The New Architecture of Merchants Square

text by Edward Chappell

photos by Barbara Lombardi

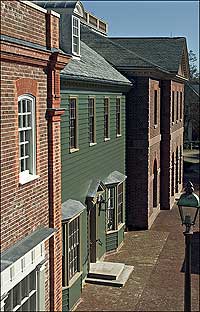

Facing Boundary Street, a simple weatherboarded shop flanked by bolder, formal corner edifices on the north and south.

The north alley face, above, and east alley, right, are simple versions of their more elaborate fronts.

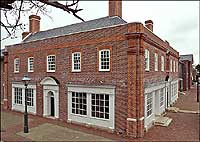

The south structure.

This structure stands at the ancient intersection of Duke of Gloucester Street, Boundary Street, Richmond Road, and Jamestown Road. The project's most formal edifice, it turns nearly identical facades south and west. Its sources include Mount Airy on Virginia's Northern Neck and Blandfield across the Rappahannock River near Tappahannock.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's commitment to excellence in a shopping area it built for businesses displaced by the restoration of the eighteenth-century city—Merchants Square—is reflected by a remarkable addition that opened this spring. It is a group of structures in what is really a single edifice, unofficially known as the College Corner Building for its proximity to the triangular intersection of Jamestown and Richmond Roads at the apex of the College of William and Mary's three-centuries-old campus. English architect Quinlan Terry began the design in 2000, and working with the foundation's architectural historians, created elevations surprising as well as familiar, which look as though they belong in Merchants Square, without repeating well-known, well-loved details seen along Williamsburg's streets.

Merchants Square architecture has always been eclectic and playful compared to the heart of the restoration, the Historic Area. Terry responded to this tradition, drawing inspiration from English and Virginia structures. He is especially attracted to such expressive eighteenth-century Tidewater houses as Rosewell on the York River and Mount Airy on the Rappahannock. Some of the 1760s stonework at Mount Airy can be seen at the southwest corner, though he varied the sizes of the openings and complicated the geometry as he fit together its rusticated blocks.

The northwest structure is more assertively English, but high parapet walls, hiding much of the roof, and rich rubbed-and-gauged brickwork draw on the blocky appearance of Rosewell and its classical details. The scale of the chimneys is inspired by the large square smokestacks at the Nelson House in neighboring Yorktown, and at Shirley, to the west in Charles City County. Terry has written about his admiration for old buildings whose designers were long ago forgotten, for good design crafted by now-anonymous people. The northwest walls, with brick cornices and Ionic niche, grows directly from such structures.

The richness of this tradesmen's classicism contrasts with the severity of the northeast elevations' yellowish brick walls and deep post-Revolutionary eaves. The principal decoration on the otherwise chaste brick box is a crisp wooden shop front. Its general conception is that of a thousand shops, from East London to Philadelphia. The details have high pedigree, however, drawn from James Stuart and Nicholas Revett's 1787 architectural drawings of the Erechtheion, the complex Athenian temple near the Parthenon.

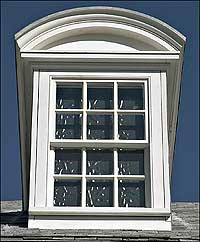

A wooden fourth front looks borrowed from a Virginia crossroads, except for its decidedly English round-headed dormer window. Terry sees humor in such combinations, but he is more interested in providing the public with instructive details than in esoteric wit. "Nothing good is entirely new," he says, hoping that what he has learned from the old buildings of anonymous architects and used here will be adopted by builders more interested in pleasing effect than in cultivating the designer's fame.

Web Exclusives

For further reading:

Listen to a Behind the Scenes Interview: Architectural Research. Ed Chappell discusses the value of preserving and restoring buildings in understanding how people lived their lives in the past.