard, far left end, near top

Sample NI 51: door architrave on east wall, right (south) architrave, backband cyma

The other sample from the inner fascia of this same architrave (NI 47), has the same early paints as the sample above. Therefore, the entire architrave is of the same period.

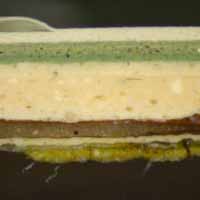

Sample NI 50: door leaf to passage (east wall), center left panel, ovolo on underside

Sample 50b (above) is shown to illustrate the complete stratigraphy for the room.

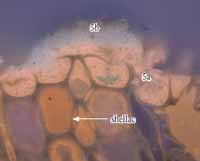

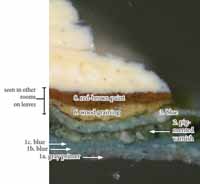

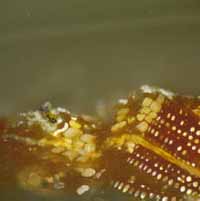

NI 49a, visible light, 400x (taken from same door, but raised panel)

NI 49a, visible light, 400x (taken from same door, but raised panel)

NI 49a, UV light, 400x (taken from same door, but raised panel)

NI 49a, UV light, 400x (taken from same door, but raised panel)

Sample NI 55: wainscot stile, north wall, immediately adjacent to mantel

Sample NI 52: Mantel, cushion of crown molding above dentil course, far left end

TTC stain for carbohydrates (starches, gums, cellulosic fillers)

NI 52, UV light, 200x. Before TTC stain.

NI 52, UV light, 200x. Before TTC stain.

NI 52, UV light, 200x. TTC reaction.

NI 52, UV light, 200x. TTC reaction.

Sample NI 52 was stained with TTC to tag carbohydrates in the stratigraphy.

Positive reactions (a dark red-brown color) were observed in generations 9-17, which probably result from cellulosic fillers in modern paints.

No reactions were observed in the earliest generations.

FITC stain for proteins (animal glues, casein)

NI 52, B-2A filter, 200x. Before FITC stain.

NI 52, B-2A filter, 200x. Before FITC stain.

NI 52, B-2A filter, 200x. FITC reaction.

NI 52, B-2A filter, 200x. FITC reaction.

Sample NI 52 was repolished and stained with FITC to tag proteins in the stratigraphy.

No positive reactions (a yellow-green fluorescence) were observed.

DCF for lipids (oils)

NI 52, B-2A filter, 200x. Before DCF stain.

NI 52, B-2A filter, 200x. Before DCF stain.

NI 52, B-2A filter, 200x. DCF reaction.

NI 52, B-2A filter, 200x. DCF reaction.

Sample NI 52 was repolished and stained with DCF to tag oils in the stratigraphy.

Positive reactions (a yellow-green fluorescence) were observed in the modern paints (generations 7-17). There was a very weak reaction in the earliest paints, which may not be visible in the printed image.

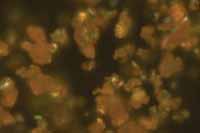

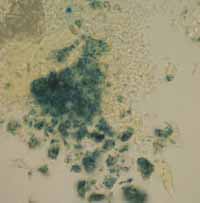

Pigment ID: second generation gray paint

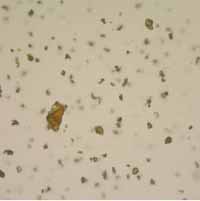

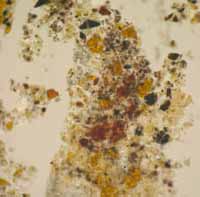

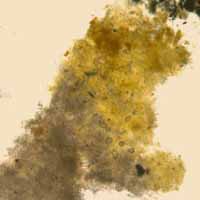

dispersed pigment sample from second generation gray paint, sample NI 52 (mantel), plane polarized light, 1000x

dispersed pigment sample from second generation gray paint, sample NI 52 (mantel), plane polarized light, 1000x

dispersed pigment sample from second generation gray paint, sample NI 52 (mantel), cross polarized light, 1000x

dispersed pigment sample from second generation gray paint, sample NI 52 (mantel), cross polarized light, 1000x

The second generation gray primer in the first floor southwest room is comprised of mostly lead white pigment (2PbCO3 ⋅ Pb(OH)2), visible as very small, rounded transparent particles with a bright birefringence in crossed polars. Dispersed throughout the lead white are fine particles of carbon black pigments, which are black and opaque in transmitted light, and dark under crossed polars.

Some red earth pigments were also identified, having a deep red color, rounded edges and existing in a range of sizes. These particles are isotropic but have a reddish color in cross-polarized light. Some smaller particles of yellow earth were also seen, having a yellow color in transmitted light and isotropic under crossed polars.